Factors behind Antibiotic Therapy: A Survey of Primary Care Pediatricians in Lombardy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

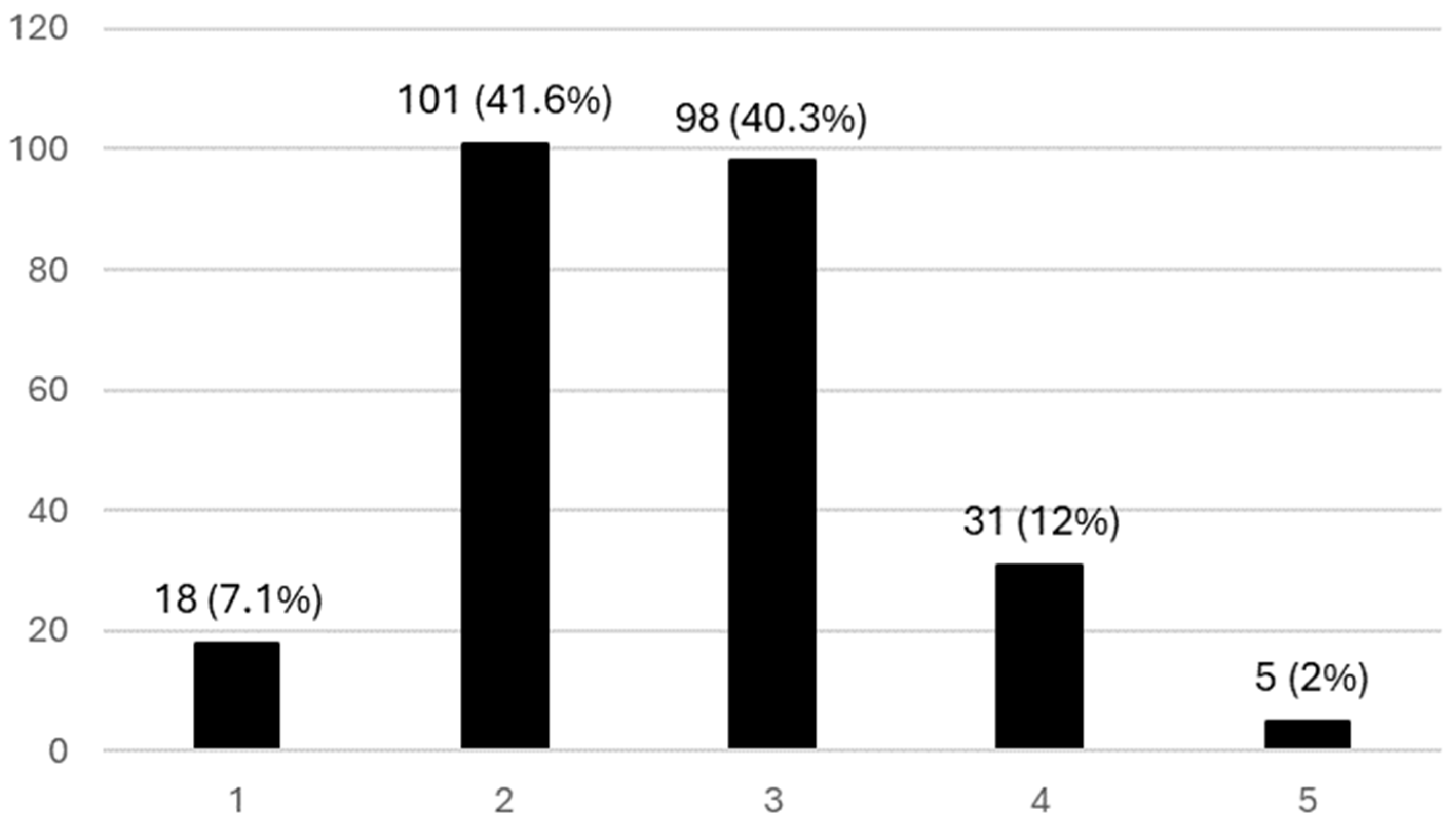

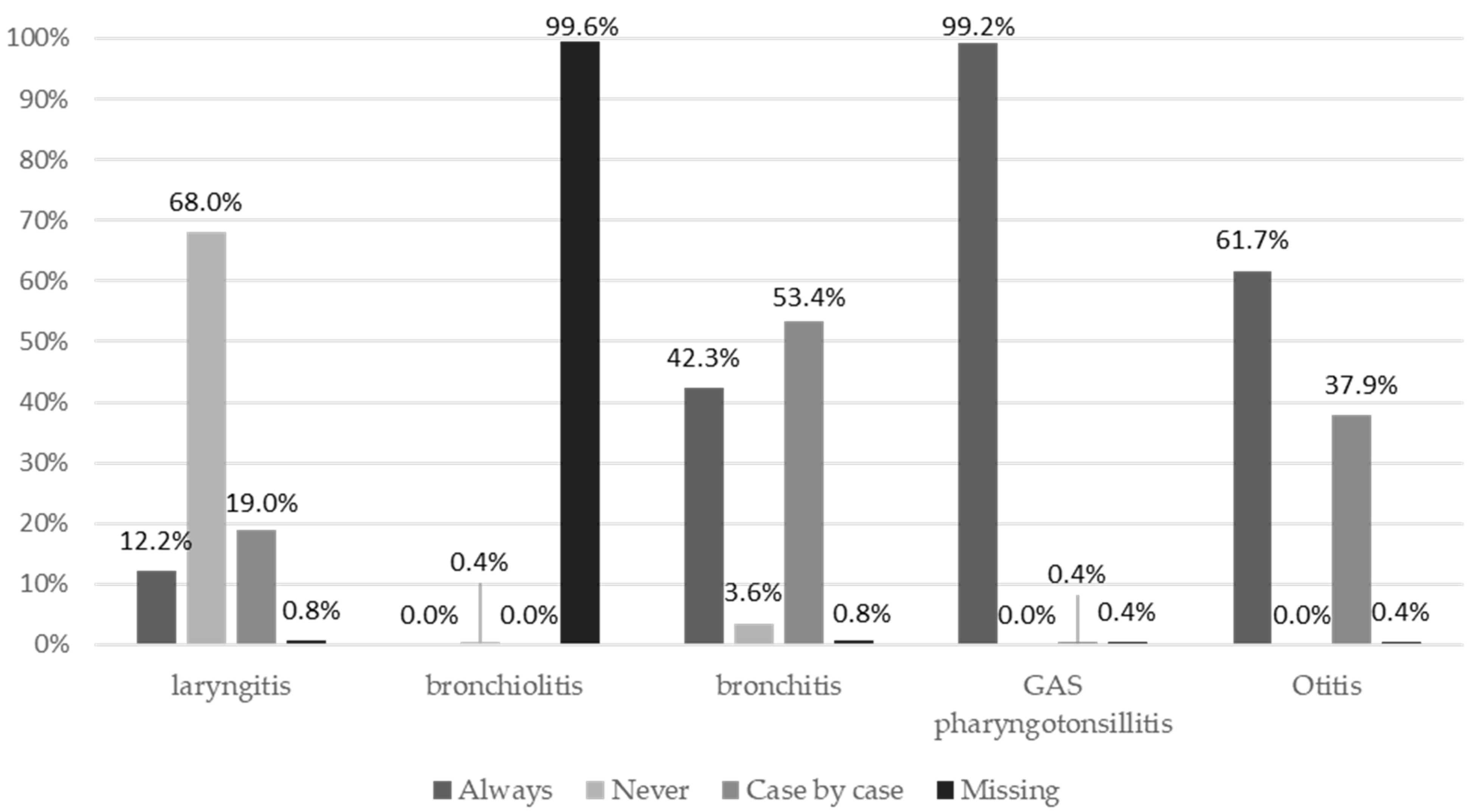

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20bacterial,development%20of%20drug%2Dresistant%20pathogens (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Castaldi, S.; Perrone, P.M.; Luconi, E.; Marano, G.; Auxilia, F.; Maraschini, A.; Bono, P.; Alagna, L.; Palomba, E.; Bandera, A.; et al. Hospital acquired infections in COVID-19 patients in sub intensive care unit: Analysis of two waves of admissions. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93, e2022313. [Google Scholar]

