Maternal Distress and Adolescent Mental Health in Poor Chinese Single-Mother Families: Filial Responsibilities—Risks or Buffers?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Maternal Distress and Adolescent Mental Health

1.2. Adolescent Filial Responsibility as a Moderator

1.3. Moderation of Adolescent Gender and Age

1.4. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Maternal Distress

2.2.2. Adolescent Mental Health

2.2.3. Adolescent Filial Responsibilities

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. OECD Family Database. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Database 2009–2019. 2020. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/Statisticaldata/AnnualData/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Census and Statistics Department. Marriage and Divorce Trends in Hong Kong, 1991 to 2020; Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Hong Kong, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department. Hong Kong 2016 Population By-Census—Thematic Report: Single Parent; Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, J.; Ridge, T. Relationships of care: Working lone mothers, their children and employment sustainability. J. Soc. Policy 2009, 38, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagel, H.; Hübgen, S. A life-course approach to single mothers’ economic wellbeing in different welfare states. In The Triple Bind of Single-Parent Families; Nieuwenhuis, R., Maldonado, L.C., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2018; pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Chant, S. Gender, Generation and Poverty; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, R.D.; Donnellan, M.B. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, R.D.; Wallace, L.E.; Sun, Y.; Simons, R.L.; McLoyd, V.C.; Brody, G.H. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 38, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L. Poverty and adolescent developmental outcomes: A critical review. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2011, 23, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C. The diversity, strengths, and challenges of single-parent households. In Normal Family Processes: Growing Diversity and Complexity; Walsh, F., Ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 121–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.J.; Zalot, A.A.; Foster, S.E.; Sterrett, E.; Chesterm, C. A review of childrearing in African American single mother families: The relevance of a coparenting framework. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2007, 16, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P.R.; Keith, B. Parental divorce and the wellbeing of children: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J.L.; Chorpita, B.F.; Weisz, J.R. Relation between parent psychiatric symptoms and Youth problems: Moderation through family structure and youth gender. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, E.; Greene, S.; Hogan, D.M. Negotiating relationships in single-mother households: Perspectives of children and mothers. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Zhang, W. Attitudes toward family obligation among adolescents in contemporary urban and rural China. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperminc, G.P.; Wilkins, N.J.; Jurkovic, G.J.; Perilla, J.L. Filial responsibility, perceived fairness, and psychological functioning of Latino youth from immigrant families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2013, 27, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurkovic, G.J.; Thirkield, A.; Morrell, R. Parentification of adult children of divorce: A multidimensional analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2001, 30, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, S.R.; Romero, J. Family responsibilities among Latina college students from immigrant families. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 2008, 7, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.J.; Paley, B. Families as systems. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 45, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minuchin, S.; Montalvo, B.; Guerney, B.; Rosman, B.; Schumer, F. Families of The Slums: An Exploration of Their Structure and Treatment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Flook, L. A social identity approach to ethnic differences in family relationships during adolescence. In Advances in Child Development and Behavior; Kail, R., Ed.; Academic Press: Fletcher, NC, USA, 2005; pp. 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, L.M.; Wallace, S.A.; Doehler, K.; Dantzler, J. Parentification, ethnic identity, and psychological health in Black and White American college students: Implications of family-of-origin and cultural factors. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2012, 43, 811–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boszormenyi-Nagy, I.; Spark, G. Invisible Loyalties: Reciprocity in Intergenerational Family Therapy; Brunner/Mazel: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, N.D. Burdened Children: Theory, Research, and Treatment of Parentification; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, L. Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Fam. Relat. 2007, 56, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.J.; Luthar, S.S. Defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden among children living in poverty. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2007, 77, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkovic, G.J. Lost Childhoods: The Plight of The Parentified Child; Brunner/Mazel: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, P.; Hooper, L.M.; Sandage, S.; Hannah, N.J. Parentification and mental health symptoms: The mediating effects of perceived unfairness and self-regulation. J. Fam. Ther. 2011, 35, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social identity. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Leary, M.R., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 462–479. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H. Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting 2012, 12, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.K.; Tseng, V. Parenting in Asians. In Handbook of Parenting; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; Volume 4, pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.K. Filial piety and loyalty: Two types of social identification in Confucianism. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.Y.F. Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In The Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Bond, M.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L. Family functioning, filial piety and adolescent psychosocial competence in Chinese single-mother families experiencing economic disadvantage: Implications for social work. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2016, 46, 1809–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.C. Parent-child relationship and filial piety affect parental health and well-being. Sociol. Anthropol. 2017, 5, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, P.L. Children’s provision of family caregiving: Benefit or burden? Child Dev. Perspect. 2010, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Updegraff, K.A.; Delgado, M.Y.; Wheeler, L.A. Exploring mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with sons versus daughters: Links to adolescent adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetherington, E.M. Coping with Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage: A Risk and Resiliency Perspective; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Juang, L.P.; Cookston, J.T. A longitudinal study of family obligation and depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- East, P.L.; Weisner, T.S.; Slonim, A. Youths’ caretaking of their adolescent sisters’ children: Results from two longitudinal studies. J. Fam. Issues 2009, 30, 1671–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatnick, M.R. Too old for child care? Too young for self care? Negotiating afterschool arrangements for middle school. J. Fam. Issues 2002, 23, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.M.; Fung, T.C.T. Reliability and validity of K10 and K6 in screening depressive symptoms in Hong Kong adolescents. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2014, 9, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M.; Ho, S.; Kan, C.S.; Hung, C.H.; Chen, C.N. Evaluation of the Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: A cross-cultural perspective. Int. J. Psychosom. 1993, 40, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.M.; Wing, Y.K.; Kwong, P.K.; Shum, A.L.K. Validation of the Chinese-Cantonese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and comparison with the Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1999, 100, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurkovic, G.J.; Kuperminc, G.P.; Sarac, T.; Weisshaar, D. Role of filial responsibility in the post-war adjustment of Bosnian young adolescents. J. Emot. Abus. 2005, 5, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperminc, G.P.; Jurkovic, G.J.; Casey, S. Relation of filial responsibility to the personal and social adjustment of Latino adolescents from immigrant families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y. Filial responsibilities and adolescent wellbeing among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. 2022; Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for The Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, B.D. Parental alienation and the dynamics of the enmeshed parent–child dyad: Adultification, parentification, and infantilization. Fam. Court. Rev. 2011, 49, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshvari, F.; Meigouni, K.M.A.; Rezabakhsh, H.; Pashang, S. Predicting Adolescent Girls’ Anxiety by Early Maladaptive Schemas of their Mothers with the Mediation of their Self-Differentiation and Early Maladaptive Schemas. J. Appl. Psychol. Res. 2021, 11, 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Endler, N.S.; Parker, J.D. Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLanahan, S.; Sandefur, G.D. Growing Up with A Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R.S. Growing up a little faster: The experience of growing up in a single-parent household. J. Soc. Issues 1979, 35, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.M.; Marotta, S.A.; Lanthier, R.P. Predictors of growth and distress following childhood parentification: A retrospective exploratory study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2008, 17, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal distress | 2.54 | 0.89 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Instrumental filial responsibilities | 1.89 | 0.78 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3. Emotional filial responsibilities | 2.30 | 0.61 | −0.01 | 0.37 *** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4. Anxiety | 2.09 | 0.56 | 0.12 * | 0.00 | −0.08 | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. Depression | 1.97 | 0.54 | 0.13 * | −0.07 | −0.19 ** | 0.48 *** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6. Adolescent gender (boys = −1; girls = 1) | N.A. | N.A. | 0.03 | 0.13 * | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||

| 7. Adolescent age | 13.53 | 2.10 | −0.02 | 0.13 * | 0.13 * | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| 8. Sibling birth order | N.A. | N.A. | 0.01 | 0.34 *** | −0.12 ** | 0.12 * | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 1.00 | |

