Suicide Risk Factors in High School Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study

2.2. Participants

2.3. Context

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

- Assess suicidal orientation in adolescents enrolled in the SEMS using the Inventory of Suicide Orientation-30 (ISO-30).

- Post-stratify the sample with a secondary analysis that focused on students with a higher global risk index (raw score of 45 or greater or critical item score of 3 or greater); suicide risk was determined using an online survey that provided evaluation in 6 behavioral areas.

2.5. Measurements

2.5.1. Suicidal Orientation and Ideation

2.5.2. Family Functioning

2.5.3. Depressive Symptoms

2.5.4. Health-Related Quality of Life

2.5.5. Experience of Bullying

2.5.6. Impulsivity

2.5.7. Substance Use and Abuse

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

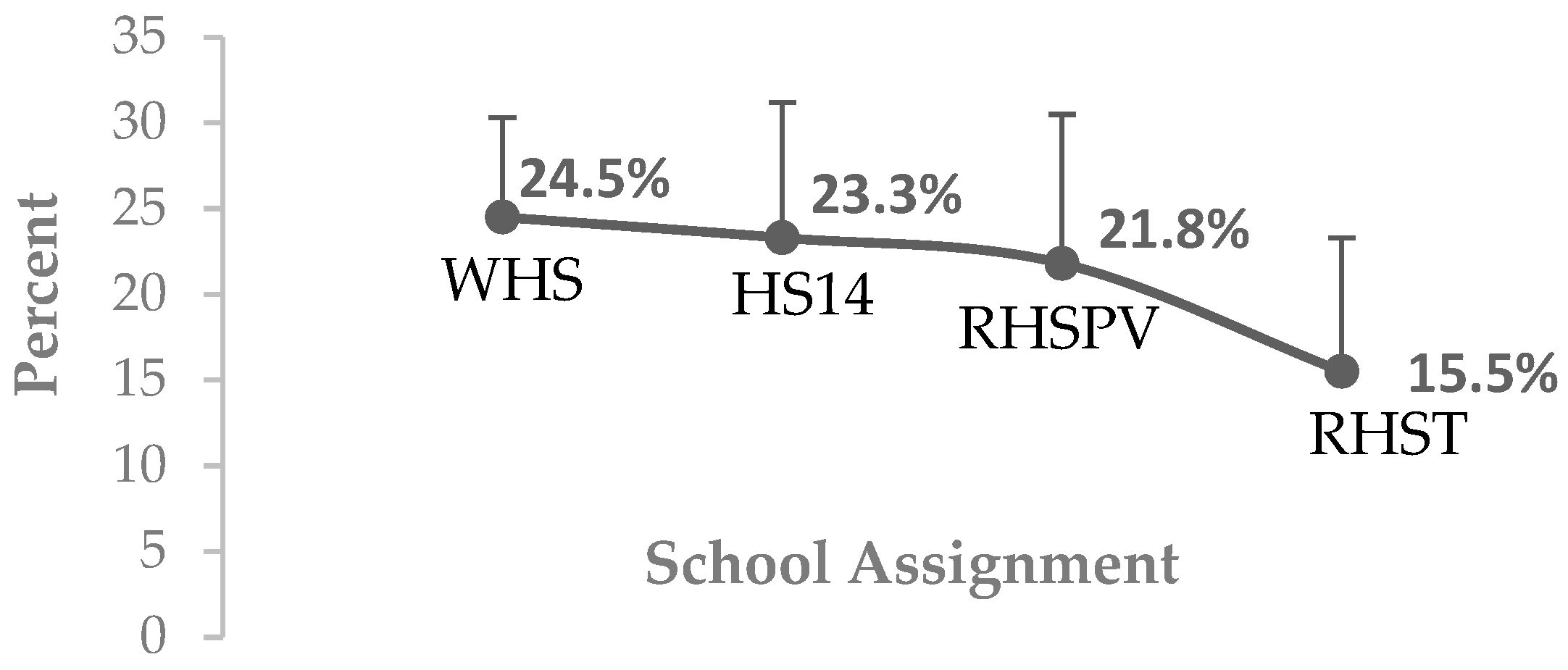

3.1. Suicide Risk Assessment in SEMS Students (Wixárika High School, High School No. 14, Regional High School of Puerto Vallarta, and Regional High School of Tepatitlán)

3.2. Characterization of Suicide Risk in SEMS Students (Wixárika High School, High School No. 14, Regional High School of Puerto Vallarta, and Regional High School of Tepatitlán)

