Start of the Season in a Seasonal Work Context: A Better Understanding of the Difficulties Experienced by Seasonal Workers in the Food Processing Industry for the Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

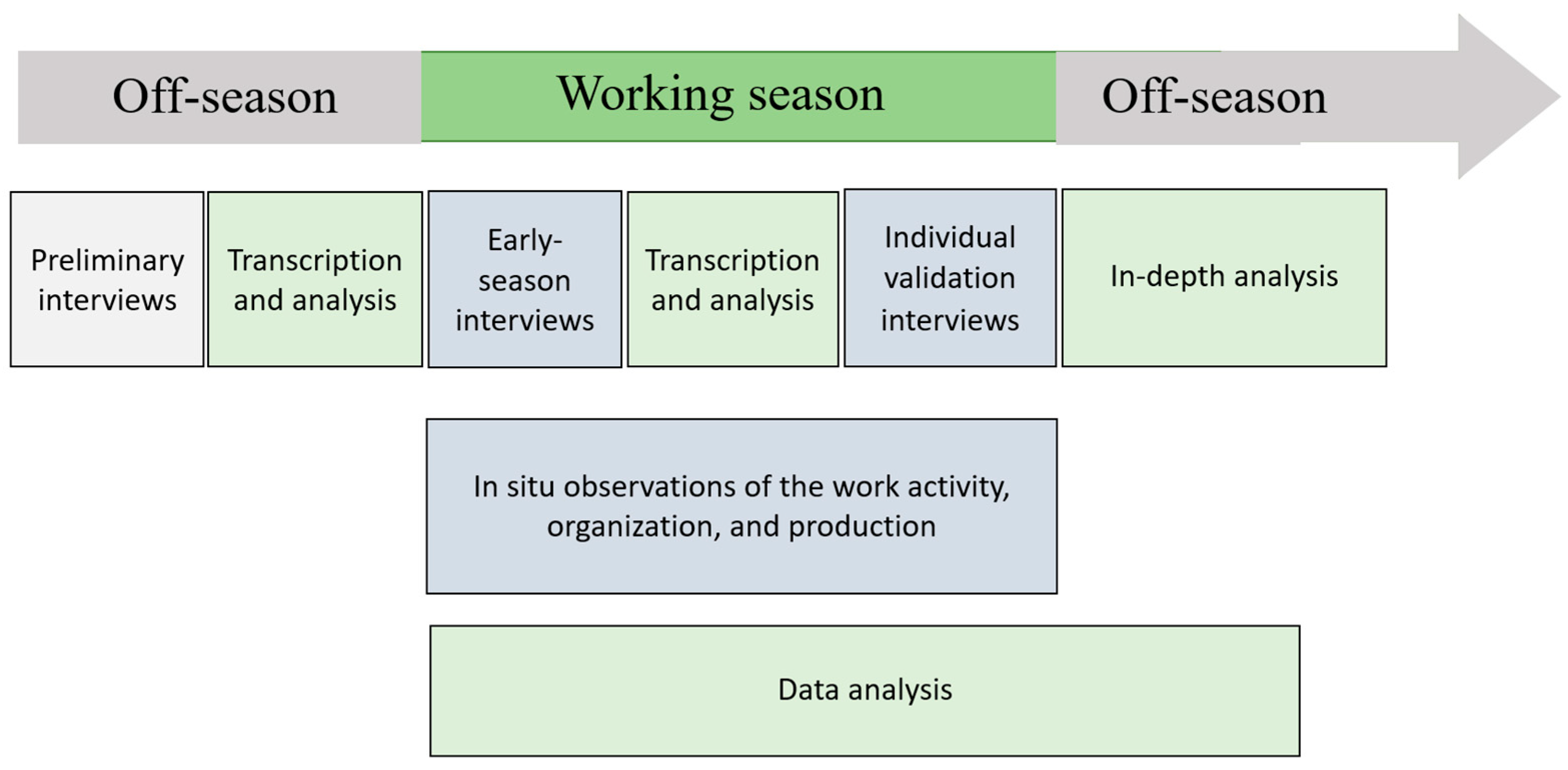

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Methods and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

