Setting Priorities for a Provincial Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Program Components

2.3. Participant Identification and In-Person Session Format

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Characteristics

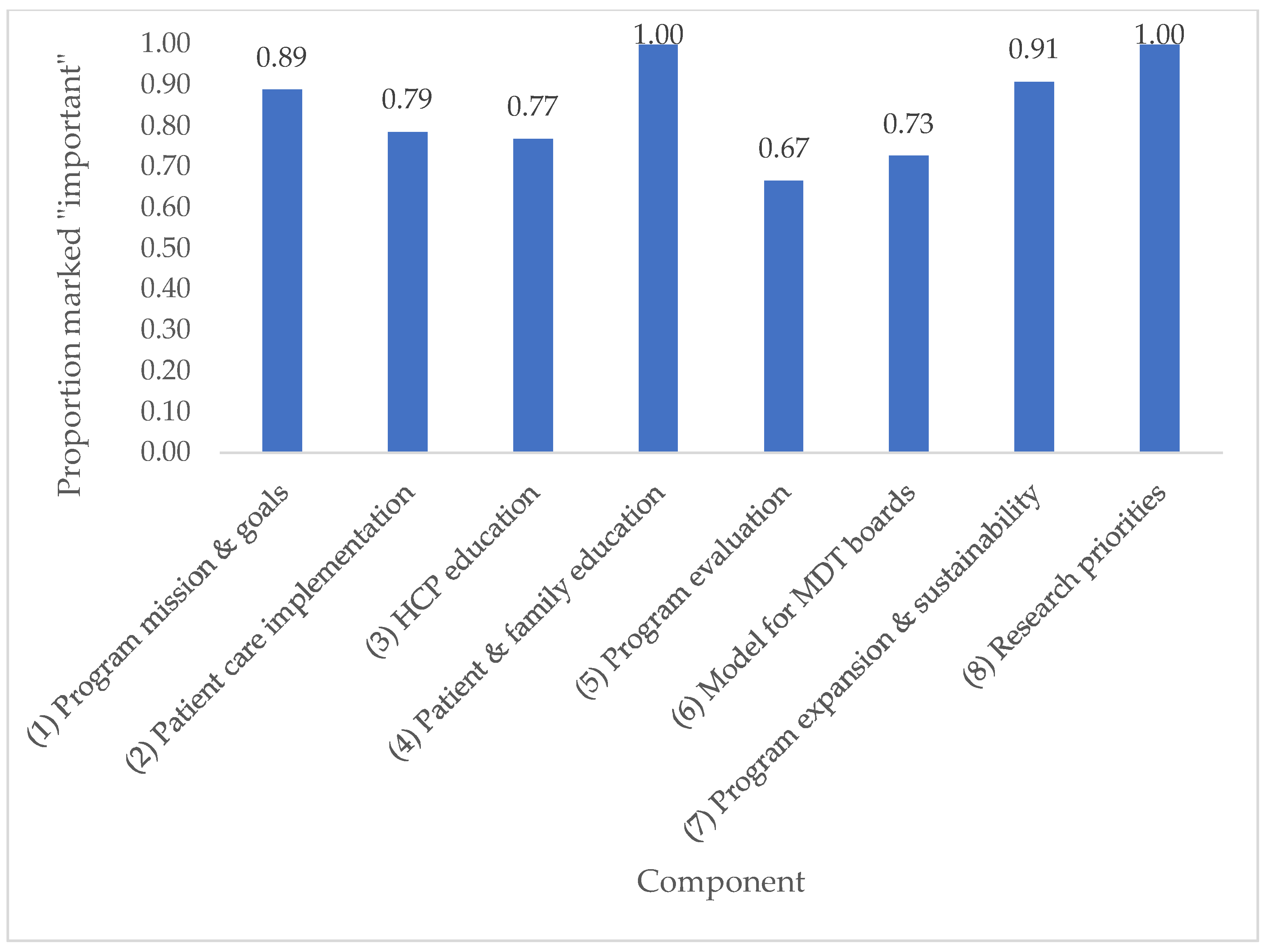

3.2. Delphi Survey and Round Table Discussion Results

3.2.1. Scope of Program

3.2.2. Psychosocial Services

3.2.3. Care Pathways

3.2.4. Role of AYA Team

3.2.5. Health Care Provider Education Delivery

3.2.6. Priorities for Education

3.2.7. Patients and Family Engagement

3.2.8. Program Expansion and Sustainability

3.2.9. Implementation Prioritization

3.2.10. Potential Program Tasks

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area of Work | Responses (n) | % | Participants (n) | % |

