The Relationship between Bicultural Acceptance Attitude and Self-Esteem among Multicultural Adolescents: The Mediating Effects of Parental Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection and Participants

2.3. Measurement of Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

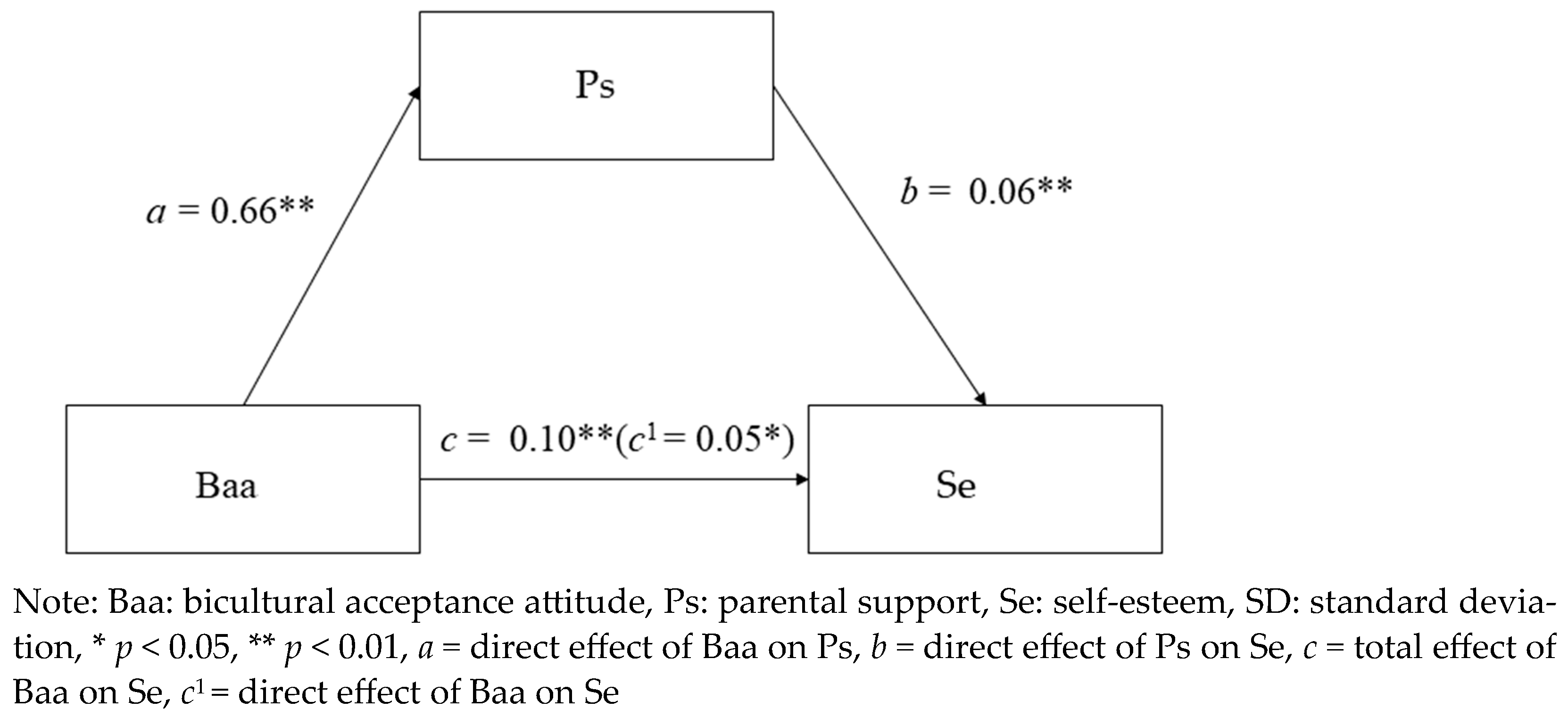

- -

- Total effect (c):

- -

- Relationship between independent variables and parameters (a):

- -

- Relationship between parameters and dependent variables (b):

- -

- Indirect effect (a × b):

- -

- Direct effect (c′):

2.5. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

3.3. Mediating Effect of Parental Support on Bicultural Acceptance Attitude and Self-Esteem

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghosh, R. Multiculturalism in a Comparative Perspective: Australia. Canada and India. Can. Ethn. Stud. 2018, 50, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Statistics Service. Statistics of Students from Multicultural Families; Ministry of Education: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Lundén, M.; Punamäki, R.L.; Silvén, M. Children’s psychological adjustment in dual- and single-ethnic families: Coregulation, socialization values, and emotion regulation in a 7-year follow-up study. Infant Child Dev. 2019, 28, e2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiClemente, R.J.; Hansen, W.B.; Ponton, L.E. Adolescents at risk. In Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.P.; Zhang, X.K. Understanding the relationship between self-esteem and creativity: A meta-analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 645–651. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.H. Structural relationships between the factors influencing academic achievement of multicultural students. Multicult. Educ. Stud. 2017, 10, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.J.; Roberts, R.E. Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2003, 9, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilgendahl, J.P.; Benet-Martinez, V.; Bishop, M.; Gilson, K.; Festa, L.; Levenson, C.; Rosenblum, R. So Now, I Wonder, What Am I?” A Narrative Approach to Bicultural Identity Integration. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 1596–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. A Study on the Development of Consultation Program for Multicultural Adolescent and Parents; Ministry of Gender Equality & Family: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2015.

