Assessment of the Mental Health of Police Officers: A Systematic Review of Specific Instruments

Abstract

1. Introduction

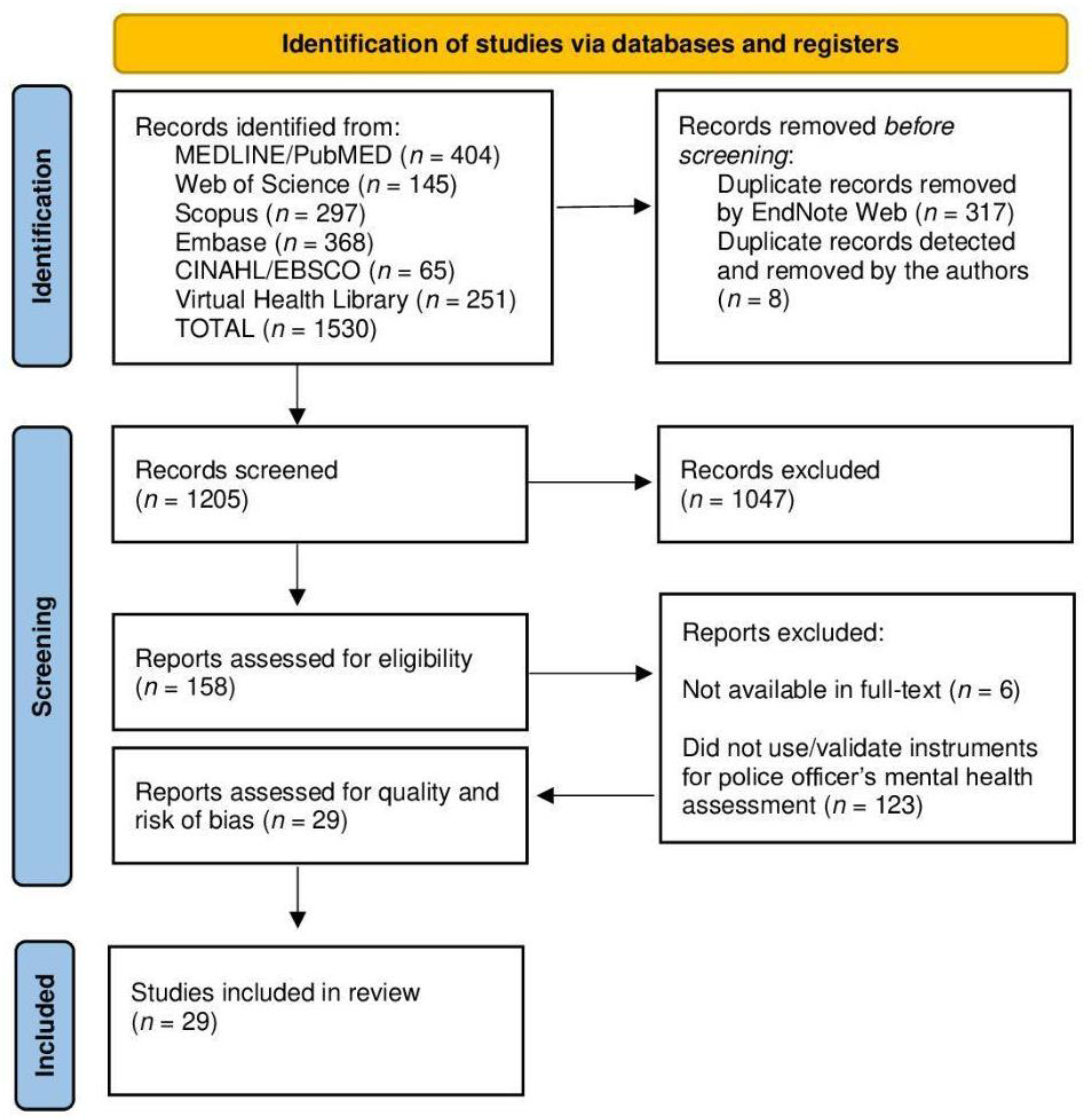

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening and Quality Appraisal

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Characterization of the Instruments Identified in the Review

