Charting the Characteristics of Public Health Approaches to Preventing Violence in Local Communities: A Scoping Review of Operationalised Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

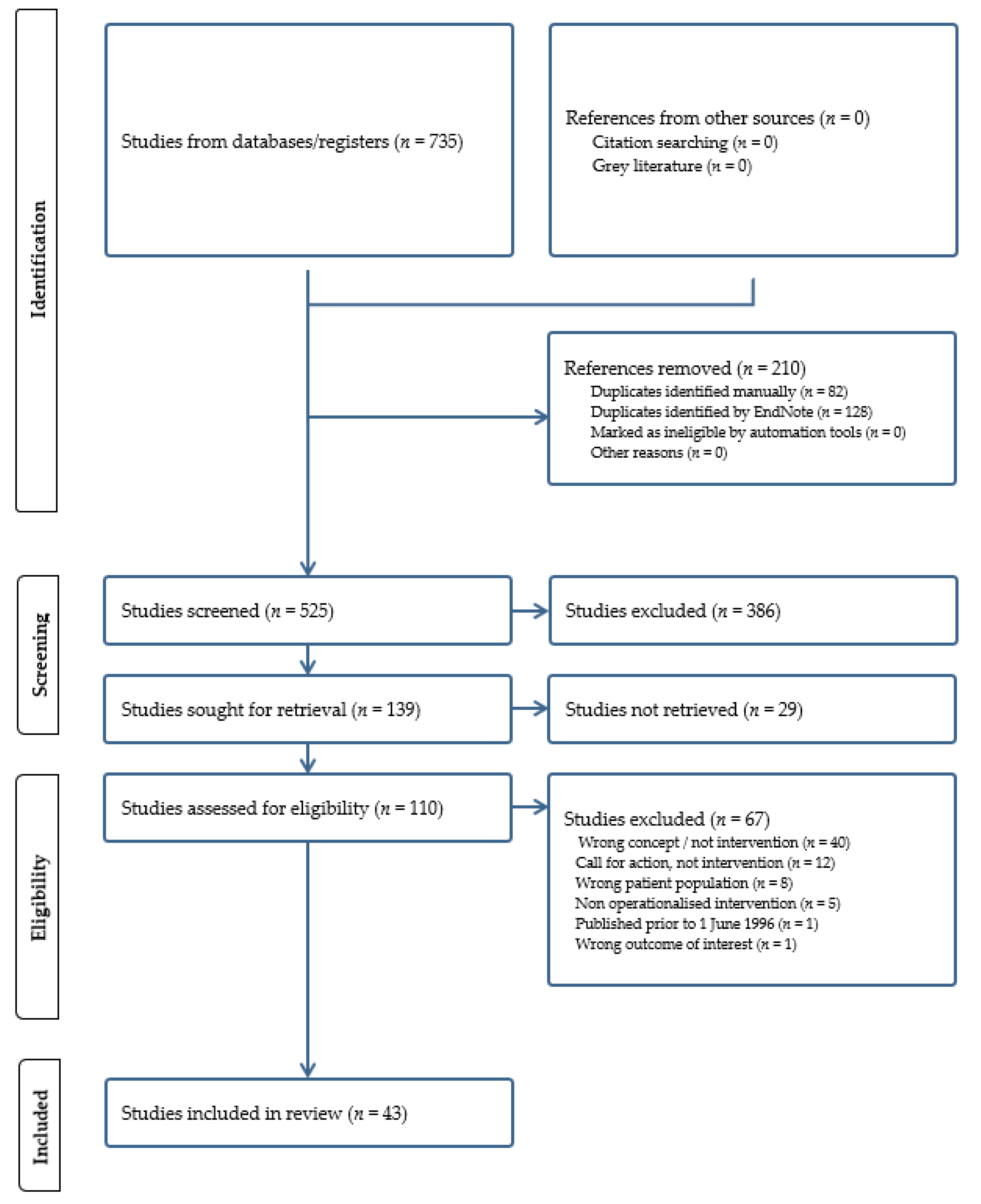

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Participants—Public health and partner agencies operating at the sub-national level, and populations identified at risk of interpersonal violence.

