An Empirical Study on Emergency of Distant Tertiary Education in the Southern Region of Bangladesh during COVID-19: Policy Implication

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

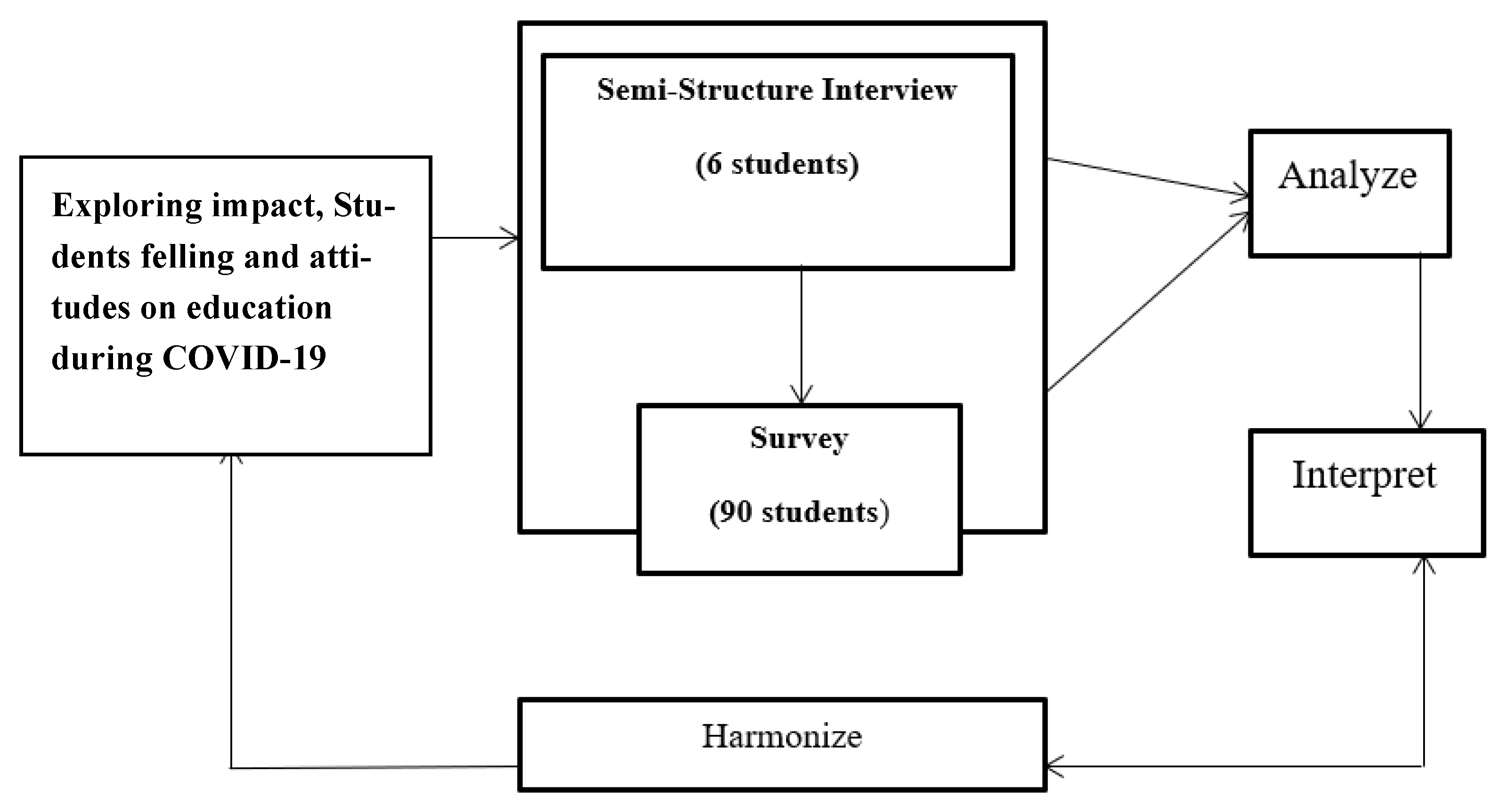

3. Methodology

3.1. Quantitative Research

3.1.1. Sample Size

3.1.2. Instrument

3.1.3. Data Collection Procedure

3.1.4. Data Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Research

3.3. Ethical Considerations

4. Data Analysis and Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crawford, J.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Sustainability in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Mortelmans, L.J.; Robinson, Y.; Burkle, F.M.; Goniewicz, K. Civilian-Military Collaboration before and during COVID-19 Pandemic—A Systematic Review and a Pilot Survey among Practitioners. Sustainability 2022, 14, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A. Students’ Perceptions of the Actual Use of Mobile Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic in Higher Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, F.; dos Santos, G.; Martinho, C. Strengths and Weaknesses of Emergency Remote Teaching in Higher Education from the Students’ Perspective: The Portuguese Case. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 871036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayittey, F.K.; Dhar, B.K.; Anani, G.; Chiwero, N.B. Gendered burdens and impacts of SARS-CoV-2: A review. Health Care Women Int. 2020, 41, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.A.; Barros, A.; Simão, A.M.V.; Pereira, D.; Flores, P.; Fernandes, E.; Costa, L.; Ferreira, C. Portuguese higher education students’ adaptation to online teaching and learning in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Personal and contextual factors. High. Educ. 2021, 83, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubicz-Nawrocka, T.; Bovill, C. Do students experience transformation through co-creating curriculum in higher education? Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Masud, A.; Alamgir Hossain, M.; Kumer Roy, D.; Shakhawat Hossain, M.; Nurun Nabi, M.; Ferdous, A.; Tebrak Hossain, M. Global Pandemic Situation, Responses and Measures in Bangladesh: New Normal and Sustainability Perspective. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Bashir, A.; Basu, B.L.; Uddin, M.E. Emergency online instruction at higher education in Bangladesh during COVID-19: Challenges and suggestions. J. Asia TEFL 2020, 17, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayittey, F.K.; Chiwero, N.B.; Dhar, B.K.; Tettey, E.L.; Saptoro, A. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: A narrative review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e15012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A. Online teaching experiences in higher education institutions of Afghanistan during the COVID-19 outbreak: Challenges and opportunities. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2021, 8, 1947008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A. Effects of COVID-19 on the academic performance of Afghan students’ and their level of satisfaction with online teaching. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2021, 8, 1933684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emon, E.K.H.; Alif, A.R.; Islam, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the institutional education system and its associated students in Bangladesh. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2020, 11, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Sunna, T.C.; Sanjoy, S. Response to COVID-19 in Bangladesh: Strategies to resist the growing trend of COVID-19 in a less restricted situation. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 32, 471–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, B.K.; Ayittey, F.K.; Sarkar, S.M. Impact of COVID-19 on Psychology among the University Students. Glob. Chall. 2020, 4, 2000038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi Md, A.I.; Al Masud, A.; Shuvro, R.A.; Hossain, A.I.; Rahman, M.K. Bangladesh and SAARC Countries: Bilateral Trade and Flaring of Economic Cooperation. Etikonomi 2022, 21, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi Md, A.I.; Nahiduzzaman Md Harymawan, I.; Masud, A.A.; Dhar, B.K. Impact of COVID-19 on Financial Performance and Profitability of Banking Sector in Special Reference to Private Commercial Banks: Empirical Evidence from Bangladesh. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and Beyond; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.un.org/development (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Dutta, S.; Smita, M.K. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on tertiary education in Bangladesh: Students’ perspectives. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.P.; Meng, S.; Wu, Y.J.; Mao, Y.P.; Ye, R.X.; Wang, Q.Z.; Sun, C.; Sylvia, S.; Rozelle, S.; Raat, H.; et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huque, S.M.R.; Aziza, T.; Farzana, T.; Islam, M.N. Strategies to Mitigate the COVID-19 Challenges of Universities in Bangladesh. In Handbook of Research on Strategies and Interventions to Mitigate COVID-19 Impact on SMEs; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 563–587. [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.Y. Student’s Attitude and Satisfaction towards Transformative Learning: A Research Study on Emergency Remote Learning in Tertiary Education. Creat. Educ. 2021, 12, 494–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majed, N.; Jamal, G.R.A.; Kabir, M.R. Online Education: Bangladesh Perspective, Challenges and Way Forward | The Daily Star. 28 July 2020. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/online/news/online-education-bangladesh-perspective-challenges-and-way-forward-1937625 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Neuwirth, L.S.; Jović, S.; Mukherji, B.R. Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2020, 27, 147797142094773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, N.U. Prospects and Perils of Online Education in Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.newagebd.net/article (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Nabi Md, N.; Akter Mst, M.; Habib, A.; Al Masud, A.; Kumer Pal, S. Influence of CSR stakeholders on the textile firms performances. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, S.; Muluye, W. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system in developing countries: A review. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, E.K.; Dhar, B.K.; Stasi, A. Volatility of the US stock market and business strategy during COVID-19. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2022, 5, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanum, F.; Alam, M.M. Tertiary Level Learners’ Perceptions of Learning English through Online Class during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Quantitative Approach. A Res. J. Engl. Stud. 2021, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jili, N.N.; Ede, C.I.; Masuku, M.M. Emergency Remote Teaching in Higher Education During COVID-19: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. High. Educ. 2021, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social and educational aspects of Saudi university students’ lives. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R.A. literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L.; Gupta, T.; Shree, A. Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.N.; Al-Mannai, R.; Agouni, A. An Emergency Switch to Distance Learning in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experience from an Internationally Accredited Undergraduate Pharmacy Program at Qatar University. Med. Sci. Educ. 2020, 30, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukuka, A.; Shumba, O.; Mulenga, H.M. Students’ experiences with remote learning during the COVID-19 school closure: Implications for mathematics education. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Sharma, R.C. Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to corona virus pandemic. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhov, I.; Opolska, N.; Bogus, M.; Anishchenko, V.; Biryukova, Y. Emergency Distance Education in the Conditions of COVID-19 Pandemic: Experience of Ukrainian Universities. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvekar, H. Educational concerns of children with disabilities during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Ince, E.; Kabul, A.; Diler, I. Distance education in higher education in the COVID-19 pandemic process: A case of Isparta Applied Sciences University. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. Sci. 2020, 4, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lily, A.E.; Ismail, A.F.; Abunasser, F.M.; Alqahtani, R.H.A. Distance education as a response to pandemics: Coronavirus and Arab culture. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, T. Learning in the COVID-19 Era: Higher Education Students and Faculty’s Experience with Emergency Distance Education. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn 2021, 16, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M.; Eteokleous, N.; Stylianou-Georgiou, A. Emergency Remote Learning in Higher Education in Cyprus during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Zoom-Out View of Challenges and Opportunities for Quality Online Learning. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Rice, M.F. Instructional designers’ roles in emergency remote teaching during Covid-19. Distance Educ. 2021, 42, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.; Ringer, A.; Saville, K.; Parris, M.A.; Kashi, K. Students’ motivation and engagement in higher education: The importance of attitude to online learning. