SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Risk of New Chronic Conditions: Insights from a Longitudinal Population-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Chronic Conditions and SARS-CoV-2 Infections

2.3.2. Covariates

2.3.3. Residential Address

2.4. Statistical Modeling

2.5. Pooling of Results

2.6. Spatial Heterogeneity

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

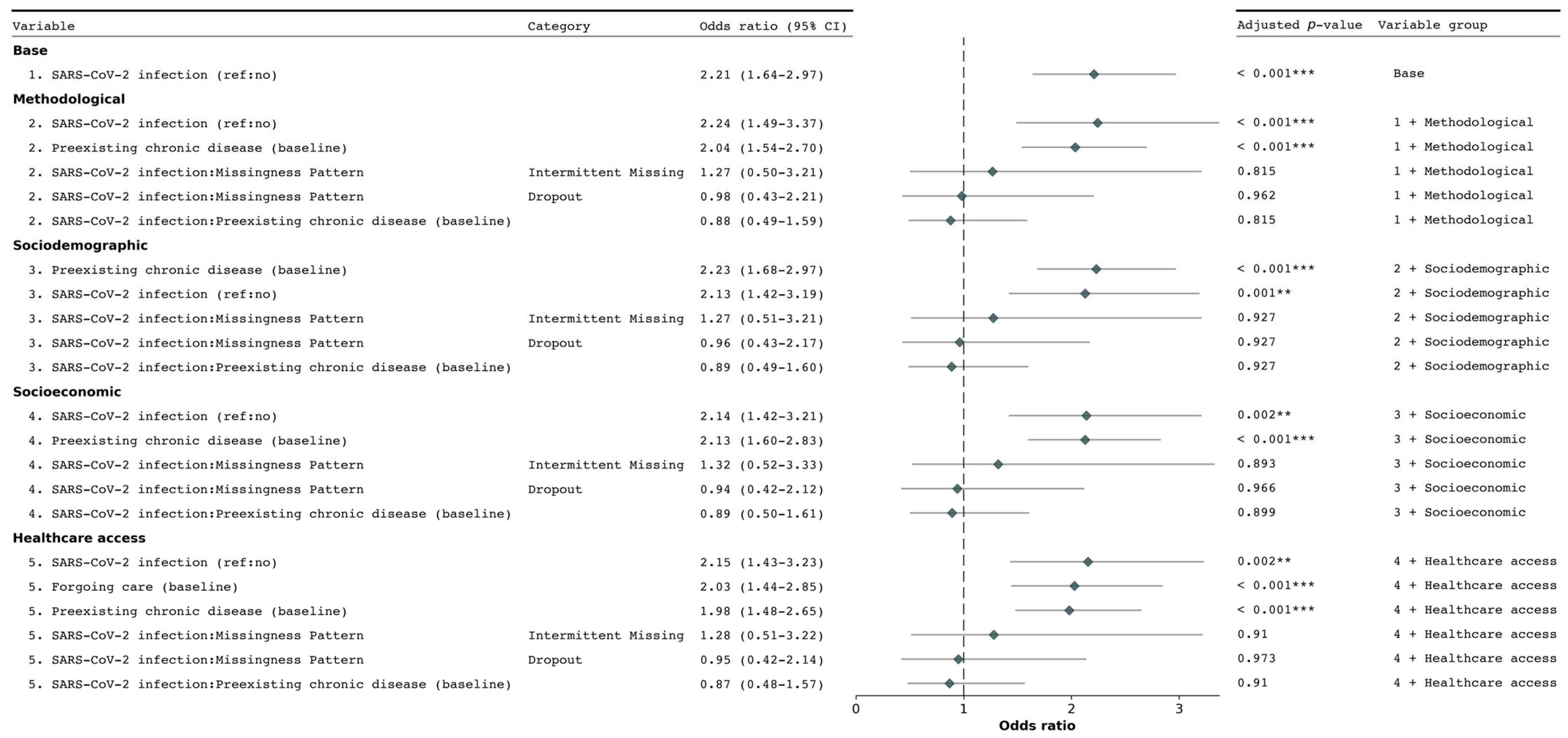

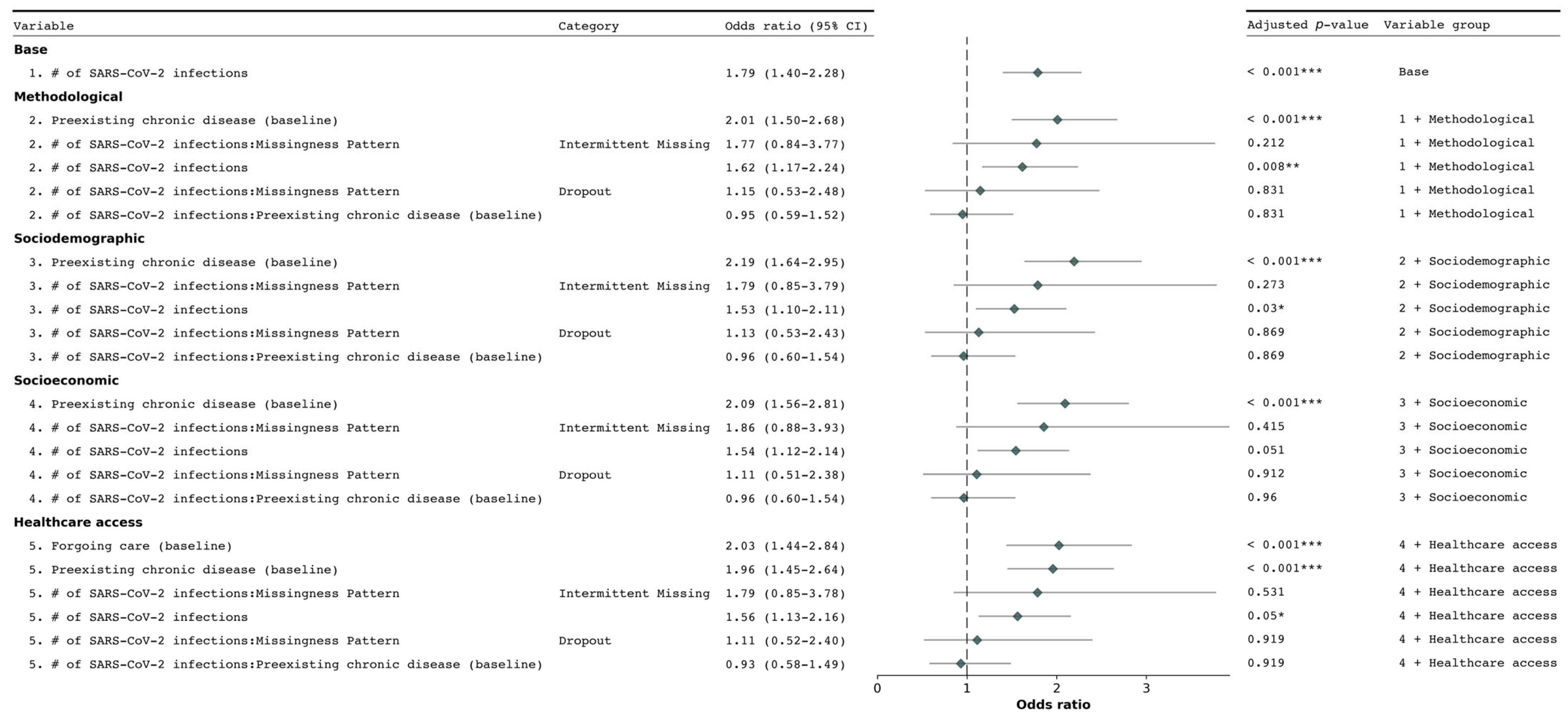

3.2. Determinants of New Chronic Condition Diagnosis

3.3. Spatial Heterogeneity in the Association Between New Diagnosis of Chronic Conditions and SARS-CoV-2 Infections

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, T.-J.; Rabheru, K.; Peisah, C.; Reichman, W.; Ikeda, M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Rhodes, A.; Cheng, A.C.; Peacock, S.J.; Prescott, H.C. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarpazhooh, M.R.; Morovatdar, N.; Avan, A.; Phan, T.G.; Divani, A.A.; Yassi, N.; Stranges, S.; Silver, B.; Biller, J.; Belasi, M.T.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases: An Ecological Study on Data of 185 Countries. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacker, K.A.; Briss, P.A.; Richardson, L.; Wright, J.; Petersen, R. COVID-19 and Chronic Disease: The Impact Now and in the Future. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, 210086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, M.; Braillard, O.; Alcoba, G.; Perone, S.A.; Courvoisier, D.; Chappuis, F.; Guessous, I. COVID-19 Symptoms: Longitudinal Evolution and Persistence in Outpatient Settings. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveed, Z.; García, H.A.V.; Wong, S.; Wilton, J.; McKee, G.; Mahmood, B.; Binka, M.; Rasali, D.; Janjua, N.Z. Association of COVID-19 Infection with Incident Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e238866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xu, E.; Bowe, B.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Xie, Y.; Bowe, B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 594, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Daugherty, S.; Guo, Y.; Heath, K.; Dasmariñas, M.C.; Jubilo, K.G.; Samranvedhya, J.; Lipsitch, M.; Cohen, K. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2021, 373, n1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, M.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Luciano, S.; Harrison, P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236,379 survivors of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.T.S.; Krieger, N. Revealing the Unequal Burden of COVID-19 by Income, Race/Ethnicity, and Household Crowding: US County Versus Zip Code Analyses. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2020, 27, S43–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cafiero, E.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Bloom, L.R.; Fathima, S.; Feigl, A.B.; Gaziano, T.; Hamandi, A.; Mowafi, M.; et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. PGDA Working Papers. Published online 2012. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/gdm/wpaper/8712.html (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, G.; Bassareo, P.P.; Barilla, F.; Romeo, F.; de Gregorio, C.; Mehta, P.; Mehta, J.L. Syndemic: A Synergistic Anthropological Approach to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietzner, M.; Denaxas, S.; Yasmeen, S.; Ulmer, M.A.; Nakanishi, T.; Arnold, M.; Kastenmüller, G.; Hemingway, H.; Langenberg, C. Complex patterns of multimorbidity associated with severe COVID-19 and long COVID. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C.; Riordan, R.; Ford, J.; Matthews, F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W.; Bohlken, J.; Kostev, K. Effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on disease recognition and utilisation of healthcare services in the older population in Germany: A cross-sectional study. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, T. Reduced Cancer Screening Due to Lockdowns of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Reviewing Impacts and Ways to Counteract the Impacts. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 955377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vincentiis, L.; Carr, R.A.; Mariani, M.P.; Ferrara, G. Cancer diagnostic rates during the 2020 ‘lockdown’, due to COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 2018–2019: An audit study from cellular pathology. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 74, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Taeihagh, A.; Tan, S.Y. A scoping review of the impacts of COVID-19 physical distancing measures on vulnerable population groups. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqib, K.; Qureshi, A.S.; Butt, Z.A. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Chronic Illnesses: A Syndemic Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, R.; To, Q.G.; Khalesi, S.; Williams, S.L.; Alley, S.J.; Thwaite, T.L.; Fenning, A.S.; Vandelanotte, C. Depression, Anxiety and Stress During COVID-19: Associations with Changes in Physical Activity, Sleep, Tobacco and Alcohol Use in Australian Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, S.; Trott, M.; Tully, M.; Shin, J.; Barnett, Y.; Butler, L.; McDermott, D.; Schuch, F.; Smith, L. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: A systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021, 7, e000960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, J.; O’brien, W.J.; McGrane, B.; Wadsworth, D.; Batten, J.; Askew, C.D.; Badenhorst, C.; Byrd, E.; Coulter, M.; Draper, N.; et al. Physical activity, mental health and well-being of adults during initial COVID-19 containment strategies: A multi-country cross-sectional analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gisbert, L.; Torres-Sánchez, I.; Ortiz-Rubio, A.; Calvache-Mateo, A.; López-López, L.; Cabrera-Martos, I.; Valenza, M.C. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity in Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magesh, S.; John, D.; Li, W.T.; Li, Y.; Mattingly-App, A.; Jain, S.; Chang, E.Y.; Ongkeko, W.M. Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2134147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Vega, M.F.; Soto-Cabezas, M.; Cárdenas, F.; Martel, K.S.; Valle, A.; Valverde, J.; Vidal-Anzardo, M.; Falcón, M.E.; Munayco, C.V. SARS-CoV-2 prevalence associated to low socioeconomic status and overcrowding in an LMIC megacity: A population-based seroepidemiological survey in Lima, Peru. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 34, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, E.M.; Szefler, S.J. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendenhall, E. The COVID-19 syndemic is not global: Context matters. Lancet 2020, 396, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenzato, L.; Botton, J.; Drouin, J.; Cuenot, F.; Dray-Spira, R.; Weill, A.; Zureik, M. Chronic diseases, health conditions and risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization and in-hospital mortality during the first wave of the epidemic in France: A cohort study of 66 million people. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2021, 8, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Clair, S. Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-Social Context. Med. Anthr. Q. 2003, 17, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Bulled, N.; Ostrach, B.; Mendenhall, E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet 2017, 389, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. We’re Not All in This Together: On COVID-19, Intersectionality, and Structural Inequality. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Cené, C.W.; Chatterjee, A. Covid-19 and Health Equity—Time to Think Big. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.K.; Peterson, E.R.; Balan, D.; Jones, L.; Culp, G.M.; Fine, A.D.; Kulldorff, M. Detecting COVID-19 Clusters at High Spatiotemporal Resolution, New York City, New York, USA, June–July 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1500–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, D.; Sandoval, J.; Vuilleumier, N.; Stringhini, S.; Spechbach, H.; Joost, S.; Kaiser, L.; Guessous, I. Geospatial digital monitoring of COVID-19 cases at high spatiotemporal resolution. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, E393–E394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D.; Loizeau, A.J.; Sandoval, J.L.; Ehrler, F.; Perrier, M.; Ritch, A.; Violot, G.; Santolini, M.; Tzovaras, B.G.; Stringhini, S.; et al. Detection of Spatiotemporal Clusters of COVID-19–Associated Symptoms and Prevention Using a Participatory Surveillance App: Protocol for the @choum Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e30444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.L.; Derakhshan, S.; Blackwood, L.; Lee, L.; Huang, Q.; Habets, M.; Cutter, S.L. Spatial disparities of COVID-19 cases and fatalities in United States counties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, J.; Castro, M.C. Spatial analysis of COVID-19 clusters and contextual factors in New York City. Spat. Spatio-temporal Epidemiol. 2020, 34, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.J.; Huang, P.; Yin, F.; Luo, X.I.; Almquist, Z.W.; Hipp, J.R.; Butts, C.T. Spatial heterogeneity can lead to substantial local variations in COVID-19 timing and severity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24180–24187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahasan, R.; Hossain, M. Leveraging GIS and spatial analysis for informed decision-making in COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 10, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhera, R.K.; Wadhera, P.; Gaba, P.; Figueroa, J.F.; Maddox, K.E.J.; Yeh, R.W.; Shen, C. Variation in COVID-19 Hospitalizations and Deaths Across New York City Boroughs. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 2192–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysson, H.; Pennacchio, F.; Wisniak, A.; Zaballa, M.E.; Pullen, N.; Collombet, P.; Lorthe, E.; Joost, S.; Balavoine, J.