- Concept—The characteristics of multi-agency, operationalised interventions described as following a public health approach to prevent/address/control such violence (what values and principles drive these and what their components are).

- Context—Included interventions were operationalised in sub-national geographies/areas; are not limited to a specific region of the world; and address interpersonal types of violence including physical, sexual, psychological, and neglect, where these were included in a self-described public health approach to violence.

2.3. Databases and Searches

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

3.2. Identified Characteristics

3.3. Major Influences of Interventions

| Major Influences Driving Interventions |

|---|

| Concern at the scale and impact of violence: - High rates of gun/weapon violence [2,16,17,18,20,21,22,24,25,27,28,29,32,35], youth violence [19,23,26], intimate partner violence (IPV) [30,33], child sexual exploitation (CSE) [7], alcohol [34], fixated threats [31] - Concern over homicide as key driver [17,23,29,36,37], particularly within Black/minority groups [26] - Community and social costs [30,34], economic costs [21,34,37] - Outcomes on victims of IPV [30] - Prevalent community norms including acceptability of IPV [30], violence/weapon carrying [20,22,36] - Future impact of exposure [26] - Gang-related retaliations [49] and territoriality [22] - School shootings in the United States of America (USA) [50] - Disparities in impact—ethnicity and gender and disadvantage communities [2,28,35,37] Growing understanding of varying/complex influences on violent behaviours: - Structural/internalised racism [28] - Recognition of complex root causes [2,18,21,22,25] and factors operating across the socioecological model (SEM) [23,43,49,51] - IPV closely linked to male dominance in society and reflective of inequalities [30,40] Increased adoption of public health approach/theory: - Influence of public health approaches including World Health Organisation (WHO) calls for action [9,21,28,29,38,39] - Primary prevention as best evidenced (e.g., parental programmes), but action throughout life course and levels recognised to be necessary [49,51], evidence highlighting the potential to break cycles of violence [26] - Examining targeted and universal applications of empirically supported violence prevention in school teaching [46] - Increasing interest in trauma informed approaches including the impact of exposure to violence and future victimisation and perpetration [21,28] - Influence of USA community initiative models but tailored to local area [18,22] - Importance of addressing gaps in evidence base [29,30,45,46] Advocacy by community: - Community-led commission/advocacy [2,35] Advocacy of service providers/improvements to healthcare: - Healthcare provider-led advocacy and recognition of role in anti-violence [21,26,32,42,44] - Desire to improve post-event follow up and treat non-physical injuries [26,28,42] - Recognition law enforcement data is incomplete versus Emergency Department (ED) health records on violence attendances [34,52] - Systematic barriers to safety, permanent sense of acute crisis, lack of trust and safety for both staff and patients in healthcare, defensiveness [28] - Development of integrated hospital-based intervention approach after separate sexual and domestic violence teams [27] Desire for improved use of resources and partnerships: - Leading consumer of healthcare resources (compared to other issues) [32] - Desire for strategic collaboration and response [25] - Desire to bring together existing programmes [29] - Refinement/development of programmes already in existence [33,43] Limited or negative impacts of criminal justice approaches: - Law enforcement limited long term impact alone and not sustainable [17,18,36,39], a reactive law enforcement approach to IPV [9,40,41] - Iatrogenic effects of incarceration [39] Policy direction and/or funding: - Availability of funding [21,27,33,36,44,45,46] - National guidance and policy/call for action [23,34,43] - Legal obligations introduced at USA state level [40] - National development of research and potential of preventive interventions [7,45] Context specific drivers/delivery mechanisms: - Response to pressure on civil society following apartheid [29] - Response to specific events, e.g., community/police tensions [21] - Use of community health workers as one of limited options in lower middle-income countries (LMICs)—resources intensive models not transferable [47] Examples for specific types of violence—violence against sex workers: Influence of rights-based approaches: - Human rights and violence prevention intervention to focus on violence prevention, response, and/or police treatment of sex workers [48] |

