Religious Affiliation, Internalized Homonegativity and Depressive Symptoms: Unveiling Mental Health Inequalities among Brazilian Gay Men

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measurement Instruments

2.2. Procedures and Ethical Considerations

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Archibald, J.G.; Dunn, T. Sexual attitudes as predictors of homonegativity in college women. Ga. J. Coll. Stud. Aff. 2014, 30, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.G.; McLeod, L.D.; Morrison, M.A.; Anderson, D.; O’Connor, W.E. Gender stereotyping, homonegativity, and misconceptions about sexually coercive behavior among adolescents. Youth Soc. 1997, 28, 351–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, W.G.; da Silva, C.M.F.P. Homicídios da População de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis, Transexuais ou Transgêneros (LGBT) no Brasil: Uma Análise Espacial. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 1709–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério dos Direitos Humanos. Violência LGBTFóbicas no Brasil: Dados da Violência. 2018. Available online: https://prceu.usp.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/MDH_violencia_2018.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Parente, J.S.; Lira dos Santos, T.; Alencar, G.A. Violência física contra lésbicas, gays, bissexuais, travestis e transexuais no interior do nordeste brasileiro. Rev. Salud Publica 2018, 20, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, S.L.; Sareen, J. Sexual Orientation and its Relation to Mental Disorders and Suicide Attempts: Findings from a Nationally Representative Sample. Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatchel, T.; Merrin, G.J.; Espelage, D. Peer victimization and suicidality among LGBTQ youth: The roles of school belonging, self-compassion, and parental support. J. LGBT Youth. 2018, 16, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H.; Russell, S.T.; Hammack, P.L.; Frost, D.M.; Wilson, B.D.M. Minority stress, distress, and suicide attempts in three cohorts of sexual minority adults: A U.S. probability sample. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.d.S.O.; Junior, J.F.M.; Lima, A.I.B.; Eloi, J.F. Homonegatividade internalizada como um processo psicossocial: Contribuições a partir da psicologia histórico-cultural. Rev. Bras. Sex. Hum. 2022, 33, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, R.; Lopes, B.; Rehman, Z. A structural equation model for predicting depressive symptomatology in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic gay, lesbian and bisexual people in the UK. Psychol. Sex. 2019, 12, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakula, B.; Shoveller, J.; Ratner, P.A.; Carpiano, R. Prevalence and Co-Occurrence of Heavy Drinking and Anxiety and Mood Disorders Among Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Canadians. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.C.; Armelie, A.P.; Boarts, J.M.; Brazil, M.; Delahanty, D.L. PTSD, Depression, and Substance Use in Relation to Suicidality Risk among Traumatized Minority Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. Arch. Suicide Res. 2016, 20, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J.E.; Bränström, R. Hidden from happiness: Structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglass, R.P.; Conlin, S.E.; Duffy, R.D. Beyond Happiness: Minority Stress and Life Meaning Among LGB Individuals. J. Homosex. 2019, 67, 1587–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.; Pereira, H.; Alckmin-Carvalho, F. Occupational Health, Psychosocial Risks and Prevention Factors in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and Other Populations: A Narrative Review. Societies 2024, 14, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczynski, P.; Fasoli, F. Loneliness in sexual minority and heterosexual individuals: A comparative meta-analysis. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2022, 26, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, E.B.; Amorim, A.B.; Pereira, A.C.N. O entendimento do supremo tribunal federal à respeito da transfobia e Homonegatividade como racismo/The federal supreme court’s understanding regarding transphobia and homophobia as racism. