Abstract

Despite the health benefits of physical activity (PA), many individuals do not meet PA recommendations. Family-centered PA approaches, particularly active engagement by Mexican-heritage fathers, may support family PA. This study reports PA outcomes of a culturally tailored, father-focused, and family-centered, program for Mexican-heritage families. Promotora researchers recruited participating families (n = 59, n = 42 complete cases), consisting of children (mean age: 10.1 [SD = 0.9]), fathers, and mothers from five randomly selected geographic clusters in low-resourced colonias in south Texas, in a stepped-wedge randomized design. PA was measured using wrist-worn ActiGraph GT9X accelerometers. Statistical analyses for moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA), light PA (LPA), and sedentary time for the child, father, and mother were conducted using linear mixed models. The findings were as follows: children had no significant changes in MVPA (p = 0.18), LPA (p = 0.52), or sedentary behavior (p = 0.74); fathers had no significant changes in MVPA (p = 0.94), LPA (p = 0.17), or sedentary behavior (p = 0.15); and mothers had a significant decrease in LPA (p < 0.01), and no significant changes in MVPA (p = 0.66) or sedentary behavior (p = 0.77). Despite null results, this study provides an example of a culturally tailored, family-focused program implemented among Mexican-heritage families with limited PA resources and opportunities. Future PA interventions may require higher PA-focused doses over longer time periods to produce a significant change in LPA, MVPA, or sedentary time.

1. Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is consistently supported as a preventative strategy to decrease the risk of chronic diseases and promote healthy physical and mental functioning [1]. PA is associated with improved quality of life, mental health, and cognition [2]. While there are benefits to PA across the lifespan, only 26.1% of children [3] and 23% of adults in the United States (U.S.) [4,5] meet PA guidelines. PA guidelines suggest that children participate in at least 60 min of daily PA, including bone and muscle-strengthening activities [6,7]. Adults are recommended to attain 150–300 min of moderate intensity or 75–150 min of vigorous intensity PA (or a combination of the two), and to engage in muscle-strengthening PA weekly [6,7]. Guidelines also suggest that adults and children reduce time spent doing sedentary behaviors [6,7]. Public health interventions to increase adherence to PA guidelines are increasingly prioritizing populations and communities with limited access to health-promoting resources to offer more PA opportunities [8,9,10].

A subpopulation of individuals who face substantial barriers to PA participation and chronic disease prevention are Mexican-heritage families who reside in colonias in the Lower Rio Grande Valley on the U.S.–Mexico border. Colonias along the Texas border are systematically underserved due to their lack of access to basic infrastructure (i.e., drinking water, sewage treatment, paved roads), their isolated geographic locations, high poverty rates, lack of access to quality health care and health promotion initiatives, and disproportionate rates of chronic conditions [11,12]. Colonias are home to approximately 500,000 people, 96% of whom who identify as Hispanic or Latino/a [13,14,15]. An estimated 23.9% of colonia residents live in poverty, rates which are substantially higher than those of Texas (14.2%) and the U.S. (11.6%) [16]. Few colonias have PA resources like parks and other public spaces for residents to be active [13,17,18]. Research conducted among adults living in colonias suggests low adherence to PA guidelines, with 67.6% of Hispanic respondents who reside in colonias not meeting PA recommendations, compared to 55.6% of Hispanic respondents residing in other locations in the U.S. [19].

Family and cultural values play an important role in health behaviors, including PA. For example, Latino families often report high levels of collectivism and familism [20,21,22,23]. Collectivism is defined as providing financial or social support to one’s familial unit above all else [24]. Similarly, familism is an emphasis on having loyalty and pride in one’s family [25,26]. PA of Mexican-heritage fathers residing in colonias is associated with the number of familial social connections [27], and research on Mexican-heritage sibling dyads shows that younger siblings may emulate the PA behavior of their older siblings [28]. To address increased barriers to PA and rates of chronic conditions in colonias, it is crucial to apply culturally tailored health promotion programs [29,30]. Mexican-heritage child PA is associated with frequency of active play with close social contacts, which can be modified through intervention [31,32]. Hence, applying a family systems approach may improve PA [33,34]. Family systems theory posits that a family functions as a system, wherein people are expected to interact with and respond to one another in certain ways, thus creating family norms and social influence on health behavior [35]. A family systems approach to PA promotion includes increased benefits for PA outcomes compared to individual interventions, likely due to improved role modeling and opportunities [36].

Recent literature on family-centered and culturally adapted PA interventions has shown promising results in various populations (e.g., primary school-aged daughters and preschoolers) [37,38,39], with studies by O’Connor et al. [40,41] and Perez et al. [42] demonstrating the feasibility and acceptability of culturally adapted, father-focused obesity interventions for Hispanic families. Few family-centered programs have included adequate engagement of fathers [43,44]. Recent research has recognized the specific impact of Latino fathers on the health and wellbeing of their children [43,45]. While there have been notable father-focused program implementations (e.g., the “Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids” obesity treatment program in Australia) [46,47], additional research is needed on culturally tailored programs of this kind [41]. Only one study using a family-centered program and incorporating the father’s role in promoting health behaviors has occurred in the U.S. among Mexican-heritage populations [41]. However, this study recruited participants in an urban location where resource access may be higher [41]. Mexican-heritage families in colonias face unique challenges that may impact PA behaviors. These include limited access to safe recreational spaces, cultural beliefs about PA, and socioeconomic barriers [17]. Understanding these contextual factors is crucial for developing effective, tailored interventions for this population.

To fill the gap on engaging fathers in health programs and provide opportunities and resources for PA, the purpose of this article is to report the PA outcomes of the ¡Haz Espacio para Papi! (Make Room for Daddy; HEPP!) culturally tailored, father-focused, and family-centered health promotion program for Mexican-heritage families residing in colonias in south Texas.

