Improving Accessibility to Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): Barriers to Early Diagnosis and Timely Treatment in Latin America

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Health System in Latin America—A Brief Description of the Health Systems in Brazil and Mexico

2.1. Brazilian Health System

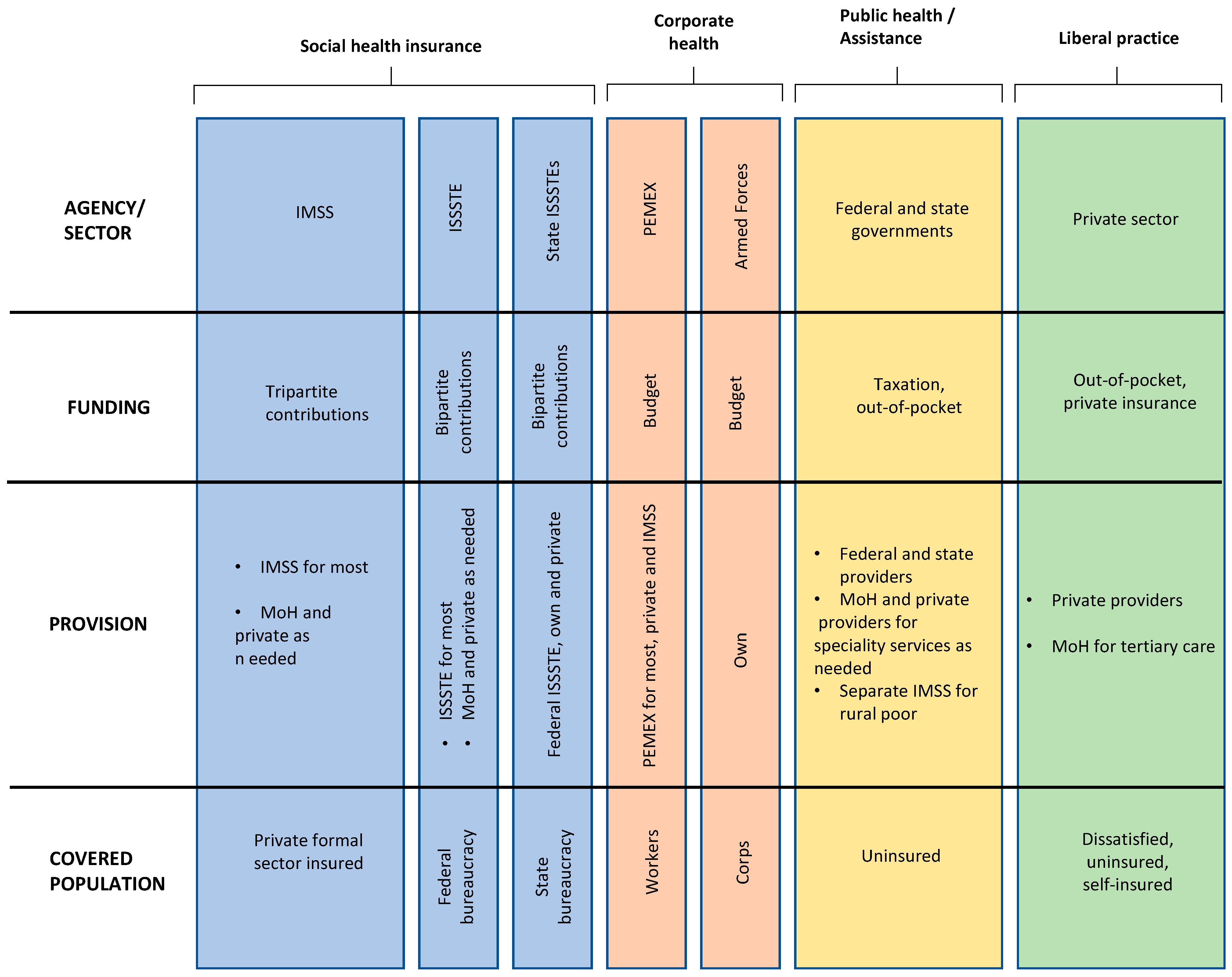

2.2. Mexican Health System

3. Methods

3.1. Panel Study Methodology

3.2. Data Acquisition

4. Results

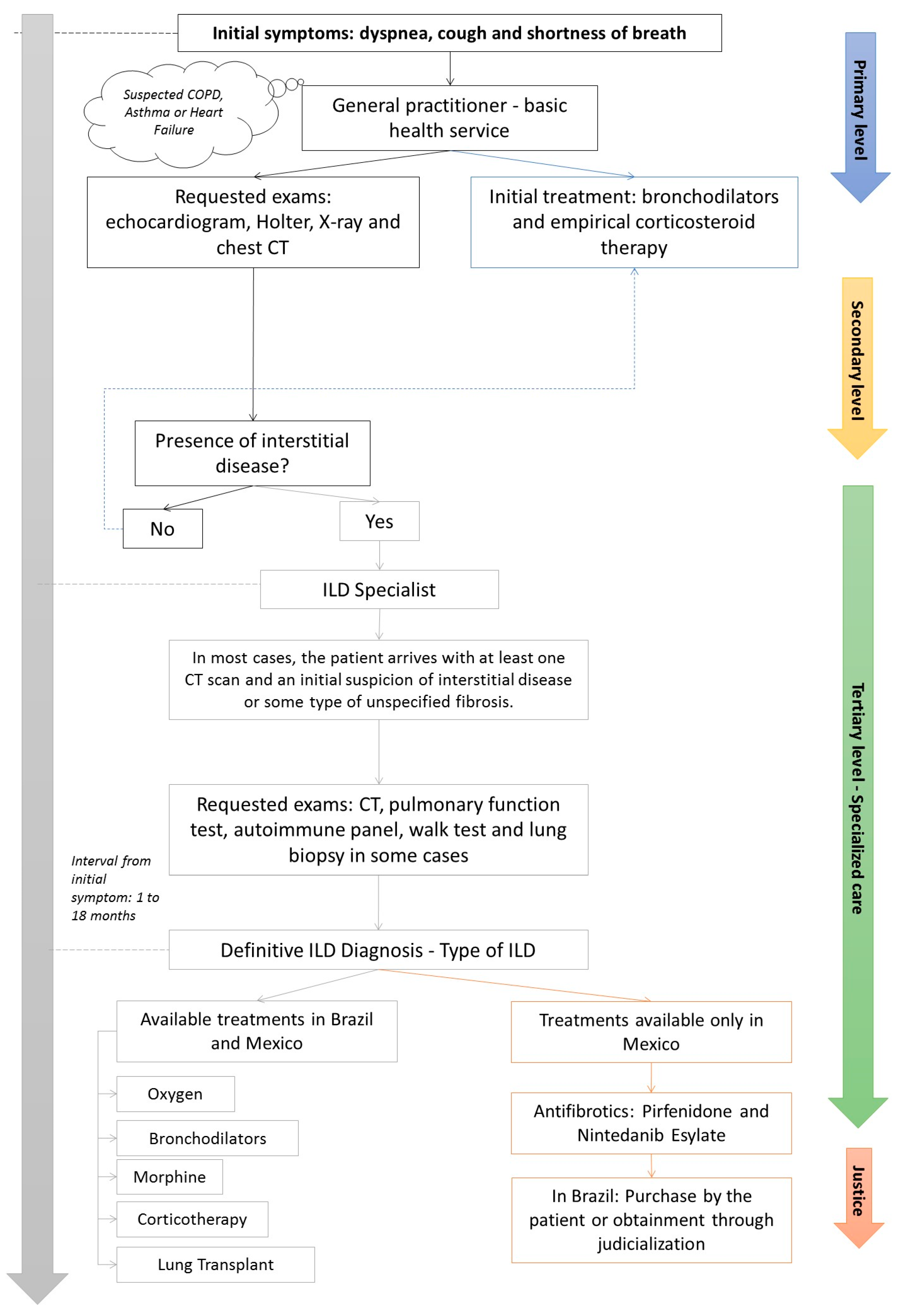

4.1. Patient’s Journey

4.2. Antifibrotic Therapy for ILD

4.3. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on ILD Patients’ Journey

