Food Safety in Informal Markets: How Knowledge and Attitudes Influence Vendor Practices in Namibia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Respondents

3.2. Food Handlers Trained in Food Safety

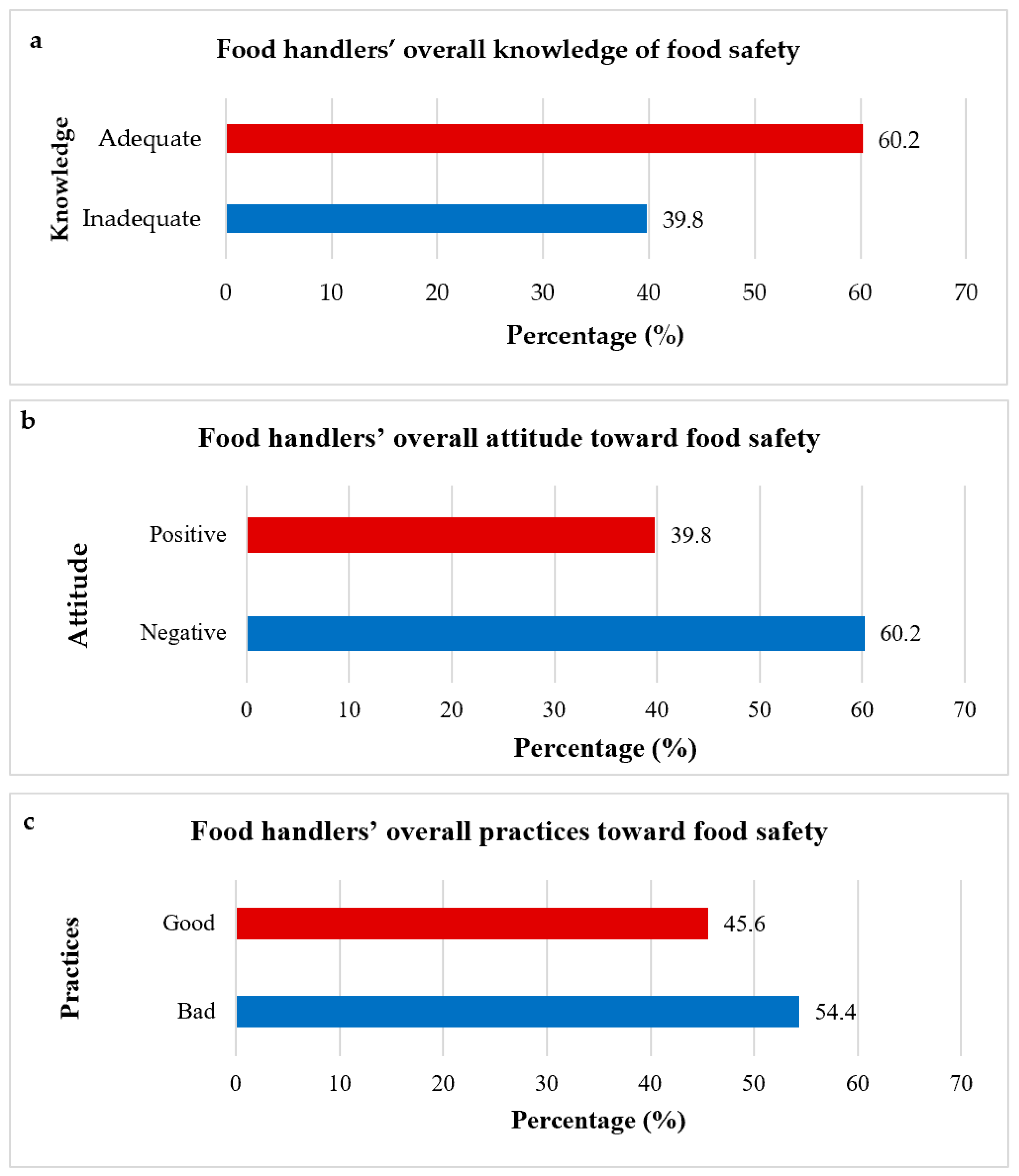

3.3. Food Handlers’ Level of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices on Food Safety

3.4. Correlation Between Food Handlers’ Sociodemographic Characteristics and Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices

3.5. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis of Food Handlers’ Sociodemographic Characteristics and Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Food Safety

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

4.2. Food Handlers’ Knowledge of Food Safety

4.3. Food Handlers’ Attitudes Toward Food Safety

4.4. Food Handlers’ Food Safety Practices

4.5. Interrelationship Between Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices

4.6. Relationship Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Food Safety KAP

4.7. Policy Implications

4.8. Public Health Implications

4.9. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

4.10. Recommendations

- -

- Implement structured, context-specific food safety training tailored to local food handlers’ education levels and daily challenges. Training content should prioritise identified gaps, particularly in temperature control, food storage, and personal hygiene practices.