| Administration | 4 | 6.7% | 1 | 3.7% |

| Oncology | 16 | 26.7% | 10 | 37.0% |

| Nursing | 16 | 26.7% | 4 | 14.8% |

| Psychosocial and Therapeutic Services | 13 | 21.7% | 5 | 18.5% |

| Radiation Therapy | 1 | 1.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Pain and Symptom Management | 4 | 6.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Nutrition | 1 | 1.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Patient/Caregiver Advisor | 1 | 1.7% | 3 | 11.1% |

| Psychiatry | 1 | 1.7% | 1 | 3.7% |

| Nurse Practitioner | 1 | 1.7% | 1 | 3.7% |

| Speech Language Pathology | 1 | 1.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Vocational Rehabilitation | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3.7% |

| Other—Patient Advocate | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3.7% |

| No Response | 1 | 1.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 60 | 100% | 27 | 100% |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Discussion Guides

| Program Mission and Goals—Discussion Guide |

Program mission: Create a provincial interdisciplinary cancer program for adolescents and young adults aged 15–29 years that will regionally implement recommendations across all BC Cancer sites in partnership with BC Children’s Hospital

|

| Patient Care Implementation—Discussion Guide |

|

| Health Care Provider Education—Discussion Guide |

|

| Program Evaluation Strategy—Discussion Guide |

|

| Patient and Family Education and Engagement—Discussion Guide |

|

| Program Expansion and Sustainability—Discussion Guide |

|

Appendix B.2. Delphi Survey Results Summary

| Item | Round 1 Weighted Mean | Round 2 Weighted Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Program Mission and Goals | ||

| Program mission: Create a provincial interdisciplinary cancer program for adolescents and young adults aged 15–29 years that will regionally implement recommendations across all BC Cancer sites in partnership with BCCH | 4.61 | - |

| Goal 1: Develop health care provider education curriculum based on a formal learning needs assessment with clinical teams | 4.08 | - |

| Goal 2: Facilitate clinical consults with referral pathways to other services and flexible access to interventions | 4.45 | - |

| Goal 3: Integrate access to AYA-specific psychosocial distress screening and fertility preservation screening and referral | 4.41 | - |

| Goal 4: Develop multidisciplinary tumor board case reviews supported at BCCH and BC Cancer | 3.78 | 4.04 |

| Goal 5: Create evidence-based quality improvement and program evaluation plans | 4.02 | - |

| Goal 6: Develop a comprehensive AYA research program | 3.83 | 3.81 |

| Goal 7: Introduce patient reported outcome measurement to improve patient experience | 4.18 | - |

| Goal 8: Support patients and families through education and peer support network | 4.43 | - |

| Patient Care Implementation | ||

| Develop referral pathways for patients referred to BC Cancer, BCCH, VGH based on age and diagnosis | 4.66 | - |

| Ensure all AYA patients screened for distress at intake | 4.53 | - |

| Create process so all AYA patients offered AYA program consultation with advanced practice nurse (APN) and counselor | 4.64 | - |

| Create process so all AYA patients offered follow-up with APN or counselor during treatment trajectory | 4.57 | - |

| Create process so all AYA patients routinely contacted at pre-specified times during care trajectory for follow-up of clinical issues | 4.30 | - |

| AYA APN and/or counselor to see patients referred into the program only (referral-based program) | 3.98 | 3.91 |

| AYA APN and/or counselor meet with all AYA patients at least once after new patient intake appointment | 4.38 | - |

| AYA APN and counselor to work out of a dedicated space separate from current oncology clinics | 3.15 | 3.70 |