2. Materials and Methods

This manuscript reports on PA outcomes from the HEPP! program. Specifically, the HEPP! program was a 6-week, father-focused, family-centered nutrition and PA program for Mexican-heritage families residing in colonias in south Texas along the Lower Rio Grande Valley [48,49,50]. Trained promotora researchers contributed to all elements of this program, including community assessments, program design, implementation, evaluation, and data interpretation [49]. Promotoras (promotoras de salud) are female community health workers who work and live in Latino and Hispanic communities and are actively engaged in coordinating or ensuring health care service provision, health promotion, and outreach [51,52]. In addition to these roles, promotora researchers also serve as research collaborators in community–academic partnerships, receive training in research methods, and are key members of the research team [51,52]. Prior to recruitment, all materials were approved by the referent Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.1. Setting and Participants

Families were recruited from colonias east of Edinburg, Texas, in areas referred to in this study as the San Carlos area. Prior to the program, promotora researchers led formative work within 18 total geographic clusters in Hidalgo County, 12 of which were in the San Carlos area. These 12 were randomized, and the first 5 geographic clusters identified were selected to participate in the HEPP! program. Promotora researchers identified potential participants by completing door-to-door canvassing and recontacting the participants from previous studies who consented to recontact. Eligible families met the following criteria: (1) have no food allergies; (2) have no PA restrictions; (3) have a child 9–11 years of age at time of program enrollment; (4) both parents/partners are at least 21 years of age; (5) at least one parent/grandparent/great-grandparent to child participants are of Mexican origin (i.e., Mexican heritage); (6) both parents prefer to speak, write, and read in Spanish; and (7) both parents actively live/reside in the same household.

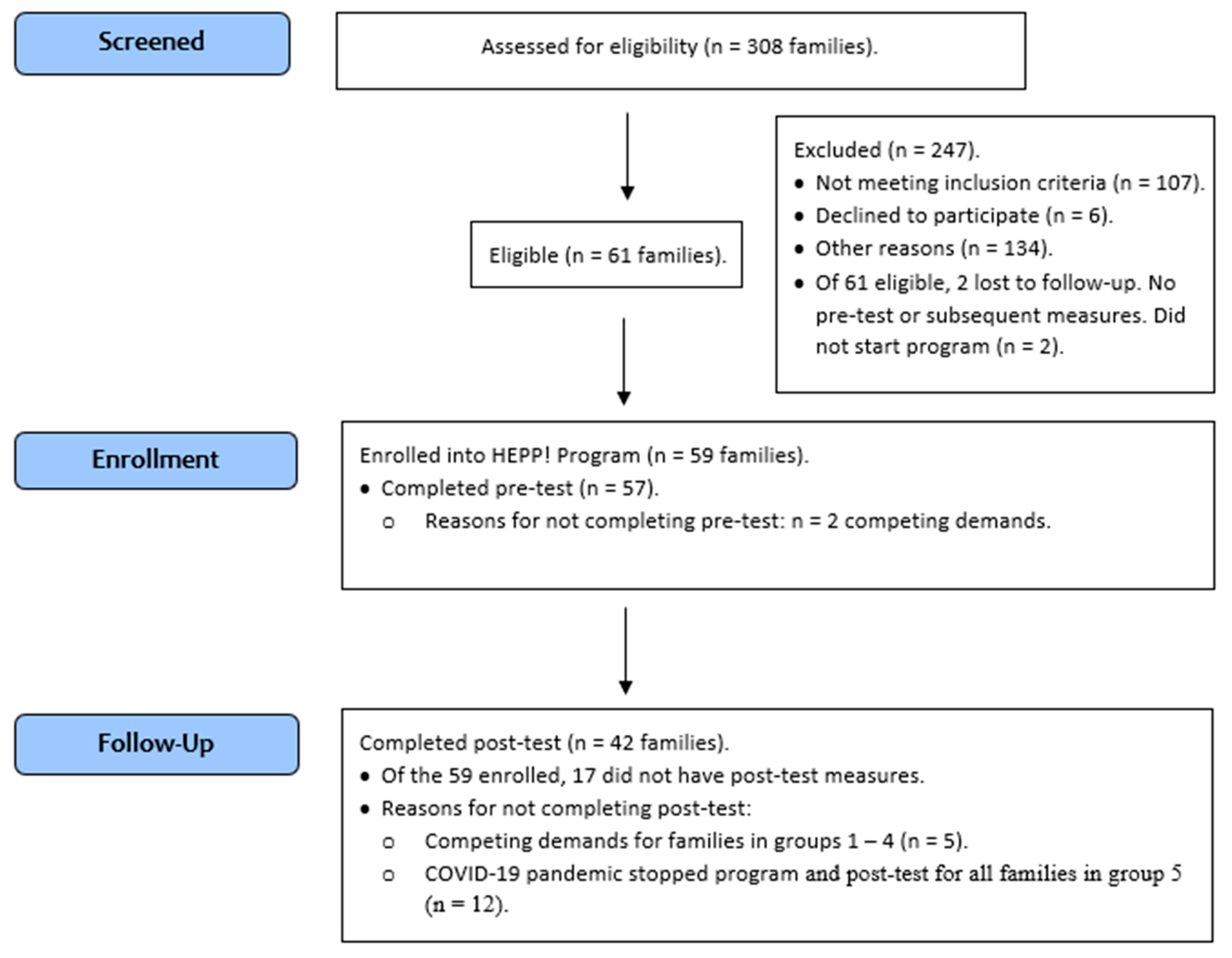

Promotora researchers screened a total of 308 families across 18 geographic clusters in Hidalgo County. These 18 geographic clusters were randomized. Of these 308 families, 59 were enrolled from the first 5 geographic clusters identified. These 59 families completed baseline (pre-test) measures for the father, mother, and child (see Figure 1). Due to logistical constraints (e.g., facility space needing to meet requirements for nutrition and physical activity, personnel) and to allow for deeper one-on-one interactions between program staff and participating families, only one cluster (9–13 families) completed the program at a time, and families were subdivided into smaller groups of 4–6 families for the Saturday morning or afternoon program sessions. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants from recruitment through enrollment, baseline/pre-test, and post-test measures.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Families completed the program between July 2019 and February 2020. Group 1 families (n = 12 families) participated in the program from July 2019–August 2019; Group 2 (n = 10) was from August 2019–September 2019; Group 3 (n = 13) was from October 2019–November 2019; and Group 4 (n = 12) was from November 2019–January 2020 (to adjust for holidays). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes to face-to-face interactions, Group 5’s (n = 12) participation was truncated, and only their control period data are included, since they did not finish the full program as originally designed and only participated in 2 out of the 6 sessions (February 2020). Five additional families withdrew from the program and did not agree to undergo post-test measurements (see Figure 1, Participant Flowchart), and three families did not complete the program, but agreed to undergo post-test measurements, and were subsequently included in analyses. This analytic sample included 59 families who enrolled in the study; of these, 42 families had complete follow-up measures.

