Impact of an Enhanced Transtheoretical Model Intervention (ETMI) Workshop on the Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Low Back Pain of Primary Care Physicians in the Israeli Navy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Attitudes and Beliefs towards LBP

- Limitations on sessions—Four items exploring practitioners’ policy towards limiting the number and length of patient–clinician encounters per episode of care (min–max = 4 to 28, where 28 = support unlimited sessions).

- Psychological—Four items measuring practitioners’ willingness to explore patients’ psychological issues (min–max = 4 to 28, where 28 = support psychological approaches).

- Connection to the healthcare system—Three items measuring attitudes towards the healthcare system and its available services and policies (min–max = 3 to 21, where 21 = feel connected).

- Confidence and concern—Two items measuring practitioners’ confidence in themselves and others regarding treatment and clinical limitations (min–max = 2 to 14, where 14 = confident).

- Re-activation—Three items exploring attitudes towards the return to work, daily activity, and increasing physical mobility (min–max = 3 to 21, where 21 = support re-activation).

- Biomedical—Three items concerning the belief that back pain has a structural cause as well as advice to restrict physical activity (min–max = 3 to 21, where 21 = support biomedical approach).

2.2.2. Clinical Behavior

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

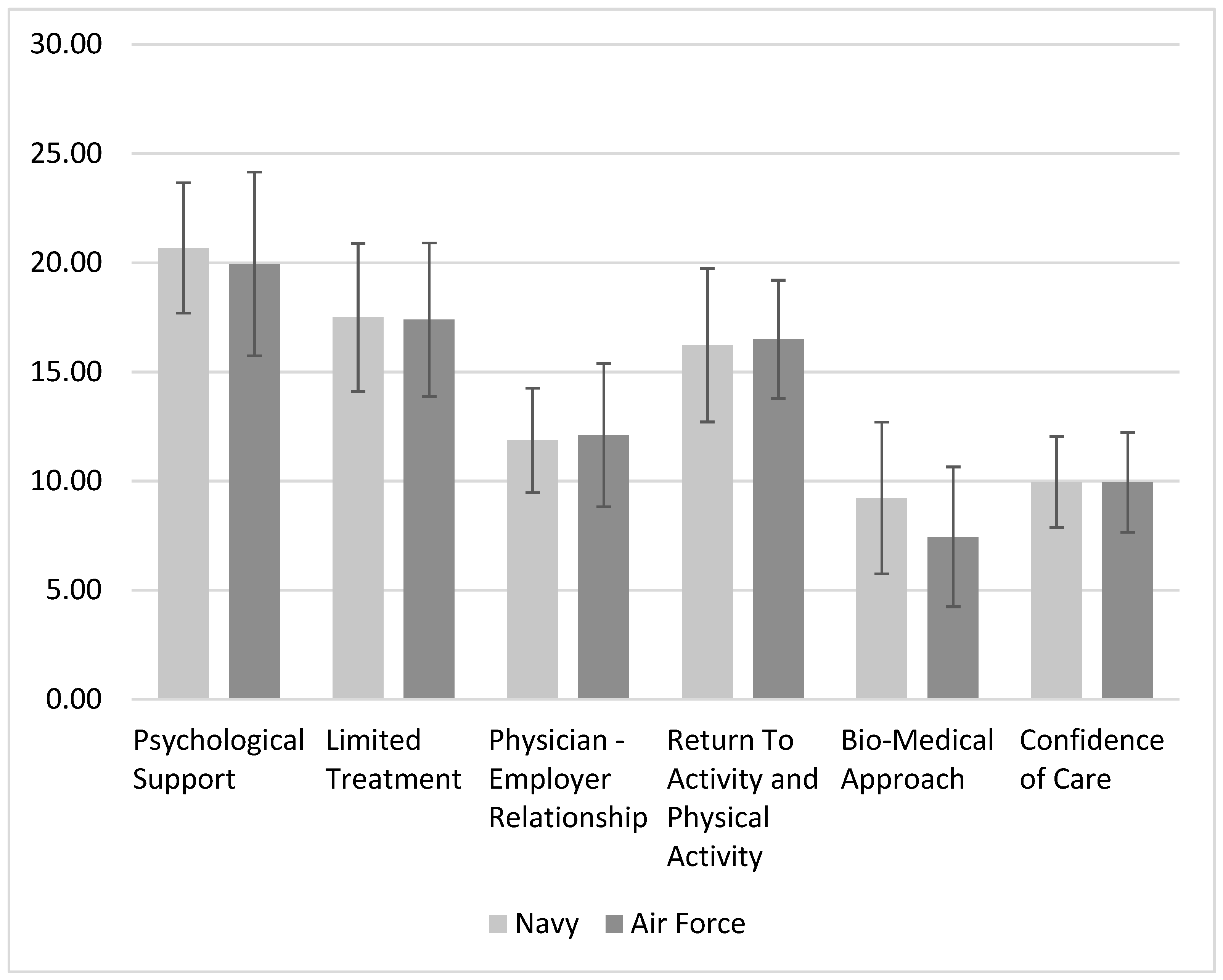

3.1. Pre-Workshop

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Associations between Attitudes and Clinical Behavior

3.1.3. Primary Component Analysis

3.2. Post-Workshop

4. Discussion

4.1. Physicians’ Attitudes and Clinical Behavior—Before ETMI Workshop

4.1.1. ABS-mp Correlations

4.1.2. PCA

4.2. Physicians’ Attitudes and Clinical Behavior—Post-ETMI Workshop

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buchbinder, R.; van Tulder, M.; Öberg, B.; Costa, L.M.; Woolf, A.; Schoene, M.; Croft, P. Low back pain: A call for action. Lancet 2018, 391, 2384–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, N.E.; Anema, J.R.; Cherkin, D.; Chou, R.; Cohen, S.P.; Gross, D.P.; Ferreira, P.H.; Fritz, J.M.; Koes, B.W.; Peul, W.; et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: Evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018, 391, 2368–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartvigsen, J.; Hancock, M.J.; Kongsted, A.; Louw, Q.; Ferreira, M.L.; Genevay, S.; Hoy, D.; Karppinen, J.; Pransky, G.; Sieper, J.; et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018, 391, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- el Barzouhi, A.; Vleggeert-Lankamp, C.L.A.M.; Lycklama à Nijeholt, G.J.; Van der Kallen, B.F.; van den Hout, W.B.; Jacobs, W.C.H.; Koes, B.W.; Peul, W.C. Magnetic resonance imaging in follow-up assessment of sciatica. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chou, R.; Fu, R.; Carrino, J.A.; Deyo, R.A. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farre, A.; Rapley, T. The new old (And old new) medical model: Four decades navigating the biomedical and psychosocial understandings of health and illness. Healthcare 2017, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buchbinder, R.; Underwood, M.; Hartvigsen, J.; Maher, C.G. The Lancet Series call to action to reduce low value care for low back pain: An update. Pain 2020, 161, S57–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traeger, A.C.; Buchbinder, R.; Elshaug, A.G.; Croft, P.R.; Maher, C.G. Care for low back pain: Can health systems deliver? Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincus, T.; Vogel, S.; Santos, R.; Breen, A.; Foster, N.; Underwood, M. The attitudes to back pain scale in musculoskeletal practitioners (ABS-mp). Clin. J. Pain. 2006, 22, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.Z.; Childs, J.D.; Teyhen, D.S.; Wu, S.S.; Wright, A.C.; Dugan, J.L.; Robinson, M.E. Brief psychosocial education, not core stabilization, reduced incidence of low back pain: Results from the Prevention of Low Back Pain in the Military (POLM) cluster randomized trial. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knox, J.; Orchowski, J.; Scher, D.L.; Owens, B.D.; Burks, R.; Belmont, P.J. The incidence of low back pain in active duty United States military service members. Spine 2011, 36, 1492–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ben-Ami, N.; Chodick, G.; Mirovsky, Y.; Pincus, T.; Shapiro, Y. Increasing recreational physical activity in patients with chronic low back pain:a pragmatic controlled clinical trial. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017, 47, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canaway, A.; Pincus, T.; Underwood, M.; Shapiro, Y.; Chodick, G.; Ben-Ami, N. Is an enhanced behaviour change intervention cost-effective compared with physiotherapy for patients with chronic low back pain? Results from a multicentre trial in Israel. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nudelman, Y.; Pincus, T.; Shashua, A.; Ben Ami, N. Cross-cultural adaptation, validation and psychometric evaluation of the attitudes to back pain scale in musculoskeletal practitioners—Hebrew version. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2021, 56, 102463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahar, Y.; Goldstein, R.; Nudelman, Y.; Besor, O.; Ben-Ami, N. Can the enhanced transtheoretical model intervention (ETMI) impact the attitudes and beliefs regarding low back pain of family medicine Residents. IMAJ 2022, 24, 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ami, N.; Shapiro, Y.; Pincus, T. Outcomes in distressed patients with chronic low back pain: Subgroup analysis of a clinical trial. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Seaman, J., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Qaseem, A.; Wilt, T.J.; McLean, R.M.; Forciea, M.A. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliveira, C.B.; Maher, C.G.; Pinto, R.Z.; Traeger, A.C.; Lin, C.W.C.; Chenot, J.F.; van Tulder, M.; Koes, B.W. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: An updated overview. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 2791–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Husted, M.; Rossen, C.B.; Jensen, T.S.; Mikkelsen, L.R.; Rolving, N. Adherence to key domains in low back pain guidelines: A cross-sectional study of Danish physiotherapists. Physiother. Res. Int. 2020, 25, e1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traeger, A.; Buchbinder, R.; Harris, I.; Maher, C. Diagnosis and management of low-back pain in primary care. CMAJ 2017, 189, E1386–E1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, S.; Traeger, A.C.; Reed, B.; Hamilton, M.; O’Connor, D.A.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Bonner, C.; Buchbinder, R.; Maher, C.G. Clinician and patient beliefs about diagnostic imaging for low back pain: A systematic qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, I.A.; Malik, Q.; Carville, S.; Ward, S. Low back pain and sciatica: Summary of NICE guidance. Brows. J. Spec. 2017, 6748, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javalgi, R.; Joseph, W.B.; Gombeski, W.R.; Lester, J.A. How physicians make referrals. J. Health Care Mark. 1993, 13, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Intervention | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Mean | Number | Mean | p Value | ||