| AYA APN and counselor to see patients during pre-existing oncology clinic appointments | 3.79 | 3.96 |

| Develop/adapt and implement AYA-specific screening tools (psychological distress, fertility screening) | 4.33 | - |

| Establish referral pathways for pre-defined high problem issues (such as suicide, psychosocial distress, fertility preservation, urgent end of life symptom management) | 4.67 | - |

| Establish transition pathways between BCCH, BC Cancer, and VGH | 4.45 | - |

| Develop/adapt tumor-specific treatment guidelines | 4.05 | - |

| Develop/adapt AYA-specific supportive care guidelines | 4.35 | - |

| Health Care Provider Education Strategy | ||

| Conduct health care provider (HCP) education needs assessment through surveys of nursing, counseling, and physicians at BCCH and BC Cancer asking respondents to rank education priorities | 3.98 | 3.79 |

| Conduct education needs assessment among GPOs via survey asking respondents to rank education priorities | 3.23 | 4.04 |

| Conduct education needs assessment among primary care providers via survey asking respondents to rank education priorities | 3.88 | |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: fertility preservation and counseling | 4.40 | - |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: survivorship and late effects for AYA | 4.44 | - |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: the unique psychosocial needs of AYA | 4.53 | - |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: navigating interpersonal relationships for patients in treatment | 4.38 | - |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: palliative care needs for AYA | 4.47 | - |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: coaching lifestyle changes, healthy diet, and exercise for AYA patients on treatment | 4.20 | - |

| Development of online continuing medical education accredited module in AYA oncology targeted to all health care providers involved in AYA care | 3.91 | 4.13 |

| Development of AYA fellowship program with Royal College diploma for Focused Competency in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology | 3.80 | 3.67 |

| Annual grand rounds on AYA oncology | 3.65 | 4.42 |

| Establish formal partnerships between various organizations for ongoing HCP education (i.e., Family Practice Oncology Network, Community Oncology Network sites) | 3.96 | 4.09 |

| Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy | ||

| Conduct environmental scan to determine top educational needs of AYA patients and families | 4.38 | - |

| Conduct environmental scan to identify existing AYA patient and family education resources to be adapted to BC context | 4.05 | - |

| Gather BC Cancer and BCCH new patient materials to adapt to AYA needs | 4.06 | - |

| Develop patient education materials on fertility preservation and counseling | 4.48 | - |

| Develop patient education materials on survivorship and late effects for AYA | 4.50 | - |

| Develop patient education materials on healthy lifestyle including nutrition and exercise | 4.24 | - |

| Develop an AYA peer support network | 4.30 | - |

| Develop a long-term patient and family engagement strategy for ongoing feedback into program development | 4.14 | - |

| Program Evaluation Strategy | ||

| Ensure collection of adequate baseline outputs and outcomes prior to program implementation | 4.00 | - |

| Identify opportunities for data collection within existing resources | 4.00 | - |

| Identify additional resources required (including staff) for ongoing data collection | 3.95 | 4.23 |

| Establish frequency of data collection and frequency of review by oversight committee | 3.85 | 3.73 |

| Establish outputs and outcomes of relevance for data collection | 4.24 | - |

| Determine how evaluation updates will be shared with patients, family, and senior leadership on a regular basis | 3.86 | 3.82 |

| Model for Multidisciplinary Conference (MDC) Tumor Board Review | ||

| Identify required team members for tumor board attendance and optional attendees | 3.79 | 4.05 |

| Representatives from medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery/surgical oncology, pathology, diagnostic radiology, nursing, and patient and family counseling should be present to provide the complete range of expert opinion appropriate for the disease site and appropriate for the hospital | 4.45 | - |

| Representatives for BCCH and BC Cancer oncology services will attend conference | 4.23 | - |

| Establish ideal frequency, date, and timing of tumor boards and how notification will be undertaken—MDC should occur for a minimum of 1 h every 2 weeks | 3.82 | 3.89 |

| Identify electronic/online tumor board opportunities and platforms | 4.21 | - |

| All new AYA patient treatment plans should be forwarded to AYA MDC coordinator | 4.04 | - |