3.2.1. Suicide Ideation

3.2.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan American Health Organization. Suicide Prevention. In Virtual Campus for Public Health; Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Delgado, G.; Almaraz-Vega, E.; Ramírez-Mireles, J.E.; Gutiérrez-Paredes, M.E.; Padilla-Galindo, M.D.R. Health-Related Quality of Life and Depressive Symptomatology in High School Students during the Lockdown Period Due to SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiorani, C.; Fernandez, I.; Tummino, V.; Verdi, D.; Gallina, E.; Pagani, M. Adolescence and COVID-19: Traumatic Stress and Social Distancing in the Italian Epicenter of Pandemic. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, M.G.; Palladini, M.; Poletti, S.; Benedetti, F. Post-COVID-19 Depressive Symptoms: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Pharmacological Treatment. CNS Drugs 2022, 36, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meherali, S.; Punjani, N.; Louie-Poon, S.; Rahim, K.A.; Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S. Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID-19 and past pandemics: A rapid systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostev, K.; Smith, L.; Koyanagi, A.; Konrad, M.; Jacob, L. Post-COVID-19 conditions in children and adolescents diagnosed with COVID-19. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 95, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmaz, A.; Karataş, H.; Ercan, T.M.F.; Erat, T.; Solmaz, F.; Kandemir, H. Anxiety in Paediatric Patients Diagnosed with COVID-19 and the Affecting Factors. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2022, 68, fmac018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Ye, M.; Fu, Y.; Yang, M.; Luo, F.; Yuan, J.; Quian, T. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teenagers in China. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.E.; Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Reiner, I.; Jünger, C.; Michal, M.; Wiltink, J.; Wild, P.S.; Münzel, T.; Lackner, K.L.; et al. Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.E.; Dumas, T.M.; Forbes, L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 52, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Sun, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Bu, T.; Chu, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; et al. Factors Influencing Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms in Chinese Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 892014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Zhao, L.; Dou, D.; Zhu, X.; Xiao, C. The Impact of Positive Youth Development Attributes on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Among Chinese Adolescents Under COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, J.; Seto, S.; Fukuda, Y.; Funakoshi, S.; Amae, S.; Onobe, J.; Izumi, S.; Ito, K.; Imamura, F. Mental health and physical activity among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2021, 253, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, L.; Behme, N.; Breuer, C. Physical activity of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic—A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.C.E.; Anedda, B.; Burchartz, A.; Eichsteller, A.; Kolb, S.; Nigg, C.; Niessner, C.; Oriwol, D.; Worth, A.; Woll, A. Physical activity and screen time of children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany: A natural experiment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bülow, A.; Keijsers, L.; Boele, S.; van Roekel, E.; Denissen, J.J.A. Parenting Adolescents in Times of a Pandemic: Changes in Relationship Quality, Autonomy Support, and Parental Control? Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1582–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinberg, M.E.; Mogle, J.A.; Lee, J.K.; Tornello, S.L.; Hostetler, M.L.; Cifelli, J.A.; Bai, S.; Hotez, E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Parent, Child, and Family Functioning. Fam. Process 2022, 61, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Storey, A.; Dirks, M.; Holfeld, B.; Dryburgh, N.S.J.; Craig, W. Family relationship quality during the COVID-19 pandemic: The value of adolescent perceptions of change. J. Adolesc. 2021, 93, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Ander, B.; Gurdal, S.; Sorbring, E. Adolescent smoking, alcohol use, inebriation, and use of narcotics during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, H.M.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Halldorsdottir, T.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Allegrante, J.P.; Kristjansson, A.L. Substance Use Among Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2022, 24, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Su, H.; Liao, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Pei, Y.; Jin, P.; Xu, J.; Qi, C. Gender Differences in Mental Health Disorder and Substance Abuse of Chinese International College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 710878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, S.A.; Kolahi, A.A.; Akhgari, M.; Gheshlaghi, F.; Gholami, N.; Moshiri, M.; Mohtasham, N.; Ebrahimi, S.; Ziaeefar, P.; McDonald, R.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic and methanol poisoning outbreak in Iranian children and adolescents: A data linkage study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 1853–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, K.; Liu, G.; Mallia, E.; Ow, N.; Glowacki, K.; Hastings, K.G.; Mathias, S.; Sutherland, J.M.; Barbic, S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol or drug use symptoms and service need among youth: A cross-sectional sample from British Columbia, Canada. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2022, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiton, M.; Dubray, J.; Kundu, A.; Schwartz, R. Perceived Impact of COVID on Smoking, Vaping, Alcohol and Cannabis Use Among Youth and Youth Adults in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2022, 67, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leatherdale, S.T.; Bélanger, R.E.; Gansaonré, R.J.; Patte, K.A.; deGroh, M.; Jiang, Y.; Haddad, S. Examining the impact of the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic period on youth cannabis use: Adjusted annual changes between the pre-COVID and initial COVID-lockdown waves of the COMPASS study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N.D.; Bohm, M.K.; Jones, C.M.; Puvanesarajah, S.; Robin, L.; Suarez, N.; Deng, X.; Harding, R.L.; Moyse, D. Supplement Use of Tobacco Products, Alcohol, and Other Substances Among High School Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic-Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2022, 71, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelham, W.E.; Tapert, S.F.; Gonzalez, M.R.; McCabe, C.J.; Lisdahl, K.M.; Alzueta, E.; Baker, F.C.; Breslin, F.J.; Dick, A.S.; Dowling, G.; et al. Early Adolescent Substance Use Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Survey in the ABCD Study Cohort. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Agostiniani, R.; Barni, S.; Russo, R.; Scarpato, E.; Di Mauro, A.; Di Stefano, A.V.; Caruso, C.; Corsello, G.; et al. The Use of Social Media in Children and Adolescents: Scoping Review on the Potential Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Girelli, L.; Mancone, S.; Corrado, S.; Valente, G.; Cavicchiolo, E. Impulsivity and Depressive Brooding in Internet Addiction: A Study With a Sample of Italian Adolescents During COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 941313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp-Langley, B.; Hutt, A. Digital Addiction and Sleep. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.Y.; Sun, Y.; Meng, S.Q.; Bao, Y.P.; Cheng, J.L.; Chang, X.W.; Ran, M.S.; Sun, Y.K.; Kosten, T.; Strang, J.; et al. Internet Addiction Increases in the General Population During COVID-19: Evidence From China. Am. J. Addict. 2021, 30, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augusti, E.M.; Saetren, S.S.; Hafstad, G.S. Violence and abuse experiences and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in a population-based sample of Norwegian adolescents. Child. Abuse Negl. 2021, 118, 105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2020, 2, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, C.; Steinert, J.I. Prevalence and risk factors of violence against women and children during COVID-19, Germany. Bull. World Health Organ 2021, 99, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loiseau, M.; Cottenet, J.; Bechraoui-Quantin, S.; Gilard-Pioc, S.; Mikaeloff, Y.; Jollant, F.; François-Purssell, I.; Jud, A.; Quantin, C. Physical abuse of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Alarming increase in the relative frequency of hospitalizations during the lockdown period. Child. Abuse Negl. 2021, 122, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekaoui, N.; Aouragh, H.; Jeddi, Y.; Rhalem, H.; Dakhama, B.S.B.; Karboubi, L. Child sexual abuse and COVID-19 pandemic: Another side effect of lockdown in Morocco. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu-Addo, E.; Owusu-Addo, S.B.; Bennor, D.M.; Mensah-Odum, N.; Deliege, A.; Bansal, A.; Yoshikawa, M.; Odame, J. Prevalence and determinants of sexual abuse among adolescent girls during the COVID-19 lockdown and school closures in Ghana: A mixed method study. Child. Abuse Negl. 2023, 135, 105997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soron, T.R.; Ashiq, M.A.R.; Al-Hakeem, M.; Chowdhury, Z.F.; Ahmed, H.U.; Chowdhury, C.A. Domestic violence and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e24624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Y.J.; Barrero, V.I. The impact of school closure on children’s well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 67, 102957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. Mental health impact of online learning: A look into university students in Brunei Darussalam. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 67, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talavera-Salas, I.X.; Zela-Pacori, C.E.; Calcina-Cuevas, S.C.; Castillo-Machaca, J.E. Impacto de la COVID-19 en el estrés académico en estudiantes universitarios. Dominio Las Cienc. 2021, 7, 1673–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash-Abdo, H. Adolescent suicide: An ecological approach. Psychol. Sch. 2002, 39, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Amezcua, B.; Rivera-Rivera, L.; Atienzo, E.E.; de Castro, F.; Leyva-López, A.; Chávez-Ayala, R. Prevalencia y factores asociados a la ideación e intento suicida en adolescentes de educación media superior de la República mexicana [Prevalence and factors associated with suicidal behavior among Mexican students]. Salud Publica Mex. 2010, 52, 324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kweon, Y.S.; Hong, H.J. Suicidal Ideation, Depression, and Insomnia in Parent Survivors of Suicide: Based on Korean Psychological Autopsy of Adolescent Suicides. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivia, M.; Silva, D.; Sanhueza, F.; Cova, F.; Melipillán, R. Prevalencia de intento de suicidio adolescente y factores de riesgo asociados en una comuna rural de la provincia de Concepción. Rev. Med. Chil. 2015, 143, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, K.L.; Nakonezny, P.A.; Owen, V.J.; Rial, K.V.; Moorehead, A.P.; Kennard, B.D.; Emslie, G.J. Hopelessness as a Predictor of Suicide Ideation in Depressed Male and Female Adolescent Youth. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbi, G.; Atkin, T.; Zytynski, T.; Wang, S.; Askari, S.; Boruff, J.; Were, M.; Marmorstein, N.; Cipriani, A.; Dendukuri, N. Association of Cannabis Use in Adolescence and Risk of Depression, Anxiety, and Suicidality in Young Adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Torres, I.L.; Ahmad, M.; Martín-Álvarez, J.M.; Golpe, A.A.; Gil-Herrera, R.d.J. Mental health, suicide attempt, and family function for adolescents’ primary health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. F1000Research 2022, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Q.A.; Krauthamer, E.S.; Weiler, L.M.; Ogbaselase, F.A.; Mendenhall, T.; McGuire, J.K.; Monet, M.; Kobak, R.; Diamond, G.S. Family relationships and the interpersonal theory of suicide in a clinically suicidal sample of adolescents. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2022, 48, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, D.; Löfving, S.; Gustafsson, J.E.; Allebeck, P. School performance and risk of suicide in early adulthood: Follow-up of two national cohorts of Swedish schoolchildren. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 131, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Li, W.; Gong, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.H.; Lu, C. Association of emotional and behavioral problems with single and multiple suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: Modulated by academic performance. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 258, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörberg-Wallin, A.; Zeebari, Z.; Lager, A.; Gunnell, D.; Allebeck, P.; Falkstedt, D. Suicide attempt predicted by academic performance and childhood IQ: A cohort study of 26,000 children. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 137, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Boergers, J.; Spirito, A.; Little, T.D.; Grapentine, W.L. Peer Functioning, Family Dysfunction, and Psychological Symptoms in a Risk Factor Model for Adolescent Inpatients’ Suicidal Ideation Severity. J. Clin. Child. Psychol. 2000, 29, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.M.; Lowry, L.S.; Wuensch, K.L. Racial Differences in Adolescents’ Answering Questions About Suicide. Death Stud. 2015, 39, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Luaces, L.; Phillips, J.A. Racial and ethnic differences in risk factors associated with suicidal behavior among young adults in the USA. Ethn. Health 2014, 19, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Cerel, J.; Mann, J.J. Temporal Trends in Suicidal Ideation and Attempts Among US Adolescents by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 1991–2019. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2113513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Schuman, D.L. Suicide in the Time of COVID-19: A Perfect Storm. J. Rural. Health 2021, 37, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, L.; Peters, J.J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM 2020, 13, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, S.J.; Klepacz, L.; Lynch, S.; Shahar, S.; Dornbush, R.; Smiley, A.; Miller, I.; Tacakkoli, M.; Regan, J.; Bartell, A. Psychiatric emergencies during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the suburban New York City area. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.M.; Rufino, K.; Kurian, S.; Saxena, J.; Saxena, K.; Williams, L. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020029280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibeziako, P.; Kaufman, K.; Scheer, K.N.; Sideridis, G. Pediatric Mental Health Presentations and Boarding: First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantos, J.D.; Yeh, H.W.; Raza, F.; Connelly, M.; Goggin, K.; Sullivant, S.A. Suicide Risk in Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021053486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, J.; Zettl, R. 44.9 Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Suicide Attempts and Suicidal Ideations in Youth. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Hong, J.S. Short- and Long-Term Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Suicide-Related Mental Health in Korean Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz de Neira, M.; Blasco-Fontecilla, H.; García, L.; Pérez-Balaguer, A.; Mallol, L.; Forti, A.; Del Sol, P.; Palanca, I. Demand Analysis of a Psychiatric Emergency Room and an Adolescent Acute Inpatient Unit in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Madrid, Spain. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 557508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, R.; Pamias, M.; Mortier, P.; Alonso, J.; Pérez, V.; Palao, D. Is the COVID-19 pandemic a risk factor for suicide attempts in adolescent girls? J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorca-Bofí, V.; Adrados-Pérez, M.; Sánchez-Cazalilla, M.; Torterolo, G.; Arenas-Pijoan, L.; Buil-Reiné, E.; Nicolau-Subires, E.; Albert-Porcar, C.; Ibarra-Pertusa, L.; Puigdevall-Ruestes, M.; et al. Urgent care and suicidal behavior in the child and adolescent population in a psychiatric emergency department in a Spanish province during the two COVID-19 states of alarm. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2022, 16, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-López, P.; Armero-Pedreira, P.; Martínez-Sánchez, L.; García-Cruz, J.M.; Bonetde-Luna, C.; Notario-Herrero, F.; Sánchez-Vázquez, A.R.; Rodríguez-Hernández, P.J.; Díez-Suárez, A. Self-injury and suicidal behavior in children and youth population: Learning from the pandemic. An. Pediatr. 2023, 98, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Mao, X.; Shao, X.; Liu, F.; Dong, W.; Cai, W. Suicidality and Its Associated Factors Among Students in Rural China During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparative Study of Left-Behind and Non-Left-Behind Children. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 708305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.Y.; Mao, X.F.; Dong, W.; Cai, W.P.; Deng, G.H. Prevalence of and factors associated with mental health problems and suicidality among senior high school students in rural China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Fang, J.; Wan, Y.; Tao, F.; Sun, Y. Assessment of Mental Health of Chinese Primary School Students before and after School Closing and Opening during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2021482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojica, C.M.; Hoyos, L.K.; Vanegas, H.S.; Muñoz, L.D.; Fernádez, D.G. Intento de suicidio pediátrico e ingreso a Unidad de Cuidado Intensivos, antes y después de la pandemia, en un hospital universitario en Boyacá, Colombia. Pediatria 2023, 56, e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RodrÃguez, U.E.; León, Z.L.; Ceballos, G.A. Ideación suicida, ansiedad, capital social y calidad de sueño en colombianos durante el primer mes de aislamiento físico por COVID-19. Psicogente 2020, 24, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamón, M.J.; Javela, J.J.; Vinaccia, S.; Matar-Khalil, S.; Cabezas-Corcione, A.; Cuesta, E.E. Risk and Protective Factors in Ecuadorian Adolescent Survivors of Suicide. Children 2023, 10, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiza, C.E.C.; Yero, J.C.P.; Ineráty, M.P.; Miguel, B.C. Suicide in teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Cuba: Actions for its prevention. J. Community Med. Health Solut. 2021, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, D.E.; Ochoa, L.J.; Orzuza, N.J.; Fernández, M.; Morra, A.P.; Castro, J.; Bedano, F.M.; Ferrando, F.; Bernasconi, S.V.; Turriani, M.; et al. Consultas por intentos de suicidio durante el primer año de pandemia por COVID-19: Estudio en cuatro provincias de Argentina. Rev. Argent. Salud Publica 2022, 14, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Pereyra, E.; Santillán, M.M. High school students suicide attempts and factors associated. A comparative analysis in Argentina and Bolivia. Stud. Politicae 2022, 58, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Campillo, C.; Fajardo-Dolci, G. Prevención del suicidio y la conducta suicida. Gac. Med. Mex. 2021, 157, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.; Benjet, C.; Orozco, R.; Medina-Mora, M.E. The growth of suicide ideation, plan and attempt among young adults in the Mexico City metropolitan area. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, E. Suicidio: El impacto del COVID-19 en la salud mental. Med. Y Ética 2021, 32, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Santiago, R.; Villalobos, A.; Arenas-Monreal, L.; González-Forteza, C.; Hermosillo-de-la-Torre, A.E.; Benjet, C.; Wagner, F.A. Comparative Analysis of Lifetime Suicide Attempts among Mexican Adolescents, over the Past 12 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Rivera, L.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Séris-Martínez, M.; Vázquez-Salas, A.; Reynales-Shigematsu, L.M. Prevalencia y factores psicológicos asociados con conducta suicida en adolescentes. Ensanut 2018–2019. Salud Publica Mex 2020, 62, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.; Romero-Martínez, M.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Cuevas- Nasu, L.; Bautista-Arredondo, S. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2021 Sobre COVID-19. Resultados Nacionales, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública: Cuernavaca, Morelos, México, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 11–300. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez-Santiago, R.; Villalobos-Hernández, A.; Arenas-Monreal, L.; Benjet, C.; Vázquez, A. Conducta suicida en México: Análisis comparativo entre población adolescente y adulta. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, K.M.; Kellerman, J.K.; Kleiman, E.M.; Bleidorn, W.; Hopwood, C.J.; Robins, R.W. The role of temperament in the onset of suicidal ideation and behaviors across adolescence: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 122, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.D.; Kowalchuk, B. Adolescent Inventory of Suicide Orientation-30, 1st ed.; National Computer Systems: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1994; Volume 1, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Piersma, H.L.; Boes, J.L. Utility of the inventory of suicide orientation-30 (ISO-30) for adolescent psychiatric inpatients: Linking clinical decision making with outcome evaluation. J. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 53, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Casullo, M.M. Validación factorial de una escala para evaluar riesgo suicida. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Y Eval. E Avaliação Psicol. 2006, 21, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua-Suárez, R.E.; González-Posada, C.M.; Rueda-Ramírez, S.M. Validation of the Spanish Version of the Inventory of Suicide Orientation—ISO 30 in Adolescent Students of Educational Institutions in Medellin—Colombia. World J. Educ. 2016, 6, p22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, L.M.; Avendaño, M.C.; Duarte, Z.J.; Campo-Arias, A. Consistencia interna y análisis de factores de la escala APGAR para evaluar el funcionamiento familiar en estudiantes de básica secundaria. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2006, 35, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Castilla, H.; Caycho, T.; Ventrura, J.L.; Palomino, M.; de la Cruz, M. Análisis factorial confirmatorio de la escala de percepción del funcionamiento familiar de Smilkstein en adolescentes peruanos. Salud Soc. 2016, 6, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. Children Depression Inventory CDI (Manual); Multihealth Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, A.D.; Cardona, D.; Cardona, J.A. Quality of life and depressive symptomatology in vulnerable adolescent women. Behav. Psychol. 2017, 25, 563–580. [Google Scholar]