- -

- Introduce behaviour change interventions that address the disconnect between knowledge and attitudes observed in the study. Interactive sessions, peer role-modelling, and incentive-based learning could improve motivation and translate knowledge into safer practices.

- -

- Establish routine and visible food safety inspections, supported by local health authorities, to reinforce compliance. Inspections should focus on areas highlighted in the study as weak, including the use of protective clothing, handwashing, and utensil hygiene.

- -

- Create informal vendor certification programmes. Vendors who demonstrate improved food safety practices could be prioritised for better stall locations or reduced rental fees, offering a positive incentive structure.

- -

- Promote continuous learning by conducting refresher training and community-based health education campaigns through radio, posters, and trade fairs, targeting the majority of vendors who expressed a willingness to learn.

- -

- Leverage experienced food handlers as peer educators, since the study showed that work experience positively influenced knowledge and practices. Peer-led training could bridge generational knowledge gaps and foster a culture of compliance.

4.11. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zanin, L.M.; da Cunha, D.T.; de Rosso, V.V.; Capriles, V.D.; Stedefeldt, E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in food safety: An integrative review. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100 Pt 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, T. The Nature and Operations of Informal Food Vendors in Cape Town. Urban Forum 2019, 30, 443–459. [Google Scholar]

- Shajulin, B. Informal Marketing and Livelihood of Marginal Communities in Urban Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. In Perspectives on Geographical Marginality; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Boatemaa, K.S.; Shawn, A.; Paul, C. Narrative explorations of the role of the informal food sector in food flows and sustainable transitions during the COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS Sustain. Transform. 2022, 1, e0000038. [Google Scholar]