| 9. No. of children in the family | 1.76 | 0.77 | 0.06 | 0.44 *** | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.15 ** | 0.72 *** | 1.00 |

| 10. Mother’s educational level | N.A. | N.A. | 0.12 * | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.06 |

| Moderator | Anxiety | Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | B | SE | β | ||

| Instrumental filial responsibility | Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender of adolescents | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.15 * | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | |

| Age of adolescents | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Sibling birth order | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.11 † | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

| No. of children | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.03 | |

| Mother’s education | 0 | 0.04 | 0.00 | ||||

| Step 2 | |||||||

| Maternal distress | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 † | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.11 † | |

| Instrumental filial responsibility | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 0.05 | −0.16 * | |

| Step 3 | |||||||

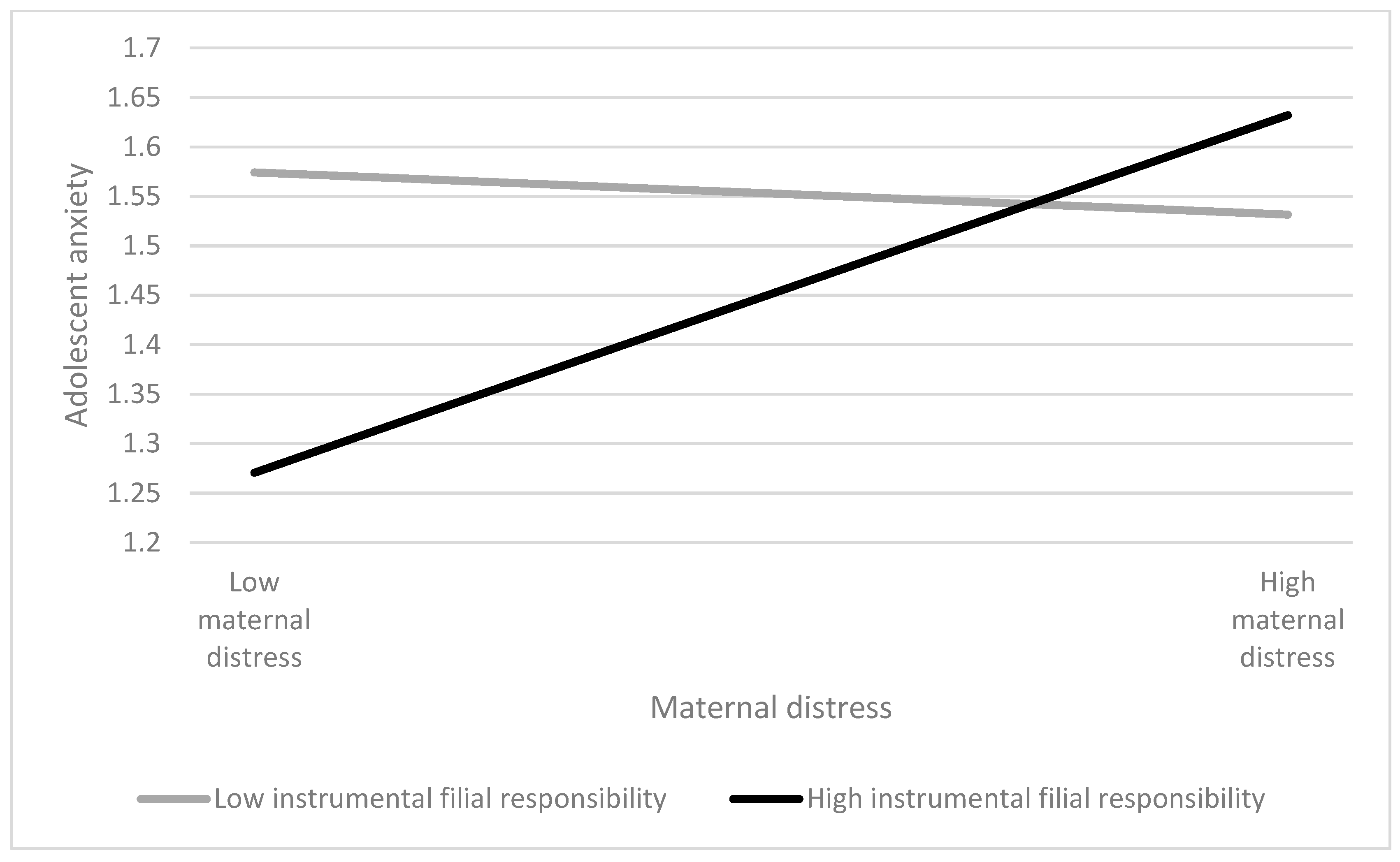

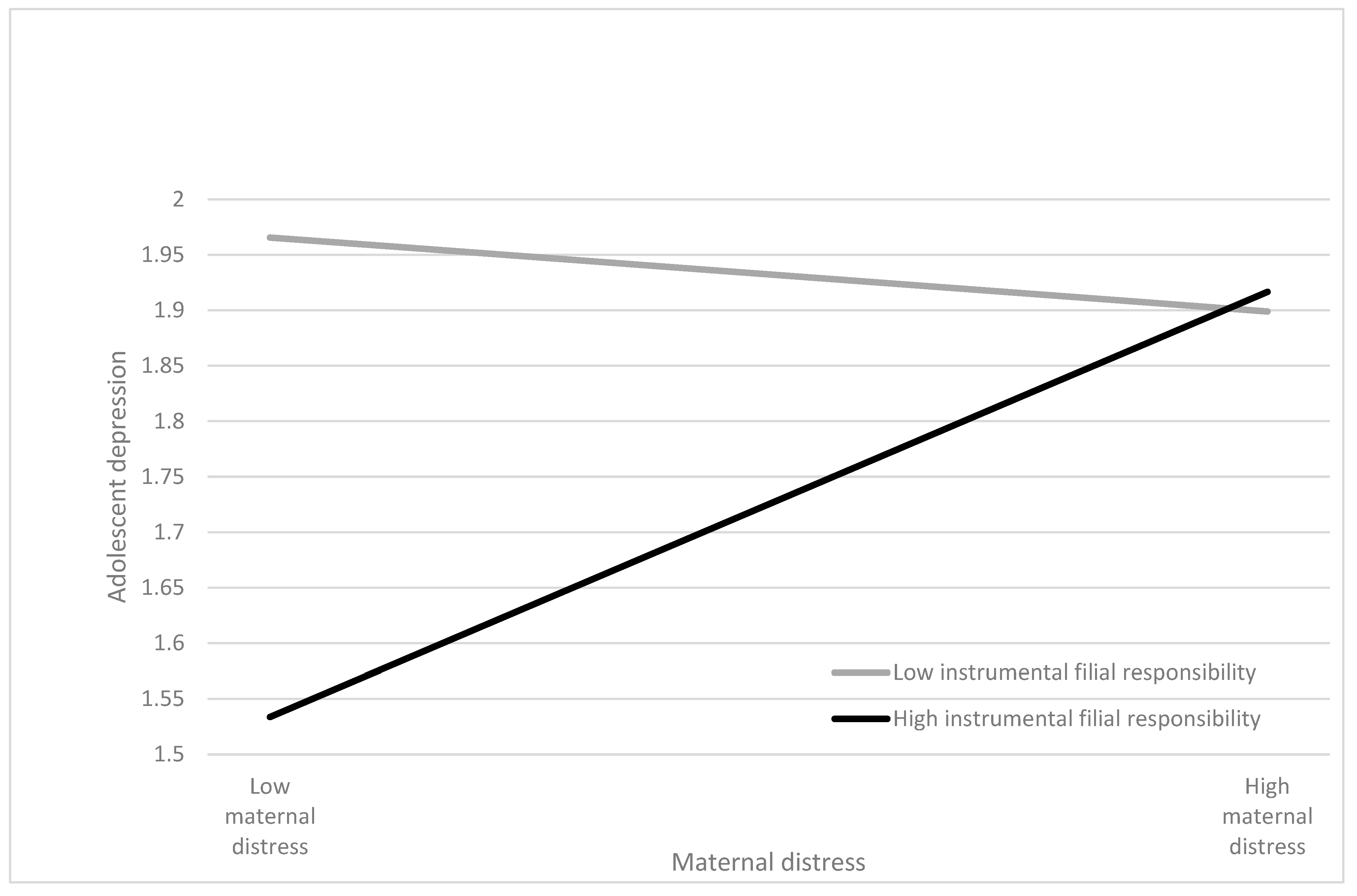

| Maternal distress × Instrumental filial responsibility | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 * | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.13 * | |

| Gender as a moderator: | |||||||

| Step 4 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Gender | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.11 † | |

| Instrumental filial responsibility × Gender | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.10 † | |

| Step 5 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Instrumental filial responsibility × Gender | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.11 † | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | |

| Age as a moderator | |||||||

