Navigating Real-World Randomized Clinical Trials: The ‘Parents as Teachers’ Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Significance of RCTs in Program Evaluation

1.2. Background of the Study

1.3. The AZ PAT RCT Study

- What has been the impact of participating in and helping conduct an RCT in the field?

- What are the perceived and demonstrated benefits of conducting an RCT?

- What motivated people to take part in the AZ PAT RCT study?

- What have been the most challenging aspects of the AZ PAT RCT study?

- What has worked well to mitigate these challenges?

- How well do stakeholders understand and accept the AZ PAT RCT?

- What can be recommended in terms of mitigating the impacts of RCT’s on communities?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Methods

2.2. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Interviewee Perspectives on RCT Benefits

- Building the evidence base for PAT.

- Enhancing program credibility for funders and potential implementers.

- Increasing the likelihood of additional funding to improve or expand program implementation.

3.2. Parent Educator Perspectives on RCT Benefits

- Over 90% agreed or strongly agreed that “There are useful benefits to a home visiting program being involved in an RCT study”.

- Similarly, over 90% agreed or strongly agreed that “The results of RCTs help home visiting programs improve in the long run”.

- The importance of research demonstrating the effectiveness of the PAT program was acknowledged as “very important” by 77% and “important” by 19% of Parent Educators surveyed.

- Regarding the importance of PAT being ‘evidence-based’ to the parents they work with, 48% said it was “very important”, and 39% said it was “important”.

- Furthermore, 71% of Parent Educators agreed or strongly agreed that “the benefits of an RCT study outweigh the burdens”.