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 118120–118150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, I. A Conquista do direito ao casamento LGBTI+: Da Assembleia Constituinte à Resolução do, C.N.J. Rev. Direito Práx. 2021, 12, 2490–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragusuku, H.A.; Lara, M.F.A. Uma análise histórica da resolução n 01/1999 do Conselho Federal de Psicologia: 20 anos de resistência à patologização da homossexualidade. Psicol. Ciênc. Prof. 2020, 39, e228652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alckmin-Carvalho, F.; Pereira, H.; Nichiata, L. “It’sa Lot of Closets to Come Out of in This Life”: Experiences of Brazilian Gay Men Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus at the Time of Diagnosis and Its Biopsychosocial Impacts. European Journal of Investigation in Health. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1068–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alckimin-Carvalho, F.; Chiapetti, N.; Nichiata, L.I. Homonegatividade internalizada e opressão social percebida por homens gays que vivem com hiv. Psicol. Saúde Debate 2023, 9, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, W. The development of an internalized homonegativity inventory for gay men. J. Homosex. 2001, 41, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meladze, P.; Brown, J. Religion, sexuality, and internalized homonegativity: Confronting cognitive dissonance in the Abrahamic religions. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, N.; Chang, S.R. Internalized homophobia, self-esteem, social support and depressive symptoms among sexual and gender minority women in Taiwan: An online survey. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.C.; Chang, C.C.; Chang, Y.P.; Chen, Y.L.; Yen, C.F. Associations among perceived sexual stigma from family and peers, internalized homonegativity, loneliness, depression, and anxiety among gay and bisexual men in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-González, M.; Gómez, F.; Bahamondes, J.; Barrientos, J.; Garrido-Rojas, L.; Espinoza-Tapia, R.; Casu, G. Internalized homonegativity moderates the association between attachment avoidance and emotional intimacy among same-sex male couples. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1148005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveltchuk, F.D.O.; Borsa, J.C. Homonegatividade internalizada, conectividad comunitaria y salud mental en una muestra de individuos LGB brasileños. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. 2019, 37, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Huang, Y.-T. “Strong Together”: Minority Stress, Internalized Homophobia, Relationship Satisfaction, and Depressive Symptoms among Taiwanese Young Gay Men. J. Sex Res. 2022, 59, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yolaç, E.; Meriç, M. Internalized homophobia and depression levels in LGBT individuals. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 57, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividade, M. Homossexualidade, gênero e cura em perspectivas pastorais evangélicas. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Soc. 2006, 61, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividade, M.; de Oliveira, L. Sexualidades ameaçadoras: Religião e Homonegatividade (s) em discursos evangélicos conservadores. Sex. Salud Soc.-Rev. Latinoam. 2009, 2, 121–161. Available online: https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/SexualidadSaludySociedad/article/view/32 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Natividade, M.; Oliveira, L. Diversidade sexual e religião: A construção de um problema. In As Novas Guerras Sexuais: Diferença, Poder Religioso e Identidades LGBT no Brasil; Natividade, M.T., Oliveira, L., Eds.; Garamond: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013; pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, F. Representações da homossexualidade no Espiritismo. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Soc. 2023, 38, e3811000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Características gerais da população, religião e pessoas com deficiência. 2010. Available online: http://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/94/cd_2010_religiao_deficiencia.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Boyon, N. LGBT+ Pride 2021 Global Survey. Institut Public de Sondage d’Opinion Secteur. 2021. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2021-06/LGBT%20Pride%202021%20Global%20Survey%20Report_3.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Cury, D.G.; de Sousa, A.A.; Vasconcelos, A.C.; Okubo, R.Y.; Fernandes, P.D. A influência da religião cristã na formação de posicionamentos referentes à homossexualidade. Perspect. Psicol. 