Doctors’ Professional and Personal Reflections: A Qualitative Exploration of Physicians’ Views and Coping during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design, Participant Recruitment, and Data Collection

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

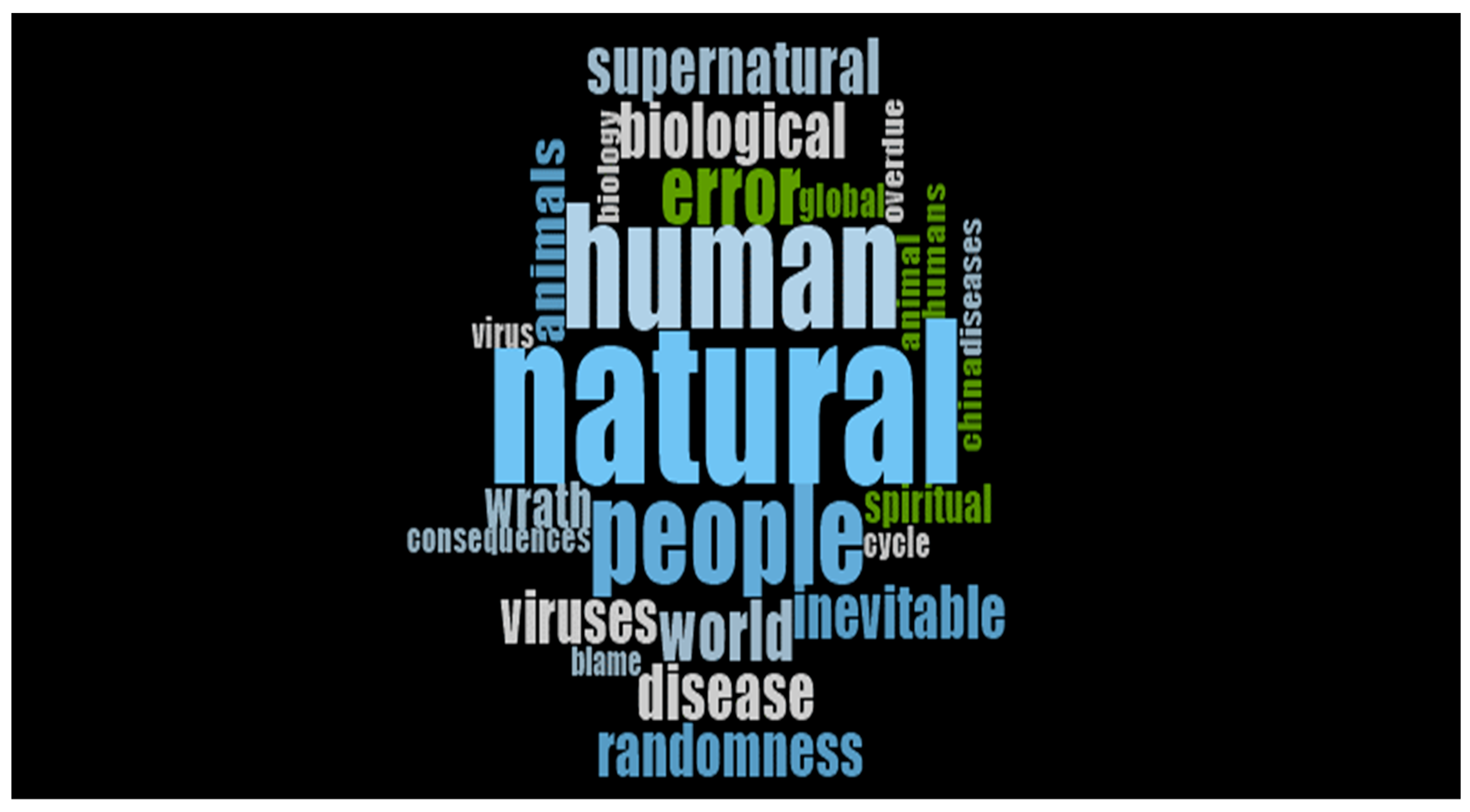

3.1. Physician’s View of the Pandemic’s Origin

3.1.1. Natural Occurrence

3.1.2. Human Error

3.1.3. Religious/Spiritual

3.2. The Effects of the Pandemic on Physicians’ Experiences

3.2.1. Facing Mortality and Developing Appreciation

3.2.2. Physicians Acknowledge Their Vulnerability

3.2.3. Discovering Strengths

3.2.4. Mixed Feelings about Virtual Care

3.3. Physicians’ Emotional Experiences Related to the Pandemic

3.3.1. Empathy and Concern for Others

3.3.2. Anger and Frustration

3.3.3. Guilt

3.3.4. Injustice and Betrayal

3.3.5. Anxiety and Fear

3.3.6. Gratitude

3.3.7. Pride

3.3.8. Togetherness

3.4. Physicians’ Coping

3.4.1. Knowledge

3.4.2. Problem Solving

3.4.3. Relationships

3.4.4. Religion and Spirituality

3.4.5. Behavioral Coping

3.5. Lessons Learned and Their Implications

3.6. Lessons to Be Learned

3.6.1. Acknowledging Realities and Acting

3.6.2. Strengths and Limitations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Contribution to Knowledge

6.1. What Does This Study Add to Existing Knowledge?

6.2. What Are the Key Implications for Public Health Interventions, Practice, or Policy?

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, J.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, F.; Ma, R.; Yang, X. Optimizing Quality of Life among Chinese Physicians: The Positive Effects of Resilience and Recovery Experience. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.M.F. Beyond Burnout: Looking Deeply into Physician Distress. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 55, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.; Bachu, R.; Adikey, A.; Malik, M.; Shah, M. Factors Related to Physician Burnout and Its Consequences: A Review. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Graham, M.S.; Joshi, A.D.; Guo, C.-G.; Ma, W.; Mehta, R.S.; Warner, E.T.; Sikavi, D.R.; Lo, C.-H.; et al. Risk of COVID-19 among Front-Line Health-Care Workers and the General Community: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e475–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, B.M.; Cooper, R.J.; Medak, A.J.; Lim, S.; Chinnock, B.; Frazier, R.; Roberts, B.W.; Epel, E.S.; Rodriguez, R.M. Emergency physician stressors, concerns, and behavioral changes during COVID-19: A longitudinal study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2021, 28, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, S.; Oetjen, N.; Du, J.; Posenato, E.; Resende de Almeida, R.M.; Losada, R.; Ribeiro, O.; Frisardi, V.; Hopper, L.; Rashid, A.; et al. Mental Health Among Medical Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Eight European Countries: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.-A.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C.M. A Rapid Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers: Implications for Supporting Psychological Well-Being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myran, D.T.; Cantor, N.; Rhodes, E.; Pugliese, M.; Hensel, J.; Taljaard, M.; Talarico, R.; Garg, A.X.; McArthur, E.; Liu, C.