The Cross-Cultural Validation of Neuropsychological Assessments and Their Clinical Applications in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Scoping Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Studies involving the clinical assessment and diagnosis of cognitive functioning and cognitive change with respect to multiple languages and cultures, including both single and comparative case studies and more extensive sample size studies, for digital and non-digital neuropsychological assessments [14,15,16,24]. Theories related to cultural competence and neuropsychological assessments, such as those discussed in [25], support the need for culturally sensitive diagnostic practices. These models highlight how cultural factors influence cognitive assessment outcomes and stress the importance of adapting clinical practices to ensure validity across cultures.

- (2)

- Validation studies for adapting tools to language-specific or culture-specific assessments [13,14,19,20,25,26]. The need for cross-cultural validation is supported by theoretical models of test adaptation and equivalence, such as those proposed in [27]. These models provide a framework for understanding how psychological assessments need to be adapted and validated to maintain their reliability and validity across different cultural contexts.

- (3)

- Qualitative research on neuropsychological assessments, covering methods for cognitive function assessments, oral history or cultural memory for clinical condition evaluation, and intercultural research on the content and administration of cognitive tools in clinical research or everyday settings [11,15,16,17,28,29]. Theories from cultural psychology, such as those in [30,31], support the use of qualitative research to explore how culture shapes cognitive processes and behaviors, thus providing a theoretical basis for this category.

- (4)

- The development and design of cognitive function assessments and experimental procedures considering indigenous needs for medical resources [18,32]. The theoretical underpinnings of this category can be found in models of test construction and cultural adaptation, such as those discussed in [33] in the context of adapting educational and psychological tests. These models emphasize the importance of considering cultural differences in the development of assessment tools, ensuring that they are culturally relevant and valid for the populations being tested.

- (5)

- Theoretical papers and guidelines on the need to identify future directions and ethical considerations [21,34]. Theoretical discussions on ethics, such as those indicated in [35] on multicultural competence, provide a foundation for understanding the ethical challenges and considerations in applying neuropsychological assessments across different cultural groups.

- (6)

- Practice session papers, including studies reporting the development of digital app-based tools [22,36]. The integration of technology into neuropsychological assessments is supported by theoretical models of digital and remote assessments, such as those discussed in [37] that explored the implications of using digital tools in psychological testing. Theories related to the digital divide and accessibility, such as those presented in [38], also provide a framework for understanding the challenges and opportunities associated with implementing digital assessments in diverse cultural contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Importance of Cross-Cultural Validation

2.2. Cross-Cultural Considerations in Neuropsychological Assessments

2.3. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Principles and Applications