- Elsahoryi, N.A.; Olaimat, A.; Abu Shaikha, H.; Tabib, B.; Holley, R. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of street vendors: A cross-sectional study in Jordan. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 3870–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstikj, A.; Egurrola Hernández, E.A.; Giorgi, E.; Garnica Monroy, R. Evaluating the availability, accessibility, and affordability of fresh food in informal food environments in five Mexican cities. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.J.; Ali, M.; Alam, K.E.; Mamun, M.; Bhuiyan, M.I.H.; Bhandari, P.; Chalise, R.; Naem, S.M.Z.; Rahi, A.I.; Islam, K.; et al. Assessing knowledge, attitude, and practices (kap) of food safety among dhaka city’s street food vendors: A public health issue. Res. Sq. 2024; Preprint (Version 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, E.; Mutua, F.; Grace, D.; Lambertini, E.; Thomas, L.F. Foodborne zoonoses control in low- and middle-income countries: Identifying aspects of interventions relevant to traditional markets which act as hurdles when mitigating disease transmission. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 913560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, D.T. Risk Perception, Communication and Behaviour Towards Food Safety Issues. Foods 2025, 14, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo-Tham, R.; Appiah-Brempong, E.; Vampere, H.; Acquah-Gyan, E.; Gyimah Akwasi, A. Knowledge on Food Safety and Food-Handling Practices of Street Food Vendors in Ejisu-Juaben Municipality of Ghana. Adv. Public Health 2020, 2020, 4579573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letuka, P.; Nkhebenyane, J.; Thekisoe, O. Street food handlers’ food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices and consumers’ perceptions about street food vending in Maseru, Lesotho. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Banna, M.H.; Khan, M.S.I.; Rezyona, H.; Seidu, A.A.; Abid, M.T.; Ara, T.; Kundu, S.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Hagan, J.E., Jr.; Tareq, M.A.; et al. Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Food Service Staff in Bangladeshi Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Banna, H.; Kundu, S.; Brazendale, K.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Disu, T.R.; Seidu, A.-A.; Okyere, J.; Khan, S.I. Knowledge and awareness about food safety, foodborne diseases, and microbial hazards: A cross-sectional study among Bangladeshi consumers of street-vended foods. Food Control 2022, 134, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, G.; Jordan, B.; Kurt, W.; Danielle, R.; Daniel, F. Informal vendors and food systems planning in an emerging African city. Food Policy 2021, 103, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.P.; Linnemann, A.R.; Luning, P.A. Food safety knowledge, self-reported hygiene practices, and street food vendors’ perceptions of current hygiene facilities and services—An Ecuadorean case. Food Control 2023, 144, 109377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, N.V.; Tabit, F.T. The food safety knowledge of street food vendors and the sanitary conditions of their street food vending environment in the Zululand District, South Africa. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mphaga, K.V.; Moyo, D.; Rathebe, P.C. Unlocking food safety: A comprehensive review of South Africa’s food control and safety landscape from an environmental health perspective. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickanor, N.; Kazembe, L.; Crush, J.; Wagner, J. The Supermarket Revolution and Food Security in Namibia; Southern African Migration Programme: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, D. Burden of foodborne disease in low-income and middle-income countries and opportunities for scaling food safety interventions. Food Secur. 2023, 15, 1475–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, M.S.; Susanna, D. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers at kitchen premises in the Port ‘X’ area, North Jakarta, Indonesia 2018. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2021, 10, 9215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, C. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques; New Age International: New Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Z.; Afreen, A.; Hassan, M.U.; Ahmad, H.; Anjum, N.; Waseem, M. Exposure of Food Safety Knowledge and Inadequate Practices among Food Vendors at Rawalpindi; the Fourth Largest City of Pakistan. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 5, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Alqurashi, N.A.; Priyadarshini, A.; Jaiswal, A.K. Evaluating Food Safety Knowledge and Practices among Foodservice Staff in Al Madinah Hospitals, Saudi Arabia. Safety 2019, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhana, Z.; Sutradhar, N.; Mustafa, T.; Naser, M.N. Food Safety and Environmental Awareness of Street Food Vendors of the Dhaka University Campus, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Zool. 2020, 48, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, J.; Cunningham, S.A.; Eeckels, R.; Herbst, K. Data cleaning: Detecting, diagnosing, and editing data abnormalities. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreb, N.A.; Priyadarshini, A.; Jaiswal, A.K. Knowledge of food safety and food handling practices amongst food handlers in the Republic of Ireland. Food Control 2017, 80, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.H.; Le, N.H.; Le, A.T.N.; Minh, N.N.T.; Nuorti, J.P. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and training needs of food-handlers in large canteens in Southern Vietnam. Food Control 2015, 57, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaki, M.Y.; Bavorova, M. Food safety knowledge of food vendors of higher educational institutions in Bauchi state, Nigeria. Food Control 2019, 106, 106703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.X.; Do, H.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Boggiano, V.; Le, H.T.; Le, X.T.T.; Trinh, N.B.; Do, K.N.; Nguyen, C.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; et al. Evaluating Food Safety Knowledge and Practices of Food Processors and Sellers Working in Food Facilities in Hanoi, Vietnam. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safari, Y.; Maleki, S.; Karimyan, K.; Arfaeinia, H.; Gupta, V.K.; Yoosefpour, N.; Shalyari, N.; Akhlaghi, M.; Sharfi, H.; Ziapour, A. Data for interventional role of training in changing the knowledge and attitudes of urban mothers towards food hygiene (A case study of Ravansar Township, Kermanshah, Iran). Data Brief 2018, 19, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam Siddiky, N.; Khan, S.R.; Sarker, S.; Bhuiyan, M.K.J.; Mahmud, A.; Rahman, T.; Ahmed, M.M.; Samad, M.A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of chicken vendors on food safety and foodborne pathogens at wet markets in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Food Control 2022, 131, 108456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.H.; Akbar, A.; Sadiq, M.B. Cross sectional study on food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers in Lahore district, Pakistan. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaili, T.M.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Krasneh, H.D.A. Food safety knowledge among foodservice staff at the universities in Jordan. Food Control 2018, 89, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhebenyane, J.S.; Lues, R. The knowledge, attitude, and practices of food handlers in central South African hospices. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 2598–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayalakshmi, R.; Srinivasan, J.; Ruban, R.M.; Sahila, C.; Vengatesan, G. Street Venders’ Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices and Consumers’ Preference About Street Food Marketing in Chennai City. South East. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, XXV, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erah, F.O.; Otobhiale, B.I.; Ekhator, N.P.; Ehis, B.; Aniaku, E.; Okoduwa, F.O.; Okoene, O.S.; Isibor, B.; Edeawe, P. Knowledge, attitude and practice of food hygiene and safety among food vendors in a rural tertiary health facility in south South Nigeria. World J. Adv. Pharm. Med. Res. 2024, 7, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Banna, M.H.A.; Sayeed, A.; Akter, S.; Aktar, A.; Islam, M.A.; Proshad, R.; Khan, M.S.I. Effect of vendors’ socio-demography and other factors on hygienic practices of street food shops. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2021, 24, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.Z.; Islam, M.S.; Salauddin, M.; Zafr, A.H.A.; Alam, S. Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Chotpoti Vendors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J. Enam Med. Coll. 2017, 7, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T.A.; Basile, K.A.; Canonico, E. Telework: Outcomes and Facilitators for Employees. In The Cambridge Handbook of Technology and Employee Behavior; Landers, R.N., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngalangi, P. Analysis of Food Safety and Food Handling Knowledge Among Street Food Vendors in Selected Local Food Markets in Windhoek. Master’s Thesis, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11070/3566 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

