Psychometric Characteristics of the Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory in Older Adults Living in a Middle-Income Country

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample and Setting

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Measurements

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Item Descriptive Analysis and Scale Scores

3.3. Psychometric Analysis of the Self-Care Maintenance Scale

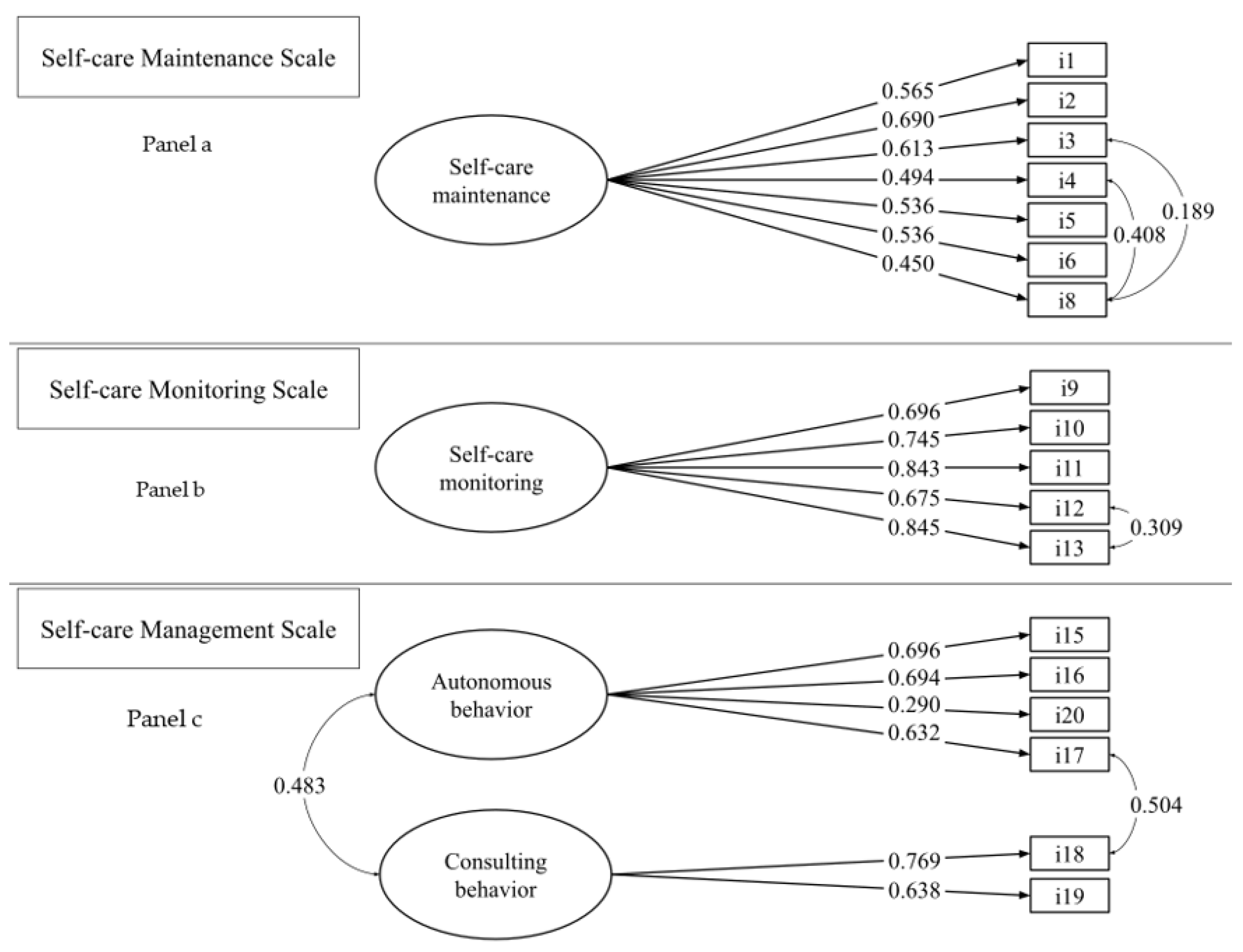

3.3.1. Dimensionality

3.3.2. Scale Internal Consistency Reliability

3.4. Psychometric Analysis of the Self-Care Monitoring Scale

3.4.1. Dimensionality

3.4.2. Scale Internal Consistency Reliability

3.5. Psychometric Analysis of the Self-Care Management Scale

3.5.1. Dimensionality

3.5.2. Scale Internal Consistency Reliability

3.6. Construct Validity through Hypothesis Testing

3.7. Measurement Errors of the SC-CII

4. Discussion

4.1. Dimensionality

4.2. Scale Internal Consistency Reliability

4.3. Construct Validity Testing

4.4. Measurement Errors of the SC-CII

4.5. Strengths and Limits

4.6. Implication for Clinical Practice and Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Palmer, A.J.; Cocker, F.; Sanderson, K. Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in a nationally representative population sample: Implications of count versus cluster method for defining multimorbidity on HRQoL. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. W.H.O. Non Communicable Diseases. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Aodeng, S.; Tanimoto, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Han, J.; Wang, B.; Yu, L.; Kono, K. Quality of life (QOL) of the community-dwelling elderly and associated factors: A population-based study in urban areas of China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 60, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajat, C.; Stein, E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. W.H.O. Self-Care Interventions for Health. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/self-care-health-interventions#:~:text=Self%2Dcare%20interventions%20include%20evidence,with%20or%20without%20health%20worker (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Riegel, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Strömberg, A. A middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. ANS. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2012, 35, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Dunbar, S.B.; Fitzsimons, D.; Freedland, K.E.; Lee, C.S.; Middleton, S.; Stromberg, A.; Vellone, E.; Webber, D.E.; Jaarsma, T. Self-care research: Where are we now? Where are we going? Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchieri, A.; Riegel, B.; D’Agostino, F.; Rocco, G.; Fida, R.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Describing self-care in Italian adults with heart failure and identifying determinants of poor self-care. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 14, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnault, D.S. Defining and Theorizing About Culture: The Evolution of the Cultural Determinants of Help-Seeking, Revised. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Lee, C.S.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; De Geest, S.; Potashnik, S.; Patey, M.; Sayers, S.L.; Goldberg, L.R.; Weintraub, W.S. Predictors of objectively measured medication nonadherence in adults with heart failure. Circulation. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraja, F.; Kraja, B.; Mone, I.; Harizi, I.; Babameto, A.; Burazeri, G. Self-reported Prevalence and Risk Factors of Non-communicable Diseases in the Albanian Adult Population. Med. Arch. 2016, 70, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentell, T.L.; Ylli, A.; Pirkle, C.M.; Qirjako, G.; Xinxo, S. Promoting a Culture of Prevention in Albania: The “Si Je?” Program. Prev. Sci. 2021, 22, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, Q.; Duli, M.; Burazeri, G.; Toci, D.; Brand, H.; Toci, E. Health Literacy and Blood Glucose Level in Transitional Albania. Front. Public Health. 2020, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalo, R. The Association between Social Integration, Coping Mechanisms and Anxiety in Patients with NonCommunicable Diseases. In Proceedings of the World Lumen Congress 2021, Iasi, Romania, 26–30 May 2021; Volume 17, pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrani, J.; Schindler, C.; Wyss, K. Health Seeking Behavior Among Adults and Elderly With Chronic Health Condition(s) in Albania. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 616014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B. Self-Care Measures. Available online: https://self-care-measures.com (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- De Maria, M.; Matarese, M.; Strömberg, A.; Ausili, D.; Vellone, E.; Jaarsma, T.; Osokpo, O.H.; Daus, M.M.; Riegel, B.; Barbaranelli, C. Cross-cultural assessment of the Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory: A psychometric evaluation. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Barbaranelli, C.; Sethares, K.A.; Daus, M.; Moser, D.K.; Miller, J.L.; Haedtke, C.A.; Feinberg, J.L.; Lee, S.; Stromberg, A.; et al. Development and initial testing of the self-care of chronic illness inventory. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; De Maria, M.; Barbaranelli, C.; Matarese, M.; Ausili, D.; Stromberg, A.; Vellone, E.; Jaarsma, T. Symptom Recognition as a Mediator in the Self-Care of Chronic Illness. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 883299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.S.; De Maria, M.; Barbaranelli, C.; Vellone, E.; Matarese, M.; Ausili, D.; Rejane, R.E.; Osokpo, O.H.; Riegel, B. Cross-cultural applicability of the Self-Care Self-Efficacy Scale in a multi-national study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, B.; Nahm, E.S. Reliability and validity testing of the revised 12-item Short-Form Health Survey in older adults. J. Nurs. Meas. 2001, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, L.L.; Fisher, J.D. Use of the 12-item short-form (SF-12) Health Survey in an Australian heart and stroke population. Qual. Life Res. 1999, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, M.; Tagliabue, S.; Ausili, D.; Vellone, E.; Matarese, M. Perceived social support and health-related quality of life in older adults who have multiple chronic conditions and their caregivers: A dyadic analysis. Soc. Sci. Med 2020, 262, 113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, H.G.; Kitko, L.; Hupcey, J.E. Dyadic heart failure care types: Qualitative evidence for a novel typology. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, E37–E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.G.; Hupcey, J.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Vellone, E.; Riegel, B. Heart Failure Care Dyadic Typology: Initial Conceptualization, Advances in Thinking, and Future Directions of a Clinically Relevant Classification System. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaranelli, C.; Lee, C.S.; Vellone, E.; Riegel, B. The problem with Cronbach’s Alpha: Comment on Sijtsma and van der Ark (2015). Nurs. Res. 2015, 64, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, M.; Clari, M.; De Marinis, M.G.; Barbaranelli, C.; Ivziku, D.; Piredda, M.; Riegel, B. The Self-Care in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Inventory: Development and Psychometric Evaluation. Eval. Health Prof. 2020, 43, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Barbaranelli, C.; Carlson, B.; Sethares, K.A.; Daus, M.; Moser, D.K.; Miller, J.; Osokpo, O.H.; Lee, S.; Brown, S.; et al. Psychometric Testing of the Revised Self-Care of Heart Failure Index. J. Cardiovasc. 2019, 34, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E.; De Maria, M.; Iovino, P.; Barbaranelli, C.; Zeffiro, V.; Pucciarelli, G.; Durante, A.; Alvaro, R.; Riegel, B. The Self-Care of Heart Failure Index version 7.2: Further psychometric testing. Res. Nurs. Health 2020, 43, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, M.; Vellone, E.; Ausili, D.; Alvaro, R.; Di Mauro, S.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.; Matarese, M. Self-care of patient and caregiver Dyads in multiple chronic conditions: A LongITudinal studY (SODALITY) protocol. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, M.; Fabrizi, D.; Luciani, M.; Caruso, R.; Di Mauro, S.; Riegel, B.; Barbaranelli, C.; Ausili, D. Further Evidence of Psychometric Performance of the Self-care of Diabetes Inventory in Adults with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Ann. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus. In Handbook of Item Response Theory; Muthén, L., Ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Meade, A.W.; Johnson, E.C.; Braddy, P.W. Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 568–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. A Review and Synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: Suggestions, Practices, and Recommendations for Organizational Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2000, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, T. Scale Construction and Development Using Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 472–492. [Google Scholar]