- Posada, A.; Rúa, C. Validación del Instrumento Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Para Detección de Sintomatología Depresiva en Adolescentes; Universidad de Antioquia: Medellín, Colombia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C.A.; Rajmil, L.; Espinoza, R.M. Adaptación transcultural del cuestionario KIDSCREEN para medir calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en población mexicana de 8 a 18 años. Ciênc. Saude Colet. 2014, 19, 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.; Villagra, H.A.; Moya, J.M.; del Campo, J.; Pires, R. Health-related quality of life in Latin American adolescents. Rev. Panam. Public Health 2014, 35, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez, R.; López, S.; Rajmil, L. Género y salud percibida en la infancia y la adolescencia en España. Gac. Sanit. 2009, 23, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, M.A.; Jaik, A. Cuestionario para la Exploración del Bullying [Questionnaire for the Exploration of Bullying]. Rev. Vis. Educ. IUANES 2011, 5, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Lozano, M. Relación entre ansiedad social y victimización por acoso escolar. Rev. Educ. Hekademos 2021, 31, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Plutchik, R.; Van Praag, H. The measurement of suicidality, aggressivity and impulsivity. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1989, 13, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez, F.; Jiménez-Genchi, A.; López, A.; Raull, J.P.; Ortega, H.; Nicolini, H. Estudio de Validez de la traducción al cestellano de la escala de impulsividad de Plutchik. Salud Ment. 1996, 19, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fresán, A.; Camarena, B.; González-Castro, T.B.; Tovilla-Zarate, C.A.; Juaréz-Rojop, I.E.; López-Narváez, L.; González-Ramón, A.E.; Hernández-Díaz, Y. Risk-factor differences for nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in Mexican psychiatric patients. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdert, E. The Adolescent Assessment/Referral System Manual. DHHS Publication No. (ADM)91-1735; National Institute on Drug Abuse, US Department of Health and Human Service: Rockville, MD, USA, 1991; pp. 91–1735. [Google Scholar]

