Developing a Safety Planning Smartphone App to Support Adolescents’ Self-Management During Emotional Crises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Phase 1: Qualitative Analysis

2.4. Phase 2: App Development

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Qualitative Analysis

3.1.1. General Information on Safety Planning

“In therapeutic settings, the patient’s survival is considered the primary objective and is therefore usually addressed first.”(Pr1)

“In the end, I’m the only one who more or less knows what’s on my safety plan.”(A1)

“The safety plan plays a big role for me, because I often find myself in situations where I’m not doing well. In those moments, I’m really glad to have something with me that can support me and help me to get through the situation.”(A6)

“Sometimes the [safety] plan doesn’t really help, for example when you are extremely angry.”(A1)

3.1.2. Content of the App

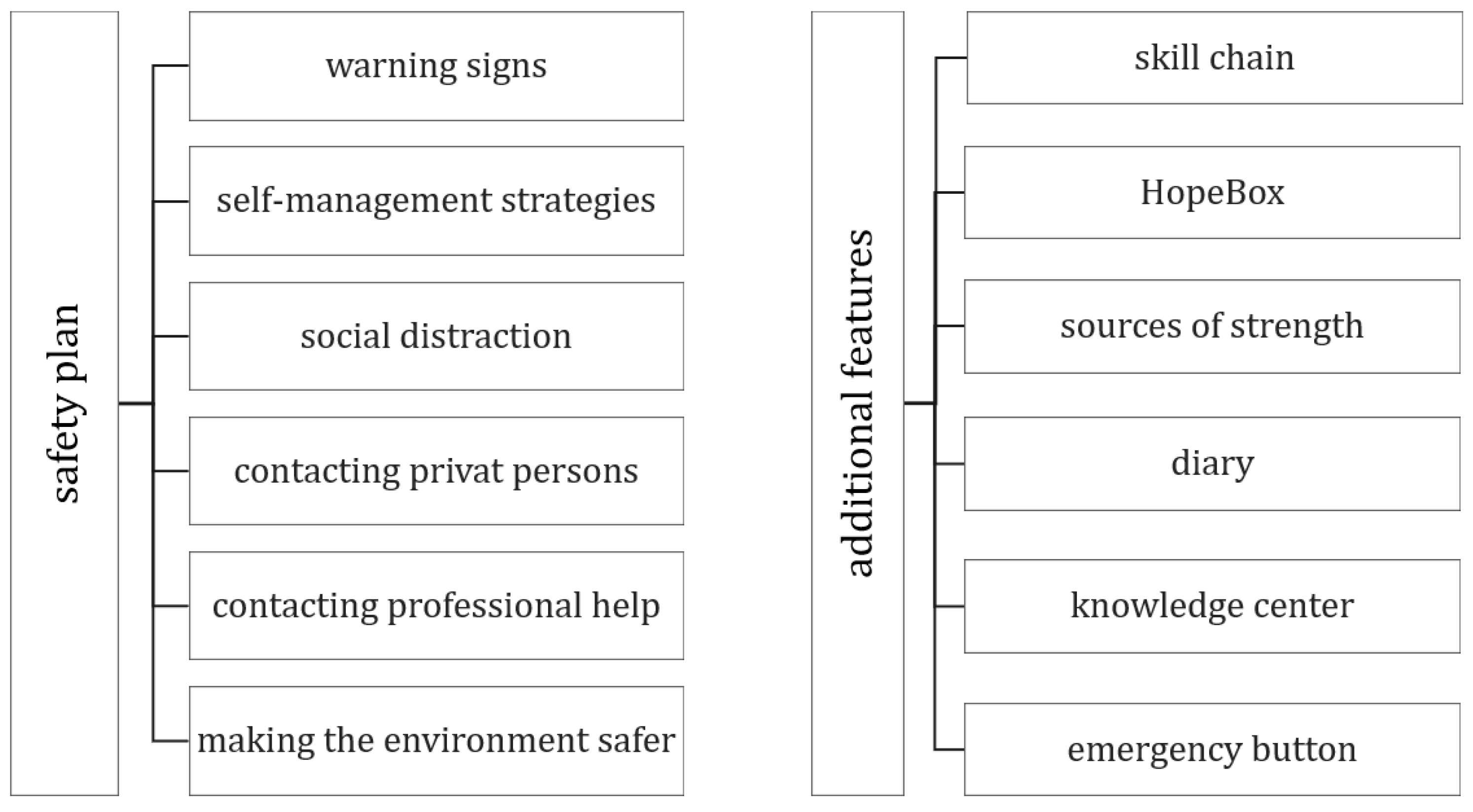

Safety Plan

Additional App Features

“I was thinking, like, when you’ve had a really good day, or seen something beautiful, like a sunset, it might be nice to save that in the app. Just as a way to store those moments, so when you’re feeling bad, you can remind yourself of the good things that have happened recently.”(A3)

3.1.3. App Settings

“I think for a lot of people, including myself, it would be really nice if the app checked in with you in the morning, just asking how you’re doing. It’s a good way to become more aware of how you’re actually feeling, like: am I doing okay right now, or do I need some support?”(A3)

3.1.4. Adjustability

“The ability to add new components, change or delete them, or even create entirely new ones. That kind of flexibility would be great. Just to have a bit more variety. Because if everything always stays exactly the same, I think, it gets boring for anyone.”(A1)

3.2. Phase 2: App Development

3.2.1. General Information on Safety Planning

3.2.2. Content

Safety Plan

Additional App Features

3.2.3. App Settings

3.2.4. Adjustability

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| app | application |

| CBPR | community-based participatory research |

| DBT | dialectical behavioral therapy |

| EMIRA | ecological momentary intervention to reduce suicide risk among adolescents |

| FG | focus group |

| SI | suicidal ideation |

| SPC | safety plan components |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

Appendix A