| Age, Mean(SD) | 22 | 32.64 (7.23) | 18 | 31.65 (9.03) | p = 0.706 | |

| Gender | Male | 18 | 81.80% | 8 | 44.40% | p = 0.014 |

| Female | 4 | 18.20% | 10 | 55.60% | ||

| Years of experience | 0–5 Years | 14 | 63.60% | 16 | 88.90% | p = 0.186 |

| 5–10 Years | 4 | 18.20% | 1 | 5.60% | ||

| Over 10 Years | 4 | 18.20% | 1 | 5.60% | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 0.83 | ||

| Isotopic Scan | 0.79 | ||

| MRI | 0.75 | ||

| X-Ray | 0.67 | ||

| ER referral | 0.66 | ||

| EMG | 0.66 | ||

| Benzo | 0.72 | ||

| Cannabis | 0.69 | ||

| Anti-Depressants | 0.64 | ||

| Dry Needling | 0.64 | ||

| Opiates | 0.60 | ||

| Manual Exam | −0.58 | ||

| Reassurance | −0.80 | ||

| OTC Pain Medication | 0.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Besor, O.; Brand, R.; Feldman, R.; Nudelman, Y.; Shahar, Y.; Finestone, A.S.; Ben Ami, N. Impact of an Enhanced Transtheoretical Model Intervention (ETMI) Workshop on the Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Low Back Pain of Primary Care Physicians in the Israeli Navy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064854

Besor O, Brand R, Feldman R, Nudelman Y, Shahar Y, Finestone AS, Ben Ami N. Impact of an Enhanced Transtheoretical Model Intervention (ETMI) Workshop on the Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Low Back Pain of Primary Care Physicians in the Israeli Navy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064854

Chicago/Turabian StyleBesor, Omri, Ronen Brand, Ron Feldman, Yaniv Nudelman, Yair Shahar, Aharon S. Finestone, and Noa Ben Ami. 2023. "Impact of an Enhanced Transtheoretical Model Intervention (ETMI) Workshop on the Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Low Back Pain of Primary Care Physicians in the Israeli Navy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064854

APA StyleBesor, O., Brand, R., Feldman, R., Nudelman, Y., Shahar, Y., Finestone, A. S., & Ben Ami, N. (2023). Impact of an Enhanced Transtheoretical Model Intervention (ETMI) Workshop on the Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Low Back Pain of Primary Care Physicians in the Israeli Navy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064854