Predictors of Anxiety in Romanian Generation Z Teenagers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Q1.1 | Q1.3 | Q1.4 | Q1.5 | Q1.6 | Q1.7 | Q1.8 | Q1.9 | Q1.10 | Q1.11 | Q1.12_1 | Q1.12_2 | Q1.12_3 | Q13_score | Q1.16 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1.1. | Pearson Correlation | 0.568 ** | 0.827 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.565 ** | 0.618 ** | 0.672 ** | 0.696 ** | 0.568 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.229 ** | 0.763 ** | 0.174 ** | −0.259 ** | −0.248 ** | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||

| Q1.3. | PC | 0.658 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.451 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.638 ** | 0.500 ** | 0.120 ** | 0.609 ** | 0.108 * | −0.203 ** | −0.161 ** | ||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||

| Q1.4. | PC | 0.610 ** | 0.615 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.723 ** | 0.758 ** | 0.615 ** | 0.734 ** | 0.232 ** | 0.791 ** | 0.145 ** | −0.256 ** | −0.231 ** | |||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||

| Q1.5. | PC | 0.698 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.631 ** | 0.452 ** | 0.200 ** | 0.587 ** | 0.144 ** | −0.241 ** | −0.139 ** | ||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||

| Q1.6. | PC | 0.464 ** | 0.672 ** | 0.535 ** | 0.601 ** | 0.496 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.129 ** | −0.195 ** | −0.089 * | |||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.035 | ||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||||

| Q1.7. | PC | 0.523 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.179 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.159 ** | −0.113 ** | −0.211 ** | ||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.000 | |||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||||

| Q1.8. | PC | 0.607 ** | 0.641 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.230 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.170 ** | −0.246 ** | −0.166 ** | |||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||||||

| Q1.9. | PC | 0.555 ** | 0.695 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.674 ** | 0.162 ** | −0.139 ** | −0.186 ** | ||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||||||

| Q1.10. | PC | 0.499 ** | 0.115 ** | 0.597 ** | 0.104 * | −0.151 ** | −0.130 ** | |||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.002 | ||||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||||||||

| Q1.11. | PC | 0.246 ** | 0.665 ** | 0.110 ** | −0.221 ** | −0.244 ** | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||||||||

| Q1.12_1 | PC | 0.456 ** | 0.346 ** | −0.171 ** | −0.192 ** | |||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||||||||||

| Q1.12_2 | PC | 0.297 ** | −0.280 ** | −0.242 ** | ||||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||||||||||

| Q1.12_3 | PC | −0.179 ** | −0.155 ** | |||||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | ||||||||||||||

| Q13_scor | PC | 0.385 ** | ||||||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | |||||||||||||||