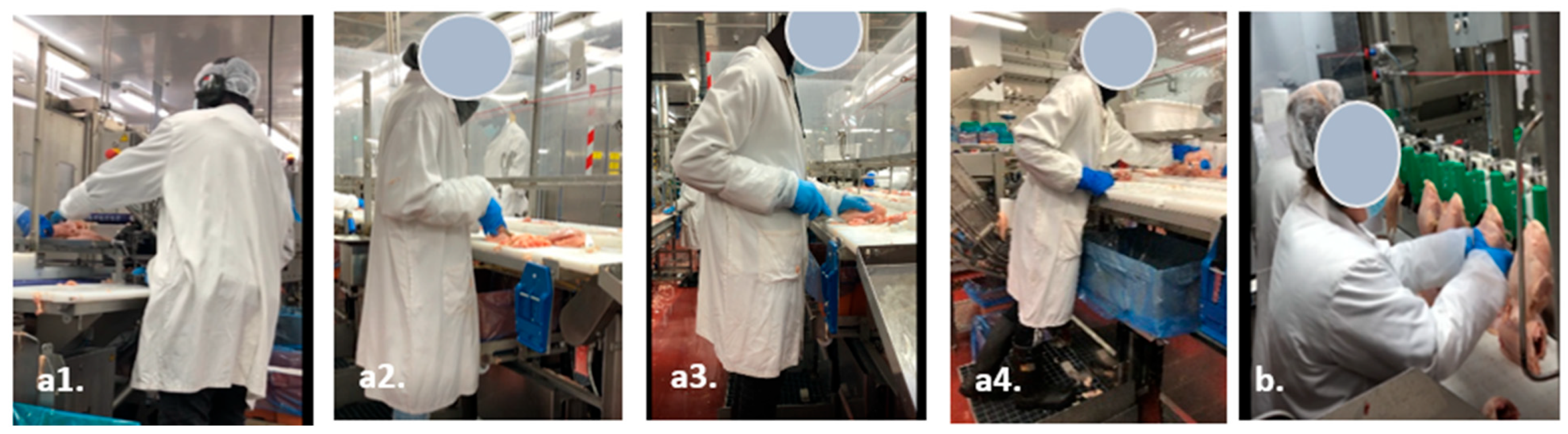

3.1. Working Conditions

3.2. Difficulties Encountered by Seasonal Workers at the Start of the Season and Determinants

3.2.1. Significant Physical Strain as Soon as the Season Begins

“The hooks go fast, you can’t miss your movement, you have to be just as fast, (…) keep up with the rhythm. This is a problem because it’s often this speed that also causes pain. When it goes fast, you feel like it’s going to be really difficult (Verbatim extracts from examples of participant difficulties. The extracts are a free translation from the original French transcripts.).”[T1, returning seasonal worker]

“[When there are many chicken breasts], you’re going to try to grab them, but anyway, they keep going, they keep going, you catch one, you catch one, but then you miss one. You’re not going to be able to get all of them.”[T6, new seasonal worker]

“On the second [day of the season] I was on the [production] line all day, (…) the repeated movements hurt. So my wrists and my arms, they hurt, (…) making it a little harder to keep up with the work.”[T8, new seasonal worker]

3.2.2. Quickly Learning/Relearning Practical and Preventive Skills

“When I went back to work at the start of the season, it had been a long time since I’d worked, and it felt like the line was moving even faster. It doesn’t make sense how fast it goes. There’s no time at all to take a break. (…) [You] have to go faster and faster. It’s like we are always worried, “is that how you do it, am I missing something?” ”[T2, returning seasonal worker]