- Prigitano, A.; Perrone, P.M.; Esposto, M.C.; Carnevali, D.; De Nard, F.; Grimoldi, L.; Principi, N.; Cogliati, M.; Castaldi, S.; Romanò, L. ICU environmental surfaces are a reservoir of fungi: Species distribution in northern Italy. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 123, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, C.B. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: Principles and Practice. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 102, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, M.S. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship to reduce antimicrobial drug resistance. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2021, 19, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, A.; Duran, C.; Davido, B.; Bouchand, F.; Deconinck, L.; Matt, M.; Sénard, O.; Guyot, C.; Levasseur, A.S.; Attal, J.; et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship programme to optimize antimicrobial use for outpatients at an emergency department. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 97, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peragine, C.; Walker, S.A.N.; Simor, A.; Walker, S.E.; Kiss, A.; Leis, J.A. Impact of a comprehensive antimicrobial stewardship program on institutional burden of antimicrobial resistance: A 14-year controlled interrupted time-series study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2897–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallares, C.; Hernández-Gómez, C.; Appel, T.M.; Escandón, K.; Reyes, S.; Salcedo, S.; Matta, L.; Martínez, E.; Cobo, S.; Mora, L.; et al. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship programs on antibiotic consumption and antimicrobial resistance in four Colombian healthcare institutions. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiesh, B.M.; Nazzal, M.A.; Abdelhaq, A.I.; Abutaha, S.A.; Zyoud, S.H.; Sabateen, A. Impact of an antibiotic stewardship program on antibiotic utilization, bacterial susceptibilities, and cost of antibiotics. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timbrook, T.T.; Hurst, J.M.; Bosso, J.A. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on antimicrobial utilization, bacterial susceptibilities, and financial expenditures at an academic medical center. Hosp. Pharm. 2016, 51, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe/European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe 2022–2020 Data; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-europe-2022-2020-data (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità EpiCentro—L’epidemiologia per la Sanità Pubblica. Rapporto Nazionale 2021 “L’Uso degli antibiotici in Italia”. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/farmaci/report-aifa-antibiotici-2021#:~:text=Nel%202021%20il%2023%2C7,almeno%20una%20prescrizione%20di%20antibiotici (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Picca, M.; Carrozzo, R.; Milani, G.P.; Corsello, A.; Macchi, M.; Buzzetti, R.; Marchisio, P.; Mameli, C. Leading reasons for antibiotic prescriptions in pediatric respiratory infections: Influence of fever in a primary care setting. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2023, 49, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbom, M.; Büchner, F.L.; Saadah, N.H.; Numans, M.E.; De Boer, M.G.J. Determinants of inappropriate antibiotic prescription in primary care in developed countries with general practitioners as gatekeepers: A systematic review and construction of a framework. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X. Does diagnostic uncertainty increase antibiotic prescribing in primary care? NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2021, 31, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Wang, T.; Yin, J.; Sun, Q.; Dyar, O.J. Clinical Uncertainty Influences Antibiotic Prescribing for Upper Respiratory Tract Infections: A Qualitative Study of Township Hospital Physicians and Village Doctors in Rural Shandong Province, China. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Duan, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C. Coping with Diagnostic Uncertainty in Antibiotic Prescribing: A Latent Class Study of Primary Care Physicians in Hubei China. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 741345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, Q.; Enarson, P.; Kissoon, N.; Klassen, T.P.; Johnson, D.W. Rapid viral diagnosis for acute febrile respiratory illness in children in the Emergency Department. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 15, CD006452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedemark, S.A.; Aabenhus, R.; Llor, C.; Fournaise, A.; Olsen, O.; Jørgensen, K.J. Biomarkers as point-of-care tests to guide prescription of antibiotics in people with acute respiratory infections in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 10, CD010130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Lamb, M.M.; Moss, A.; Mistry, R.D.; Grice, K.; Ahmed, W.; Santos-Cantu, D.; Kitchen, E.; Patel, C.; Ferrari, I.; et al. Effect of Rapid Respiratory Virus Testing on Antibiotic Prescribing Among Children Presenting to the Emergency Department with Acute Respiratory Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2111836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.F.; Pauchard, J.Y.; Hjelm, N.; Cohen, R.; Chalumeau, M. Efficacy and safety of rapid tests to guide antibiotic prescriptions for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 6, CD012431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiter, T.; Hearing, M.; Bradic, S.; Coutinho, G.; Kostev, K. Reducing Antibiotic Misuse through the Use of Point-of-Care Tests in Germany: A Survey of 1257 Medical Practices. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallon, J.; Sundqvist, M.; Hedin, K. The use and usefulness of point-of-care tests in patients with pharyngotonsillitis—An observational study in primary health care. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebano, G.; Dyar, O.J.; Beovic, B.; Béraud, G.; Thilly, N.; Pulcini, C. Defensive medicine among antibiotic stewards: The international ESCMID AntibioLegalMap survey. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1989–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massano, G.A.; Cancrini, F.; Marsella, L.T. Antibiotic resistance and defensive medicine a modern challenge for an old problem, the Ureaplasma urealyticum case. Ig. E Sanita Pubblica 2014, 70, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Panthöfer, S. Do Doctors Prescribe Antibiotics Out of Fear of Malpractice? J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 2022, 19, 340–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, A.; Kirby, E.; Gibson, A.F.; Post, J.J.; Broom, J. Myth, Manners, and Medical Ritual: Defensive Medicine and the Fetish of Antibiotics. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 1994–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangione-Smith, R.; Mcglynn, E.A.; Elliott, M.N.; Krogstad, P.; Brook, R.H. The Relationship Between Perceived Parental Expectations and Pediatrician Antimicrobial Prescribing Behavior. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchner, H.; Pelton, S.I.; Klein, J.O. Parents, Physicians, and Antibiotic Use. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.S. What do patients expect from consultations for upper respiratory tract infections? Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangione-Smith, R.; Elliott, M.N.; Stivers, T.; McDonald, L.; Heritage, J.; McGlynn, E.A. Racial/ethnic variation in parent expectations for antibiotics: Implications for public health campaigns. Pediatrics 2004, 113, e385–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyar, O.J.; Hills, H.; Seitz, L.T.; Perry, A.; Ashiru-Oredope, D. Assessing the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of human and animal health students towards antibiotic use and resistance: A pilot cross-sectional study in the UK. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Vohra, C.; Raghav, P. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices about antibiotic resistance among medical students in India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rábano-Blanco, A.; Domínguez-Martís, E.M.; Mosteiro-Miguéns, D.G.; Freire-Garabal, M.; Novío, S. Nursing students’ knowledge and awareness of antibiotic use, resistance and stewardship: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyar, O.J.; Howard, P.; Nathwani, D.; Pulcini, C. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of French medical students about antibiotic prescribing and resistance. Med. Mal. Infect. 2013, 43, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuenchom, N.; Thamlikitkul, V.; Chaiwarith, R.; Deoisares, R.; Rattanaumpawan, P. Perception, attitude, and knowledge regarding antimicrobial resistance, appropriate antimicrobial use, and infection control among future medical practitioners: A multicenter study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Sánchez, E.; Drumright, L.N.; Gharbi, M.; Farrell, S.; Holmes, A.H. Mapping antimicrobial stewardship in undergraduate medical, dental, pharmacy, nursing and veterinary education in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecce, M.; Perrone, P.M.; Bonalumi, F.; Castaldi, S.; Cremonesi, M. 2020-21 influenza vaccination campaign strategy as a model for the third COVID-19 vaccine dose? Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021447. [Google Scholar]

