Perspective on Cancer Control: Whither the Tobacco Endgame for Canada?

Abstract

:1. Introduction: The Start of the Tobacco Endgame Discussion in Canada

2. After the Summit—What Has Been Achieved in Canada?

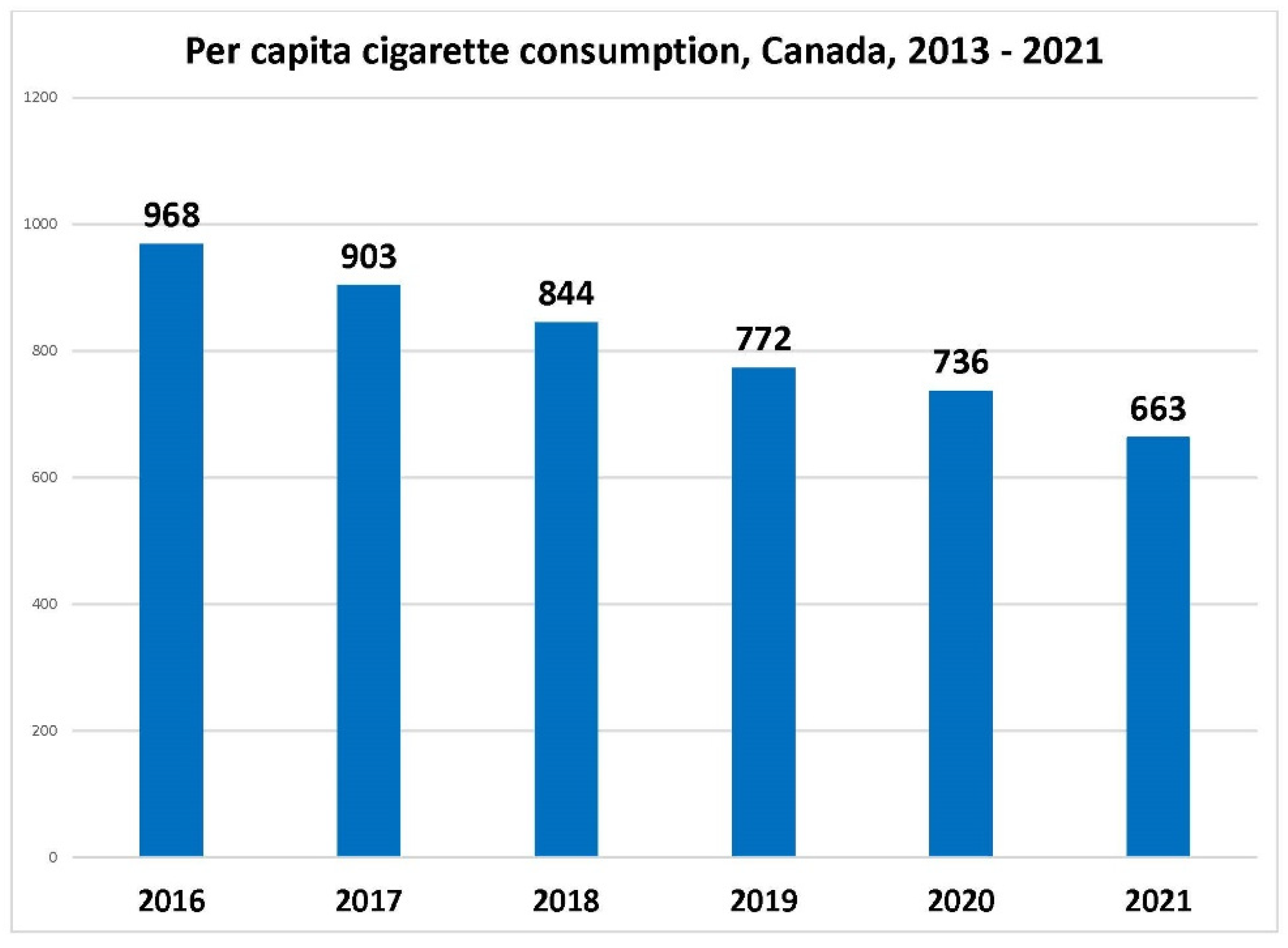

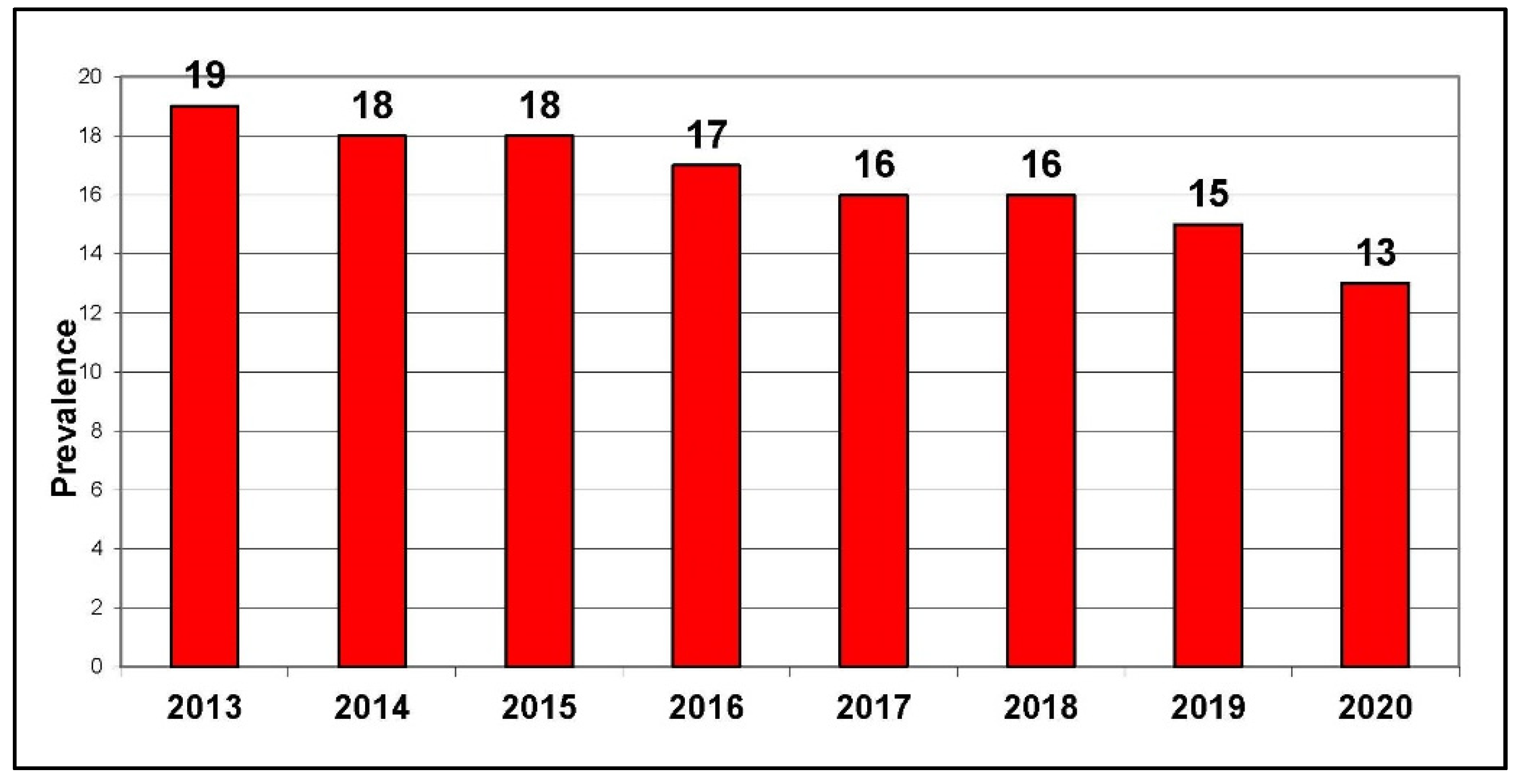

2.1. Changes in Population Tobacco and Nicotine Behaviours since 2016

2.2. Tobacco Control Policy Changes since the Summit

2.2.1. Taxation and Price

2.2.2. Retail Packaging and Product

2.2.3. Flavoured Tobacco

2.2.4. Restrictions on Smoking

2.2.5. Restrictions on Sales and Promotions

2.2.6. Manufacturer Cost Recovery Fee

2.2.7. Health Warnings

2.2.8. E-Cigarettes

2.2.9. Litigation against the Tobacco Industry

2.3. A Reality Check—Is “<5 by ’35” Achievable?

2.4. Endgame Developments Globally

- -

- Linking approaches to tobacco control to broader objectives such as tackling health inequities;

- -

- Substantial strengthening of supply measures, such as dramatically reducing the number of tobacco retailers and more substantial regulation of the industry itself.

Product Regulation Changes Designed to Reduce Appeal and Addictiveness of Tobacco Products

3. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Popova, S.; Patra, J.; Rehm, J. Avoidable portion of tobacco-attributable acute care hospital days and its cost due to implementation of different intervention strategies in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 2179–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey, 2014. Cansim Table 105-0501. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310045101 (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Zhang, B.; Schwartz, R.; Technical Report of the Ontario SimSmoke: The Effect of Tobacco Control Strategies and Interventions on Smoking Prevalence and Tobacco Attributable Deaths in Ontario, Canada. OTRU. 2013. Available online: https://otru.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/special_simsmoke.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Malone, R.E. Tobacco endgames: What they are and are not, issues for tobacco control strategic planning and a possible US scenario. Tob. Control 2013, 22, i42–i44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey, Table 13-10-0096-10 Smokers, by Age Group. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009610 (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey.html (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Chaiton, M.; Dubray, J.; Guindon, G.E.; Schwartz, R. Tobacco Endgame Simulation Modelling: Assessing the Impact of Policy Changes on Smoking Prevalence in 2035. Forecasting 2021, 3, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Tobacco Products Regulations: Plain and Standardized Appearance—Facts about Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco/legislation/federal-regulations/products-regulations-plain-standardized-appearance/facts.html (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Government of Canada. Order Amending the Schedule to the Tobacco Act (Menthol) P.C. 2017-256. 24 March 2017. Available online: https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2017/2017-04-05/html/sor-dors45-eng.html (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Government of Canada. Tobacco and Vaping Products Act. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/tobacco/legislation/federal-laws/tobacco-act.html (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health. Statement from the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health on Nicotine Vaping in Canada. 22 January 2020. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2020/01/statement-from-the-council-of-chief-medical-officers-of-health-on-nicotine-vaping-in-canada.html (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Collishaw, N. Calling the tobacco industry to account in Quebec. BMJ 2019, 365, l1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada. Targeting High Prevalence Populations. 28 November 2021. Available online: https://smoke-free-canada.blogspot.com/2021/11/the-smokers-who-are-inside-and-outside.html (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- O’Brien, D.; Long, J.; Quigley, J.; Lee, C.; McCarthy, A.; Kavanagh, P. Association between electronic cigarette use and tobacco cigarette smoking initiation in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, L.; Schwartz, R. Is “less than 5 by 35” still achievable? Health Promot. Chronic. Dis. Prev. Can. 2021, 41, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravely, S.; Giovino, G.A.; Craig, L.; Commar, A.; d’Espaignet, E.T.; Schotte, K.; Fong, G.T. Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: An association study. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e166–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Decision FCTC/COP8(16): Measures to Strengthen Implementation of the Convention through Coordination and Cooperation. Decision Adopted by the WHO FCTC COP at Its 8th Session. 6 October 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/fctc/cop/sessions/cop8/FCTC_COP8(16).pdf.17 (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Timberlake, D.S.; Laitinen, U.; Kinnunen, J.M.; Rimpela, A.H. Strategies and barriers to achieving the goal of Finland’s tobacco endgame. Tob. Control 2020, 29, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. 2021; Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan. December 2021 Wellington: Ministry of Health. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/hp7801_-_smoke_free_action_plan_v15_web.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2022).

| 1. Product Changes—Less Addictive, Less Appealing |

| 2. Aligning tobacco supply withpublic health goals— change tobacco supply parameters: taxation price controls reduce retail availability |

| 3. Prevent new generation of smokers |

| 4. Transform access to cessation—no smoker left behind |

| Province or Territory | Provincial/Territorial Tax Increase | Average Manufacturing Price Increase * | Federal Tax Increase | Subtotal | Federal/Provincial/ Territorial Sales Tax Rate | Sales Tax | Total Government Tax Increases | Total Tax and Price Increases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YT | 20.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 51.25 | 5% | 2.56 | 30.61 | 53.81 |

| NWT | 3.60 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 34.85 | 5% | 1.74 | 13.39 | 36.59 |

| NU | 10.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 41.25 | 5% | 2.06 | 20.11 | 43.31 |

| BC | 14.40 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 45.65 | 5% | 2.28 | 24.73 | 47.93 |

| AB | 15.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 46.25 | 5% | 2.31 | 25.36 | 48.56 |

| SK | 4.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 35.25 | 11% | 3.88 | 15.93 | 39.13 |

| MB | 1.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 32.25 | 12% | 3.87 | 12.92 | 36.12 |

| ON | 12.25 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 43.50 | 13% | 5.66 | 25.96 | 49.16 |

| QC | 4.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 35.25 | 5% | 1.76 | 13.81 | 37.01 |

| NB | 13.04 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 44.29 | 15% | 6.64 | 27.73 | 50.93 |

| NS | 12.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 43.25 | 15% | 6.49 | 26.54 | 49.74 |

| PEI | 10.04 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 41.29 | 15% | 6.19 | 24.28 | 47.48 |

| NL | 18.00 | 23.20 | 8.05 | 49.25 | 15% | 7.39 | 33.44 | 56.64 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eisenhauer, E.A.; Schwartz, R.; Cunningham, R.; Hagen, L.; Fong, G.T.; Callard, C.; Chaiton, M.; Pipe, A. Perspective on Cancer Control: Whither the Tobacco Endgame for Canada? Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 2081-2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29030168

Eisenhauer EA, Schwartz R, Cunningham R, Hagen L, Fong GT, Callard C, Chaiton M, Pipe A. Perspective on Cancer Control: Whither the Tobacco Endgame for Canada? Current Oncology. 2022; 29(3):2081-2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29030168

Chicago/Turabian StyleEisenhauer, Elizabeth A., Robert Schwartz, Rob Cunningham, Les Hagen, Geoffrey T. Fong, Cynthia Callard, Michael Chaiton, and Andrew Pipe. 2022. "Perspective on Cancer Control: Whither the Tobacco Endgame for Canada?" Current Oncology 29, no. 3: 2081-2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29030168

APA StyleEisenhauer, E. A., Schwartz, R., Cunningham, R., Hagen, L., Fong, G. T., Callard, C., Chaiton, M., & Pipe, A. (2022). Perspective on Cancer Control: Whither the Tobacco Endgame for Canada? Current Oncology, 29(3), 2081-2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29030168