2.2. Study Design

Random sampling was used to identify geographic clusters for program participants. Random assignment was not used to allocate families into program and control groups; rather, a modified stepped-wedge, cluster randomized design (quasi-experimental) was used to test program effects between the program and a delayed control, while balancing ethical and practical considerations [53]. Supplementary Information S1 presents the study design.

2.3. ¡Haz Espacio Para Papi! (HEPP!) Program

The objectives of the HEPP! program were to improve dietary intake of fruits and vegetables, increase PA, and enhance family functioning among Mexican-heritage family triads (children, fathers, and mothers) residing in colonias, with a primary focus on children and fathers. A more detailed description of the HEPP! program, PA curriculum, and process evaluation has been published [48,50]. In brief, six weekly sessions were delivered by promotora researchers, held at a local community center, and each lasted roughly 150 min, including all program components (e.g., interactive nutrition and cooking education, PA, family dynamics).

The PA curriculum embraced existing traditions while encouraging new additions to increase active play [48]. For example, several lessons added active variations to traditional games played among Mexican-heritage families. Lessons incorporated modified concepts from SPARK physical education and after school programing [54], and “Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids” [47], with theoretical grounding in the Social Cognitive Theory [55] and Family Systems Theory [35]. Activities were designed to engage the child, father, and mother, but primarily focused on father–child co-participation in light-to-moderate PA. Take-home challenges for the entire family provided continuity between in-person sessions, which were also short in duration, with fun activities. Each week, families were given two at-home challenges to complete between sessions [48].

2.4. Measures

All measures were collected in-person by promotora researchers. Sociodemographic variables were collected at baseline via surveys, and they included age, sex, and country of birth. Surveys were administered in the preferred language of choice (Spanish or English). The intervention dose was measured as the number of sessions attended, and the number of minutes with a PA-focus across all sessions. The number of sessions attended was enumerated using attendance documents, and categorized (0, 1–3, 4–5, or >5 sessions). The total minutes of PA-focused time across all sessions were calculated by adding the planned PA-focused minutes for each session when the family was in attendance. This summed variable was categorized (0, 1–100, or >100 min).

2.4.1. Body Mass Index (BMI)

Height and weight were collected using a HM200P PortStad portable stadiometer and digital scale at baseline. BMI was calculated for adults using height and weight, and it was calculated as BMI = kg/m2, where kg is weight in kilograms and m2 is height in meters squared. BMI categories were determined based on recommended cutoffs [56] for underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 18.5 to <25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). BMI-for-age z-scores for children were calculated according to the 2000 CDC Growth Charts for children ages 0 to <20 years [57]. Overweight was defined as a z-score > +1 SD, and obesity was defined as >+2 SD [58].

2.4.2. Device-Measured Physical Activity

ActiGraph GT9X accelerometers (ActiGraph Corporation, Pensacola, FL, USA) were used to measure daily time spent doing sedentary, light PA (LPA), and moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA). Fathers, mothers, and participating children were asked to wear the accelerometer on their non-dominant wrist 24 h per day for 7 days at three separate timepoints, as follows: (1) at baseline (prior to being enrolled as the “control” arm); (2) during the transition measurements, (6–8 weeks after baseline data collection); and (3) post-intervention (6–8 weeks after the transition timepoint and 12–16 weeks after baseline). Non-wear periods were identified according to the procedures established by Ahmadi et al. [59], which differentiate non-wear periods from sleep. Sleep periods were detected using the algorithm developed by Van Hees et al. [60], while non-wear periods were identified and differentiated from sleep using the methods described by Ahmadi and colleagues [59]. Monitoring days were considered valid if the wear time was greater than 960 min per day [60]. To be included in the analysis, participants were required to have at least four valid monitoring days, with at least one of those days being a weekend day.

Raw accelerometer data collected at 30 Hz were processed into PA metrics using a machine-learned random forest classifier that was specifically designed and validated for assessing PA in school-aged youth [61,62] and free living adults [63]. The classifier for school-aged children uses features in the raw acceleration signal to identify/quantify time spent doing sedentary activities (sitting/lying down); light-intensity activities and games, such as walking and running; and moderate-to-vigorous intensity activities and games [61,62]. The adult random forest model classified movement behaviors as sedentary (lying/sitting still), stationary plus (active sitting/standing, still/active standing), walking, or running [63]. Further information about machine-learning algorithms and their application to accelerometry can be found elsewhere [64]. For children, MVPA was defined as the sum of daily time spent walking, running, and engaging in moderate-to-vigorous activities and games, and LPA was defined as the sum of daily time spent doing light-intensity activities and games. For adults, MVPA was defined as the sum of daily time spent walking and running, and LPA was defined as stationary plus. MVPA minutes and sedentary minutes were then averaged across all valid wear days to produce summary measures of the mean MVPA minutes per day and the mean sedentary minutes per day for each participant.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data analyses were conducted with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, proportions, and means, were calculated for all baseline sociodemographic, health, and program (e.g., intervention dose) variables in the total sample. Sociodemographic and health variables were compared across groups using analysis of variance tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics were used to quantify program participation (e.g., intervention dose) and report mean within-person PA and sedentary behavior changes of children, fathers, and mothers for each subpopulation as a whole, and by randomized group assignment, for both control and intervention periods.

To determine the overall effect of the intervention, statistical analyses of the intervention effect for each outcome variable, daily minutes of MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior for the child, father, and mother were conducted using linear mixed models (PROC MIXED, SAS 9.4). Models account for the hierarchical structure of the data, are recommended for use with stepped-wedge cluster designs [53,65], and allow for the analysis of partial datasets with dropouts or missing study visits. Analyses followed intention-to-treat principles [65,66]. In each model, we included a fixed effect for each scheduled time step in the design [53,65].