2.4. Fundamentals of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

2.5. Integration with Neuropsychological Assessments

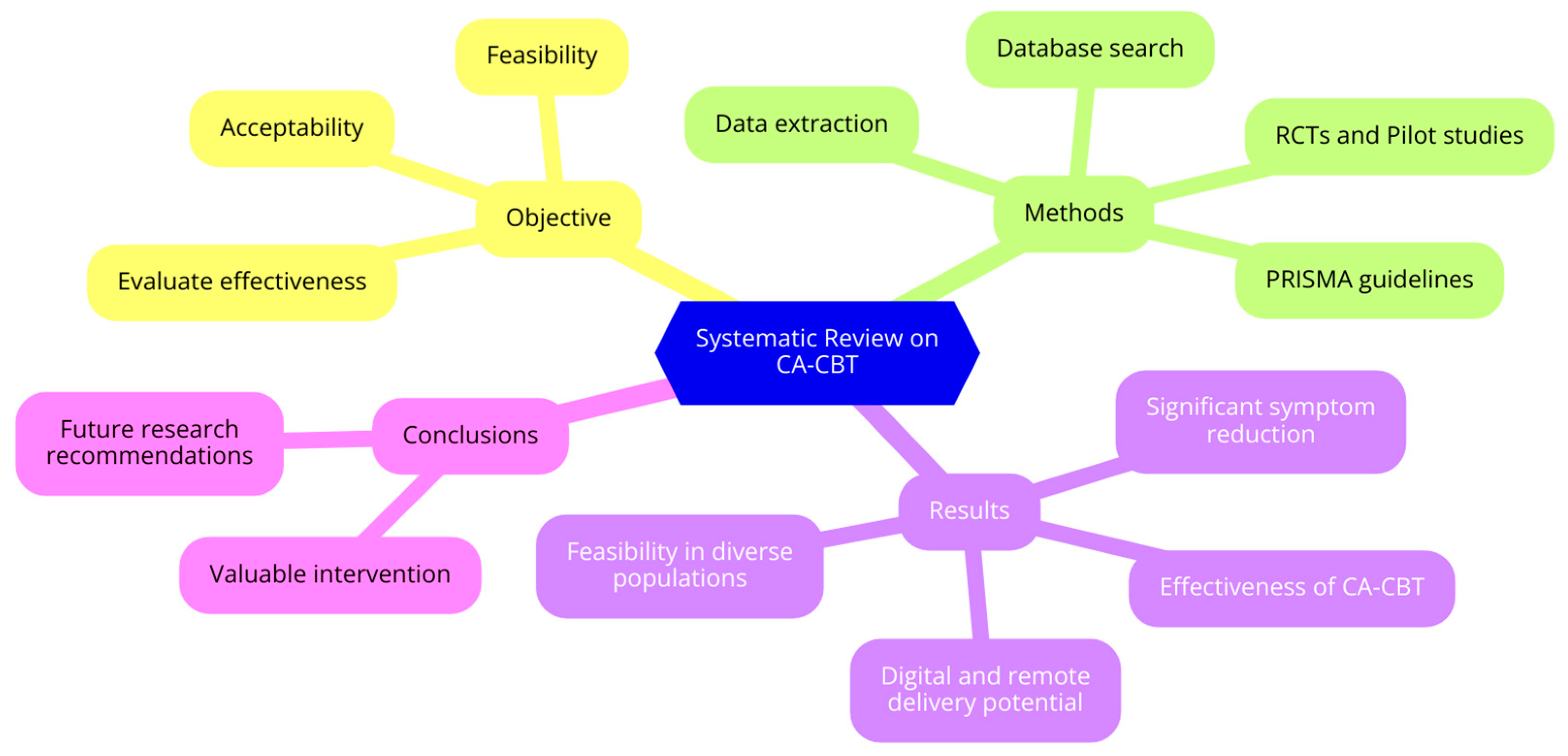

2.6. Scope and Objectives

2.7. Research Questions

- [RQ1] What are the long-term effects of CA-CBT on mental health outcomes across different cultural groups?

- [RQ2] What factors contribute to the success of CA-CBT, and how effective, feasible, and scalable are digital and remote CA-CBT platforms in diverse populations?

- [RQ3] What specific cultural adaptations are necessary for the effective implementation of CA-CBT in various cultural contexts?

- [RQ4] How does the effectiveness of CA-CBT compare to standard CBT and other therapeutic interventions in diverse populations?

- [RQ5] What are the key considerations in validating neuropsychological assessment tools for use in diverse cultural settings?

- [RQ6] How can neuropsychological assessments be adapted to better align with the cultural contexts of diverse populations receiving CBT?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

- “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy” OR “CBT”;

- “Culturally Adapted” OR “Cultural Adaptation” OR “Culturally Sensitive”;

- “Depression” OR “Anxiety” OR “PTSD” OR “Psychosis”;

- “Chinese Americans” OR “Latino” OR “Syrian Refugees” OR “Jordanian” OR “Malaysian” OR “Afghan Refugees” OR “Iraqi Women” OR “Japanese Children” OR “Tanzanian” OR “Kenyan”;

- “Randomized Controlled Trial” OR “RCT” OR “Pilot Study”.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4. Results