| Not all cases forwarded to the MDC coordinator need to be discussed at the AYA MDC | 3.82 | 3.80 |

| The individual physician and the MDC chair can determine which cases are discussed in detail at the MDC | 3.94 | 4.15 |

| Other cases (e.g., recurrent or metastatic cancer) can be forwarded to the MDC coordinator for discussion, at the discretion of the individual physician | 3.89 | 3.80 |

| AYA MDC will primarily serve to identify all suitable treatment options, and ensure the most appropriate treatment recommendations are generated for each cancer patient discussed prospectively in a multidisciplinary forum | 4.43 | - |

| Secondary functions of AYA MDC will include: a forum for the continuing education of medical staff and health professionals, contributing to the development of standardized patient management protocols, and contributing to linkages among regions to ensure appropriate referrals and timely consultation | 4.22 | - |

| AYA Research Priorities | ||

| Form an AYA research and evaluation working group | 4.15 | - |

| Identify platforms for data collection | 4.05 | - |

| Develop and implement a program evaluation strategy through research | 4.00 | - |

| Identify patient reported outcomes and clinical outcomes for collection | 4.29 | - |

| Develop a quality improvement plan and strategy | 4.14 | - |

| Identify key stakeholders for AYA research | 4.00 | - |

| Identify and implement an AYA research agenda | 3.95 | 4.05 |

| Develop an AYA research education plan (e.g., fellowship training for HCPs) | 3.76 | 4.10 |

| Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability | ||

| Identify key clinical and operations stakeholders for ongoing expansion | 4.23 | - |

| Develop website content and create a program email address | 4.42 | - |

| Develop social media strategies | 4.00 | - |

| Foster and develop online platform and app development | 4.26 | - |

| Review different models of expansion (spoke and hub; health authority-specific champions) | 4.11 | - |

| Identify available resources for de-centralized telemedicine expansion capacity | 4.09 | - |

| Identify available resources (including HCP compensation) for physical expansion capacity | 4.13 | - |

| Identify and explore operations and infrastructure limitations to expanding AYA program | 3.84 | 4.38 |

| Identify BC Cancer Foundation long-term funding opportunities | 4.49 | - |

| Identify AYA “champions” in regional centers to for ongoing program development | 4.29 | - |

| Foster relationships with motivated survivors, patients, and families for ongoing advocacy | 4.56 | - |

Appendix C. All Items Rated Important across All Domains

| Program Item | Score | Component |

|---|---|---|

| Program mission: Create a provincial interdisciplinary cancer program for adolescents and young adults aged 15–29 years that will regionally implement recommendations across all BC Cancer sites in partnership with BCCH | 4.61 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Goal 1: Develop health care provider education curriculum based on a formal learning needs assessment with clinical teams | 4.08 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Goal 2: Facilitate clinical consults with referral pathways to other services and flexible access to interventions | 4.45 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Goal 3: Integrate access to AYA-specific psychosocial distress screening and fertility preservation screening and referral | 4.41 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Goal 4: Develop multidisciplinary tumor board case reviews supported at BCCH and BC Cancer | 4.04 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Goal 5: Create evidence-based quality improvement and program evaluation plans | 4.02 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Goal 7: Introduce patient reported outcome measurement to improve patient experience | 4.18 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Goal 8: Support patients and families through education and peer support network | 4.43 | Program Mission and Goals |

| Develop referral pathways for patients referred to BC Cancer, BCCH, VGH based on age and diagnosis | 4.66 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Ensure all AYA patients screened for distress at intake | 4.53 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Create process so all AYA patients offered AYA program consultation with advanced practice nurse (APN) and counselor | 4.64 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Create process so all AYA patients offered follow-up with APN or counselor during treatment trajectory | 4.57 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Create process so all AYA patients routinely contacted at pre-specified times during care trajectory for follow-up of clinical issues | 4.30 | Patient Care Implementation |

