Senior Theater Projects: Enhancing Physical Health and Reducing Depression in Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

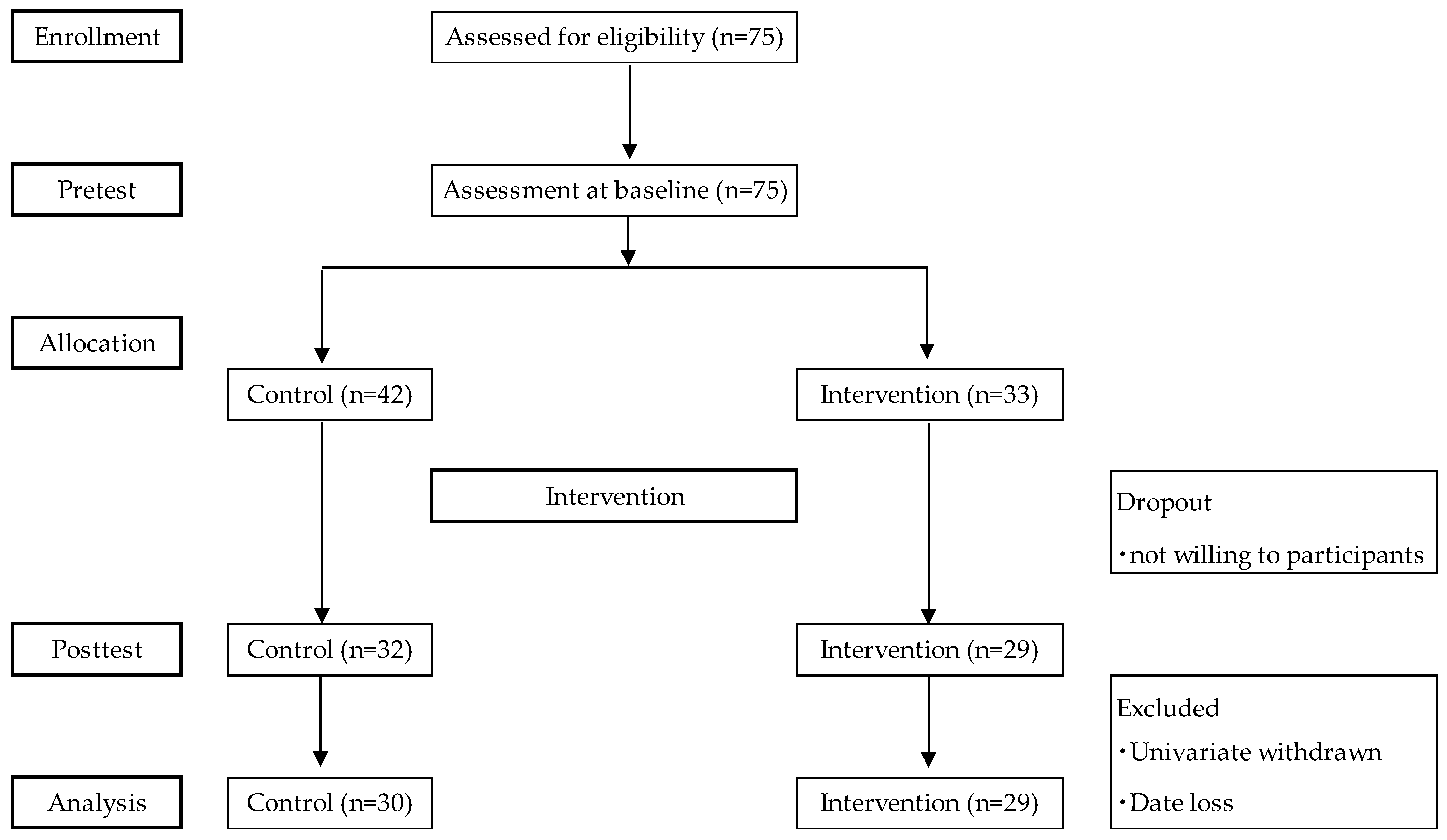

2.1. Participants

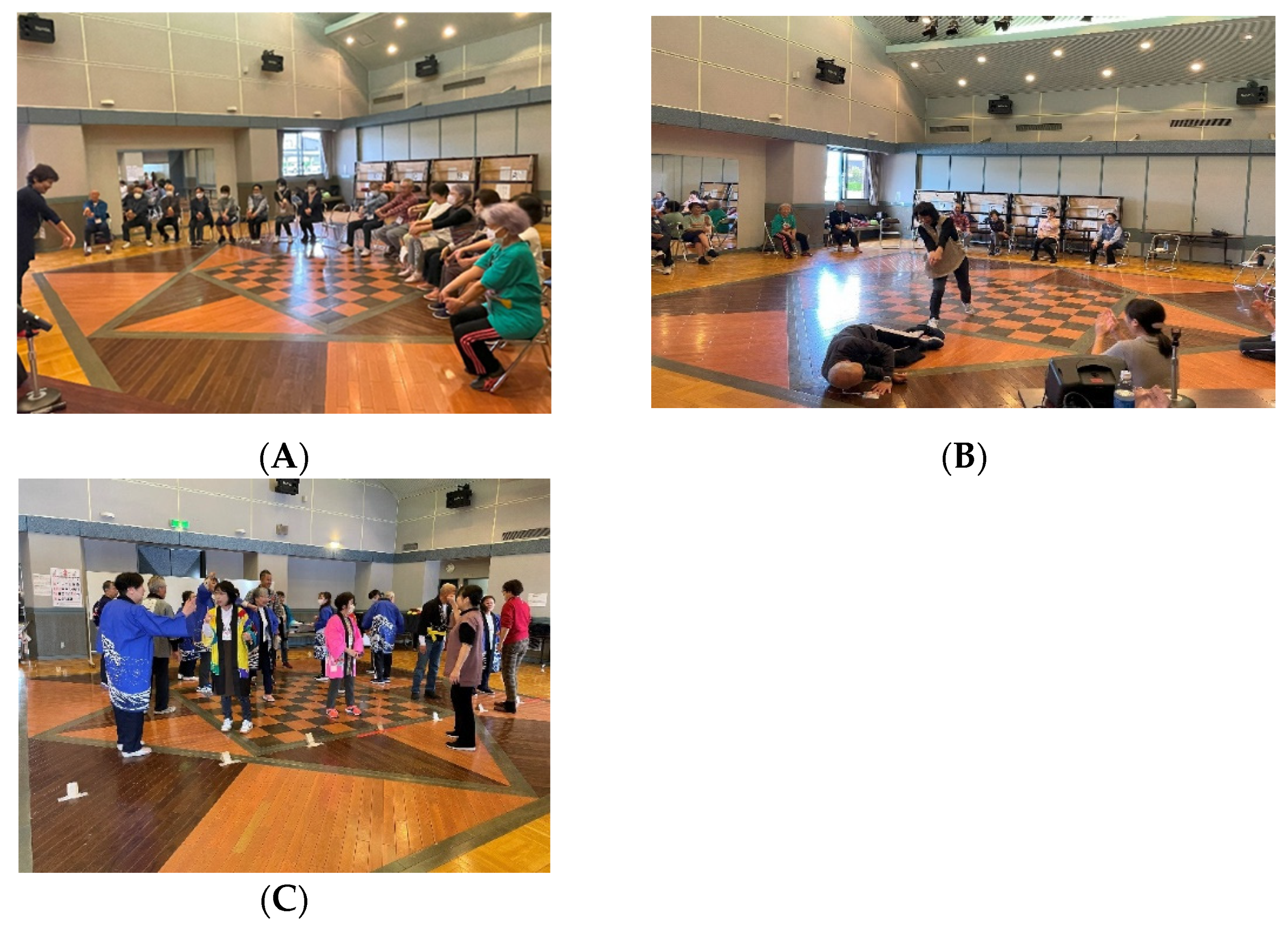

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Outcome

2.3.1. Components of NCGG-FAT

2.3.2. Tablet Version of Word Recognition (WR)

2.3.3. Tablet Version of Trail Making Test Version A (TMT-A) and Version B (TMT-B)

2.3.4. Tablet Version of Symbol Digit Substitution Task (SDST)

2.3.5. Criteria of Physical Frailty

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, Q.L. The frailty syndrome: Definition and natural history. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2011, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walston, J.; Hadley, E.C.; Ferrucci, L. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: Toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: Summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, F.; Eichler, H.G.; Rasi, G. Drug policy for an aging population—The European Medicines Agency’s geriatric medicines strategy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1972–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Liu, W.; Gao, Y.; Qin, L.; Feng, H.; Tan, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, L.; Wu, I.X.Y. Comparative effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for frailty: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, E.F.; Schechtman, K.B.; Ehsani, A.A.; Steger-May, K.; Brown, M.; Sinacore, D.R.; Yarasheski, K.E.; Holloszy, J.O. Effects of exercise training on frailty in community-dwelling older adults: Results of a randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 1921–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S.H.; Travers, J.; Shé, É.N.; Bailey, J.; Romero-Ortuno, R.; Keyes, M.; O’Shea, D.; Cooney, M.T. Primary care interventions to address physical frailty among community-dwelling adults aged 60 years or older: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeyne, L.; Deschodt, M.; Verschueren, S.; Tournoy, J.; Gielen, E. Effects of multi-domain interventions in (pre)frail elderly on frailty, functional, and cognitive status: A systematic review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noice, H.; Noice, T. Long-term retention of theatrical roles. Memory 1999, 7, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noice, H.; Noice, T.; Staines, G. A short-term intervention to enhance cognitive and affective functioning in older adults. J. Aging Health 2004, 16, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noice, T.; Noice, H.; Kramer, A.F. Participatory arts for older adults: A review of benefits and challenges. