Five-Factor Personality Dimensions Mediated the Relationship between Parents’ Parenting Style Differences and Mental Health among Medical University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and Design

2.2. Interview Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Mental Health

2.3.2. Five-Factor Personality

2.3.3. Parental Parenting Style Differences (PD)

2.3.4. Social–Demographic Variables

2.3.5. Physical Disease

2.3.6. Parental Relationship and Education Level

2.4. Statistical Analyses

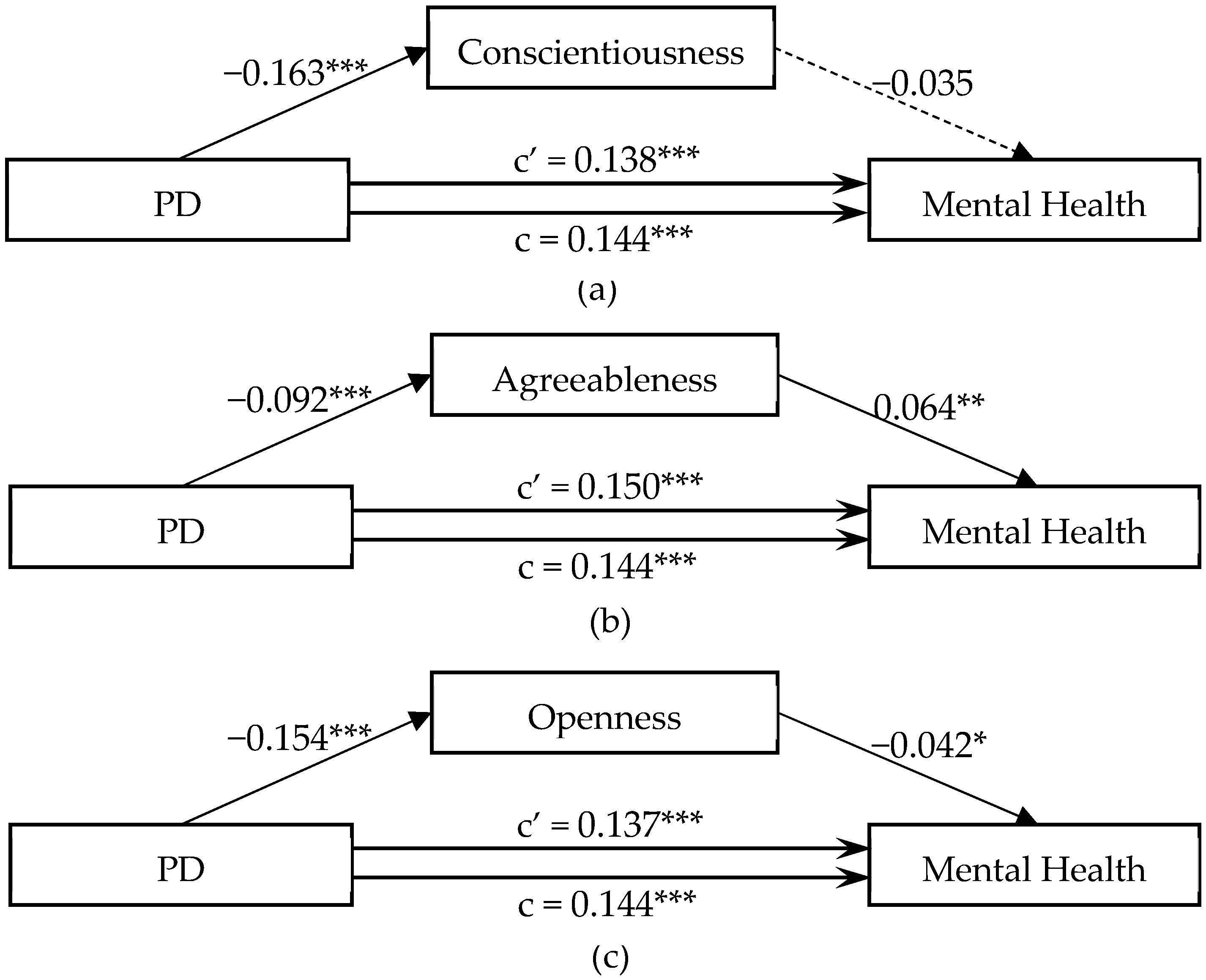

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neel, M.L.M.; Stark, A.R.; Maitre, N.L. Parenting style impacts cognitive and behavioural outcomes of former preterm infants: A systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Rahman, M.N.A. Relationships between parenting style and sibling conflicts: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 936253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuba, A.L.; Meyer, A.H.; Kakebeeke, T.H.; Stulb, K.; Arhab, A.; Zysset, A.E.; Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Schmutz, E.A.; Kriemler, S.; Jenni, O.G.; et al. The relationship of parenting style and eating behavior in preschool children. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshani, T.; Hamid, S.; Kamyab, A.; Kashfi, S.M.; Khani Jeihooni, A. The effect of parenting style on anxiety and depression in adolescent girls aged 12-16 years. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Sun, X.; Huang, Z. Correlation between Parenting Style by Personality Traits and Mental Health of College Students. Occup. Ther. Int. 2022, 2022, 6990151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, F.A.; Yudiana, W.; Fadilah, S.H. Parenting Style and Emotional Well-Being Among Adolescents: The Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Frustration. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 901646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaygan, M.; Bostanian, P.; Zarmehr, M.; Hassanipour, H.; Mollaie, M. Understanding the relationship between parenting style and chronic pain in adolescents: A structural equation modelling approach. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, A.Z.H. Examining the Moderating Effect of Parenting Style and Parental Guidance on Children’s Beliefs about Food: A Test of the Parenting Style-as-Context Model. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Malik, A.S.; Sang, G.; Rizwan, M.; Mushtaque, I.; Naveed, S. Examine the parenting style effect on the academic achievement orientation of secondary school students: The moderating role of digital literacy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1063682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanjarani, F.; Aghaei, K.; Fazaeli, T.; Vaezi, A.; Szczygiel, M. A Structural Equation Modeling of the Relationships Between Parenting Styles, Students’ Personality Traits, and Students’ Achievement Goal Orientation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 805308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, S.; Ayoubi, S.; Brand, S. Parenting Styles Predict Future-Oriented Cognition in Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2022, 9, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, J.; Zheng, L.; Song, W.; Yi, L. Impact of Home Parenting Environment on Cognitive and Psychomotor Development in Children under 5 Years Old: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 658094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M.; Shirotsuki, K.; Sugaya, N. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for management of mental health and stress-related disorders: Recent advances in techniques and technologies. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2021, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, V.; Fagermo, K.; Handegard, B.H.; Skre, I.; Neumer, S.P. A randomized controlled trial of a six-session cognitive behavioral treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents 14–17 years old in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Xu, L.; Sun, L. Association between Parental Parenting Style Disparities and Mental Health: An Evidence from Chinese Medical College Students. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 841140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Z.; Ren, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; Sun, L. Parents parenting styles differences were associated with lifetime suicidal ideation: Evidences from the Chinese medical college students. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 2420–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barańczuk, U. The five factor model of personality and emotion regulation: A meta-analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 139, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J. Pers. 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Personality Trait Structure as a Human Universal. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R. Psychological Testing: History, Principles, and Applications, 6th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.A.; Coyne, S.M.; Swanson, S.M.; Hart, C.H.; Olsen, J.A. Parenting, relational aggression, and borderline personality features: Associations over time in a Russian longitudinal sample. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabbe, E.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Brenning, K.; De Pauw, S.; Beyers, W.; Soenens, B. The moderating role of adolescent personality in associations between psychologically controlling parenting and problem behaviors: A longitudinal examination at the level of within-person change. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berle, D.; Starcevic, V.; Milicevic, D.; Moses, K.; Hannan, A.; Sammut, P.; Brakoulias, V. The factor structure of the Kessler-10 questionnaire in a treatment-seeking sample. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spies, G.; Stein, D.J.; Roos, A.; Faure, S.C.; Mostert, J.; Seedat, S.; Vythilingum, B. Validity of the Kessler 10 (K-10) in detecting DSM-IV defined mood and anxiety disorders among pregnant women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2009, 12, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kessler, R.C.; Slade, T.; Andrews, G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hides, L.; Lubman, D.I.; Devlin, H.; Cotton, S.; Aitken, C.; Gibbie, T.; Hellard, M. Reliability and validity of the Kessler 10 and Patient Health Questionnaire among injecting drug users. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2007, 41, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.N.; Islam, F.M.A.; Al Mahmud, A. Psychometric evaluation of an interview-administered version of the Kessler 10-item questionnaire (K10) for measuring psychological distress in rural Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.M.; Sunderland, M.; Andrews, G.; Titov, N.; Dear, B.F.; Sachdev, P.S. The 10-item Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) as a screening instrument in older individuals. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, X.Q.; You, L.M.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Zheng, J.; Yan, T.B.; Chen, S.X.; Zhang, L.F. Psychometric Properties of the Kessler 10 Scale in Chinese Parents of Children with Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 40, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Chu, J.; Wang, T.; Peng, Q.; He, J.; Zheng, W.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Ma, H.; Xu, L. Reliability and Validity of 10-item Kessler Scale (K10) Chinese Version in Evaluation of Mental Health Status of Chinese Population. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 16, 627–629. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; DAI, X.; Yao, S. Development of the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory(CBF-PI) Ⅲ:Psychometric Properties of CBF-PI Brief Version. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 19, 454–457. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P. NEO Inventories for the NEO Personality Inventory-3 (NEO-PI-3), NEO Five-Factor Inventory-3 (NEO-FFI-3), NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO-PI-R): Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Cai, H.M.; Yang, W.T.; Li, W.P.; Song, B.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.H.; Zhang, H.Z. Effect of personality traits on rehabilitation effect after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: An observational study. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 65, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, B.; Liu, X.; Yin, M.; Humphris, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q. How physicians respond to negative emotions in high-risk preoperative conversations. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Huang, Q.; Huang, S.; Tan, L.; Shao, T.; Fang, T.; Chen, X.; Lin, S.; Qi, J.; Cai, Y.; et al. Prevalence of Internet Gaming Disorder and Its Association With Personality Traits and Gaming Characteristics Among Chinese Adolescent Gamers. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 598585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrindell, W.A.; Richter, J.; Eisemann, M.; Garling, T.; Ryden, O.; Hansson, S.B.; Kasielke, E.; Frindte, W.; Gillholm, R.; Gustafsson, M. The short-EMBU in East-Germany and Sweden: A cross-national factorial validity extension. Scand. J. Psychol. 2001, 42, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, S.L.; Conlon, E.G.; Waters, A.M.; Farrell, L.J. Perceived Parental Rearing in Paediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Examining the Factor Structure of the EMBU Child and Parent Versions and Associations with OCD Symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020, 51, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segnini, A.; Posadas, A.; da Silva, W.T.L.; Milori, D.; Gavilan, C.; Claessens, L.; Quiroz, R. Quantifying soil carbon stocks and humification through spectroscopic methods: A scoping assessment in EMBU-Kenya. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 64, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, F.D.; Atherton, O.E.; DeYoung, C.G.; Krueger, R.F.; Robins, R.W. Big five personality traits and common mental disorders within a hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology: A longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2020, 129, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atari, M.; Yaghoubirad, M. The Big Five personality dimensions and mental health: The mediating role of alexithymia. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2016, 24, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger-Konig, J.; Hertel, J.; Terock, J.; Volzke, H.; Van der Auwera, S.; Grabe, H.J. Predicting physical and mental health symptoms: Additive and interactive effects of difficulty identifying feelings, neuroticism and extraversion. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 115, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahithya, B.R.; Raman, V. Parenting Style, Parental Personality, and Child Temperament in Children with Anxiety Disorders-A Clinical Study from India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, K.; Suzuki, A.; Oshino, S.; Ishii, G.; Matsumoto, Y. Effects of the “affectionless control” parenting style on personality traits in healthy subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 165, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draycott, S.; Dabbs, A. Cognitive dissonance 1: An overview of the literature and its integration into theory and practice in clinical psychology. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 37, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Sanches, M. Parenting Role in the Development of Borderline Personality Disorder. Psychopathology 2023, 56, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Hou, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Shi, C. Neuroticism Trait and Mental Health among Chinese Firefighters: The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support and the Mediating Role of Burnout-A Path Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 870772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Baranova, A.; Zhou, C.; Cao, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M. Causal influences of neuroticism on mental health and cardiovascular disease. Hum. Genet. 2021, 140, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Roy, K.; Wilhelm, K.; Mitchell, P.; Austin, M.-P.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. An exploration of links between early parenting experiences and personality disorder type and disordered personality functioning. J. Personal. Disord. 2011, 13, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stravynski, A.; Elie, R.; Franche, R.L. Perception of early parenting by patients diagnosed avoidant personality disorder: A test of the overprotection hypothesis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1989, 80, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghuis, J.; Bleidorn, W.; Sijtsma, K.; Branje, S.; Meeus, W.H.J.; Denissen, J.J.A. Longitudinal associations between trait neuroticism and negative daily experiences in adolescence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.S.; Hays-Grudo, J. Protective and compensatory childhood experiences and their impact on adult mental health. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhou, C. Self-reported sleep quality and mental health mediate the relationship between chronic diseases and suicidal ideation among Chinese medical students. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L. Associations between Suicidal Ideation and Relatives’ Physical and Mental Health among Community Residents: Differences between Family Members and Lineal Consanguinity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limura, S.; Taku, K. Gender Differences in Relationship Between Resilience and Big Five Personality Traits in Japanese Adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 2018, 121, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.; McCrae, R.R.; De Fruyt, F.; Jussim, L.; Lockenhoff, C.E.; De Bolle, M.; Costa, P.T.; Sutin, A.R.; Realo, A.; Allik, J.; et al. Stereotypes of age differences in personality traits: Universal and accurate? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, K.; Takaishi, J.; Tatsuta, K.; Katayama, H.; Iwase, M.; Yorifuji, K.; Takeda, M. The influences of family environment on personality traits. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000, 54, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean ± SD/n (%) | Mental Health (Mean ± SD) | t/r/F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2583 (100.0) | 19.14 ± 6.65 | -- |