4.1. Effectiveness of Culturally Adapted CBT

4.2. Feasibility and Acceptability

4.3. Digital and Remote Interventions

4.4. Specific Populations and Settings

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilder, R.M.; Reise, S.P. Neuropsychological tests of the future: How do we get there from here? Clin. Neuropsychol. 2018, 33, 220–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, S.; Berg, E.v.D.; Goudsmit, M.; Jurgens, C.K.; van de Wiel, L.; Kalkisim, Y.; Uysal-Bozkir, Ö.; Ayhan, Y.; Nielsen, T.R.; Papma, J.M. A systematic review of neuropsychological tests for the assessment of dementia in non-western, low-educated or illiterate populations. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2019, 26, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkley, T.L.; Esopenko, C.; Zizak, V.; Bilder, R.M.; Strutt, A.M.; Tate, D.F.; Irimia, A. Challenges and opportunities for harmonization of cross-cultural neuropsychological data. Neuropsychology 2023, 37, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, T.R. Cognitive assessment in culturally, linguistically, and educationally diverse older populations in europe. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2022, 37, 153331752211170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, S.; Papma, J.M.; Berg, E.v.d.; Nielsen, T.R. Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in the european union: A delphi expert study. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 36, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, S.; European Consortium on Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology (ECCroN); Watermeyer, T.J.; Pomati, S.; Papma, J.M.; Nielsen, T.R.; Narme, P.; Mukadam, N.; Lozano-Ruiz, Á.; Ibanez-Casas, I.; et al. Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in europe: Position statement of the european consortium on cross-cultural neuropsychology (eccron). Clin. Neuropsychol. 2022, 36, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, A.; Farmakopoulou, I.; Dritsas, I.; Gkintoni, E. Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Anxiety Due to Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Cross-Sectional Trial in Adolescents. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardila, R.; Moreno, S. Cultural and linguistic differences in cognitive assessment: The importance of culturally sensitive neuropsychological tools. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli, M.; Ardila, A. Cultural and educational influences on neuropsychological test performance: A review. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrosky-Solís, F.; Ardila, A. Effects of bilingualism and cultural background on neuropsychological test results. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2004, 18, 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Manly, J.J.; Jacobs, D.M. Socioeconomic status, education, and cognitive aging among African Americans and whites. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Mindt, M.; Arentoft, A.; Kubo Germano, K. Challenges and strategies in assessing bilingual individuals. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2008, 22, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ardila, A.; Ramos, E. Bilingualism and cultural differences in neuropsychological assessments. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2010, 24, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brickman, A.M.; Cabo, R.; Manly, J.J. The role of cultural background and education in neuropsychological test performance among older adults. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2011, 25, 1275–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Arentoft, A.; Byrd, D.; Rivera Mindt, M. Neuropsychological assessment of culturally and linguistically diverse individuals. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2015, 29, 656–682. [Google Scholar]

- Suhr, J.A.; Anderson, S.L. The impact of cultural and language differences on neuropsychological test performance. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2017, 31, 1386–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, T.; Capetillo, D. Cultural competence in neuropsychological practice. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 34, 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Mindt, M.; Miranda, C.; Byrd, D. The influence of bilingualism and cultural background on neuropsychological test performance. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 35, 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Echemendia, R.J.; Harris, J.G.; Durand, T. Cultural and linguistic differences in cognitive assessments: A review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 35, 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Puente, A.E.; Ardila, A. Challenges in neuropsychological assessment of diverse populations. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2022, 36, 557–572. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Fletcher-Janzen, E. Advancements in culturally competent neuropsychological assessments. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 277–295. [Google Scholar]

- Mindt, M.R.; Arentoft, A. Effects of cultural and linguistic diversity on neuropsychological test outcomes. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2023, 37, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, L.A.; Brodale, D.L.; Elbulok-Charcape, M.M.; Barr, W.B. Challenges in the neuropsychological assessment of ethnic minorities. In Clinical Cultural Neuroscience: An Integrative Approach to Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology; Pedraza, O., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Dutt, A.; Fernández, A.L. The future of neuropsychology in a global context. In Understanding Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology; Fernández, A.L., Evans, J., Dutt, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, K.S. Current State of Practice: Variables to Consider when Norming Transgender Individuals in the Context of the Neuropsychological Assessment. In A Handbook of Geriatric Neuropsychology; Martin, T.A., Bush, S.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 342–368. [Google Scholar]