| AYA APN and/or counselor meet with all AYA patients at least once after new patient intake appointment | 4.38 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Develop/adapt and implement AYA-specific screening tools (psychological distress, fertility screening) | 4.33 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Establish referral pathways for pre-defined high problem issues (such as suicide, psychosocial distress, fertility preservation, urgent end of life symptom management) | 4.67 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Establish transition pathways between BCCH, BC Cancer, and VGH | 4.45 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Develop/adapt tumor-specific treatment guidelines | 4.05 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Develop/adapt AYA-specific supportive care guidelines | 4.35 | Patient Care Implementation |

| Conduct education needs assessment among GPOs via survey asking respondents to rank education priorities | 4.04 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: fertility preservation and counseling | 4.40 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: survivorship and late effects for AYA | 4.44 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: the unique psychosocial needs of AYA | 4.53 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: navigating interpersonal relationships for patients in treatment | 4.38 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: palliative care needs for AYA | 4.47 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| HCP needs assessment survey topic: coaching lifestyle changes, healthy diet, and exercise for AYA patients on treatment | 4.20 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| Development of online continuing medical education accredited module in AYA oncology targeted to all health care providers involved in AYA care | 4.13 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| Annual grand rounds on AYA oncology | 4.42 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| Establish formal partnerships between various organizations for ongoing HCP education (i.e., Family Practice Oncology Network, Community Oncology Network sites) | 4.09 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy |

| Conduct environmental scan to determine top educational needs of AYA patients and families | 4.38 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Conduct environmental scan to identify existing AYA patient and family education resources to be adapted to BC context | 4.05 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Gather BC Cancer and BCCH new patient materials to adapt to AYA needs | 4.06 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Develop patient education materials on fertility preservation and counseling | 4.48 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Develop patient education materials on survivorship and late effects for AYA | 4.50 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Develop patient education materials on healthy lifestyle including nutrition and exercise | 4.24 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Develop an AYA peer support network | 4.30 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Develop a long-term patient and family engagement strategy for ongoing feedback into program development | 4.14 | Patient and Family Education and Engagement Strategy |

| Ensure collection of adequate baseline outputs and outcomes prior to program implementation | 4.00 | Program Evaluation Strategy |

| Identify opportunities for data collection within existing resources | 4.00 | Program Evaluation Strategy |

| Identify additional resources required (including staff) for ongoing data collection | 4.23 | Program Evaluation Strategy |

| Establish outputs and outcomes of relevance for data collection | 4.24 | Program Evaluation Strategy |

| Identify required team members for tumor board attendance and optional attendees | 4.05 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| Representatives from medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery/surgical oncology, pathology, diagnostic radiology, nursing, and patient and family counseling should be present to provide the complete range of expert opinion appropriate for the disease site and appropriate for the hospital | 4.45 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| Representatives for BCCH and BC Cancer oncology services will attend conference | 4.23 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| Identify electronic/online tumor board opportunities and platforms | 4.21 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| All new AYA patient treatment plans should be forwarded to AYA MDC coordinator | 4.04 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| The individual physician and the MDC chair can determine which cases are discussed in detail at the MDC | 4.15 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| AYA MDC will primarily serve to identify all suitable treatment options, and ensure the most appropriate treatment recommendations are generated for each cancer patient discussed prospectively in a multidisciplinary forum | 4.43 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| Secondary functions of AYA MDC will include: a forum for the continuing education of medical staff and health professionals, contributing to the development of standardized patient management protocols, and contributing to linkages among regions to ensure appropriate referrals and timely consultation | 4.22 | MDC Tumor Board Review |

| Form an AYA research and evaluation working group | 4.15 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Identify platforms for data collection | 4.05 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Develop and implement a program evaluation strategy through research | 4.00 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Identify patient reported outcomes and clinical outcomes for collection | 4.29 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Develop a quality improvement plan and strategy | 4.14 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Identify key stakeholders for AYA research | 4.00 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Identify and implement an AYA research agenda | 4.05 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Develop an AYA research education plan (e.g., fellowship training for HCPs) | 4.10 | AYA Research Priorities |

| Identify key clinical and operations stakeholders for ongoing expansion | 4.23 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Develop website content and create a program email address | 4.42 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Develop social media strategies | 4.00 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Foster and develop online platform and app development | 4.26 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Review different models of expansion (spoke and hub; health authority-specific champions) | 4.11 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Identify available resources for de-centralized telemedicine expansion capacity | 4.09 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Identify available resources (including HCP compensation) for physical expansion capacity | 4.13 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Identify and explore operations and infrastructure limitations to expanding AYA program | 4.38 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Identify BC Cancer Foundation long-term funding opportunities | 4.49 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Identify AYA “champions” in regional centers to for ongoing program development | 4.29 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

| Foster relationships with motivated survivors, patients, and families for ongoing advocacy | 4.56 | Model for Program Expansion and Sustainability |