3.4. Psychometric Properties of the Instruments Identified in the Review

3.5. Work-Related Stress Instruments

3.6. Burnout Instruments

3.7. Coping and Satisfaction with Work Instruments

3.8. Risk of Psychological Distress Instruments

3.9. Mental Health Disorders Instruments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sampaio, F.; Coelho, J.; Gonçalves, P.; Sequeira, C. Protective and Vulnerability Factors of Municipal Workers’ Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Envion. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demou, E.; Hale, H.; Hunt, K. Understanding the mental health and wellbeing needs of police officers and staff in Scotland. Police Pract. Res. 2020, 21, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queirós, C.; Passos, F.; Bártolo, A.; Marques, A.J.; Silva, C.F.; Pereira, A. Burnout and Stress Measurement in Police Officers: Literature Review and a Study With the Operational Police Stress Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, P.; Mnatsakanova, A.; McCanlies, E.; Fekedulegn, D.; Hartley, T.A.; Andrew, M.E.; Violanti, J.M. Police stress and depressive symptoms: Role of coping and hardiness. Polic. Int. J. 2019, 43, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, M.S.; Gilbert, A.R.; Swartz, M.S. Police Mental Health: A Neglected Element of Police Reform. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Ashwick, R.; Schlosser, M.; Jones, R.; Rowe, S.; Billings, J. Global prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in police personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Envion. Med. 2020, 77, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, R.; Johnston, M.S. Police Mental Health and Wellness. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, P.; Porter, C.N. Understanding the impact of organizational and operational stressors on the mental health of police officers in Ireland. Police Pract. Res. 2024, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, L.; Hegarty, S.; Vallières, F.; Hyland, P.; Murphy, J.; Fitzgerald, G.; Reid, T. Identifying the Key Risk Factors for Adverse Psychological Outcomes Among Police Officers: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Trauma. Stress 2019, 32, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gouveia, A.O.; Dias, A.S.; do Carmo Mercedes, B.P.; da Costa Salvador, J.; da Silva Junior JC, P.; Peixoto, L.G.; de Moraes RC, L. Detecção Precoce dos Sintomas Depressivos pela Equipe de Saúde na Atenção Básica na Região Norte do País: Revisão De Literatura. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 38093–38103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.E.; Milligan-Saville, J.; Petrie, K.; Bryant, R.A.; Mitchell, P.B.; Harvey, S.B. Mental health screening amongst police officers: Factors associated with under-reporting of symptoms. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koedijk, M.; Renden, P.G.; Oudejans, R.R.D.; Kleygrewe, L.; Hutter, R.I.V. Observational Behavior Assessment for Psychological Competencies in Police Officers: A Proposed Methodology for Instrument Development. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 589258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewin, C.; Miller, J.; Soffia, M.; Peart, A.; Burchell, B. Posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in UK police officers. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI 2020, 1, 1–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, W.C.O. Recuperação da informação em saúde. ConCI 2020, 3, 100–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovito, M.J.; Bruzzone, A.; Lee, E.; López Castillo, H.; Talton, W.; Taliaferro, L.; Falk, D. Assessing Health-Related Quality of Life Among Survivors of Testicular Cancer: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Men’s Health 2021, 15, 1557988320982184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Franciscus, G.; Swartbooi, C.; Munnik, E.; Jacobs, W. The SFS scoring system. In Symposium on Methodological Rigour and Coherence: Deconstructing the Quality Appraisal Tool in Systematic Review Methodology, Proceedings of the 21st National Conference of the Psychological Association of South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa, 15–18 September 2015; Smith, M.R., Ed.; Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC193860 (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Orth, Z.; Van Wyk, B. Measuring mental wellness among adolescents living with a physical chronic condition: A systematic review of the mental health and mental well-being instruments. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and extensions: A scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, D.A.; Varetto, A.; Zedda, M.; Ieraci, V. Occupational stress, anxiety and coping strategies in police officers. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.M.; Hem, E.; Lau, B.; Ekeberg, Ø. An exploration of job stress and health in the Norwegian police service: A cross sectional study. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2006, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.M.; Hem, E.; Lau, B.; Håseth, K.; Ekeberg, Ø. Stress in the Norwegian police service. Occup. Med. 2005, 55, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Mason, J.E.; Ricciardelli, R.; McCreary, D.R.; Vaughan, A.D.; Anderson, G.S.; Krakauer, R.L.; et al. Assessing the Relative Impact of Diverse Stressors among Public Safety Personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Vargas-Roman, K.; Fuente, G.R.C.D.; Tania, A.C.; Aguayo-Extremera, R.; Albendín-García, L. Study of the Predictive Validity of the Burnout Granada Questionnaire in Police Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo-Ferraz, H.; Gil-Monte, P.R.; Queirós, C.; Passos, F. Validação Fatorial do “Spanish Burnout Inventory” em Policiais Portugueses. Psicol. Reflexão E Crítica 2014, 27, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rivera, B.R.; Olguín-Tiznado, J.E.; Aranibar, M.F.; Ramírez-Barón, M.C.; Camargo-Wilson, C.; López-Barreras, J.Á.; García-Alcaraz, J.L. Burnout Syndrome in Police Officers and Its Relationship with Physical and Leisure Activities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harizanova, S.N.; Mateva, N.G.; Tarnovska, T.C. Adaptation and Validation of a Burnout Inventory in a Survey of the Staff of a Correctional Institution in Bulgaria. Folia Med. 2016, 58, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelaš, I.G.; Dević, I.; Karlović, R. Socijalna podrška, tress, izgaranje I zdravlje kod policijskih službenika. Sigur. Časopis Za Sigur. U Radn. I Zivotn. Okolini. 2020, 62, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniper, B.; White, N.; Bellamy, P. A new approach to evaluating the well-being of police. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luceño-Moreno, L.; Talavera-Velasco, B.; Jaén-Díaz, M.; Martín-García, J. Occupational Stress in Spanish Police Officers: Validating the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, M.K. Gender Differences in Perceived Role Expectations, Mental Health, and Job Satisfaction of Civil Police Constables: A Quali-Quantitative Survey. Orient. Anthropol. 2019, 19, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Abidin, E.Z.; Rasdi, I.; Ismail, Z.S. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Malaysian Police Officers Mental Health: Depression, Anxiety and Stress. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 116, S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, C.; Passos, F.; Bártolo, A.; Faria, S.; Fonseca, S.M.; Marques, A.J.; Silva, C.F.; Pereira, A. Job Stress, Burnout and Coping in Police Officers: Relationships and Psychometric Properties of the Organizational Police Stress Questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talavera-Velasco, B.; Luceño-Moreno, L.; Martín García, J.; Vázquez-Estévez, D. DECORE-21: Assessment of occupational stress in police. Confirmatory factor analysis of the original model. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hasselt, V.B.; Sheehan, D.C.; Sellers, A.H.; Baker, M.T.; Feiner, C.-A. A Behavioral-Analytic Model for Assessing Stress in Police Officers: Phase I. Development of the Law Enforcement Officer Stress Survey (LEOSS). Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 2009, 5, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Winwood, P.C.; Tuckey, M.R.; Peters, R.; Dollard, M.F. Identification and measurement of work-related psychological injury: Piloting the psychological injury risk indicator among frontline police. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, R.; Willemin-Petignat, L.; Rolli Salathé, C.; Samson, A.C.; Putois, B. Profiling Police Forces against Stress: Risk and Protective Factors for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Burnout in Police Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, K.L.; Jamshidi, L.; Nisbet, J.; Teckchandani, T.A.; Price, J.A.B.; Ricciardelli, R.; Anderson, G.S.; Carleton, R.N. Exposures to Potentially Psychologically Traumatic Events among Canadian Coast Guard and Conservation and Protection Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshai, S.; Mishra, S.; Feeney, J.R.; Summerfield, T.; Hembroff, C.C.; Krätzig, G.P. Resilience in the Ranks: Trait Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Buffer the Deleterious Effects of Envy on Mental Health Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Edgar, N.E.; MacLean, S.E.; Hatcher, S. Workplace Assessment Scale: Pilot Validation Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeganish, A.; Kiran, P.R.; Lyngdoh, D.R.; Abhay, J.; Anand, R.; Goalla, P.C.; Gnanaselvam, N.A. Health status of police personnel in a selected subdivision of Bengaluru District, Karnataka, India. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health 2024, 14, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyron, M.J.; Rikkers, W.; Bartlett, J.; Renehan, E.; Hafekost, K.; Baigent, M.; Cunneen, R.; Lawrence, D. Mental health and wellbeing of Australian police and emergency services employees. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 77, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Han, S. Factors affecting post-traumatic growth in South Korean police officers by age group. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health 2022, 12, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Gu, X.; He, J.; Jiao, Y.; Xia, F.; Feng, Z. Development and validation of police mental health ability scale. J. Occup. Health 2022, 64, e12366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlendorf, D.; Schlenke, J.; Nazzal, Y.; Dogru, F.; Karassavidis, I.; Holzgreve, F. Musculoskeletal complaints, postural patterns and psychosocial workplace predictors in police officers from an organizational unit of a German federal state police force—A study protocol. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2023, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohwer, E.; Velasco Garrido, M.; Herold, R.; Preisser, A.M.; Terschüren, C.; Harth, V.; Mache, S. Police officers’ work-life balance, job satisfaction and quality of life: Longitudinal effects after changing the shift schedule. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e63302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, J.P.; Mendonça, V.G.; Vieira, L.S.; Guimarães, R.S.W.; Magnago, T.S.B.S.; Machado, W.D.L.; Pai, D.D. Minor psychiatric disorders and the work context of Civil Police: A mixed method study. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2022, 71, 2288–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Q.; Xia, M.; Xiao, J.; Yan, X.; Li, D. A study on mental health and its influencing factors among police officers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 119257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, J.; Peña, M.; Topa, G. Lack of group support and burnout syndrome in workers of the state security forces and corps: Moderating role of neuroticism. Medicina 2019, 55, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenheim, M.; Bastos, J.L. What, what for and how? Developing measurement instruments in epidemiology. Rev. Saúde Pública 2021, 55, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, R. Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security. In Proceedings of the Healthy Minds, Safe Communities: Supporting Our Public Safety Officers through a National Strategy for Operational Stress Injuries, House of Commons, Ottawa, ON, Canada, October 2016; p. 39. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.825367/publication.html (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Shuttleworth, M. Internal Consistency Reliability. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Research Design; Michalosv, A.C., Ed.; University of Northern British Columbia: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2022; pp. 3305–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmi, P.; Colledani, D.; Robusto, E. A Comparison of Classical and Modern Measures of Internal Consistency. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keszei, A.P.; Novak, M.; Streiner, D.L. Introduction to health measurement scales. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmond, S.S. Evaluating the Reliability and Validity of Measurement Instruments. Orthop. Nurs. 2008, 27, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo-Arias, A.; Pineda-Roa, C.A. Instrument Validation Is a Necessary, Comprehensive, and Permanent Process. Alpha Psychiatry 2022, 23, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; Aung, M.M.T.; Oo, S.S.; Abas, M.I.; Kamudin, N.A.F. Content validation template (CVT). J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2022, 93, 1151–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizumic, B.; Gunningham, B.; Christensen, B.K. Prejudice towards people with mental illness, schizophrenia, and depression among mental health professionals and the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burzee, Z.; Bowers, C.; Beidel, D. A re-evaluation of Stuart’s police officer stigma scale: Measuring mental health stigma in first responders. Frontiers in Public Health. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 951347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaytor, N.; Barbosa-Leiker, C.; Germine, L.; Fonseca, L.; McPherson, S.; Tuttle, K. Construct validity, ecological validity and acceptance of self-administered online neuropsychological assessment in adults. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 35, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, L.; Héron, M.; Aubert, L.; Motreff, Y.; Pirard, P.; Paranhos, M.; Corte, F.; Vuillermoz, C.; Vandentorren, S.; Aarbaoui, T. Evaluation of the self-reported questionnaires used to assess mental health after the January 2015 terrorist attacks in the Paris Region: IMPACTS survey. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 65, S262–S263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H. How short or long should be a questionnaire for any research? Researchers dilemma in deciding the appropriate questionnaire length. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2022, 16, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, G.; Vachon, H.; Lafit, G.; Kuppens, P.; Houben, M.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Viechtbauer, W. The effects of sampling frequency and questionnaire length on perceived burden, compliance, and careless responding in experience sampling data in a student population. Assessment 2022, 29, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselhorn, K.; Ottenstein, C.; Meiser, T.; Lischetzke, T. The Effects of Questionnaire Length on the Relative Impact of Response Styles in Ambulatory Assessment. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2024, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogan, W. Why study policing comparatively? Polic. Soc. 2022, 32, 254–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, R. “Risk It Out, Risk It Out”: Occupational and Organizational Stresses in Rural Policing. Police Q. 2018, 21, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, H.; Mazerolle, L.; Possingham, H.; Tam, K.; Biggs, D. A methodological guide for translating study instruments in cross-cultural research: Adapting the ‘connectedness to nature’ scale into Chinese. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategies |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE/PubMed | ((Police) AND (Mental health)) AND (Surveys and Questionnaires) |