“It’s very much an abrupt return to work. It’s like I’d lost the habit of doing the movements I’d done every day, which meant I had to go from never doing that to doing it all day long, which means that… in the beginning [of the season], it was definitely rough … for my injuries. At the beginning [of the season], it was like I was a bit lost. It just went a little too fast.”[T2, returning seasonal worker]

“They tell you only the essential. You have to remove all the bones. They won’t show you how to remove the bone. You have to figure it out and cut.”[T7, new seasonal worker]

“They didn’t really show us how to hang the chicken. There is a specific way to do it so you don’t hurt your arms. And I didn’t know this, as I ended up hurting myself, it hurt at the end of the day. And it went so fast…. For the first time on the line, you feel a bit lost because it’s going too fast. (…) You don’t understand why you’re doing it so badly, while the others beside you find it super easy.”[T8, new seasonal worker]

3.2.3. Rapid Adjustment to Working Complexity: A Non-Negligible Cognitive Activity

“When you come back [at work], how your memory gets working, I did that, and then at the beginning, I felt that it was more difficult to learn again…. When I start working again at the beginning, I have the sense that it feels somewhat different. It changes depending on the products. With the rounds [chicken pieces], there was a lot more to do. For the rounds [chicken pieces], you had to make them flat [lying flat in the bag]. And then get rid of some of the air that was inside the bag so it wouldn’t cause a problem. And then to see if the box had no defects. The movement to place the rounds, that [also] varied.”[T1, returning seasonal worker]

“Mostly, you have the pedal, that means that you’re hanging like everyone else, except you also have to watch the pedal down below, which is what opens the door to let the chickens slide down and come onto the belt [the conveyor]. (…) You can’t ever not have chickens in front of you [the conveyor]. Sometimes you hit the pedal while forgetting about the other thing or you do the other thing [hang the chicken on the hook] while forgetting the pedal. Sometimes, there aren’t any chickens and the others are like, “come on, send the chickens”[T6, new seasonal worker]

