Teleoncology: A Solution for Everyone? A Single-Center Experience with Telemedicine during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Comprehending patient satisfaction with the telehealth visit during this period and finding differences between patient groups.

- Knowing patient preferences on telemedicine use and identifying the within-group differences.

- Analyzing the technological skills of our study population and its possible influence on patient preferences towards telemedicine.

2. Materials and Methods

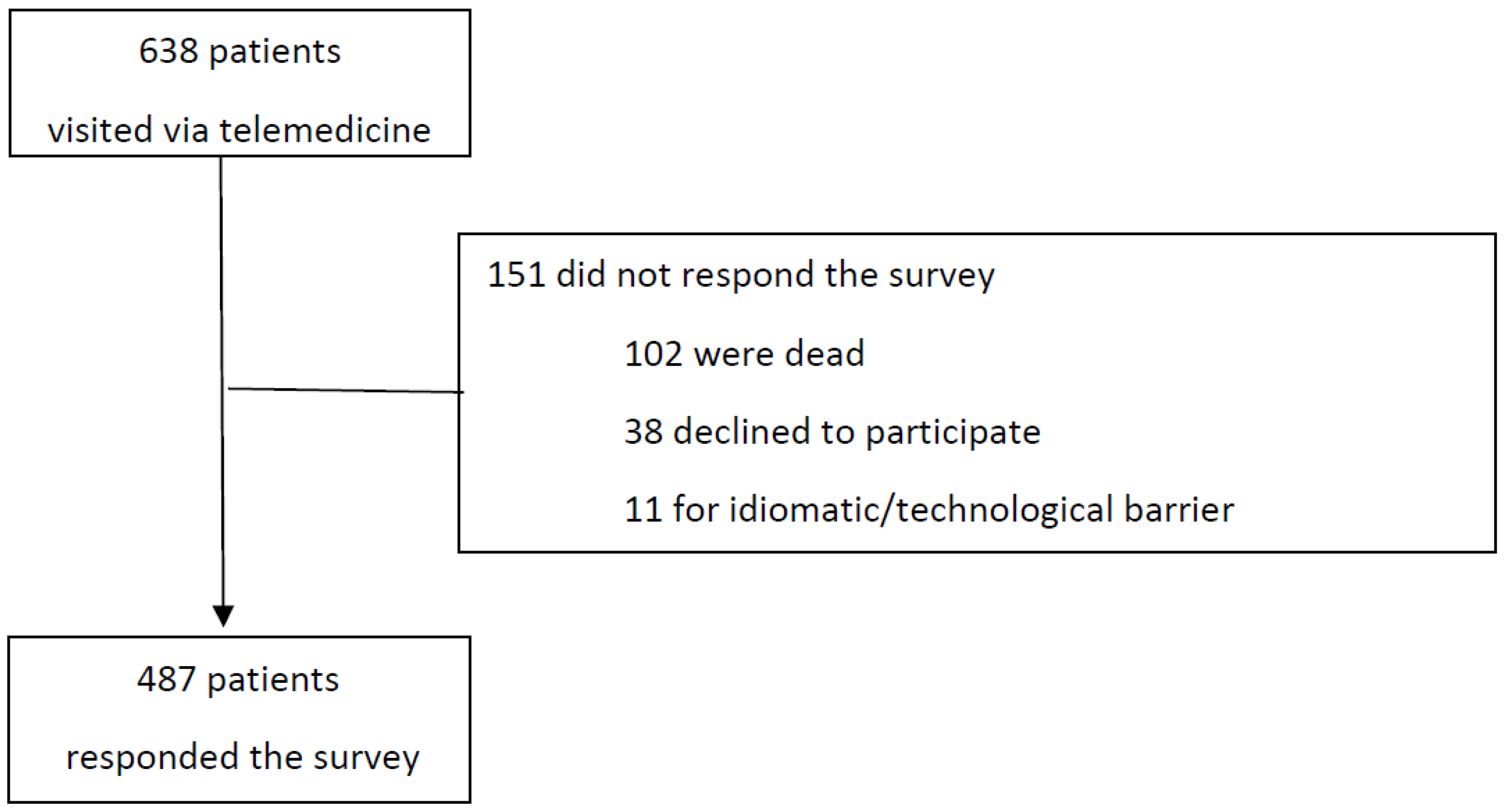

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Survey

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Satisfaction with the Use of Telemedicine

