Pilot Implementation of a Nutrition-Focused Community-Health-Worker Intervention among Formerly Chronically Homeless Adults in Permanent Supportive Housing

Abstract

1. Introduction

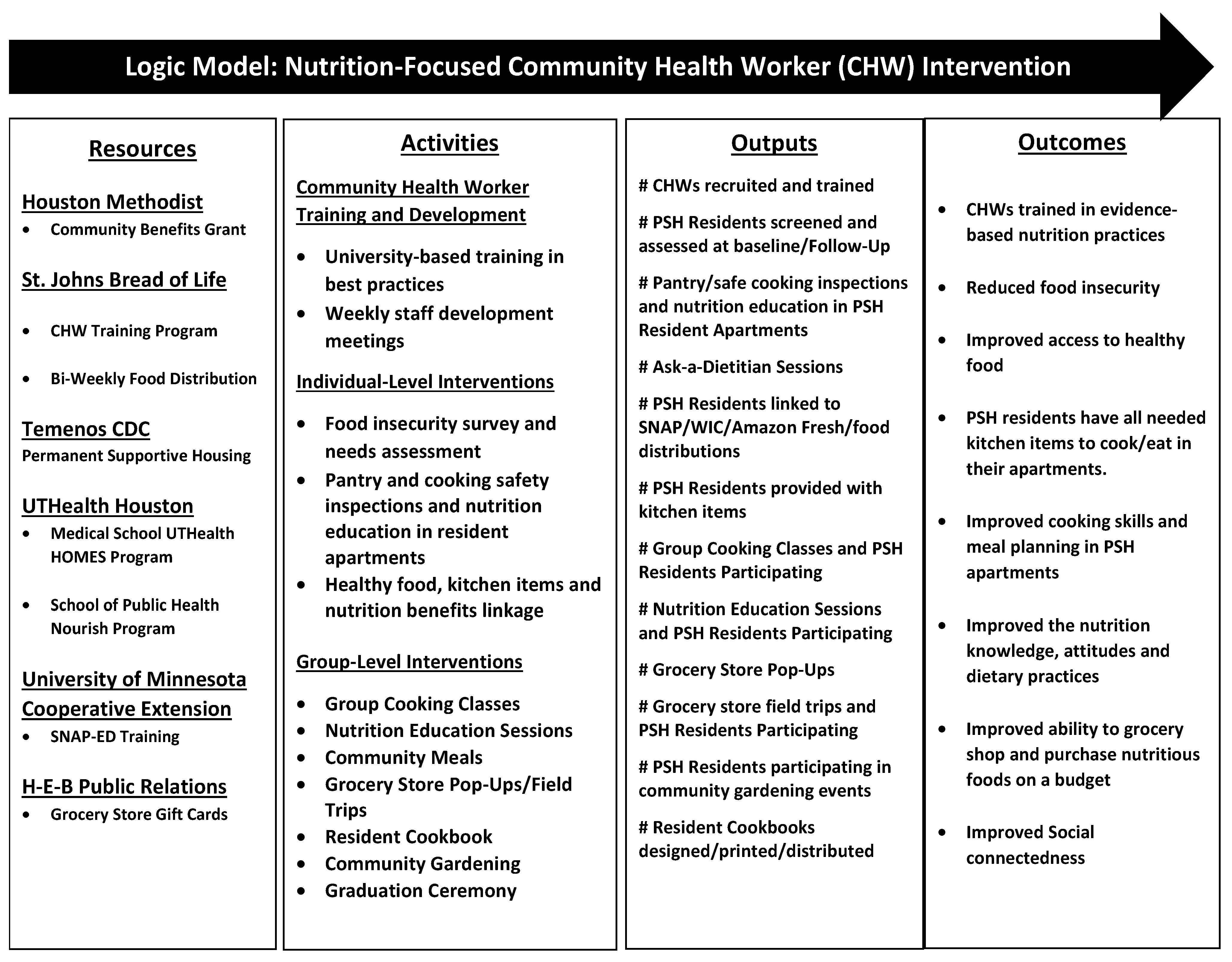

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Human-Centered Design

2.4. Pilot Intervention

2.5. Community-Health-Worker Training

2.6. Measures

2.7. PSH-Resident Feedback

- My Nutrition Goal(s) for Safe and Healthy Cooking/Eating:

- What did you like the most?

- What are some new things you learned from this group activity?

- Suggestions: How can we improve for our next class?

- What dish would you like to learn to cook next time?

- What nutrition project activities did you participate in?

- What nutrition project activities did you enjoy?

- What did you learn from participating in the project?

- How was the nutrition program helpful?

- Describe how you are using what you learned in the nutrition program?

