Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome amongst Females Aged between 15 and 45 Years at a Major Women’s Hospital in Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Considerations and Sample Size Calculation

3. Results

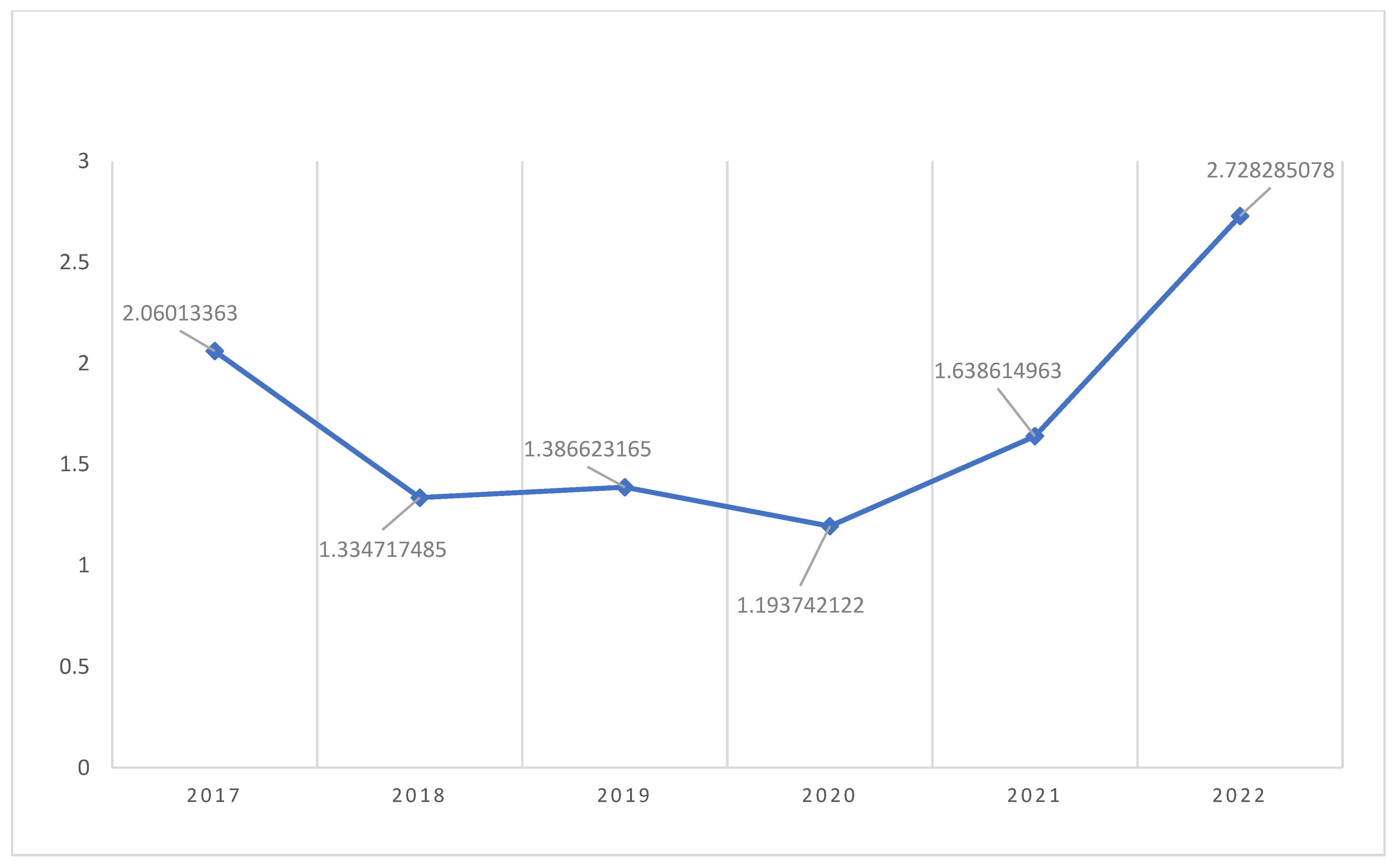

3.1. Proportion of Women with a Diagnosis of PCOS Aged between 15 and 45 Years, Seen at Latifa Hospital, Dubai, UAE, from 2017 to 2022

3.2. Comparing the Demographic, Clinical, Endocrine, Hormonal and Metabolic Profile of Women with PCOS with Controls in a Subset of 120 Women Aged 15–45 Years Seen at Latifa Hospital from 3 October 2022 to 30 November 2022