- Maffeo, M.; Luconi, E.; Castrofino, A.; Campagnoli, E.M.; Cinnirella, A.; Fornaro, F.; Gallana, C.; Perrone, P.M.; Shishmintseva, V.; Pariani, E.; et al. 2019 Influenza Vaccination Campaign in an Italian Research and Teaching Hospital: Analysis of the Reasons for Its Failure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Arminio Monforte, A.; Tavelli, A.; Perrone, P.M.; Za, A.; Razzini, K.; Tomasoni, D.; Bordoni, V.; Romanò, L.; Orfeo, N.; Marchetti, G.; et al. Association between previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 and the risk of self-reported symptoms after mRNA BNT162b2 vaccination: Data from 3078 health care workers. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 36, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biganzoli, G.; Mendola, M.; Perrone, P.M.; Antonangeli, L.M.; Longo, A.B.E.; Carrer, P.; Colosio, C.; Consonni, D.; Marano, G.; Boracchi, P.; et al. The Effectiveness of the Third Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine: When Should It Be Performed? Vaccines 2024, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.M.; Biganzoli, G.; Lecce, M.; Campagnoli, E.M.; Castrofino, A.; Cinnirella, A.; Fornaro, F.; Gallana, C.; Grosso, F.M.; Maffeo, M.; et al. Influenza Vaccination Campaign during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Experience of a Research and Teaching Hospital in Milan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, P.M.; Villa, S.; Raciti, G.M.; Clementoni, L.; Vegro, V.; Scovenna, F.; Altavilla, A.; Tomoiaga, A.M.; Beltrami, V.; Bruno, I.; et al. Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination in 2023: A descriptive analysis in two Italian Research and Teaching Hospitals. Is the On-Site strategy effective? Ann. Ig. 2024, 36, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, P.M.; Scarioni, S.; Astorri, E.; Marrocu, C.; Tiwana, N.; Letzgus, M.; Borriello, C.; Castaldi, S. Vaccination Open Day: A Cross-Sectional Study on the 2023 Experience in Lombardy Region, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecce, M.; Perrone, P.M.; Castaldi, S. Tdap Booster Vaccination for Adults: Real-World Adherence to Current Recommendations in Italy and Evaluation of Two Alternative Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantoni, L.; Andreozzi, L.; Stera, G.; Toschi Vespasiani, G.; Biagi, C.; Zama, D.; Balduini, E.; Scheier, L.M.; Lanari, M. National survey conducted among Italian pediatricians examining the therapeutic management of croup. Respir. Med. 2024, 226, 107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapienza, M.; Furia, G.; La Regina, D.P.; Grimaldi, V.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Patrizi, C.; Capelli, G.; Rome OMCeO Group; Damiani, G. Primary care pediatricians and job satisfaction: A cross sectional study in the Lazio region. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2023, 49, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Phulgenda, S.; Antoniou, P.; Wong, D.L.F.; Iwamoto, K.; Kandelaki, K. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors on antimicrobial resistance among general public across 14 member states in the WHO European region: Results from a cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1274818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanyike, A.M.; Olum, R.; Kajjimu, J.; Owembabazi, S.; Ojilong, D.; Nassozi, D.R.; Amongin, J.F.; Atulinda, L.; Agaba, K.; Agira, D.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance and rational use of medicine: Knowledge, perceptions, and training of clinical health professions students in Uganda. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simegn, W.; Moges, G. Awareness and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance and factors associated with knowledge among adults in Dessie City, Northeast Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Chanvatik, S.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Kirivan, S.; Kaewkhankhaeng, W.; Thunyahan, A.; Lekagul, A. Population knowledge and awareness of antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance: Results from national household survey 2019 and changes from 2017. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, S.; Mora, L.; Fernandez, D.A.; Marín, A.; Berrío, I.; Mendoza-Charris, H.; Viana-Cárdenas, E.P.; Polo-Rodríguez, M.; Muñoz-Garcia, L.; Alvarez-Herrera, J.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior regarding antibiotics, antibiotic use, and antibiotic resistance in students and health care professionals of the district of Barranquilla (Colombia): A cross-sectional survey. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenzin, J.; Tshomo, K.P.; Wangda, S.; Gyeltshen, W.; Tshering, G. Knowledge, attitude and practice on antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance among competent persons in the community pharmacies in Bhutan. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 13239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahpawee, N.S.; Chaw, L.L.; Muharram, S.H.; Goh, H.P.; Hussain, Z.; Ming, L.C. University students’ antibiotic use and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance: What are the common myths? Antibiotics 2020, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sex | |