2013, 17, 51–64. Available online: https://seer.ufu.br/index.php/perspectivasempsicologia/article/download/28039/15446/111012 (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Gomes, A.; Souza, L. Todo religioso é preconceituoso? Uma análise da influência da religiosidade no preconceito contra homossexuais. Psico 2021, 52, e36291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppana, S.; Gross, A.M. The impact of religiosity on the psychological well-being of LGBT Christians. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2019, 23, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.J.; Goldbach, J.T. Religious identity dissonance: Understanding how sexual minority adolescents manage antihomosexual religious messages. J. Homosex. 2021, 68, 2189–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietkiewicz, I.J.; Kołodziejczyk-Skrzypek, M. Living in sin? How gay Catholics manage their conflicting sexual and religious identities. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 1573–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowe, B.J.; Brown, J.; Taylor, A.J. Sex and the sinner: Comparing religious and nonreligious same-sex attracted adults on internalized homonegativity and distress. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, J.M.; Smolenski, D.J.; Brady, S.S.; Rosser, B.S. Religiosity, internalized homonegativity and outness in Christian men who have sex with men. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2012, 27, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.F. (Ed.) Sexo e Consciência; Editora Leal: Salvador, BA, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, Z.T.S.D.; Esperandio, M.R.G. Spirituality/religiosity of sexual and gender minorities in Brazil: Assessment of spiritual resources and religious struggles. Religions 2022, 13, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, J. A Frente Parlamentar Evangélica: Força política no estado laico brasileiro. Numen. Rev. Estud. Pesqui. Relig. 2013, 16, 29–57. Available online: https://periodicos.ufjf.br/index.php/numen/article/view/21884 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- De Mello Côrtes, A.; Gonçalves Buzolin, L. Paths Towards LGBT Rights Recognition in Brazil. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2024, 21, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.W.; Rosser, B.S. Measurement and correlates of internalized homophobia: A factor analytic study. J. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 52, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, A.N.; de Morais, N.A. Evidências de validade da escala de homofobia internalizada para gays e lésbicas brasileiros. Psico-USF 2019, 24, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenstein, C.; Andrade, L.H.S.G. Inventário de depressão de Beck: Propriedades psicométricas da versão em português. Rev. Psiquiatr. Clín. 1998, 25, 245–250. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/lil-228051#:~:text=A%20consistencia%20interna%20do%20BDI,panico%20e%20pacientes%20com%20depressao (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White Paper]. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Escher, C.; Gomez, R.; Paulraj, S.; Ma, F.; Spies-Upton, S.; Cummings, C.; Brown, L.M.; Thomas Tormala, T.; Goldblum, P. Relations of religion with depression and loneliness in older sexual and gender minority adults. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Carretta, R.F. Religious-based sexual stigma and psychological health: Roles of internalization, religious struggle, and religiosity. J. Homosex. 2020, 67, 1062–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M.; Zevulun, A. Mental health and coping patterns in Jewish gay men in Israel: The role of dual identity conflict, religious identity, and partnership status. J. Homosex. 2018, 65, 947–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, M.C.; Blosnich, J.R.; De Luca, S.M.; Brownson, C. Association of religiosity with sexual minority suicide ideation and attempt. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, D. Internalized Homophobia in Men: Wanting in the First Person Singular, Hating in the First Person Plural. Psychoanal. Q. 2002, 71, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Zheng, L. The Influence of Internalized Homophobia on Health-Related Quality of Life and Life Satisfaction Among Gay and Bisexual Men in China. Am. J. Men’s Health 2019, 13, 1557988319864775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 194) | Christians (n = 71) | Spiritualists (n = 52) | Atheists/ Agnostics (n = 71) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Marital status * | Single | 143 | 74.5 | 55 | 77.5 | 41 | 78.8 | 47 | 68.1 |