3.3. Challenges and Complexities of RCTs

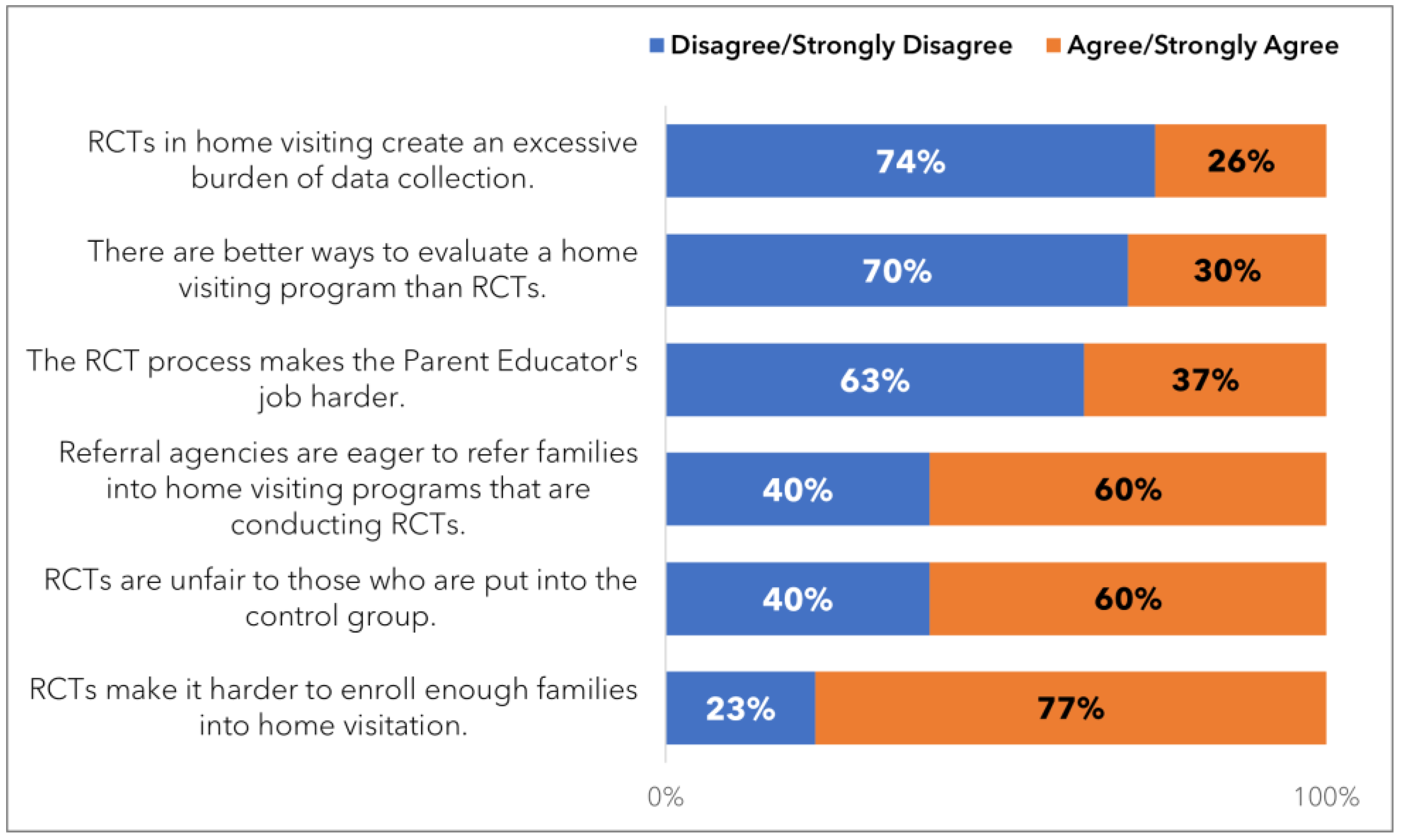

- Ethical Concerns: Mistrust and ethical concerns arise due to the random assignment of families to control groups, potentially denying some families access to services. A significant portion (60%) of Parent Educators surveyed believed that RCTs are unfair to those placed in the control group.

- Recruitment Challenges: RCTs necessitate a higher recruitment goal and pose difficulties in recruiting each family, as twice as many participants are required to ensure equal randomization. Parent Educators expressed concerns that RCTs make it harder to enroll enough families into home visitation programs; of all the challenges listed, this was the item with which there was the strongest agreement.

- Participant Confusion: Some parents may not fully understand the difference between the research data collection process and the intervention itself, leading to confusion when data collectors are involved in home visits.

- Challenges in Measuring Outcomes: Selecting outcomes to measure the impact of home visitation programs can be challenging due to the complex and multifaceted nature of the interventions and the broader environmental factors that affect families.

- External Factors: Contextual factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can significantly impact program implementation and data collection for RCTs, leading to additional challenges.

3.4. Strategies to Mitigate RCT Challenges

- Adjusting Randomization Ratio: To mitigate concerns about reduced program enrollment numbers, the randomization ratio was adjusted to 2:1 (PAT treatment group to control group), which helped maintain funding levels for program sites.

- Providing Limited Study Bypasses: The study introduced bypasses where agencies were given a set number of “opt outs” for the study, they were withdrawn from the study and received PAT services directly, addressing worker concerns about families not receiving services when needed.

- Offering Resources to Control Group: Control group families were provided with information on community resources similar to PAT services, reducing staff concerns about families not having access to services.

- Educating Stakeholders: Establishing trust and open communication with program staff and participants was crucial in encouraging cooperation with RCT requirements. Communication emphasized the benefits for both control and treatment groups.

- Incorporating Qualitative Methods: Qualitative methods and lived experience experts provided personal stories and perspectives that helped participants feel included and validated.

- Highlighting Benefits: Materials describing the AZ PAT RCT emphasized the benefits for both groups, aiming to make research participation empowering and beneficial for all participants.

3.5. Balancing Program Funding and Evidence

3.6. Alternative Evaluation Designs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Clinical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parents as Teachers. Parents as Teachers Model Goals; Parents as Teachers: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness. HHS Criteria for Evidence-Based Models. Available online: https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/about-us/hhs-criteria (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Li, W.; van Wely, M.; Gurrin, L.; Mol, B.W. Integrity of randomized controlled trials: Challenges and solutions. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielke, D.; Rohde, V. Randomized controlled trials—A critical re-appraisal. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 2085–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzi-Lessing, L. Behind from the Start: How America’s War on the Poor Is Harming Our Most Vulnerable Children; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough, D.B.; Shulha, L.M.; Hopson, R.K.; Caruthers, F.A. The Program Evaluation Standards: A Guide for Evaluators and Evaluation Users, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, C.E.; Weijer, C.; Brehaut, J.C.; Fergusson, D.A.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Horn, A.R.; Taljaard, M. Ethical issues in pragmatic randomized controlled trials: A review of the recent literature identifies gaps in ethical argumentation. BMC Med. Ethics 2018, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Ashby, D.; Feder, G.; Rudnicka, A.R. Lessons for cluster randomized trials in the twenty-first century: A systematic review of trials in primary care. Clin. Trials 2016, 13, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landsverk, J.; Brown, C.H.; Rolls Reutz, J.; Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M. Design and Analysis in Dissemination and Implementation Research (DADIR) Team. Design and analysis in dissemination and implementation research. In Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 225–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc, T.; Petticrew, M.; Welch, V.; Tugwell, P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bédécarrats, F.; Guérin, I.; Roubaud, F. Randomized Controlled Trials in the Field of Development; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Puffer, S.; Torgerson, D.J.; Watson, J. Evidence for risk of bias in cluster randomised trials: Review of recent trials published in three general medical journals. Br. Med. J. 2017, 335, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibbald, B.; Roland, M. Understanding controlled trials: Why are randomised controlled trials important? Br. Med. J. 1998, 316, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, H.C.; Periyakoil, V.S. Doing right by your patients. In Evidence Based Practice in Action: Bringing Clinical Science and Intervention; Dimidjian, S., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Method; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, K.; Bower, P.; Elliott, J.; MacLennan, G.; Newlands, R.S.N.; Ogden, M.; Treweek, S.P.; Wells, M.; Witham, M.D.; Young, B.; et al. Systematic techniques to enhance retention in randomized controlled trials: The STEER study protocol. Trials 2022, 19, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- White, H.; Sabarwal, S. Quasi-experimental design and methods. In Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation No. 8; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto, J. Randomistas evaluatiors? In Randomized Controlled Trials in the Field of Development; Bédécarrats, F., Guérin, I., Roubaud, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.J.; Campbell-Patten, C.E. Utilization-Focused Evaluation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Benefits of the AZ PAT RCT Study to Stakeholders | Stakeholder Quotes |