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mikolasch, T.A.; Garthwaite, H.S.; Porter, J.C. Update in diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Clin. Med. 2017, 17, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia. Diretrizes de Doenças Pulmonares Intersticiais da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2012, 38 (Suppl. S2), S1–S133. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.; Slutsky, A.S. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis—New Insights. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1370–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harari, S.; Caminati, A. IPF: New insight on pathogenesis and treatment. Allergy 2010, 65, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller-Mang, C.; Ringl, H.; Herold, C. Interstitial Lung Diseases. In Multislice CT; Nikolaou, K., Bamberg, F., Laghi, A., Rubin, G.D., Eds.; Medical Radiology; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, T.M. Interstitial Lung Disease: A Review. JAMA, 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Ryerson, C.J.; Putman, R.; Oldham, J.; Salisbury, M.; Sverzellati, N.; Valenzuela, C.; Guler, S.; Jones, S.; Wijsenbeek, M.; et al. Early diagnosis of fibrotic interstitial lung disease: Challenges and opportunities. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, D.J.; Martinez, F.J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, T.M.; Bendstrup, E.; Dron, L.; Langley, J.; Smith, G.; Khalid, J.M.; Patel, H.; Kreuter, M. Global incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddini-Martinez, J.; Ferreira, J.; Tanni, S.; Alves, L.R.; Cabral Junior, B.F.; Carvalho, C.R.R.; Cezare, T.J.; Costa, C.H.D.; Gazzana, M.B.; Jezler, S.; et al. Brazilian guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Official document of the Brazilian Thoracic Association based on the GRADE methodology. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2020, 46, e20190423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.J.; Safrin, S.; Weycker, D.; Starko, K.M.; Bradford, W.Z.; King, T.E., Jr.; Flaherty, K.R.; Schwartz, D.A.; Noble, P.W.; Raghu, G.; et al. The Clinical Course of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. AJRCCM 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, R.; Liakouli, V.; Berardicurti, O.; Ruscitti, P.; Di Benedetto, P.; Carubbi, F.; Guggino, G.; Di Bartolomeo, S.; Ciccia, F.; Triolo, G.; et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: Current and future treatment. Rheumatol. Int. 2017, 37, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, G.; Bocchino, M. The challenge of diagnosing interstitial lung disease by HRCT: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2021, 47, e20210199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elicker, B.; Pereira, C.A.D.C.; Webb, R.; Leslie, K.O. Padrões tomográficos das doenças intersticiais pulmonares difusas com correlação clínica e patológica. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2008, 34, 715–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, K.R.; Andrei, A.C.; King, T.E., Jr.; Raghu, G.; Colby, T.V.; Wells, A.; Bassily, N.; Brown, K.; Du Bois, R.; Flint, A.; et al. Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia: Do Community and Academic Physicians Agree on Diagnosis? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Lung Foundation. Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD). Available online: https://europeanlung.org/en/information-hub/lung-conditions/interstitial-lung-disease/ (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Brown, K.K.; Martinez, F.J.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Thannickal, V.J.; Prasse, A.; Schlenker-Herceg, R.; Goeldner, R.-G.; Clerisme-Beaty, E.; Tetzlaff, K.; Cottin, V.; et al. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2000085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, K.R.; Wells, A.U.; Cottin, V.; Devaraj, A.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Inoue, Y.; Richeldi, L.; Kolb, M.; Tetzlaff, K.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Nintedanib in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, Y.N. Nintedanib: A Review in Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases. Drugs 2021, 81, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constituição. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil; Senado (DF): Brasília, Brazil, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Paim, J.S.; Travassos, C.M.D.R.; Almeida, C.M.D.; Bahia, L.; Macinko, J. O sistema de saúde brasileiro: História, avanços e desafios. Lancet 2011, 377, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Block, M.A.; Morales, H.R.; Hurtado, L.C.; Balandrán, A.; Méndez, E. Health Systems in Transition. In Mexico Health System Review; North American Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 22, No. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fiocruz. PublicoxPrivado. Available online: https://pensesus.fiocruz.br/publico-x-privado (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Minas Gerais—Secretaria de Estado de Saúde. Available online: https://www.saude.mg.gov.br/sus (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Campos, R.T.O.; Miranda, L.; Gama, C.A.P.; Ferrer, A.L.; Diaz, A.R.; Gonçalves, L.; Trapé, T.L. Oficinas de construção de indicadores e dispositivos de avaliação: Uma nova técnica de consenso. Estud. Pesqui. Psicol. 2010, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coube, M.; Nikoloski, Z.; Mrejen, M.; Mossialos, E. Inequalities in unmet need for health care services and medications in Brazil: A decomposition analysis. Lancet Reg. Health—Am. 2023, 19. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(22)00243-5/fulltext (accessed on 5 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) (Brasil). Consultas. Available online: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/medicamentos/25351456304201563/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no SUS (CONITEC) (Brasil). Available online: http://conitec.gov.br/tecnologias-em-avaliacao-demandas-por-status (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Mexico—Secretaria de Salud Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/196773/Huerfanos_Otorgados_2015.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Mexico. Proposición con punto de acuerdo por el que la comisiòn permanente del h. congreso de la unión con pleno respeto a la división de poderes, exhorta a la secretaría de salud para que, en coordinación con las autoridades competentes analice definir a la fibrosis pulmonar idiopática (fpi) como una enfermedad catastrófica y fortalezca las acciones y estrategias para su prevención, detección y, en su caso, brindar el tratamiento oportuno en dicho padecimiento. Ciudad de México a, 24 de julio de 2018.