- del Carmen Mariño, M.; González-Forteza, C.; Andrade, P.; Medina-Mora, M.E. Validación de un cuestionario para detectar adolescentes con problemas por el uso de drogas. Salud Ment. 1998, 21, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, S.M.; O’Grady, K.E.; Gryczynski, J.; Mitchell, S.G.; Kirk, A.; Schwartz, R.P. The concurrent validity of the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT) substance use/abuse subscale in adolescent patients in an urban federally qualified health center. Subst. Abus. 2017, 38, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, A.; Patiño, M.L.; Guerrero, A.; León, B.; Centros de integración Juvenil, A.C. Manual Para la Aplicación del Cuestionario de Tamizaje de Problemas en Adolescentes (POSIT); UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, L.A.; Cardona-Duque, D.V.; Medina-Pérez, O.A.; Garzón-Olivera, L.F.; Garzón-Borray, H.A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, N.S. Riesgo suicida en población carcelaria del Tolima, Colombia. Rev. Fac. Med. 2014, 62, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathematical Psychology through Its Text. [Virtual Exhibition] Principal Component Analysis versus Factor Analysis. 2013. Available online: https://uam.es/biblioteca/psicologia/exposiciones/psicologiamatematica/psicologiamatematica_polemicas.html (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Godoy, J.L.; Vega, J.R.; Marchetti, J.L. Relationships between PCA and PLS-regression. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2014, 130, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, M.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Colchero, M.A.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Martínez-Barnetche, J.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.; Gómez-Acosta, L.M. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2023: Metodología y avances de la Ensanut Continua 2020–2024. Salud Pública México 2023, 65, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilkstein, G.; Ashworth, C.; Montano, D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J. Fam. Pract. 1982, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arenas-Monreal, L.; Hidalgo-Solórzano, E.; Chong-Escudero, X.; Durán-De la Cruz, J.A.; González-Cruz, N.L.; Pérez-Matus, S.; Valdez-Santiago, R. Suicidal behaviour in adolescents: Educational interventions in Mexico. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, K.; Balaban, J.; Shubkin, C.D. Adolescent suicide: What can pediatricians do? Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, M.L.; Dávila, C.A. Adolescentes en riesgo: Factores asociados con el intento de suicidio en México. Gerenc. Y Políticas Salud 2018, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, B.P.; Levins, B.H. Youth Suicide. Focus 2022, 20, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione, C.M.; Barry, M.J.; Nicholson, W.K.; Cabana, M.; Chelmow, D.; Coker, T.R.; Davidson, K.W.; Davis, E.M.; Donahue, K.E.; Jaén, C.R.; et al. Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents. JAMA 2022, 328, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Hurtado, O.L.; Gómez-Jaramillo, N.; Criado-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Pérez, J.; Sancho-Sánchez, C.; Sánchez-Barba, M.; Tejada-Garrido, C.I.; Criado-Pérez, L.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Santolalla-Arnedo, I.; et al. Exploring the Link between Interoceptive Body Awareness and Suicidal Orientation in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruch, D.A.; Heck, K.M.; Sheftall, A.H.; Fontanella, C.A.; Stevens, J.; Zhu, M.; Horowitz, L.M.; Campo, J.V.; Bridge, J.A. Characteristics and Precipitating Circumstances of Suicide Among Children Aged 5 to 11 Years in the United States, 2013–2017. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2115683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursul, A.; Herrera, E.; Galván, G. Riesgo de suicidio en adolescentes escolarizados. Psicogente 2022, 25, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamarro, A.; Díaz-Moreno, A.; Bonilla, I.; Cladellas, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gómez-Romero, M.J.; Limonero, J.T. Stress and suicide risk among adolescents: The role of problematic internet use, gaming disorder and emotional regulation. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, C.; Gómez, A.S.; Moreno, J.H.; Agudelo, M.P.; Caballo, V.E. Predictive Model of Suicide Risk in Young People: The Mediating Role of Alcohol Consumption. Arch. Suicide Res. 2023, 27, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Tabares, A.S.; Mogollón, E.M.; Clavijo, F.J.; Nuñez, C. El efecto predictor de la inteligencia emocional sobre el riesgo de ideación y conducta suicida en adolescentes colombianos. Behav. Psychol./Psicol. Coonductual 2023, 30, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, M.; Delaney, K.; Limandri, B.; Dreves, K.; Tipton, M.V.; Horowitz, L.M. Youth suicide risk screening in an outpatient child abuse clinic. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 35, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.C.; Fong, S.B.; Godoy, J.C. Suicidal risk and impulsivity-related traits among young Argentinean college students during a quarantine of up to 103-day duration: Longitudinal evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2021, 51, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Delgado, G.; Suárez, A.A.G.; Núñez, R.P. Education And Prevention: Strategies To Prevent Adolescent Suicide. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 13, 1711–1721. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, G.; Ramírez, J.E. Caracterización de estudiantes del Sistema de Educación Media Superior con riesgo de suicidio. In Perspectivas y Paradigmas en Psicología Aplicada, 1st ed.; Universidad Continental: Huancayo, Perú, 2023; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, D.L.; Benítez, V.; Casillas, F.R.; Leal, E.; Medina, R.A.; Cortés, R.G. Riesgo de suicidio en estudiantes de una preparatoria de Tepic, Nayarit; México. Rev. Salud Y Bienestar Social. 2022, 6, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ardiles-Irarrázabal, R.A.; Alfaro-Robles, P.A.; Díaz-Mancilla, I.E.; Martínez-Guzmán, V.V. Riesgo de suicidio adolescente en localidades urbanas y rurales por género, región de Coquimbo, Chile. Aquichan 2018, 18, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarch, J.; Chuluunbaatar, B.; Batbaatar, S.; Paulik, E. Suicide Attempts among School-Attending Adolescents in Mongolia: Associated Factors and Gender Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta, I.; Montesó-Curto, P.; Metzler, E.; Jiménez-Herrera, M.; Puig-Llobet, M.; Seabra, P.; Toussaint, L. Risk factors for teen suicide and bullying: An international integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2021, 27, e12930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, L.L.; Lee, J.; Rahmandar, M.H.; Sigel, E.J. Suicide and Suicide Risk in Adolescents. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023064800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda-Mendizabal, A.; Castellví, P.; Parés-Badell, O.; Alayo, I.; Almenara, J.; Alonso, I.; Blasco, M.J.; Cebrià, A.; Gabilondo, A.; Gili, M.; et al. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, A.A. Understanding suicide from a gender perspective: A critical literature review. Rev. Asoc. Esp. Neuropsiquiatr. 2019, 39, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Villar-Cabeza, F.; Lombardini, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, B.; Vila-Grifoll, M.; Esnaola-Letemendia, E.; Vergé-Muñoz, M.; Navarro-Masfisis, M.C.; Castellano-Tejedor, C. Gender differences in adolescents with suicidal behaviour: Personality and psychopathology. Rev. Psicol. Clín. Con Niños Y Adolesc. 2022, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equihua, O.J.; Sánchez, L.M.; Vargas, M.d.L.; Méndez, P. Suicidio en comunidades rurales de América Latina y el resto del mundo—Revisión. Uaricha Rev. Psicol. 2018, 15, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Londoño, C. Aportes a la comprensión y prevención del suicidio en población indígena: Una revisión sistemática narrativa. Psicol. Y Salud 2022, 33, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troya, C.; Tufiño, A.; Herrera, D.; Tulcanaz, K. El intento suicida en zonas rurales como un desafío a los modelos explicativos vigentes: Discusión de una serie de casos. Práctica Fam. Rural 2019, 4, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Olmos, I.; Cruz, D.L.T.; Traslaviña, Á.L.V.; Ibáñez-Pinilla, M. Caracterización de factores asociados con comportamiento suicida en adolescentes estudiantes de octavo grado, en tres colegios bogotanos. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2012, 41, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gijzen, M.W.M.; Rasing, S.P.A.; Creemers, D.H.M.; Smit, F.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; De Beurs, D. Suicide ideation as a symptom of adolescent depression. a network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 278, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossberg, A.; Rice, T. Depression and Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 107, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, S.; Marais, I.; Kyron, M.; Lawrence, D.; Page, A.C.; Gunasekera, S.; Glasgow, K.; Macqueen, L. Screening for depressive symptoms in adolescence: A Rasch analysis of the short-form childhood depression inventory-2 (CDI 2:SR[S]). J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 311, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Avenevoli, S. Epidemiology of Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. In Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 657–704. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, M.D.S.V.; Mendonça, C.R.; da Silva, T.M.V.; Noll, P.R.E.S.; de Abreu, L.C.; Noll, M. Relationship between depression and quality of life among students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, A.R.; Hostutler, C.A.; Beck, K.; Fontanella, C.A.; Bridge, J.A. Depression and Suicide-Risk Screening Results in Pediatric Primary Care. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021049999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; et al. The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 321, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Ye, Z.; Xie, J. Descriptive analysis of depression among adolescents in Huangshi, China. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Jia, Y.J.; Hu, F.H.; Ge, M.W.; Cheng, Y.J.; Qu, X.; Chen, H.L. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and correlated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 113 studies from 31 countries. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 166, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozuelo, J.R.; Desborough, L.; Stein, A.; Cipriani, A. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: Depressive Symptoms and Risky Behaviors Among Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 61, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Sánchez, F.A.; Brambila-Tapia, A.J.L.; Cárdenas-Fujita, L.S.; Toledo-Lozano, C.G.; Samudio-Cruz, M.A.; Gómez-Díaz, B.; García, S.; Rodríguez-Arellano, M.E.; Zamora-González, E.O.; López-Hernández, L.B. Family Functioning and Suicide Attempts in Mexican Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, D.C.R.; Preuss, L.J.; King, C.A. Suicidal Adolescents’ Social Support from Family and Peers: Gender-Specific Associations with Psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2006, 34, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.M. Development of Structural Model on Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents’ Exposure to Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, L.G.; Flisher, A.J.; Lombard, C. Suicidal ideation and attempts in adolescents: Associations with depression and six domains of self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2004, 27, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, S.Y. Perceived family functioning and suicidal ideation: Hopelessness as mediator or moderator. Nurs. Res. 2011, 60, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sun, Z.; Yang, Y. Parent-reported suicidal behavior and correlates among adolescents in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 105, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, J.J.; Llorente, C.; Kehrmann, L.; Flamarique, I.; Zuddas, A.; Purper-Ouakil, D.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Coghill, D.; Schulze, U.M.E.; Dittmann, R.W.; et al. Psychosocial risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D.M.; Mathias, C.W.; Marsh-Richard, D.M.; Prevette, K.N.; Dawes, M.A.; Hatzis, E.S.; Palmes, G.; Nouvion, S.O. Impulsivity and clinical symptoms among adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury with or without attempted suicide. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 169, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, H.A.; Kim, K.L.; Seymour, K.E.; Wolff, J.; Esposito-Smythers, C.; Spirito, A.; Dickstein, D.P. Cognitive Flexibility and Impulsivity Deficits in Suicidal Adolescents. Res. Child. Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022, 50, 1643–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, J.; Lamis, D.A.; Wang, Y. Risk Assessment on Suicide Death and Attempt among Chinese Rural Youths Aged 15–34 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, S.; Anconetani, G.; Rogier, G.; Del Casale, A.; Pompili, M.; Velotti, P. Impulsivity traits and suicide related outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis using the UPPS model. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C.; Martín, A.H.S. Comportamientos de riesgo de suicidio y calidad de vida, por género, en adolescentes mexicanos, estudiantes de preparatoria. Ciênc. Saude Colet. 2015, 20, 3437–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Kawachi, I.; Almansa, J.; von Steinbüchel, N. Longitudinal changes in health-related quality of life in children with migrant backgrounds. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobari, H.; Fashi, M.; Eskandari, A.; Villafaina, S.; Murillo-Garcia, Á.; Pérez-Gómez, J. Effect of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents and Children: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C.A.; Chávez-Flores, Y.V.; Yanez-Peñúñuri, L.Y.; Navarro, S.R.M. Comportamientos de riesgo de suicidio y calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en estudiantes que ingresaron a una universidad mexicana. Ciênc. Saude Colet. 2019, 24, 3763–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasdalsmoen, M.; Eriksen, H.R.; Lønning, K.J.; Sivertsen, B. Physical exercise, mental health problems, and suicide attempts in university students. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, E.L.; Boisen, K.A.; Andersen, A.; Jørgensen, S.E.; Teilmann, G.; Michelsen, S.I. Low Level of Well-being in Young People with Physical-Mental Multimorbidity: A Population-Based Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 73, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jang, H. Correlations between suicide rates and the prevalence of suicide risk factors among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, E.; Berk, M.S.; Asarnow, J.R.; Adrian, M.; Cohen, J.; Korslund, K.; Avina, C.; Hughes, J.; Harned, M.; Gallop, R.; et al. Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents at High Risk for Suicide. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falgares, G.; Marchetti, D.; De Santis, S.; Carrozzino, D.; Kopala-Sibley, D.C.; Fulcheri, M.; Verrocchio, M.C. Attachment Styles and Suicide-Related Behaviors in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Self-Criticism and Dependency. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C.; Pratt, D.; Kilshaw, M.; Ward, K.; Kelly, J.; Haddock, G. The relationship between self-criticism and suicide probability. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Qiu, X.; Yang, X.; Qiao, Z.; Song, X.; Zhao, E. Social Support and Suicide Risk Among Chinese University Students: A Mental Health Perspective. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 566993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.K.; Barton, A.L. Positive Social Support, Negative Social Exchanges, and Suicidal Behavior in College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M. School poverty and the risk of attempted suicide among adolescents. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desseilles, M.; Perroud, N.; Guillaume, S.; Jaussent, I.; Genty, C.; Malafosse, A.; Courtet, P. Is it valid to measure suicidal ideation by depression rating scales? J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Ji, L.; Chen, C.; Hou, B.; Ren, D.; Yuan, F.; Liu, L.; Bi, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, N.; et al. College students’ screening early warning factors in identification of suicide risk. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 977007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, B.; Cohen, A.; Khoury, E.; Trebossen, V.; Bouchlaghem, N.; Poncet-Kalifa, H.; Acquaviva, E.; Lefebvre, A.; Delorme, r. Emotional and behavioral changes in French children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materu, J.; Kuringe, E.; Nyato, D.; Galishi, A.; Mwanamsangu, A.; Katebalila, M.; Shao, A.; Changalucha, J.; Nnko, S.; Wambura, M. The psychometric properties of PHQ-4 anxiety and depression screening scale among out-of-school adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Spears, M.R.; Montgomery, A.A.; Millings, A.; Sayal, K.; Stallard, P. Could a brief assessment of negative emotions and self-esteem identify adolescents at current and future risk of self-harm in the community? A prospective cohort analysis. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizli Çoban, Ö.; Gül, M.E.; Önder, A. Evaluation of Children and Adolescents Admitted to Emergency Service with Suicide Attempt. Turk. J. Pediatr. Emerg. Intensive Care Med. 2022, 9, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defayette, A.B.; Adams, L.M.; Whitmyre, E.D.; Williams, C.A.; Esposito-Smythers, C. Characteristics of a First Suicide Attempt that Distinguish Between Adolescents Who Make Single Versus Multiple Attempts. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øien-Ødegaard, C.; Hauge, L.J.; Reneflot, A. Marital status, educational attainment, and suicide risk: A Norwegian register-based population study. Popul. Health Metr. 2021, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro-Cañizares, I.; Sánchez-Colorado, N.; Baca-García, E.; Carballo, J.J. Perceived Stressful Life Events and Suicide Risk in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Perceived Family Functioning. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, N.B.I.; Mendieta, Z.; Juárez, N.E.; Castrejón, R. Ideación suicida y su asociación con el apoyo social percibido en adolescentes. Aten. Fam. 2020, 27, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Wright, E.P.; Dedding, C.; Pham, T.T.; Bunders, J. Low Self-Esteem and Its Association With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Vietnamese Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, O.; Kuja-Halkola, R.; Bjureberg, J.; Ohlis, A.; Cederlöf, M.; Norén Selinus, E.; Lichtenstein, P.; Larsson, H.; Lundström, S.; Hellner, C. Associations of impulsivity, hyperactivity, and inattention with nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: Longitudinal cohort study following children at risk for neurodevelopmental disorders into mid-adolescence. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Soto, P.; Games-Díaz, L.; Ramírez-Santana, M. Characterization of suicidal behavior in Coquimbo, Chile, between 2018 and 2020. Medwave 2024, 24, e2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Full Sample Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | WHS Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | HS14 Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | RHSPV Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | RHST Mean ± SD (Min–Max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 3584 | 127 | 840 | 900 | 1716 |