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deswal, R.; Narwal, V.; Dang, A.; Pundir, C.S. The Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Brief Systematic Review. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 13, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoula, Z.; Salman, M.; Atiomo, W. Evaluating the Association between Endometrial Cancer and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Alzaabi, M. Higher and Increasing Incidence of Cancer between the Age of 20-49 Years in the UAE Population; A Focus Analysis of the UAE National Cancer Registry Data 2015–2017. J. Oncol. Res. Rev. Rep. 2021, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesta, C.E.; Öberg, A.S.; Ibrahimson, A.; Yusuf, I.; Larsson, H.; Almqvist, C.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Bulik, C.M.; Fernández de la Cruz, L.; Mataix-Cols, D.; et al. Maternal Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Risk of Neuropsychiatric Disorders in Offspring: Prenatal Androgen Exposure or Genetic Confounding? Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitoun, B.; Al Kubaisi, A.; AlQattan, N.; Alassouli, Y.; Mohammad, A.; Alameeri, H.; Mohammed, G. Polycystic ovarian syndrome awareness among females in the UAE: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh Asghari, K.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Alizadeh, M.; Sanaie, S.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Kolahi, A.-A.; Avery, J.; Safiri, S. Burden of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in the Middle East and North Africa Region, 1990–2019. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global Burden of 87 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, T.B.; Chatterji, S.; Villanueva, M.; Bendib, L.; Çelik, C.; Sadana, R.; Valentine, N.; Ortiz, J.; Tandon, A.; Salomon, J.; et al. WHO Multi-Country Survey Study on Health and Responsiveness; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- World Health Organization (WHO). United Arab Emirates World Health Survey 2003; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Pramodh, S. Exploration of Lifestyle Choices, Reproductive Health Knowledge, and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) Awareness Among Female Emirati University Students. Int. J. Women’s Health 2020, 12, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attlee, A.; Nusralla, A.; Eqbal, R.; Said, H.; Hashim, M.; Obaid, R.S. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in University Students: Occurrence and Associated Factors. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 8, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Eshre, R.; ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 Consensus on Diagnostic Criteria and Long-Term Health Risks Related to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Hum. Reprod. 2004, 19, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmina, E. Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: From NIH Criteria to ESHRE-ASRM Guidelines. Minerva Ginecol. 2004, 56, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Dewailly, D.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; Futterweit, W.; Janssen, O.E.; Legro, R.S.; Norman, R.J.; Taylor, A.E.; et al. Criteria for Defining Polycystic Ovary Syndrome as a Predominantly Hyperandrogenic Syndrome: An Androgen Excess Society Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 4237–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaolino, P.; Morra, I.; Della Corte, L.; Sparice, S.; Di Carlo, C.; Nappi, C.; Bifulco, G. Serum Anti-Mullerian Hormone Levels after Ovarian Drilling for the Second-Line Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Pilot-Randomized Study Comparing Laparoscopy and Transvaginal Hydrolaparoscopy. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2017, 33, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoroh, E.M.; Hooper, W.C.; Atrash, H.K.; Yusuf, H.R.; Boulet, S.L. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome among the Privately Insured, United States, 2003–2008. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2012, 207, 299.e1–299.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, S.B.; Black, M.H.; Smith, N.; Martinez, M.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Porter, A.H.; Koebnick, C. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Adolescents. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, J.C.; Feigenbaum, S.L.; Yang, J.; Pressman, A.R.; Selby, J.V.; Go, A.S. Epidemiology and Adverse Cardiovascular Risk Profile of Diagnosed Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miazgowski, T.; Martopullo, I.; Widecka, J.; Miazgowski, B.; Brodowska, A. National and Regional Trends in the Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome since 1990 within Europe: The Modeled Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourhoseini, S.A.; Babazadeh, R.; Mazlom, S.R. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Iranian Adolescent Girls Based on Adults and Adolescents’ Diagnostic Criteria in Mashhad City. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2022, 23, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, M.A.; Rashid, A.; Sahu, D.; Nisar, S.; Wani, I.A.; Khan, J. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) among Reproductive Age Women from Kashmir Valley: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obs. 2020, 149, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, J.A.; Cunningham, J.; O’Dea, K.; Dunbar, T.; Norman, R.J. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in a Sample of Indigenous Women in Darwin, Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 196, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juber, N.F.; Abdulle, A.; AlJunaibi, A.; AlNaeemi, A.; Ahmad, A.; Leinberger-Jabari, A.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; AlZaabi, E.; Al-Maskari, F.; AlAnouti, F.; et al. Association Between Self-Reported Polycystic Ovary Syndrome with Chronic Diseases Among Emiratis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the UAE Healthy Future Study. Int. J. Women’s Health 2023, 15, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) for 359 Diseases and Injuries and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1859–1922. [CrossRef]

