Factors Associated with Late Antenatal Initiation among Women in Malawi

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Conceptual Framework

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Variables

2.4.1. Dependent Variable

2.4.2. Independent Variables

2.5. Analysis

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Association of Late Uptake of ANC and Participants’ Characteristics

3.3. Determinants of Late ANC Initiation in Malawi

4. Discussion

5. Strength and Weaknesses of the Study

6. Implications for Policy and Clinical Practice

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANC | Antenatal care |

| AOR | Adjusted odds ratios |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DHS | Demographic and Health Survey |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| ICF | Inner City Fund |

| IEC | Information, Education and Communication |

| MDHS | Malawi Demographic and Health Survey |

| MMR | Maternal Mortality Ratio |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Atuoye, K.N.; Amoyaw, J.A.; Kuuire, V.Z.; Kangmennaang, J.; Boamah, S.A.; Vercillo, S.; Antabe, R.; McMorris, M.; Luginaah, I. Utilisation of skilled birth attendants over time in Nigeria and Malawi. Glob. Public Health 2017, 12, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Office (NSO); ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 1992; NSO: Zomba, Malawi; ICF Macro: Rockville, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office (NSO); ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2000; NSO: Zomba, Malawi; ICF Macro: Rockville, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office (NSO); ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004; NSO: Zomba, Malawi; ICF Macro: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office (NSO); ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010; NSO: Zomba, Malawi; ICF Macro: Rockville, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–2016; National Statistical Office: Zomba, Malawi, 2016.

