Developing a Public Health Course to Train Undergraduate Student Health Messengers to Address Vaccine Hesitancy in an American Indian Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. DC Online Community Survey Development

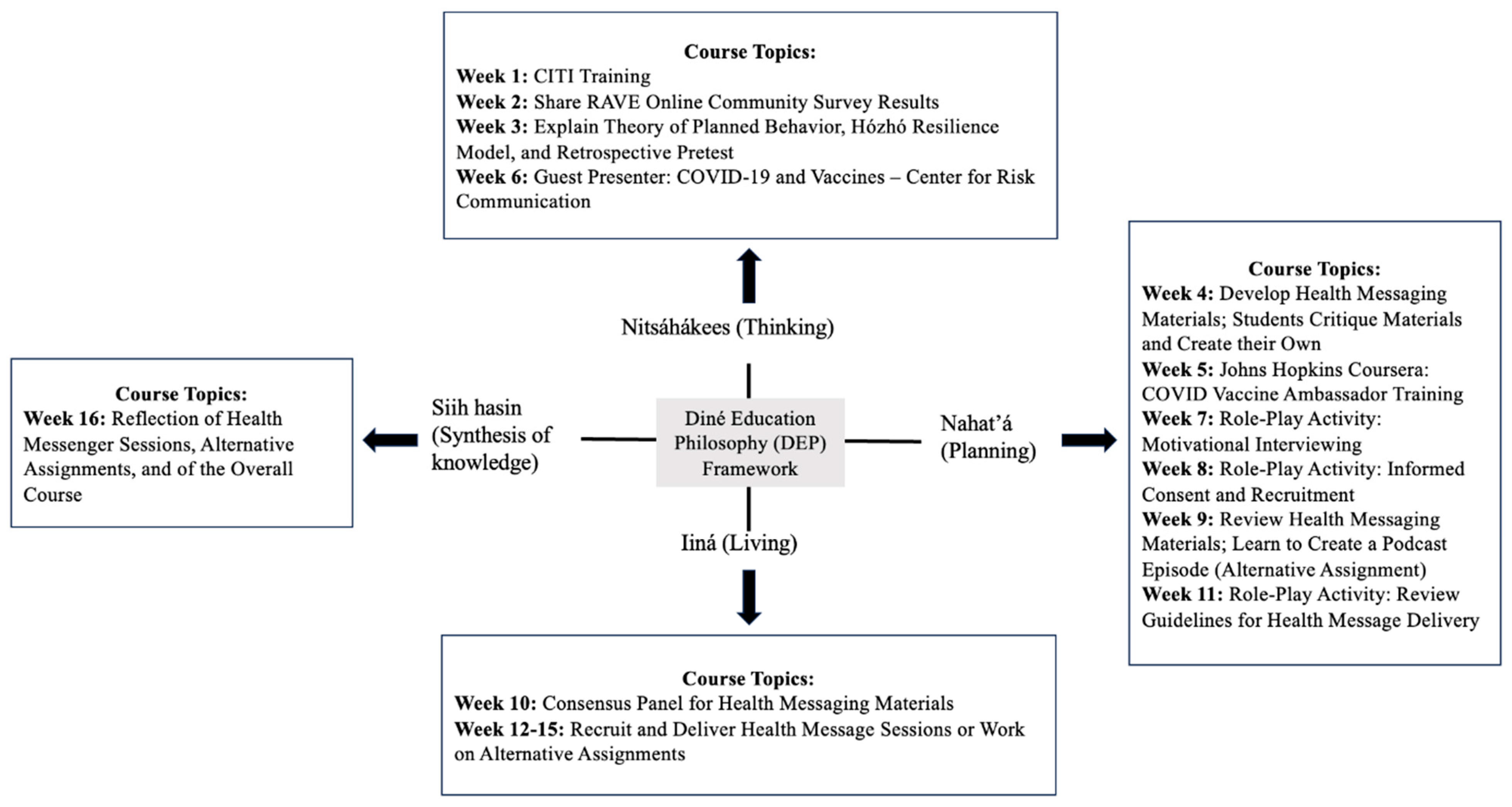

2.2. Diné Educational Philosophy (DEP) Framework

2.3. RAVE Course Development

2.4. RAVE Course

3. Results

3.1. DC Online Community Survey

3.2. Student Health Messaging Education

4. Discussion

4.1. Diné-Centered Pedagogy

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hatcher, S.M.; Agnew-Brune, C.; Anderson, M.; Zambrano, L.D.; Rose, C.E.; Jim, M.A.; Baugher, A.; Liu, G.S.; Patel, S.V.; Evans, M.E.; et al. COVID-19 among American Indian and Alaska Native persons—23 states, January 21—July 3, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, H.; Toropin, K.; Sidner, S.; Perrot, L. Navajo Nation Surpasses New York State for the Highest COVID-19 Infection Rate in the US. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/18/us/navajo-nation-infection-rate-trnd/index.html (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Navajo Nation Department of Information Technology. History. 2022. Available online: https://www.navajo-nsn.gov/History (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Indian Health Service. Navajo Nation. Available online: https://www.ihs.gov/navajo/navajonation/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Calac, A.J.; Bardier, C.; Cai, M.; Mackey, T.K. Examining Facebook community reaction to a COVID-19 vaccine trial on the Navajo Nation. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1428–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data. 2021. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=USA#citation (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Navajo Nation Department of Health. Navajo Nation COVID-19 Dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://ndoh.navajo-nsn.gov/COVID-19/Data (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Willis, D.E.; Andersen, J.A.; Bryant-Moore, K.; Selig, J.P.; Long, C.R.; Felix, H.C.; Curran, G.M.; McElfish, P.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 2200–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locklear, T.; Strickland, P.; Pilkington, W.F.; Hoffler, U.; Billings, V.; Zhang, T.; Brown, L.; Doherty, I.; Shi, X.; Jacobs, M.A.; et al. COVID-19 testing and barriers to vaccine hesitancy in the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. North Carol. Med. J. 2021, 82, 406–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinschmidt, K.M.; Attakai, A.; Kahn, C.B.; Whitewater, S.; Teufel-Shone, N. Shaping a Stories of Resilience model from urban American Indian elders’ narratives of historical trauma and resilience. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Profile: American Indian/Alaska Native. United States Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Minority Health. Available online: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=62#:~:text=Health%%203A%20According%20to%20Census%20Bureau,and%2077.5%20years%20for%%2020men (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- D’Amico, E.J.; Palimaru, A.I.; Dickerson, D.L.; Dong, L.; Brown, R.A.; Johnson, C.L.; Klein, D.J.; Troxel, W.M. Risk and resilience factors in urban American Indian and Alaska youth during the coronavirus pandemic. Am. Indian Cult. Res. J. 2020, 44, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, C.B.; James, D.; George, S.; Johnson, T.; Kahn-John, M.; Teufel-Shone, N.I.; Begay, C.; Tutt, M.; Bauer, M. Diné (Navajo) Traditional Knowledge Holders’ perspective of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 43, 205–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, E.J.; Menking, P.; Begay, M.G. Fighting the COVID-19 merciless monster: Lives on the line-Community Health Representatives’ roles in the pandemic battle on the Navajo Nation. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2020, 44, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.; Park, Y.S.; Israel, T.; Cordero, E.D. Longitudinal evaluation of peer health education on a college campus: Impact on health behaviors. J. Am. Coll. Health 2009, 57, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovi, A.S.; Sheu, H.B. Testing the effectiveness of an SCT-based training program in enhancing health self-efficacy and outcome expectations among college peer educators. J. Couns. Psychol. 2022, 69, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northern Arizona University. Center for Health Equity Research. 2022. Available online: https://nau.edu/cher/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Dreifuss, H.M.; Belin, K.L.; Wilson, J.; George, S.; Waters, A.R.; Kahn, C.B.; Bauer, M.; Teufel-Shone, N.I. Engaging Native American high school students in public health career preparation through the Indigenous Summer Enhancement Program. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 789994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postsecondary National Policy Institute. Native American Students in Higher Education. 2021. Available online: https://pnpi.org/native-american-students/ (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Hanson, M.; College Graduation Statistics. Education Data Initiative. 2022. Available online: https://educationdata.org/number-of-college-graduates (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Diné College. Home. 2022. Available online: https://www.dinecollege.edu/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Werito, V.; Vallejo, P. Conclusion: Toward a Diné-centered pedagogy for transformative educational praxis. In Transforming Diné Education: Innovations in Pedagogy and Practice; Vallejo, P., Werito, W., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2022; pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, M.W.; Nápoles, A.M.; Pérez-Stable, E.J. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 2466–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benally, H. Spiritual Knowledge for a Secular Society: Traditional Navajo Spirituality Offers Lessons for the Nation. Tribal Coll. J. Am. Indian High. Educ. 1992. Available online: https://tribalcollegejournal.org/spiritual-knowledge-secular-society-traditional-navajo-spirituality-offers-lessons-nation/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Kahn-John, M.; Koithan, M. Living in health, harmony, and beauty: The Diné (Navajo) Hózhó wellness philosophy. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2015, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.; Sabo, S.; Chief, C.; Clark, H.; Yazzie, A.; Nahee, J.; Leischow, S.; Henderson, P.N. Diné (Navajo) healer perspectives on commercial tobacco use in ceremonial settings: An oral story project to promote smoke-free life. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. J. 2019, 26, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampa, V.; Smith, C.; Muskett, O.; King, C.; Sehn, H.; Malone, J.; Curley, C.; Brown, C.; Begay, M.; Shin, S.; et al. Cultural elements underlying the community health representative-client relationship on Navajo Nation. BioMed Cent. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutt, M.; Begay, C.; George, S.; Dickerson, C.; Kahn, C.; Bauer, M.; Teufel-Shone, N. Diné teachings and public health students informing peers and relatives about vaccine education: Providing Diné (Navajo)-centered COVID-19 education materials using student health messengers. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1046634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R. What is motivational interviewing? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 1995, 23, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, C.C.; McGuigan, W.M.; Katzev, A.R. Measuring program outcomes: Using retrospective pretest methodology. Am. J. Eval. 2000, 21, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenEpi. Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health. 2013. Available online: https://openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- AuYoung, M.; Espinosa, P.R.; Chen, W.; Juturu, P.; Young, M.D.T.; Casillas, A.; Adkins-Jackson, P.; Hopfer, S.; Kissam, E.; Alo, A.K.; et al. Communications Working Group. Addressing racial/ethnic inequities in vaccine hesitancy and uptake: Lessons learned from the California alliance against COVID-19. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 46, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; Thomson, C.; Sabo, S.; Edleman, A.; Kahn-John, M. Development of an American Indian diabetes education cultural supplement: A qualitative approach. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 790015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumpey, A.J.; Daigle, D.; Nowak, G. Communicating during an Outbreak or Public Health Investigation. The CDC field Epidemiology Manual. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/eis/field-epi-manual/chapters/Communicating-Investigation.html (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Boyd, A.D.; Buchwald, D. Factors that influence risk perceptions and successful COVID-19 vaccination communication campaigns with American Indians. Sci. Commun. 2022, 1, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Demographics (N = 50) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24: 9 | 25–44: 27 | 45–54: 8 | 55+: 5 |

| Gender | Female: 42 Male: 7 Other: 1 | |||

| A DC student | Yes: 31 | No: 19 | ||

| Employed at DC | Yes: 19 | No: 30 | ||

| Highest level of education | HS: 3 Some College: 14 AA/AS: 16 BA/BS: 12 Grad Sch: 5 | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | Yes: 3 | No: 47 | ||