| Gender | t = 0.961 | ||

| Male | 1151 (44.6) | 19.28 ± 6.98 | |

| Female | 1432 (55.4) | 19.03 ± 6.37 | |

| Age | 20.22 ± 1.27 | 19.14 ± 6.65 | r = 0.104 *** |

| Ethnicity | t = −2.116 * | ||

| Hans | 2504 (95.9) | 19.09 ± 6.61 | |

| Others | 79 (3.1) | 20.70 ± 7.69 | |

| Physical disease | t = 6.034 *** | ||

| Yes | 113 (4.4) | 22.81 ± 7.06 | |

| No | 2470 (95.6) | 18.97 ± 6.58 | |

| Economic status | F = 11.829 *** | ||

| Good | 520 (20.1) | 18.18 ± 6.81 | |

| Average | 1786 (69.1) | 19.20 ± 6.54 | |

| Bad | 277 (10.7) | 20.56 ± 6.78 | |

| Only child | t = −1.270 | ||

| Yes | 1190 (46.1) | 18.96 ± 6.88 | |

| No | 1393 (53.9) | 19.29 ± 6.44 | |

| Parental relationship | F = 18.167 *** | ||

| Good | 2170 (84.0) | 18.80 ± 6.51 | |

| Normal | 336 (13.0) | 20.79 ± 6.83 | |

| Bad | 77 (3.0) | 21.48 ± 8.10 | |

| Father’s education | F = 2.238 | ||

| Junior high school or below | 1312 (50.8) | 19.41 ± 6.32 | |

| Junior college/senior school | 887 (34.3) | 18.85 ± 6.86 | |

| Bachelor degree or above | 384 (14.9) | 18.88 ± 7.20 | |

| Mother’s education | F = 2.171 | ||

| Junior high school or below | 1562 (60.5) | 19.33 ± 6.52 | |

| Junior college/senior school | 720 (27.9) | 18.98 ± 6.70 | |

| Bachelor degree or above | 301 (11.7) | 18.52 ± 7.14 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Big five personality dimensions | |||||||