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O. The current state and impact of COVID-19 on digital higher education in Germany. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H.; Park, S. Building a structural model of motivational regulation and learning engagement for undergraduate and graduate students in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misirli, O.; Ergulec, F. Emergency remote teaching during the COVID 19 pandemic: Parents experiences and perspectives. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6699–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon-Calvin, S. COVID-19 pandemic: An era of opportunities and challenges in higher education. J. Educ. Technol. Health Sci. 2021, 7, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramij, G.o.l.a.m.; Sultana, A. Preparedness of Online Classes in Developing Countries amid COVID-19 Outbreak: A Perspective from Bangladesh. SSRN Electron. J. 2020, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Roy, S.K.; Roy, F. Student’s perception of mobile learning during COVID-19 in Bangladesh: University Student Perspective. Aquademia 2020, 4, ep20023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allo, M.D.G. Is the online learning good in the midst of Covid-19 Pandemic? The case of EFL learners. J. Sinestesia 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Batez, M. ICT Skills of University Students from the Faculty of Sport and Physical Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Yadav, S.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on higher education and research. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 2020, 14, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, A.Q.; Orfan, S.N.; Nawi, A.M. Students’ Perception of Lecturers’ Behaviors in the Learning Environment. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2021, 9, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, A.Q.; Said, H.; Nor, F.M.; Abd Ghani, F. The relationship between university lecturers’ behaviour and students’ motivation. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Dron, J. Three Generations of Distance Education Pedagogy. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2011, 12, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simonson, M.; Smaldino, S.; Albright, M.; Zvacek, S. Teaching and Learning at a Distance, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, B. The Feasibility of a Theory of Teaching for Distance Education and a Proposed Theory; ZIFF Papiere 60; FernUniversitat: Hagen, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D.R.; Archer, W. A theory of community of inquiry. In Handbook of Distance Education; Moore, M.G., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, D. Foundations of Distance Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pyari, D. Theory and Distance Education: At a Glance; IPCSIT (12); IACSIT Press: Singapore, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vuong, Q.H. Reform retractions to make them more transparent. Nature 2020, 582, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.G. The theory of transactional distance. In Handbook of Distance Education; Moore, M.G., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Ching, Y.H.; Mathews, J.; Carr-Chellman, A. Undergraduate students’ self-regulated learning experience in web-based learning environments. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 2009, 10, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Haythornthwaite, C. Facilitating collaboration in online learning. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2006, 10, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J. Situating learning in communities of practice. Perspect. Soc. Shar. Cogn. 1991, 2, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, K.; Shen, J.; Hiltz, S.R. Assessment and collaboration in online learning. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2006, 10, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almanthari, A.; Maulina, S.; Bruce, S. Secondary School Mathematics Teachers’ Views on E-Learning Implementation Barriers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Indonesia. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2020, 16, em1860. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, A.C.; Creswell, J.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Smith, K.C.; Meissner, H.I. Best practices in mixed methods for quality of life research. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bączek, M.; Zagańczyk-Bączek, M.; Szpringer, M.; Jaroszyński, A.; Wożakowska-Kapłon, B. Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study of Polish medical students. Medicine 2021, 100, e24821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Das Gupta, A.; Hasan, M.D.; Kabir, K.R. Current Status about Covid-19 Impacts on Online Education System: A Review in Bangladesh. Kazi Rafia, Current Status about COVID-19 Impacts on Online Education System: A Review in Bangladesh. Sylhet Uni. J. 2021, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbat, F.F.; Abu Daabes, A.S. E-proctored exams during the COVID-19 pandemic: A close understanding. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6589–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu-Fordjour, C.; Koomson, C.K.; Hanson, D. The impact of COVID-19 on learning-the perspective of the Ghanaian student. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2020, 7, 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Gray, D. (Eds.) Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, R. Theoretical. Challenges for Distance Education in the 21st Century: A Shift from Structural to Transactional Issues. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2000, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, J.; Arnhold, N.; Bassett, R.M. The Big Bad Wolf Moves South: How COVID-19 Affects Higher Education Financing in Developing Countries; World Bank Blogs: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.; Islam, K.M.Z.; Al Masud, A.; Biswas, S.; Hossain, A. Behavioral intention and continued adoption of Facebook: An exploratory study of graduate students in Bangladesh during the Covid-19 pandemic. Management 2021, 25, 153–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyema, E.M.; Eucheria, N.C.; Obafemi, F.A.; Sen, S.; Atonye, F.G.; Sharma, A.; Alsayed, A.O. Impact of Coronavirus pandemic on education. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 11, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, K.A.; Shah, S.S.; Richardson, T.; Hartley, D.; Hall, M.; Warniment, A.; Timmons, K.; Bosse, D.; Ferris, S.A.; Brady, W.; et al. Association between statewide school closure and COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the US. JAMA 2020, 324, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.Y.; Dahmash, E.Z.; Al-Rousan, R.; Alwafi, H.; Alrawashdeh, H.M.; Ghoul, I.; Abidine, A.; Bokhary, M.A.; AL-Hadithi, H.T.; Ali, D.; et al. Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agung, A.S.N.; Surtikanti, M.W.; Quinones, C.A. Students’ perception of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study on the English students of STKIP Pamane Talino. SOSHUM J. Sos. Dan Hum. 2020, 10, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, I.A. Bangladeshi Children Share Experiences of Remote Learning and the Challenges They Face; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fatema, K. “Weak Infrastructure Denies Benefit of Online Classes to Many” and 27 August. 2020. Available online: https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/education/online-class-where-education-has-turned-misery-125077 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Islam, S. Online Education and Reality in Bangladesh. 10 May. 2020. Available online: https://www.observerbd.com/news.php?id=256102 (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Mustafa, N. Impact of the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic on education. Int. J. Health Prefer. Res. 2020, 4, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Khlaif, Z.N.; Salha, S.; Affouneh, S.; Rashed, H.; El Kimishy, L.A. The Covid-19 epidemic: Teachers’ responses to school closure in developing countries. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2021, 30, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Haque, S.; Dawadi, S.; Giri, R.A. Preparations for and practices of online education during the Covid-19 pandemic: A study of Bangladesh and Nepal. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. Private Universities Can Run Academic Activities Online: UGC. Prothom Alo” 30 April. 2020. Available online: https://en.prothomalo.com/youth/private-universities-can-run-academic-activities-online-ugc (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Aldulaimi, S.H. E-Learning in Higher Education and Covid-19 Outbreak: Challenges and Opportunities. Psychol. Educ. J. 2021, 58, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Potenza, M.N. Panic and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi people: An online pilot survey early in the outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalis, T. Planning and evaluation during educational disruption: Lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic for treatment of emergencies in education. Eur. J. Educ. Studies 2020, 7, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gazi, M.A.I.; Alam, M.A. Leadership; Efficacy, Innovations and their Impacts on Productivity. ASA Univ. Rev. 2014, 8, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 43 | 47% |