| Step 4 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | |

| Instrumental filial responsibility × Age | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.12 † | |

| Step 5 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Instrumental filial responsibility × Age | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.09 | |

| Emotional filial responsibility | Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender of adolescents | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.14 * | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

| Age of adolescents | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.10† | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| Sibling birth order | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| No. of children | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.04 | |

| Mother’s education | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | |

| Step 2 | |||||||

| Maternal distress | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 † | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.09 | |

| Emotional filial responsibility | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.21 | 0.05 | −0.23 *** | |

| Step 3 | |||||||

| Emotional filial responsibility × Maternal distress | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.16 ** | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | |

| Gender as a moderator: | |||||||

| Step 4 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Gender | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.01 | |

| Emotional filial responsibility × Gender | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| Step 5 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Emotional filial responsibility × Gender | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.12 * | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |

| Age as a moderator | |||||||

| Step 4 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 † | |

| Emotional filial responsibility × Age | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.08 | |

| Step 5 | |||||||

| Maternal distress × Emotional filial responsibility × Age | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | |

| Moderator | Predictor | Regression Coefficient (β) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Boys | Girls | |||

| Anxiety | |||||

| Instrumental filial responsibility | Higher level (+1 SD) | Maternal distress | 0.29 ** | N.A. | N.A. |

| Lower level (−1 SD) | −0.03 | N.A. | N.A. | ||

| Emotional filial responsibility | Higher level (+1 SD) | Maternal distress | 0.34 ** | 0.13 | 0.56 *** |

| Lower level (−1 SD) | −0.14 | −0.04 | −0.23 | ||

| Depression | |||||

| Instrumental filial responsibility | Higher level (+1 SD) | Maternal distress | 0.32 ** | N.A. | N.A. |

| Lower level (−1 SD) | −0.06 | N.A. | N.A. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L.; To, S.-M.; Ngai, S.-W. Maternal Distress and Adolescent Mental Health in Poor Chinese Single-Mother Families: Filial Responsibilities—Risks or Buffers? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075363

Leung JTY, Shek DTL, To S-M, Ngai S-W. Maternal Distress and Adolescent Mental Health in Poor Chinese Single-Mother Families: Filial Responsibilities—Risks or Buffers? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(7):5363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075363

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeung, Janet T. Y., Daniel T. L. Shek, Siu-Ming To, and So-Wa Ngai. 2023. "Maternal Distress and Adolescent Mental Health in Poor Chinese Single-Mother Families: Filial Responsibilities—Risks or Buffers?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 7: 5363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075363

APA StyleLeung, J. T. Y., Shek, D. T. L., To, S.-M., & Ngai, S.-W. (2023). Maternal Distress and Adolescent Mental Health in Poor Chinese Single-Mother Families: Filial Responsibilities—Risks or Buffers? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075363