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noice, H.; Noice, T. A Theatrical Intervention to Improve Cognition in Intact Residents of Long Term Care Facilities. Clin. Gerontol. 2006, 29, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, G.; Yin, H.; Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Shang, B.; Wang, C.; Chen, L. Effects of dance intervention on frailty among older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 88, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y.; Arenaza-Urquiljo, E.M.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Belleville, S.; Cantillon, M.; Chetelat, G.; Ewers, M.; Franzmeier, N.; Kempermann, G.; Kremen, W.S.; et al. Whitepaper: Defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, S1552–S5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raz, N.; Kennedy, K.M. A systems approach to the aging brain: Neuroanatomic changes, their modifiers and cognitive correlates. In Imaging the Aging Brain; Jagust, W., D’Esposito, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, G.D. Physical activity and coronary heart disease in older adults: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Eur. J. Public Health 2002, 12, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venjatraman, J.T.; Fernandes, G. Exercise, immunity and aging. Aging Milano 1997, 9, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ewan, T.; Giuseppe, B.; Antonino, P.; Jessica, B.; Vincenza, L.; Antonio, P.; Marianna, B. Physical activity programs for balance and fall prevention in elderly A systematic review. Medicine 2019, 98, e16218. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, G.; Perlstein, S.; Chapline, J.; Kelly, J.; Firth, K.; Simmens, S. The Impact of Professionally Conducted Cultural Programs on the Physical Health, Mental Health, and Social Functioning of Older Adults. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, A.; Kume, Y.; Watanabe, N.; Iino, Y.; Imamura, S.; Ota, H. Effectiveness of a Theater Program Intervention on the Cognitive, Physical, and Social Functions of Elderly People Living in the Community: A Pilot Survey. Clin. Case Rep. Int. 2023, 7, 1591. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power ana lyses using g*power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satake, S.; Senda, K.; Hong, Y.; Miura, H.; Endo, H.; Sakurai, T.; Kondo, I.; Toba, K. Validity of the Kihon Checklist for assessing frailty status. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, J.; Yesavage, J. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Ment. Health 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Park, H.; Doi, T.; Yoshida, D.; Uemura, K.