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Baseline Screening Results

3.3. Follow-Up Surveys

3.4. Individual Level CHW Intervention

3.5. Group-Level CHW Intervention

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030 about the Objectives. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/about-objectives (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Holben, D.H.; Pheley, A.M. Diabetes risk and obesity in food-insecure households in rural Appalachian Ohio. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006, 3, A82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Schillinger, D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Thomsen, M.R.; Nayga, R.M. The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonyea, J.G.; O’Donnell, A.E.; Curley, A.; Trieu, V. Food insecurity and loneliness amongst older urban subsidised housing residents: The importance of social connectedness. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e5959–e5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. Food Insecurity: A Public Health Issue. Public Health Reports; Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 131, pp. 655–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Definitions of food security. Available online: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- Stinson, E.J.; Votruba, S.B.; Venti, C.; Perez, M.; Krakoff, J.; Gluck, M.E. Food Insecurity is Associated with Maladaptive Eating Behaviors and Objectively Measured Overeating. Obesity 2018, 26, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerman, W.J.; Wallston, K.A.; Osborn, C.Y.; Bian, A.; Schlundt, D.G.; Barto, S.D.; Rothman, R.L. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes self-care behaviours and glycaemic control. Diabet. Med. 2016, 33, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310, Erratum in J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, M.T.; Shim, R.S. Mental Illness Prevention and Mental Health Promotion: When, Who, and How. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Delahanty, L.M.; Terranova, J.; Steiner, B.; Ruazol, M.P.; Singh, R.; Shahid, N.N.; Wexler, D.J. Medically Tailored Meal Delivery for Diabetes Patients with Food Insecurity: A Randomized Cross-over Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, E.A.; Lahey, J.; Rhoades, H.; Henwood, B.F. Food Insecurity Among Formerly Homeless Individuals Living in Permanent Supportive Housing. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing: Defining “Chronically Homeless” Federal Register/Vol. 80, No. 233/Friday, 4 December 2015/Rules and Regulations 7 24 CFR Parts 91 and 578 [Docket No. FR–5809–F–01] RIN 2506–AC37. 2015. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-12-04/pdf/2015-30473.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Petersen, C.L.; Brooks, J.M.; Titus, A.J.; Vasquez, E.; Batsis, J.A. Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Functional Limitations in Older Adults from 2005–2014 NHANES. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 38, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henwood, B.F.; Cabassa, L.J.; Craig, C.M.; Padgett, D.K. Permanent supportive housing: Addressing homelessness and health disparities? Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103 (Suppl. S2), S188–S192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henwood, B.F.; Lahey, J.; Rhoades, H.; Winetrobe, H.; Wenzel, S.L. Examining the health status of homeless adults entering permanent supportive housing. J. Public Health 2018, 40, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Permanent Supportive Housing: Evaluating the Evidence for Improving Health Outcomes among People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brothers, S.; Lin, J.; Schonberg, J.; Drew, C.; Auerswald, C. Food insecurity among formerly homeless youth in supportive housing: A social-ecological analysis of a structural intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 245, 112724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Services for People Who Are Homeless; Advisory; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021; Publication No. PEP20-06-04-003. [Google Scholar]

- Molander, O.; Bjureberg, J.; Sahlin, H.; Beijer, U.; Hellner, C.; Ljótsson, B. Integrated cognitive behavioral treatment for substance use and depressive symptoms: A homeless case series and feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.W.; Wilkins, R.; Tjepkema, M.; O’Campo, P.J.; Dunn, J.R. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ 2009, 339, b4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, A.M.; Greene, R.N.; Dill, K.; Valvassori, P. The Impact of Homelessness on Mortality of Individuals Living in the United States: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2022, 33, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensken, W.P.; Krieger, N.I.; Berg, K.A.; Einstadter, D.; Dalton, J.E.; Perzynski, A.T. Health Status and Chronic Disease Burden of the Homeless Population: An Analysis of Two Decades of Multi-Institutional Electronic Medical Records. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2021, 32, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, T.; Teasdale, S.; Rocks, T.; Whatnall, M.; Schindlmayr, J.; Plain, J.; Latimer, G.; Roberton, M.; Harris, D.; Forsyth, A. Effectiveness of dietary interventions in mental health treatment: A rapid review of reviews. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 79, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, C. Using Human-Centered Design to Develop a Program to Engage South African Men Living with HIV in Care and Treatment. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2021, 9 (Suppl. S2), S234–S243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalition for the Homeless. Available online: https://www.homelesshouston.org/thewayhome#CoCPlans (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Tsai, J. Is the Housing First Model Effective? Different Evidence for Different Outcomes. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1376–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutko, P.; Ver Ploeg, M.; Farrigan, T. Characteristics and Influential Factors of Food Deserts, ERR-140; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, M.R. Chronic homelessness: Emergence of a public policy. Fordham Urban Law J. 2003, 30, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, E.; Neta, G.; Roberts, M.C. Complementary approaches to problem solving in healthcare and public health: Implementation science and human-centered design. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEO. The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design. 2015. Available online: http://www.designkit.org/resources/1 (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- University of Minnesota Extension, Cooking Matters for Adults, SNAP-Education. Available online: https://extension.umn.edu/nutrition-education/snap-ed-educational-offerings#:~:text=Cooking%20Matters%20for%20Adults%20(SNAP,foods%20and%20increasing%20physical%20activity (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Sharma, S.V.; McWhorter, J.W.; Chow, J.; Danho, M.P.; Weston, S.R.; Chavez, F.; Moore, L.S.; Almohamad, M.; Gonzalez, J.; Liew, E.; et al. Impact of a Virtual Culinary Medicine Curriculum on Biometric Outcomes, Dietary Habits, and Related Psychosocial Factors among Patients with Diabetes Participating in a Food Prescription Program. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhorter, J.W.; Raber, M.; Sharma, S.V.; Moore, L.S.; Hoelscher, D.M. The Nourish Program: An Innovative Model for Cooking, Gardening, and Clinical Care Skill Enhancement for Dietetics Students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 199–203, Erratum in J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service. Food Security Survey. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/survey-tools/#adult (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Parpouchi, M.; Moniruzzaman, A.; Russolillo, A.; Somers, J.M. Food insecurity among homeless adults with mental illness. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickhouser, S.; Wright, J.D.; Donley, A.M. Food Insecurity among Older Adults; AARP Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Opsomer, J.D.; Jensen, H.H.; Pan, S. An evaluation of the U.S. Department of Agriculture food security measure with generalized linear mixed models. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 421–427, Erratum in J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pinard, C.A.; Uvena, L.M.; Quam, J.B.; Smith, T.M.; Yaroch, A.L. Development and Testing of a Revised Cooking Matters for Adults Survey. Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condrasky, M.D.; Williams, J.E.; Catalano, P.M.; Griffin, S.F. Development of psychosocial scales for evaluating the impact of a culinary nutrition education program on cooking and healthful eating. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). Available online: https://sbmi.uth.edu/uth-big/services/redcap.htm (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J.; Begley, C.; Culler, R. Evaluation of partner collaboration to improve community-based mental health services for low-income minority children and their families. Eval. Program Plann. 2014, 45, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landers, P.; Shults, C. Pots, pans, and kitchen equipment: Do low-income clients have adequate tools for cooking. J. Ext. 2008, 46, 68–84. Available online: http://www.joe.org/joe/2008february/rb4.php (accessed on 31 May 2012).

