Web-Based Physical Activity Interventions to Promote Resilience and Mindfulness Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.2.1. Resilience

2.2.2. Mindfulness

2.3. Intervention Conditions

2.3.1. WeActive Intervention Group

2.3.2. WeMindful Intervention Group

2.4. Implementation Strategy

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

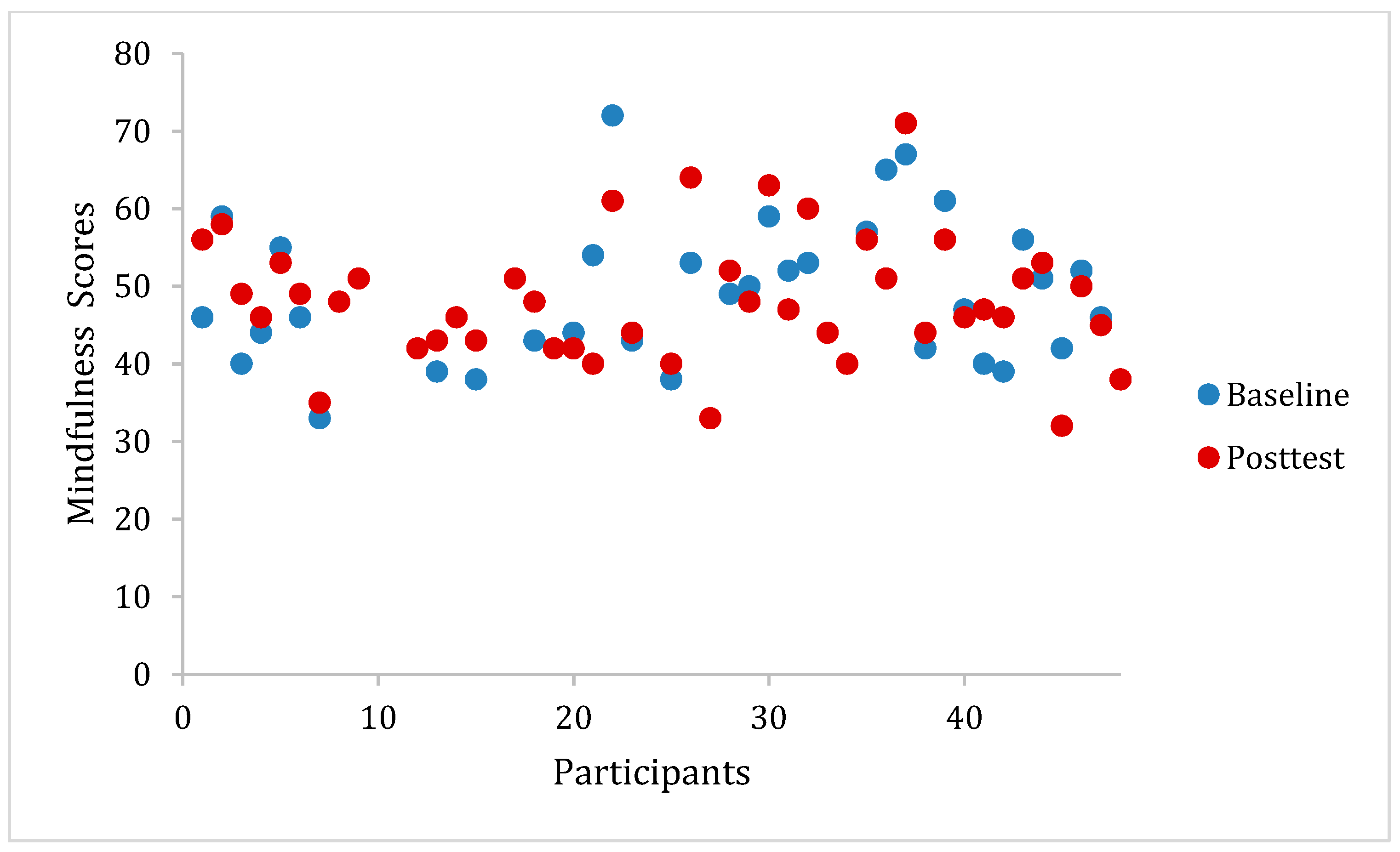

3.2. Intervention Effects on Resilience and Mindfulness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birmingham, W.C.; Wadsworth, L.L.; Lassetter, J.H.; Graff, T.C.; Lauren, E.; Hung, M. COVID-19 Lockdown: Impact on College Students’ Lives. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalsky, R.J.; Farney, T.M.; Kline, C.E.; Hinojosa, J.N.; Creasy, S.A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Lifestyle Behaviors in U.S. College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Torrano, D.; Ibrayeva, L.; Sparks, J.; Lim, N.; Clementi, A.; Almukhambetova, A.; Nurtayev, Y.; Muratkyzy, A. Mental Health and Well-Being of University Students: A Bibliometric Mapping of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisto, A.; Vicinanza, F.; Campanozzi, L.L.; Ricci, G.; Tartaglini, D.; Tambone, V. Towards a Transversal Definition of Psychological Resilience: A Literature Review. Medicina 2019, 55, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seligman, M.E. Building Resilience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, M.T. Examining the Relationships between Resilience, Mental Health, and Academic Persistence in Undergraduate College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moljord, I.E.O.; Moksnes, U.K.; Espnes, G.A.; Hjemdal, O.; Eriksen, L. Physical Activity, Resilience, and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2014, 2, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; De Los Santos, J.A.A.; Falguera, C.C. Social and Emotional Loneliness among College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Predictive Role of Coping Behaviors, Social Support, and Personal Resilience. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitsky, B.; Findling, Y.; Ereli, A.; Hendel, T. Anxiety and Coping Strategies among Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 46, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, R.; Babić, M.; Rastović, P.; Ćurlin, M.; Šimić, J.; Mandić, K.; Pavlović, K. Resilience in Health and Illness. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 226–232. [Google Scholar]