-W.; et al. Physician Health Care Visits for Mental Health and Substance Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2143160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gindi, H.; Shalaby, R.; Gusnowski, A.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Hrabok, M.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Agyapong, V. Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic among Physicians, Nurses, and Other Healthcare Providers, in the Province of Alberta (Preprint). JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, 27469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, M.; Chimowitz, H.; Nanavati, J.D.; Huff, N.R.; Isbell, L.M. A Qualitative Investigation of the Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) on Emergency Physicians’ Emotional Experiences and Coping Strategies. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2021, 2, e12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.F.; Parvin, M.F.; Rashid, M.M.-U.; Alam, M.S.; Kamrunnahar, M.; Talukder, A.; Rahman Razu, S.; Ward, P.R.; Ali, M. Mental Health of Physicians during COVID-19 Outbreak in Bangladesh: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 592058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario’s Doctors Report Increased Burnout, Propose Five Solutions. Available online: https://www.oma.org/newsroom/news/2021/aug/ontarios-doctors-report-increased-burnout-propose-five-solutions (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Conti, C.; Fontanesi, L.; Lanzara, R.; Rosa, I.; Doyle, R.L.; Porcelli, P. Burnout Status of Italian Healthcare Workers during the First COVID-19 Pandemic Peak Period. Healthcare 2021, 9, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civantos, A.M.; Byrnes, Y.; Chang, C.; Prasad, A.; Chorath, K.; Poonia, S.K.; Jenks, C.M.; Bur, A.M.; Thakkar, P.; Graboyes, E.M.; et al. Mental Health among Otolaryngology Resident and Attending Physicians during The COVID-19 Pandemic: National Study. Head Neck 2020, 42, 1597–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N.; Asaoka, H.; Kuroda, R.; Tsuno, K.; Imamura, K.; Kawakami, N. Sustained Poor Mental Health among Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Four-Wave Panel Survey over 8 Months in Japan. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons Leigh, J.; Kemp, L.G.; de Grood, C.; Brundin-Mather, R.; Stelfox, H.T.; Ng-Kamstra, J.S.; Fiest, K.M. A Qualitative Study of Physician Perceptions and Experiences of Caring for Critically Ill Patients in the Context of Resource Strain during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Sathyanarayana Rao, T.S.; Kallivayalil, R.A.; Javed, A. Psychosocial Framework of Resilience: Navigating Needs and Adversities during the Pandemic, a Qualitative Exploration in the Indian Frontline Physicians. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 622132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, N.; Ali, D.M.; Razzak, J. Physical and Mental Health Impacts of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, D.; Haase, J.E.