-F.; Bachmann, D.; et al. Specchio-COVID19 cohort study: A longitudinal follow-up of SARS-CoV-2 serosurvey participants in the canton of Geneva, Switzerland. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringhini, S.; Wisniak, A.; Piumatti, G.; Azman, A.S.; Lauer, S.A.; Baysson, H.; De Ridder, D.; Petrovic, D.; Schrempft, S.; Marcus, K.; et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Geneva, Switzerland (SEROCoV-POP): A population-based study. Lancet 2020, 396, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringhini, S.; Zaballa, M.-E.; Perez-Saez, J.; Pullen, N.; de Mestral, C.; Picazio, A.; Pennacchio, F.; Wisniak, A.; Richard, A.; Baysson, H.; et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after the second pandemic peak. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 600–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringhini, S.; Zaballa, M.-E.; Pullen, N.; Perez-Saez, J.; de Mestral, C.; Loizeau, A.J.; Lamour, J.; Pennacchio, F.; Wisniak, A.; Dumont, R.; et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies 6 months into the vaccination campaign in Geneva, Switzerland, 1 June to 7 July 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaballa, M.-E.; Perez-Saez, J.; de Mestral, C.; Pullen, N.; Lamour, J.; Turelli, P.; Raclot, C.; Baysson, H.; Pennacchio, F.; Villers, J.; et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and cross-variant neutralization capacity after the Omicron BA.2 wave in Geneva, Switzerland: A population-based study. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2022, 24, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringhini, S.; Zaballa, M.-E.; Pullen, N.; de Mestral, C.; Perez-Saez, J.; Dumont, R.; Picazio, A.; Pennacchio, F.; Dibner, Y.; Yerly, S.; et al. Large variation in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence among essential workers in Geneva, Switzerland. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welcome to GeoAdmin API’s Documentation!—GeoAdmin API 3.0 Documentation. Available online: https://api3.geo.admin.ch/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Glmer Function—RDocumentation. Available online: https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/lme4/versions/1.1-35.4/topics/glmer (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.; Van Der Linden, W.; Heeringa, S.; Long, J.S.; Snijders, T. Multilevel Modeling Using R; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Geographically+Weighted+Regression%3A+The+Analysis+of+Spatially+Varying+Relationships+-p-9780471496168 (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Oshan, T.M.; Li, Z.; Kang, W.; Wolf, L.J.; Fotheringham, A.S. MGWR: A python implementation of multiscale geographically weighted regression for investigating process spatial heterogeneity and scale. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, A.B.; Harrison, E.M.; Green, C.A.; Hardwick, H.E.; Pius, R.; Norman, L.; Holden, K.A.; Read, J.M.; Dondelinger, F.; Carson, G.; et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2020, 369, m1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, S.E.; Healy, B.C.; Zurawski, J.; Severson, C.; Kaplan, T.; Stazzone, L.; Galetta, K.; Chitnis, T.; Houtchens, M.K. COVID-19 severity is associated with worsened neurological outcomes in multiple sclerosis and related disorders. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 63, 103946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, E.J.; Rolfes, M.A.; O’Halloran, A.; Anderson, E.J.; Bennett, N.M.; Billing, L.; Chai, S.; Dufort, E.; Herlihy, R.; Kim, S.; et al. Acute cardiovascular events associated with influenza in hospitalized adults: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Sun, X.; Yan, Z.; Hu, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Yin, P.; et al. Altered Lipid Metabolism in Recovered SARS Patients Twelve Years after Infection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D.; Ladoy, A.; Choi, Y.; Jacot, D.; Vuilleumier, S.; Guessous, I.; Joost, S.; Greub, G. Environmental and geographical factors influencing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 over 2 years: A fine-scale spatiotemporal analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1298177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B.; Waitzberg, R.; Israeli, A.; Hartal, M.; Davidovitch, N. Addressing vaccine hesitancy and access barriers to achieve persistent progress in Israel’s COVID-19 vaccination program. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diesel, J.; Sterrett, N.; Dasgupta, S.; Kriss, J.L.; Barry, V.; Esschert, K.V.; Whiteman, A.; Cadwell, B.L.; Weller, D.; Qualters, J.R.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Adults—United States, December 14, 2020–May 22, 2021. Mmwr-Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.R.; A Richardson, E.; Mitchell, R.J.; Shortt, N.K. Environmental justice and health: The implications of the socio-spatial distribution of multiple environmental deprivation for health inequalities in the United Kingdom. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2010, 35, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinoudis, G.; Padellini, T.; Bennett, J.; Davies, B.; Ezzati, M.; Blangiardo, M. Long-term exposure to air-pollution and COVID-19 mortality in England: A hierarchical spatial analysis. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodby, B.; Arnold, M.M.; Valacchi, G. SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 pathogenesis, and exposure to air pollution: What is the connection? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1486, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herath, S.; Mansour, A.; Bentley, R. Urban density, household overcrowding and the spread of COVID-19 in Australian cities. Health Place 2024, 89, 103298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajnzylber, J.; Regan, J.; Coxen, K.; Corry, H.; Wong, C.; Rosenthal, A.; Worrall, D.; Giguel, F.; Piechocka-Trocha, A.; Atyeo, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.L.; Mertens, A.N.; Crider, Y.S.; Nguyen, A.; Pokpongkiat, N.N.; Djajadi, S.; Seth, A.; Hsiang, M.S.; Colford, J.M., Jr.; Reingold, A.; et al. Substantial underestimation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeling, R.W.; Wedderburn, C.J.; Garcia, P.J.; Boeras, D.; Fongwen, N.; Nkengasong, J.; Sall, A.; Tanuri, A.; Heymann, D.L. Serology testing in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e245–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Overall, n= 17,053 1 | 2021, n = 6127 1 | 2022, n = 5978 1 | 2023, n = 4948 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—Baseline | <0.001 | ||||

