Factors Associated with the Quality-of-Life of Young Unpaid Carers: A Systematic Review of the Evidence from 2003 to 2019

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligible Studies, and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

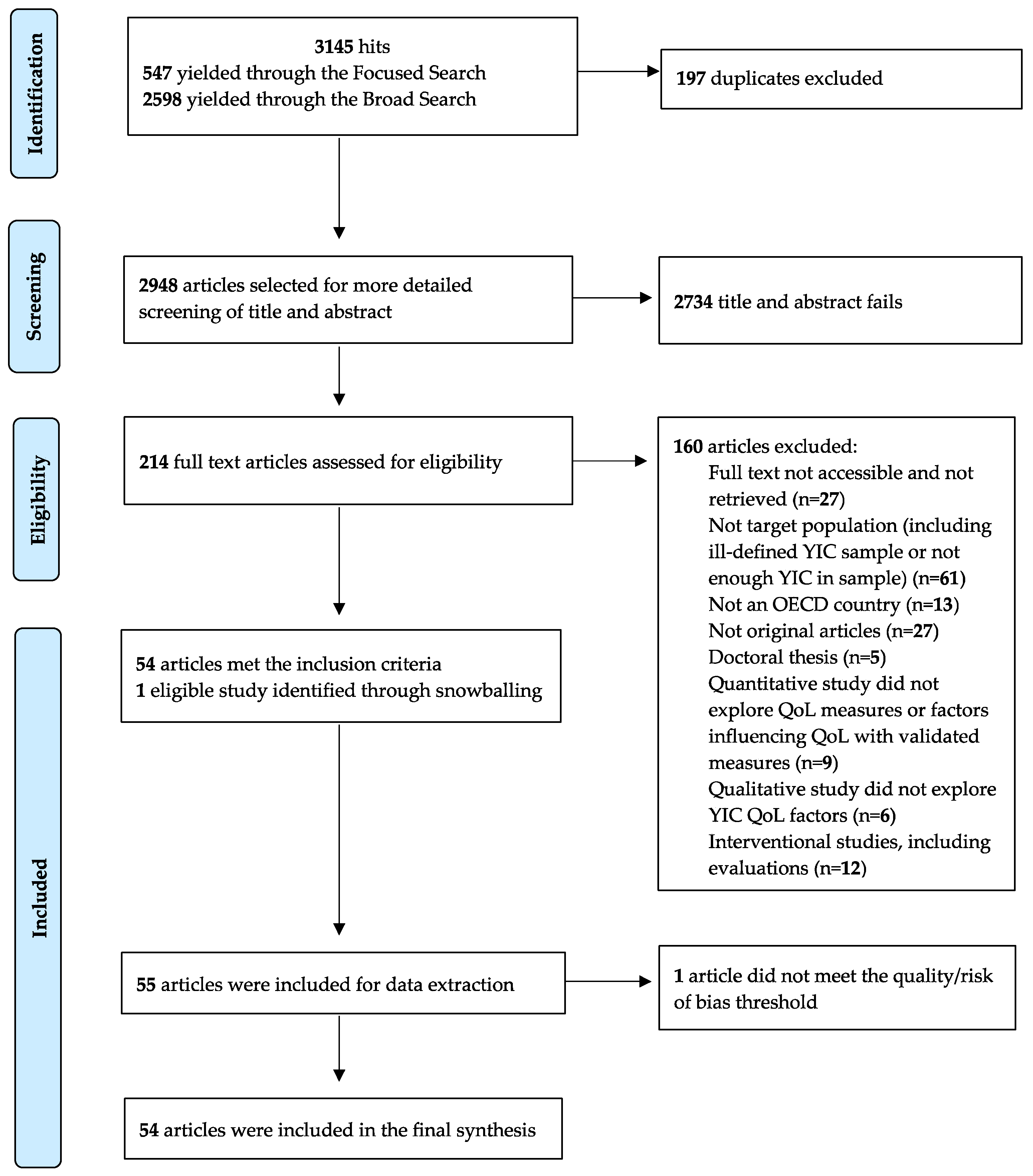

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study and Participant Characteristics

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Narrative Synthesis

3.5. Perceived Normality of Role and Identifying as a Carer

3.6. Social Support from Formal and Unpaid Networks

3.7. Caring Demands and Their Impact

3.8. Coping Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Results and Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Census Analysis: Unpaid Care in England and Wales, 2011 and Comparison with 2001. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthcaresystem/articles/2011censusanalysisunpaidcareinenglandandwales2011andcomparisonwith2001/2013-02-15 (accessed on 31 July 2019).