| N | 558 | |||||||||||||||

| Q1.17 | Q1.18 | Q1.19 | Q1.20 | Q1.24 | Q1.26_1 | Q1.26_2 | Q1.26_3 | Q2.3. Age | Q2.4 | v1_tata | v2_risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1.1. | Pearson Correlation | −0.331 ** | −0.227 ** | −0.327 ** | −0.165 ** | −0.049 | 0.267 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.202 ** | −0.149 ** | −0.343 ** | 0.878 ** | −0.380 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.249 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.3. | PC | −0.234 ** | −0.113 ** | −0.190 ** | −0.068 | −0.101 * | 0.189 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.172 ** | −0.117 ** | −0.222 ** | 0.761 ** | −0.224 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.110 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.4. | PC | −0.335 ** | −0.163 ** | −0.283 ** | −0.158 ** | −0.074 | 0.264 ** | 0.698 ** | 0.174 ** | −0.119 ** | −0.297 ** | 0.919 ** | −0.336 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.079 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.5. | PC | −0.221 ** | −0.124 ** | −0.151 ** | −0.075 | −0.037 | 0.258 ** | 0.561 ** | 0.210 ** | −0.161 ** | −0.190 ** | 0.724 ** | −0.206 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 0.383 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.6. | PC | −0.204 ** | −0.093 * | −0.145 ** | −0.069 | −0.013 | 0.234 ** | 0.577 ** | 0.198 ** | −0.181 ** | −0.222 ** | 0.701 ** | −0.175 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.104 | 0.755 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.7. | PC | −0.284 ** | −0.186 ** | −0.216 ** | −0.165 ** | −0.085 * | 0.219 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.164 ** | −0.052 | −0.161 ** | 0.766 ** | −0.304 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.216 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.8. | PC | −0.237 ** | −0.214 ** | −0.256 ** | −0.134 ** | −0.070 | 0.273 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.204 ** | −0.197 ** | −0.242 ** | 0.779 ** | −0.298 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.099 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.9. | PC | −0.265 ** | −0.191 ** | −0.248 ** | −0.217 ** | −0.076 | 0.221 ** | 0.643 ** | 0.188 ** | −0.129 ** | −0.226 ** | 0.842 ** | −0.315 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.071 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.10. | PC | −0.230 ** | −0.101 * | −0.153 ** | −0.112 ** | −0.022 | 0.201 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.179 ** | −0.144 ** | −0.190 ** | 0.700 ** | −0.206 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.609 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.11. | PC | −0.292 ** | −0.136 ** | −0.211 ** | −0.144 ** | −0.068 | 0.259 ** | 0.592 ** | 0.127 ** | −0.074 | −0.222 ** | 0.803 ** | −0.290 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.108 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.081 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.12_1 | PC | −0.195 ** | −0.127 ** | −0.198 ** | −0.082 | −0.043 | 0.841 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.305 ** | −0.029 | −0.145 ** | 0.241 ** | −0.232 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.307 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.501 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.12_2 | PC | −0.312 ** | −0.183 ** | −0.292 ** | −0.152 ** | −0.069 | 0.439 ** | 0.840 ** | 0.293 ** | −0.113 ** | −0.289 ** | 0.821 ** | −0.342 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.105 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.12_3 | PC | −0.214 ** | −0.204 ** | −0.151 ** | −0.117 ** | −0.085 * | 0.296 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.858 ** | −0.082 | −0.116 ** | 0.176 ** | −0.246 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q13_score | PC | 0.387 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.106 * | 0.214 ** | −0.115 ** | −0.199 ** | −0.124 ** | 0.047 | 0.186 ** | −0.253 ** | 0.375 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.267 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.16. | PC | 0.530 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.127 ** | −0.175 ** | −0.208 ** | −0.125 ** | −0.089 * | 0.061 | −0.250 ** | 0.617 ** |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.149 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| Q1.17. | PC | 0.229 ** | 0.332 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.101 * | −0.205 ** | −0.286 ** | −0.183 ** | −0.003 | 0.113 ** | −0.345 ** | 0.637 ** | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.939 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||

| Q1.18. | PC | 0.616 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.234 ** | −0.139 ** | −0.191 ** | −0.178 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.109 * | −0.202 ** | 0.773 ** | ||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||

| Q1.19. | PC | 0.418 ** | 0.255 ** | −0.188 ** | −0.279 ** | −0.122 ** | 0.228 ** | 0.177 ** | −0.288 ** | 0.817 ** | |||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||

| Q1.20. | PC | 0.153 ** | −0.057 | −0.155 ** | −0.114 ** | 0.123 ** | 0.078 | −0.173 ** | 0.557 ** | ||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.179 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.066 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||

| Q1.24. | PC | −0.025 | −0.065 | −0.122 ** | −0.021 | 0.007 | −0.086 * | 0.263 ** | |||||

| Sig. | 0.554 | 0.124 | 0.004 | 0.618 | 0.861 | 0.041 | 0.000 | ||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||||

| Q1.26_1. | PC | 0.582 ** | 0.382 ** | −0.078 | −0.170 ** | 0.294 ** | −0.226 ** | ||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||||

| Q1.26_2. | PC | 0.391 ** | −0.151 ** | −0.282 ** | 0.753 ** | −0.326 ** | |||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||||||

| Q1.26_3. | PC | −0.117 ** | −0.102 * | 0.218 ** | −0.210 ** | ||||||||

| Sig. | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | 558 | |||||||||

| Q2.3. Age: | PC | 0.136 ** | −0.142 ** | 0.165 ** | |||||||||

| Sig. | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | ||||||||||

| Q2.4. | PC | −0.295 ** | 0.162 ** | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||||

| N | 558 | 558 | |||||||||||

| v1_tata | PC | −0.363 ** | |||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| N | 558 | ||||||||||||