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Suzuki, T. Evaluation of multidimensional neurocognitive function using a tablet personal computer: Test-retest reliability and validity in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2013, 13, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satake, S.; Arai, H. The revised Japanese version of the Cardiovascular Health Study criteria (revised J-CHS criteria). Geriatr. Gerontol. 2020, 20, 992–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haekkinen, K. Ageing and neuromuscular adaptation to strength training. In Strength and Power in Sport, 2nd ed.; Komi, P.V., Ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 409–425. [Google Scholar]

- Noice, H.; Noice, T. Learning dialogue with and without movement. Mem. Cogn. 2001, 29, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, S.T.; Horwitz, B.N. Positive emotions and health: What we know about aging. In Successful Cognitive and Emotional Aging; Depp, C.A., Jeste, D.V., Eds.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lorek, A.E.; Dattilo, J.; Mogle, J.; Freed, S.; Frysinger, M.; Chen, S.T. Staying connected: Recommendations by older adults concerning community leisure service delivery. J. Park Recreat. Admi. 2017, 35, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalan-Matamoros, D.; Gomez-Conesa, A.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D. Exercise improves depressive symptoms in older adults: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 244, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Silva, E.S.; Hallgren, M.; De Leon, A.P.; Dunn, A.L.; Deslandes, A.C.; et al. Physical activity and incident depression: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morres, I.D.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Stathi, A.; Comoutos, N.; Arpin-Cribbie, C.; Krommidas, C.; Theodorakis, Y. Aerobic exercise for adult patients with major depressive disorder in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, N.T.; Marshall, A.; Roberts, C.H.; Demakakos, P.; Steptoe, A.; Scholes, S. Physical activity and trajectories of frailty among older adults: Evidence from the English longitudinal study of aging. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantoja-Cardoso, A.; Aragão-Santos, J.C.; Santos, P.d.J.; Dos-Santos, A.C.; Silva, S.R.; Lima, N.B.C.; Vasconcelos, A.B.S.; Fortes, L.d.S.; Da Silva-Grigoletto, M.E. Functional Training and Dual-Task Training Improve the Executive Function of Older Women. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollesen, B.; Wildbredt, A.; van Schooten, K.S. The effects of cognitive-motor training interventions on executive functions in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control Group | Intervention Group | p Value | Effect Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 30 | n = 29 | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age (years) | 75.6 | 5.5 | 73.1 | 5.8 | 0.061 | −0.498 |