| Female | 47 | 52% | |

| Total | 90 | 100% | |

| Age | 21 to 25 | 65 | 71.1% |

| 26 to 30 | 25 | 28.9% | |

| Total | 90 | 100% | |

| Level of education | Undergraduate | 45 | 50% |

| Graduate | 45 | 50% | |

| 90 | 100% | ||

| Teaching | Statement | Items | References |

| Despite the COVID 19 outbreak, my teachers continued to teach as usual. | T1 | [5,12,13,31,56] | |

| I had contact with my teachers through a web-based platform. | T2 | ||

| I receive constructive feedback from my lectures. | T3 | ||

| I receive support from my lecturers. | T4 | ||

| Online classes were very effective for me. | T5 | ||

| Learning | I approached web-based classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. | L1 | [12,13,31,71] |

| I was connected to the Internet during the COVID-19 pandemic. | L2 | ||

| I had a tech installation during the COVID-19 pandemic. | L3 | ||

| I am using various resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. | L4 | ||

| I was better acquainted with the use of technology. | L4 | ||

| Learners’ performance | The COVID-19 pandemic impacted my learning performance. | LP1 | [1,5,12,13] |

| My subject expertise was influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. | LP2 | ||

| The COVID-19 pandemic affected the nature of my learning. | LP3 | ||

| Students’ objectives | The COVID-19 outbreak has altered my plans for the future. | SO1 | [12,13,31,56] |

| The COVID-19 pandemic delayed my graduation. | SO2 | ||

| My educational activities were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic | SO3 | ||

| Student’s feelings | Because of COVID-19, I believe I didn’t read up for quite a long time. | SF1 | [1,56,72] |

| The COVID-19 pandemic impacted me psychologically. | SF2 | ||

| I believe I lost instructive open doors during the COVID-19. | SF3 |

| Category | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching | 5 | 0.881 |

| Learning | 5 | 0.862 |

| Students’ Achievements | 3 | 0.791 |

| Students’ Goals | 3 | 0.775 |

| Students’ Feelings | 3 | 0.758 |

| Overall | 19 | 0.894 |

| Variable | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 43 | 2.55 | 0.296 | 0.13 |

| Female | 47 | 2.53 | 0.215 | ||

| Age | 21–25 | 65 | 2.535 | 0.304 | 0.002 |

| 26–30 | 25 | 2.606 | 0.353 | ||

| Education Level | Undergraduate | 45 | 2.597 | 0.212 | 0.048 |

| Graduate | 45 | 2.566 | 0.259 | ||

| Statement | SD | D | A | SA | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 5.6% | 12.2% | 75.6% | 3.3% | 2.82 |

| T2 | 0 | 6.7% | 71.1% | 15.6% | 2.91 |

| T3 | 0 | 20% | 74.4% | 2.2% | 2.65 |

| T4 | 0 | 13.3% | 78.9% | 4.6% | 3.11 |

| T5 | 3.3% | 38.9% | 41.1% | 13.3% | 2.81 |

| Statement | SD | D | A | SA | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 0 | 5.6% | 77.8% | 16.7% | 3.11 |

| L2 | 3.3% | 22.2% | 64.4% | 10% | 2.81 |

| L3 | 0 | 16.7% | 77.8% | 5.6% | 2.89 |

| L4 | 0 | 18.9% | 67.8% | 11.1% | 2.92 |

| L5 | 3.3% | 38.9% | 41.1% | 13.3% | 2.653 |

| Statement | SD | D | A | SA | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LP1 | 0% | 2.2% | 64.4% | 33.3% | 3.29 |

| LP2 | 0% | 2.2% | 73.3% | 24.4 | 3.20 |

| LP3 | 0% | 3.3% | 65.6% | 31.1% | 3.24 |

| Statement | SD | D | A | SA | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO1 | 13.3% | 0% | 52.2% | 34.4% | 3.07 |

| SO2 | 0% | 0% | 33.3% | 6.7% | 3.65 |

| SO3 | 0% | 2.2% | 47.8% | 50.% | 3.48 |

| Statement | SD | D | A | SA | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF1 | 0% | 10.% | 54.4% | 35.6% | 3.48 |

| SF2 | 2.2% | 5.6% | 62.2% | 30% | 3.25 |

| SF3 | 0% | 16.7% | 41.1% | 40.1% | 3.20 |

| Variables. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COVID-19 Pandemic | 1 | |||||