| Racial Category | Native American: 50 | White/Caucasian: 2 | ||

| Live with individuals over 60 * | Yes: 13 | No: 37 | ||

| Live with children under 18 * | Yes: 30 | No: 20 | ||

| * Three participants lived both with individuals over 60 and children under 18 | ||||

| Count of Question Responses | ||||

| Occupation | 50 | |||

| Employment status (check all that apply) | 59 | |||

| Tribal affiliation | 47 | |||

| City and state of residence | 48 | |||

| Received one shot of a COVID-19 vaccine | 50 | |||

| Fully vaccinated | 49 | |||

| Reason for vaccination (check all that apply) | 167 | |||

| Concerned about Covid-19 vaccine safety | 50 | |||

| Hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine | 49 | |||

| Respondent had COVID-19 | 50 | |||

| (None, few, some, many) relatives seem COVID-19 vaccine hesitant | 50 | |||

| Reasons relatives expressed for COVID-19 vaccine hesitance (check all that apply) | 137 | |||

| (None, few, some, many) peers seem COVID-19 vaccine hesitant | 49 | |||

| Reasons peers expressed COVID-19 vaccine hesitance (check all that apply) | 128 | |||

| Number of close relatives who had COVID-19 | 50 | |||

| Number of peers who had COVID-20 | 50 | |||

| Number of close relatives who died from COVID-19 | 50 | |||

| Number of peers who died from COVID-20 | 50 | |||

| News engagement of vaccine-hesitant peers and relatives | 49 | |||

| News sources of vaccine-hesitant peers and relatives (check all that apply) | 123 | |||

| Political engagement of vaccine-hesitant peers and relatives | 49 | |||

| Follow the News Closely | News Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Agreed | 56% (28) | 60% (30) | |

| Disagreed | 42% (21) | Local Television | 54% (27) |

| Follow Politics Closely | Radio | 32% (16) | |

| Agreed | 44% (22) | Local Newspapers | 24% (12) |

| Disagreed | 16% (8) | Unsure | 24% (12) |

| Neutral | 38% (19) | National Sources | <20% (<10) |

| Question | Pretest | Post | Change | p-Value | Pretest | Retro-Spective Pretest | Change | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I understand the background of COVID-19 well enough to explain it to my family members and friends. | 61.54% | 92.31% | 50.00% | 0.080 | 61.54% | 53.85% | −12.50% | 0.50 |

| I understand at least one COVID-19 vaccine well enough to explain how it works to my family members and friends. | 46.15% | 92.37% | 100.00% | 0.015 | 46.15% | 61.54% | 33.33% | 0.348 |

| I feel confident to share health messages about COVID-19 and vaccines with my family members and friends. | 76.92% | 92.31% | 20.00% | 0.297 | 76.92% | 53.85% | −30.00% | 0.206 |

| I feel I could make a difference in the health of my family members and friends by sharing the knowledge I currently have about COVID-19 and vaccines. | 84.62% | 92.31% | 9.10% | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Begay, C.; Kahn, C.B.; Johnson, T.; Dickerson, C.J.; Tutt, M.; Begay, A.-R.; Bauer, M.; Teufel-Shone, N.I. Developing a Public Health Course to Train Undergraduate Student Health Messengers to Address Vaccine Hesitancy in an American Indian Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101320

Begay C, Kahn CB, Johnson T, Dickerson CJ, Tutt M, Begay A-R, Bauer M, Teufel-Shone NI. Developing a Public Health Course to Train Undergraduate Student Health Messengers to Address Vaccine Hesitancy in an American Indian Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(10):1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101320

Chicago/Turabian StyleBegay, Chassity, Carmella B. Kahn, Tressica Johnson, Christopher J. Dickerson, Marissa Tutt, Amber-Rose Begay, Mark Bauer, and Nicolette I. Teufel-Shone. 2024. "Developing a Public Health Course to Train Undergraduate Student Health Messengers to Address Vaccine Hesitancy in an American Indian Community" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 10: 1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101320