- Curtis, P.J.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Effects on nutrient intake of a family-based intervention to promote increased consumption of low-fat starchy foods through education, cooking skills and personalised goal setting: The Family Food and Health Project. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Herrmann, R.O.; Warland, R.H. Perceived time pressure and recommended dietary practices: The moderating effect of knowledge of nutrition. J. Consum. Aff. 1993, 27, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw Score | Status | Baseline Numbers/Percentages (n = 83 Residents Screened) | Follow-Up Numbers/Percentages (n = 60 Residents Screened) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero | High Food Security | 20 (24%) | 16 (27%) |

| 1–2 | Marginal Food Security | 10 (12%) | 14 (23%) |

| 3–5 | Low Food Security | 24 (29%) | 13 (22%) |

| 6–10 | Very Low Food Security | 29 (35%) | 17 (28%) |

| 3–10 | Low/Very Low Food Security | 53 (64%) | 30 (50%) |

| Data Source | Project Activities | Major Theme(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Needs Assessment in REDCap | Baseline Screening | Lack of necessary kitchenware items in resident SROs for safe cooking and eating |

| Nutrition-based questions requested from residents | Nutrition Education Sessions | Knowledge gaps on how to purchase and prepare healthier food |

| Comment Cards | Nutrition Education Sessions | Positive perceptions of healthy food options |

| Comment Cards | Group Cooking Classes | Expanded preferences for healthy, easy-to-prepare foods |

| Comment Cards | Grocery Store Field Trips | Community re-entry |

| Comment Cards | Community Garden | Resident ownership |

| Brief feedback: enjoyment, learning, helpfulness, and application of nutrition activities | Cookbook Distribution |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamilton, J.E.; Guevara, D.C.; Steinfeld, S.F.; Jose, R.; Hmaidan, F.; Simmons, S.; Wong, C.W.; Smith, C.; Thibaudeau-Graczyk, E.; Sharma, S.V. Pilot Implementation of a Nutrition-Focused Community-Health-Worker Intervention among Formerly Chronically Homeless Adults in Permanent Supportive Housing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010108

Hamilton JE, Guevara DC, Steinfeld SF, Jose R, Hmaidan F, Simmons S, Wong CW, Smith C, Thibaudeau-Graczyk E, Sharma SV. Pilot Implementation of a Nutrition-Focused Community-Health-Worker Intervention among Formerly Chronically Homeless Adults in Permanent Supportive Housing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamilton, Jane E., Diana C. Guevara, Sara F. Steinfeld, Raina Jose, Farrah Hmaidan, Sarah Simmons, Calvin W. Wong, Clara Smith, Eva Thibaudeau-Graczyk, and Shreela V. Sharma. 2024. "Pilot Implementation of a Nutrition-Focused Community-Health-Worker Intervention among Formerly Chronically Homeless Adults in Permanent Supportive Housing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010108

APA StyleHamilton, J. E., Guevara, D. C., Steinfeld, S. F., Jose, R., Hmaidan, F., Simmons, S., Wong, C. W., Smith, C., Thibaudeau-Graczyk, E., & Sharma, S. V. (2024). Pilot Implementation of a Nutrition-Focused Community-Health-Worker Intervention among Formerly Chronically Homeless Adults in Permanent Supportive Housing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010108