Appendix D. Agenda

- BC Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program

- Create the Program You Need

| Time | Item Number | Items |

|---|---|---|

| 8:30 a.m. | 1.0 | Registration, Coffee & Continental Breakfast |

| 9:00 a.m. | 2.0 | Welcome & Opening Remarks |

| 2.1 | A Family’s Experience with AYA Cancer Care | |

| 2.2 | Cancer Care for AYA in BC—Current Situation | |

| 2.3 | BC AYA Oncology Program—Program Development to Date | |

| 10:00 a.m. | 3.0 | Table Discussion & Report Back: Program Mission & Goals |

| 11:30 a.m. | -Lunch- | |

| 12:30 p.m. | 4.0 | Table Discussion & Report Back: Patient Care Implementation |

| 2:30 p.m. | -Break- | |

| 3:00 p.m. | 5.0 | Breakout Sessions |

| 5.1 | Health Care Provider Education Strategy | |

| 5.2 | Patient & Family Education Strategy | |

| 5.3 | Program Evaluation Strategy | |

| 5.4 | Model for Multidisciplinary Tumour Review Board | |

| 5.5 | Program Sustainability & Expansion Plan | |

| 4:30 p.m. | 6.0 | Breakout Session Report Back & Large Group Discussion |

| 5:00 p.m. | 7.0 | Closing Remarks & Next Steps |

Appendix E. Program Implementation Prioritization—Individual Results

| Health Care Provider Education | Patient and Family Education | Patient Care Implementation | Program Expansion and Sustainability | Research Priorities | MDC Tumor Board Review | Evaluation Strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent | Rank in order of prioritization 1–7 | ||||||

| 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 3 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 7 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | - | 6 |

| 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | 4 | - |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 6 |

| 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 |

| 11 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 12 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 2 |

| 13 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 7 |

| 14 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 15 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 |

| 16 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| 17 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 |

| 18 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 |

References

- Canadian Parternship Against Cancer Framework for the Care and Support for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/framework-adolescents-young-adults/ (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Coccia, P.F.; Pappo, A.S.; Beaupin, L.; Borges, V.F.; Borinstein, S.C.; Chugh, R.; Dinner, S.; Folbrecht, J.; Frazier, A.L.; Goldsby, R.; et al. Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018, 16, 66–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Cancer Institute Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Canadian Parternship Against Cancer Adolescents & Young Adults with Cancer: A System Performance Report Toronto, ON, Canada. 2017. Available online: https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Adolescents-and-young-adults-with-cancer-EN.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Canadian Parternship Against Cancer Person-Centred Perspective Indicators in Canada: A Reference Report. Adults and Young Adults with Cancer. Toronto, ON, Canada. 2017. Available online: https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Adolescents-and-Young-Adults-with-Cancer-Reference-Report-EN.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Barr, R.; Rogers, P.; Schacter, B. Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Towards Better Outcomes in Canada. Preamble. Cancer 2011, 117, 2239–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youth Cancer Service: Canteen Australian Youth Cancer Framework for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Available online: https://www.canteen.org.au/health-education/measures-manuals/australian-youth-cancer-framework (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- NHS England NHS Commissioning Children and Young People’s Cancer. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/group-b/b05/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Bleyer, A.; Barr, R. Cancer in Young Adults 20 to 39 Years of Age: Overview. Semin. Oncol. 2009, 36, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leading Causes of Death in Canada-2009 Ten Leading Causes of Death by Selected Age Groups, by Sex, Canada 1-15 to 24 Years. 2009. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/84-215-x/84-215-x2012001-eng.htm (accessed on 25 February 2009).