- Expert Panel: Rubin Adalberto MD, Gassman Ricardo MD, Díaz-Verduzco Manuel de Jesús MD, and Alemán-Márquez Ángel MD, from the Expert Panel of Reference Centers in Interstitial Lung Diseases in Latin America. June 2021.

- Litewka, S.G.; Heitman, E. Latin American healthcare systems in times of pandemic. Dev. World Bioeth. 2020, 20, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vasarmidi, E.; Ghanem, M.; Crestani, B. Interstitial lung disease following coronavirus disease 2019. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2022, 28, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, D.K.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, R. Post COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis. Is it real threat? Indian J. Tuberc. 2021, 68, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Tan, W.; Yuan, M.; Ding, X.; Zou, J.; et al. Risk factors associated with disease severity and length of hospital stay in COVID-19 patients. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e95–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guler, S.A.; Ebner, L.; Aubry-Beigelman, C.; Bridevaux, P.O.; Brutsche, M.; Clarenbach, C.; Garzoni, C.; Geiser, T.K.; Lenoir, A.; Mancinetti, M.; et al. Pulmonary function and radiological features 4 months after COVID-19: First results from the national prospective observational Swiss COVID-19 lung study. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2003690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, G.P.; Bianchi, P.; Danese, S.; Lederer, D.J. Barriers to timely diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in the real world: The INTENSITY survey. BMC Pulm. Med. 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.H.; Beegle, S.; Hotchkin, D.L.; Kaelin, T.; Kim, H.J.; Podolanczuk, A.J.; Ramaswamy, M.; Remolina, C.; Salvatore, M.M.; Tu, C.; et al. Defining the pathway to timely diagnosis and treatment of interstitial lung disease: A US Delphi survey. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moor, C.C.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Balestro, E.; Biondini, D.; Bondue, B.; Cottin, V.; Flewett, R.; Galvin, L.; Jones, S.; Molina-Molina, M.; et al. Gaps in care of patients living with pulmonary fibrosis: A joint patient and expert statement on the results of a Europe-wide survey. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00124–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dempsey, T.M.; Sangaralingham, L.R.; Yao, X.; Sanghavi, D.; Shah, N.D.; Limper, A.H. Clinical Effectiveness of Antifibrotic Medications for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašáková, M.; Mogulkoc, N.; Šterclová, M.; Zolnowska, B.; Bartoš, V.; Plačková, M.; Müller, V.; Lacina, L.; Slivka, R.; Doubková, M.; et al. Does timeliness of diagnosis influence survival and treatment response in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Real-world results from the EMPIRE registry. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50 (Suppl. S61), PA4880. [Google Scholar]

| General Hospital | Philanthropic Hospital | ISSSTE Hospital | Navy Hospital | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic location | Feira de Santana, Northeast Brazil | Porto Alegre, South Brazil | Culiacán, Northwest Mexico | Veracruz, Southeast Mexico |