- Dalibalta, S.; Abukhaled, Y.; Samara, F. Factors Influencing the Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) in the United Arab Emirates. Rev. Environ. Health 2022, 37, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Kim, W.; Choi, M.; Shin, J. Did the Increase in Sitting Time Due to COVID-19 Lead to Obesity in Adolescents? BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBlooshi, S.; AlFalasi, M.; Taha, Z.; El Ktaibi, F.; Khalid, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Quarantine on Lifestyle Indicators in the United Arab Emirates. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1123894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radwan, H.; Al Kitbi, M.; Hasan, H.; Al Hilali, M.; Abbas, N.; Hamadeh, R.; Saif, E.R.; Naja, F. Indirect Health Effects of COVID-19: Unhealthy Lifestyle Behaviors during the Lockdown in the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Xin, J.; Zhou, P.; Tang, J.; Xie, H.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D. Bidirectional Association between Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Periodontal Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1008675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Saddik, B.; El-Faramawi, M.; Hamidi, S.; Basheti, M.; Basheti, M. Oral Health Knowledge and Behavior among Adults in the United Arab Emirates. Biomed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7568679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, V.; Escalda, C.; Proença, L.; Mendes, J.J.; Botelho, J. Is There a Bidirectional Association between Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Periodontitis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Lv, W.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S. Correlation Analysis of Gut Microbiota and Serum Metabolome With Porphyromonas Gingivalis-Induced Metabolic Disorders. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 858902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharuman, S.; Ajith Kumar, S.; Kanakasabapathy Balaji, S.; Vishwanath, U.; Parthasarathy Parameshwari, R.; Santhanakrishnan, M. Evaluation of Levels of Advanced Oxidative Protein Products in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome with and without Chronic Periodontitis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 16, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, J.A.; Schwartz, B.S.; Stewart, W.F.; Adler, N.E. Using Electronic Health Records for Population Health Research: A Review of Methods and Applications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2016, 37, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auble, B.; Elder, D.; Gross, A.; Hillman, J.B. Differences in the Management of Adolescents with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome across Pediatric Specialties. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2013, 26, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, V.; Shen, Y.; Yu, S.; Finan, S.; Pau, C.T.; Gainer, V.; Keefe, C.C.; Savova, G.; Murphy, S.N.; Cai, T.; et al. Identification of Subjects with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Using Electronic Health Records. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | No. Visitors | PCOS | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1796 | 37 | 2.06 |

| 2018 | 13,486 | 180 | 1.33 |

| 2019 | 13,486 | 187 | 1.38 |

| 2020 | 13,487 | 161 | 1.19 |

| 2021 | 13,487 | 221 | 1.63 |

| 2022 | 8980 | 245 | 2.72 |

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Bilateral polycystic ovarian syndrome [E28.2] | 1 | 0.1 |

| H/O polycystic ovarian syndrome [Z87.42] | 4 | 0.4 |

| History of PCOS [Z87.42] | 64 | 6.2 |

| History of polycystic ovarian disease [Z87.42] | 1 | 0.1 |

| History of polycystic ovarian syndrome [Z87.42] | 1 | 0.1 |

| History of polycystic ovaries [Z87.42] | 3 | 0.3 |

| PCO (polycystic ovaries) [E28.2] | 211 | 20.5 |

| PCOD (polycystic ovarian disease) [E28.2] | 82 | 8 |

| PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome) [E28.2] | 380 | 36.9 |

| Polycystic disease, ovaries [E28.2] | 102 | 9.9 |

| Polycystic ovarian disease [E28.2] | 45 | 4.4 |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome [E28.2] | 28 | 2.7 |

| Polycystic ovaries [E28.2] | 79 | 7.7 |

| Polycystic ovary disease [E28.2] | 2 | 0.2 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome [E28.2] | 6 | 0.6 |

| Polycystic ovary [E28.2] | 22 | 2.1 |

| Total | 1031 | 100 |

| Department | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| LH Antenatal Team1 | 16 | 1.6 |