References

- Guze, S. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R.S.; Dickstein, D.P. Anxiety in Adolescents: Update on its Diagnosis and Treatment for Primary Care Providers. Adolescent Health. Med. Ther. 2012, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Runcan, R. Alexithymia in Adolescents: A Review of Literature. Agora Psycho-Pragmatica 2020, 14, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, D.-T.; Dughi, T.; Roman, A.; Ignat, S. Perspectives of Consent Silence in Cyberbullying. Postmod. Open. 2019, 10, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runcan, P. Depression in Adolescence: A Review of Literature. Rev. Asistenţă Soc. 2020, 2, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Runcan, R. Adolescent Substance Use, Misuse, and Abuse. Agora Psycho-Pragmatica 2020, 14, 136–157. [Google Scholar]

- Runcan, R.; Nadolu, B. Social Conditioning for the Self-Harm Behaviour in Adolescence. Agora Psycho-Pragmatica 2020, 14, 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- Runcan, R.; Runcan, P.L.; Goian, C.; Nadolu, B.; Gavrilă-Ardelean, M. Self-harm in Adolescence. In Proceedings of the NORDSCI International Conference, Sociology and Health Care; Saima Consult Ltd.: Sofia, Bulgaria; 2020; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, R. Suicide in Adolescence: A Review of Literature. Rev. Asistenţă Soc. 2020, 3, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, F.W.; Joas, J.; Gerstner, I.; Kühn, A.; Wenning, M.; Gehrke, T.; Burckhart, H.; Richter, U.; Nonnenmacher, A.; Zemlin, M.; et al. Problematic Internet Use among Adolescents 18 Months after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2022, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fors, P.Q.; Barch, D.M. Differential Relationships of Child Anxiety and Depression to Child Report and Parent Report of Electronic Media Use. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2019, 50, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Salman, Z.H.; Al Debel, F.A.; Al Zakaria, F.M.; Shafey, M.M.; Darwish, M.A. Anxiety and depression and their relation to the use of electronic devices among secondary school students in Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia, 2018–2019. J. Fam. Community Med. 2020, 27, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, R.; Drușcă, O. Social Work and Family Relationships: Impact of Paternal Education on Teenage Girls. Rev. De Asistenţă Soc. 2019, 17, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, D.M. Anxiety in Adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Health Psychology; Donohue, W.O., Benuto, L., Tolle, L.W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 507–519. [Google Scholar]