| ILD patients managed in a typical year | 200 | 200 | 150 | 120 |

| Elapsed time for referral in days | 180–540 | 180–540 | 30–360 | 15–360 |

| Guidelines or protocols followed by this institution | ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT and SBPT guidelines | ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT and SBPT guidelines | ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT guideline | ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT guideline |

| Multidisciplinary team for ILD patients at this institution | Pulmonologist, rheumatologist, thoracic radiologist, thoracic surgeon | Pulmonologist, rheumatologist, thoracic radiologist, lung pathologist, thoracic surgeon | Pulmonologist, rheumatologist, thoracic surgeon | Pulmonologist, rheumatologist, thoracic surgeon |

| Diagnostic workup | Spirometry, lung volumes, DLCO, 6MWT, chest X-ray, HRCT, serologic workup to detect autoimmune diseases, surgical lung biopsy, bronchoscopy | Spirometry, lung volumes, DLCO, 6MWT, HRCT, serologic workup to detect autoimmune diseases, surgical lung biopsy, bronchoscopy | Spirometry, lung volumes, DLCO, 6MWT, HRCT, serologic workup to detect autoimmune diseases, surgical lung biopsy, bronchoscopy | Spirometry, 6MWT, HRCT, serologic workup to detect autoimmune diseases, surgical lung biopsy, bronchoscopy |

| Treatments for ILD available on this institution | Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, biologics, antifibrotic, oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation | Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, biologics, antifibrotic, oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation, lung transplant | Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, biologics, antifibrotic, oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation | Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, biologics, antifibrotic, oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation |

| Average time in days (minimum, maximum) for commencing antifibrotics | 120 (30, 240) | 120 (60, 180) | 15 (1, 60) | 20 (7, 30) |

| Brazilian Health System | Mexican Health System | |

|---|---|---|

| Organization | Public healthcare services | Public healthcare services |

| Private supplementary healthcare services | Social security institutions | |

| Private supplementary healthcare services | ||

| Coverage | Universal Coverage, with comprehensive services available to all citizens | IMSS and ISSSTE provide coverage primarily to formal sector workers and government employees, this leaves a significant portion of the population with a limited access to healthcare services |

| Service delivery | Brazil emphasizes community-based care through the Family Health Program (Programa Saude da Família), focusing on preventive and primary care. This approach helps to improve health outcomes, especially in remote and underserved areas | Mexico relies on a hospital-centric system, which could lead to overburdened facilities and challenges in providing accessible primary care services |

| Funding mechanisms | A decentralized administration. SUS is managed at the municipal, state, and federal levels, allowing for localized decision-making | Mexico maintains a more centralized governance structure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Figueiredo, R.G.; Duarte, N.F.V.; Campos, D.C.B.; de Jesus Diaz Verduzco, M.; Márquez, Á.A.; de Araujo, G.T.B.; Rubin, A.S. Improving Accessibility to Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): Barriers to Early Diagnosis and Timely Treatment in Latin America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050647

Figueiredo RG, Duarte NFV, Campos DCB, de Jesus Diaz Verduzco M, Márquez ÁA, de Araujo GTB, Rubin AS. Improving Accessibility to Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): Barriers to Early Diagnosis and Timely Treatment in Latin America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(5):647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050647

Chicago/Turabian StyleFigueiredo, Ricardo G., Nathalia Filgueiras Vilaça Duarte, Daniela Carla Barbosa Campos, Manuel de Jesus Diaz Verduzco, Ángel Alemán Márquez, Gabriela Tannus Branco de Araujo, and Adalberto Sperb Rubin. 2024. "Improving Accessibility to Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): Barriers to Early Diagnosis and Timely Treatment in Latin America" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 5: 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050647

APA StyleFigueiredo, R. G., Duarte, N. F. V., Campos, D. C. B., de Jesus Diaz Verduzco, M., Márquez, Á. A., de Araujo, G. T. B., & Rubin, A. S. (2024). Improving Accessibility to Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD): Barriers to Early Diagnosis and Timely Treatment in Latin America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(5), 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21050647