Pubic Lice (Pthirus pubis): History, Biology and Treatment vs. Knowledge and Beliefs of US College Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

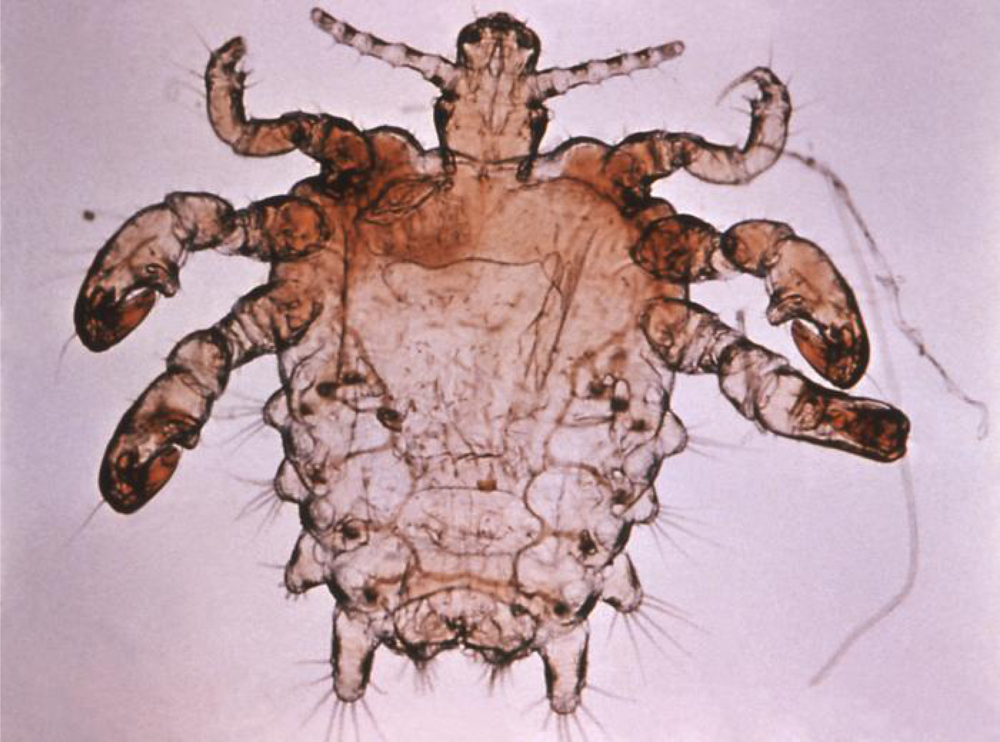

1.1. Pubic lice Biology and History

1.2. Pubic Lice Incidence in Recent Surveys

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

4. Conclusions

References

- Newsome, JH; Fiore, JL, Jr; Hackett, E. Treatment of infestation with Phthirus pubis: comparative efficacies of synergized pyrethrins and gamma-benzene hexachloride. Sex. Transm. Dis 1979, 6, 203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Mimouni, D; Grotto, I; Haviv, J; Gdalevich, M; Huerta, M; Shpilberg, O. Secular trends in epidemiology of pediculosis capitis and pubis among Israeli soldiers: a 27-year follow-up. Int. J. Derm 2001, 40, 637–639. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, JA; Otero, L; Espinosa, E; Sanchez, C; Junquera, ML; Vazquez, F. Phthirus pubis in a sexually transmitted disseases unit: a study of 14 years. Sex. Transm. Dis 2003, 30, 292–296. [Google Scholar]

- Tanfer, K; Cubbins, LA; Billy, JOG. Gender, race, class and self-reported sexually transmitted disease incidence. Fam. Planning Perspect 1995, 27, 196–292. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe-Salas, F; Rio-Chiriboga, C; Conde-Glez, CJ; Juarez-Figueroa, LM; Uribe-Zaga, PM; Calderon-Jaimes, E; Hernandez-Avila, M. Prevalence, incidence, and determinants of syphillis in female commercial sex workers in Mexico City. Am. Sex. Transm. Dis 1996, 23, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pierzchalski, JL; Bretl, DA; Matson, SC. Phthirus pubis as a predictor for chlamydia infections in adolescents. Sex. Transm. Dis 2002, 29, 331–334. [Google Scholar]