- Weems, C.F.; Silverman, W.K. Anxiety disorders. In Child and Adolescent Psychopathology; Beauchaine, T.P., Hinshaw, S.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 513–541. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsdotter, S. Anxiety among Adolescents: Measurement, Clinical Characteristics, and Influences of Parenting and Genetics. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala Universitet, Uppsala, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M. Parent attitudes and submissive behaviors in adolescents as social anxiety predictors. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 17, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, P.-L. The time factor: Does it influence the parent-child relationship? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 33, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dughi, T. Cultural consumption proposed by parents and cultural consumption chosen by children. Educ. Plus 2010, 6, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nadolu, D.; Runcan, R.; Bahnaru, A. Sociological dimensions of marital satisfaction in Romania. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosim, I.; Runcan, P.; Runcan, R.; Jomiru, C.; Gavrila-Ardelean, M. The Impact of Parental External Labour Migration on the Social Sustainability of the Next Generation in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadolu, B.; Nadolu, D. Homo Interneticus—The Sociological Reality of Mobile Online Being. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. In On the Horizon; MCB University Press: Bingley, UK, 2001; Volume 9, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Selfhout, M.H.; Branje, S.J.; Delsing, M.; Ter Bogt, T.F.; Meeus, W.H. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: The role of perceived friendship quality. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostovar, S.; Allahyar, N.; Aminpoor, H.; Moafian, F.; Nor, M.B.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Internet Addiction and its Psychosocial Risks (Depression, Anxiety, Stress and Loneliness) among Iranian Adolescents and Young Adults: A Structural Equation Model in a Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2016, 14, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, R. Anxiety in Adolescence: A Review of Literature. In Innovative Instruments for Community Development in Communication and Education; Micle, M., Clitan, G., Eds.; Trivent: Budapest, Hungary, 2020; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, R. Facebookmania—The Psychical Addiction to Facebook and Its Incidence on the Z Generation. Rev. Asistenţă Soc. 2015, 14, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Runcan, R. Teenage Vulnerability: Social Media Addiction, In Vulnerabilities in Social Assistance; Breaz, A., Ed.; Presa Univer-sitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2021; pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, A. Facebook Use and Negative Behavioral and Mental Health Outcomes: A Literature Review. J. Addict. Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, N.; Brito, E.B.; Fogel, J.; Fagan, D.; Kumar, K.; Verma, R. The Association of Adolescent Facebook Behaviours with Symptoms of Social Anxiety, Generalized Anxiety, and Depression. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iovu, M.-B.; Runcan, R.; Runcan, P.-L.; Andrioni, F. Association between Facebook Use, Depression and Family Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study of Romanian Youth. Iran. J. Public Health 2020, 49, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maras, D.; Flament, M.F.; Murray, M.; Buchholz, A.; Henderson, K.A.; Obeid, N.; Goldfield, G.S. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev. Med. 2015, 73, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.H.; Chin, B.; Park, D.-H.; Ryu, S.-H.; Yu, J. Characteristics of Excessive Cellular Phone Use in Korean Adolescents. CyberPsychology Behav. 2008, 11, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Child. Media 2008, 2, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Ratliff, E.L.; Cosgrove, K.T.; Steinberg, L. We Know Even More Things: A Decade Review of Parenting Research. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 870–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, M.; McGilloway, S.; Bywater, T.; Hutchings, J.; Smith, S.M.; Donnelly, M. Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 8, CD008225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copăceanu, M.; Costache, I. Policy Brief Child and Adolescent Mental Health in Romania. Unicef. 2022. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/romania/media/10046/file/Child%20and%20Adolescent%20Mental%20Health%20in%20Romania.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Brown, J.; Thompson, L.A.; Trafimow, D. The Father-Daughter Relationship Rating Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2002, 90, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Gollust, S.E.; Golberstein, E.; Hefner, J.L. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2007, 77, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbo, C.; Kinyanda, E.; Kizza, R.B.; Levin, J.; Ndyanabangi, S.; Stein, D.J. Prevalence, comorbidity and predictors of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents in rural north-eastern Uganda. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, N.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S.; Bradley, R.H.; Hofferth, S.; Lamb, M.E. Fatherhood in the Twenty-First Century. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costin, A.; Roman, A.F. Discussing with the Parents of High School Students: What do They Know about Drugs? Postmod. Open. 2020, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, M.P.; Cappella, E.; O’Connor, E.E.; McClowry, S.G. Parent Involvement, Emotional Support, and Behavior Problems. Elem. Sch. J. 2013, 114, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, A.; Rad, D.; Egerau, A.; Dixon, D.; Dughi, T.; Kelemen, G.; Balas, E.; Rad, G. Physical Self-Schema Acceptance and Perceived Severity of Online Aggressiveness in Cyberbullying Incidents. J. Interdiscip. Stud. Educ. 2020, 9, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, R. Conflict Solution in Cyberbullying. Rev. Asistenţă Soc. 2020, 2, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, L.A.; Brown, T.A. Psychometric Properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) in Outpatients with Anxiety and Mood Disorders. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2016, 39, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winquist, N.C.; Brimhall, D.; West, J. Fathers’ Involvement in Their Children’s Schools; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Marici, M. Psycho-Behavioral Consequences of Parenting Variables in Adolescents. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 187, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | Male | Female | ||||||||