3.2. Patient Preferences towards Telemedicine and Future Perspectives

3.3. Patients’ Knowledge of New Technologies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Alhazzani, W.; Alhuraiji, A.; Coomes, E.A.; Chemaly, R.F.; Almuhanna, M.; Wolff, R.A.; Ibrahim, N.K.; Chua, M.L.K.; Hotte, S.J.; et al. A Practical Approach to the Management of Cancer Patients During the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: An International Collaborative Group. Oncologist 2020, 25, e936–e945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, J.; Ouyang, W.; Chua, M.L.K.; Xie, C. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Patients With Cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, W.; Guan, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Xu, K.; Li, C.; Ai, Q.; Lu, W.; Liang, H.; et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Gupta, R.; Advani, S.; Ouellette, L.; Kuderer, N.M.; Lyman, G.H.; Li, A. Mortality in hospitalized patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer 2021, 127, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curigliano, G.; Banerjee, S.; Cervantes, A.; Garassino, M.C.; Garrido, P.; Girard, N.; Haanen, J.; Jordan, K.; Lordick, F.; Machiels, J.P.; et al. Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: An ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1320–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zon, R.T.; Kennedy, E.B.; Adelson, K.; Blau, S.; Dickson, N.; Gill, D.; Laferriere, N.; Lopez, A.M.; Mulvey, T.M.; Patt, D.; et al. Telehealth in Oncology: ASCO Standards and Practice Recommendations. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, 546–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine: Opportunities and Developments in Member States: Report on the Second Global Survey on eHealth; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sirintrapun, S.J.; Lopez, A.M. Telemedicine in Cancer Care. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, 38, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoed, S.; Breen, S.; Gough, K.; Aranda, S. Benefits of remote real-time side-effect monitoring systems for patients receiving cancer treatment. Oncol. Rev. 2012, 6, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, A.; Lucas, G.; Marcu, A.; Piano, M.; Grosvenor, W.; Mold, F.; Maguire, R.; Ream, E. Cancer Survivors’ Experience With Telehealth: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brunello, A.; Galiano, A.; Finotto, S.; Monfardini, S.; Colloca, G.; Balducci, L.; Zagonel, V. Older cancer patients and COVID-19 outbreak: Practical considerations and recommendations. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 9193–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, D.; Larkins, S.; Kelly, J.; Sabesan, S. Remote chemotherapy supervision model for rural cancer care: Perspectives of health professionals. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worster, B.; Swartz, K. Telemedicine and Palliative Care: An Increasing Role in Supportive Oncology. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirke, M.M.; Shaikh, S.A.; Harky, A. Tele-oncology in the COVID-19 Era: The Way Forward? Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, C.; Zurawel-Balaura, L.; Wong, R.K. How effective is video consultation in clinical oncology? A systematic review. Curr. Oncol. 2010, 17, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doolittle, G.C.; Spaulding, A.O.; Williams, A.R. The decreasing cost of telemedicine and telehealth. Telemed. J. E Health 2011, 17, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.M.; Chu, C.K.; Liu, J.; Angove, R.; Rocque, G.; Gallagher, K.D.; Momoh, A.O.; Caston, N.E.; Williams, C.P.; Wheeler, S.; et al. Determinants of telemedicine adoption among financially distressed patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from a nationwide study. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7665–7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, J.F.; Beard, M.; Kumar, S. Systematic review of patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients’ health. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marzorati, C.; Renzi, C.; Russell-Edu, S.W.; Pravettoni, G. Telemedicine Use Among Caregivers of Cancer Patients: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, K.A.; Rood, M.; Jhangiani, N.; Kou, L.; Rose, S.; Boissy, A.; Rothberg, M.B. Patterns of Use and Correlates of Patient Satisfaction with a Large Nationwide Direct to Consumer Telemedicine Service. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1768–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koonin, L.M.; Hoots, B.; Tsang, C.A.; Leroy, Z.; Farris, K.; Jolly, B.; Antall, P.; McCabe, B.; Zelis, C.B.R.; Tong, I.; et al. Trends in the Use of Telehealth During the Emergence of the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, January–March 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onesti, C.E.; Rugo, H.S.; Generali, D.; Peeters, M.; Zaman, K.; Wildiers, H.; Harbeck, N.; Martin, M.; Cristofanilli, M.; Cortes, J.; et al. Oncological care organisation during COVID-19 outbreak. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Sundaresan, T.; Reed, M.E.; Trosman, J.R.; Weldon, C.B.; Kolevska, T. Telehealth in Oncology During the COVID-19 Outbreak: Bringing the House Call Back Virtually. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabesan, S. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Teleoncology: Clinical Oncological Society of Australia. Available online: https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/COSA:Teleoncology (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Fraser, A.; McNeill, R.; Robinson, J. Cancer care in a time of COVID: Lung cancer patient’s experience of telehealth and connectedness. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, H.M.; Smrke, A.; Cowie, F.; White, J.; Chong, P.; Lo, S.; Mahendra, A.; Gupta, S.; Ferguson, M.; Boddie, D.; et al. What Matters to Us: Impact of Telemedicine During the Pandemic in the Care of Patients With Sarcoma Across Scotland. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Lee, S.W.; Devarakonda, A.K.; Arora, T.K. Patient and Physician Attitudes Toward Telemedicine in Cancer Clinics Following the COVID-19 Pandemic. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2021, 5, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Lindgren, B.R.; Blaes, A.H.; Parsons, H.M.; Larocca, C.J.; Farah, R.; Hui, J.Y.C. The New Normal? Patient Satisfaction and Usability of Telemedicine in Breast Cancer Care. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5668–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrke, A.; Younger, E.; Wilson, R.; Husson, O.; Farag, S.; Merry, E.; Macklin-Doherty, A.; Cojocaru, E.; Arthur, A.; Benson, C.; et al. Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Care for Rare Cancers. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.S.; Seidman, D.; Berger, N.; Cascetta, K.P.; Nezolosky, M.; Trlica, K.; Ryncarz, A.; Keeton, C.; Moshier, E.; Tiersten, A. Patient Perception of Telehealth Services for Breast and Gynecologic Oncology Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Single Center Survey-based Study. J. Breast Cancer 2020, 23, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; Hockings, H.; Lapuente, M.; Adeniran, P.; Saud, R.A.; Sivajothi, A.; Amin, J.; Crusz, S.M.; Rashid, S.; Szabados, B.; et al. Learning from Crisis: A Multicentre Study of Oncology Telemedicine Clinics Introduced During COVID-19. J. Cancer Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loree, J.M.; Dau, H.; Rebić, N.; Howren, A.; Gastonguay, L.; McTaggart-Cowan, H.; Gill, S.; Raghav, K.; De Vera, M.A. Virtual Oncology Appointments during the Initial Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Survey of Patient Perspectives. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Joode, K.; Dumoulin, D.W.; Engelen, V.; Bloemendal, H.J.; Verheij, M.; Van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Dingemans, I.H.; Dingemans, A.C.; Van Der Veldt, A.A.M. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on cancer treatment: The patients’ perspective. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 136, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondal, H.; Abbas, T.; Choquette, H.; Le, D.; Chalchal, H.I.; Iqbal, N.; Ahmed, S. Patient and Physician Satisfaction with Telemedicine in Cancer Care in Saskatchewan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3870–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paige, S.R.; Campbell-Salome, G.; Alpert, J.; Markham, M.J.; Murphy, M.; Heffron, E.; Harle, C.; Yue, S.; Xue, W.; Bylund, C.L. Cancer patients’ satisfaction with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, E.J.; Nicosia, B.; Shalowitz, D.I. A qualitative study of patients’ attitudes towards telemedicine for gynecologic cancer care. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 165, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, S.P.; Waissengrin, B.; Shachar, E.; Hodruj, M.; Fayngor, R.; Brezis, M.; Nikolaevski-Berlin, A.; Pelles, S.; Safra, T.; Geva, R.; et al. Rapid Implementation of Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perspectives and Preferences of Patients with Cancer. Oncologist 2021, 26, e679–e685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Coluccia, S.; Grizzuti, M.; Romano, M.C.; Esposito, G.; Crispo, A.; Cuomo, A. Satisfaction with Telemedicine for Cancer Pain Management: A Model of Care and Cross-Sectional Patient Satisfaction Study. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 5566–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, N.; Demeco, A.; Moggio, L.; Ammendolia, A. Why is telerehabilitation necessary? A pre-post COVID-19 comparative study of ICF activity and participation. J. Enabling Technol. 2021, 15, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lalla, V.; Patrick, H.; Siriani-Ayoub, N.; Kildea, J.; Hijal, T.; Alfieri, J. Satisfaction among Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiotherapy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Institutional Experience. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granberg, R.E.; Heyer, A.; Rising, K.L.; Handley, N.R.; Gentsch, A.T.; Binder, A.F. Medical Oncology Patient Perceptions of Telehealth Video Visits. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, e1333–e1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaverdian, N.; Gillespie, E.F.; Cha, E.; Kim, S.Y.; Benvengo, S.; Chino, F.; Kang, J.J.; Li, Y.; Atkinson, T.M.; Lee, N.; et al. Impact of Telemedicine on Patient Satisfaction and Perceptions of Care Quality in Radiation Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Guan, B.S.; Li, Z.K.; Li, X.Y. Effect of telehealth intervention on breast cancer patients’ quality of life and psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodaveisi, T.; Sadoughi, F.; Novin, K.; Hosseiniravandi, M.; Dehnad, A. Development and evaluation of a teleoncology system for breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizot, A.; Karimi, M.; Rassy, E.; Heudel, P.E.; Levy, C.; Vanlemmens, L.; Uzan, C.; Deluche, E.; Genet, D.; Saghatchian, M.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of breast cancer patients’ satisfaction and experience with oncology telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadili, L.; DeGirolamo, K.; Ma, C.S.; Chen, L.; McKevitt, E.; Pao, J.S.; Dingee, C.; Bazzarelli, A.; Warburton, R. The Breast Cancer Patient Experience of Telemedicine During COVID-19. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 2244–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miziara, R.A.; Maesaka, J.Y.; Matsumoto, D.R.M.; Penteado, L.; Anacleto, A.; Accorsi, T.A.D.; Lima, K.A.; Cordioli, E.; GS, D.A. Teleoncology Orientation of Low-Income Breast Cancer Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Feasibility and Patient Satisfaction. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2021, 43, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, E.; Qiu, J.; Zafar, A.; Tramontano, A.C.; Isakoff, S.; Winer, E.; Schrag, D.; Manz, C. Breast Medical Oncologists’ Perspectives of Telemedicine for Breast Cancer Care: A Survey Study. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, e1447–e1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrowder, D.A.; Miller, F.G.; Vaz, K.; Anderson Cross, M.; Anderson-Jackson, L.; Bryan, S.; Latore, L.; Thompson, R.; Lowe, D.; McFarlane, S.R.; et al. The Utilization and Benefits of Telehealth Services by Health Care Professionals Managing Breast Cancer Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, F.; Oksuzoglu, B. Teleoncology or telemedicine for oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: The new normal for breast cancer survivors? Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 2191–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.; Lu, A.D.; Shi, Y.; Covinsky, K.E. Assessing Telemedicine Unreadiness Among Older Adults in the United States During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogland, A.I.; Mansfield, J.; Lafranchise, E.A.; Bulls, H.W.; Johnstone, P.A.; Jim, H.S.L. eHealth literacy in older adults with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2020, 11, 1020–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.J.; Crichton, M.; Crawford-Williams, F.; Agbejule, O.A.; Yu, K.; Hart, N.H.; De Abreu Alves, F.; Ashbury, F.D.; Eng, L.; Fitch, M.; et al. The efficacy, challenges, and facilitators of telemedicine in post-treatment cancer survivorship care: An overview of systematic reviews. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1552–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Respondents n = 487 (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age groups | |

