Exploring the Effect of Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from Korean Firefighters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Emotional Labor and Turnover Intention

3. The Moderating Role of POS

4. Model Specification

4.1. Data Sources and Sample

4.2. Dependent Variables

4.3. Explanatory Variables

4.3.1. Surface and Deep Acting

4.3.2. POS

4.4. Controls

4.5. Measurement Reliability and Validity

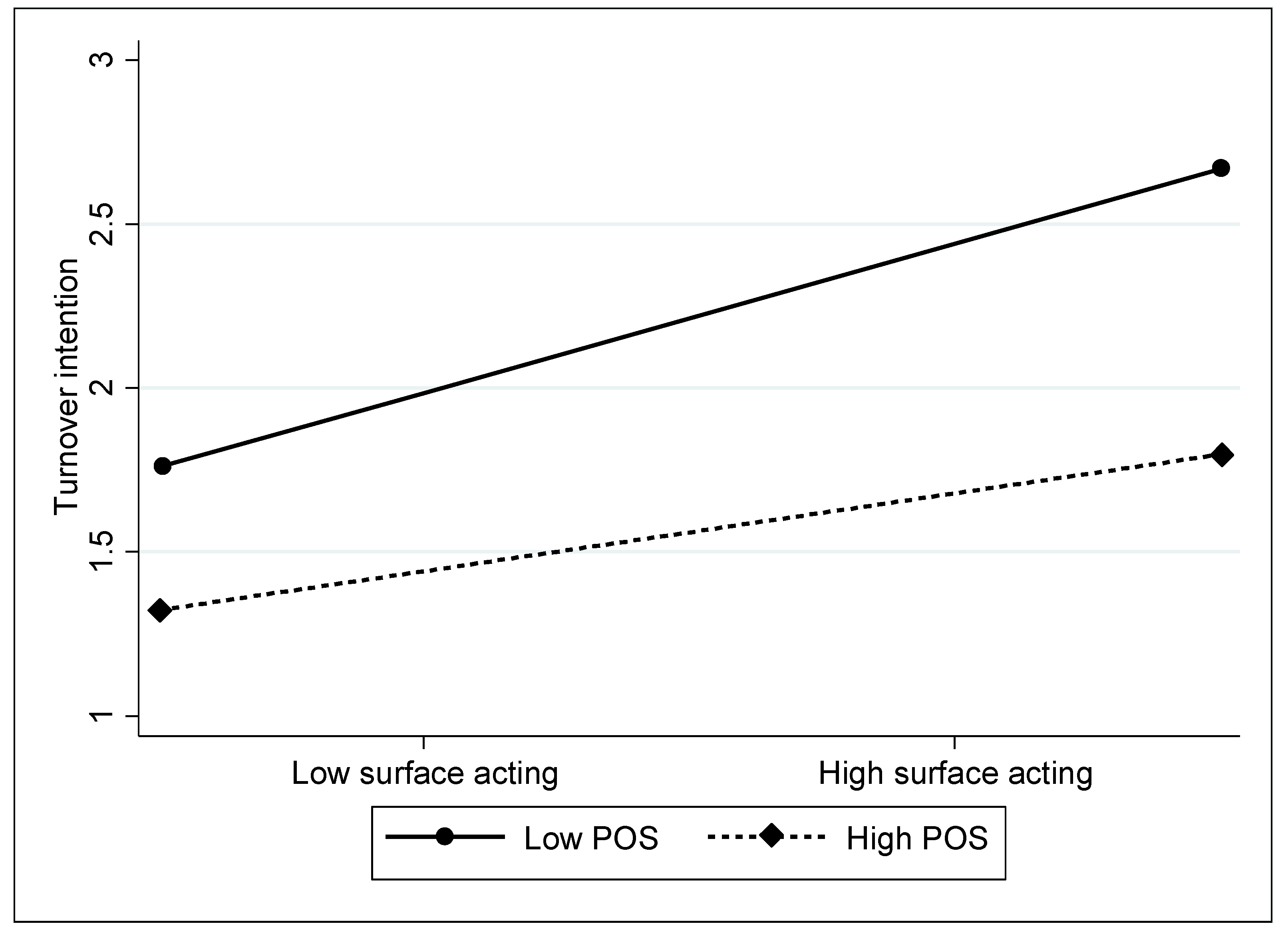

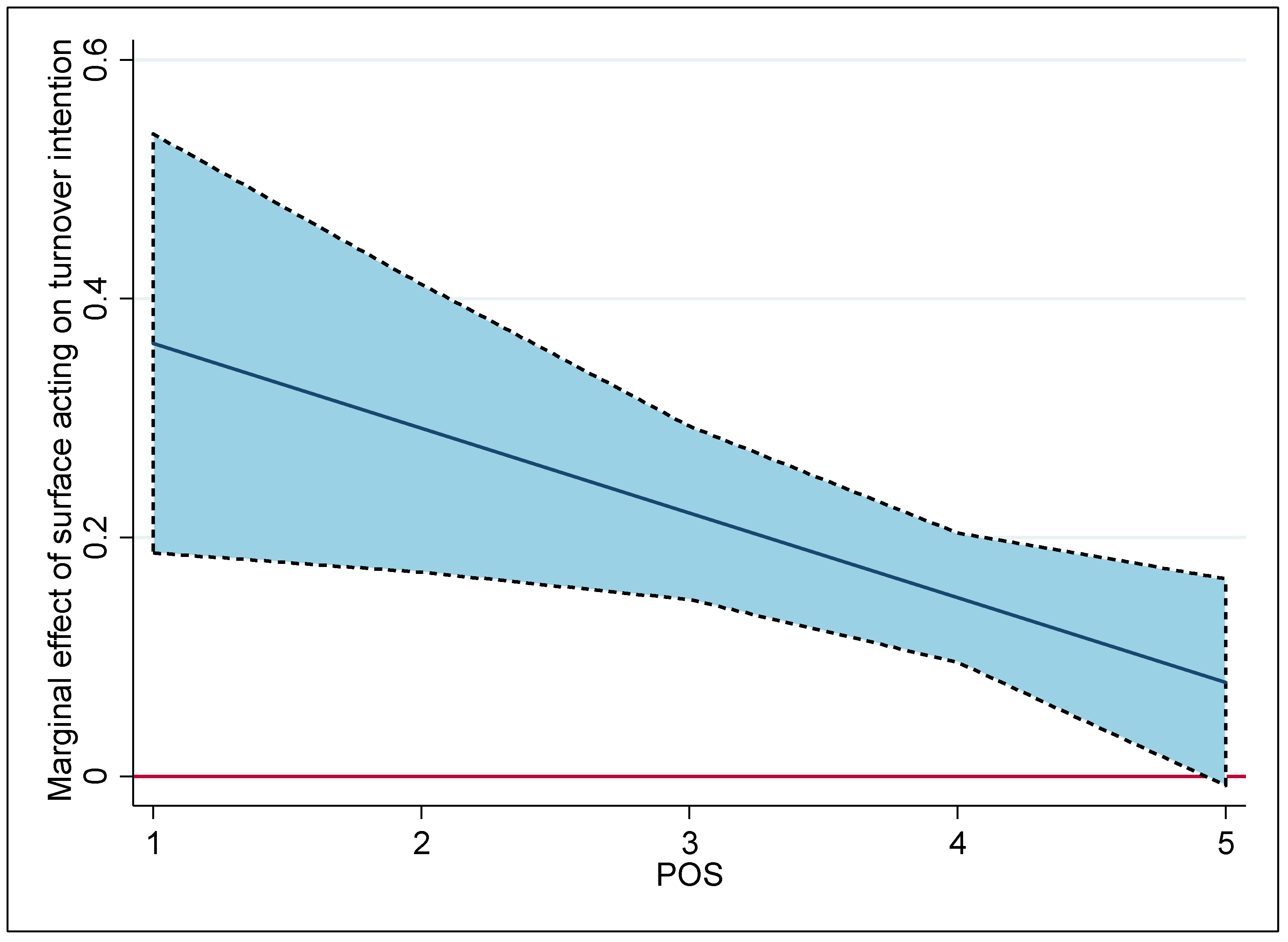

5. Results

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion of Results

6.2. Practical Implicationss

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boffa, J.W.; Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Norr, A.M.; Joiner, T.E.; Schmidt, N.B. PTSD symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among firefighters. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 84, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chan, S.C.; Lam, W.; Nan, X. The joint effect of leader–member exchange and emotional intelligence on burnout and work performance in call centers in China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, D.J.; Gallagher, M.W.; Bartlett, B.A.; Tran, J.; Vujanovic, A.A. The unique and interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and emotion dysregulation in relation to posttraumatic stress, depressive, and anxiety symptoms among trauma-exposed firefighters. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.G.; Kim, K.-S.; Ryoo, J.-H.; Yoo, S.-W. Relationship between occupational stress and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Korean male firefighters. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, D.-Y.; Chang, S.-J. Moderating effects of organizational climate on the relationship between emotional labor and burnout among Korean firefighters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J. From emotional labor to customer loyalty in hospitality: A three-level investigation with the JD-R model and COR theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3742–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ziwei, Y. The impact of surface and deep acting on employee creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2020, 32, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.-Y.; Hyun, D.-S.; Jeung, D.-Y.; Kim, C.-S.; Chang, S.-J. Organizational climate effects on the relationship between emotional labor and turnover intention in Korean firefighters. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, T.; Guenter, H.; van Emmerik, H. Team turnover and task conflict: A longitudinal study on the moderating effects of collective experience. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1287–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakova, M.; Mcdowall, A.; Bianvet, C. Are organisational politics responsible for turnover intention in French Firefighters? Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 72, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.-S. Moderated mediation effect of mindfulness on the relationship between muscular skeletal disease, job stress, and turnover among Korean firefighters. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, W.-M.; Han, S.-J.; Yoo, J.-J.; Moon, T.W. The moderating role of perceived organizational support on the relationship between emotional labor and job-related outcomes. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. Emotional labor, teacher burnout, and turnover intention in high-school physical education teaching. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Lee, T.W.; Griffeth, R.W. Reviewing employee turnover: Focusing on proximal withdrawal states and an expanded criterion. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Jun, J.