- De Maria, M.; Ferro, F.; Ausili, D.; Buck, H.G.; Vellone, E.; Matarese, M. Characteristics of dyadic care types among patients living with multiple chronic conditions and their informal caregivers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4768–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 12, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D. Standard Error vs. Standard Error of Measurement. Available online: http://hosted.jalt.org/test/ (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Beckerman, H.; Roebroeck, M.E.; Lankhorst, G.J.; Becher, J.G.; Bezemer, P.D.; Verbeek, A.L. Smallest real difference, a link between reproducibility and responsiveness. Qual. Life Res. 2001, 10, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weijters, B.; Geuens, M.; Schillewaert, N. The proximity effect: The role of inter-item distance on reverse-item bias. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Issues in the Application of Covariance Structure Analysis: A Further Comment. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 9, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. Issues in the Application of Covariance Structure Analysis: A Comment. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 9, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe-Alamah, M.R.M.H.B. Leininger’s Transcultural Nursing Concepts, Theories, Research, & Practice, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Osokpo, O.; Riegel, B. Cultural factors influencing self-care by persons with cardiovascular disease: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E.; Lorini, S.; Ausili, D.; Alvaro, R.; Di Mauro, S.; De Marinis, M.G.; Matarese, M.; De Maria, M. Psychometric characteristics of the caregiver contribution to self-care of chronic illness inventory. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2434–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Dickson, V.V.; Faulkner, K.M. The Situation-Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self-Care: Revised and Updated. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausili, D.; Barbaranelli, C.; Rossi, E.; Rebora, P.; Fabrizi, D.; Coghi, C.; Luciani, M.; Vellone, E.; Di Mauro, S.; Riegel, B. Development and psychometric testing of a theory-based tool to measure self-care in diabetes patients: The Self-Care of Diabetes Inventory. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2017, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, G.; Vellone, E.; Sciara, S.; Stievano, A.; Proietti, M.G.; Manara, D.F. Two new tools for self-care in ostomy patients and their informal caregivers: Psychosocial, clinical, and operative aspects. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 2018, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, M.; Iovino, P.; Lorini, S.; Ausili, D.; Matarese, M.; Vellone, E. Development and Psychometric Testing of the Caregiver Self-Efficacy in Contributing to Patient Self-Care Scale. Value Health 2021, 24, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovino, P.; De Maria, M.; Matarese, M.; Vellone, E.; Ausili, D.; Riegel, B. Depression and self-care in older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A multivariate analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, L.; Killela, M.K.; Reyes, B.L.; Santos, K.M.B.; Torres, V.; Huang, C.C.; Jacob, E. Self-Management, Self-Efficacy, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Children with Chronic Illness and Medical Complexity. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2020, 34, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, A.; Hunt, K.; Smith, S.; Wyke, S. Does gender matter? An analysis of men’s and women’s accounts of responding to symptoms of lung cancer. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 191, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.4 (6.4) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 134 (53.6) | |