| Gender (%female) | 63.30 | 72.40 | 0.456 | 0.611 | ||

| Height (cm) | 156.3 | 6.8 | 155.6 | 6.5 | 0.664 | −0.114 |

| Weight (kg) | 56.9 | 9.2 | 56.3 | 9.5 | 0.864 | −0.045 |

| Medication (n) | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 0.198 | 0.068 |

| Education (years) | 12.7 | 2.3 | 13.2 | 2.4 | 0.439 | 0.186 |

| KCL (point) | 4.5 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 0.647 | 0.120 |

| Control Group (n = 30) | Intervention Group (n = 29) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | Interaction (Group × Time) | Main Effect (Group) | Main Effect (Time) | |||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value | F (5.76) | p Value | η2 | F (5.76) | p Value | η2 | F (5.76) | p Value | η2 | |

| GS (kg) | 26.0 | 7.9 | 26.3 | 7.3 | 0.526 | 25.2 | 1.3 | 26.6 | 1.4 | 0.009 ** | 0.778 | 0.382 | 0.013 | 0.047 | 0.830 | 0.001 | 9.206 | 0.004 | 0.139 |

| UWS (m/s) | 1.34 | 0.05 | 1.36 | 0.07 | 0.532 | 1.24 | 0.37 | 1.46 | 0.34 | 0.000 ** | 9.024 | 0.004 ** | 0.137 | 0.048 | 0.828 | 0.001 | 20.723 | 0.000** | 0.267 |

| WM (point) | 13.6 | 0.6 | 12.8 | 0.8 | 0.153 | 14.4 | 0.5 | 15.0 | 0.5 | 0.282 | 2.735 | 0.104 | 0.046 | 2.870 | 0.096 | 0.048 | 0.016 | 0.901 | 0.000 |

| TMT-A (s) | 20.9 | 1.3 | 20.6 | 0.9 | 0.725 | 18.8 | 0.9 | 18.8 | 0.9 | 0.966 | 0.060 | 0.808 | 0.001 | 1.664 | 0.202 | 0.028 | 0.060 | 0.808 | 0.001 |

| TMT-B (s) | 40.8 | 4.4 | 41.9 | 4.0 | 0.738 | 32.1 | 2.4 | 28.6 | 1.8 | 0.099 | 0.412 | 0.524 | 0.027 | 6.003 | 0.017 * | 0.095 | 0.412 | 0.524 | 0.007 |

| SDST (point) | 46.5 | 1.9 | 46.3 | 2.2 | 0.757 | 52.9 | 2.0 | 54.8 | 2.6 | 0.163 | 1.599 | 0.211 | 0.027 | 5.669 | 0.021 * | 0.090 | 1.491 | 0.227 | 0.025 |

| GDS-15 (point) | 3.0 | 0.5 | 5.1 | 0.7 | 0.002 ** | 2.8 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.012 * | 17.565 | 0.000 ** | 0.236 | 5.034 | 0.029 * | 0.081 | 2.704 | 0.106 | 0.045 |

| Control Group | p Value | Effect Size | Intervention Group | p Value | Effect Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | |||||

| physical frailty (%) | 0.723 | 0.323 | 0.018 * | 0.417 | ||||

| robust | 56.7 | 46.7 | 48.3 | 82.8 | ||||

| pre-frailty | 36.7 | 46.7 | 51.7 | 17.2 | ||||

| frailty | 6.7 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kodama, A.; Watanabe, N.; Ozawa, H.; Imamura, S.; Umetsu, Y.; Sato, M.; Ota, H. Senior Theater Projects: Enhancing Physical Health and Reducing Depression in Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101289

Kodama A, Watanabe N, Ozawa H, Imamura S, Umetsu Y, Sato M, Ota H. Senior Theater Projects: Enhancing Physical Health and Reducing Depression in Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(10):1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101289

Chicago/Turabian StyleKodama, Ayuto, Nobuko Watanabe, Hitomi Ozawa, Shinsuke Imamura, Yoko Umetsu, Manabu Sato, and Hidetaka Ota. 2024. "Senior Theater Projects: Enhancing Physical Health and Reducing Depression in Older Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 10: 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101289

APA StyleKodama, A., Watanabe, N., Ozawa, H., Imamura, S., Umetsu, Y., Sato, M., & Ota, H. (2024). Senior Theater Projects: Enhancing Physical Health and Reducing Depression in Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(10), 1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101289