3.4. Values and Principles

| Values/Principles Informing Interventions |

|---|

| Violence as a communicable disease (CD): - Controlling exposure and transmission through CD methods (at the individual level) [17,18,20,21,24,38,49,53] Prevention at the core (inc. targeted/multi-levelled approaches): - Prevention and improving health and safety at a population level [18,25,29,36] - Primary preventative approach for at-risk families/children/adolescents [7,9,33,41,43,45,46,53,54] - Promotion of positive parenting strategies/reduce negative or coercive strategies [45,46,47], and a focus on maternal mental health [47] - Adoption of secondary and tertiary prevention principles [26,51] and harm reduction approaches [31] - Influence of universal and targeted approaches [46,51] - Primary prevention of CSE—focus on adults and involvement of adults whether or not perpetrators (rather than waiting for children to disclose). Belief that abusers can stop and should be offered support, whilst being held accountable [54] Focus on complex causes including social determinants of health: - Address constellation of risk factors—recognise fundamental problems with relationships with other, e.g., family [30,41,43] - Informed by science, common causal factors, and early intervention [46] - Recognising complex health inequalities require integrated multi-level approach required (e.g., complex risk factors including stigma, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unintended pregnancies, exposure to violence, human rights violations) [48] - Addressing structural and social determinants of health (including post-event) [16,21,22,23,24,29,42] Optimising opportunities to shift norms and attitudes: - Opportunities from focusing on post-event ‘teachable moments’ [24,26,27,42] - Prevention of re-victimisation/cycle of violence [27], promotion of alternative norms and less harmful resolutions [17,36,51], addressing the complex nature of gang memberships [49] - Address community acceptability of violence/social justice approach [19] - Addressing power dynamics and negative dominant narratives about young people [23], primary and secondary activity to address norms and stereotyping—combination of individual and community/societal levels [30,54] - Combining identification of high-risk and broader education for wider community [17] - Attempt to sensitise authorities to scale of issue [32], including IPV [9,30] - Promotion of healthy relationships [43] - Engagement of parents and educators as strong influences at age 11–14 [43] - Tackling perceptions that violence is not preventable (relating to child maltreatment) [46,53] Role of partnership and stakeholder in the development and sustainment of interventions: - Partnership approach (including long term approach) [2,18,20,22,25,44,53] - Benefit of bringing together multiple organisations/perspectives to identify complex causes and consequences [18,27,35,37,44] Use of data and intelligence to target use of limited resources/innovate interventions: - Focusing of limited enforcement and intervention activities through analysis and innovative response [2,25,37,44] - Benefit of collaboration including use of data [34] - Contextual social analysis to complement technical knowledge [29] Incorporation of enforcement and health-focused approaches: - Balance of enforcement and rehabilitation and support [18,22,39] - Enhancing student safety through environmental school route safety improvement/and active travel [50] - Mandatory training as an atypical use of legal framework within public health approach on IPV [40] - Reduce formal approach and limit police involvement at early stages of response [40], diversion from criminal justice approaches [31] - Complementary to law enforcement [41] Trauma-informed approaches: - Trauma-informed approach to address mental health consequences of violent injury, prevent re-injury, and improve life course trajectories of injured youth [28] - Addressing the cycle of violence—‘hurt people hurt people’—informed by the psychological, biological, and behavioural risk factors that derive from violence and adversity (including in childhood) [26] Community and practitioner involvement and advocacy: - The unique role of practitioners to witness and influence [27,29,32] - Recognition of potential role of nurses/health staff [34,52], education and support for staff [28] - Encouraging community responsibility [54] - Grounded in experiences of and advocacy by sex workers, to address legal and structural barriers [48] - Utilisation of specific contexts, e.g., a unique social context and trusted relationships (to receive sensitive information/deliver help) [40] - Combining public health (quantitative/population level) and community development approaches (organic/bottom up) [29] Human rights based approach: - Raising awareness of women’s human rights [30,48] Examples for specific types of violence—intimate partner violence: Cognisance of age-appropriate interventions: - Address transient relationships at this age [43] - Focus on foundational stages of development [43], acknowledge differences to other youth violence [43] Capacity building: - Hypothesised to lead to prevention activities (initiating or expanding prevention activities) [33] Informed by behavioural change theory: - Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of behaviour informed design [30] Development of approach in low-income environment (recognising most developed in high-income) [29] |