| Theme 1: Dealing with crises | |

|---|---|

| (1) All of you experienced crises, i.e., situations in which you were not feeling good. | |

| Identify helpful resources in crisis situations |

|

| Theme 2: Experiences with safety planning | |

| (2) I am sure you have all talked to your therapist about measures that can help you in a crisis situation. This often results in a whole list of things. | |

| Safety planning processes Identify people involved |

|

| (3) The purpose of a safety plan is to support you in a crisis. | |

| Positive/negative experiences with safety planning |

|

| Theme 3: Safety planning app | |

| (4) Nowadays, there is hardly anyone who doesn’t have a smartphone. We use it to buy a bus ticket, to stay in contact with our friends, to create a shopping list and much more. | |

| Cell phone use/app use General |

|

| (5) There are now numerous apps that can help with mental stress. | |

| Use of MH apps |

|

| (6) You already know that we want to develop an app that allows you to save and manage your safety plan on your smartphone. | |

| Evaluation of app-based safety planning |

|

| (7) I would now ask you to write down specifically which functions you would like to see in our app. Please take a new piece of paper for each function. | |

| Identify and evaluate functions |

|

Appendix B

| Theme 1: Crises of your child | |

|---|---|

| (1) Suicidal thoughts are unfortunately a common phenomenon among adolescents. All of you are parents of a child who has been in such a crisis situation. | |

| Identify helpful resources in crisis situations |

|

| Theme 2: Experiences with safety planning | |

| (2) Drawing up a safety plan is an important component in the treatment of adolescents at risk of suicide. Such a safety plan contains measures that, when applied in a crisis situation, can reduce the risk of suicidal behavior. | |

| Safety planning processes Identify people involved |

|

| (3) Safety plans should be used at the latest when adolescents find themselves in an emotional crisis situation and have suicidal thoughts. | |

| Positive/negative experiences with safety planning. Application barriers |

|

| Theme 3: Safety planning app | |

| (4) Nowadays, there is hardly anyone who doesn’t have a smartphone. Adolescents in particular are said to use their smartphone intensively. | |

| Smartphone use of the child |

|

| (5) There are now also numerous apps that can provide support in dealing with mental stress. | |