Modeling the random effects and correlation structure included an analysis of the best model fit for the observed correlations in the data and the overall model fit using information criteria (AIC, BIC) [67]. Random effects for the assigned study group were included in the model to account for non-independence of members in the same intervention group as either a random intercept or random slope. For all outcomes, when both random effects were included, one estimated variance parameter was zero. We included non-independent covariance structures at the subject level to account for repeated measurements on the same individuals. An unstructured correlation was optimal for outcomes with different variance estimates for each time point and different covariances between time points. For all other outcomes, a model with fewer parameters was chosen. Modeling choices were conservative to include retaining outliers in a few instances. Models were all assessed for adequacy and appropriateness of model assumptions.

Figures were created to visualize the group-level mean MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior at each data collection time point. Student’s t-tests were used to determine the statistical significance (at the α = 0.05 level) of group change in MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior.

3. Results

Table 1 provides descriptive characteristics of the study sample. In total, 59 families participated in this study. Across all groups, the mean ages were 10.1 years (SD = 0.9) for children, 39.9 years (SD = 8.2) for fathers, and 36.2 years (SD = 6.2) for mothers. In the total sample, 36.2% of children had a healthy BMI-for-age, 32.8% had an overweight BMI-for-age, and 31.0% had an obese BMI-for-age. Approximately half (52.5%) of the children were female. Many fathers (48.3%) and most mothers (65.5%) were obese (BMI ≥ 30) at baseline. There were no significant differences in the BMI for children, fathers, or mothers across groups. Before the intervention, on average, children spent 50.6 min (±17.8) in daily MVPA, 230.2 min (±55.7) in daily LPA, and 619.5 min (±62.5) in daily sedentary behavior; fathers spent 75.1 min (±35.7) in daily MVPA, 547.7 min (±98.4) in LPA, and 373.2 min (±91.5) in daily sedentary behavior.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Families, for Total Sample and by Group Assignment.

Approximately 52.5% (n = 31) of families attended all six program sessions; 6.8% (n = 4) attended four to five, 3.4% (n = 2) attended three, 22% (n = 13) attended one to two, and 15.3% (n = 9) attended no sessions. Every session included PA activities, with PA curriculum implemented for an average of 22 min (SD = 15.31) each week (sessions 1–3 and 5: 13 min each; session 4: 50 min; and session 6: 30 min) [48]. Approximately 78.0% (n = 46) of families received 100–132 min of PA-specific programming, 15.2% (n = 9) received 1–99 min, and 6.8% (n = 4) received 0 min. Table 2 describes the program effects on MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior. For children, there were no significant changes in MVPA (p = 0.18), LPA (p = 0.52), or sedentary behavior (p = 0.74). For fathers, there were no significant changes in MVPA (p = 0.94), LPA (p = 0.17), or sedentary behavior (p = 0.15). For mothers, there was a significant decrease in LPA (p < 0.01) and no significant changes in MVPA (p = 0.66) or sedentary behavior (p = 0.77). Specifically, the program resulted in an average reduction of 23.2 min of LPA among mothers (95% CI: −34.0, −12.4). Table 2 also displays the overall effects on MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior after controlling for the number of sessions attended and the number of PA minutes across all attended sessions. After adjustment, findings were consistent with unadjusted models and showed that mothers’ LPA was the only statistically significant outcome impacted by the program. Specifically, the program resulted in an average reduction of 23.1 min (p = 0.01) of LPA among mothers after adjusting for the number of sessions attended, and an average reduction of 26.2 min (p = 0.02) of LPA among mothers after adjusting for the number of PA minutes across sessions.

Table 2.

Trial Effects on Child, Father, and Mother’s Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity (MVPA), Light Physical Activity (LPA), and Sedentary Behavior Daily Minutes.