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Govaerts, R.; Tassignon, B.; Ghillebert, J.; Serrien, B.; De Bock, S.; Ampe, T.; El Makrini, I.; Vanderborght, B.; Meeusen, R.; De Pauw, K. Prevalence and incidence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in secondary industries of 21st century Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, D.S. Development and Validation of a Proactive Ergonomics Intervention Targeting Seasonal Agricultural Workers. Master’s Thesis, Lethbridge University, Lethbridge, AB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schweder, P.; Quinlan, M.; Bohle, P.; Lamm, F.; Bin Ang, A.H. Injury rates and psychological wellbeing in temporary work: A study of seasonal workers in the New Zealand food processing industry. N. Z. J. Employ. Relat. 2015, 40, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Major, M.E.; Wild, P.; Clabault, H. Travail Saisonnier et Santé au Travail: Bilan des Connaissances et Développement D’une Méthode D’analyse pour le suivi Longitudinal des Troubles Musculosquelettiques. 2020. Available online: https://www.irsst.qc.ca/publications-et-outils/publication-irsst/i/101081/n/travail-saisonnier-et-sante-au-travail (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Gouvernement du Canada. Permanence de L’emploi (Permanent Et temporaire) Selon L’industrie, Données Annuelles. 2018. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/fr/tv.action?pid=1410007201 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Gouvernement du Canada. Groupes D’industries Selon la Catégorie de Travailleur Incluant la Permanence de L’emploi, la Situation D’activité, L’âge et le Genre: Canada, Provinces et Territoires, Régions Métropolitaines de Recensement et Agglomérations de Recensement y Compris les Parties. 2022. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/fr/tv.action?pid=9810044801 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Houshyar, E.; Kim, I.J. Understanding musculoskeletal disorders among Iranian apple harvesting laborers: Ergonomic and stop watch time studies. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 67, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbeau, D.; Dubé, P.A.; Dubeau, D.; LeBel, L. Les Effets d’un Entraînement Physique Pré-Saison sur le Travail et la Sécurité des Débroussailleurs—Étude de Faisabilité D’une Approche de Mesure. 2010. Available online: https://www.irsst.qc.ca/media/documents/PubIRSST/R-664.pdf?v=2023-04-26 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Major, M.E.; Vézina, N. The Organization of Working Time: Developing an Understanding and Action Plan to Promote Workers’ Health in a Seasonal Work Context. New Solut. 2017, 27, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappin, D.C.; Bentley, T.A.; Vitalis, A. The role of contextual factors for musculoskeletal disorders in the New Zealand meat processing industry. Ergonomics 2008, 51, 1576–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.E.; Vézina, N. Pour une prévention durable des troubles musculosquelettiques chez des travailleuses saisonnières: Prise en compte du travail réel. Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la santé 2016, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, B.; Jaindl, B.; Dykes, L.; Coulthard, J.; Naylen, J.; Rocheleau, N.; Clay, L.; Khan, M.I.; Trask, C. Get ’Er Done: Experiences of Canadian Farmers Living with Chronic Low Back Disorders. Physiother. Can. 2019, 71, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.E.; Clabault, H.; Goupil, A. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Interventions in a Seasonal Work Context: A Scoping Review of Sex and Gender Considerations. In Proceedings of the 21st Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2021); Black, N.L., Neumann, W.P., Noy, I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.E.; Wild, P.; Clabault, H. Développement méthodologique: Indicateurs et profils pour le suivi longitudinal des troubles musculo-squelettiques liés au travail. Perspectives Interdisciplinaires Travail Santé (PISTES) 2022, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, H.J.; Loomis, D.; Anne McDonald, M.; Kucera, K.; Marshall, S.; Li, L. Musculoskeletal symptoms among commercial fishers in North Carolina. Appl. Ergon. 2004, 35, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweder, P. Occupational Health and Safety of Seasonal Workers in Agricultural Processing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mimeault, I.; Simard, M. Exclusions légales et sociales des travailleurs agricoles saisonniers véhiculés quotidiennement au Québec. Ind. Relations. 1999, 54, 388–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M.; Northcraft-Baxter, L.; Escoffery, C.; Greene, B.L. Musculoskeletal health in South Georgia farmworkers: A mixed methods study. Work 2012, 43, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, F.; Laville, A.; Daniellou, F.; Duraffourg, J.; Kerguelen, A. Understanding and Transforming Work: The Pratice of Ergonomics; Éditions ANACT: Lyon, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- St-Vincent, M.; Vézina, N.; Bellemare, M.; Denis, D.; Ledoux, E.; Imbeau, D. L’intervention en Ergonomie; Éditions MultiMondes: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, Y.C. L’étude de Cas Comme Méthode de Recherche, 2nd ed.; Presses de l’Université du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, M.F.; Gagnon, J. Fondements et Étapes du Processus de Recherche: Méthodes Quantitatives et Qualitatives, 3rd ed.; Chenelière Éducation: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Scolarité des Travailleurs du Secteur Agroalimentaire Âgés de 15 ans ou Plus, Selon la PLOP, Sept Régions Agricoles du Québec, 2011. 2017. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/2017004/tbl/tbl_15-fra.htm (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Statistics Canada. Portrait des Travailleurs de la Langue Française Dans les Industries Agricole et Agroalimentaire des Provinces de L’atlantique, 2006-2016. 2021. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2021003-fra.htm (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Act respecting Labour Standards, RSQ ch N-1.1: Division VI.2, act 84.3. 2023. Available online: https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cs/n-1.1#se:84_3 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Act respecting Labour Standards, RSQ ch N-1-1: Division VI.2, act 84.2. 