| Married | 43 | 22.4 | 13 | 18.3 | 11 | 21.2 | 19 | 27.5 | |

| Divorced | 6 | 3.1 | 3 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4.3 | |

| Skin color | White | 140 | 72.2 | 47 | 66.2 | 37 | 71.2 | 56 | 78.9 |

| Black or Brown | 54 | 27.8 | 24 | 33.8 | 15 | 28.8 | 15 | 21.1 | |

| Education | Elementary | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Middle/Secondary | 16 | 18.6 | 16 | 22.5 | 5 | 9.6 | 15 | 21.1 | |

| Technical | 33 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| College | 32 | 33 | 24 | 33.8 | 16 | 30.8 | 24 | 33.8 | |

| Postgraduate | 25 | 25.3 | 18 | 25.4 | 16 | 30.8 | 15 | 21.1 | |

| Master | 2 | 10.8 | 6 | 8.5 | 6 | 11.5 | 9 | 12.7 | |

| Doctorate | 4 | 9.8 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 13.5 | 7 | 9.9 | |

| Housing | Rented | 98 | 50.5 | 37 | 52.1 | 23 | 44.2 | 38 | 53.5 |

| Owned | 84 | 43.3 | 32 | 45.1 | 24 | 46.2 | 28 | 39.4 | |

| Borrowed/Lent | 12 | 6.2 | 2 | 2.8 | 5 | 9.6 | 5 | 7 | |

| Cohabitation | Alone | 70 | 36.1 | 29 | 40.8 | 22 | 42.3 | 19 | 26.8 |

| family/partner | 103 | 53.1 | 35 | 49.3 | 24 | 46.2 | 44 | 62 | |

| With colleagues/friends | 21 | 10.8 | 7 | 9.9 | 6 | 11.5 | 8 | 11.3 | |

| Socio-economic status ** | BRL 1300–1999 (EUR 234–EUR 360; USD 260–USD 400) | 12 | 6.8 | 7 | 10.3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6.8 |

| BRL 2000–4999 (EUR 360–EUR 900; USD 400–USD 1000) | 64 | 36.2 | 28 | 41.2 | 14 | 28 | 22 | 37.3 | |

| BRL 5000–9999 (EUR 900–EUR 1.800; USD 1000–USD 2000) | 44 | 24.9 | 11 | 16.2 | 16 | 32 | 17 | 28.8 | |

| BRL 10,000–14,999 (EUR 1800–EUR 2700; USD 2000–USD 3000) | 18 | 10.2 | 9 | 13.2 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 6.8 | |

| >BRL 15,000 (>EUR 2700; >USD 3000) | 39 | 22 | 13 | 19.1 | 14 | 28 | 12 | 20.3 | |

| Professional situation | Unemployed | 20 | 10.3 | 6 | 8.5 | 7 | 13.5 | 7 | 9.9 |

| Employed | 172 | 88.7 | 64 | 90.1 | 45 | 86.5 | 63 | 88.7 | |

| Retired | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Total Sample (n = 194) | Christians (n = 71) | Spiritualists (n = 52) | Atheists/ Agnostics (n = 71) | F(df) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 15.69 (9.36) | 15.9 (8.46) | 16.79 (9.93) | 14.66 (9.81) | 0.802 (2; 191) | 0.450 |

| Total homonegativity | 43.58 (6.92) | 45.77 (6.57) | 43.17 (7.69) | 41.68 (6.11) | 6.723 (2; 191) | 0.002 * |

| Internalized homonegativity | 30.71 (6.44) | 33.06 (6.13) | 30.35 (6.93) | 28.63 (5.63) | 9.212 (2; 191) | 0.000 ** |

| Social homonegativity | 12.87 (1.83) | 12.72 (1.77) | 12.83 (1.84) | 13.04 (1.87) | 0.570 (2; 191) | 0.567 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression | - | |||

| 2. Total homonegativity | 0.339 ** | - | ||

| 3. Internalized Homonegativity | 0.316 ** | 0.965 ** | - | |

| 4. Social Homonegativity | 0.170 * | 0.387 ** | 0.131 | - |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | |

| Age | −0.008 | 0.081 | −0.007 | 0.006 | 0.078 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.078 | 0.009 |

| Education | −1.000 | 0.465 | −0.160 * | −1.111 | 0.443 | −0.178 * | −1.135 | 0.446 | −0.181 * |

| Skin color | 1.480 | 1.511 | 0.071 | 0.593 | 1.448 | 0.028 | 0.664 | 1.457 | 0.032 |

| Marital Status | −2.714 | 1.335 | −0.151 * | −1.826 | 1.282 | −0.101 | −1.850 | 1.286 | −0.103 |

| Social Homophobia | 0.433 | 0.355 | 0.085 | 0.414 | 0.358 | 0.081 | |||

| Internalized Homophobia | 0.436 | 0.101 | 0.302 ** | 0.452 | 0.106 | 0.313 ** | |||

| Religion | 0.396 | 0.787 | 0.036 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.065 | 0.165 | 0.166 | ||||||