- NHS England. Carer Facts—Why Investing in Carers Matters. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/comm-carers/carer-facts/ (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Buhse, M. Assessment of caregiver burden in families of persons with Multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2008, 40, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settineri, S.; Rizzo, A.; Liotta, M.; Mento, C. Caregiver’s burden and quality of life: Caring for physical and mental illness. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2014, 7, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nordin, A.A.; Hairi, F.M.; Choo, W.Y.; Hairi, N.N. Care Recipient Multimorbidity and Health Impacts on Informal Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2018, 59, e611–e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bom, J.; Bakx, P.; Schut, F.; van Doorslaer, E. The Impact of Informal Caregiving for Older Adults on the Health of Various Types of Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2018, 59, e629–e642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenwood, N.; Mezey, G.; Smith, R. Social exclusion in adult informal carers: A systematic narrative review of the experiences of informal carers of people with dementia and mental illness. Maturitas 2018, 112, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gardiner, C.; Brereton, L.; Frey, R.; Wilkinson-Meyers, L.; Gott, M. Exploring the financial impact of caring for family members receiving palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review of the literature. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, R.V.; Powers, S.M.; Bisconti, T.L. Positive Aspects of the Caregiving Experience: Finding Hope in the Midst of the Storm. Women Ther. 2016, 39, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, W.B.F.; Van Exel, N.J.A.; Van Den Berg, B.; Van Den Bos, G.A.M.; Koopmanschap, M.A. Process utility from providing informal care: The benefit of caring. Health Policy 2005, 74, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R.; Cook, T.B.; Martire, L.M.; Tomlinson, J.M.; Monin, J.K. Predictors and consequences of perceived lack of choice in becoming an informal caregiver. Aging Ment. Health 2012, 16, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharer, M.; Cluver, L.; Shields, J.J.; Ahearn, F.M.S. The power of siblings and caregivers: Under-explored types of social support among children affected by HIV and AIDS. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, S.; Murray, J.; Foley, B.; Atkins, L.; Schneider, J.; Mann, A. Predictors of institutionalisation in people with dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 1315–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Becker, S. Global perspectives on children’s unpaid caregiving in the family: Research and policy on “young carers” in the UK, Australia, the USA and sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Soc. Policy 2007, 7, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Care Act 2014: Transition to Adult Care and Support. Available online: https://www.proceduresonline.com/stockport/cs/pdfs/trans_adult_care.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Department of Health and Social Care. Carers Action Plan 2018 to 2020: Supporting Carers Today. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/713781/carers-action-plan-2018-2020.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2009, 7, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, N.; Page, T.E.; Daley, S.; Brown, A.; Bowling, A.; Basset, T.; Livingston, G.; Knapp, M.; Murray, J.; Banerjee, S. Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Peacock, R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. Br. Med. J. 2005, 331, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwon, Y.; Lemieux, M.; McTavish, J.; Wathen, N. Identifying and removing duplicate records from systematic review searches. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2015, 103, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018: User Guide. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/ (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2006; Volume 92. [Google Scholar]