| Age | 15.7 ± 1 (14–22) | 16.2 ± 1 (14–20) | 15.9 ± 1 (14–22) | 15.9 ± 0.9 (14–19) | 15.7 ± 1(15–20) |

| Female | 2317 | 68 | 541 | 588 | 1120 |

| Male | 1266 | 59 | 299 | 312 | 596 |

| ISO-30 | 30.3 ± 15.4 (0–85) | 37.6 ± 9.1 (9–62) | 30.7 ± 16.2 (2–83) | 31.7 ± 16 (3–85) | 28.8 ± 14 (0–84) |

| Dimension ISO-30 | |||||

| LSE | 5.9 ± 3.5 (0–18) | 8.4 ± 2.7 (2–16) | 5.8 ± 3.6 (0–16) | 6.1 ± 3.6 (0–18) | 5.5 ± 3.4 (0–18) |

| ICE | 8.5 ± 3.1 (0–18) | 9.5 ± 2.3 (3–16) | 8.4 ± 3.1 (0–18) | 8.6 ± 3.3 (0–17) | 8.4 ± 3.0 (0–18) |

| HPL | 5.3 ± 3.3 (0–18) | 6.4 ± 2.7 (0–15) | 5.5 ± 3.4 (0–17) | 5.4 ± 3.5 (0–18) | 5.0 ± 3.2 (0–17) |

| SIW | 6.6 ± 4.4 (0–18) | 6.7 ± 3.0 (0–14) | 6.8 ± 4.6 (0–18) | 7.1 ± 4.5 (0–18) | 6.1 ± 4.3 (0–18) |

| SUI | 3.9 ± 3.7 (0–18) | 6.3 ± 3.7 (0–17) | 4.1 ± 3.9 (0–18) | 4.2 ± 4.0 (0–18) | 3.2 ± 3.4 (0–18) |

| Gender | Variables | Full Sample Mean ± SD t-S | WHS Mean ± SD t-S | HS14 Mean ± SD t-S | RHSPV Mean ± SD t-S | RHST Mean ± SD t-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fem/Mal | ISO-30 | 32.4 ± 16.0/26.4 ± 13.5 p ≤ 0.001 | 38.9 ± 9.9/36.1 ± 7.9 p = 0.069 | 32.8 ± 16.5/27.0 ± 15 p ≤ 0.001 | 35.1 ± 16.9/25.4 ± 13.2 p ≤ 0.001) | 30.5 ± 15.2/25.5 ± 13.0 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Fem/Mal | LSE | 6.1 ± 3.7/5.4 ± 3.3 p ≤ 0.001 | 8.8 ± 3.0/8.0 ± 2.3 p = 0.061 | 6.1 ± 3.7/5.4 ± 3.5 p = 0.012 | 6.6 ± 3.7/5.3 ± 3.1 p ≤ 0.001 | 5.7 ± 3.5/5.3 ± 3.2 p = 0.045 |