| F for change in R2 | 3.175 * | 5.994 ** | 5.153 ** | ||||||

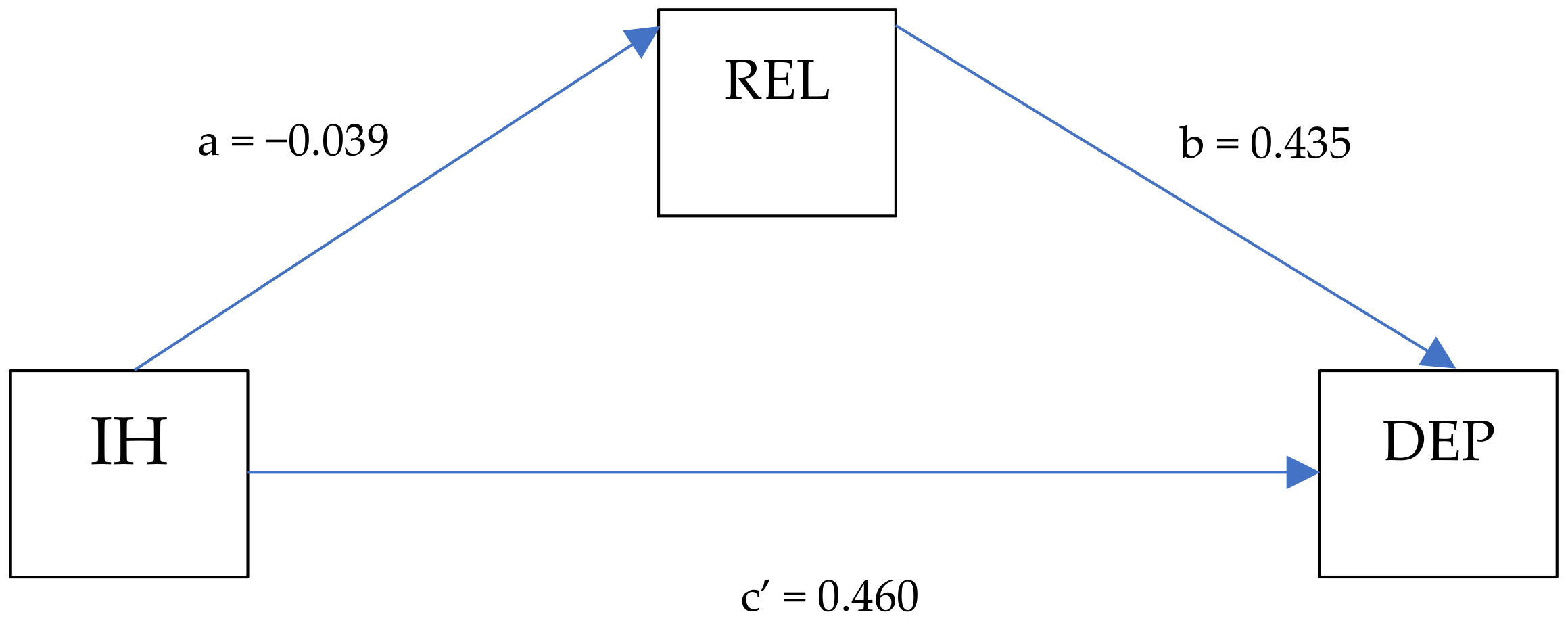

| Effect | Path | B | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | IH -> DEP | 0.460 | 0.099 | 0.263 | 0.656 | 4.616 | <0.001 |

| Indirect | IH -> REL -> DEP | −0.017 | 0.310 | −0.082 | 0.044 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alckmin-Carvalho, F.; Oliveira, A.; Silva, P.; Cruz, M.; Nichiata, L.; Pereira, H. Religious Affiliation, Internalized Homonegativity and Depressive Symptoms: Unveiling Mental Health Inequalities among Brazilian Gay Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091167

Alckmin-Carvalho F, Oliveira A, Silva P, Cruz M, Nichiata L, Pereira H. Religious Affiliation, Internalized Homonegativity and Depressive Symptoms: Unveiling Mental Health Inequalities among Brazilian Gay Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(9):1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091167

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlckmin-Carvalho, Felipe, António Oliveira, Patricia Silva, Madalena Cruz, Lúcia Nichiata, and Henrique Pereira. 2024. "Religious Affiliation, Internalized Homonegativity and Depressive Symptoms: Unveiling Mental Health Inequalities among Brazilian Gay Men" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 9: 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091167