-K. Is all support equal? The moderating effects of supervisor, coworker, and organizational support on the link between emotional labor and job performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2017, 20, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Grandey, A.A. Emotional Labor and Burnout: Comparing Two Perspectives of “People Work”. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.E.; Groth, M.; Frenkel, S.J. Relationships between emotional labor, job performance, and turnover. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Gabriel, A.S. Emotional labor at a crossroads: Where do we go from here? Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Song, H.J. Determinants of turnover intention of social workers: Effects of emotional labor and organizational trust. Public Pers. Manag. 2017, 46, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Jeon, J.-E. Daily emotional labor, negative affect state, and emotional exhaustion: Cross-level moderators of affective commitment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.J.; Cropanzano, R.; Van Wagoner, P.; Keplinger, K. Emotional Labor Within Teams: Outcomes of Individual and Peer Emotional Labor on Perceived Team Support, Extra-Role Behaviors, and Turnover Intentions. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 38–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.-W.; Wang, I.-A. The relationship between newcomers’ emotional labor and service performance: The moderating roles of service training and mentoring functions. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2729–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Z. How Does Emotional Labor Influence Voice Behavior? The Roles of Work Engagement and Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Huang, S.; Hou, P. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, perceived organizational support, and job satisfaction: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musenze, I.A.; Mayende, T.S. Ethical leadership (EL) and innovative work behavior (IWB) in public universities: Examining the moderating role of perceived organizational support (POS). Manag. Res. Rev. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubaca, U.; Majid Khan, M. The impact of perceived organizational support and job resourcefulness on supervisor-rated contextual performance of firefighters: Mediating role of job satisfaction. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2021, 29, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.-R.; Cho, I.; Choi, Y.; Cho, S.-I. Effects of emotional labor factors and working environment on the risk of depression in pink-collar workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, D.-Y.; Kim, C.; Chang, S.-J. Emotional labor and burnout: A review of the literature. Yonsei Med. J. 2018, 59, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hothschild, A.R. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Li, H. Psychological capital, emotional labor and exhaustion: Examining mediating and moderating models. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvey, R.W.; Renz, G.L.; Watson, T.W. Emotionality and job performance: Implications for personnel selection. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Ferris, G.R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 16, pp. 103–147. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.I.; Oh, S.; Kim, J.-H. The impact of emotional labor on the severity of PTSD symptoms in firefighters. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 83, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.A.; Barnes, C.M. A multilevel field investigation of emotional labor, affect, work withdrawal, and gender. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imose, R.A.; Finkelstein, L.M. A multilevel theoretical framework integrating diversity and emotional labor. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 718–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, B.R.; Konijn, E.A.; Bakker, A.B. Emotional labor among police officers: A diary study relating strain, emotional labor, and service performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 852–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaeli, A.; Sutton, R.I. Expression of Emotion as Part of the Work Role. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B.; Olekalns, M.; Rees, L. An Ethical Analysis of Emotional Labor. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C.M. Understanding hotel employees’ service sabotage: Emotional labor perspective based on conservation of resources theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Schewe, A.F. On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandey, A.A.; Fisk, G.M.; Steiner, D.D. Must “Service with a Smile” Be Stressful? The Moderating Role of Personal Control for American and French Employees. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, L.S.; Grandey, A.A. Display rules versus display autonomy: Emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and task performance in a call center simulation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Martinez, L.R.; Lv, Q. Explaining the Link Between Emotional Labor and Turnover Intentions: The Role of In-Depth Communication. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2017, 18, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Hom, P.W.; Griffeth, R.W. The effects of proximal withdrawal states on job attitudes, job searching, intent to leave, and employee turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1436–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, J.B.; Johnson, J.T. The Effects of Perceived Supervisor Support, Perceived Organizational Support, and Organizational Justice on Turnover among Salespeople. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2009, 29, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, M.; Moreira, A.; Pitacho, L. Perceived organizational culture and turnover intentions: The serial mediating effect of perceived organizational support and job insecurity. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawley, D.; Houghton, J.D.; Bucklew, N.S. Full article: Perceived Organizational Support and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Effects of Personal Sacrifice and Job Fit. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 150, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryer, C.; Jordan, C.; Firns, I.; Travaglione, A. Predicting turnover intentions: The interactive effects of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, C. Reducing turnover intention: Perceived organizational support for frontline employees. Front. Bus. Res. China 2020, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanyu, G.; Jizu, L. The effect of emotional intelligence on unsafe behavior of miners: The role of emotional labor strategies and perceived organizational support. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.C.; Edwards, B.D.; Arnold, T.; Frazier, M.L.; Finch, D.M. Work stressors, role-based performance, and the moderating influence of organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Dollard, M.F.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, P.J. When do job demands particularly predict burnout? The moderating role of job resources. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 766–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjak, A.; Černe, M.; Nagy, N.; Bruch, H. Job demands and burnout: The multilevel boundary conditions of collective trust and competitive pressure. Hum. Relat. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giao, H.N.K.; Vuong, B.N.; Huan, D.D.; Tushar, H.; Quan, T.N. The effect of emotional intelligence on turnover intention and the moderating role of perceived organizational support: Evidence from the banking industry of Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Sun, R. How does council–manager conflict affect managerial turnover intention? The role of job embeddedness and cooperative context. Public Adm. 2020, 98, 974–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Croyle, M.H.; Gosserand, R.H. The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kao, D. A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among US child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 47, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wróbel, M. Can empathy lead to emotional exhaustion in teachers? The mediating role of emotional labor. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2013, 26, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccucci, N.M.; Saldivar, K. The Status of Employment Discrimination Suits in Police and Fire Departments Across the United States. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2014, 34, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G. Korean Emotional Laborers’ Job Stressors and Relievers: Focus on Work Conditions and Emotional Labor Properties. Saf. Health Work 2015, 6, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, A.B.; Goodman, J.M.; Treadway, D.C.; Breland, J.W. Perceived Organizational Support as a Moderator of Emotional Labor/Outcomes Relationships. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, S.L.; Dahling, J.J.; Levy, P.E.; Diefendorff, J.M. A predictive study of emotional labor and turnover. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsen, M.; Ozmen, D. The relationship between emotional labour and job satisfaction in nursing. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2020, 67, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F. Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 8, 304. ISBN 978-1-4338-0933-0. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J.L.; Hondeghem, A. Building theory and empirical evidence about public service motivation. Int. Public Manag. J. 2008, 11, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potipiroon, W.; Srisuthisa-ard, A.; Faerman, S. Public service motivation and customer service behaviour: Testing the mediating role of emotional labour and the moderating role of gender. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 650–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-W.; Yang, K.; Fu, K.-J. Motivational bases and emotional labor: Assessing the impact of public service motivation. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. A job demands-resources approach to public service motivation. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Woolf, E.F.; Hurst, C. Is Emotional Labor More Difficult for Some Than for Others? A Multilevel, Experience-Sampling Study. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.; Chen, Z. When I put on my service mask: Determinants and outcomes of emotional labor among hotel service providers according to affective event theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, A.; Schott, C.; Nitzl, C.; Alfes, K. Public service motivation and prosocial motivation: Two sides of the same coin? Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 974–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Rhee, S.-Y.; Ahn, K.-H. Positive psychological capital and emotional labor in Korea: The job demands-resources approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.Y.; Park, H. The effect of nurse’s emotional labor on turnover intention: Mediation effect of burnout and moderated mediation effect of authentic leadership. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2019, 49, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-K.; Kim, I.-H. The effects of job characteristics, personal-organizational fit and emotional labor on turnover intention of nurses in geriatric hospitals. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 396.28 *** | 84 | 4.72 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.03 |