| Web of Science | ((ALL = (Police)) AND ALL = (Mental health)) AND ALL = (Surveys and Questionnaires) |

| Scopus | ((police) AND (mental AND health) AND (surveys AND questionnaires)) |

| Embase | ‘police’ AND ‘mental health’ AND ‘surveys and questionnaires’ |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | police AND mental health AND (surveys and questionnaires) |

| Virtual Health Library (VHL) | “Police” AND “Mental health” AND “Surveys and Questionnaires” |

| Code/Reference | Origin | Study Design | Sample Description | Sample Size (n) | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 Maran et al. 2015 [21] | Italy | Cross-sectional | Unit managers, non-commissioned officers, emergency officers, and traffic patrol officers | 617 | Brief COPE; Police Stress Questionnaire-Operational and Organizational (PSQ-OP and PSQ-Org) |

| S2 Berg et al. 2006 [22] | Norway | Cross-sectional | Investigation police, uniformed officers, and administration officers | 3272 | Norwegian Police Stress Survey (NPSS); Job Stress Survey (JSS); Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) |

| S3 Berg et al. 2005 [23] | Norway | Methodological instrument creation | Police officers | 3272 | Job Stress Survey (JSS) and Norwegian Police Stress Survey (NPSS) |

| S4 Carleton et al. 2020 [24] | Canada | Cross-sectional | Correctional officers, federal police, municipal/provincial police, public safety communications officials | 3118 | PSQ-Op; PSQ-Org and Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) |

| S5 Fuente-Solana et al. 2020 [25] | Spain | Methodological instrument validation | Officers, middle managers, and managers | 1884 | Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI); Granada Burnout Questionnaire (GBQ) |

| S6 Figueiredo-Ferraz et al. 2014 [26] | Portugal | Methodological instrument validation | Public safety police | 245 | Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI) |

| S7 García-Rivera et al. 2020 [27] | Mexico | Cross-sectional | Preventive police officers | 276 | Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI) and PSQ-Op |

| S8 Harizanova et al. 2016 [28] | Bulgaria | Methodological instrument validation | Correctional Officers | 50 | V. Bokyo Burnout Inventory (VBBI) |

| S9 Jelaš et al. 2020 [29] | Trinidad and Tobago | Cross-sectional | Police officers | 331 | MBI; PSQ-Op; PSQ-Org |

| S10 Juniper et al. 2010 [30] | United Kingdom | Methodological instrument creation | Officers, police community support officers, and civilian staff | 822 | Work and well-being assessment for police (WWBAP) |

| S11 Luceño-Moreno et al. 2021 [31] | Spain | Methodological instrument validation | Patrol officers, corporals, non-commissioned officers, police commissioner officers | 217 | Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERIQ); DECORE-21; MBI |

| S12 Maurya, 2019 [32] | India | Mixed methods | Civil police | 203 | Police role expectations (PRE) |

| S13 Mohamed et al. 2022 [33] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | Police officers | 1641 | PSQ-Op and PSQ-Org |

| S14 Queirós et al. 2020 [34] | Portugal | Cross-sectional | National police | 1131 | PSQ-OP; PSQ-Org; Brief COPE and SBI |

| S15 Talavera-Velasco et al. 2018 [35] | Spain | Methodological instrument validation | Local police officers | 223 | DECORE-21 |

| S16 Van Hasselt et al. 2003 [36] | United States of America (USA) | Methodological instrument creation | Detectives, traffic officers, SWAT | 166 | Law Enforcement Officer Stress Survey (LEOSS) |

| S17 Winwood et al. 2009 [37] | United States of America (USA) | Methodological instrument creation | Frontline police officers | 217 | Psychological Injury Risk Indicator (PIRI) |