| LH Antenatal Team2 | 20 | 1.9 |

| LH Colposcopy | 1 | 0.1 |

| LH Dietitian | 8 | 0.8 |

| LH Emergency | 4 | 0.4 |

| LH Endometriosis | 19 | 1.8 |

| LH Genetics | 2 | 0.2 |

| LH Gyne Oncology | 10 | 1 |

| LH Gynecology Team 1 | 345 | 33.5 |

| LH Gynecology Team 2 | 186 | 18 |

| LH Lab | 117 | 11.3 |

| LH MFM-AD | 3 | 0.3 |

| LH MFM-EP | 33 | 3.2 |

| LH MFM-PA | 11 | 1.1 |

| LH Minimally Invasive | 25 | 2.4 |

| LH OBS Medical | 2 | 0.2 |

| LH PED Surgery | 1 | 0.1 |

| LH Pediatrics | 1 | 0.1 |

| LH Pre-Conception | 1 | 0.1 |

| LH Procedure Clinic | 104 | 10.1 |

| LH Radiology | 109 | 10.6 |

| LH Staff Clinic | 1 | 0.1 |

| LH Urodynamic | 1 | 0.1 |

| LH Urogyne | 11 | 1.1 |

| Total | 1031 | 100 |

| PCOS (Mean +/− (SD) or %) | Controls (Mean +/− (SD) or %) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 28.16 (6.8) | 33.13 (6.1) | 0.002 |

| Emirati nationality (%) | 70.1 | 73.9 | 0.467 |

| Other nationality (%) | 29.9 | 26.1 | 0.467 |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.05 (1.78) | 1.39 (1.67) | 0.116 * |

| Number of living children | 0.56 (1.19) | 0.83 (1.302) | 0.146 * |

| Number of miscarriages | 0.27 (0.654) | 0.17 (.491) | 0.586 * |

| Currently pregnant? % | 9.3 | 26.1 | 0.04 |

| Systolic BP mm HG | 123.51 (12.785) | 110.78 (12.066) | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP mm HG | 78 (8.5) | 72.1 (8.41) | 0.003 |

| BMI | 29.34 (7.2) | 25.09 (7.4) | 0.024 |

| Luteinizing hormone miu/mL. | 9.1 (5.68) | 5.9 (3.6) | 0.065 |

| FSH miu/mL. | 5.2 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.2) | 0.184 |

| Prolactin miu/mL. | 423.7 (240) | 394 (187) | 0.694 |

| TSH uIU/L | 2.37 (1.57) | 1.49 (1.07) | 0.062 |

| Free T4 pmol/L | 15.6 (3.23) | 14.75 (1.9) | 0.6 |

| Insulin iIU/L. | 22 (14.8) | 11.9 (6.8) | 0.181 |

| Glucose, fasting mg/dL | 96.89 (40) | 89.39 (9.8) | 0.163 |

| Glucose, random mg/dL | 107.16 (32.74) | 107.83 (24.6) | 0.935 |

| Total cholesterol, fasting mg/dL | 181.94 (35.45) | 189.38 (36) | 0.506 |

| Triglycerides mg/dL | 97.42 (43.8) | 105.46 (59.96) | 0.653 |

| LDL-cholesterol mg/dL | 112.31 (30) | 118.31 (28) | 0.457 |

| HDL-cholesterol mg/dL | 53.87 (10.5) | 53.54 (16.43) | 0.945 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirza, F.G.; Tahlak, M.A.; Hazari, K.; Khamis, A.H.; Atiomo, W. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome amongst Females Aged between 15 and 45 Years at a Major Women’s Hospital in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095717

Mirza FG, Tahlak MA, Hazari K, Khamis AH, Atiomo W. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome amongst Females Aged between 15 and 45 Years at a Major Women’s Hospital in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(9):5717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095717

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirza, Fadi G., Muna A. Tahlak, Komal Hazari, Amar Hassan Khamis, and William Atiomo. 2023. "Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome amongst Females Aged between 15 and 45 Years at a Major Women’s Hospital in Dubai, United Arab Emirates" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 9: 5717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095717

APA StyleMirza, F. G., Tahlak, M. A., Hazari, K., Khamis, A. H., & Atiomo, W. (2023). Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome amongst Females Aged between 15 and 45 Years at a Major Women’s Hospital in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(9), 5717. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095717