|---|---|

| F | 208 (82.2%) |

| M | 45 (17.8%) |

| Year of graduation | |

| 1960–1970 | 2 (0.8%) |

| 1971–1980 | 17 (6.7%) |

| 1981–1990 | 143 (56.5%) |

| 1991–2000 | 70 (27.7%) |

| 2001–2010 | 15 (5.9%) |

| 2011–2020 | 6 (2.4%) |

| Year of post-graduate specialization | |

| 1971–1980 | 3 (1.2%) |

| 1981–1990 | 81(32.0%) |

| 1991–2000 | 122 (48.2%) |

| 2001–2010 | 31 (12.3%) |

| 2011–2020 | 16 (6.3%) |

| Years spent working as a primary care pediatrician | |

| 1–5 years | 9 (3.6%) |

| 5–10 years | 12 (4.7%) |

| >10 years | 232 (91.7%) |

| Further specialization | |

| Yes | 38 (15.0%) |

| No | 215 (85.0%) |

| Participation in seminars and/or conferences on antimicrobial resistance | |

| No, and no interest in following them | 7 (2.8%) |

| No, but with interest in following them | 82 (32.3%) |

| Yes, but only 1 | 91 (36.0%) |

| Yes, and more than 1 | 73 (28.9%) |

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Knowledge gaps | |

| 0 | 194 (76.7%) |

| 1 | 59 (23.3%) |

| Legal repercussions | |

| 0 | 189 (74.7%) |

| 1 | 64 (25.3%) |

| Parental pressure | |

| 0 | 225 (88.9%) |

| 1 | 28 (11.1%) |

| Diagnostic uncertainty | |

| 0 | 170 (67.2%) |

| 1 | 83 (32.8%) |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Courses in the last 3 years (no, but I would like to follow them) | 0.243 | 0.04–1.31 | 0.1000 |

| Courses in the last 3 years (yes) | 0.210 | 0.04–1.09 | 0.0633 |

| Length of service (5–10 years) | 0.459 | 0.06–3.22 | 0.4330 |

| Length of service (>10 years) | 0.444 | 0.10–1.86 | 0.2670 |

| Sex (male) | 0.815 | 0.36–1.81 | 0.6150 |

| Diagnostic uncertainty (1) | 3.970 | 2.15–7.30 | 0.0001 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Courses in the last 3 years (no, but I would like to follow them) | 1.030 | 0.10–9.79 | 0.9760 |

| Courses in the last 3 years (yes) | 0.596 | 0.06–5.50 | 0.6480 |

| Years of working (5–10 years) | 0.759 | 0.08–7.03 | 0.8080 |

| Years of working (>10 years) | 0.464 | 0.08–2.46 | 0.3670 |

| Sex (male) | 0.887 | 0.30–2.59 | 0.8270 |

| Diagnostic uncertainty (1) | 2.310 | 1.03–5.22 | 0.0433 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perrone, P.M.; Picca, M.; Carrozzo, R.; Agostoni, C.V.; Marchisio, P.; Milani, G.P.; Castaldi, S. Factors behind Antibiotic Therapy: A Survey of Primary Care Pediatricians in Lombardy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081091

Perrone PM, Picca M, Carrozzo R, Agostoni CV, Marchisio P, Milani GP, Castaldi S. Factors behind Antibiotic Therapy: A Survey of Primary Care Pediatricians in Lombardy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(8):1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081091

Chicago/Turabian StylePerrone, Pier Mario, Marina Picca, Romeo Carrozzo, Carlo Virginio Agostoni, Paola Marchisio, Gregorio Paolo Milani, and Silvana Castaldi. 2024. "Factors behind Antibiotic Therapy: A Survey of Primary Care Pediatricians in Lombardy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 8: 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081091

APA StylePerrone, P. M., Picca, M., Carrozzo, R., Agostoni, C. V., Marchisio, P., Milani, G. P., & Castaldi, S. (2024). Factors behind Antibiotic Therapy: A Survey of Primary Care Pediatricians in Lombardy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081091