2023. Available online: https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cs/n-1.1#se:84_2 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Gauthier, B. Recherche Sociale: De la Problématique à la Collecte des Données; Presses de l’Université du Québec (PUQ): Québec, QC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Major, M.E.; Vézina, N. Analysis of worker strategies: A comprehensive understanding for the prevention of work related musculoskeletal disorders. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 48, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, K.; Vézina, N.; Major, M.-E.; Ouellet, S.; Tissot, F.; Couture, V.; Riel, J. Body maps: An indicator of physical pain for worker-oriented ergonomic interventions. Policy Pract. Health Saf. 2008, 6, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, N.; Ouellet, S.; Major, M.E. Quel schéma corporel pour la prévention des troubles musculo-squelettiques ? Corps 2009, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, N.; Stock, S.; Simard, M.; Saint-Jacques, Y.; Marchand, A.; Bilodeau, P.P.; Boucher, M.; Zaabat, S.; Campi, A. Problèmes Musculo-Squelettiques et Organisation Modulaire du Travail Dans une Usine de Fabrication de Bottes. 1998. Available online: https://www.irsst.qc.ca/media/documents/PubIRSST/R-199.pdf?v=2024-07-09 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Laperrière, E.; Ngomo, S.; Thibault, M.C.; Messing, K. Indicators for choosing an optimal mix of major working postures. Appl. Ergon. 2006, 37, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngomo, S.; Messing, K.; Perrault, H.; Comtois, A. Orthostatic symptoms, blood pressure and working postures of factory and service workers over an observed workday. Appl. Ergon. 2008, 39, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Analyse des Données Qualitatives; De Boeck Supérieur: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paillé, P.; Mucchielli, A. L’analyse Qualitative en Sciences Humaines et Sociales, 4th ed.; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roquelaure, Y. Promoting a Shared Representation of Workers’ Activities to Improve Integrated Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. Saf. Health Work. 2016, 7, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Lipscomb, H.J.; Casanova, V.; Neis, B.; Fraser, C.; Monaghan, P.; Vallejos, Q.M. Organization of work in the agricultural, forestry, and fishing sector in the US southeast: Implications for immigrant workers’ occupational safety and health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.E.; Clabault, H.; Wild, P. Interventions for the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders in a seasonal work context: A scoping review. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 94, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, T.R.; Dumas, G.A. Musculoskeletal symptoms in tree planters in Ontario, Canada. Work 2010, 36, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet, S.; Vézina, N. Savoirs professionnels et prévention des TMS: Portrait de leur transmission durant la formation et perspectives d’intervention. Perspectives Interdisciplinaires Travail Santé (PISTES) 2009, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutarel, F.; Caroly, S.; Vézina, N.; Daniellou, F. Marge de manœuvre situationnelle et pouvoir d’agir: Des concepts à l’intervention ergonomique. Le Trav. Hum. 2015, 78, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, F.; Lemarchand, C.; Hubault, F.; Brun, C.; Polin, A.; Faucheux, J.M. Troubles Musculosquelettiques et Travail: Quand la Santé Interroge L’organisation; ANACT: Lyon, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roquelaure, Y. Musculoskeletal Disorders and Psychosocial Factors at Work; ETUI aisbl; University of Angers: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Loisel, P.; Durand, M.J.; Berthelette, D.; Vézina, N.; Baril, R.; Gagnon, D.; Larivière, C.; Tremblay, C. Disability Prevention. Dis-M–nag. -Health-Outcomes 2001, 9, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisel, P.; Buchbinder, R.; Hazard, R.; Keller, R.; Scheel, I.; Van Tulder, M.; Webster, B. Prevention of Work Disability Due to Musculoskeletal Disorders: The Challenge of Implementing Evidence. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2005, 15, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norval, M.; Zare, M.; Brunet, R.; Coutarel, F.; Roquelaure, Y. Intérêt de la Marge de Manœuvre Situationnelle pour le ciblage des situations à risque de Troubles Musculo-Squelettiques. Activités 2019, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, E.; Beaugrand, S.; Jolly, C.; Ouellet, S.; Fournier, P.S. Les Conditions pour une Intégration Sécuritaire au Métier—Un Regard sur le Secteur Minier Québécois. 2015. Available online: https://www.irsst.qc.ca/publications-et-outils/publication/i/100852/n/integration-securitaire-mines (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Lieutaud, T. Besoins, intégration, conditions de travail des anesthésistes-réanimateurs remplaçants dans les centres hospitaliers généraux en région Rhône-Alpes. Ann. Françaises D’anesthésie Et De Réanimation 2013, 32, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampart, D. Le Travail Temporaire en Suisse (n0133). 2019. Available online: https://www.uss.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/Dossier/133F_JB-DL_Travail_temporaire_Version_francaise.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Major, M.E.; Feillou, I.; Roux, N.; Vézina, N. Facteurs Facilitants et défis liés à L’implantation d’une Intervention Visant la Prévention des Troubles Musculosquelettiques en Contexte de Travail Saisonnier: Une Étude Exploratoire dans le Secteur de la Transformation Alimentaire. 2024. Available online: https://www.irsst.qc.ca/recherche-sst/projets/projet/i/5698/n/facteurs-facilitants-et-defis-lies-a-l-implantation-d-une-intervention-visant-la-prevention-des-troubles-musculosquelettiques-en-contexte-de-travail-saisonnier-2019-0049 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Morisset, M.; Charron, I.; Turcotte, G.; Dostie, S. Chantier sur la Saisonnalité: Phase 2: Typologies de la Saisonnalité, Document de Travail pour Réflexion. 2012. Available online: https://cqrht.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Rapport_typologie_enjeux-solutions-2012.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