- Paltzer, J.Y.; Jo, M.Y. Cultural Considerations in Geriatric Neuropsychology. In A Handbook of Geriatric Neuropsychology, 2nd ed.; Bush, S.S., Martin, T.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 200–225. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver, F.J.; Leung, K. Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Terzulli, M.A. Neuropsychological Domains: Comparability in Construct Equivalence Across Test Batteries. 2020. Available online: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1141&context=theses_dissertations (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Baggett, N.; Lee, J.B. ACCEPTED ABSTRACTS for the American Academy of Pediatric Neuropsychology (AAPdN) Virtual Conference 2021. J. Pediatr. Neuropsychol. 2021, 7, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. Acts of Meaning; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Santos, M.; Anderson, K.; Miranda, M.; Wong, C.; Yañez, J.J.; Irani, F. Stepping into action: The role of neuropsychologists in social justice advocacy. In Cultural Diversity in Neuropsychological Assessment: Developing Understanding through Global Case Studies; Fernández, A.L., Evans, J., Dutt, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, R.K. Adaptation issues and methods for cross-cultural measurement. In Handbook of Multicultural Assessment: Clinical, Psychological, and Educational Applications; Matsumoto, D., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, A. Cultural Issues in Psychology: An Introduction to Global Discipline; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, D.W. Overcoming the five basic challenges in using multicultural organizational development as a diversity change strategy. Divers. Factor 2003, 11, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, A.; Evans, J.; Fernández, A.L. Challenges for neuropsychology in the global context. In Understanding Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology; Fernández, A.L., Evans, J., Dutt, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV), 4th ed.; NCS Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J. Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics 2006, 34, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.I.; Luck, L.; Jefferies, D.; Wilkes, L. Challenges in adapting a survey: Ensuring cross-cultural equivalence. Nurse Res. 2018, 26, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraev, E.B.; Levy, D.A. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Critical Thinking and Contemporary Applications; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Deffner, D.; Rohrer, J.M.; McElreath, R. A causal framework for cross-cultural generalizability. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 5, 25152459221106366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselica, A.M.; Karr, J.E.; Mikula, C.M.; Ranum, R.M.; Benge, J.F.; Medina, L.D.; Woods, S.P. Recent Advances in Neuropsychological Test Interpretation for Clinical Practice. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2024, 34, 637–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, M.; Zhu, X.; Lu, Y.Y.; Scheuer, L.S.; Passell, E.; Huang, G.C.; Germine, L.T.; Horowitz, T.S. How do we measure attention? Using factor analysis to establish construct validity of neuropsychological tests. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2021, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, M.; Jobst, L.J.; Zettler, I.; Hilbig, B.E.; Moshagen, M. Disentangling the effects of culture and language on measurement noninvariance in cross-cultural research: The culture, comprehension, and translation bias (CCT) procedure. Psychol. Assess. 2021, 33, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Jorgensen, N.A.; Telzer, E.H. A call for greater attention to culture in the study of brain and development. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lan, Y.J. Digital language learning (DLL): Insights from behavior, cognition, and the brain. In Bilingualism: Language and Cognition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hertrich, I.; Dietrich, S.; Ackermann, H. The margins of the language network in the brain. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 519955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, R.A.; Purzycki, B.G. Minds of gods and human cognitive constraints: Socio-ecological context shapes belief. In Religion and Its Evolution; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Peper, A. A general theory of consciousness I: Consciousness and adaptation. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2020, 13, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Álvarez, A.; Nielsen, T.R.; Delgado-Alonso, C.; Valles-Salgado, M.; López-Carbonero, J.I.; García-Ramos, R.; Gil-Moreno, M.J.; Díez-Cirarda, M.; Matias-Guiu, J.A. Validation of the European Cross-Cultural Neuropsychological Test Battery (CNTB) for the assessment of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1134111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario Nieves, E.; Rosenstein, L.D.; González, D.; Bordes Edgar, V.; Jofre Zarate, D.; MacDonald Wer, B. Is language translation enough in cross-cultural neuropsychological assessments of patients from Latin America? Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E.; Skokou, M.; Gourzis, P. Integrating Clinical Neuropsychology and Psychotic Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Analysis of Cognitive Dynamics, Interventions, and Underlying Mechanisms. Medicina 2024, 60, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.R.; Franzen, S.; Goudsmit, M.; Uysal-Bozkir, Ö. Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in the european context: Embracing maximum cultural diversity at minimal geographic distances. In Cultural Diversity in Neuropsychological Assessment; Fernández, A.L., Evans, J., Dutt, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A.L.; Evans, J. Cross-cultural testing: Adaptation, development, or cross-cultural tests? In Understanding Cross-Cultural Neuropsychology; Fernández, A.L., Evans, J., Dutt, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jawahiri, F.; Nielsen, T.R. Effects of acculturation on the cross-cultural neuropsychological test battery (CNTB) in a culturally and linguistically diverse population in Denmark. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 36, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasfous, A.F.; Daugherty, J.C. Cultural considerations in neuropsychological assessment of Arab populations. In Cultural Diversity in Neuropsychological Assessment; Fernández, A.L., Evans, J., Dutt, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hertenstein, E.; Trinca, E.; Wunderlin, M.; Schneider, C.L.; Züst, M.A.; Fehér, K.D.; Su, T.; Straten, A.V.; Berger, T.; Baglioni, C.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with mental disorders and comorbid insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 62, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, Y.J.; Sudhir, P.M.; Manjula, M.; Arumugham, S.S.; Narayanaswamy, J.C. Clinical practice guidelines for cognitive-behavioral therapies in anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62 (Suppl. S2), S230–S250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, N.; Shorer, S.; Shoval-Zuckerman, Y.; Freedman, S.; Monson, C.M.; Dekel, R. Treating posttraumatic stress disorder across cultures: A systematic review of cultural adaptations of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huey, S.J., Jr.; Park, A.L.; Galán, C.A.; Wang, C.X. Culturally responsive cognitive behavioral therapy for ethnically diverse populations. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 19, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Greenblatt, A.; Hu, R. A knowledge synthesis of cross-cultural psychotherapy research: A critical review. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2021, 52, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M.; Shirotsuki, K.; Sugaya, N. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for management of mental health and stress-related disorders: Recent advances in techniques and technologies. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2021, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Weingarden, H.; Ladis, I.; Braddick, V.; Shin, J.; Jacobson, N.C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in the digital age: Presidential address. Behav. Ther. 2020, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapoutot, M.; Peter-Derex, L.; Bastuji, H.; Leslie, W.; Schoendorff, B.; Heinzer, R.; Siclari, F.; Nicolas, A.; Lemoine, P.; Higgins, S.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for the discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepine use in insomnia and anxiety disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Orueta, U.; Rogers, B.M.; Blanco-Campal, A.; Burke, T. The challenge of neuropsychological assessment of visual/visuo-spatial memory: A critical, historical review, and lessons for the present and future. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 962025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.S.; Ingram, P.B.; Armistead-Jehle, P. Relationship of personality assessment inventory (PAI) over-reporting scales to performance validity testing in a military neuropsychological sample. Mil. Psychol. 2022, 34, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Brown, J.; Luchetti, M.; Aschwanden, D.; Stephan, Y.; Terracciano, A. Five-factor model personality traits and the trajectory of episodic memory: Individual-participant meta-analysis of 471,821 memory assessments from 120,640 participants. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2023, 78, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.R.; Quinn, D.K. Neuroimaging biomarkers of new-onset psychiatric disorders following traumatic brain injury. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risbrough, V.B.; Vaughn, M.N.; Friend, S.F. Role of inflammation in traumatic brain injury–associated risk for neuropsychiatric disorders: State of the evidence and where do we go from here. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Kourkoutas, E.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Mousi, M. Clinical Intervention Strategies and Family Dynamics in Adolescent Eating Disorders: A Scoping Review for Enhancing Early Detection and Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, J. The incremental value of neuropsychological assessment: A critical review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 34, 56–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.C. Culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy for Chinese Americans with depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskici, B. Culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy for Syrian refugee women in Turkey: A randomized controlled trial. J. Trauma. Stress 2021, 34, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damra, J. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy: Cultural adaptations for application in Jordanian culture. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1901–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kananian, S. Culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy plus problem management (CA-CBT+) with Afghan refugees: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Trauma. Stress 2020, 33, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemestani, M. A pilot randomized clinical trial of a novel, culturally adapted, trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral intervention for war-related PTSD in Iraqi women. J. Trauma. Stress 2022, 35, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhas, S. Adapting cognitive-behavioral therapy for a Malaysian Muslim. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, D. Culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT) for Latino women with treatment-resistant PTSD: A pilot study comparing CA-CBT to applied muscle relaxation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca-Sanabria, A. Assessing the efficacy of a culturally adapted cognitive behavioral internet-delivered treatment for depression: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, M. Culturally adapted, web-based cognitive behavioral therapy for Spanish-speaking individuals with substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2018, 94, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonyea, J.G. The effectiveness of a culturally sensitive cognitive behavioral group intervention for Latino Alzheimer’s caregivers. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, N. Preliminary evaluation of culturally adapted CBT for psychosis (CA-CBTp): Findings from developing culturally-sensitive CBT project (DCCP). Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2014, 42, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwight-Johnson, M. Telephone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for Latino patients living in rural areas: A randomized pilot study. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S. A randomized controlled trial of a bidirectional cultural adaptation of cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Jaeger, B. The art and skill of delivering culturally responsive trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy in Tanzania and Kenya. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2017, 9, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palic, S. An explorative outcome study of CBT-based multidisciplinary treatment in a diverse group of refugees from a Danish treatment centre for rehabilitation of traumatized refugees. Torture 2009, 19, 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stange, J.P. Brain-behavioral adaptability predicts response to cognitive behavioral therapy for emotional disorders: A person-centered event-related potential study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, N. Pilot randomized controlled trial of culturally adapted cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis (CaCBTp) in Pakistan. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 190, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Kourkoutas, E.; Yotsidi, V.; Stavrou, P.D.; Prinianaki, D. Clinical Efficacy of Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño, E.M.; Arce Rentería, M.; Gross, A.L.; Jones, R.N.; Gonzalez, C.; Wong, R.; Weir, D.R.; Langa, K.M.; Manly, J.J. A cultural neuropsychological approach to harmonization of cognitive data across culturally and linguistically diverse older adult populations. Neuropsychology 2023, 37, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.L.; Li, C.; Briceño, E.M.; Rentería, M.A.; Jones, R.N.; Langa, K.M.; Manly, J.J.; Nichols, E.; Weir, D.; Wong, R.; et al. Harmonization of later-life cognitive function across national contexts: Results from the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocols. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023, 4, e573–e583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, F.; Su, C.; Du, W.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Su, W.; et al. A comparison of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, N.; Hashem, R.; Gad, M.; Brown, A.; Levis, B.; Renoux, C.; Thombs, B.D.; McInnes, M.D. Accuracy of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Tool for detecting mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 3235–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E. Clinical neuropsychological characteristics of bipolar disorder, with a focus on cognitive and linguistic pattern: A conceptual analysis. F1000Research 2023, 12, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, B.; Agenagnew, L.; Workicho, A.; Abera, M. Psychometric properties of the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) to detect major neurocognitive disorder among older people in Ethiopia: A validation study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 18, 1789–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, H.; Chen, H. Assessing students’ translation competence: Integrating China’s standards of English with cognitive diagnostic assessment approaches. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 872025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningrum, S.E.; van Luijtelaar, G.; Sulastri, A. An online platform and a dynamic database for neuropsychological assessment in Indonesia. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2023, 30, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Year | Country/Culture | Neuropsychological Assessment | Sample Size | Validation Methodology | Key Findings | Application in CBT | Gaps/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hwang, 2015 [72] | USA/Chinese Americans | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | 50 | RCT | CA-CBT led to greater overall decrease in depressive symptoms | Enhanced effectiveness of CBT through cultural adaptation | Small sample size, short follow-up period, high initial severity of depression |