| S18 Anders et al. 2022 [38] | Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Emergency police, judicial police, community police, administrative, traffic, special forces, and dispatch center | 1073 | The Impact of Event Scale—Revised (TIES-r); MBI; Brief COPE, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and suicide ideation from the Beck Depression Inventory—II (SI-BDI-II). |

| S19 Andrews et al. 2022 [39] | Canada | Cross-sectional | Coast Guard and Conservation Officers | 412 | General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) |

| S20 Beshai et al. 2022 [40] | Canada | Cross-sectional | Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 173 | Job Descriptive Index (JDI); PHQ-9; GAD-7; Brief Resilience Scale (BRS); Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) |

| S21 Huang et al. 2022 [41] | Canada | Methodological instrument validation | Police officers | 22 | MBI; PHQ-9; GAD-7; BRS; PSS |

| S22 Jeganish et al. 2024 [42] | India | Cross-sectional | State police | 142 | PHQ-9 and PSS |

| S23 Kyron et al. 2022 [43] | Australia | Cross-sectional | Police officers | 8088 | BRS |

| S24 Lee; Hans, 2022 [44] | South Korea | Cross-sectional | Police officers | 269 | TIES-r |

| S25 Liao et al. 2022 [45] | China | Methodological instrument validation | Police officers | 767 | Police Mental Health Ability (PMHA) |

| S26 Ohlendorf et al. 2023 [46] | Germany | Cross-sectional | Federal police | 200 | Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) and PSQ-Op |

| S27 Rohwer et al. 2022 [47] | Germany | Cohort | Police officers | 116 | Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) |

| S28 Tavares et al. 2022 [48] | Brazil | Mixed methods | Civil Police | 237 | Self-Reported Questionnaire-20 (SRQ-20) |

| S29 Wu et al. 2023 [49] | China | Cross-sectional | Security police, criminal police, constable police, community police, and internal work police | 358 | Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) |

| Instrument | Outcomes | Subscales/Domains | Items | Cutoff Values | Used in | Police Specific? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) | Burnout. | Emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement. | 22 | None. | S2, S5, S9, S11, S18, and S21 | No |

| Granada Burnout Questionnaire (GBQ) | Burnout. | Emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement. | 26 | None. | S5 | No |

| Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI) | Burnout. | Enthusiasm for work, psychic wear, indolence, and guilt. | 20 | Low scores on enthusiasm for work and high scores on psychic exhaustion and indolence represent high levels of burnout syndrome. | S6, S7, and S14 | No |

| V. Bokyo Burnout Inventory (VBBI) | Burnout. | Stress, resistibility, and exhaustion. | 84 | Scoring is carried out in two stages. The first evaluates each symptom: <9 (symptom is not important), 10–15 (symptom settling in), and >16 (active symptom). After the sum of the symptoms, there are scores for each of the three phases, where <36 = the phase is not developed, 37–60 = in the process of development, and >61 = the phase is developed. | S8 | No |

| The Job Stress Survey (JSS) | Occupational stress. | Pressure at work, lack of support. | 30 | Each stressor is evaluated on a Likert scale from 0 to 9+ points by frequency of occurrence in the last six months. The sum is the result of the scale. | S2 and S3 | No |

| The Norwegian Police Stress Survey (NPSS) | Occupational stress. | Job pressure, lack of support, serious operational tasks, and work injuries. | 36 | None. | S2 and S3 | Yes |

| Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERIQ) | Occupational stress. | Effort, reward (esteem, financial, status, and job security), and overcommitment. | 23 | Effort score from 6 to 30; reward from 11 to 55; overcommitment score from 6 to 30. The effort and overcommitment scores are added together, which indicate imbalance and occupational stress if they are higher than the reward score | S11 | No |

| Law Enforcement Officer Stress Survey (LEOSS) | Occupational stress. | None. | 25 | None. | S16 | Yes |

| Operational Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ-OP) | Occupational stress. | None. | 20 | The higher the score, the greater the stress. | S1, S4, S7, S9, S13, S14, S18, and S26 | Yes |

| Organizational Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ-Org) | Occupational stress. | None. | 20 | The higher the score, the greater the stress. | S1, S4, S9, S13, S14, and S18 | Yes |