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2023: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Palamuleni, M.E. Prevalence, Trends, and Determinants of at Least Four Antenatal Visits in Malawi: Analyses of the Malawi Demographic and Health Surveys 1992–2016. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2022, 30, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, S.J.; Ndombi, G.O.; Nam, E.W. The impact of the interventions for 4+ antenatal care service utilization in the democratic republic of congo: A decision tree analysis. Ann. Glob. Health 2019, 85, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poma, P.A. Effect of prenatal care on infant mortality rates according to birth-death certificate files. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1999, 91, 515. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe, G.F.; Alie, M.S.; Girma, D.; Mankelkl, G.; Berchedi, A.A.; Negesse, Y. Determinants of early initiation of first antenatal care visit in Ethiopia based on the 2019 Ethiopia mini-demographic and health survey: A multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwimana, G.; Elhoumed, M.; Gebremedhin, M.A.; Nan, L.; Zeng, L. Determinants of timing, adequacy and quality of antenatal care in Rwanda: A cross-sectional study using demographic and health surveys data. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, R.K.; Singh, P.K.; Kumar, C.; Singh, L. Factors associated with the utilization of maternal health care services among adolescent women in Malawi. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2013, 32, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng’ambi, W.F.; Collins, J.H.; Colbourn, T.; Mangal, T.; Phillips, A.; Kachale, F.; Mfutso-Bengo, J.; Revill, P.; Hallett, T.B. Socio-demographic factors associated with early antenatal care visits among pregnant women in Malawi: 2004–2016. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaya, S.; Bishwajit, G.; Shah, V. Wealth, education and urban–rural inequality and maternal healthcare service usage in Malawi. BMJ Glob. Health 2016, 1, e000085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Etowa, J.; Ghose, B.; Tang, S.; Ji, L.; Huang, R. Association between mass media use and maternal healthcare service utilisation in Malawi. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimatiro, C.S.; Hajison, P.; Chipeta, E.; Muula, A.S. Understanding barriers preventing pregnant women from starting antenatal clinic in the first trimester of pregnancy in Ntcheu District-Malawi. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funsani, P.; Jiang, H.; Yang, X.; Zimba, A.; Bvumbwe, T.; Qian, X. Why pregnant women delay to initiate and utilize free antenatal care service: A qualitative study in theSouthern District of Mzimba, Malawi. Glob. Health J. 2021, 5, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.M. A Behavioral Model of Families’ Use of Health Services; Center for Health Administration Studies: Chicago, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirshfield, S.; Downing, M.J., Jr.; Horvath, K.J.; Swartz, J.A.; Chiasson, M.A. Adapting Andersen’s behavioral model of health service use to examine risk factors for hypertension among US MSM. Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaba, E.A.; Afaya, A. Correlates of late initiation and underutilisation of the recommended eight or more antenatal care visits among women of reproductive age: Insights from the 2019 Ghana Malaria Indicator Survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chewe, M.M.; Muleya, M.C.; Maimbolwa, M. Factors associated with late antenatal care booking among pregnant women in Ndola District, Zambia. Afr. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2016, 10, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somé, A.; Baguiya, A.; Coulibaly, A.; Bagnoa, V.; Kouanda, S. Prevalence and factors associated with late first antenatal care visit in Kaya Health District, Burkina Faso. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2020, 24, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sinyange, N.; Sitali, L.; Jacobs, C.; Musonda, P.; Michelo, C. Factors associated with late antenatal care booking: Population based observations from the 2007 Zambia demographic and health survey. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 25, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, R.; Mohammadnezhad, M.; Khan, S. Characteristics and Predictors of Late Antenatal Booking Among Pregnant Women in Fiji. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbamigbe, A.F.; Olaseinde, O.; Fagbamigbe, O.S. Timing of first antenatal care contact, its associated factors and state-level analysis in Nigeria: A cross-sectional assessment of compliance with the WHO guidelines. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrekidan, K.; Worku, A. Factors associated with late ANC initiation among pregnant women in select public health centers of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Unmatched case–control study design. Pragmatic Obs. Res. 2017, 8, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Y.R.; Jha, T.; Mehata, S. Timing of first antenatal care (ANC) and inequalities in early initiation of ANC in Nepal. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramotsababa, M.; Setlhare, V. Late registration for antenatal care by pregnant women with previous history of caesarean section. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2021, 13, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzi, A.; Munyaneza, F.; Mujawase, F.; Banamwana, L.; Sayinzoga, F.; Thomson, D.R.; Ntaganira, J.; Hedt-Gauthier, B.L. Assessing predictors of delayed antenatal care visits in Rwanda: A secondary analysis of Rwanda demographic and health survey 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlandu, C.; Matsena-Zingoni, Z.; Musenge, E. Trends and determinants of late antenatal care initiation in three East African countries, 2007–2016: A population based cross-sectional analysis. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alem, A.Z.; Yeshaw, Y.; Liyew, A.M.; Tesema, G.A.; Alamneh, T.S.; Worku, M.G.; Teshale, A.B.; Tessema, Z.T. Timely initiation of antenatal care and its associated factors among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: A multicountry analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackstone, S.R. Evaluating antenatal care in Liberia: Evidence from the demographic and health survey. Women Health 2019, 59, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolde, H.F.; Tsegaye, A.T.; Sisay, M.M. Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Zemen primary hospital, South Gondar, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.-A.; Budu, E.; Mohammed, A.; Adu, C.; Agbaglo, E.