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, S.; Xia, L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, B.X. The Experiences of Health-Care Providers during the COVID-19 Crisis in China: A Qualitative Study. Lancet Global Health 2020, 8, e790–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaucher, N.; Trottier, E.D.; Côté, A.-J.; Ali, H.; Lavoie, B.; Bourque, C.-J.; Ali, S. A Survey of Canadian Emergency Physicians’ Experiences and Perspectives during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 23, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Psychological Resilience, Coping Behaviours and Social Support among Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.J.; Buttell, F.; Cannon, C. COVID-19: Immediate Predictors of Individual Resilience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.; Wallner, C.; de Wit, K.; Gérin-Lajoie, C.; Ritchie, K.; Mercuri, M.; Clayton, N.; Boulos, M.; Archambault, P.; Schwartz, L.; et al. Humans Not Heroes: Canadian Emergency Physician Experiences during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Med. J. 2022, 40, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, K.A.; Willis, D.G. Descriptive versus Interpretive Phenomenology: Their Contributions to Nursing Knowledge. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. pp. 54–71. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-23864-004 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Gokdemir, O.; Pak, H.; Bakola, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Hoedebecke, K.; Jelastopulu, E. Family Physicians’ Knowledge about and Attitudes towards COVID-19—A Cross-Sectional Multicentric Study. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 52, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakose, T.; Malkoc, N. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Medical Doctors in Turkey. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrabani, S.; Bord, S.; Admi, H.; Halberthal, M. Physicians’ Compliance with COVID-19 Regulations: The Role of Emotions and Trust. Healthcare 2022, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G.; Kendino, M.; Brolan, C.E.; Mitchell, R.; Herron, L.-M.; Kὃrver, S.; Sharma, D.; O’Reilly, G.; Poloniati, P.; Kafoa, B.; et al. Lessons from the Frontline: Leadership and Governance Experiences in the COVID-19 Pandemic Response across the Pacific Region. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 25, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysan, A.; Kayani, F.; Kayani, U.N. The Chinese Inward FDI and Economic Prospects Amid COVID-19 Crisis. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2020, 14, 1088–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Kayani, U.N.; Khan, M.; Mughai, K.S.; Haseeb, M. COVID-19 Pandemic & Financial Market Volatility; Evidence from GARCH Models. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics (N = 17) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 (53) |

| Age: | |

| 25–44 | 5 (29) |

| 45–65 | 10 (59) |

| 66 and over | 2 (12) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 15 (88) |

| Specialty or clinical role | |

| Family Medicine | 5 (28) |

| Pathology | 2 (12) |

| Urology | 1 (6) |

| Pediatrician | 1 (6) |

| Rheumatology | 1 (6) |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 1 (6) |