- Lewis, D.R.; Siembida, E.J.; Seibel, N.L.; Smith, A.W.; Mariotto, A.B. Survival Outcomes for Cancer Types with the Highest Death Rates for Adolescents and Young Adults, 1975-2016. Cancer 2021, 127, 4277–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisogno, G.; Compostella, A.; Ferrari, A.; Pastore, G.; Cecchetto, G.; Garaventa, A.; Indolfi, P.; De Sio, L.; Carli, M. Rhabdomyosarcoma in Adolescents: A Report from the AIEOP Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. Cancer 2012, 118, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatia, S.; Landier, W.; Shangguan, M.; Hageman, L.; Schaible, A.N.; Carter, A.R.; Hanby, C.L.; Leisenring, W.; Yasui, Y.; Kornegay, N.M.; et al. Nonadherence to Oral Mercaptopurine and Risk of Relapse in Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2094–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasme, J.F.; Morfouace, M.; Grill, J.; Martinot, A.; Amalberti, R.; Bons-Letouzey, C.; Chalumeau, M. Delays in Diagnosis of Paediatric Cancers: A Systematic Review and Comparison with Expert Testimony in Lawsuits. Lancet Oncol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canner, J.; Alonzo, T.A.; Franklin, J.; Freyer, D.R.; Gamis, A.; Gerbing, R.B.; Lange, B.J.; Meshinchi, S.; Woods, W.G.; Perentesis, J.; et al. Differences in Outcomes of Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia for Adolescent/Young Adult and Younger Patients: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2013, 119, 4162–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Identifying and Addressing the Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Workshop Summary. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24479202/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Ferrari, A.; Stark, D.; Peccatori, F.A.; Fern, L.; Laurence, V.; Gaspar, N.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Smith, O.; De Munter, J.; Derwich, K.; et al. Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) with Cancer: A Position Paper from the AYA Working Group of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE). ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albritton, K.H.; Wiggins, C.H.; Nelson, H.E.; Weeks, J.C. Site of Oncologic Specialty Care for Older Adolescents in Utah. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4616–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, C. The Delphi Technique: Myths and Realities. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 41, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsu, C.; Sandford, B. The Delphi Technique: Making Sense of Consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.W.; Parsons, H.M.; Kent, E.E.; Bellizzi, K.; Zebrack, B.J.; Keel, G.; Lynch, C.F.; Rubenstein, M.B.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Cress, R.; et al. Unmet Support Service Needs and Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: The AYA HOPE Study. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barr, R.D.; Ferrari, A.; Ries, L.; Whelan, J.; Bleyer, W.A. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebrack, B.J.; Corbett, V.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Meeske, K.A.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Block, R.; Zeman, D.T.; Cole, S. Psychological Distress and Unsatisfied Need for Psychosocial Support in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients during the First Year Following Diagnosis. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayes-Lattin, B.; Mathews-Bradshaw, B.; Siegel, S. Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Training for Health Professionals: A Position Statement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4858–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Princess Margaret Cancer Centre AYA Program, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. Available online: https://www.uhn.ca/PrincessMargaret/Clinics/Adolescent_Young_Adult_Oncology (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Alberta Health Services; CancerControl Alberta Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Patient Navigation. Available online: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/cca/if-cca-adolescent-young-adult-patient-navigation.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

| Domain | Score | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Patient care implementation | 4.67 | Establish referral pathways for pre-defined high problem issues (such as suicide, psychosocial distress, fertility preservation, urgent end of life symptom management) |

| Patient care implementation | 4.66 | Develop referral pathways for patients referred to BC Cancer, BCCH, VGH based on age and diagnosis |

| Patient care implementation | 4.64 | Create process so all AYA patients offered AYA program consultation with advanced practice nurse (APN) and counselor |

| Program mission and goals | 4.61 | Program mission: create a provincial interdisciplinary cancer program for AYA aged 15–29 years that will regionally implement recommendations across all BC Cancer sites in partnership with BCCH |