| Use of MH apps |

|

| (6) As you already know, we would like to develop an app in which adolescents can save and manage their safety plan. | |

| Evaluation of app-based safety planning |

|

Appendix C

| Theme 1: Experiences safety planning | |

|---|---|

| (1) They all have experience in treating adolescents who experience suicidal tendencies. Drawing up a safety plan is an important component of the treatment of adolescents at risk of suicide. | |

| Safety planning processes Identify people involved |

|

| (2) Safety plans should be used at the latest when adolescents are in an emotional crisis situation and have suicidal thoughts. | |

| Positive/negative experiences with safety planning; Application barriers |

|

| (3) Even if there are typical components of a safety plan, every safety plan is very personal and can be very individually designed. | |

| |

| Theme 2: Safety planning app | |

| (4) Nowadays, there is hardly anyone who doesn’t have a smartphone. We use it to buy a bus ticket, to stay in contact with our friends, to create a shopping list and much more. There are now also numerous apps that can help us deal with mental stress. They are also known as mental health apps. | |

| Use of MH apps |

|

| (5) As you already know, we would like to develop an app in which adolescents can save and manage their safety plan. | |

| Evaluation of app-based safety planning |

|

| (6) If possible, we would like to design the app so that it cannot only be used when needed, but also actively asks adolescents at regular intervals during the day how they are doing and reminds them of their safety plan. | |

| Evaluation of active app |

|

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2021: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Evans, E.; Hawton, K.; Rodham, K.; Deeks, J. The prevalence of suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2005, 35, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqueza, K.L.; Pagliaccio, D.; Durham, K.; Srinivasan, A.; Stewart, J.G.; Auerbach, R.P. Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients. Arch. Suicide Res. 2023, 27, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Saunders, K.E.A.; O’Connor, R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 2012, 379, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Destatis. Todesursachen Suizide; Destatis: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024.