| Work and Well-Being Assessment for Police (WWBAP) | Work-related well-being. | Advancement, home work interface, job, organizational, physical, psychological, relationships, workload, and facilities. | 46 | The higher the score, the lower the well-being. | S10 | Yes |

| Police Role Expectations (PRE) | Expectations regarding the job. | Aggressiveness, facilitative, conformist, and authoritative. | 18 | The score from 18 to 90, the higher the score, the higher the job expectation. | S12 | Yes |

| Psychological Injury Risk Indicator (PIRI) | Risk of psychological injury. | Turbulent sleep/poor sleep hygiene, maladaptive experience, chronic fatigue, consistent failure to recover physical and emotional energy, PTSD symptomatology, and alcohol abuse/self-medication related to stress. | 30 | A standardized PIRI score of more than 25 corresponded to possible psychological injury, while higher scores indicate a greater risk of injury. | S17 | Yes |

| DECORE-21 | Risk of psychological injury. | Cognitive demands, control, work organization support, and rewards. | 21 | The higher the score, the greater the psychological risk suffered at work. | S11 and S15 | No |

| Brief COPE | Coping strategies. | Acceptance, active coping, guilt, behavioral withdrawal, denial, distraction, emotional expression, emotional support, humor, instrumental support, planning, positive reinterpretation, religion, and substance use. | 28 | On a four-point Likert scale, ranging from zero points to three points depending on the answer; higher scores reflect a higher tendency to implement corresponding coping strategies. | S1, S14, and S18 | No |

| The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Anxiety and depression. | Anxiety and depression. | 14 | The typical clinical threshold for the presence of anxiety is a score ≥ 8 and similarly for depression and a total score ≥ 11 may reflect an adjustment disorder in general, although due to anxiety or depression. | S18 | No |

| Suicide ideation from Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-II) | Suicide risk. | None. | 1 | Arranged on a 4-point Likert scale as follows: 0 (“I have no thoughts of killing myself”), 1 (“I have thoughts of killing myself, but I wouldn’t do it”), 2 (“I would like to kill myself”), and 3 (“I would kill myself if I had the chance”). | S18 | No |

| Abridged Job Descriptive Index (JDI) | Overall job satisfaction. | Job, compensation, promotion, supervision, and co-workers. | 8 | None. | S20 | No |

| The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | Depression. | None. | 8 | It is organized on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = almost every day). Cutoff is a PHQ-9 score > or = 10. | S19–S22 | No. |

| The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) | Anxiety. | None. | 7 | It is organized on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never to 3 = almost every day). Cutoff is a PHQ-9 score > or = 10. | S19–S21 | No |

| The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | Resilience and ability to recover from adversity. | None. | 6 | Organized in a 5-point Likert scale to assess the extent to which the interviewed agreed to give a statement, in which 1 means completely disagree and 5 means completely agree. | S20, S21, and S23 | No |

| The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | Stress. | None. | 10 | It is organized in a Cohen scale (0, never; 1, almost never; 2, sometimes; 3, quite often; 4, very often) to score the scale, A high score indicates a high perception of stress. | S4, S20–S22 | No. |

| Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) | Minor psychiatric disorders. | Anxious and depressed mood, somatic mood, decreased energy, and depressive thoughts. | 20 | If the values are equal to or greater than 7 points, or a greater proportion of positive responses in both sexes, based on a study with police officers, then this indicates minor psychological problems. | S28 | No. |

| Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) | Psychological suffering and symptoms of psychopathology. | Somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychosis. | 90 | If the number of positive numbers is superior to 43 points or the total score is superior to 160. | S29 | No. |

| Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) | Job satisfaction. | None. | 7 | Arranged on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = very satisfied to 4 = very unhappy. The cutoff points vary from 0 (lowest job satisfaction) to 100 (highest job satisfaction. | S26 and S27 | No. |

| Police mental health ability (PMHA) | Occupational stress. | Cognitive intelligence, emotional catharsis, quick determination, behavioral impulse, and search for rewards. | 20 | It works with a “yes” or “no” response. The cutoff values are not mentioned. | S26 | Yes. |

| The Impact of Event Scale—Revised (TIES-r) | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. | Intrusion, avoidance, and hypervigilance. | 22 | A 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). The sum of the three subscale scores determines a composite PTSD score for which the typical clinical threshold for the presence of PTSD is a score ≥ 33. | S18 and S24 | No |