3.5. Key Components of Interventions

| Key Components of Interventions |

|---|

| Violence interruption to prevent individual/group conflicts (at the individual level): - Using violence interrupters to detect and interrupt conflicts, identifying and treating highest-risk people [16,17,18,19,20,21,36,38,51] Case management and support at the individual level: - Outreach workers—connect, challenge thinking, engage, and link high risk with positive alternative opportunities (or similar) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,36,38,49] - Case workers: embedded within/link with EDs to engage with victims—intensive case management and wrap-around including referrals to community resources and peer support—may include home visit and follow-up [2,24,26,27,28,29,42,51], support for adolescents in abusive relationships [29,30] - Tiered approach to prevent child maltreatment from brief consultations to longer term depending on risk [45], multi-level parenting programmes [46], including intensive home visiting [47] and home safety and child health training [45], and support during pregnancy [53] - Development and offer of treatment to possible child sex offenders [7] - 24 hr crisis management to address violence and advocates during wrongful arrest of sex workers [48] - Maintenance of specialist case management system for fixated threats. Cases assessed and joint police/mental health assessment of appropriate health or police action [31] Addressing individual trauma and past experiences of contact with service providers: - Culturally competence leads to address previous negative experiences of healthcare [28] - Seek to understand issues, communication, and trauma, and address anger [27,28,42], educating staff on effects of trauma and stress, mindsets of clients, and tools to change individual and group behaviours - using SELF concepts ie. Safety, Emotions, Loss, Future [26,28,29] Development of alternative activities and community assets: - Creation of alternatives for communities and upstream universal approaches, responding to local risk and protective factors, use of community assets [18] - Mandatory recognition and signposting training for salon workers (not mandatory reporting) [40] Social marketing approaches and shifting norms at community level: - Changing behavioural and social norms through community programmes and events [17,18,20,36,38,46] - Social marketing anti-violence campaign [24,32], specific attempts to reframe IPV using media and outreach [30,33] - Promotion of ‘guiding responsibilities and expectations in adolescents’ and positive racial identities [19,23,49,51] - Media and community campaigns to raise awareness of child sexual abuse (CSE) warning signs [54], advertising of treatment for potential offenders [7], helpline for potential CSE abusers, friends and family of suspected abusers, and concerned community members [54] Advocating for change with policy makers: - Explicit aim to influence local and national policy makers (bottom up), including legislators [29,30,32,33] Improved use of data and intelligence: - Use of data to inform approach on specific conflicts and identify highest risk [2,17,18,19,21,22,25,36,39], including IPV [46], and ED statistics [34,52] - Data sharing within partnerships to inform prevention strategies [34,52] - Post-event review of homicides to inform future prevention activity [37] - Systematic data collection to inform design [30] and understand attitudes to physical abuse of children [53] Key role for ‘partnerships’: - Use or creation of formal/multi-agency partnerships [2,9,17,18,21,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,33,34,35,36,37,39,42,52] - Co-production within partnerships [18] Criminal justice included in the approach: - Potential enforcement as integral part of approach [18,22,37,39,49]/targeting of hot-spots [18] - Emphasis on voluntary participation and collective gang responsibility—self-referral and behaviour contracts (with no incentive aside from offer of support) [18,22] - Reducing school based arrests and diversion from criminal justice [35], incorporation of restorative justice [23] - Skill-building and legal empowerment for sex workers [48] Wider determinants component: - Environmental improvements, e.g., improved physical conditions on school routes, safer pathway, police presence on travel routes [18,35,50], and clean and green initiatives [23] - Economic and social development—community and small business partnerships seen as primary prevention [29], job creation and skills [35,53], parental support, health and wellness, behavioural/mental health, basic needs, and food insecurity [35] Primary prevention early in life course: - Primary prevention activities within antenatal/childhood/families (e.g., enhanced home visiting) [18,39] - School referrals for disruptive pupils at early elementary school—parental training (positive reinforcement, effective punishments, and monitoring) and pro-social skills for children [51] Educational setting as a hub for interventions: - Universal school-based programmes focusing on social and emotional development [18,29] and targeted interventions for high-risk youth in school curricula. Universal interventions for all students at grade level/risk screening in school health centres [23,46] - Continuum of support for children, young people, and families: after/summer school activities, school enrichment [35,53] - After school projects and alternative suspension programmes and academic support/counselling for suspended pupils [35] - School-based programmes for IPV for 13–15-year-olds—changing norms regarding dating/gender stereotyping/conflict management/bystander strategies [30,33,41,43,54]; training for parents and teachers [43] - Education and training for university students about risk factors for sexual abuse, empowering peer interventions, and encouraging reporting. Aimed at reducing victimisation, as well as how to talk to someone who may be at risk of harming someone or being harmed [7] Development and evaluation of interventions: - Pre-intervention—significant investment in engagement with internal and partner support and buy in, and community resource network [27,29] - Ongoing development of interventions [18,25] staged approach to develop, build networks, consolidate over time [30] Community mobilisation: - Significant community engagement in planning of intervention [29] - Community mobilisation/dialogue [23,30,49] - Faith-based leader involvement [49] Capacity building: - Creation of formal offices focusing on violence prevention [2,44] - Building capacity of local health departments, e.g., boost surveillance by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) work with communities to identify indicators for teen dating IPV [9,30,33,43] - Health/cross-sector provider training [30,32,33,45,46], including for child abuse [47], violence against sex workers, and police training on sex work/STIs and legal position [48] |