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Yaya, S. Factors associated with the number and timing of antenatal care visits among married women in Cameroon: Evidence from the 2018 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2022, 54, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adulo, L.A.; Hassen, S.S. Magnitude and Factors Associated with Late Initiation of Antenatal Care Booking on First Visit Among Women in Rural Parts of Ethiopia. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 10, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigatu, S.G.; Birhan, T.Y. The magnitude and determinants of delayed initiation of antenatal care among pregnant women in Gambia; evidence from Gambia demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotoh, A.M.; Boah, M. “No visible signs of pregnancy, no sickness, no antenatal care”: Initiation of antenatal care in a rural district in Northern Ghana. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rurangirwa, A.A.; Mogren, I.; Nyirazinyoye, L.; Ntaganira, J.; Krantz, G. Determinants of poor utilization of antenatal care services among recently delivered women in Rwanda; a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towongo, M.F.; Ngome, E.; Navaneetham, K.; Letamo, G. Factors associated with Women’s timing of first antenatal care visit during their last pregnancy: Evidence from 2016 Uganda demographic health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragaw, F.M.; Alem, A.Z.; Asratie, M.H.; Chilot, D.; Belay, D.G. Spatial distribution of delayed initiation of antenatal care visits and associated factors among reproductive age women in Ethiopia: Spatial and multilevel analysis of 2019 mini-demographic and health survey. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda-Taylor, L.; Sealy, D.; Roberts, J. Factors associated with delayed antenatal care attendance in Malawi: Results from a qualitative study. Med. J. Zamb. 2017, 44, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letsie, T.M.; Lenka, M. Factors Contributing to the Late Commencement of Antenatal Care at a Rural District Hospital in Lesotho. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2021, 13, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warri, D.; George, A. Perceptions of pregnant women of reasons for late initiation of antenatal care: A qualitative interview study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, R.; Mohammadnezhad, M. Perception of pregnant women towards early antenatal visit in Fiji: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassey, B. Determinants of Early Antenatal Care Visits Attending Antenatal Care in Rural Gambia. J. Medicoeticolegal Dan Manaj. Rumah Sakit 2023, 12, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Mishra, P.S. Inequality in time to first antenatal care visits and its predictors among pregnant women in India: An evidence from national family health survey. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfiq, E.; Fazli, M.R.; Wasiq, A.W.; Stanikzai, M.H.; Mansouri, A.; Saeedzai, S.A. Sociodemographic Predictors of Initiating Antenatal Care Visits by Pregnant Women during First Trimester of Pregnancy: Findings from the Afghanistan Health Survey 2018. Int. J. Women’s Health 2023, 15, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadoulougou, S.; Sawadogo, K.; Robert, A. Regional disparities of late entry to antenatal care and associated sociodemographic barriers in Burkina Faso. Rev. D’épidémiologie Santé Publique 2018, 66, S435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A.A.; Dahiru, T. Predictors of delayed Antenatal Care (ANC) visits in Nigeria: Secondary analysis of 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS). Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017, 26, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyuma, E.S.; Cummings-Wray, D.; Sao Babawo, L. Factors associated with late antenatal care initiationfor pregnant women aged 15–49 years in Sierra Leone using the 2019 Demographic Health Survey. Midwifery 2022, 6, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mulungi, A.; Mukamurigo, J.; Rwunganira, S.; Njunwa, K.; Ntaganira, J. Prevalence and risk factors for delayed antenatal care visits in Rwanda: An analysis of secondary data from Rwanda demographic health survey 2019–2020. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2023, 44, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, K.; Mengistie, B.; Gobena, T.; Dheresa, M.; Seme, A. Adequacy and timeliness of antenatal care visits among Ethiopian women: A community-based panel study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, K.; Chomienne, M.-H.; Geneau, R.; Yaya, S. Socio-economic and cultural factors associated with the utilization of maternal healthcare services in Togo: A cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, A.M.; Bitew, B.D.; Koye, D.N. Prevalence and determinants of early antenatal care visit among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Debre Berhan Health Institutions, Central Ethiopia. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2013, 17, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amungulu, M.E.; Nghitanwa, E.M.; Mbapaha, C. An investigation of factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care services among women in post-natal wards in two Namibian hospitals in the Khomas region. J. Public Health Afr. 2023, 14, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njiku, F.; Wella, H.; Sariah, A.; Protas, J. Prevalence and factors associated with late antenatal care visit among pregnant women in Lushoto, Tanzania. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 2017, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadufashije, D.; Sangano, G.B.; Samuel, R. Barriers to antenatal care services seeking in Africa. SSRN 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drigo, L.; Luvhengo, M.; Lebese, R.T.; Makhado, L. Attitudes of pregnant women towards antenatal care services provided in primary health care facilities of Mbombela municipality, Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Open Public Health J. 2020, 13, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuire, V.Z.; Kangmennaang, J.; Atuoye, K.N.; Antabe, R.; Boamah, S.A.; Vercillo, S.; Amoyaw, J.A.; Luginaah, I. Timing and utilisation of antenatal care service in Nigeria and Malawi. Glob. Public Health 2017, 12, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebonwu, J.; Mumbauer, A.; Uys, M.; Wainberg, M.L.; Medina-Marino, A. Determinants of late antenatal care presentation in rural and peri-urban communities in South Africa: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| % | N | First ANC Visit | X2 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Late | |||||