| Female | 116 (46.4) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/partnered | 196 (78.4) | |

| Single | 3 (1.2) | |

| Widow/divorced | 51 (20.4) | |

| Level of education | ||

| 0–8 years | 155 (62) | |

| ≥9 years | 95 (38) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 9 (3.6) | |

| Unemployed/retired | 241 (96.4) | |

| Perceived income adequacy | ||

| Less than needed | 16 (6.4) | |

| Enough for living | 200 (80.0) | |

| More than needed | 34 (13.6) | |

| Number of chronic conditions | 2.5 (0.69) | |

| Patient chronic conditions | ||

| Hypertension | 219 (87.6) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 185 (74.0) | |

| Heart failure | 112 (44.8) | |

| COPD | 32 (12.8) | |

| Kidney disease | 20 (8.0) | |

| Arthritis | 20 (8.0) | |

| Other | 28 (11.2) | |

| Living with | ||

| Spouse/partner | 195 (78.0) | |

| Child | 125 (50.0) | |

| Grandchildren | 75 (30.0) | |

| Son/daughter-in-law | 82 (32.8) | |

| Other | 5 (2.0) |

| Items | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-care Maintenance scale (N = 250) | ||||

| 1. Make sure to get enough sleep? | 4.03 | 0.944 | −0.746 | 0.179 |

| 2. Try to avoid getting sick (e.g., flu shot, wash your hands)? | 4.41 | 0.729 | −0.873 | −0.373 |

| 3. Do physical activity (e.g., take a brisk walk, use the stairs)? | 3.37 | 1.281 | −0.206 | −0.988 |

| 4. Eat a special diet? | 3.45 | 1.177 | −0.335 | −0.574 |

| 5. See your healthcare provider for routine health care? | 4.20 | 0.875 | −0.608 | −0.886 |

| 6. Take prescribed medicines without missing a dose? | 4.74 | 0.476 | −1.524 | 1.308 |

| 8. Manage stress? | 2.94 | 1.251 | 0.121 | −0.843 |

| Self-care Monitoring scale (N = 250) | ||||

| 9. Monitor your condition? | 4.11 | 0.881 | −0.707 | −0.133 |

| 10. Pay attention to changes in how you feel? | 3.98 | 0.899 | −0.420 | −0.610 |