| 31.9 | 68.1 | |||||||||

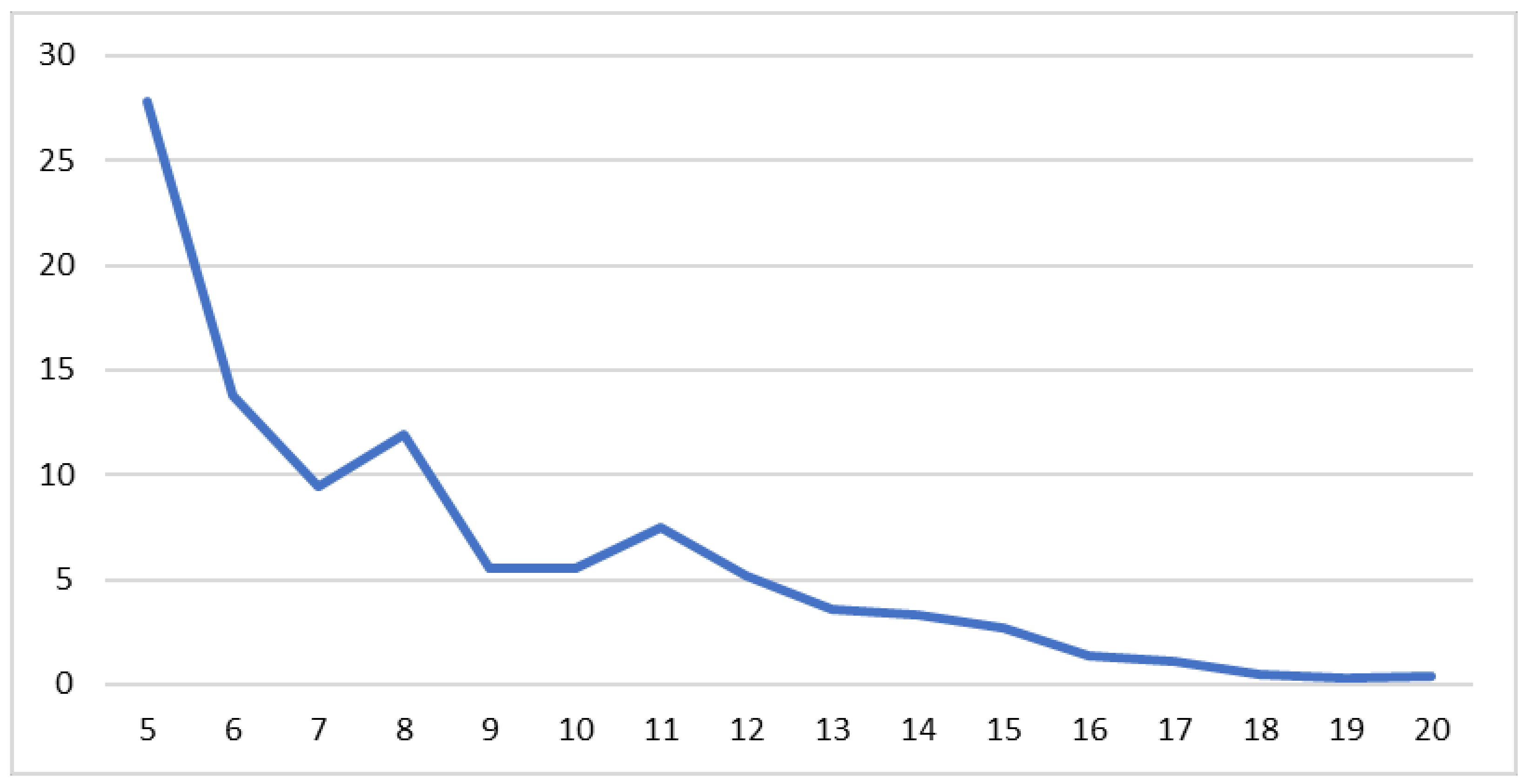

| Age | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | |

| (mean = 17.6 years) | 4.3 | 7.5 | 15.8 | 24.7 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 9.9 | 10 | 11.3 | |

| Residence | Urban | Rural | ||||||||

| 64% | 36% | |||||||||

| Material status | Very good | Good/comfortable | With certain shortcomings | Very bad | ||||||