| Instrument | Cronbach’s Alpha | Test–Retest | Item-item Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brief COPE | 0.85 | 0.71 | |

| Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) | 0.8 | 0.69 | |

| Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) | 0.82 | ||

| DECORE-21 | In subscales: 0.6 in cognitive demands, 0.78 in control, 0.84 in organizational support, and 0.92 in rewards. | ||

| Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERIQ) | In subscales: effort with 0.78, reward with 0.91, and overcommitment with 0.81. | ||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.65 |

| Granada Burnout Questionnaire (GBQ) | In subscales: emotional exhaustion = 0.87, depersonalization = 0.85, and personal accomplishment = 0.8 | ||

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | 0.78 and 0.73 for the anxiety and depression subscales. | ||

| Job Descriptive Index (JDI) | 0.85 | ||

| Job Stress Survey (JSS) | For the severity and frequency of job pressure, the scores were 0.83 and 0.85, whereas for the severity and frequency of lack of support, the scores were 0.83 and 0.85, respectively. | ||

| Law Enforcement Officer Stress Survey (LEOSS) | 0.87 | 0.67 | |

| Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) | 0.87, 0.73, and 0.80 for the exhaustion, depersonalization, and achievement subscales | ||

| Norwegian Police Stress Survey (NPSS) | For the severity and frequency of serious operational tasks, the scores were 0.82 and 0.83. For the severity and frequency of work injuries, the scores were 0.84 and 0.76, respectively. | ||

| Operational Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ-OP) | 0.94 | 0.7 | |

| Organizational Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ-Org) | 0.94 | 0.72 | |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) | 0.9 | 0.94 | |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | 0.87 | 0.86 | |

| Police mental health ability (PMHA) | 0.863 | 0.73 | |

| Police Role Expectations (PRE) | 0.77 | ||

| Psychological Injury Risk Indicator (PIRI) | 0.83 | 0.64 | |

| Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ20) | 0.84 | ||

| Spanish Burnout Inventory (SBI) | In subscales: work excitement = 0.64; mental exhaustion = 0.85; guilt = 0.79; and indolence = 0.71 | 0.7 | |

| Suicide ideation from Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-II) | 0.85 | ||

| Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) | 0.93 | ||

| The Impact of Event Scale—Revised (TIES-r) | 0.92, 0.83, and 0.85 for the intrusion, avoidance, and hypervigilance subscales | 0.86 | |

| V. Bokyo Burnout Inventory (VBBI) | 0.94 | 0.71 | |

| Work and Well-Being Assessment for Police (WWBAP) | 0.74–0.86 in subscales | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teles, D.O.; Oliveira, R.A.d.; Parnaíba, A.L.d.O.; Rios, M.A.; Machado, M.B.; Aquino, P.d.S.; Menezes, P.R.d.; Ribeiro, S.G.; Soares, P.R.A.L.; Biazus Dalcin, C.; et al. Assessment of the Mental Health of Police Officers: A Systematic Review of Specific Instruments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101300

Teles DO, Oliveira RAd, Parnaíba ALdO, Rios MA, Machado MB, Aquino PdS, Menezes PRd, Ribeiro SG, Soares PRAL, Biazus Dalcin C, et al. Assessment of the Mental Health of Police Officers: A Systematic Review of Specific Instruments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(10):1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101300

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeles, Davi Oliveira, Raquel Alves de Oliveira, Anna Luísa de Oliveira Parnaíba, Mariana Araújo Rios, Melissa Bezerra Machado, Priscila de Souza Aquino, Purdenciana Ribeiro de Menezes, Samila Gomes Ribeiro, Paula Renata Amorim Lessa Soares, Camila Biazus Dalcin, and et al. 2024. "Assessment of the Mental Health of Police Officers: A Systematic Review of Specific Instruments" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 10: 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101300

APA StyleTeles, D. O., Oliveira, R. A. d., Parnaíba, A. L. d. O., Rios, M. A., Machado, M. B., Aquino, P. d. S., Menezes, P. R. d., Ribeiro, S. G., Soares, P. R. A. L., Biazus Dalcin, C., & Pinheiro, A. K. B. (2024). Assessment of the Mental Health of Police Officers: A Systematic Review of Specific Instruments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(10), 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101300