- Plener, P.L.; Kaess, M. Suizidalität im Kindes- und Jugendalter. In Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie des Kindes- und Jugendalters; Fegert, J., Resch, F., Plener, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gili, M.; Castellví, P.; Vives, M.; de la Torre-Luque, A.; Almenara, J.; Blasco, M.J.; Cebrià, A.I.; Gabilondo, A.; Pérez-Ara, M.A.; A, M.-M.; et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people: A meta-analysis and systematic review of longitudinal studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, C.; Ollmann, T.M.; Miché, M.; Venz, J.; Hoyer, J.; Pieper, L.; Höfler, M.; Beesdo-Baum, K. Prevalence, Onset, and Course of Suicidal Behavior Among Adolescents and Young Adults in Germany. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1914386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K. Safety Planning Intervention: A Brief Intervention to Mitigate Suicide Risk. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K.; Brenner, L.A.; Galfalvy, H.C.; Currier, G.W.; Knox, K.L.; Chaudhury, S.R.; Bush, A.L.; Green, K.L. Comparison of the Safety Planning Intervention with Follow-up vs Usual Care of Suicidal Patients Treated in the Emergency Department. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuij, C.; van Ballegooijen, W.; de Beurs, D.; Juniar, D.; Erlangsen, A.; Portzky, G.; O’COnnor, R.C.; Smit, J.H.; Kerkhof, A.; Riper, H. Safety planning-type interventions for suicide prevention: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 219, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.; Rhodes, K.; Loughhead, M.; McIntyre, H.; Procter, N. The Effectiveness of the Safety Planning Intervention for Adults Experiencing Suicide-Related Distress: A Systematic Review. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022, 26, 1022–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott-Smith, S.; Ring, N.; Dougall, N.; Davey, J. Suicide prevention: What does the evidence show for the effectiveness of safety planning for children and young people?—A systematic scoping review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 30, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, A.M.; Al-Dajani, N.; Ballard, E.D.; Czyz, E. Safety plan use in the daily lives of adolescents after psychiatric hospitalization. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2023, 53, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Grady, C.; Melia, R.; Bogue, J.; O’Sullivan, M.; Young, K.; Duggan, J. A Mobile Health Approach for Improving Outcomes in Suicide Prevention (SafePlan). J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennard, B.D.; Biernesser, C.; Wolfe, K.L.; Foxwell, A.A.; Lee, S.J.C.; Rial, K.V.; Patel, S.; Cheng, C.; Goldstein, T.; McMakin, D.; et al. Developing a brief suicide prevention intervention and mobile phone application: A qualitative report. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2015, 33, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest. JIM 2022: Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-Jähriger in Deutschland; Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest: Stuttgart, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, J.M.; Sukhera, J.; Taylor-Gates, M. Integrating smartphone technology at the time of discharge from a child and adolescent inpatient psychiatry unit. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Myin-Germeys, I.; Klippel, A.; Steinhart, H.; Reininghaus, U. Ecological momentary interventions in psychiatry. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, N.E.; Dobscha, S.K.; Crumpton, R.; Denneson, L.M.; Hoffman, J.E.; Crain, A.; Cromer, R.; Kinn, J.T. A Virtual Hope Box smartphone app as an accessory to therapy: Proof-of-concept in a clinical sample of veterans. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2015, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denneson, L.M.; Smolenski, D.J.; Bauer, B.W.; Dobscha, S.K.; Bush, N.E. The Mediating Role of Coping Self-Efficacy in Hope Box Use and Suicidal Ideation Severity. Arch. Suicide Res. 2019, 23, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubad, M.; Elahi, F.; Marwaha, S. The Clinical Impacts of Mobile Mood-Monitoring in Young People with Mental Health Problems: The MeMO Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 687270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauwels, K.; Aerts, S.; Muijzers, E.; Jaegere Ede van Heeringen, K.; Portzky, G. BackUp: Development and evaluation of a smart-phone application for coping with suicidal crises. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovgaard Larsen, J.L.; Frandsen, H.; Erlangsen, A. MYPLAN—A Mobile Phone Application for Supporting People at Risk of Suicide. Crisis 2016, 37, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melvin, G.A.; Gresham, D.; Beaton, S.; Coles, J.; Tonge, B.J.; Gordon, M.S.; Stanley, B. Evaluating the feasibility and effectiveness of an Australian safety planning smartphone application: A pilot study within a tertiary mental health service. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, M.S.; Arendt, M.B.; Pedersen, C.M. Testing an App-Assisted Treatment for Suicide Prevention in a Randomized Controlled Trial: Effects on Suicide Risk and Depression. Behav. Ther. 2019, 50, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruen, A.J.; Wall, A.; Haines-Delmont, A.; Perkins, E. Exploring Suicidal Ideation Using an Innovative Mobile App-Strength Within Me: The Usability and Acceptability of Setting up a Trial Involving Mobile Technology and Mental Health Service Users. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e18407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.W.; Chang, H.J.; Kim, J.A. Development and Feasibility of a Safety Plan Mobile Application for Adolescent Suicide Attempt Survivors. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2020, 38, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras-Segovia, A.; De Granda-Beltrán, A.M.; Gallardo, C.; Abascal-Peiró, S.; Barrigón, M.L.; Artés-Rodríguez, A.; López-Castroman, J.; Courtet, P.; Baca-García, E. Smartphone-based safety plan for suicidal crisis: The SmartCrisis 2.0 pilot study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 169, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryglewicz, K.; Orr, V.L.; McNeil, M.J.; Taliaferro, L.A.; Hines, S.; Duffy, T.L.; Wisniewski, P.J. Translating Suicide Safety Planning Components into the Design of mHealth App Features: Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2024, 11, e52763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buus, N.; Juel, A.; Haskelberg, H.; Frandsen, H.; Larsen, J.L.S.; River, J.; Andreasson, K.; Nordentoft, M.; Davenport, T.; Erlangsen, A. User Involvement in Developing the MYPLAN Mobile Phone Safety Plan App for People in Suicidal Crisis: Case Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e11965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, L.; Gurtner, C.; Nuessli, S.; Miletic, M.; Bürkle, T.; Durrer, M. SERO—A New Mobile App for Suicide Prevention. Stud Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 292, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buus, N.; Erlangsen, A.; River, J.; Andreasson, K.; Frandsen, H.; Larsen, J.L.S.; Nordentoft, M.; Juel, A. Stakeholder Perspectives on Using and Developing the MYPLAN Suicide Prevention Mobile Phone Application: A Focus Group Study. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainbow, C.; Tatnell, R.; Blashki, G.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Melvin, G.A. Digital safety plan effectiveness and use: Findings from a three-month longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 333, 115748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, B.; Green, K.L.; Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M.; Brenner, L.A.; Brown, G.K. The construct and measurement of suicide-related coping. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 258, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, S.; Cheers, D.; Boydell, K.; Nguyen, Q.V.; Schubert, E.; Dunne, L.; Meade, T. Young People’s Response to Six Smartphone Apps for Anxiety and Depression: Focus Group Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e14385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høgsdal, H.; Kyrrestad, H.; Rye, M.; Kaiser, S. Exploring Adolescents’ Attitudes Toward Mental Health Apps: Concurrent Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e50222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Oetzel, J.G.; Minkler, M. (Eds.) Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer a Wiley Brand: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Qualitative Content Analysis: Methods, Practice and Software, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, M. User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development, 1st ed.; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, A.; Brown, G.K.; Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy for Suicidal Patients: Scientific and Clinical Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Le Jeannic, A.; Turmaine, K.; Gandré, C.; Vinet, M.-A.; Michel, M.; Chevreul, K. Defining the Characteristics of an e-Health Tool for Suicide Primary Prevention in the General Population: The StopBlues Case in France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuij, C.; van Ballegooijen, W.; de Beurs, D.; de Winter, R.F.P.; Gilissen, R.; O’cOnnor, R.C.; Smit, J.H.; Kerkhof, A.; Riper, H. The feasibility of using smartphone apps as treatment components for depressed suicidal outpatients. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 971046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupton, D. The digitally engaged patient: Self-monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Soc. Theory Health 2013, 11, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.; Awondo, P.; Miller, D. An Anthropological Approach to mHealth; UCL Press: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, M. Ageing with Smartphones in Urban Brazil: A Work in Progress; UCL Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Minich, M.; Moreno, M. Real-world adolescent smartphone use is associated with improvements in mood: An ecological momentary assessment study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, T.; Meigen, C.; Kiess, W.; Vogel, M. Smartphone use, wellbeing, and their association in children. Pediatr. Res. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacks, Y.; Weinstein, A.M. Excessive Smartphone Use Is Associated With Health Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 669042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.; Yuen, E.K.; Goetter, E.M.; Herbert, J.D.; Forman, E.M.; Acierno, R.; Ruggiero, K.J. mHealth: A mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective mental health care. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2014, 21, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, M.; Hildebrand, A.; Stemmler, M. Inanspruchnahme psychosozialer Hilfen bei jungen Erwachsenen mit suizidalem Erleben und Verhalten. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2024, 74, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwake, C. Akut-Inanspruchnahme von Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrischer Behandlung und ihre Veränderung in einem Zeitraum von fünf Jahren (2011–2015): Eine Retrospektive Querschnittsstudie in Einem Multizentrischen Deutschen Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrischen Patientenkollektiv; Medizinische Fakultät der Ruhr-Universität Bochum: Bochum, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Plener, P.L.; Groschwitz, R.C.; Franke, C.; Fegert, J.M.; Freyberger, H.J. Die stationäre psychiatrische Versorgung Adoleszenter in Deutschland. Z. Für Psychiatr. Psychol. Und Psychother. 2015, 63, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martínez, M.; Otero, A. Factors associated with cell phone use in adolescents in the community of Madrid (Spain). Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest. JIM-Studie 2024: Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-Jähriger: Mpfs; Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest: Stuttgart, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Fernandes, O. Problem mobile phone use in Spanish and British adolescents: First steps towards a cross-cultural research in Europe. In The Psychology of Social Networking; Riva, G., Wiederhold, B.K., Cipresso, P., Eds.; De Gruyter Open: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 186–201. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, R.; Upadhyay, R.; Jain, M. Prevalence of smart phone addiction, sleep quality and associated behaviour problems in adolescents. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adolescents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age (years) | sex | ICD-10 diagnosis | setting | |