| 27.8 | 61.5 | 9.7 | 1.1 | |||||||

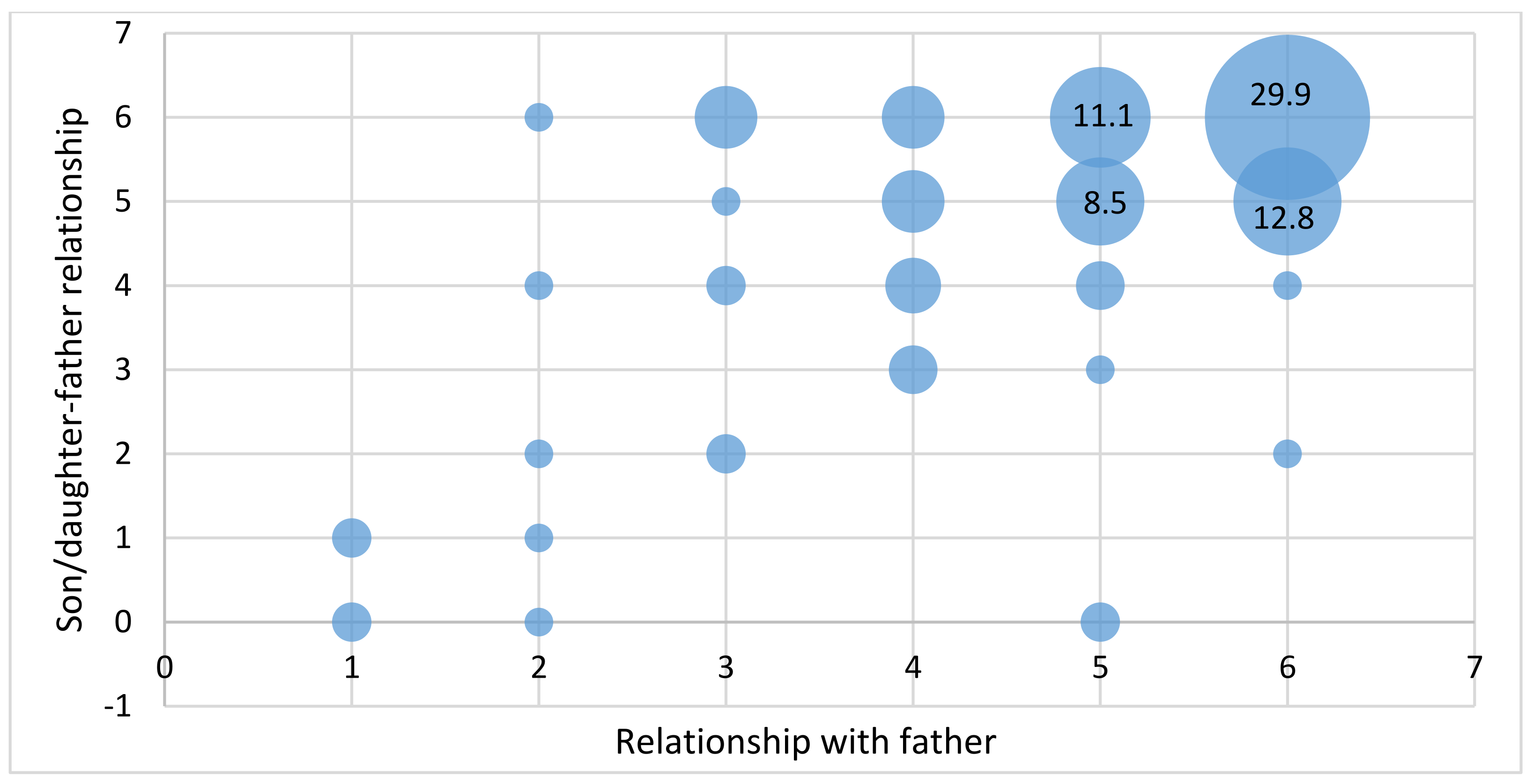

| Communication with Mother | Communication with Father | Communication with Siblings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| v1_father | Pearson Correlation | 0.241 ** | 0.821 ** | 0.176 ** |

| sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

| 0 = Not at All | 1 = Several Days | 2 = More Than Half the Days | 3 = Nearly Every Day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge | 25.5 | 35 | 17.1 | 22.3 |

| 2. Not being able to stop or control worrying | 40.9 | 32.3 | 16.7 | 10.1 |

| 3. Worrying too much about different things | 32.6 | 26.4 | 19 | 22.1 |

| 4. Trouble relaxing | 46.3 | 23.4 | 15.8 | 14.5 |

| 5. Being so restless that it is hard to sit still | 51.5 | 26.5 | 11.8 | 10.2 |

| 6. Becoming easily annoyed or irritable | 26.1 | 32.4 | 22 | 19.4 |

| 7. Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen | 48.4 | 25.2 | 12.2 | 14.2 |

| Level of Anxiety Severity GAD-7 Scale Score | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 0–5—minimal | 233 | 41.7 |

| 6–10—mild | 154 | 27.6 |

| 11–15—moderate | 108 | 19.4 |

| 15–21—severe | 63 | 11.2 |

| Total | 558 | 100.0 |

| v1_Father | v2_Risk | Time Spent on Social Media | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score | Pearson Correlation | −0.253 ** | 0.375 ** | 0.214 ** |

| sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 558 | 558 | 558 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Runcan, R.; Nadolu, D.; David, G. Predictors of Anxiety in Romanian Generation Z Teenagers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064857

Runcan R, Nadolu D, David G. Predictors of Anxiety in Romanian Generation Z Teenagers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064857

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuncan, Remus, Delia Nadolu, and Gheorghe David. 2023. "Predictors of Anxiety in Romanian Generation Z Teenagers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064857

APA StyleRuncan, R., Nadolu, D., & David, G. (2023). Predictors of Anxiety in Romanian Generation Z Teenagers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064857