| 11. Monitor for medication side effects? | 4.00 | 0.944 | −0.452 | −0.907 |

| 12. Monitor whether you tire more than usual doing normal activities? | 3.96 | 0.956 | −0.619 | −0.196 |

| 13. Monitor for symptoms? | 3.96 | 0.971 | −0.528 | −0.662 |

| 14. If you had symptoms in the past month, how quickly did you recognize it as a symptom of your illness? | 2.85 | 1.473 | −0.001 | −1.058 |

| Self-care Management scale (N = 226) | ||||

| 15. When you have symptoms, how likely are you to … change what you eat or drink to make the symptom decrease or go away? | 3.62 | 1.006 | −0.200 | −0.487 |

| 16. Change your activity level (e.g., slow down, rest)? | 3.90 | 0.972 | −0.556 | −0.162 |

| 17. Take a medicine to make the symptom decrease or go away? | 4.28 | 0.869 | −0.871 | −0.372 |

| 18. Tell your healthcare provider about the symptom at the next office visit? | 4.39 | 0.783 | −1.044 | 0.156 |

| 19. Call your healthcare provider for guidance? | 3.92 | 1.136 | −0.832 | −0.144 |

| 20. Think of a treatment you used the last time you had symptoms. Did the treatment you used make you feel better? | 3.38 | 1.078 | −0.236 | −0.354 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-care maintenance | - | 0.500 | 0.561 | 0.600 | −0.289 | 0.487 | 0.325 |

| 2. Self-care monitoring | - | 0.631 | 0.668 | −0.323 | 0.567 | 0.442 | |

| 3. Self-care management | - | 0.696 | −0.245 | 0.557 | 0.435 | ||

| 4. Self-care self-efficacy | - | −0.245 | 0.664 | 0.567 | |||

| 5. PHQ-9 | - | −0.657 | −0.456 | ||||

| 6. MCS | - | 0.776 | |||||

| 7. PCS | - |

| Total Sample | Female Patient (N = 116, 46.6%) | Male Patient (N = 134, 56.6%) | T Test p-Value | Patient-Oriented Dyadic Care Type (N = 38, 15.2%) | Caregiver-Oriented Dyadic Care Type (N = 31, 12.4%) | T Test p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Self-care maintenance (N = 250) | 72.0 (16.0) | 69.7 (15.4) | 74.1 (16.3) | 0.004 | 75.4 (15.5) | 55.8 (11.6) | 0.002 |

| Self-care monitoring (N = 250) | 75.0 (19.1) | 73.5 (17.8) | 76.3 (20.3) | 0.002 | 79.2 (18.4) | 61.5 (19.5) | 0.003 |

| Self-care management (N = 226) | 72.4 (15.9) | 72.5 (14.8) | 72.1 (16.9) | 0.006 | 68.8 (16.7) | 61.6 (16.5) | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arapi, A.; Vellone, E.; Ivziku, D.; Duka, B.; Taci, D.; Notarnicola, I.; Stievano, A.; Prendi, E.; Rocco, G.; De Maria, M. Psychometric Characteristics of the Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory in Older Adults Living in a Middle-Income Country. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064714

Arapi A, Vellone E, Ivziku D, Duka B, Taci D, Notarnicola I, Stievano A, Prendi E, Rocco G, De Maria M. Psychometric Characteristics of the Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory in Older Adults Living in a Middle-Income Country. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064714

Chicago/Turabian StyleArapi, Alta, Ercole Vellone, Dhurata Ivziku, Blerina Duka, Dasilva Taci, Ippolito Notarnicola, Alessandro Stievano, Emanuela Prendi, Gennaro Rocco, and Maddalena De Maria. 2023. "Psychometric Characteristics of the Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory in Older Adults Living in a Middle-Income Country" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064714

APA StyleArapi, A., Vellone, E., Ivziku, D., Duka, B., Taci, D., Notarnicola, I., Stievano, A., Prendi, E., Rocco, G., & De Maria, M. (2023). Psychometric Characteristics of the Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory in Older Adults Living in a Middle-Income Country. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064714