- Oehme, K.; Perko, A.; Clark, J.; Ray, E.C.; Arpan, L.; Bradley, L. A Trauma-Informed Approach to Building College Students’ Resilience. J. Evid.-Based Soc. Work 2019, 16, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enrique Roig, A.; Mooney, O.; Salamanca-Sanabria, A.; Lee, C.T.; Farrell, S.; Richards, D. Assessing the Efficacy and Acceptability of a Web-Based Intervention for Resilience Among College Students: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e20167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunston, E.; Messina, E.; Coelho, A.; Chriest, S.; Waldrip, M.; Vahk, A.; Taylor, K. Physical Activity Is Associated with Grit and Resilience in College Students: Is Intensity the Key to Success? J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 70, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.R. The Necessary and Sufficient Conditions of Therapeutic Personality Change. Psychotherapy 2007, 44, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belcher, B.R.; Zink, J.; Azad, A.; Campbell, C.E.; Chakravartti, S.P.; Herting, M.M. The Roles of Physical Activity, Exercise, and Fitness in Promoting Resilience during Adolescence: Effects on Mental Well-Being and Brain Development. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2021, 6, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arida, R.M.; Teixeira-Machado, L. The Contribution of Physical Exercise to Brain Resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 626769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.P.; Gerbarg, P.L. Yoga Breathing, Meditation, and Longevity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1172, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waechter, R.L.; Wekerle, C. Promoting Resilience among Maltreated Youth Using Meditation, Yoga, Tai Chi and Qigong: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2015, 32, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, J.; Dufour, G.; Vainre, M.; Wagner, A.P.; Stochl, J.; Benton, A.; Lathia, N.; Howarth, E.; Jones, P.B. A Mindfulness-Based Intervention to Increase Resilience to Stress in University Students (the Mindful Student Study): A Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e72–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akeman, E.; Kirlic, N.; Clausen, A.N.; Cosgrove, K.T.; McDermott, T.J.; Cromer, L.D.; Paulus, M.P.; Yeh, H.-W.; Aupperle, R.L. A Pragmatic Clinical Trial Examining the Impact of a Resilience Program on College Student Mental Health. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Chadi, N.; Shrier, L. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Adolescent Health. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2019, 31, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J.; Hanh, T.N. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness; Delta: Surrey, UK, 2009; ISBN 0-307-56757-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, B.; Lindsay, E.K.; Greco, C.M.; Brown, K.W.; Smyth, J.M.; Wright, A.G.C.; Creswell, J.D. Psychological Mechanisms Driving Stress Resilience in Mindfulness Training: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2019, 38, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorski, M.; Suchorzynska, A. Psychobehavioral Effects of Meditation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1023, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, K.; Harrison, M.; Adams, M.; Quin, R.H.; Greeson, J. Developing Mindfulness in College Students through Movement-Based Courses: Effects on Self-Regulatory Self-Efficacy, Mood, Stress, and Sleep Quality. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 58, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greeson, J.M.; Juberg, M.K.; Maytan, M.; James, K.; Rogers, H. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Koru: A Mindfulness Program for College Students and Other Emerging Adults. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, P.; Niemann, L.; Schmidt, S.; Walach, H. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Health Benefits. A Meta-Analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiswinkler, L.; Unterrainer, H.F. The Relationship between Yoga Involvement, Mindfulness and Psychological Well-Being. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 26, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskins, R.; Jennings, E.; Thind, H.; Becker, B.; Bock, B. Acute and Cumulative Effects of Vinyasa Yoga on Affect and Stress among College Students Participating in an Eight-Week Yoga Program: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2014, 24, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman-Mueller, H.; Wilson, T.; Jung, A.-K.; Kimura, A.; Tarrant, J. IRest Yoga-Nidra on the College Campus: Changes in Stress, Depression, Worry, and Mindfulness. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2013, 23, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, N.T.; van Vugt, M.K.; Vago, D.R.; Schmalzl, L.; Saron, C.D.; Olendzki, A.; Meissner, T.; Lazar, S.W.; Kerr, C.E.; Gorchov, J.; et al. Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marenus, M.W.; Murray, A.; Friedman, K.; Sanowski, J.; Ottensoser, H.; Cahuas, A.; Kumaravel, V.; Chen, W. Feasibility and Effectiveness of the Web-Based WeActive and WeMindful Interventions on Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, e8400241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, K.; Marenus, M.W.; Murray, A.; Cahuas, A.; Ottensoser, H.; Sanowski, J.; Chen, W. Enhancing Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being in College Students during COVID-19 through WeActive and WeMindful Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, A.; Andrews, K.; He, Z.; Chen, W. The Effects of Different Types of Physical Activities on Stress and Anxiety in College Students. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 5385–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Stavrulaki, E. The Efficacy of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention for College Students Under Extremely Stressful Conditions. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 3086–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Forde, D.R.; Stein, M.B. Demographic and Childhood Environmental Predictors of Resilience in a Community Sample. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009, 43, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, S.P.; Moore, E.W.G.; Newton, M.; Galli, N.A. Validity and Reliability of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in Competitive Sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 23, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, J.; Strauss, C.; Crane, C.; Barnhofer, T.; Karl, A.; Cavanagh, K.; Kuyken, W. Examining the Factor Structure of the 39-Item and 15-Item Versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire before and after Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for People with Recurrent Depression. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WOOP My Life. Available online: https://woopmylife.org (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Li, N.; Broyles, A.; Musoka, L.; Correa-Fernández, V. Validity of the 15-Item Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire among an Ethnically Diverse Sample of University Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 71, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Fledderus, M.; Veehof, M.; Baer, R. Psychometric Properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Depressed Adults and Development of a Short Form. Assessment 2011, 18, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mothes, H.; Klaperski, S.; Seelig, H.; Schmidt, S.; Fuchs, R. Regular Aerobic Exercise Increases Dispositional Mindfulness in Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2014, 7, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulmer, C.S.; Stetson, B.A.; Salmon, P.G. Mindfulness and Acceptance Are Associated with Exercise Maintenance in YMCA Exercisers. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, J. Mindfulness: A Proposed Psychological Mechanism of Aerobic Exercise That Contributes to Psychological Well Being. Ph.D. Thesis, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Lee, E.K.P.; Mak, E.C.W.; Ho, C.Y.; Wong, S.Y.S. Mindfulness-Based Interventions: An Overall Review. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 138, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, M.; Mogle, J.; Elavsky, S. The Daily Influences of Yoga on Relational Outcomes Off of the Mat. Int. J. Yoga 2019, 12, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Qi, X.; He, Z.; Chen, S.; Pedersen, S.J.; Cooley, P.D.; Spencer-Rodgers, J.; He, S.; Zhu, X. The Immediate and Durable Effects of Yoga and Physical Fitness Exercises on Stress. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khramtsova, I.; Glascock, P. Outcomes of an Integrated Journaling and Mindfulness Program on a US University Campus. Stud. ŞI Cercet. 2010, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Strick, M.; Papies, E.K. A Brief Mindfulness Exercise Promotes the Correspondence between the Implicit Affiliation Motive and Goal Setting. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Husband, C.; La, H.; Juba, M.; Loucks, R.; Harrison, A.; Rhodes, R.E. Development of a Self-Guided Web-Based Intervention to Promote Physical Activity Using the Multi-Process Action Control Framework. Internet Interv. 2019, 15, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Cisgender female | 61 | 85% |

| Cisgender male | 7 | 10% | |

| Transgender and Gender Non-conforming (TGNC) | 4 | 6% | |

| Race | Asian | 14 | 19% |

| Black or African American | 4 | 6% | |

| White | 47 | 65% | |

| Multiracial | 7 | 9% | |

| Education status | 1st year | 7 | 10% |

| 2nd year | 9 | 13% | |

| 3rd year | 15 | 21% | |

| 4th year | 14 | 19% | |

| Master’s | 13 | 18% | |

| Professional | 2 | 3% | |

| Doctoral | 12 | 17% |

| Variable | WeActive (n = 44) | WeMindful (n = 28) | Total (n = 72) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Baseline Resilience | 26.48 | 6.50 | 24.64 | 5.50 | 25.76 | 6.16 |