- Leu, A.; Frech, M.; Jung, C. Young carers and young adult carers in Switzerland: Caring roles, ways into care and the meaning of communication. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.J.; Oyebode, J.R.; Allen, J.J. Having a father with young onset dementia: The impact on well-being of young people. Dementia 2009, 8, 455–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.G.; Adamson, E. Bounded agency in young carers’ lifecourse-stage domains and transitions. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 16, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, C.; Blaxland, M.; Cass, B. “So that’s how I found out I was a young carer and that I actually had been a carer most of my life”. Identifying and supporting hidden young carers. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, J.Y.; Larsen, D.; Brødsgaard, A. Striving for balance between caring and restraint: Young adults’ experiences with parental multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGibbon, M.; Spratt, T.; Davidson, G. Young Carers in Northern Ireland: Perceptions of and Responses to Illness and Disability within the Family. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 49, 1162–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolas, H.; Van Wersch, A.; Flynn, D. The well-being of young people who care for a dependent relative: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychol. Health 2007, 22, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, L.; Cushway, D.; Cassidy, T. Children’s perceptions and experiences of care giving: A focus group study. Couns. Psychol. Quartely 2007, 20, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, A.K.; Coberly, B.; Diesel, S.J. Childhood Caregiving Roles, Perceptions of Benefits, and Future Caregiving Intentions Among Typically Developing Adult Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boumans, N.P.G.; Dorant, E. A cross-sectional study on experiences of young adult carers compared to young adult noncarers: Parentification, coping and resilience. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.J.; Luthar, S.S. Defining Characteristics and Potential Consequences of Caretaking Burden Among Children Living in Urban Poverty. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2007, 77, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, N.; Stainton, T.; Jackson, S.; Cheung, W.Y.; Doubtfire, S.; Webb, A. “Your friends don’t understand”: Invisibility and unmet need: In the lives of “young carers”. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2003, 8, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, K.R.; Fam, D.; Cook, C.; Pearce, M.; Elliot, G.; Baago, S.; Rockwood, K.; Chow, T.W. When dementia is in the house: Needs assessment survey for young caregivers. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 40, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stamatopoulos, V. The young carer penalty: Exploring the costs of caregiving among a sample of Canadian youth. Child Youth Serv. 2018, 39, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruhauf, C.A.; Jarrott, S.E.; Allen, K.R. Grandchildren’s perceptions of caring for grandparents. J. Fam. Issues 2006, 27, 887–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meltzer, A. “I couldn’t just entirely be her sister”: The relational and social policy implications of care between young adult siblings with and without disabilities. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 20, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, E.; Stott, J.; Spector, A. “Just helping”: Children living with a parent with young onset dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, E.; O’Connor, M.; Howell, J. “Something that happens at home and stays at home”: An exploration of the lived experience of young carers in Western Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostman, M. Interviews with children of persons with a severe mental illness—Investigating their everyday situation. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2008, 62, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; McArthur, M. We’re all in it together: Supporting young carers and their families in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2007, 15, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruhauf, C.A.; Orel, N.A. Developmental issues of grandchildren who provide care to grandparents. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008, 67, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, M.J.; Pakenham, K.I. Youth adjustment to parental illness or disability: The role of illness characteristics, caregiving, and attachment. Psychol. Health Med. 2010, 15, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Bursnall, S.; Chiu, J.; Cannon, T.; Okochi, M. The psychosocial impact of caregiving on young people who have a parent with an illness or disability: Comparisons between young caregivers and noncaregivers. Rehabil. Psychol. 2006, 51, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M. “I realised that I wasn’t alone”: The views and experiences of young carers from a social capital perspective. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kavanaugh, M.S.; Noh, H.; Studer, L. “It’d be nice if someone asked me how I was doing. Like, ‘cause I will have an answer”: Exploring support needs of young carers of a parent with Huntington’s disease. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2015, 10, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Ahlstrom, B.H.; Krevers, B.; Sjostrom, N.; Skarsater, I. Support for young informal carers of persons with mental illness: A mixed-method study. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 34, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järkestig-Berggren, U.; Bergman, A.; Eriksson, M.; Priebe, G. Young carers in Sweden—A pilot study of care activities, view of caring, and psychological well-being. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2019, 24, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, A.; Heyman, B. “The sooner you can change their life course the better”: The time-framing of risks in relationship to being a young carer. Health Risk Soc. 2013, 15, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yahav, R.; Vosburgh, J.; Miller, A. Emotional responses of children and adolescents to parents with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2005, 11, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzing-Blau, S.; Schnepp, W. Young carers in Germany: To live on as normal as possible—A grounded theory study. BMC Nurs. 2008, 7, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fraser, E.; Pakenham, K.I. Resilience in children of parents with mental illness: Relations between mental health literacy, social connectedness and coping, and both adjustment and caregiving. Psychol. Health Med. 2009, 14, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; McArthur, M.; Noble-Carr, D. Different but the same? Exploring the experiences of young people caring for a parent with an alcohol or other drug issue. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieh, D.S.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Oort, F.J.; Meijer, A.M. Risk factors for problem behavior in adolescents of parents with a chronic medical condition. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 21, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moyson, T.; Roeyers, H. “The overall quality of my life as a sibling is all right, but of course, it could always be better”. Quality of life of siblings of children with intellectual disability: The siblings’ perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, C.; Hunt, G.G.; Halper, D.; Hart, A.Y.; Lautz, J.; Gould, D.A. Young adult caregivers: A first look at an unstudied population. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 2071–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eley, S. “If they don’t recognize it, you’ve got to deal with it yourself”: Gender, young caring and educational support. Gend. Educ. 2004, 16, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Millenaar, J.K.; van Vliet, D.; Bakker, C.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.F.J.; Koopmans, R.T.C.M.; Verhey, F.R.J.; de Vugt, M.E. The experiences and needs of children living with a parent with young onset dementia: Results from the NeedYD study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cree, V.E. Worries and problems of young carers: Issues for mental health. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2003, 8, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K. Happiness and Well-Being of Young Carers: Extent, Nature and Correlates of Caring Among 10 and 11 Year Old School Children. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Cox, S. The effects of parental illness and other ill family members on youth caregiving experiences. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spratt, T.; McGibbon, M.; Davidson, G. Using Adverse Childhood Experience Scores to Better Understand the Needs of Young Carers. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2018, 48, 2346–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cassidy, T.; Giles, M.; McLaughlin, M. Benefit finding and resilience in child caregivers. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Wade, D.; Howie, L.; McGorry, P. The positive and negative experiences of caregiving for siblings of young people with first episode psychosis. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, J.; Bayless, S. How caring for a parent affects the psychosocial development of the young. Nurs. Child. Young People 2013, 25, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakman, Y.; Chalmers, H. Psychosocial comparison of carers and noncarers. Child Youth Serv. 2019, 40, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M. Children and Adolescents Providing Care to a Parent with Huntington’s Disease: Disease Symptoms, Caregiving Tasks and Young Carer Well-Being. Child Youth Care Forum 2014, 43, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Cohen, D.; Siskowski, C.; Toyinbo, P. The Relationship Between Family Caregiving and the Mental Health of Emerging Young Adult Caregivers. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 44, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.; Sempik, J. Young Adult Carers: The Impact of Caring on Health and Education. Child. Soc. 2019, 33, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sieh, D.S.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Meijer, A.M. Differential Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronically Ill and Healthy Parents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lakman, Y.; Chalmers, H.; Sexton, C. Young carers’ educational experiences and support: A roadmap for the development of school policies to foster their academic success. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 63, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Siskowski, C. Young caregivers: Effect of family health situations on school performance. J. Sch. Nurs. 2006, 22, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Cox, S. The Effects of Parental Illness and Other Ill Family Members on the Adjustment of Children. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 48, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kallander, E.K.; Weimand, B.M.; Becker, S.; Van Roy, B.; Hanssen-Bauer, K.; Stavnes, K.; Faugli, A.; Kufås, E.; Ruud, T. Children with ill parents: Extent and nature of caring activities. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Cox, S. Comparisons between youth of a parent with MS and a control group on adjustment, caregiving, attachment and family functioning. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff, C.; Mandleco, B.; Dyches, T.T.; Coverston, C.R.; Roper, S.O.; Freeborn, D. Perspectives of adolescent siblings of children with Down syndrome who have multiple health problems. J. Fam. Nurs. 2012, 18, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakenham, K.I.; Chiu, J.; Bursnall, S.; Cannon, T. Relations between social support, appraisal and coping and both positive and negative outcomes in young carers. J. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, H.M.; Bell, J.F.; Whitney, R.L.; Ridberg, R.A.; Reed, S.C.; Vitaliano, P.P. Social Determinants of Health: Underreported Heterogeneity in Systematic Reviews of Caregiver Interventions. Gerontologist 2020, 60, S14–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schlarmann, J.G.; Metzing-Blau, S.; Schnepp, W. The use of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children and adolescents as an outcome criterion to evaluate family oriented support for young carers in Germany: An integrative review of the literature. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, D.; Holder, J.; Netten, A. Personal Social Services Survey of Adult Carers in England-2009-10: Survey Development Project Technical Report 2010. Available online: https://www.pssru.ac.uk (accessed on 6 August 2019).