| Psychiatry | 2 (12) |

| Anesthesiology | 1 (6) |

| Ear Nose and Throat | 1 (6) |

| Infection disease | 1 (6) |

| Neurosurgery | 1 (6) |

| Years in practice | |

| <1 to 5 | 4 (24) |

| 6–10 | 2 (12) |

| 11–15 | 4 (24) |

| 16–20 | 2 (12) |

| >21 | 5 (28) |

| Theme | |

|---|---|

| Subtheme | Participants’ Quotes |

| RENEWED APPRECIATION FOR PERSONAL LIFE | |

| Facing mortality and developing appreciation for the time left Appreciation for family members and togetherness as a family | “In facing mortality, you discover that you want to spend time enjoying life…Just wanting to make time to commit to your interests and hobbies and basically just enjoying life not just working” (P13) “at my age… I can’t afford to ignore some of the other things I would like to be doing. If I want to get a horse and ride, I need to do that I can’t put it off indefinitely” (P13) “I won’t have them forever [parents] …I feel like I am given many chances to get that priority right…it is unfortunate it has taken this [the pandemic]’’ (P12) “So, my wife, kids, her parents, my dad and the immediate family, all of the energy that would have previously gone into socializing, hanging out with people that sort of stuff …the only priority right now is the family” (P7) “Just doing everything as a small family has been very lovely and at the beginning spending every evening with the kids that were home rather than everyone was running around. The usual family game night happening every night rather than once in a while. Eating together, learning to do more things together” (P6) |

| FACING VULNERABILITIES AND DISCOVERING STRENGTHS | |

| Acknowledging one’s vulnerability Discovering new skills Discovering new leaders Discovering resilience Adapting | “I have never dealt with burnout before, and I have been a little bit burnt out during the pandemic. I think it is the lack of being able to recharge in ways that I would normally recharge; that has really affected me and like I have not been able to travel to see my family or visit friends or you know do dinner parties or anything really … It has been humbling. I kind of thought I was immune to burnout, but I am obviously not” (P11) “There will be some moral distress and some baggage that will come out in time. We just need to be cognizant that there will be need for some help down the line” (P8) “So, this has forced all of us to learn a new skill set of how you conduct clinic virtually, be it by phone or be it online. So normally we can see the patient, we can tell they are not in respiratory distress, but you have to learn how to make those inferences through a phone visit, so it is kind of a new skill set that we had to learn” (P7) “It has created some leaders, not myself, but some young doctors I work with, have really been thrust into the leadership positions very early on in their career; so it has really helped foster a lot of personal or a lot of personal growth in those people” (P7) “I realized that we are not...just human beings, we are more resilient than we give ourselves credit for and even though we might have those feelings of guilt, we can adapt, and we can respond in positive ways” (P2) “With the support from the Saskatchewan Medical Association for virtual billing codes and support from our departments and our divisions we were able to adapt” (P2) |

| PERCEPTIONS OF VIRTUAL CARE | |

| Positive views on virtual care Negative views on virtual care | “COVID was the driving force that forced the government to open Pandora’s box and allow us to do virtual care …going forward virtual care is going to make a real difference for patients” (P7) “it is better for physicians, it is better for patients, it is better for access” (P10) “I really did not feel I was getting as full as an assessment…[it] delays care because I had to see all those people in person anyways. They all had to follow up with me in person” (P15) “it was very hard to start a practice when everything is virtual. You sort of miss the random encounters with people that will help you” (P16) |

| Themes and Subthemes | Participants’ Quotes |

|---|---|

| POSITIVE EMOTIONS | |

| Peace and joy | “Um to be honest I think…it was all fun. Peace would be the closest one (emotion). I mean there was a job to do, and I was happy to do it” (P3) |

| Reflection | “It has created time and opportunity for contemplation around defining what is valuable …and then cutting out what is not valuable and then obviously trying to work on things that matter” (P8) |

| Gratitude and appreciation | “I feel very fortunate personally because I am in a situation where I am not losing my job, my income has not changed at all because I am salaried, I have gone through the pandemic and gone through the illness, and it has been very mild… could have been a lot worse” (P15) “I think there are lots of things in life that we at one point maybe just took for granted and now I think we have opportunities to just reflect upon how much joy we can get from simple things in life um and not to take things for granted” (P2) |