| Age (years) | 11.80 | 0.066 | ||||

| 15–19 | 8.6 | 1134 | 21.3 | 78.7 | ||

| 20–24 | 28.9 | 3824 | 24.8 | 75.2 | ||

| 25–29 | 23.7 | 3143 | 24.8 | 75.2 | ||

| 30–34 | 19.7 | 2606 | 25.9 | 74.1 | ||

| 35–39 | 12.1 | 1600 | 23.9 | 76.1 | ||

| 40–44 | 5.2 | 683 | 22.5 | 77.5 | ||

| 45–49 | 2.0 | 262 | 22.1 | 77.9 | ||

| Region | 3.29 | 0.193 | ||||

| Northern Region | 11.8 | 1565 | 24.3 | 75.7 | ||

| Central Region | 42.6 | 5642 | 23.7 | 76.3 | ||

| Southern Region | 45.6 | 6043 | 25.2 | 74.8 | ||

| Place of residence | 2.05 | 0.153 | ||||

| Urban | 14.5 | 1919 | 25.7 | 74.3 | ||

| Rural | 85.5 | 11,331 | 24.2 | 75.8 | ||

| Education | 62.01 | 0.000 | ||||

| No education | 12.4 | 1637 | 21.9 | 78.1 | ||

| Primary | 65.4 | 8669 | 24.2 | 75.8 | ||

| Secondary | 20.2 | 2682 | 24.8 | 75.2 | ||

| Higher | 2.0 | 262 | 44.3 | 55.7 | ||

| Frequency of reading newspaper | 4.64 | 0.098 | ||||

| Not at all | 82.4 | 10,922 | 24.1 | 75.9 | ||

| Less than once a week | 10.9 | 1438 | 25.5 | 74.5 | ||

| At least once a week | 6.7 | 890 | 27.0 | 73.0 | ||

| Frequency of listening to radio | 8.13 | 0.017 | ||||

| Not at all | 52.3 | 6930 | 23.7 | 76.3 | ||

| Less than once a week | 18.3 | 2430 | 24.1 | 75.9 | ||

| At least once a week | 29.4 | 3891 | 26.1 | 73.9 | ||

| Frequency of watching TV | 17.97 | 0.000 | ||||

| Not at all | 83.8 | 11,098 | 23.9 | 76.1 | ||

| Less than once a week | 7.4 | 977 | 25.1 | 74.9 | ||

| At least once a week | 8.9 | 1176 | 29.4 | 70.6 | ||

| Sex of head of household | ||||||

| Male | 74.8 | 9907 | 24.9 | 75.1 | 4.14 | 0.042 |

| Female | 25.2 | 3344 | 23.1 | 76.9 | ||

| Marital status | 17.89 | 0.000 | ||||

| Never married | 3.8 | 510 | 16.9 | 83.1 | ||

| Married | 82.9 | 10,986 | 24.9 | 75.1 | ||

| Formerly married | 13.2 | 1755 | 23.6 | 76.4 | ||

| Work status | 0.14 | 0.708 | ||||

| No | 33.7 | 4461 | 24.3 | 75.7 | ||

| Yes | 66.3 | 8790 | 24.6 | 75.4 | ||

| Knowledge of family planning | 0.44 | 0.509 | ||||