- Al-Janabi, H.; Coast, J.; Flynn, T.N. What do people value when they provide unpaid care for an older person? A meta-ethnography with interview follow-up. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brouwer, W.B.F.; van Exel, N.J.A.; van Gorp, B.; Redekop, W.K. The CarerQol instrument: A new instrument to measure care-related quality of life of informal caregivers for use in economic evaluations. Qual. Life Res. 2006, 15, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focused Search Strategy | Broad Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| Medline Ovid | |

| young carer*.mp [53 hits] young caregiver*.mp. [24 hits] young adult carer*.mp. [4 hits] young adult caregiver*.mp. [4 hits] caregiving youth.mp. [4 hits] 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 [78 hits] limit 6 to English language [76 hits] | Caregiver*/ [33,376 hits] limit 1 to (“preschool child (2 to 5 years)” or “child (6 to 12 years)” or “adolescent (13 to 18 years)” or “young adult (19 to 24 years)”) [9474 hits] “Child of impaired parents” [5067 hits] 2 or 3 [14,428 hits] grandparent.mp. or grandparents/ [907 hits] parents/or fathers/or mothers/or single parent/ [103,820 hits] Sibling*/or brother*/or sister*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] [43,349 hits] 5 or 6 or 7 [146,542 hits] “Quality of life”/or qol/or ql/or hrqol/or hrql/or “health related quality of life”/or “health-related quality of life”/or life quality/or wellbeing/or life satisfaction/or “CarerQol”/or “SCRQol”/or “social care related quality of life”/ [273,424 hits] “cost of illness”/or caregiver burden.mp. [27043 hits] attitude/or motivation/or willingness/or perception/or need/ [137,924 hits] 9 or 10 or 11 [634,680 hits] 4 and 8 and 12 [859 hits] limit 18 to English language [824 hits] |

| Scales and Their Domains/Systematic Review Themes | Perceived Normality of Role and Identifying as a Carer | Social Support from Formal and Unpaid Networks | Caring Demands and Their Impact | Coping Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carer-QoL | - | Support Relational problems | Social, mental, and physical health problems Financial problems | Fulfilment |

| ASCOT-Carer | Control over daily life | Feeling supported and encouraged | Occupation, personal safety | Space and time to be yourself |

| Social participation | Self-care | |||

| CES | Control over caring | Support from family and friends | - | Activities outside of caring |

| Assistance from organisations and the government | ||||

| Getting on with the care-recipient | Fulfilment from caring | |||

| Adult Carer-QoL | Caring choice | Support for caring | Caring stress | Sense of value |

| Ability to care | Personal growth | |||

| Carer satisfaction | Money matters | Carer satisfaction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bou, C. Factors Associated with the Quality-of-Life of Young Unpaid Carers: A Systematic Review of the Evidence from 2003 to 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064807

Bou C. Factors Associated with the Quality-of-Life of Young Unpaid Carers: A Systematic Review of the Evidence from 2003 to 2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064807

Chicago/Turabian StyleBou, Camille. 2023. "Factors Associated with the Quality-of-Life of Young Unpaid Carers: A Systematic Review of the Evidence from 2003 to 2019" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064807