| Hope | “I have some hope because I see people working together a little bit more closely now and trying to solve problems that we do have” (P1) |

| Pride | “I feel a lot of pride especially in my colleagues because I think they are very tough, like it has been very hard and I have been so proud of all the people sharing the work with me... they have all stepped up and done the hard work that is necessary” (P4) |

| Togetherness | “It has been really nice to connect with them as friends [and] colleagues; we kind of unofficially socialize at work (laugh)” (P11) “There has been a sense of accomplishment and teamwork and interconnection that I had not previously experienced that has been in some ways a real joy” (P9) “I started doing shifts again and that made me very happy, to actually start doing shifts again and being happy to be back in the trenches with my friends and the other physicians” (P3) “our family has grown closer because we have had to spend more, you know, all of my free time...with my family, I think our family relationships are closer” (P4) “Loving time with my family, that has been really nice and spending time with my kids” (P11) |

| Relief | “Those meetings, I don’t drive so I had to travel through shuttle or taxis to different hospitals to attend the meetings… but now here they are all online on Webex, so that is also a feeling of relief” (P5) |

| MIXED EMOTIONS | “I think this has brought out the best and the worst in people and so whenever I think about the positive it is like I get a yang and right away I am thinking about the negative as well” (P12) |

| NEGATIVE EMOTIONS | |

| Empathy and concern for others | “Being relatively comfortable financially, having a house with good internet access, you look around and you see families in worse situations, and you wonder how they cope” (P6) “I feel like my empathy level has skyrocketed...I find it harder to create that clinical distance. I tear up a lot more at work, and I find it hard to hear somebody’s stories when I am on-call” (P11) |

| Anger, disappointment, and frustration | “It [the pandemic] has affected my wife’s mental and physical health. Seeing how it affected my kids was hard” (P6) “I may be more sensitive to some of the harms of the lockdowns” (P15) “I started to feel very irritated and angry because I felt that [those who] were more removed from clinical care weren’t understanding of the pressures…I felt that people were talking about irrelevant things” (P4) “We have a new area lead, who disappointed me greatly by being authoritarian when it was not necessary to be” (P17) “We are not even on the radar of the Saskatchewan Health Authority in terms of being worthy of a vaccine, so it went from stoicism and just getting the job done, to a little bit of anger, to like really over anger” (P7) |

| Guilt | “I struggle with guilt. About not being present enough for my kids or for my husband. I have to work more so I can’t do as many things as I used do with them, so I deal with a lot of guilt” (P4) |

| Injustice and betrayal | “We are not even remotely on the radar of the Saskatchewan Health Authority in terms of being worthy of a vaccine, so it went from stoicism and just get the job done to a little bit of anger, to like [really] anger.” (P7) |

| Anxiety and fear | “The worst thing is not knowing what is coming, the unknown, a good example would be the COVID variant [B117]; what are the implications of this in terms of the COVID vaccine, what are the implications...for healthcare resources.” (P2) |

| Self-doubt | “My income has reduced, and I am unable to travel…and not going out to meet friends and staying alone in the house is making me sort of question my purpose of life, and what I am doing” (P5) |

| Sadness | “Feeling sad, intimidated, unhappy not wanting to go to the job; but I love my job so much and I am so passionate if somebody asks me to come back during my vacation and do some work and even if they don’t pay me extra, I am very much willing to go, I like my job so much” (P5) |

| Theme and Subthemes | Participants’ Quotes |

|---|---|

| MEDIATORS OF HOPE | |

| Faith in accumulated knowledge | “This too shall pass. This has happened before and there will be a price to be paid…it will be a better state sometime from now” (P8) “Pandemics have a natural cycle to them… of 2–3 years even if we didn’t have a vaccine. So as a scientist I know there is an end to this” (P7) |

| Faith in the ability to find solutions | “Humankind will have learned from this experience and that things will be better next time” (P4) “I believe that as people we do strive to come together in times of crises, and I think we will solve our problem one way or the other” (P1) |