| No | 0.2 | 31 | 19.4 | 80.6 | ||

| Yes | 99.8 | 13,220 | 24.5 | 75.5 | ||

| Ever use family planning | 5.80 | 0.016 | ||||

| No | 13.7 | 1820 | 22.2 | 77.8 | ||

| Yes | 86.3 | 11,431 | 24.8 | 75.2 | ||

| Visits | 1130.64 | 0.000 | ||||

| <4 | 48.4 | 6418 | 11.5 | 88.5 | ||

| ≥4 | 51.6 | 6832 | 36.6 | 63.4 | ||

| Wealth | 24.40 | 0.000 | ||||

| Poorest | 23.3 | 3094 | 22.2 | 77.8 | ||

| Poorer | 21.7 | 2879 | 24.5 | 75.5 | ||

| Middle | 19.1 | 2532 | 23.1 | 76.9 | ||

| Richer | 18.1 | 2402 | 26.0 | 74.0 | ||

| Richest | 17.7 | 2344 | 27.3 | 72.7 | ||

| Last child by caesarean section | 41.95 | 0.000 | ||||

| No | 93.5 | 12,353 | 23.8 | 76.2 | ||

| Yes | 6.5 | 852 | 33.7 | 66.3 | ||

| Parity | 5.95 | 0.051 | ||||

| 1–2 | 44.8 | 5942 | 25.4 | 74.6 | ||

| 3–4 | 30.1 | 3987 | 23.4 | 76.6 | ||

| 5+ | 25.1 | 3322 | 24.0 | 76.0 | ||

| Wanted last child | ||||||

| Wanted then | 56.9 | 7541 | 26.4 | 73.6 | 39.50 | 0.000 |

| Wanted later | 31.1 | 4117 | 21.3 | 78.7 | ||

| Wanted no more | 12.0 | 1594 | 23.4 | 76.6 | ||

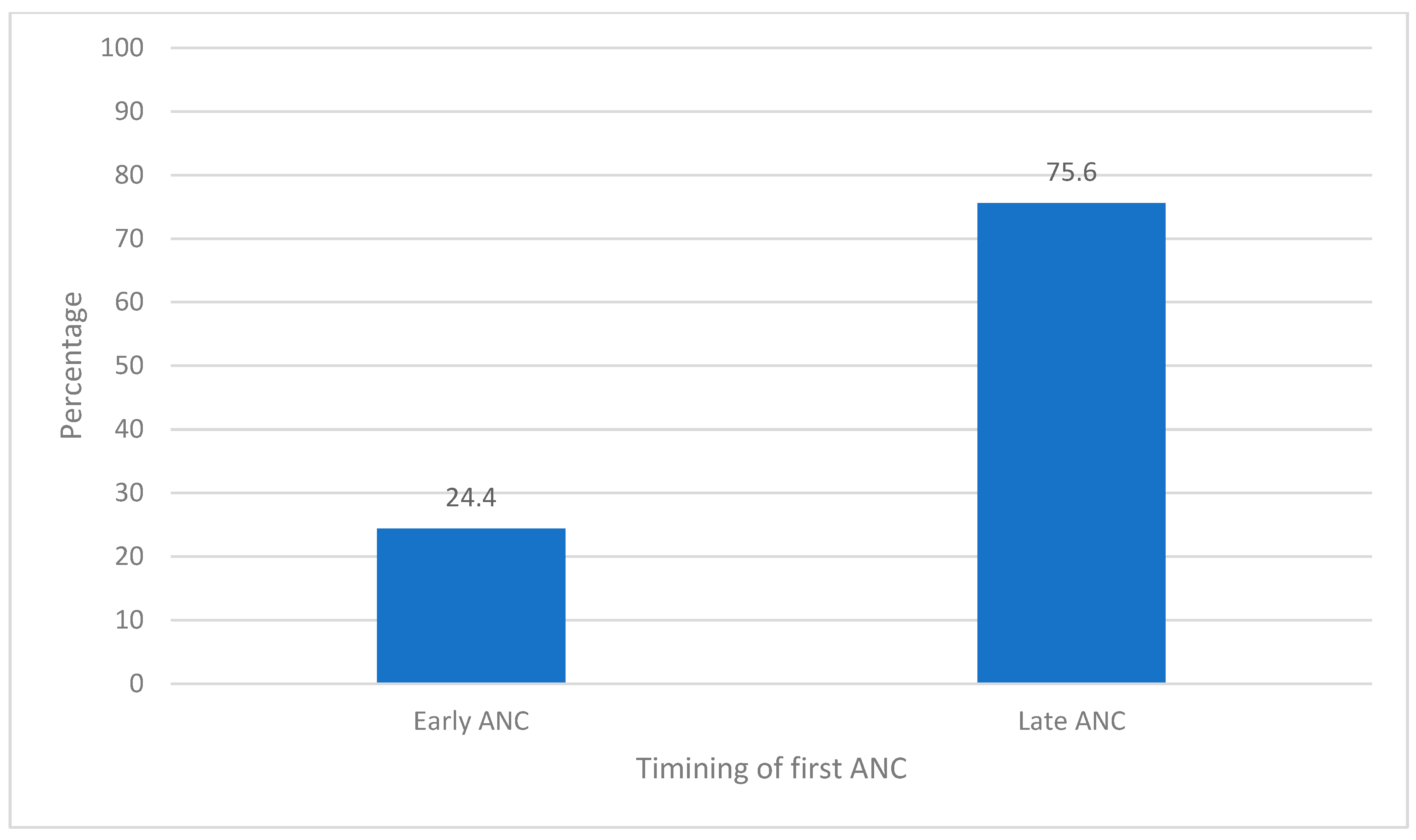

| 100.0 | 13,252 | 24.4 | 75.6 | |||

| Age (years) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 | 0.701 | 0.487 | 1.009 |

| 20–24 | 0.634 ** | 0.456 | 0.881 |

| 25–29 | 0.645 ** | 0.476 | 0.874 |

| 30–34 | 0.636 ** | 0.479 | 0.845 |

| 35–39 | 0.707 * | 0.534 | 0.935 |

| 40–44 | 0.778 | 0.571 | 1.062 |

| 45–49 (Reference) | |||

| Region | |||

| Northern Region | 1.158 * | 1.009 | 1.329 |

| Central Region | 1.165 ** | 1.063 | 1.276 |

| Southern Region (Reference) | |||

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban | 1.203 * | 1.036 | 1.396 |

| Rural (Reference) | |||

| Education | |||

| No education | 1.814 *** | 1.354 | 2.429 |

| Primary | 1.697 *** | 1.301 | 2.214 |

| Secondary | 1.793 *** | 1.390 | 2.312 |

| Higher (Reference) | |||

| Frequency of reading newspaper | |||

| Not at all | 0.987 | 0.832 | 1.172 |

| Less than once a week | 1.003 | 0.820 | 1.225 |