| Fem/Mal | ICE | 9.0 ± 3.1/7.7 ± 2.9 p ≤ 0.001 | 9.8 ± 2.3/9.3 ± 2.2 p = 0.392 | 8.8 ± 3.1/7.6 ± 3.1 p ≤ 0.001 | 9.3 ± 3.2/7.4 ± 3.0 p ≤ 0.001 | 8.8 ± 3.0/7.7 ± 2.8 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Fem/Mal | HPL | 5.7 ± 3.4/4.6 ± 3.1 p ≤ 0.001 | 6.5 ± 2.6/6.3 ± 2.8 p = 0.679 | 5.8 ± 3.4/4.8 ± 3.2 p ≤ 0.001 | 6.0 ± 3.5/4.3 ± 3.0 p ≤ 0.001 | 5.4 ± 3.2/4.4 ± 3.1 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Fem/Mal | SIW | 7.2 ± 4.5/5.3 ± 3.8 p ≤ 0.001 | 7.0 ± 3.2/6.3 ± 2.8 p = 0.159 | 7.5 ± 4.7/5.5 ± 4.1 p ≤ 0.001 | 8.1 ± 4.6/5.3 ± 3.8 p ≤ 0.001 | 6.7 ± 4.4/5.1 ± 3.8 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Fem/Mal | SUI | 4.3 ± 3.9/3.3 ± 3.3 p ≤ 0.001 | 6.6 ± 4.0/6.0 ± 3.2 p = 0.519 | 4.4 ± 4.0/3.5 ± 3.4 p = 0.006 | 4.9 ± 4.3/2.9 ± 3.1 p ≤ 0.001 | 3.7 ± 3.5/3.0 ± 3.1 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | CV | Min/Max | Range | SB | KS | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO-30 | 61.01 | 8.8 | 14.4587% | 45/85 | 40.0 | 0.754 | −1.512 | |

| CDI | 25.99 | 9.33 | 35.9172% | 2/45 | 43.0 | −1.040 | −0.075 | <0.001 |

| POSIT | 32.65 | 10.5 | 32.3042% | 1/53 | 52.0 | −0.416 | −0.537 | 0.15 |

| SU/A | 1.225 | 2.15 | 176.282% | 0/8 | 8.0 | 9.059 | 6.856 | 0.51 |

| MH | 11.21 | 3.04 | 27.1839% | 0/15 | 15 | −4.406 | 3.143 | <0.001 |

| FR | 5.541 | 2.55 | 46.0743% | 1/10 | 9.0 | −0.956 | −2.198 | 0.06 |

| PR | 1.291 | 1.24 | 96.4755% | 0/5 | 5 | 3.482 | −0.569 | 0.51 |

| ES | 8.716 | 3.35 | 38.5024% | 0/14 | 14 | −2.046 | −1.221 | 0.63 |

| VS | 2.108 | 1.65 | 78.6962% | 0/6 | 6 | 0.471 | −2.360 | 0.51 |

| AB/D | 4.65 | 2.44 | 52.5775% | 0/10 | 10 | 1.322 | −1.452 | 0.06 |

| F APGAR | 3.466 | 2.88 | 83.364% | 0/10 | 10 | 2.682 | −1.435 | <0.001 |

| BULLIED | 1.327 | 0.29 | 22.3586% | 1/2.2 | 1.29 | 5.124 | 2.553 | 0.11 |

| BULLY | 1.090 | 0.16 | 14.9558% | 1/2 | 1.04 | 11.93 | 21.66 | 0.29 |

| BULL OBS | 1.491 | 0.51 | 34.2317% | 1/2.7 | 1.72 | 4.067 | −0.980 | <0.001 |

| IS | 22.89 | 5.56 | 24.2912% | 6/33 | 27.0 | −1.761 | −0.624 | <0.001 |

| HRQoL | 34.59 | 7.22 | 20.8857% | 22/59 | 36.4 | 4.274 | 2.529 | <0.001 |

| PHWB | 36.97 | 11.3 | 30.6352% | 15/64 | 48.9 | 2.504 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| PWB | 31.52 | 11.6 | 37.1052% | 10.7/59.4 | 48.7 | 1.023 | −0.594 | <0.001 |

| ME | 31.43 | 9.36 | 29.7816% | 12.8/63.1 | 50.3 | −0.276 | 0.744 | <0.001 |

| SP | 32.40 | 8.59 | 26.5223% | 20.2/64.3 | 44.1 | 5.814 | 4.520 | <0.001 |

| A | 34.96 | 10.2 | 29.2469% | 18/61.2 | 43.2 | 3.535 | 1.246 | 0.06 |

| PRHL | 32.24 | 15.4 | 47.8883% | 12.2/122 | 109.8 | 14.839 | 39.597 | 0.21 |

| FR | 40.07 | 11.0 | 27.5424% | 22/60.6 | 38.6 | 1.027 | −1.721 | 0.10 |

| SSP | 38.09 | 12.5 | 33.0614% | 12.4/63.7 | 51.3 | 1.086 | −1.015 | <0.001 |

| SE | 38.59 | 9.44 | 24.4759% | 23.5/62.2 | 38.7 | 1.877 | −1.149 | <0.001 |

| SA | 31.58 | 15.8 | 50.0398% | -7.6/56.3 | 63.9 | −0.339 | −1.872 | <0.001 |

| Suicidal Ideation and Behavior ISO-30 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Spearman’s Correlation | p-Value |

| CDI | 0.437 | 0.00 |

| POSIT | 0.152 | 0.09 |

| SU/A | −0.132 | 0.150 |

| MH | 0.310 | 0.00 |

| FR | 0.134 | 0.14 |

| PR | 0.017 | 0.85 |

| ES | 0.026 | 0.77 |

| VS | 0.045 | 0.62 |

| AB/D | 0.098 | 0.28 |

| F APGAR | −0.263 | 0.00 |

| BULLIED | 0.197 | 0.03 |

| BULLY | 0.176 | 0.05 |

| BULL OBS | 0.289 | 0.00 |

| IS | 0.265 | 0.00 |

| HRQoL | −0.433 | 0.00 |

| PHWB | −0.340 | 0.00 |

| PWB | −0.352 | 0.00 |

| ME | −0.371 | 0.00 |

| SP | −0.516 | 0.00 |

| A | −0.163 | 0.07 |

| PRHL | −0.224 | 0.01 |

| FR | −0.171 | 0.06 |

| SSP | −0.286 | 0.00 |

| SE | −0.198 | 0.03 |

| SA | −0.231 | 0.01 |

| Variables | Comp 1 | Comp 2 | Comp 3 | Comp 4 | Comp 5 | Comp 6 | Comp 7 | Comp 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 0.013 | 0.0524 | 0.046 | −0.157 | 0.613 | −0.018 | 0.226 | 0.248 |