| Faith in relationships | “My parents and my immediate family … phone calls or video calls to stay in touch (those have been helpful in terms of maintaining my own kind of mental wellness). If you express that vulnerability to close people around you, it actually can be quite powerful” (P2) |

| Faith in religion or spirituality | “I read scripture everyday…” (P4) “I spiritually feel this bad period is lasting more than ever like…. but I still feel that this period is not viable, it cannot stay” (P5) |

| Faith in action | “[motivator] to get out and go for runs and walks and bike rides in the summer and in the winter cross country skiing and snowshoeing” (P11) |

| Themes and Subthemes | Participants’ Quotes |

|---|---|

| IMPROVING WORK–LIFE BALANCE | |

| Reducing work hours Renegotiating contracts Redefining boundaries Making room for personal interest | “I was getting lost a bit in how much the job entailed and how many hours I had been working per week, so I need to pull away from that a little bit and give a little more time to myself” (P3) “…probably see if I can negotiate a slight change in my work so that there is more flexibility, or you know I might even go as far as see if there is a way to do a FTE reduction maybe go down to 0.9 or something just for the family side of things. Um but I guess the thing I am looking most forward to is life returning to normal so getting to do all of the things that you had to stop doing” (P7) “I hope that I have better work boundaries and that I [can] turn my phone off when I go home and not just constantly be available for work, I think that will be a big one for me if I could take that away from this” (P11) “I will go down to 60% and then maybe 25% I will just have to gage how long I stay working completely but I have a transition phase going on actively during the pandemic. Personally, it gives me time to gear up in other activities and prepare for having even more time to do those things” (P13) |

| PRIORITIZING TOGHETHERNESS | |

| Making plans to reconnect and socialize Prioritizing time spent with others in personal and professional circumstances | “I will honestly try to spend more time with my colleagues because I miss them…. take my wife to see her family” (P1) “Prioritizing spending time with people will be really high on our list and I think prioritizing um professionally those team building and then really getting those communication lines down especially professionally with our communities” (P14) “I am looking forward to house parties again, like dinner parties, like having people over for dinner…most important thing to do will be to see my family. I miss my parents and my brother, and I want to just go and meet and see them” (P11) |

| REJUVENATING HEALTH CARE | |

| Improving health care system and patient care Preparing for the future Improving continuity of care | “That we have improved our healthcare system. That we take better care of the more vulnerable” (P13) “That we do better pandemic preparation in the future that we build better systems as a result of this” (P13) “Find a better way of managing pandemics but still addressing other critical issues” (P15) “The importance of continuity care centers like having subspecialized care and like the COVID pandemic one of the side effects of it is it has been so having all the COVID stuff to deal with has meant that everything has been put on the back burner” P11 |

| IMPROVING SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY | |

| Improving effort recognition Increasing community awareness Recognizing the importance of science | “The value of minimum wage workers and that minimum wage needs to go up” (P14) “Appreciating a big part of the greater community and we need to look out for each other” (P8) “don’t ignore science, don’t ignore the truth…. evidence matters, feelings aren’t facts...I hope they [people] step away from (hesitates) making decisions that are against [their] own self-interests, like not wearing a mask, like going to a big BBQ” (P10) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adams, G.C.; Reboe-Benjamin, M.; Alaverdashvili, M.; Le, T.; Adams, S. Doctors’ Professional and Personal Reflections: A Qualitative Exploration of Physicians’ Views and Coping during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075259

Adams GC, Reboe-Benjamin M, Alaverdashvili M, Le T, Adams S. Doctors’ Professional and Personal Reflections: A Qualitative Exploration of Physicians’ Views and Coping during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(7):5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075259

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdams, G. Camelia, Monique Reboe-Benjamin, Mariam Alaverdashvili, Thuy Le, and Stephen Adams. 2023. "Doctors’ Professional and Personal Reflections: A Qualitative Exploration of Physicians’ Views and Coping during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 7: 5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075259

APA StyleAdams, G. C., Reboe-Benjamin, M., Alaverdashvili, M., Le, T., & Adams, S. (2023). Doctors’ Professional and Personal Reflections: A Qualitative Exploration of Physicians’ Views and Coping during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075259