| 2. Teaching | 0.438 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Learning | 0.291 ** | 0.0361 * | 1 | |||

| 4. Students’ Achievements | 0.126 * | 0.118 ** | 0.116 | 1 | ||

| 5. Students’ Goals | −0.328 ** | 0.127 | 0.314 * | 0.138 | 1 | |

| 6. Students’ Feelings | 0.221 | −0.241 | 0.0.112 | 0.123 | −0.231 | 1 |

| Model | Sum of Square | df | Mean | F | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 1.883 | 2 | 0.941 | 1.605 | 0.005 |

| Residual | 51.017 | 87 | 0.586 | ||

| Total | 52.900 | 89 |

| “Themes” | “Participant 1” | “Participant 2” | “Participant 3” | “Participant 4” | “Participant 5” | “Participant 6” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ experiences of teaching during COVID-19 | “Our professors established chat groups in which they shared stuff.” | “I lived in a part of town and couldn’t attend my classes most of the time.” | “Since numerous Understudies didn’t have a cell phone or a PC, online talks were incapable for them.” | “Our professors used to contact us via ZOOM and would send us recordings of their lectures.” | “I wasn’t happy with the teaching because we hadn’t had any lectures in months.” | “Lecturers used to use social media to communicate and share some lesson resources.” |

| Students’ experiences of learning during COVID-19 | “Since most of the understudies didn’t approach the Internet, the web-based addresses ceased after a couple of meetings.” | “Web-based learning was incapable for me because of an absence of Internet access and innovative issues.” | “I used to make phone calls to my classmates and ask them for the tasks that the lecturers had assigned.” | “Because our instructors were not serious about their teaching, the learning experience was not favorable.” | “Coronavirus hurt my learning style and fixation when it came to learning new things. I teamed up with a colleague on a class project.” | “I used to rehash my sections and notes; however, my learning result was poor because the educator put no squeeze on us to concentrate sufficiently on” |

| Challenge | “Sometimes I didn’t have power, and most of the time I had Internet issues.” | “I had difficulty with the Internet and electricity.” | “I had financial difficulties and was unable to get a smartphone in 2020, and as a result of which I was unable to study efficiently.” | “We had extremely slow Internet and were unable to download the shared information.” | “Our university was closed, and we were unable to attend classes. Have months of class.” | “Have no class this month.” |

| Solutions | “The Ministry of Higher Education ought to foster a fantastic learning programming” | “The Ministry ought to present a product which will be wide open and work with slow Internet because In the locale, we have 2G Internet as it were.” | “The Ministry ought to lay out a strategy for monetarily burdened understudies.” | “Teaching and learning should never be interrupted, and the Ministry can design a practical and effective learning application.” | “In emergencies, such as the COVID-19, instructors and lecturers should encourage students and check their learning progress.” | “The Ministry of Higher Education ought to plan and execute a web-based stage that is available to all understudies and for nothing.” |

| The Impact of COVID-19 on students’ learning. | “Coronavirus made both positive and adverse consequences, albeit the last option unfavorably affected my learning.” | “As a result of the horrendous Internet, I had the most exceedingly terrible opportunity for growth in my life, I was unable to try and peruse messages on courier and What’s app.” | “I was under a lot of stress and felt like I hadn’t studied in years.” | “Due to my less than stellar scores because of COVID-19, my graduation was delayed, and I was worried about my well-being and future.” | “The good consequence is that we had our first encounter with online learning, which introduced us to online learning.” | “Coronavirus delayed my graduation, I lost my employment as an educator in an instructive focus, and I was focused on during COVID-19.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gazi, M.A.I.; Masud, A.A.; Sobhani, F.A.; Dhar, B.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Hossain, A.I. An Empirical Study on Emergency of Distant Tertiary Education in the Southern Region of Bangladesh during COVID-19: Policy Implication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054372

Gazi MAI, Masud AA, Sobhani FA, Dhar BK, Hossain MS, Hossain AI. An Empirical Study on Emergency of Distant Tertiary Education in the Southern Region of Bangladesh during COVID-19: Policy Implication. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054372

Chicago/Turabian StyleGazi, Md. Abu Issa, Abdullah Al Masud, Farid Ahammad Sobhani, Bablu Kumar Dhar, Mohammad Sabbir Hossain, and Abu Ishaque Hossain. 2023. "An Empirical Study on Emergency of Distant Tertiary Education in the Southern Region of Bangladesh during COVID-19: Policy Implication" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054372