3.6. Role of Community Engagement and Involvement

| Presence/Method of Community Engagement |

|---|

| Community members integral to delivery: - Community members run interventions and/or train health workers on violence reduction [20,21,29,38] - Violence Interrupters/Outreach workers live in the same communities (may have violent histories/prison experience). Used due to having the ‘street knowledge’ that ‘cannot be taught’. Credible messengers and un-judgemental [17,20,21,24,36,38], youth [23,51] - Influential older youth to act as ‘brand ambassadors’/use of recognised older authority figures in communities [30,43] - Blue Ribbon Commission leading intervention as a grassroots organisation [35] - Community consultation to listen and review and recommend on actions to prevent homicides [37] - Community resilience teams formed by neighbourhoods to increase engagement, cohesion, and resilience in response to chronic violence [16] Community mobilisation an integral part of intervention: - Community mobilisation and events including rallies, marches, and barbecues to propagate anti-violence messages and positive relationships with police and politicians [17,18,21,29,38]; training and social marketing within IPV responses [30,33]; community coalition building—building of unified no violence messaging and immediate response when violence occurs [17,18] and in response to youth violence [23,49] - Empowerment through community advocacy groups [48] Community assets as a source of referral and support: - Community agencies and resources as a source of referral/support/assets [18,21,22,27,29,42], including IPV [30,40] and violence against sex workers [48] - Use of culturally diverse locations to deliver IPV intervention [40] Insight an explicit part of intervention development: - Community (individuals/groups) as a source of understanding and context building in development of intervention [18,27,29] including IPV response [9,30], developing collaborations to ensure cultural and context of youth violence response is appropriate [19,23,26]; ensure IPV response socio-culturally relevant to ensure communities can make surface adaptations (without impacting on effectiveness) [43] - Focus on ethical protections for use of data (given minority communities’ experience of structural racism in this arena) [2] - Importance of continuous negotiations between formal and organic indigenous knowledges; managing leadership tensions and vested interests in changing communities; nurturing of partnerships [29] |