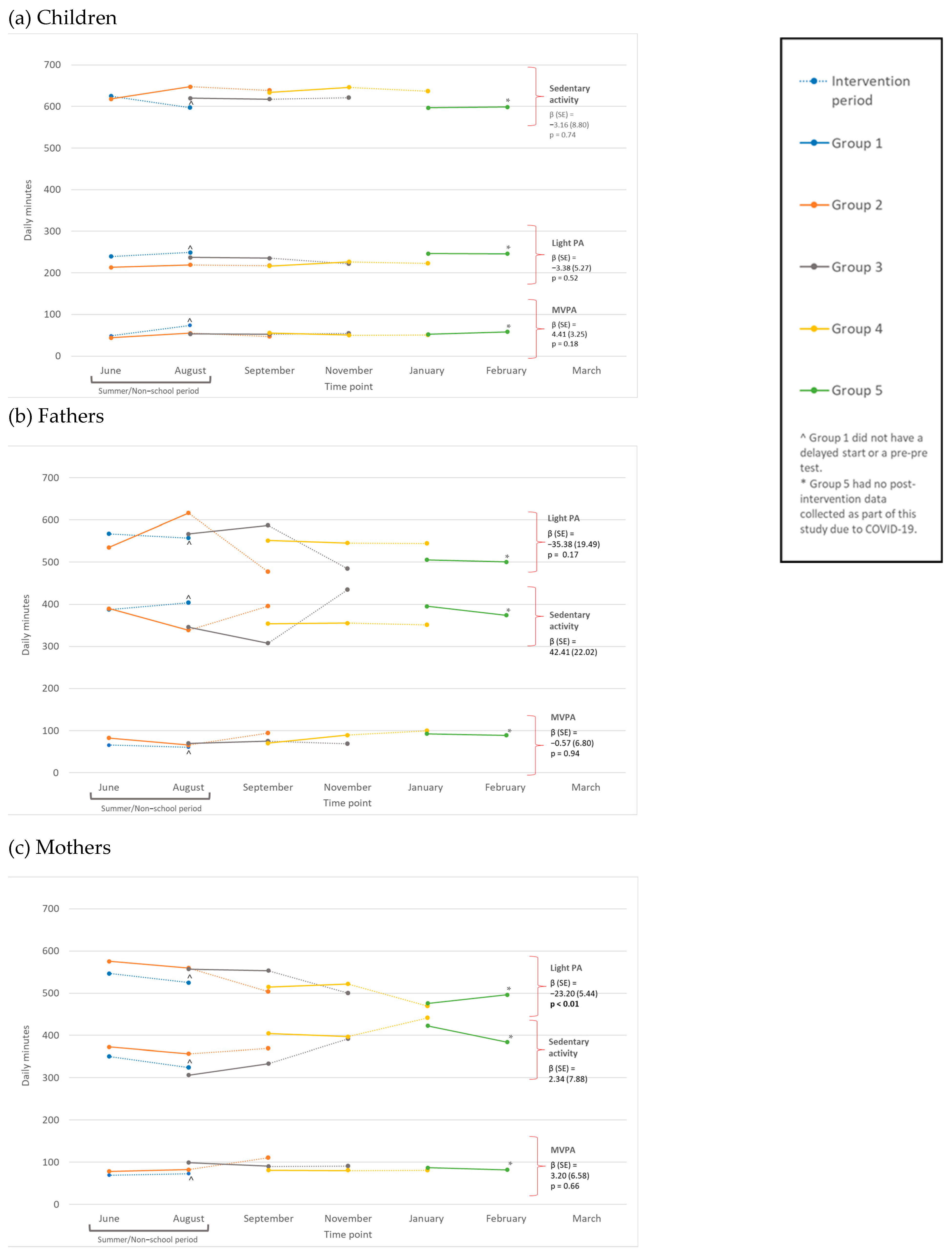

Figure 2a displays changes in daily minutes of MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior for children in each study group. Group 1, which received the program during summer/non-school months (unlike other groups), showed non-significant trends for child sedentary behavior during the program, significant increasing trends for MVPA (p < 0.05), and non-significant trends for LPA. Group 2 showed significant decreasing trends for child MVPA (p < 0.05), and non-significant trends for LPA and sedentary behavior. Group 3 showed non-significant trends for children’s LPA and increasing trends for MVPA and sedentary behavior. Group 4 showed non-significant trends for children’s LPA and sedentary behavior, and almost no changes in MVPA. For more information, see Supplementary Information S2.

Figure 2.

Group-level trial effects on (a) children, (b) fathers, and (c) mothers’ moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), light PA (LPA), and sedentary daily minutes. (b) Displays changes in daily minutes of MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior for fathers in each study group. Group 1, who participated in the program during summer/non-school months (unlike other groups), showed non-significant trends for fathers’ MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior. Group 2 showed significant decreasing trends for fathers’ LPA and significant increasing trends for MVPA and sedentary behavior (p < 0.05). Group 3 showed non-significant trends for fathers’ MVPA and LPA, and significant increasing trends for sedentary behavior (p < 0.05). Group 4 showed non-significant trends for fathers’ LPA and sedentary behavior and increasing trends for MVPA. For more information, see Supplementary Information S3.

Figure 2c displays changes in the daily minutes of MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior for mothers in each study group. Group 1, who participated in the program during summer/non-school months (unlike other groups), showed non-significant trends for mothers’ LPA, MVPA, and sedentary behavior. Group 2 showed non-significant trends for mothers’ LPA and sedentary behavior, and significant increasing trends for MVPA (p < 0.05). Groups 3 and 4 showed non-significant trends for mothers’ LPA, MVPA, and sedentary behavior. For more information, see Supplementary Information S4.

4. Discussion

This study described PA and sedentary behavior outcomes for participating Mexican-heritage children, fathers, and mothers in a family-centered, father-focused program titled ¡Haz Espacio para Papi! (Make Room for Daddy). This paper evaluated program effects on MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior. In doing so, this study fills an important gap in the literature on father-focused and family-centered PA programs. Overall, the results demonstrated that the PA program components had no significant, positive impact on MVPA, LPA, or sedentary behavior among children, fathers, or mothers. Although mothers, who engaged in only half of the sessions, as designed (sessions 1, 2, 4; totaling 76 min of PA-focused program time) [48], saw a significant change in LPA from baseline to post-assessment, the effect was negative.

While this study did not show an overall, significant intervention effect on MVPA, LPA, or sedentary behavior outcomes for participants, comparisons between our findings and past research can elucidate reasons for null effects. Past interventions that focused on Hispanic or Mexican-heritage individuals by providing access to, or referrals for, PA resources (in addition to educational materials) showed larger effects [68]. For our study, the program might have been limited in its impact on PA outcomes over time among participants with low access to PA resources, which is shown to be necessary for maintaining regular PA within colonias neighborhoods [17]. In addition, community-based interventions have effectively increased walking and decreased depression and stress among Hispanic or Mexican-heritage participants, so it may be that programs focused less on the nuclear family unit and more on larger social networks may be more effective [68,69]. Lastly, this PA program was included as part of a larger program that addressed healthy eating behavior. Past research in this field has largely examined independent PA interventions [68,70,71]. Given the time needed to address healthy eating and cooking demonstrations in the HEPP!, it is likely that the dose of PA instruction and programming (i.e., a total of 132 min across 6 weeks, 14.67% of the total intervention time, where four sessions only had 13 min of PA programming) was too small to have a significant effect.

One program that shows many similarities to the intervention presented in this paper is the “Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids” (HDHK) program developed in Australia, which significantly increased child PA for white fathers and children [47,72]. Results from HDHK-based programs have demonstrated significant PA impacts, which differs from our study results [40,42,69,70,71,72]. To note, HDHK in Australia and as applied in Houston, U.S., sampled fathers or children that were experiencing an overweight or obese weight status at enrollment, so it may be that this type of intervention only yields significant behavioral impact when recruiting participants with low rates of PA and healthy eating at baseline [40,42,69,70,71,72]. Our study did not implement eligibility criteria related to weight status, but 88.0% of fathers and 63.8% of children were overweight or obese in our study population. In addition, HDHK studies showed a higher dose of PA program components than the HEPP!, ranging from seven total face-to-face sessions (90 min/session, 630 min total contact time) [46] to eight total face-to-face sessions (75 min/session, 600 min total contact time) with fathers [47], and a total of 225–270 total PA minutes (e.g., rough and tumble play, fun fitness circuits, and active games). In HEPP!’s six-session program (150 min/session, 900 min total contact time), four sessions (one, two, three, and five) included 13 min of PA; session four included 50 min of PA, and session six included 30 min of PA (total practical PA time = 132 min). Additional contact time focused on cooking demonstrations, healthy eating, and enhancing family dynamics. In addition, HEPP! included 6 weeks of intervention and follow-up measurements at 6 weeks, compared to 7 and 8 weeks of intervention and follow-up measurements at 14 and 24 weeks, as done in the two HDHK studies [46,47,73,74].

Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size for the study was small, which limited our ability to study group-level intervention outcomes. Therefore, our results are not generalizable to the broader population of Mexican-heritage families living in colonias. It should also be noted that this study employed all-female implementation team members (promotoras). It is possible that fathers could experience more program connection and engagement with male implementers (promotores), which should be considered in future programs. Challenges with participant retention, compliance with the intervention plan, and missing participant data should be considered when interpreting results from this study. Data from the process evaluation, previously reported, show that 24.2% of families did not engage in the weekly take-home challenges for PA [48]. Lastly, we did not measure environmental factors that may influence long-term impacts, such as access to PA resources or neighborhood safety [75,76]. Future research should assess and account for differences in access to safe PA spaces.

This study also has strengths. First, HEPP! is a theory-informed program that incorporates family and culturally inclusive elements. To date, no existing research has implemented a father-focused and family-centered PA program among Mexican-heritage residents of colonias to address low levels of PA among children and adults [19]. Second, we used accelerometers to measure PA, which addresses bias that is often present in research using self-reported measures of PA among children and adults [77]. Lastly, we used a modified stepped-wedge design to maximize the benefit to participating families and reduce resources needed to provide the program, while also providing a control group. Similar study designs should be considered in future research to ensure that positive impacts of health programs are accessible to all participants, in turn, potentially improving community acceptance of the program [53].

5. Conclusions

These study findings have important research implications. First, since past research shows that family-based interventions can increase father–child bonding and behavior reinforcement [43,46,47], future research should examine whether social (e.g., social support) and self-regulatory (e.g., self-efficacy, skill competency) outcomes are the mechanisms through which the program influences PA [78]. Second, additional research is needed to investigate the impact of family-centered interventions on replacement activity to understand whether the intervention increases PA or simply replaces existing PA behaviors with new ones. Third, research is needed that increases the dose of PA interventions and has longer follow-up periods to understand whether HEPP! can positively impact PA. Examinations of dose response within PA interventions like HEPP! may be needed to determine the optimal duration and frequency for such family-centered father-focused programs. Finally, future research on the impact of family-centered interventions should quantify and account for PA barriers that fathers and families face (e.g., time constraints) [73,74]. While PA barriers were measured in our study, they were collected in an open-ended qualitative format which did not allow for statistical adjustment.

This study has additional implications for public health practice. Although we presented models adjusting for the number of sessions attended and the number of minutes of PA-focus across all sessions, and saw no differences compared to unadjusted models, null findings may indicate that the overall dose of PA components was too small (max PA-focused minutes = 132 min across six sessions). Future family-centered programs should consider increasing the dose of PA-focused components when coupled with healthy eating strategies by implementing PA components for a longer duration within program sessions, running the program for longer periods of time (e.g., >3 months), as well as increasing follow-up periods (e.g., >1 year) to assess potential long-term changes [46,47,68]. Evaluating the necessary dose for both PA and healthy eating components, when paired with a family-centered approach, should be prioritized. Next, integrating cultural needs and preferences of the priority population are crucial, especially when low-income groups or communities experiencing marginalization are being engaged. Family-centered programming, based on a promotora model, showed promise in supporting Mexican-heritage families in a marginalized community. Future programming efforts should apply approaches, curricula, or strategies to tailor programs for underserved populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph21111475/s1, Figure S1. Visualization of the ¡Haz Espacio para Papi! (HEPP!) Stepped-Wedge Study Design. Table S1: Participation and outcome characteristics of children, for all children and by group assignment. Table S2: Participation and outcome characteristics of fathers, for all fathers and by group assignment. Table S3. Participation and outcome characteristics of mothers, for all mothers and by group assignment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.U.M. and J.R.S.; design, M.R.U.M., J.R.S., C.M.J., T.P. and L.G.; data acquisition, L.G., H.D., T.P. and C.M.J.; data analysis, R.X.S., K.R.Y., M.E.W. and S.G.T.; data interpretation, M.R.U.M., T.P., M.E.W., K.R.Y. and R.X.S.; drafted the work, M.R.U.M., T.P., M.E.W., K.R.Y. and R.X.S.; substantively revised the work, M.R.U.M., T.P., M.E.W., K.R.Y., J.R.S., R.X.S., S.G.T., C.M.J., L.G. and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award #2015-68001-23234. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In addition, the funding body was not involved in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or the writing of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt (IRB 2019-0750).

Informed Consent Statement

Written consent and assent were obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the work, dedication, and expertise provided by Patsy Gonzales, Lucy Briones, Elvira Reyes Martínez, Iris Vazquez, Tracy Gómez, and the Salud para Usted y Su Familia (SPUSF, Health for You and Your Family) program teams throughout the project and during the ¡Haz Espacio para Papi! (HEPP, Make Room for Daddy!) HEPP! Program at the Texas A&M School of Public Health, Baylor University, and New Mexico State University; the community partners, including the following three community advisory boards in South Texas: the Progreso Community Health Advisory Council (P-CHAC) in Progreso, the Advisory Committee for Health and Community (CASCO) in San Juan, and the Hand-in-Hand in San Carlos (HHSC); and all families who participated in SPUSF and HEPP!.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