| Sex 1 | Age | First-Time Seasonal Worker | Returning Seasonal Worker | Years of Experience in the Plant (and in the Sector) | Start of Work Date | End of Work Date | Work Schedule | Workstations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging | Trimming | Cutting Table | Packing | Palletizing | Freezing | |||||||||

| T1 | M | 18 | X | 3 | 2 June 2021 | 6 August 2021 | 7:00 to 15:30 | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| T2 | M | 20 | X | 4 | 31 May 2021 | 20 August 2021 | 7:45 to 16:15 | X | X | X | ||||

| T3 | F | 20 | X | 1 | 23 June 2021 | 6 August 2021 | 7:45 to 16:15 | X | X | X | ||||

| T4 | M | 16 | X | 1 | 28 June 2021 | 19 August 2021 | 7:00 to 15:30 | X | X | |||||

| T5 | F | 16 | X | 0 | 28 June 2021 | 20 August 2021 | 16:00 to 00:00 | X | X | X | ||||

| T6 | M | 15 | X | 0 | 25 June 2021 | 20 August 2021 | 7:00 to 15:30 | X | X | X | ||||

| T7 | F | 28 | X | 0 | 21 June 2021 | 20 August 2021 | 16:00 to 00:00 | X | X | X | ||||

| T8 | F | 16 | X | 0 | 29 June 2021 | 20 August 2021 | 7:00 to 15:30 | X | X | X | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goupil, A.; Major, M.-E. Start of the Season in a Seasonal Work Context: A Better Understanding of the Difficulties Experienced by Seasonal Workers in the Food Processing Industry for the Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080997

Goupil A, Major M-E. Start of the Season in a Seasonal Work Context: A Better Understanding of the Difficulties Experienced by Seasonal Workers in the Food Processing Industry for the Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(8):997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080997

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoupil, Audrey, and Marie-Eve Major. 2024. "Start of the Season in a Seasonal Work Context: A Better Understanding of the Difficulties Experienced by Seasonal Workers in the Food Processing Industry for the Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 8: 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080997

APA StyleGoupil, A., & Major, M.-E. (2024). Start of the Season in a Seasonal Work Context: A Better Understanding of the Difficulties Experienced by Seasonal Workers in the Food Processing Industry for the Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080997