| 18–34 | 2073 (12%) | 869 (14%) | 666 (11%) | 538 (11%) | |

| 35–49 | 5626 (33%) | 2058 (34%) | 2000 (33%) | 1568 (32%) | |

| 50–64 | 6227 (37%) | 2197 (36%) | 2176 (36%) | 1854 (37%) | |

| 65–79 | 2909 (17%) | 944 (15%) | 1036 (17%) | 929 (19%) | |

| 80+ | 218 (1.3%) | 59 (1.0%) | 100 (1.7%) | 59 (1.2%) | |

| Sex—Baseline | 0.2 | ||||

| Female | 10,028 (59%) | 3547 (58%) | 3543 (59%) | 2938 (59%) | |

| Male | 7025 (41%) | 2580 (42%) | 2435 (41%) | 2010 (41%) | |

| Insurance deductible—Baseline | >0.9 | ||||

| Missing 3 | 4 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 2 (<0.1%) | |

| 300 CHF | 5829 (34%) | 2058 (34%) | 2070 (35%) | 1701 (34%) | |

| 500 CHF | 2908 (17%) | 1046 (17%) | 1024 (17%) | 838 (17%) | |

| 1000 CHF | 693 (4.1%) | 252 (4.1%) | 237 (4.0%) | 204 (4.1%) | |

| 1500 CHF | 1277 (7.5%) | 461 (7.5%) | 442 (7.4%) | 374 (7.6%) | |

| 2000 CHF | 364 (2.1%) | 136 (2.2%) | 126 (2.1%) | 102 (2.1%) | |

| 2500 CHF | 4772 (28%) | 1730 (28%) | 1648 (28%) | 1394 (28%) | |

| Don’t know/don’t wish to answer | 873 (5.1%) | 326 (5.3%) | 310 (5.2%) | 237 (4.8%) | |

| No Swiss health insurance | 333 (2.0%) | 117 (1.9%) | 120 (2.0%) | 96 (1.9%) | |

| Education level—Baseline | 0.3 | ||||

| Missing 3 | 2 (<0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | |

| Other | 24 (0.1%) | 5 (<0.1%) | 13 (0.2%) | 6 (0.1%) | |

| Primary | 666 (3.9%) | 240 (3.9%) | 252 (4.2%) | 174 (3.5%) | |

| Secondary | 5366 (31%) | 1941 (32%) | 1894 (32%) | 1531 (31%) | |

| Tertiary | 10,995 (64%) | 3941 (64%) | 3818 (64%) | 3236 (65%) | |

| Work situation—Baseline | <0.001 | ||||

| Missing 3 | 4 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 2 (<0.1%) | |

| Freelance/sole trader | 1247 (7.3%) | 449 (7.3%) | 435 (7.3%) | 363 (7.3%) | |

| Other economically inactive | 1416 (8.3%) | 530 (8.7%) | 485 (8.1%) | 401 (8.1%) | |

| Retired | 3294 (19%) | 1046 (17%) | 1199 (20%) | 1049 (21%) | |

| Salaried | 10,659 (63%) | 3942 (64%) | 3712 (62%) | 3005 (61%) | |

| Unemployed | 433 (2.5%) | 159 (2.6%) | 146 (2.4%) | 128 (2.6%) | |

| Household income—Baseline | 0.4 | ||||

| Missing 3 | 10 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) | 3 (<0.1%) | |

| Don’t know/don’t wish to answer | 2988 (18%) | 1096 (18%) | 1050 (18%) | 842 (17%) | |

| High | 2520 (15%) | 888 (14%) | 891 (15%) | 741 (15%) | |

| Low | 2348 (14%) | 860 (14%) | 846 (14%) | 642 (13%) | |

| Middle | 9187 (54%) | 3282 (54%) | 3185 (53%) | 2720 (55%) | |

| Occupation—Baseline | 0.059 | ||||

| Missing 3 | 12 (<0.1%) | 3 (<0.1%) | 4 (<0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | |

| Blue collar workers | 1481 (8.7%) | 564 (9.2%) | 540 (9.0%) | 377 (7.6%) | |

| Higher-grade white-collar workers | 4442 (26%) | 1596 (26%) | 1530 (26%) | 1316 (27%) | |

| Independent workers | 310 (1.8%) | 90 (1.5%) | 121 (2.0%) | 99 (2.0%) | |

| Lower-grade white collar workers | 4373 (26%) | 1557 (25%) | 1549 (26%) | 1267 (26%) | |

| Other | 869 (5.1%) | 319 (5.2%) | 303 (5.1%) | 247 (5.0%) | |

| Professional-Managers | 5566 (33%) | 1998 (33%) | 1931 (32%) | 1637 (33%) | |

| Nationality—Baseline | 0.11 | ||||

| Missing 3 | 1 (<0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Foreigner | 2846 (17%) | 1037 (17%) | 1029 (17%) | 780 (16%) | |

| Swiss | 14,206 (83%) | 5090 (83%) | 4948 (83%) | 4168 (84%) | |

| Living status—Baseline | 0.015 | ||||

| Missing 3 | 5 (<0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (<0.1%) | 2 (<0.1%) | |

| Cohabitation | 1152 (6.8%) | 470 (7.7%) | 374 (6.3%) | 308 (6.2%) | |

| Single | 2603 (15%) | 925 (15%) | 918 (15%) | 760 (15%) | |

| Single parent | 1150 (6.7%) | 417 (6.8%) | 392 (6.6%) | 341 (6.9%) | |

| With partner and kids | 7368 (43%) | 2661 (43%) | 2616 (44%) | 2091 (42%) | |

| With partner, without kids | 4775 (28%) | 1654 (27%) | 1675 (28%) | 1446 (29%) | |

| Chronic condition—Baseline | 4426 (26%) | 1537 (25%) | 1571 (26%) | 1318 (27%) | 0.14 |

| Missing 3 | 2 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Forgoing healthcare—Baseline | 1447 (8.5%) | 512 (8.4%) | 515 (8.6%) | 420 (8.5%) | 0.9 |

| Missing 3 | 3 (<0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (<0.1%) | 2 (<0.1%) | |

| Health event—New diagnosis | 313 (1.8%) | 82 (1.3%) | 112 (1.9%) | 119 (2.4%) | <0.001 |

| Health event—Worsening conditions | 190 (1.1%) | 53 (0.9%) | 76 (1.3%) | 61 (1.2%) | 0.066 |

| Health event—SARS-CoV-2 infection | 1982 (12%) | 262 (4.3%) | 1131 (19%) | 589 (12%) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Ridder, D.; Uppal, A.; Rouzinov, S.; Lamour, J.; Zaballa, M.-E.; Baysson, H.; Joost, S.; Stringhini, S.; Guessous, I.; Nehme, M., on behalf of the Specchio-COVID19 Study Group. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Risk of New Chronic Conditions: Insights from a Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020166

De Ridder D, Uppal A, Rouzinov S, Lamour J, Zaballa M-E, Baysson H, Joost S, Stringhini S, Guessous I, Nehme M on behalf of the Specchio-COVID19 Study Group. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Risk of New Chronic Conditions: Insights from a Longitudinal Population-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020166

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Ridder, David, Anshu Uppal, Serguei Rouzinov, Julien Lamour, María-Eugenia Zaballa, Hélène Baysson, Stéphane Joost, Silvia Stringhini, Idris Guessous, and Mayssam Nehme on behalf of the Specchio-COVID19 Study Group. 2025. "SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Risk of New Chronic Conditions: Insights from a Longitudinal Population-Based Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020166

APA StyleDe Ridder, D., Uppal, A., Rouzinov, S., Lamour, J., Zaballa, M.-E., Baysson, H., Joost, S., Stringhini, S., Guessous, I., & Nehme, M., on behalf of the Specchio-COVID19 Study Group. (2025). SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Risk of New Chronic Conditions: Insights from a Longitudinal Population-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020166