| ≤50 years | 53 (10.9) |

| 51–69 years | 224 (46) |

| ≥70 years | 210 (43.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 218 (44.8) |

| Female | 269 (55.2) |

| ECOG | |

| 0 | 384 (78.9) |

| 1 | 99 (20.3) |

| ≥2 | 4 (0.8) |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| Colorectal | 210 (43.1) |

| GI non-colorectal | 41 (8.4) |

| Thoracic | 29 (6) |

| Breast | 129 (26.5) |

| Others (GIST, melanoma, TNE) | 78 (16) |

| Clinical stage | |

| I | 99 (20.3) |

| II | 124 (25.5) |

| III | 172 (35.3) |

| IV | 92 (18.9) |

| Type of visit | |

| Surveillance | 320 (65.7) |

| Treatment | 167 (34.3) |

| Oncological treatment | |

| No treatment | 320 (65.7) |

| Adjuvant | 103 (21.1) |

| Neoadjuvant | 13 (2.7) |

| Palliative | 51 (10.5) |

| Route of administration | |

| No treatment | 320 (65.7) |

| Intravenous | 61 (12.5) |

| Oral | 96 (19.8) |

| Others (subcutaneous, intramuscular) | 10 (2.1) |

| Drug type | |

| No treatment | 320 (65.7) |

| Targeted therapy | 25 (5.1) |

| Hormonotherapy | 80 (16.4) |

| Immunotherapy | 24 (4.9) |

| Chemotherapy | 38 (7.8) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribera, P.; Soriano, S.; Climent, C.; Vilà, L.; Macias, I.; Fernández-Morales, L.A.; Giner, J.; Gallardo, E.; Palmer, M.A.S.; Pericay, C. Teleoncology: A Solution for Everyone? A Single-Center Experience with Telemedicine during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8565-8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110675

Ribera P, Soriano S, Climent C, Vilà L, Macias I, Fernández-Morales LA, Giner J, Gallardo E, Palmer MAS, Pericay C. Teleoncology: A Solution for Everyone? A Single-Center Experience with Telemedicine during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(11):8565-8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110675

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibera, Paula, Sandra Soriano, Carla Climent, Laia Vilà, Ismael Macias, Luis Antonio Fernández-Morales, Julia Giner, Enrique Gallardo, Miquel Angel Segui Palmer, and Carles Pericay. 2022. "Teleoncology: A Solution for Everyone? A Single-Center Experience with Telemedicine during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic" Current Oncology 29, no. 11: 8565-8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110675

APA StyleRibera, P., Soriano, S., Climent, C., Vilà, L., Macias, I., Fernández-Morales, L. A., Giner, J., Gallardo, E., Palmer, M. A. S., & Pericay, C. (2022). Teleoncology: A Solution for Everyone? A Single-Center Experience with Telemedicine during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Current Oncology, 29(11), 8565-8578. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110675