- Nguyen, A.M.D.; Benet-Martínez, V. Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 44, 122–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.N.; Lai, M.H.; Wallen, J. Multiculturalism and subjective happiness as mediated by cultural and relational variables. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2009, 15, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkanopoulou, K.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C. Nostalgia and Biculturalism: How Host-Culture Nostalgia Fosters Bicultural Identity Integration. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2021, 52, 184191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, S.G.; Wei, M. Bicultural competence, acculturative family distancing, and future depression in Latino/a college students: A moderated mediation model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiaficas, D.; Suárez-Orozco, C.; Selcuk, R.S.; Taveeshi, G. Mediators of the relationship between acculturative stress and internalization symptoms for immigrant origin Youth. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2013, 19, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, S.; Dunn, E.; Lowery, B.S. The relationship between parental racial attitudes and children’s implicit prejudice. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 41, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.I. The Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction in the Relationship between Parenting Behavior and Multicultural Acceptance of Tardy Children in Multicultural Youth. Multicult. Child Youth Stud. 2021, 6, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wo, A.S.; Park, B.S. The Effect of Parenting Attitude on the Multicultural Expropriation of University Students According to Community Spirit. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Kahng, S.K. The Relationship among Acculturative Stress, Depression and Self-Esteem of multicultural adolesents Testing a Theoretical Model of the Stress Process. Ment. Health Soc. Work 2019, 47, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.H.; Yoon, H.M. The Effect of Acculturative Stress on Life Satisfaction of Adolescents with Multicultural Background in Mediation on Self-esteem: A Longitudinal Mediation Analysis Using Multivariate Latent Growth Curve Model. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2020, 27, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The effects of acculturative stress on school adjustment of multicultural adolescents mediated by depression and self-esteem. Youth Facil. Environ. 2019, 17, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- National Youth Policy Institute. Multicultural Adolescent Panel Survey (MAPS) 1st–8th Survey Data User Guide. 2021. Available online: https://www.nypi.re.kr/archive/mps (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Nho, C.R.; Hong, J.J. Adaptation of migrant workers’ children to Korean society: About Adaptation of Mongolian migrant workers’ children in Seoul, Gyeonggi Area. J. Korean Soc. Child Welf. 2006, 2, 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, U.; Park, Y. Psychological and behavioral pattern of Korean adolescents: With specific focus on the influence of friends, family, and school. Korean J. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 13, 99–142. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–mediator Variable Distinction on Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic and Statistical Consideration. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, M.D.; White, R.M.B.; Knight, G.P. A family stress model investigation of bicultural competence among U.S. Mexican-origin youth. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2021, 27, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.L.; Buckley, L.; Sheehan, M.; Shochet, I. School-based programs for increasing connectedness and reducing risk behavior: A systematic review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 25, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.A.; You, S.; Ha, D. Parental emotional support and adolescent happiness: Mediating roles of self-esteem and emotional intelligence. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2015, 10, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I.; Garcia, F.; Veiga, F.; Garcia, O.F.; Rodrigues, Y.; Serra, E. Parenting styles, internalization of values and self-esteem: A cross-cultural study in Spain, Portugal and Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.M. The relationship between social support and life satisfaction among Chinese and ethnic minority adolescents in Hong Kong. Mediat. Role Posit. Youth Dev. Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Cho, M.H.; Hong, H.Y. The influence of adolescents’ self-awareness on multicultural acceptability: The mediating effect of life satisfaction and sense of community. Korea Youth Res. Assoc. 2020, 27, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjew, A.M.; Koole, S.L. Terror Management in a Multicultural Society: Effects of Mortality Salience on Attitudes to Multiculturalism Are Moderated by National Identification and Self-Esteem Among Native Dutch People. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W.; Phinney, J.S.; Sam, D.L.; Vedder, P. Immigrant Youth: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaption. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2016, 55, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleque, A.; Uddin, K.; Aktar, R. Relations between Bicultural Attitudes, Paternal Versus Maternal Acceptance, and Psychological Adjustment of Ethnic Minority Youth in Bangladesh. J. Ethn. Cult. Stud. 2021, 8, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Tan, K.P.H.; Yasui, M.; Hahm, H.C. Advancing understanding of acculturation for adolescents of asian immigrants: Person-oriented analysis of acculturation strategy among Korean American youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1380–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, R.M. Linguistic acculturation and context on self-esteem: Hispanic youth between cultures. C A Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2011, 28, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.D. The Study on the Realities of Child Education in a Multicultural Family; Ministry of Education & Human Resources Development: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016.