3.7. Intervention Outcomes

3.8. Variety of Public Health Approaches to Addressing and Preventing Violence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategies

| Date of Search | Database | Platform | Terms | Filters | Results |

| 10 May 2023 | Cochrane Library | https://www.cochranelibrary.com/?contentLanguage=eng | “public health approach*”:ti,ab AND violen*:ti,ab | June 1996–April 2023 | 4 |

| 10 May 2023 | APA PsychoInfo | https://ovidsp.dc1.ovid.com/ovid-a/ovidweb.cgi | Public health approach*.ti,ab AND Violen*.ti,ab | 1996–2023 English Not related terms | 157 |

| 10 May 2023 | Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts | ProQuest.com | (ab(“public health approach??”) OR ti(“public health approach??”)) AND (ab(violen??) OR ti(violen??)) | English June 1996–April 2023 | 58 |

| 10 May 2023 | Public Health Database | Proquest.com | (ab(“public health approach??”) OR ti(“public health approach??”)) AND (ab(violen??) OR ti(violen??)) | English June 1996–April 2023 | 103 |

| 10 May 2023 | Medline | Ovid Medline | Public health approach*.ti,ab AND Violen*.ti,ab | 1996–2023 English Not related terms | 172 |

| 12 May 2023 | TRIP Pro | https://www-tripdatabase-com.uoelibrary.idm.oclc.org/ | (“public health approach” OR “public health approaches”) AND (violence OR violent) | (No date filter but earliest study was 2000) | 241 |