- Flinders, DC; DeSchweinitz, P. Pediculosis and scabies. Am. Fam. Phys 2004, 69, 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bignell, C. Lice and scabies. Medicine 2005, 33, 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Orion, E; Hagit, M; Wolf, R. Ectoparasitic sexually transmitted diseases: Scabies and Pediculosis. Clin. In. Derm 2004, 22, 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kenward, H. Pubic lice in Roman and medieval Britain. Trends parasitol 2001, 71, 167–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rick, FM; Rocha, GC; Dittmar, K; Combra, CE, Jr; Reinhard, K; Bouchet, F; Ferreira, LF; Araujo, A. Crab louse infestation in pre-Columbian America. J. Parasitol 2002, 88, 1266–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, KJ; Buikstra, J. Louse infestation of the Chiribaya culture, southern Peru: variation in prevalence by age and sex. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, CJ; Elston, DM. Pediculosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2004, 50, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, JH. The epidemiology, Diagnosis, Management, and prevention of Ectoparasitic diseases in travelers. J. Trav. Med 2006, 13, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, BM. The diagnosis and treatment of scabies and pubic lice. Primary Care Update for OB/GYNS 1996, 3, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, PA. Scabies and Pediculosis Pubis: An update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin. Infect. Dis 2007, 44, S153–S159. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, SK; Barker, SC. Infestation of people with lice in Kathmandu and Pokhara, Nepal. Med. Vet. Entomol 2004, 18, 212–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, G. Factors associated with pediculosis pubis and scabies. Genitourin. Med 1992, 68, 294–295. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, JK; Moore, NB; Earle, JR; Davis, R. Sexual attitudes and behavior at four universities: do region, race, and/or religion matter? Adolescence 2008, 43, 189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, B. Stigma as a barrier to treatment of sexually transmitted infection in the American deep south: issues of race, gender and poverty. Soc. Sci. Med 2003, 57, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, B. The stigma of sexually transmitted infections: Knowledge, Attitudes, and an educationally-based intervention. Health Educ. Monogr. ser 2008, 25, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | Safety profile/use | Efficacy | Resistance of insect to treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.33% pyrethrins + PBO shampoo | Excellent

Apply to hair, wash off after 10 min. | 95% ovicidal in Susceptible strains | Increasing |

| 1% to 5% permethrin cream rinse | Excellent

1% creme rinse, wash off after 10 min. | 2 week residual | Increasing |

| 0.5% malathion lotion shampoo (not available in US) | Flammable, organophosphate poisoning risks. | 95% ovicidal in susceptible strains, rapid killing, good residual | Increasing |

| 1% lindane lotion and shampoo (not recommended in the US) | Potential CNS toxicity from organochlorine poisoning. Only use as last resort Wash off after 4 min. | 95% ovicidal, no residual | Increasing |

| Ivermectin 0.8 % shampoo (not available in US) | Excellent

Apply to hair, wash off after 5 min. | Excellent | None |

| Question | Yes | No | N/A |

|---|---|---|---|

| Which of the following would you use to treat the environment if you had pubic lice? | |||

| 1. Buy new bedding | 690 | 92 | 0 |

| 2. Wash clothing | 759 | 19 | 4 |

| 3. Wash bed linens | 760 | 17 | 5 |

| 4. Spray clothing with insecticide for lice | 659 | 116 | 7 |

| 5. Spray bed linens with insecticide for lice | 674 | 106 | 2 |

| 6. Other treatment | 716 | 66 | 0 |

| 7. No special treatment of the environment is required | 86 | 689 | 7 |

| Can pubic lice be transmitted from one person to another through... | |||

| 8. Shared clothing with a person who has them? | 735 | 44 | 3 |

| 9. Skin to skin contact with the affected area of a person who has them? | 724 | 54 | 4 |

| 10. Generally sharing a living space but not sleeping with someone who has them? | 549 | 231 | 2 |

| 11. Using a toilet seat after someone who has them? | 582 | 198 | 2 |

| Which of the following are symptoms of pubic lice (crab lice)? | |||

| 12. Pink rash all over body | 307 | 472 | 4 |

| 13. Itching in affected areas | 763 | 15 | 4 |

| 14. Tiny purplish spots in the affected area | 598 | 199 | 4 |

| 15. Fever | 254 | 523 | 5 |

| 16. Swollen genitals | 524 | 255 | 3 |

| 17. Discharge (fluid) from the vagina or penis | 387 | 392 | 3 |

| 18. Visualizing lice in the pubic hair | 658 | 120 | 4 |

| 19. Evidence of lice eggs on pubic hair | 702 | 76 | 4 |

| If you become infected with pubic lice, what actions should you take in addition to seeking assistance from a health care provider? | |||

| 20. Bathe in Lysol or bleach water | 213 | 566 | 3 |

| 21. Use hydrocortisone on bites | 634 | 143 | 5 |

| 22. Take antibiotics | 623 | 152 | 7 |

| 23. Use pesticide containing creme | 485 | 290 | 7 |

| 24. Discontinue contact with current intimate partner, and inform them of lice | 731 | 45 | 6 |

| 25. Have you ever had pubic lice (crab lice)? | 16 | 760 | 6 |

| 26. Have you ever had any other sexually transmitted disease? | 32 | 750 | 1 |

Share and Cite

Anderson, A.L.; Chaney, E. Pubic Lice (Pthirus pubis): History, Biology and Treatment vs. Knowledge and Beliefs of US College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 592-600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020592

Anderson AL, Chaney E. Pubic Lice (Pthirus pubis): History, Biology and Treatment vs. Knowledge and Beliefs of US College Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009; 6(2):592-600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020592

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Alice L., and Elizabeth Chaney. 2009. "Pubic Lice (Pthirus pubis): History, Biology and Treatment vs. Knowledge and Beliefs of US College Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 6, no. 2: 592-600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020592

APA StyleAnderson, A. L., & Chaney, E. (2009). Pubic Lice (Pthirus pubis): History, Biology and Treatment vs. Knowledge and Beliefs of US College Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(2), 592-600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020592