| 1.1 Neuroticism | 23.65 ± 6.41 | 1 | |||||

| 1.2 Conscientiousness | 29.28 ± 6.85 | 0.308 *** | 1 | ||||

| 1.3 Agreeableness | 28.09 ± 5.80 | 0.444 *** | 0.668 *** | 1 | |||

| 1.4 Openness | 30.10 ± 7.47 | 0.261 *** | 0.706 *** | 0.648 *** | 1 | ||

| 1.5 Extraversion | 27.63 ± 6.11 | 0.368 *** | 0.679 *** | 0.627 *** | 0.763 *** | 1 | |

| 2. Mental health | 19.14 ± 6.65 | 0.498 *** | −0.069 *** | 0.027 | −0.079 *** | 0.002 | 1 |

| 3. PD | 4.33 ± 5.97 | 0.013 | −0.160 *** | −0.116 *** | −0.134 *** | −0.090 *** | 0.146 *** |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 2583 | 2583 |

| Male | 0.31 (−0.22, 0.84) | 0.73 (0.29, 1.18) ** |

| Age | 0.48 (0.29, 0.68) *** | 0.45 (0.28, 0.62) *** |

| Hans ethnicity | −1.49 (−2.94, −0.03) * | −1.08 (−2.30, 0.14) |

| Physical disease | 3.37 (2.14, 4.60) *** | 2.34 (1.30, 3.37) *** |

| Economic status (Ref. = Average) | ||

| Good | −0.96 (−1.63, −0.29) ** | −0.56 (−1.12, 0.01) |

| Bad | 0.42 (−0.43, 1.27) | 0.10 (−0.62, 0.81) |

| Only child | −0.46 (−1.03, 0.10) | −0.42 (−0.89, 0.05) |

| Parental relationship (Ref. = Normal) | ||

| Good | −1.38 (−2.14, −0.61) *** | −0.73 (−1.37, −0.08) * |

| Bad | 0.30 (−1.32, 1.91) | −0.47 (−1.83, 0.89) |

| Father’s education (Ref. = Junior high school or below) | ||

| Junior college/senior school | −0.23 (−0.86, 0.40) | −0.07 (−0.60, 0.46) |

| Bachelor degree or above | 0.32 (−0.72, 1.36) | 0.51 (−0.36, 1.38) |

| Mother’s education (Ref. = Junior high school or below) | ||

| Junior college/senior school | 0.15 (−0.53, 0.82) | 0.26 (−0.31, 0.83) |

| Bachelor degree or above | −0.39 (−1.51, 0.73) | −0.38 (−1.32, 0.55) |

| PD | 0.15 (0.10, 0.19) *** | 0.10 (0.06, 0.14) *** |

| Neuroticism | -- | 0.61 (0.57, 0.65) *** |

| Conscientiousness | -- | −0.11 (−0.16, −0.06) *** |

| Agreeableness | -- | −0.10 (−0.15, −0.04) ** |

| Openness | -- | −0.05 (−0.10, −0.002) * |

| Extraversion | -- | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.04) |

| Constant | 11.41 (7.08, 15.75) *** | 4.78 (0.90, 8.66) * |

| R2 | 0.060 | 0.343 |

| Neuroticism | Conscientiousness | Agreeableness | Openness | Extraversion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2583 | 2583 | 2583 | 2583 | 2583 |

| Male | −1.15 (−1.67, −0.63) *** | −0.85 (−1.40, −0.30) ** | −1.34 (−1.80, −0.88) *** | −0.80 (−1.40, −0.20) ** | −0.69 (−1.19, −0.20) ** |

| Age | −0.06 (−0.26, 0.13) | −0.15 (−0.36, 0.06) | −0.28 (−0.45, −0.10) ** | −0.45 (−0.68, −0.23) *** | −0.29 (−0.47, −0.10) ** |