| Gender | 0.010 | 0.047 | −0.097 | −0.233 | 0.470 | −0.143 | 0.217 | 0.217 |

| CDI | −0.263 | −0.065 | −0.070 | 0.158 | 0.297 | 0.065 | 0.175 | −0.087 |

| POSIT | −0.261 | 0.335 | −0.022 | 0.127 | −0.018 | −0.003 | −0.028 | −0.019 |

| SU/A | −0.086 | 0.320 | −0.054 | 0.161 | −0.173 | −0.005 | 0.120 | 0.276 |

| MH | −0.250 | 0.170 | −0.005 | 0.229 | 0.171 | −0.088 | 0.014 | −0.344 |

| FR | −0.217 | 0.195 | −0.060 | 0.003 | −0.053 | −0.069 | −0.416 | 0.254 |

| PR | −0.098 | 0.168 | 0.137 | −0.192 | −0.282 | −0.246 | 0.388 | 0.257 |

| ES | −0.198 | 0.269 | −0.035 | 0.104 | 0.116 | 0.141 | −0.000 | −0.296 |

| VS | −0.134 | 0.268 | 0.020 | −0.225 | 0.107 | 0.084 | −0.075 | −0.174 |

| AB/D | −0.150 | 0.322 | 0.002 | −0.129 | 0.091 | 0.045 | 0.177 | 0.006 |

| F APGAR | 0.228 | −0.187 | 0.020 | 0.092 | −0.010 | 0.187 | 0.296 | −0.239 |

| BULLIED | −0.101 | −0.048 | 0.531 | 0.139 | 0.046 | −0.126 | −0.041 | 0.063 |

| BULLY | −0.035 | −0.116 | 0.492 | 0.149 | −0.022 | 0.082 | 0.041 | 0.129 |

| BULL OBS | −0.100 | −0.038 | 0.522 | 0.066 | 0.126 | 0.046 | −0.066 | 0.122 |

| IS | −0.180 | 0.209 | 0.168 | 0.199 | −0.021 | 0.145 | 0.023 | −0.139 |

| HRQoL | 0.319 | 0.224 | 0.046 | 0.106 | 0.063 | 0.071 | −0.027 | 0.012 |

| PHWB | 0.256 | 0.209 | 0.022 | 0.030 | 0.013 | −0.369 | −0.130 | 0.060 |

| PWB | 0.286 | 0.176 | 0.126 | −0.081 | 0.059 | −0.220 | −0.077 | −0.204 |

| ME | 0.271 | 0.140 | 0.118 | −0.030 | 0.129 | −0.244 | −0.247 | −0.160 |

| SP | 0.233 | 0.256 | 0.067 | −0.126 | −0.050 | 0.072 | −0.076 | 0.066 |

| A | 0.208 | 0.205 | 0.149 | −0.008 | −0.063 | 0.324 | 0.090 | 0.023 |

| PRHL | 0.110 | 0.079 | 0.178 | −0.316 | −0.162 | 0.134 | 0.346 | −0.269 |

| FR | 0.227 | 0.113 | 0.015 | 0.309 | 0.209 | −0.007 | −0.016 | −0.163 |

| SSP | 0.183 | 0.241 | −0.122 | 0.260 | −0.027 | 0.065 | 0.264 | 0.119 |

| SE | 0.110 | −0.006 | −0.140 | 0.550 | −0.033 | −0090 | 0.189 | 0.233 |

| SA | 0.129 | 0.067 | −0.036 | −0.060 | 0.123 | 0.632 | 0.266 | 0.284 |

| %Variance | 26.74 | 15.24 | 8.92 | 6.38 | 5.14 | 4.89 | 4.1 | 3.98 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Err. | t-Stat. | p-Value | CI<95 | CI>95 | R2 | Adj R2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | 0.516 | 0.481 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Constant | 70.632 | 5.562 | 12.697 | 0.000 | 59.609 | 81.654 | |||

| Gender | 2.727 | 1.191 | 2.290 | 0.023 | 0.367 | 5.088 | |||

| CDI | 0.222 | 0.086 | 2.581 | 0.011 | 0.051 | 0.393 | |||

| POSIT | −0.407 | 0.093 | −4.356 | 0.000 | −0.592 | −0.222 | |||

| F APGAR | −1.090 | 0.294 | −3.699 | 0.000 | −1.674 | −0.506 | |||

| IS | 0.656 | 0.129 | 5.0709 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.913 | |||

| SP | −0.386 | 0.086 | −4.465 | 0.000 | −0.557 | −0.214 | |||

| PRHL | 0.104 | 0.041 | 2.503 | 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.186 | |||

| SE | −0.148 | 0.065 | −2.287 | 0.024 | −0.277 | −0.019 | |||

| Model II | 0.515 | 0.480 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Constant | 72.155 | 4.897 | 14.731 | 0.000 | 62.449 | 81.860 | |||

| SU/A | −0.988 | 0.348 | −2.833 | 0.005 | −1.679 | −0.297 | |||

| MH | 0.781 | 0.332 | 2.351 | 0.020 | 0.123 | 1.440 | |||

| ES | −1.071 | 0.280 | −3.820 | 0.000 | −1.626 | −0.515 | |||

| F APGAR | −0.619 | 0.257 | −2.407 | 0.017 | −1.130 | −0.109 | |||

| IS | 0.539 | 0.136 | 3.963 | 0.000 | 0.269 | 0.809 | |||

| SP | −0.460 | 0.080 | −5.736 | 0.000 | −0.619 | −0.301 | |||

| SSP | 0.159 | 0.066 | 2.396 | 0.018 | 0.027 | 0.291 | |||

| SE | −0.278 | 0.076 | −3.638 | 0.000 | −0.429 | −0.126− | |||

| Model III | 0.514 | 0.479 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Constant | 77.905 | 5.419 | 14.374 | 0.000 | 67.166 | 88.645 | |||

| MH | 0.998 | 0.321 | 3.106 | 0.002 | 0.361 | 1.634 | |||

| ES | −1.223 | 0.275 | −4.446 | 0.000 | −1.769 | −0.678 | |||

| BULLIED | −8.591 | 3.190 | −2.693 | 0.008 | −14.913 | −2.270 | |||

| BULL OBS | 5.874 | 1.875 | 3.132 | 0.002 | 2.158 | 9.591 | |||

| IS | 0.433 | 0.135 | 3.206 | 0.001 | 0.165 | 0.700 | |||

| SP | −0.524 | 0.080 | −6.524 | 0.000 | −0.683 | −0.365 | |||

| SSP | 0.127 | 0.064 | 1.96176 | 0.052 | −0.001 | 0.255 | |||

| SE | −0.325 | 0.075 | −4.31604 | 0.000 | −0.474 | −0.175 |

| Model | MSE | R-Squared | Adj.RSqr | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 0.403 | 0.516 | 0.481 | G, CDI, POSIT, F APGAR, IS, SP, PRHL, SE |

| II | 0.404 | 0.515 | 0.480 | SU/A, MH, ES, IS, SP, SSP, SE |

| III | 0.405 | 0.514 | 0.479 | MH, ES, BULLIED, BULL OBS, IS, SP, SSP, SE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez Delgado, G.; Ponce Rojo, A.; Ramírez Mireles, J.E.; Carmona-Moreno, F.d.J.; Flores Salcedo, C.C.; Hernández Romero, A.M. Suicide Risk Factors in High School Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081055

Gómez Delgado G, Ponce Rojo A, Ramírez Mireles JE, Carmona-Moreno FdJ, Flores Salcedo CC, Hernández Romero AM. Suicide Risk Factors in High School Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(8):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081055

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez Delgado, Guillermo, Antonio Ponce Rojo, Jaime Eduardo Ramírez Mireles, Felipe de Jesús Carmona-Moreno, Claudia Cecilia Flores Salcedo, and Aurea Mercedes Hernández Romero. 2024. "Suicide Risk Factors in High School Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 8: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081055

APA StyleGómez Delgado, G., Ponce Rojo, A., Ramírez Mireles, J. E., Carmona-Moreno, F. d. J., Flores Salcedo, C. C., & Hernández Romero, A. M. (2024). Suicide Risk Factors in High School Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081055