References

- World Health Organisation. Violence Info. Available online: https://apps.who.int/violence-info/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Mayfield, C.A.; Siegal, R.; Herring, M.; Campbell, T.; Clark, C.L.; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. A Replicable, Solution-Focused Approach to Cross-Sector Data Sharing for Evaluation of Community Violence Prevention Programming. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, S43–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Assembly. Forty-Ninth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 20–25 May 1996: Resolutions and Decisions, Annexes. 1996. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/178941 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. 2022. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- World Health Organisation. Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Krug, E.G.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Mercy, J.A.; Zwi, A.B.; Lozano, R.; World Health Organisation. World Report on Violence and Health. 2002. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42495 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Tabachnick, J. Why prevention? Why now? Int. J. Behav. Consult. Ther. 2013, 8, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hurst, A.; Shaw, N.; Carrieri, D.; Stein, K.; Wyatt, K. Exploring the rise and diversity of health and societal issues that use a public health approach: A scoping review and narrative synthesis. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graffunder, C.M.; Noonan, R.K.; Cox, P.; Wheaton, J. Through a Public Health Lens. Preventing Violence against Women: An Update from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J. Women’s Health 2004, 13, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Violence Reduction Unit. Available online: http://www.svru.co.uk/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Home Office. Serious Violence Duty; Preventing and Reducing Serious Violence: Statutory Guidance for Responsible Authorities December. 2022. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/639b2ec3e90e072186e1803c/Final_Serious_Violence_Duty_Statutory_Guidance_-_December_2022.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Jagosh, J. Realist Synthesis for Public Health: Building an Ontologically Deep Understanding of How Programs Work, for Whom, and in Which Contexts. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294736492_Methodology_for_JBI_Scoping_Reviews (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidogun, T.M.; Alyssa Ramnarine, L.; Fouladi, N.; Owens, J.; Abusalih, H.H.; Bernstein, J.; Aboul-Enein, B.H. Female genital mutilation and cutting in the Arab League and diaspora: A systematic review of preventive interventions. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2022, 27, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, A.; Duffany, K.O.C.; Carroll-Scott, A.; Thomas, J.; Greene, A.; Arora, A.; Agnoli, A.; Gan, G.; Ickovics, J. Bridging the response to mass shootings and urban violence: Exposure to violence in New Haven, Connecticut. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butts, J.A.; Roman, C.G.; Bostwick, L.; Porter, J.R. Cure violence: A public health model to reduce gun violence. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Preventing Serious Violence: A Multi-Agency Approach. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/preventing-serious-violence-a-multi-agency-approach (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Cerda, M.; Tracy, M.; Keyes, K.M. Reducing Urban Violence: A Contrast of Public Health and Criminal Justice Approaches. Epidemiology 2018, 29, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barna, M. Violence interrupters using tested methods to save lives. Nation’s Health 2021, 50, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Tibbs, C.D.; Layne, D.; Bryant, B.; Carr, M.; Ruhe, M.; Keitt, S.; Gross, J. Youth Violence Prevention: Local Public Health Approach. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2017, 23, 641–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.; Currie, D.; Linden, W.; Donnelly, P. Addressing gang-related violence in Glasgow: A preliminary pragmatic quasi-experimental evaluation of the Community Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV). Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Inverno, A.S.P.; Bartholow, B.N.P. Engaging Communities in Youth Violence Prevention: Introduction and Contents. Am. J. Public Health. 2021, 111, S10–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrup, J. Knife Crime: Where’s The Public Health Approach? The Journal of The Health Visitors’ Association. Community Pract. 2022, 92, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, S.; Weegenaar, C.; Avery, P.; Snell, T.; Lockey, D. Use of a national trauma registry to target violence reduction initiatives. Injury 2022, 53, 3227–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, T.J.; Rich, J.A.; Bloom, S.L.; Delgado, D.; Rich, L.J.; Wilson, A.S. Developing a trauma-informed, emergency department-based intervention for victims of urban violence. J. Trauma Dissociation 2011, 12, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Shah, A.K.; Strange, C.; Stillman, K. Hospital-based violence intervention: Strategies for cultivating internal support, community partnerships, and strengthening practitioner engagement. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2022, 14, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, J.; Harris, E.J.; Bloom, S.; Ra, L.; Rich, L.; Corbin, T. Intervening in the community to treat trauma in young men of color. In APA Handbook of Psychology and Juvenile Justice; Heilbrun, K., DeMatteo, D., Goldstein, N.E.S., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.; Seedat, M.; Swart, T.M.; van der Walt, C. Promoting Methodological Pluralism, Theoretical Diversity and Interdisciplinarity Through a Multi-Leveled Violence Prevention Initiative in South Africa. J. Prev. Interv. Commun. 2003, 25, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagman, J.A.; Namatovu, F.; Nalugoda, F.; Kiwanuka, D.; Nakigozi, G.; Gray, R.; Wawer, M.J.; Serwadda, D. A public health approach to intimate partner violence prevention in Uganda: The SHARE Project. Violence Against Women 2012, 18, 1390–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmow, C.; Gill, P.; Corner, E.; Farnham, F.; Taylor, R.; Wilson, S.; Taylor, A.; James, D. A data-driven classification of outcome behaviors in those who cause concern to British public figures. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2021, 27, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, M.; Ormhaug, C.M.; Mtonga, R.E.; Loretz, J. Armed Violence: A Health Problem, a Public Health Approach. J. Public Health Policy 2023, 28, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, K.E.; Zakocs, R.; Le, B.; Hill, J.A.; Brown, P.; Wheaton, J. Evaluation of DELTA PREP: A Project Aimed at Integrating Primary Prevention of Intimate Partner Violence Within State Domestic Violence Coalitions. Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 42, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J. Preventing alcohol-related violence: A public health approach. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2016, 17, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, K.W.; Maume, M.O.; Jones Halls, J.; Smith, S.D. Multisectoral approaches to addressing youth violence. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2017, 27, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.W.; Whitehill, J.M.; Vernick, J.S.; Curriero, F.C. Effects of Baltimore’s Safe Streets Program on gun violence: A replication of Chicago’s CeaseFire Program. J. Urban Health 2013, 90, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Woods, L.; Cisler, R.A. The Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission: An interagency collaborative process to reduce homicide. WMJ 2007, 106, 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Riemann, M. Problematizing the medicalization of violence: A critical discourse analysis of the ‘Cure Violence’ initiative. Crit. Public Health 2019, 29, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, B.C. Public health and the prevention of juvenile criminal violence. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2005, 3, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, J. Hairdos and Help-seeking: Mandatory Domestic Violence Training for Salon Workers. Am. J. Law Med. 2022, 48, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, P.M. The public health approach to the prevention of sexual violence. Sex. Abus. J. Res. Treat. 2000, 12, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.K. Gun violence as public health. Mod. Healthc. 2022, 51, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Tharp, A.T. Dating mattersTM: The next generation of teen dating violence prevention. Prev. Sci. 2012, 13, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidenbach, K.N. Determinants of Implementation Effectiveness of State-based Injury and Violence Prevention Programs in Resource-Constrained Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, May 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, D.J.; Lutzker, J.R.; Shelley, G.A. Child Maltreatment Prevention Priorities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child Maltreat. 2005, 10, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, W.; Whitaker, D.J.; Lutzker, J.R.; Mercy, J.; Chin, P.M. Setting a violence prevention agenda at the centers for disease control and prevention. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2006, 11, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeen, S.; Tomlinson, M. A public health approach to preventing child abuse in low- and middle-income countries: A call for action. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.; Viswasam, N.; Abdalla, P. Integrated Interventions to Address Sex Workers’ Needs and Realities: Academic and Community Insights on Incorporating Structural, Behavioural, and Biomedical Approaches. In Sex Work, Health, and Human Rights: Global Inequities, Challenges, and Opportunities for Action; Goldenberg, S.M., Morgan Thomas, R., Forbes, A., Baral, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Chapter 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, F.G.; Goodall, C.A.; Gavine, A.J.; Williams, D.J.; Donnelly, P.D. Public health, youth violence, and perpetrator well-being. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2015, 21, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, G. A Secondary Spatial Analysis of Gun Violence near Boston Schools: A Public Health Approach. J. Urban Health 2018, 95, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, D.D.; Logan, J.E.; Schneiderman, J.U. Supporting Gang Violence Prevention Efforts: A Public Health Approach for Nurses. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2014, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, T.R.; Hurvitz, K. Healthy People 2020 Objectives for Violence Prevention and the Role of Nursing. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2014, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B. Latin America looks to violence prevention for answers. Lancet 2012, 380, 1297–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, K.C. Implications of public health for policy on sexual violence. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2003, 989, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Systems, H.L. Human Learning Systems. Available online: https://www.humanlearning.systems/ (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Brogan, A.; Eichsteller, G.; Hawkins, M.; Hesselgreaves, H.; Jennions, B.N.; Lowe, T.; Plimmer, D.; Terry, V.; Williams, G. Human Learning Systems: Public Service for the Real World; Centre for Public Impact: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.centreforpublicimpact.org/assets/documents/hls-real-world.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on Preventing Violence against Children 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/violence-prevention/global-status-report-on-violence-against-children-2020 (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Mikton, C.R.; Tanaka, M.; Tomlinson, M.; Streiner, D.L.; Tonmyr, L.; Lee, B.X.; Fisher, J.; Hegadoren, K.; Pim, J.E.; Wang, S.-J.S.; et al. Global research priorities for interpersonal violence prevention: A modified Delphi study. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crerar, P. Untreated Mental Health Issues Too Often Leading to Violent Crimes, Says Khan. The Guardian. 1 May 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2024/may/01/mental-health-services-key-to-preventing-violent-crimes-says-khan (accessed on 15 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mennear, P.J.; Hurst, A.; Wyatt, K.M. Charting the Characteristics of Public Health Approaches to Preventing Violence in Local Communities: A Scoping Review of Operationalised Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101321

Mennear PJ, Hurst A, Wyatt KM. Charting the Characteristics of Public Health Approaches to Preventing Violence in Local Communities: A Scoping Review of Operationalised Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(10):1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101321

Chicago/Turabian StyleMennear, Peter John, Alison Hurst, and Katrina Mary Wyatt. 2024. "Charting the Characteristics of Public Health Approaches to Preventing Violence in Local Communities: A Scoping Review of Operationalised Interventions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 10: 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101321

APA StyleMennear, P. J., Hurst, A., & Wyatt, K. M. (2024). Charting the Characteristics of Public Health Approaches to Preventing Violence in Local Communities: A Scoping Review of Operationalised Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(10), 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21101321