| At least once a week (Reference) | |||

| Frequency of listening to radio | |||

| Not at all | 1.023 | 0.922 | 1.136 |

| Less than once a week | 1.049 | 0.925 | 1.190 |

| At least once a week (Reference) | |||

| Frequency of watching TV | |||

| Not at all | 1.029 | 0.864 | 1.226 |

| Less than once a week | 1.050 | 0.850 | 1.296 |

| At least once a week (Reference) | |||

| Sex of head of household | |||

| Male | 0.923 | 0.821 | 1.039 |

| Female (Reference) | |||

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 1.436 * | 1.082 | 1.904 |

| Married | 1.001 | 0.865 | 1.157 |

| Formerly married (Reference) | |||

| Work status | |||

| No | 0.940 | 0.857 | 1.030 |

| Yes (Reference) | |||

| Visits | |||

| <4 | 4.382 *** | 3.995 | 4.806 |

| ≥4 (Reference) | |||

| Wealth | |||

| Poorest | 1.117 | 0.929 | 1.342 |

| Poorer | 0.997 | 0.835 | 1.191 |

| Middle | 1.082 | 0.906 | 1.291 |

| Richer | 0.919 | 0.778 | 1.086 |

| Richest (Reference) | |||

| Last child by caesarean section | |||

| No | 1.377 *** | 1.179 | 1.607 |

| Yes (Reference) | |||

| Parity | |||

| 1–2 | 0.962 | 0.803 | 1.152 |

| 3–4 | 1.089 | 0.946 | 1.254 |

| 5+ (Reference) | |||

| Wanted last child | |||

| Wanted then | 0.971 | 0.839 | 1.123 |

| Wanted later | 1.156 | 0.988 | 1.352 |

| Wanted no more (Reference) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palamuleni, M.E. Factors Associated with Late Antenatal Initiation among Women in Malawi. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020143

Palamuleni ME. Factors Associated with Late Antenatal Initiation among Women in Malawi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(2):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020143

Chicago/Turabian StylePalamuleni, Martin Enock. 2024. "Factors Associated with Late Antenatal Initiation among Women in Malawi" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 2: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020143