| Post-test Resilience | 26.80 | 7.87 | 26.75 | 5.54 | 26.78 | 7.01 |

| Baseline Mindfulness | 33.20 | 4.74 | 33.79 | 5.06 | 33.43 | 4.84 |

| Post-test Mindfulness | 36.05 | 5.16 | 36.61 | 6.37 | 36.26 | 5.62 |

| Baseline Describing | 9.07 | 1.27 | 9.29 | 1.36 | 9.15 | 1.30 |

| Post-test Describing | 9.23 | 3.03 | 10.25 | 3.22 | 9.63 | 3.12 |

| Baseline Acting with Awareness | 7.95 | 2.33 | 8.79 | 2.36 | 8.28 | 2.36 |

| Post-test Acting with Awareness | 10.23 | 2.56 | 9.46 | 2.60 | 9.93 | 2.59 |

| Baseline Non-Judging | 7.64 | 3.57 | 7.14 | 2.90 | 7.44 | 3.31 |

| Post-Test Non-Judging | 8.27 | 2.20 | 7.86 | 1.20 | 8.11 | 2.12 |

| Baseline Non-Reactivity | 8.55 | 2.54 | 8.57 | 1.86 | 8.56 | 2.28 |

| Post-Test Non-Reactivity | 8.32 | 2.38 | 9.04 | 2.58 | 8.60 | 2.47 |

| Condition | Group | % or Mean (SD) | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3x/month exercise | WeActive | 48% | 0.77 | 59.91 | 0.443 |

| WeMindful | 38% | ||||

| 3x/month yoga | WeActive | 17% | −0.81 | 51.94 | 4.24 |

| WeMindful | 24% | ||||

| 3x/month therapist | WeActive | 21% | −2.51 | 49.15 | 0.015 * |

| WeMindful | 48% | ||||

| Health Rating | WeActive | 3.14 (1.02) | −0.66 | 72.29 | 0.512 |

| WeMindful | 3.28 (0.75) | ||||

| Baseline Resilience | 0.61 | 68.50 | 0.545 | ||

| Baseline Mindfulness | −0.12 | 71.37 | 0.905 |

| Source | Measure | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Resilience | 2.56 | 0.114 | 0.039 |

| Mindfulness | 5.18 | 0.026 * | 0.070 | |

| Describing | 0.02 | 0.889 | 0.000 | |

| Acting with Awareness | 7.32 | 0.009 ** | 0.096 | |

| Non-Judging | 5.47 | 0.022 * | 0.073 | |

| Non-Reactivity | 0.07 | 0.796 | 0.001 | |

| Condition | Resilience | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.000 |

| Mindfulness | 0.33 | 0.568 | 0.005 | |

| Describing | 0.44 | 0.510 | 0.006 | |

| Acting with Awareness | 0.62 | 0.436 | 0.009 | |

| Non-Judging | 0.83 | 0.366 | 0.012 | |

| Non-Reactivity | 1.43 | 0.235 | 0.020 | |

| Time * Condition | Resilience | 1.81 | 0.183 | 0.026 |

| Mindfulness | 0.00 | 0.948 | 0.000 | |

| Describing | 0.23 | 0.635 | 0.003 | |

| Acting with Awareness | 1.04 | 0.312 | 0.015 | |

| Non-Judging | 0.03 | 0.870 | 0.00 | |

| Non-Reactivity | 1.42 | 0.238 | 0.020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marenus, M.W.; Cahuas, A.; Hammoud, D.; Murray, A.; Friedman, K.; Ottensoser, H.; Sanowski, J.; Kumavarel, V.; Chen, W. Web-Based Physical Activity Interventions to Promote Resilience and Mindfulness Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085463

Marenus MW, Cahuas A, Hammoud D, Murray A, Friedman K, Ottensoser H, Sanowski J, Kumavarel V, Chen W. Web-Based Physical Activity Interventions to Promote Resilience and Mindfulness Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(8):5463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085463

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarenus, Michele W., Ana Cahuas, Dianna Hammoud, Andy Murray, Kathryn Friedman, Haley Ottensoser, Julia Sanowski, Varun Kumavarel, and Weiyun Chen. 2023. "Web-Based Physical Activity Interventions to Promote Resilience and Mindfulness Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 8: 5463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085463