References

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, K.E.; King, A.C.; Buchner, D.M.; Campbell, W.W.; DiPietro, L.; Erickson, K.I.; Hillman, C.H.; Jakicic, J.M.; Janz, K.F.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; et al. The scientific foundation for the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kann, L.; McManus, T.; Harris, W.A.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Queen, B.; Lowry, R.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; Thornton, J.; et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill. Summ 2018, 67, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Liu, B.; Sun, Y.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Wallace, R.B.; Bao, W. Trends in adherence to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans for aerobic activity and time spent on sedentary behavior among US adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e197597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D.L.; Clarke, T.C. State variation in meeting the 2008 federal guidelines for both aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities through leisure-time physical activity among adults aged 18–64: United States, 2010–2015. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2018, 112, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 2nd Edition. 2018. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/physical-activity-guidelines/current-guidelines (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Jilcott, S.B.; Evenson, K.R.; Laraia, B.A.; Ammerman, A.S. Association between physical activity and proximity to physical activity resources among low-income, midlife women. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2007, 4, A04. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1832127/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Bancroft, C.; Joshi, S.; Rundle, A.; Hutson, M.; Chong, C.; Weiss, C.C.; Genkinger, J.; Neckerman, K.; Lovasi, G. Association of proximity and density of parks and objectively measured physical activity in the United States: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 138, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Floyd, M.F.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Saelens, B.E. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2012, 125, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisel, D.B. Vulnerable populations in healthcare. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2013, 26, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, R.L.; Olson, T.; Robinson, K.; Wiebe, J.; DiGregorio, R.; Guillermina, M.; Albrechtsen, J.; Bean, N.H.; Ortiz, M. A health survey of a colonia located on the west Texas, US/Mexico border. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2010, 12, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.; Ryder Perlmeter, E.; Sobel-Blum, E.; Marquez, R. Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas-Mexico Border; Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas: Dallas, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, P.M. Colonias and Public Policy in Texas and Mexico: Urbanization by Stealth; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Parcher, J.W.; Humberson, D.G. Using GIS to assess priorities of infrastructure and health needs of “colonias” along the United States-Mexico border. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2009, 8, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey Data. 2011. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/developers/data-sets/acs-5year/2011.html (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Sharkey, J.R.; Patterson, M.S.; Dean, W.R. Understanding contextual barriers, supports, and opportunities for physical activity among Mexican-origin children in Texas border colonias: A descriptive study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Las Colonias in the 21st Century: Progress Along the Texas-Mexico Border. 2015. Available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/cd/pubs/lascolonias.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Bautista, L.; Reininger, B.; Gay, J.L.; Barroso, C.S.; McCormick, J.B. Perceived barriers to exercise in Hispanic adults by level of activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.R.; Crano, W.D.; Quist, R.; Burgoon, M.; Alvaro, E.M.; Grandpre, J. Acculturation, familism, parental monitoring, and knowledge as predictors of marijuana and inhalant use in adolescents. Psychol. Addict. Behav. J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2004, 18, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, L.A. Individualism, collectivism, and cultural compatibility: Implications for counselors and teachers. J. Humanist. Educ. Dev. 1998, 36, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescano, C.M.; Brown, L.K.; Raffaelli, M.; Lima, L.-A. Cultural factors and family-based HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeff, C.; Greenfield, P.M.; Quiroz, B. Conceptualizing interpersonal relationships in the cultural contexts of individualism and collectivism. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2000, 2000, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Tseng, V.; Lam, M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Dev. 1999, 70, 1030–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal, F.; Marín, G.; Otero-Sabogal, R.; Marín, B.V.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidel, A.G.L.; Contreras, J.M. A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2016, 25, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, T.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Patterson, M.S.; McClendon, M.E.; Gómez, L.; Trost, S.G.; Sharkey, J. Papás Activos: Associations between physical activity, sedentary behavior and personal networks among fathers living in Texas colonias. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylitalo, K.R.; Bridges, C.N.; Gutierrez, M.; Sharkey, J.R.; Meyer, M. Sibship, physical activity, and sedentary behavior: A longitudinal, observational study among Mexican-heritage sibling dyads. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satcher, D. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.A.; Coombe, C.M.; Cheezum, R.R.; Schulz, A.J.; McGranaghan, R.J.; Lichtenstein, R.; Reyes, A.G.; Clement, J.; Burris, A. Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, T.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Patterson, M.S.; Meyer, A.; Talbert, T.; Sharkey, J. Active play social network change for Mexican-heritage children participating in a father-focused health program. Am. J. Health Educ. 2022, 53, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, T.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Patterson, M.S.; Trost, S.G.; Gómez, L.; Sharkey, J. Active play network influences on physical activity among children living in Texas colonias. Fam. Commun. Health 2021, 44, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung-Chan, P.; Sung, Y.; Zhao, X.; Brownson, R. Family-based models for childhood-obesity intervention: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, H.M.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Mesman, J.; van der Veek, S. Interventions aimed at reducing obesity in early childhood: A meta-analysis of programs that involve parents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, C.B. Understanding Family Process: Basics of Family Systems Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman-Ulrich, H.; Wilson, D.K.; St George, S.M.; Lawman, H.; Segal, M.; Fairchild, A. The integration of a family systems approach for understanding youth obesity, physical activity, and dietary programs. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 13, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Young, M.D.; Barnes, A.T.; Eather, N.; Pollock, E.R.; Lubans, D.R. Engaging fathers to increase physical activity in girls: The “dads and daughters exercising and empowered” (DADEE) randomized controlled trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, L.M.; Rayward, A.T.; Pollock, E.R.; Kennedy, S.-L.; Young, M.D.; Eather, N.; Barnes, A.T.; Lee, D.R.; Morgan, P.J. Twelve-month outcomes of a community-based, father-daughter physical activity program delivered by trained facilitators. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P.J.; Grounds, J.A.; Ashton, L.M.; Collins, C.E.; Barnes, A.T.; Pollock, E.R.; Kennedy, S.L.; Rayward, A.T.; Saunders, K.L.; Drew, R.J.; et al. Impact of the ‘Healthy Youngsters, Healthy Dads’ program on physical activity and other health behaviours: A randomised controlled trial involving fathers and their preschool-aged children. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Beltran, A.; Musaad, S.; Perez, O.; Flores, A.; Galdamez-Calderon, E.; Isbell, T.; Arredondo, E.M.; Parra Cardona, R.; Cabrera, N.; et al. Feasibility of targeting Hispanic fathers and children in an obesity intervention: Papás Saludables Niños Saludables. Child Obes. 2020, 16, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Perez, O.; Beltran, A.; Colón García, I.; Arredondo, E.; Parra Cardona, R.; Cabrera, N.; Thompson, D.; Baranowski, T.; Morgan, P.J. Cultural adaptation of ‘Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids’ for Hispanic families: Applying the ecological validity model. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Perez, O.; Beltran, A.; Colón García, I.; Arredondo, E.; Parra Cardona, R.; Cabrera, N.; Thompson, D.; Baranowski, T.; Morgan, P.J. Papás Saludables, Niños Saludables: Perspectives from Hispanic parents and children in a culturally adapted father-focused obesity program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Young, M.D.; Lloyd, A.B.; Wang, M.L.; Eather, N.; Miller, A.; Murtagh, E.M.; Barnes, A.T.; Pagoto, S.L. Involvement of fathers in pediatric obesity treatment and prevention trials: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.; Hennessy, E.; McSpadden, K.; Oh, A. Parenting styles and practices in children’s obesogenic behaviors: Scientific gaps and future research directions. Child Obes. 2013, 9, S73–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Bradley, R.H. Latino fathers and their Ccildren. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Callister, R.; Burrows, T.; Fletcher, R.; Okely, A.D.; Young, M.D.; Miller, A.; Clay, V.; et al. The ‘Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids’ community effectiveness trial: Study protocol of a community-based healthy lifestyle program for fathers and their children. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Callister, R.; Okely, A.D.; Burrows, T.L.; Fletcher, R.; Collins, C.E. The ‘Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids’ randomized controlled trial: Efficacy of a healthy lifestyle program for overweight fathers and their children. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochnow, T.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Johnson, C.; Delgado, H.; Gomez, L.; Sharkey, J. The development and pilot testing of the ¡Haz Espacio para Papi! program physical activity curriculum for Mexican-heritage fathers and children. Am. J. Health Educ. 2021, 52, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Allicock, M.A.; Sharkey, J.R.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Gómez, L.; Prochnow, T.; Laviolette, C.; Beltrán, E.; Garza, L.M. Promotoras de salud in a father-focused nutrition and physical activity program for border communities: Approaches and lessons learned from collaboration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.M.; Sharkey, J.R.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Gómez, L.; Allicock, M.A.; Prochnow, T.; Beltrán, E.; Martinez, L. Designing for multilevel behavior change: A father-focused nutrition and physical activity program for Mexican-heritage families in South Texas border communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St John, J.A.; Johnson, C.M.; Sharkey, J.R.; Dean, W.R.; Arandia, G. Empowerment of promotoras as promotora–researchers in the Comidas Daludables & Gente Sana en las Colonias del Sur de Tejas (Healthy Food and Healthy People in South Texas Colonias) program. J. Prim. Prev. 2013, 34, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.M.; Sharkey, J.R.; Dean, W.R.; St John, J.A.; Castillo, M. Promotoras as research partners to engage health disparity communities. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, M.A.; Hughes, J.P. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2007, 28, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Rosengard, P.; Ballard, K. The SPARK programs: A public health model of physical education research and dissemination. J. Teach. Physl. Educ. 2016, 35, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bmi/adult-calculator/bmi-categories.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The SAS Program for CDC Growth Charts That Includes the Extended BMI Calculations. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/growth-chart-training/hcp/computer-programs/sas.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. BMI-for-Age (5–19 years) n.d. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/bmi-for-age (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ahmadi, M.N.; Nathan, N.; Sutherland, R.; Wolfenden, L.; Trost, S.G. Non-wear or sleep? Evaluation of five non-wear detection algorithms for raw accelerometer data. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hees, V.T.; Sabia, S.; Anderson, K.N.; Denton, S.J.; Oliver, J.; Catt, M.; Abell, J.G.; Kivimäki, M.; Trenell, M.I.; Singh-Manoux, A. A novel, open access method to assess sleep duration using a wrist-worn accelerometer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.K.; Tjondronegoro, D.; Chandran, V.; Trost, S.G. Ensemble methods for classification of physical activities from wrist accelerometry. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trost, S.G.; Ahmadi, M.N.; Pfeiffer, K. A novel two-step algorithm for estimating energy expenditure from wrist accelerometer data in youth. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Ambulatory Monitoring of Physical Activity and Movement, Bethesda, MD, USA, 21 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pavey, T.G.; Gilson, N.D.; Gomersall, S.R.; Clark, B.; Trost, S.G. Field evaluation of a random forest activity classifier for wrist-worn accelerometer data. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, A.; Desai, F.; Stewart, T.; Duncan, S.; Mackay, L. Application of raw accelerometer data and machine-learning techniques to characterize human movement behavior: A systematic scoping review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 360–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemming, K.; Haines, T.P.; Chilton, P.J.; Girling, A.J.; Lilford, R.J. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: Rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015, 350, h391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, C.E. Understanding the intention-to-treat principle in randomized controlled trials. West J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 18, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, G.; Molenberghs, G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ickes, M.J.; Sharma, M. A Systematic review of physical activity interventions in Hispanic adults. J. Environ. Public Health 2012, 2012, 156435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mier, N.; Tanguma, J.; Millard, A.V.; Villarreal, E.K.; Alen, M.; Ory, M.G. A pilot walking program for Mexican-American women living in colonias at the border. Am. J. Health Promot. 2011, 25, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, G.; Andermo, S.; Nordenfelt, A.; Lidin, M.; Hellénius, M.L. Effectiveness of a family intervention to increase physical activity in disadvantaged areas-A Healthy Generation, A controlled pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhao, G.; Tan, H.; Wu, H.; Fu, J.; Sun, S.; Lv, W.; He, Z.; Hu, Q.; Quan, M. Effects of family intervention on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children aged 2.5–12 years: A meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 720830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.B.; Lubans, D.R.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Collins, C.E.; Morgan, P.J. Maternal and paternal parenting practices and their influence on children’s adiposity, screen-time, diet and physical activity. Appetite 2014, 79, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.E.; Atkin, A.J.; Panter, J.; Wong, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.; van Sluijs, E.M. Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: A systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouter, A.C.; Davis, K.D.; Updegraff, K.; Delgado, M.; Fortner, M. Mexican American fathers’ occupational conditions: Links to family members’ psychological adjustment. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Sallis, J.F.; Kerr, J.; Lee, S.; Rosenberg, D.E. Neighborhood environment and physical activity among youth a review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdinand, O.A.; Sen, B.; Rahurkar, S.; Engler, S.; Menachemi, N. The relationship between built environments and physical activity: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e7–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taber, D.R.; Stevens, J.; Murray, D.M.; Elder, J.P.; Webber, L.S.; Jobe, J.B.; Lytle, L.A. The effect of a physical activity intervention on bias in self-reported activity. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Social Cognitive Theory. APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol 1: Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).