| Hans ethnicity | −0.28 (−1.71, 1.16) | 1.08 (−0.43, 2.60) | 0.87 (−0.42, 2.15) | 0.62 (−1.04, 2.28) | 0.11 (−1.25, 1.48) |

| Physical disease | 1.57 (0.37, 2.78) ** | −0.47 (−1.75, 0.80) | −0.62 (−1.70, 0.46) | 0.68 (−0.71, 2.08) | 0.11 (−1.04, 1.26) |

| Economic status (Ref. = Average) | |||||

| Good | −1.09 (−1.75, −0.43) ** | −0.92 (−1.61, −0.22) ** | −1.19 (−1.78, −0.60) *** | −0.69 (−1.45, 0.07) | −0.38 (−1.01, 0.25) |

| Bad | 0.26 (−0.58, 1.09) | −0.78 (−1.67, 0.10) | −0.40 (−1.15, 0.35) | −0.56 (−1.53, 0.41) | −0.48 (−1.28, 0.32) |

| Only child | −0.22 (−0.78, 0.33) | −0.62 (−1.21, −0.03) * | −0.23 (−0.73, 0.27) | −0.03 (−0.67, 0.61) | −0.08 (−0.61, 0.45) |

| Parental relationship (Ref. = Normal) | |||||

| Good | −0.53 (−1.28, 0.22) | 1.60 (0.80, 2.39) *** | 0.80 (0.12, 1.47) * | 0.99 (0.12, 1.87) * | 0.98 (0.26, 1.70) ** |

| Bad | 1.60 (0.01, 3.19) * | 1.41 (−0.27, 3.09) | 0.51 (−0.91, 1.94) | −0.09 (−1.92, 1.75) | 0.44 (−1.08, 1.95) |

| Father’s education (Ref. = Junior high school or below) | |||||

| Junior college/senior school | −0.16 (−0.79, 0.46) | 0.24 (−0.42, 0.89) | 0.02 (−0.53, 0.58) | 0.61 (−0.11, 1.33) | 0.18 (−0.42, 0.77) |

| Bachelor degree or above | −0.28 (−1.30, 0.75) | 0.04 (−1.04, 1.12) | 0.05 (−0.86, 0.97) | 0.25 (−0.93, 1.43) | −0.05 (−1.02, 0.92) |

| Mother’s education (Ref. = Junior high school or below) | |||||

| Junior college/senior school | −0.04 (−0.70, 0.63) | 0.29 (−0.42, 0.99) | 0.11 (−0.49, 0.71) | 0.69 (−0.09, 1.46) | 0.62 (−0.02, 1.25) |

| Bachelor degree or above | 0.20 (−0.90, 1.29) | 0.56 (−0.60, 1.72) | 0.06 (−0.93, 1.04) | 0.96 (−0.31, 2.22) | 0.54 (−0.51, 1.59) |

| PD | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.06) | −0.15 (−0.20, −0.11) *** | −0.09 (−0.12, −0.05) *** | −0.15 (−0.20, −0.10) *** | −0.08 (−0.12, −0.04) *** |

| Constant | 26.32 (22.06, 30.58) *** | 31.22 (26.72, 35.73) *** | 33.51 (29.69, 37.32) *** | 38.49 (33.57, 43.42) *** | 32.96 (28.90, 37.02) *** |

| R2 | 0.025 | 0.044 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, S.; Xu, M.; Sun, L. Five-Factor Personality Dimensions Mediated the Relationship between Parents’ Parenting Style Differences and Mental Health among Medical University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4908. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064908

Yao S, Xu M, Sun L. Five-Factor Personality Dimensions Mediated the Relationship between Parents’ Parenting Style Differences and Mental Health among Medical University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4908. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064908

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Shuxin, Meixia Xu, and Long Sun. 2023. "Five-Factor Personality Dimensions Mediated the Relationship between Parents’ Parenting Style Differences and Mental Health among Medical University Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4908. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064908

APA StyleYao, S., Xu, M., & Sun, L. (2023). Five-Factor Personality Dimensions Mediated the Relationship between Parents’ Parenting Style Differences and Mental Health among Medical University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4908. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064908