|---|---|

| Building the evidence base for PAT | - “Conducting RCTs resulted in getting onto various clearinghouses, which enabled in securing federal funding, such as SAMHSA’s clearing house, HomVee, and Family’s First Prevention Services act clearing house.” (PATNC) - “The idea that early childhood education being studied was exciting. It needs a deeper understanding of how it works, this study was big and had the potential to get national attention.” (Site Leader) |

| Credibility among potential benefactors or subsequent implementers | - “Seeing the benefits the RCT could bring to our own program and the understanding of how PAT influences families. The reason why we embarked on this study is to be able to have those benefits and be able to reflect those throughout, not just the state but the nation.” (Site Leader) - “I think there’s some new opinions about evaluations and community-based evaluations, but so many that’s seen as the gold standard, and we always want to be able to show the impact and effectiveness of Parents as Teachers when we’re dealing with funders and or implementers, and especially from the point of view with decision-makers legislators.” (National Office) |

| Securing additional funding | - “Many decisions are made by funders that are data-driven. It’s not just showing them a family and having them do their testament because sometimes that’s just one family. Maybe it will open doors for more funding, not just in Arizona but in other places. Being able to show and demonstrate with more updated information and data will be great for us, not just for our current programs but also for future funding.” (Site Leader) - “It is hard to get funding from particular streams if you have evidence that is not [from] an RCT.” (National Office) |

| Additional benefits to self and others | - “Being in the study helped me stay on top of program data.” (Site Leader) - “Really seeing how families that are being served and enrolled in the study are weathering the storm of COVID-19 a little bit easier.” (National Office) - “I like being in studies, you can give a voice to people.” (Treatment Group Parent) - “The questions helped me reflect more as myself as a mom, it made me feel like I was doing well.” (Control Group Parent) |

| Evaluation Standard | Potential Barrier to RCTs | PAT RCT Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Propriety | Parents’ concerns about being “used” as a research participant | Provided detailed informed consent, offered parents incentives, established exclusion criteria for families in most need. |

| Parents’ concerns about being denied services as members of the “control group” | Control group was provided resources to address requested needs. | |

| The neediest parents could be denied home visiting services | Home visiting set-asides for the neediest families (who were not included in the study) | |

| Feasibility | Too expensive and too difficult to enroll enough families into both the treatment and control groups | Enrolled two treatment participants for every control group participant |

| Accuracy | Differing rates of attrition among treatment and control groups | Will need to evaluate attrition rates with control and treatment |

| Control group could receive similar services elsewhere | All participants—treatment and control—are asked about various other services to control in the analysis. | |

| Intent-to-treat diluting findings | Explore conducting analyses for all intervention participants (standard intent-to-treat) and only for participants engaging in services to see if findings differ. | |

| Utility | Results are needed in a timeframe that a funder needs | Can be an issue when funders need more timely data than RCT’s can feasibly deliver |

| Utility/Feasibility | Unexpected, external factors can lead to difficulties running the program, administering the study, and/or interpreting the results. | The COVID-19 pandemic created profound stressors to families, and necessitated shifts from in-home to virtual visits from PAT Parent Educators as well as data collectors. The RCT evaluation not only took these changes into account, but initiated a sub-study of (1) the adaptations to the PAT implementation and (2) the impact of the pandemic on the PAT treatment recipients versus the control group |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

LeCroy, C.W.; Sullins, C. Navigating Real-World Randomized Clinical Trials: The ‘Parents as Teachers’ Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081082

LeCroy CW, Sullins C. Navigating Real-World Randomized Clinical Trials: The ‘Parents as Teachers’ Experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(8):1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081082

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeCroy, Craig W., and Carolyn Sullins. 2024. "Navigating Real-World Randomized Clinical Trials: The ‘Parents as Teachers’ Experience" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 8: 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081082

APA StyleLeCroy, C. W., & Sullins, C. (2024). Navigating Real-World Randomized Clinical Trials: The ‘Parents as Teachers’ Experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081082