| Domain | Sub-Domain | Number of Items |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | General knowledge, food contamination, hygiene, storage and temperature | 12 |

| Attitudes | Food safety perception, willingness to comply | 7 |

| Practices | Hygiene behaviours, food handling, cleanliness | 10 |

| Demographic Variable | Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 62 | 60.2 |

| Male | 41 | 39.8 | |

| Age | 18–20 years | 4 | 3.9 |

| 21–29 years | 20 | 19.4 | |

| 30–39 years | 35 | 34.0 | |

| 40–49 years | 36 | 35.0 | |

| 50–59 years | 8 | 7.8 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 26 | 25.2 |

| Single | 59 | 57.3 | |

| Divorced | 10 | 9.7 | |

| Widowed | 8 | 7.8 | |

| Educational Level | No education | 21 | 20.4 |

| Primary | 39 | 37.9 | |

| Secondary | 34 | 33.0 | |

| Tertiary | 9 | 8.7 | |

| Working Experience | ≤three years | 20 | 19.4 |

| 4–10 years | 39 | 37.9 | |

| 11–15 years | 24 | 23.3 | |

| 16–20 years | 14 | 13.6 | |

| ≥21 years | 6 | 5.8 |

| Training Variable | Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food safety training (n = 103) | Yes | 16 | 15.5 |

| No | 87 | 84.5 | |

| Venue of training (n = 16) | Oshakati | 8 | 50.0 |

| Otjiwarongo | 2 | 12.5 | |

| Windhoek | 6 | 37.5 | |

| The year of training (n = 16) | 2018 | 1 | 6.3 |

| 2019 | 1 | 6.3 | |

| 2020 | 3 | 18.8 | |

| 2021 | 4 | 25.0 | |

| 2022 | 7 | 43.8 |

| Practices | Attitudes | Knowledge | Sex | Age | Marital Status | Education Level | Work Experience | Training | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practices | 1 | −0.745 ** | 0.745 ** | 0.051 | −0.021 | −0.144 | 0.113 | 0.172 | 0.038 |

| Attitudes | −0.745 ** | 1 | −1 ** | −0.054 | 0.032 | 0.073 | −0.126 | −0.229 * | −0.02 |

| Knowledge | 0.745 ** | −1 ** | 1 | 0.054 | −0.032 | −0.073 | 0.126 | 0.229 * | 0.02 |

| Sex | 0.051 | −0.054 | 0.054 | 1 | 0.052 | −0.024 | 0.052 | 0.064 | −0.02 |

| Age | −0.021 | 0.032 | −0.032 | 0.052 | 1 | 0.061 | 0.176 | 0.605 ** | −0.035 |

| Marital status | −0.144 | 0.073 | −0.073 | −0.024 | 0.061 | 1 | 0.094 | 0.052 | −0.033 |

| Educational level | 0.113 | −0.126 | 0.126 | 0.052 | 0.176 | 0.094 | 1 | 0.467 ** | −0.096 |

| Work experience | 0.172 | −0.229 * | 0.229 * | 0.064 | 0.605 ** | 0.052 | 0.467 ** | 1 | −0.034 |

| Training | 0.038 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.035 | −0.033 | −0.096 | −0.034 | 1 |

| Independent Variables | Knowledge | Attitudes | Practices | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β Coefficient | p-Value | β Coefficient | p-Value | β Coefficient | p-Value | |

| Sex | 0.041 | 0.674 | −0.170 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.898 |

| Age | −0.265 | 0.002 * | 0.079 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.903 |

| Marital Status | −0.075 | 0.440 | −0.091 | 0.421 | −0.092 | 0.180 |

| Education Level | −0.003 | 0.975 | −0.077 | 0.940 | 0.035 | 0.655 |

| Work Experience | 0.393 | 0.003 * | −0.162 | 0.000 | −0.014 | 0.000 ** |

| Training | 0.022 | 0.818 | −0.064 | 0.276 | 0.023 | 0.735 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheehama, W.L.N.; Singh, T. Food Safety in Informal Markets: How Knowledge and Attitudes Influence Vendor Practices in Namibia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040631

Sheehama WLN, Singh T. Food Safety in Informal Markets: How Knowledge and Attitudes Influence Vendor Practices in Namibia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040631

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheehama, Winnie L. N., and Tanusha Singh. 2025. "Food Safety in Informal Markets: How Knowledge and Attitudes Influence Vendor Practices in Namibia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040631

APA StyleSheehama, W. L. N., & Singh, T. (2025). Food Safety in Informal Markets: How Knowledge and Attitudes Influence Vendor Practices in Namibia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040631