- Sullivan, S.; Schwartz, S.J.; Prado, G.; Huang, S.; Pantin, H.; Szapocznik, J. A bidimensional model of acculturation for examining differences in family functioning and behavior problems in Hispanic immigrant adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2007, 27, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovey, J.D.; King, C.A. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1996, 35, 11831192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Bacallao, M.L. Acculturation, internalizing mental health symptoms, and self-esteem: Cultural experiences of Latino adolescents in North Carolina. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2007, 37, 273292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harker, K. Immigrant generation, assimilation, and adolescent psychological well-being. Soc. Forces 2001, 79, 9691004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, A.K.; Russell, S.T.; Crockett, L.J. Parenting styles and youth well-being across immigrant generations. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 185209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFromboise, T.; Coleman, H.L.; Gerton, J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 395412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, N.A.; Knight, G.P.; Morgan-Lopez, A.; Saenz, D.; Sirolli, A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In Latino Children and Families in the United States; Contreras, J.M., Kerns, K.A., Neal-Barnett, A.M., Eds.; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 2002; pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Anayeli, L.; Shen, C. Predictors of self-esteem among mexican immigrant adolescents: An examination of well-being through a biopsychosocial perspective. C A Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2021, 38, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, L.; Ittel, A.; Hoferichter, F.; Gallarin, M.M. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and adjustment among ethnically diverse college students: Family and peer support as protective factors. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2016, 57, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann-Stabile, C.; Gulbas, L.E. Latina adolescent suicide attempts: A review of familial, cultural, and community protective and risk factors. In Handbook of Youth Suicide Prevention: Integrating Research into Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 261–278. [Google Scholar]

| Category | N | % | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 587 | 49.00 | |

| Female | 610 | 51.00 | ||

| Age | 16 Years | 90 | 7.50 | |

| 17 Years | 1064 | 88.90 | ||

| 18 Years | 39 | 3.20 | ||

| 19 Years | 3 | 0.30 | ||

| 20 Years | 1 | 0.10 | ||

| Mother’s age | 47.53 ± 5.54 | |||

| Father’s age | 53.22 ± 4.59 | |||

| Mother’s education | ≤Middle school | 133 | 9.40 | |

| High school | 565 | 47.20 | ||

| University (two years) | 303 | 25.30 | ||

| University (four years) | 189 | 15.80 | ||

| Graduate school | 5 | 0.40 | ||

| Unknown | 22 | 1.90 | ||

| Father’s education | ≤Middle school | 360 | 30.10 | |

| High school | 594 | 49.60 | ||

| University (two years) | 70 | 5.90 | ||

| University (four years) | 113 | 9.50 | ||

| Graduate school | 10 | 0.80 | ||

| Unknown | 50 | 4.10 | ||

| Mother’s country of origin | Korea | 39 | 3.20 | |

| China (Han Chinese) | 84 | 7.10 | ||

| China (Korean Chinese) | 211 | 17.60 | ||

| Vietnam | 25 | 2.00 | ||

| The Philippines | 311 | 26.10 | ||

| Japan | 418 | 34.90 | ||

| Thailand | 49 | 4.10 | ||

| Others | 60 | 5.00 | ||

| Father’s country of origin | Korea | 1107 | 92.50 | |

| China (Han Chinese) | 2 | 0.20 | ||

| China (Korean Chinese) | 1 | 0.08 | ||

| Vietnam | 2 | 0.10 | ||

| The Philippines | 4 | 0.30 | ||

| Japan | 16 | 1.30 | ||

| Thailand | 1 | 0.08 | ||

| Others | 14 | 1.20 | ||

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | r (p) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baa | Ps | Se | ||||

| Baa | 2.92 ± 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 1 | — | — |

| Ps | 3.90 ± 0.71 | −0.037 | 0.07 | 0.438 ** | 1 | — |

| Se | 3.17 ± 0.34 | 0.3 8 | 2.58 | 0.144 ** | 0.179 ** | 1 |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Β | SE | t(p) | Adj. R2 | F(p) | Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β(p) | |||||||

| Baa | Se | 0.10 | 0.02 | 5.038 ** | 0.01998 | 25.38 ** | - |

| Baa | Ps | 0.66 | 0.039 | 16.88 ** | 0.1919 | 284.9 ** | - |

| Ps | Se | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.554 ** | 0.0359 | 23.27 ** | 0.05 ** |

| Baa | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.56 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Um, Y.-J. The Relationship between Bicultural Acceptance Attitude and Self-Esteem among Multicultural Adolescents: The Mediating Effects of Parental Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091175

Um Y-J. The Relationship between Bicultural Acceptance Attitude and Self-Esteem among Multicultural Adolescents: The Mediating Effects of Parental Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(9):1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091175

Chicago/Turabian StyleUm, Youn-Joo. 2024. "The Relationship between Bicultural Acceptance Attitude and Self-Esteem among Multicultural Adolescents: The Mediating Effects of Parental Support" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 9: 1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091175

APA StyleUm, Y.-J. (2024). The Relationship between Bicultural Acceptance Attitude and Self-Esteem among Multicultural Adolescents: The Mediating Effects of Parental Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(9), 1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091175