| Patient care implementation | 4.57 | Create process so all AYA patients offered follow-up with APN or counselor during treatment trajectory |

| Program expansion and sustainability | 4.56 | Foster relationships with motivated survivors, patients, and families for ongoing advocacy |

| Patient care implementation | 4.53 | Ensure all AYA patients screened for distress at intake |

| HCP education | 4.53 | HCP needs assessment survey topic: the unique psychosocial needs of AYA |

| Patient and family education | 4.5 | Develop patient education materials on survivorship and late effects for AYA |

| Patient and family education | 4.48 | Develop patient education materials on fertility preservation and counseling |

| Score | Program Item | Component |

|---|---|---|

| 4.67 | Establish pathways for high problem issues (such as suicide, psychosocial distress, fertility preservation, urgent end of life symptom management) | Patient Care |

| 4.66 | Create referral pathways at each institution based on age and diagnosis | Patient Care |

| 4.64 | Ensure all AYA patients offered AYA program consultation with advanced practice nurse (APN) and counselor | Patient Care |

| 4.57 | Create process so all AYA patients offered follow-up with APN or counselor during treatment trajectory | Patient Care |

| 4.56 | Foster relationships with motivated survivors, patients, and families for ongoing advocacy | Sustainability |

| 4.53 | HCP education topic: the unique psychosocial needs of AYA | HCP Education |

| 4.50 | Patient education materials on survivorship and late effects for AYA | Patient/Family Education |

| Domain Priority | Description of Priority Item | Provincial Task | Regional Task |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient care implementation | Establish referral pathways for pre-defined high problem issues (such as suicide, psychosocial distress, fertility preservation, urgent end of life symptom management) | Establish provincial working group to create best practice standard operating procedures, including appropriate screening tools and timelines for access to care | Identify available local resources |

| Establish locations for alternate care when local resources lacking | |||

| Develop referral pathways for patients referred to different locations based on age and diagnosis | Clarify and establish local limitations through process mapping | ||

| Establish human resource targets for optimal staffing | |||

| Create process so all AYA patients offered AYA program consultation with advanced practice nurse (APN) and counselor | Develop human resource job descriptions for AYA program staff and establish number of staff needed per population | Determine if referral will happen at new patient registration or after first consultation | |

| Create process so all AYA patients offered follow-up with APN or counselor during treatment trajectory | Create standards for timelines to referral, and frequency of follow-up assessments based on disease site | Automate and deliver routine screening for AYA-specific distress factors | |

| Ensure all AYA patients screened for distress at intake | |||

| Health care provider education | HCP needs assessment survey topic: the unique psychosocial needs of AYA | Establish funding and education opportunities for various AYA HCPs | Create local standards for continuing education opportunities |

| Patient and family education | Develop patient education materials on survivorship and late effects for AYA | Create electronic and written resources | Tailor individual education to patient needs by front-line staff |

| Develop patient education materials on fertility preservation and counseling | Provide easily identifiable mechanism for navigating to resource (i.e., provincial website) | Local referrals to appropriate regional centers | |

| Program expansion and sustainability | Foster relationships with motivated survivors, patients, and families for ongoing advocacy | Support and maintain patient and family advisory mechanisms | Promote engagement among motivated AYA patients and family |

| Identify and recruit ongoing participants specific to AYA cancer | Direct individuals to available opportunities |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Surujballi, J.; Chan, G.; Strahlendorf, C.; Srikanthan, A. Setting Priorities for a Provincial Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4034-4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060322

Surujballi J, Chan G, Strahlendorf C, Srikanthan A. Setting Priorities for a Provincial Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program. Current Oncology. 2022; 29(6):4034-4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060322

Chicago/Turabian StyleSurujballi, Julian, Grace Chan, Caron Strahlendorf, and Amirrtha Srikanthan. 2022. "Setting Priorities for a Provincial Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program" Current Oncology 29, no. 6: 4034-4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060322

APA StyleSurujballi, J., Chan, G., Strahlendorf, C., & Srikanthan, A. (2022). Setting Priorities for a Provincial Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Program. Current Oncology, 29(6), 4034-4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29060322