| Three-factor model | 3249.48 *** | 87 | 37.35 | 0.15 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.12 |

| (SA and DA combined) | |||||||

| Two-factor model | 5235.86 *** | 89 | 58.83 | 0.19 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.16 |

| (SA, DA, and POS combined) | |||||||

| One-factor model | 8079.25 *** | 90 | 89.77 | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.17 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Turnover intention | 1 | |||||||||

| 2 | Surface acting | 0.29 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3 | Deep acting | 0.06 | 0.17 | 1 | |||||||

| 4 | POS | −0.43 | −0.31 | 0.04 a | 1 | ||||||

| 5 | Gender (Female = 1) | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.11 | 1 | |||||

| 6 | Age | −0.02 a | −0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | −0.15 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | Rank | −0.03 a | −0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.81 | 1 | |||

| 8 | Education | 0.05 | 0.004 a | −0.01 a | −0.08 | 0.13 | −0.05 | −0.08 | 1 | ||

| 9 | Tenure | −0.04 a | −0.12 | 0.15 | 0.15 | −0.11 | 0.85 | 0.90 | −0.13 | 1 | |

| 10 | Marital status (Married=1) | 0.00 a | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 1 |

| Mean | 2.41 | 2.47 | 2.84 | 3.67 | 0.14 | 2.34 | 2.63 | 2.31 | 2.58 | 0.62 | |

| SD | 1.05 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.34 | 0.97 | 1.40 | 0.83 | 1.76 | 0.49 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (S.E.) | (S.E.) | (S.E.) | ||||

| Gender (Female = 1) | 0.116 | ** | 0.139 | ** | 0.141 | ** |

| (0.052) | (0.068) | (0.068) | ||||

| Age | 0.030 | 0.057 | 0.058 | |||

| (0.036) | (0.048) | (0.048) | ||||

| Job grade | −0.001 | 0.014 | 0.013 | |||

| (0.026) | (0.039) | (0.039) | ||||

| Education | 0.020 | 0.015 | 0.014 | |||

| (0.023) | (0.030) | (0.030) | ||||

| Tenure | 0.003 | −0.018 | −0.019 | |||

| (0.040) | (0.036) | (0.036) | ||||

| Marital status (Married = 1) | 0.066 | 0.035 | 0.035 | |||

| (0.049) | (0.063) | (0.063) | ||||

| POS | −0.430 | ** | −0.515 | *** | −0.181 | |

| (0.027) | (0.036) | (0.138) | ||||

| Surface acting | 0.225 | *** | 0.582 | *** | ||

| (0.036) | (0.155) | |||||

| Deep acting | 0.057 | * | 0.196 | |||

| (0.032) | (0.153) | |||||

| Surface acting POS | −0.097 | ** | ||||

| (0.039) | ||||||

| Deep acting POS | −0.036 | |||||

| (0.037) | ||||||

| Constant | 3.247 | *** | 3.384 | *** | 2.122 | *** |

| (0.120) | (0.223) | (0.562) | ||||

| R-squared | 0.181 | 0.217 | 0.232 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, J.; Moon, K.-K. Exploring the Effect of Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from Korean Firefighters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054379

Lim J, Moon K-K. Exploring the Effect of Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from Korean Firefighters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054379

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Jaeyoung, and Kuk-Kyoung Moon. 2023. "Exploring the Effect of Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from Korean Firefighters" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054379

APA StyleLim, J., & Moon, K.-K. (2023). Exploring the Effect of Emotional Labor on Turnover Intention and the Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support: Evidence from Korean Firefighters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054379