| A1 | 17 | female | F3X | inpatient |

| A2 | 16 | female | F3X | inpatient |

| A3 | 15 | female | F5X | inpatient |

| A4 | 13 | female | unknown | inpatient |

| A5 | 17 | female | F6X | inpatient |

| A6 | 16 | female | F3X | inpatient |

| A7 | 16 | female | F6X | inpatient |

| Practitioners | ||||

| age (years) | sex | education | setting | |

| Pr1 | 43 | female | psychiatrist | outpatient |

| Pr2 | 30 | female | psychologist | inpatient |

| Pr3 | 36 | female | nurse | inpatient |

| Pr4 | 37 | female | psychiatrist | outpatient |

| Parents | ||||

| age (years) | sex | child died by suicide | child with SI during recruitment | |

| Pa1 | 52 | female | yes | no |

| Pa2 | 54 | female | no | yes |

| Pa3 | 57 | female | yes | yes |

| Pa4 | 50 | female | no | yes |

| Theme | Subtheme | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| General information on safety planning | “I’ve got a few things listed on it [my safety plan], and I keep adding things to it whenever I realize something else has helped me.” (A3) “If I know I’m working with a patient who might need something like this [a safety plan], I try to walk through a scenario with them, one where they’d actually have to use their safety plan. Then we think through the steps they could take to reduce the risk of anything serious happening. We start with the low-threshold options, the immediate surroundings, like: is there someone you can turn to? Or even first, what can you do to calm yourself down? Then we move on to involving other people, step by step, and if none of that works, we go all the way to the more serious actions, like calling the ambulance or the clinic.” (Pr1) | |

| Content of the app | Safety plan | “Just a suggestion [in the app] for something to help with distraction. Ideally, a tool offering a variety of options. Perhaps with the ability to add personal favorites that could then be integrated into the safety plan.” (A3) |

| Additional app features | “ (…) I also have to do this on the [clinic] ward: every evening I have to write down three positive things from the day.” (A5) | |

| App settings | “For example, receiving messages that pop up, such as ‘You’re amazing’.” (A6) | |

| Adjustability | “Well, if we’re in a good mood, it might be helpful to have the option to turn this feature off. Or at least, maybe having a button to disable notifications. (…) Because if it’s always on, it could potentially become annoying after a while (…) but that probably depends on the individual.” (A1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Großmann, T.; Hörger, J.; Bayer, N.; Bückle, S.; Buschek, D.; Fegert, J.M.; Laurenz, P.; Lühr, M.; Marek, F.; Rassenhofer, M.; et al. Developing a Safety Planning Smartphone App to Support Adolescents’ Self-Management During Emotional Crises. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111607

Großmann T, Hörger J, Bayer N, Bückle S, Buschek D, Fegert JM, Laurenz P, Lühr M, Marek F, Rassenhofer M, et al. Developing a Safety Planning Smartphone App to Support Adolescents’ Self-Management During Emotional Crises. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111607

Chicago/Turabian StyleGroßmann, Tamara, Jana Hörger, Nadine Bayer, Sophie Bückle, Daniel Buschek, Jörg M. Fegert, Peter Laurenz, Matthias Lühr, Franziska Marek, Miriam Rassenhofer, and et al. 2025. "Developing a Safety Planning Smartphone App to Support Adolescents’ Self-Management During Emotional Crises" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111607

APA StyleGroßmann, T., Hörger, J., Bayer, N., Bückle, S., Buschek, D., Fegert, J. M., Laurenz, P., Lühr, M., Marek, F., Rassenhofer, M., & Oexle, N. (2025). Developing a Safety Planning Smartphone App to Support Adolescents’ Self-Management During Emotional Crises. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111607