| Gonyea, 2016 [82] | USA/Latino | Neuropsychiatric Inventory, CES-D | 67 | RCT | Lower neuropsychiatric symptoms, less caregiver distress, greater self-efficacy | Culturally sensitive group CBT for caregivers | Limited to caregivers, short follow-up period |

| Habib, 2014 [83] | Pakistan | PANSS, PSYRATS, Insight Scale | 42 | RCT | Significant improvement in positive, negative, and overall psychotic symptoms | CA-CBT effective for psychosis in low-income settings | Small sample size, short follow-up period |

| Eskici, 2021 [73] | Turkish/Syrian Refugees | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 | 23 | RCT | Significant reduction in PTSD and anxious-depressive distress | CA-CBT effective for PTSD in refugee populations | Small sample size, short follow-up period |

| Damra, 2014 [74] | Jordan | PTSD and Depression Symptomatology | 18 | RCT | Significant post-treatment improvements in PTSD and depression symptoms | Feasibility and acceptability of TF-CBT in Jordanian culture | Small sample size, short follow-up period |

| Subhas, 2021 [77] | Malaysia/Muslim | Beck Anxiety Inventory | 1 | Single-case study | Significant reduction in anxiety and panic attack symptoms | Culturally and religiously adapted CBT for panic disorder | Single-case study, no control group |

| Dwight-Johnson, 2011 [84] | USA/Latino | Hopkins Symptom Checklist, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 | 101 | RCT | Significant improvement in depression outcomes | Feasibility and acceptability of telephone-based CBT | Small sample size, potential selection bias |

| Zemestani, 2022 [76] | Iraq | PTSD Symptom Severity, Depression, Anxiety, Stress | 48 | RCT | Significant reductions in PTSD, depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms | CA-TF-CBT effective for war-related PTSD | Short follow-up period |

| Kananian, 2020 [75] | German/Afghan Refugees | General Health Questionnaire, PTSD Checklist, Patient Health Questionnaire | 24 | RCT | Large improvements in general psychopathological distress and quality of life | CA-CBT+ effective for refugees, low dropout rate | Small sample size, short follow-up period |

| Hinton, 2011 [78] | USA/Latino | PTSD Symptom Scale, Anxiety Measures | 24 | RCT | Significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, large effect sizes | CA-CBT effective for treatment-resistant PTSD | Small sample size, short follow-up period |

| Ishikawa, 2019 [85] | Japan | Diagnostic Interview, Self-Report Measures of Anxiety and Depression | 51 | RCT | Significant improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms | Bidirectional cultural adaptation of CBT for children and adolescents | Short follow-up period |

| Salamanca-Sanabria, 2018 [79] | Colombia | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 | Not specified | RCT | Protocol for assessing efficacy of internet-delivered CBT | Methodology for culturally adapting internet-delivered interventions | No results reported, protocol study |

| Paris, 2018 [80] | USA/Spanish-speaking | Substance Use Frequency | 92 | RCT | Significant improvement in substance use outcomes | Web-based CBT effective for substance use disorders | Short follow-up period |

| Woods-Jaeger, 2017 [86] | Tanzania/Kenya | Qualitative Interviews | 12 | Qualitative Study | Importance of cultural responsiveness, value of TF-CBT for child mental health | Task-sharing approach for delivering TF-CBT | Small sample size, qualitative study |

| Palic, 2009 [87] | Denmark/Refugees | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, Trauma Symptom Checklist-23 | 26 | Observational Study | Small to medium effect sizes on most outcome measures | Multidisciplinary treatment including CBT for traumatized refugees | Small sample size, observational study |

| Stange, 2017 [88] | USA | Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales | 39 | RCT | Greater brain-behavioral adaptability predicted better treatment response | Brain-behavioral adaptability as a predictor of CBT response | Small sample size, short follow-up period |

| Husain, 2017 [89] | Pakistan | PANSS, PSYRATS, Schedule for Assessment of Insight | 36 | RCT | Significant improvements in positive and negative symptoms and overall psychotic symptoms | Feasibility and acceptability of CA-CBT for psychosis | Small sample size, short follow-up period |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkintoni, E.; Nikolaou, G. The Cross-Cultural Validation of Neuropsychological Assessments and Their Clinical Applications in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Scoping Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081110

Gkintoni E, Nikolaou G. The Cross-Cultural Validation of Neuropsychological Assessments and Their Clinical Applications in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Scoping Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(8):1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081110

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkintoni, Evgenia, and Georgios Nikolaou. 2024. "The Cross-Cultural Validation of Neuropsychological Assessments and Their Clinical Applications in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Scoping Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 8: 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081110

APA StyleGkintoni, E., & Nikolaou, G. (2024). The Cross-Cultural Validation of Neuropsychological Assessments and Their Clinical Applications in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Scoping Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21081110