Canadian Guideline on the Management of a Positive Human Papillomavirus Test and Guidance for Specific Populations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

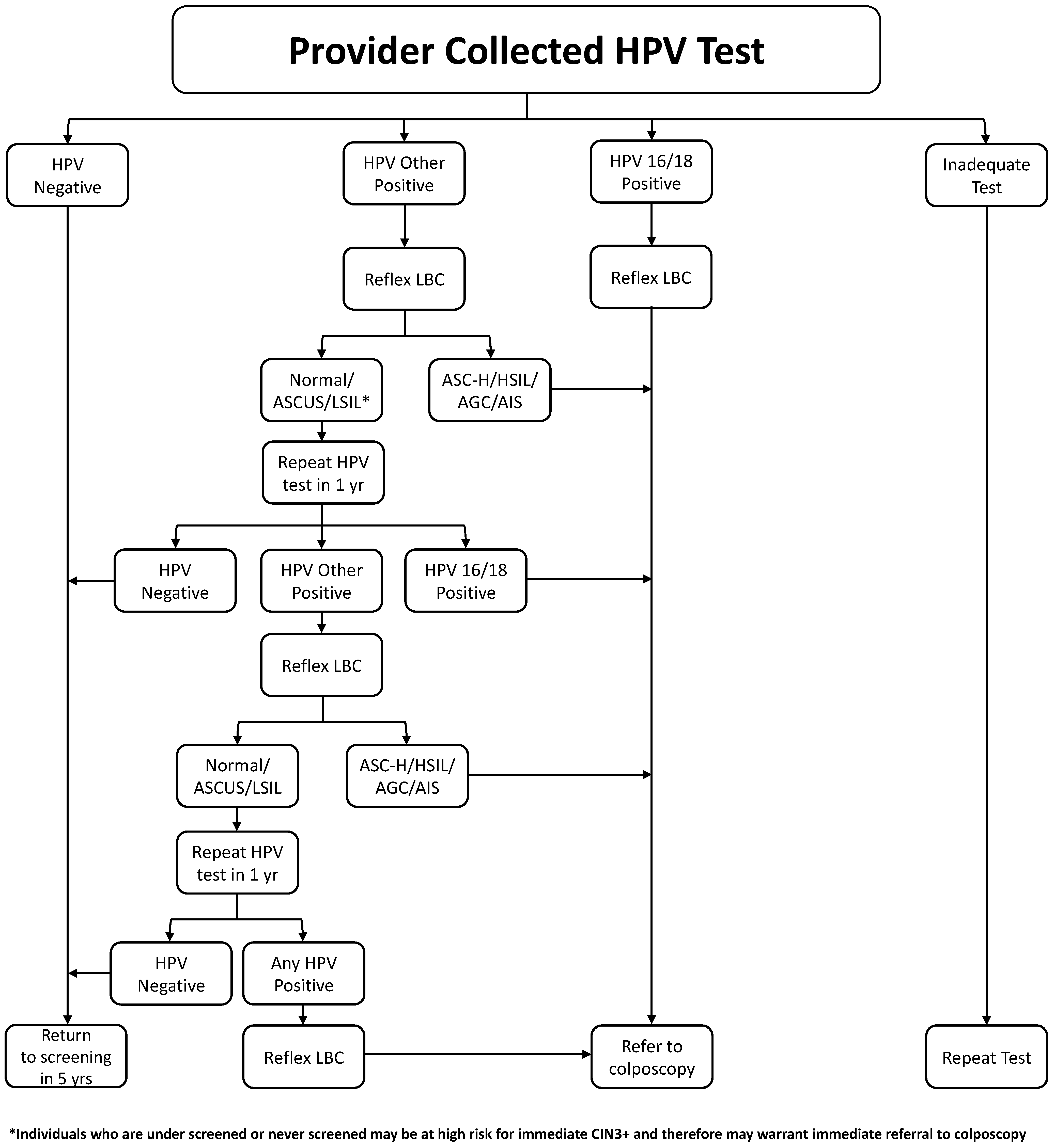

3.1. HPV Positive Test Management

- Recommendations:

- HPV tests providing partial genotyping information are preferred. (strong, high)

- Reflex liquid-based cytology should be performed on all HPV-positive samples. (strong, high)

- Persons testing positive for HPV 16 or 18 should be referred for colposcopy, regardless of reflex testing result. (strong, high)

- Persons testing positive for other HR types should be referred to colposcopy if their cytology shows AGC, ASC-H, HSIL, or cancer. (strong, high)

- Persons testing positive for other high types with normal, ASCUS, or LSIL cytology should not be referred to colposcopy but retested (HPV and reflex cytology) at 12 and 24 months. If, at 24 months, there is persistent HR–HPV positivity, regardless of cytology, they should be referred to colposcopy. (strong, high)

- There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of p16 and DNA methylation as triage tools following a positive HPV test. (conditional, low)

3.1.1. Triage by Cytology

3.1.2. Triage by HPV Genotype

3.1.3. Triage by Genotyping and Cytology

3.1.4. Triage by p16 Testing, E6/E7 mRNA and DNA Methylation

3.2. Self-Sampling for under Screened Populations

- Recommendations:

- Self-sampling may be mailed to identify non-attenders to cervical screening programs, as this has been shown in many studies to increase the uptake of screening. (strong, moderate)

- Self-sampling, coupled with face-to-face interactions, was even more effective with community health workers, nurses, or health outreach workers conducting home visits. (strong, moderate)

3.3. Self-Sampling for the General Population

- Recommendations:

- Self-sampling could be offered to Canadian individuals with a cervix. (weak, moderate)

- Individuals should be informed that in case of a positive HPV test, they would require an appointment with a health care provider to undergo a pelvic speculum exam to obtain a Pap test or may be referred for colposcopy assessment if HR-HPV 16/18 positive. (weak, moderate)

3.4. Management of a Positive HPV Test in Immunocompromised Populations

- Recommendations:

- Individuals with immunocompromised status and a positive HR–HPV test should go directly to a colposcopy, regardless of HR–HPV genotype and cytology. (conditional, low)

- Management, once in colposcopy, should follow the same guidelines as the immunocompetent population. (conditional, moderate).

3.5. Management of a Positive HPV Test in the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Two Spirit Populations (LGBTQ2S+)

- Recommendations:

- It is recommended that primary-care providers include a process of asking patients for their identifiers, including gender at birth and their current gender to aid in the identification of patients in need of ongoing cervical screening (e.g., individuals who identify as male who have cervix). (conditional, moderate)

- HPV self-collected samples should be offered to patients who, despite a respectful and patient-centered environment, are unable to undergo provider-collected cervical samples, or simply prefer self-sampling. (conditional, moderate)

- All individuals with a cervix who have ever been sexually active should undergo routine cervical screening regardless of their gender or the gender of their sexual partners. (Strong, high)

- Referring providers and colposcopists must be respectful of gender identity and create an environment that is safe and for all individuals with a cervix regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation. (strong, moderate)

3.6. Special Consideration and Management of a Positive HPV Test in First Nations, Inuit and Métis

- Recommendations:

- It is recommended that primary-care providers and colposcopists increase their understanding and knowledge of their local First Nations, Inuit, and/or Métis communities to work towards building relationships, knowledge translation, and understanding. (strong, moderate)

- It is recommended that colposcopy providers increase cultural safety and trauma awareness training to all persons working in the facility. (strong, moderate)

- It is recommended that colposcopists champion alternate approaches, including, but not limited to, the creation of a space and workflow that avoid re-traumatization as well as recognize local Indigenous cultures and land, addresses fears of abuse and coercion honestly, supports the patient both in the appointment and at home, and offers Cultural Support and advocacy as needed. (strong, moderate)

- -

- Practice humility; know your own beliefs and honour the beliefs and practices of your clients. Treat others how you would like to be treated.

- -

- Reflect on your own assumptions and positions of power within the health care system.

- -

- Do not offer opinion, but only the best medical evidence. Ensure informed choice is maintained free of bias and coercion. Consult and share unbiased evidence-based resources, i.e., 1800 Sex Sense, Options for Sexual Health, SOGC.

- -

- Listen to what the client wants, fears, and is worrying about.

- -

- Recognize that First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities have strategies of caring for individuals from preconception to elderhood that have been passed down orally through the generations.

- -

- Seek to draw from oral tradition by using stories to demonstrate cultural practices, beliefs, and values as evidence of healthy and protective ways of being. (Ref: Smylie).

- -

- Learn and incorporate culture, ceremony, and traditions into care. Ensuring this education and work is done in collaboration with the community you serve.

- -

- Work to facilitate timely access to appropriate supports for mental health and wellness, including cultural and/or traditional supports at home when possible and consider virtual care when not possible.

- -

- Facilitate support services.

- -

- Talk about ways to support cultural connections.

- -

- Maintain awareness and compassion regarding possible trauma/intergenerational trauma.

- -

- Be flexible to the needs of the community.

- -

- Ensure guidelines are culturally safe, applicable to rural and remote locations, clearly communicated, and include flow charts of actions.

- -

- Start conversations with families early to ensure there are contingency plans in place to provide a continuum of care/support for mothers and infants particularly if travelling for care.

- -

- Be aware of the complexities of leaving/returning to communities.

- Do not have the patient undress before seeing them.

- Build trust by calling the patient by name or meeting them in advance of appointment, allowing time to answer questions, and explain specific details of the procedure. Ideally, the person calling the patient is the person performing the examination and/or is going to be in the room during the examination (i.e., nursing).

- Consider utilization of an Indigenous liaison to be involved in communication and care.

- Allow a support person to attend the appointment.

- Acknowledge and respect concerns the patient may have regarding coerced sterilization and having an honest conversation about fertility risks.

- Provide clear next steps following the assessment/procedure ensuring community resources, and ensure supports are in place at home and known to the patient.

- Create a culturally safe and welcoming environment by using artwork by local First Nations artists to represent the community throughout the office.

- Post land acknowledgements in the office/clinic.

- Ensure all members of the team are introduced and roles defined, and the purpose of each room/piece of equipment is explained.

3.7. Management of a Positive HPV Test in Remote Areas, Immigrants and Newcomers to Canada

- Recommendations:

- For individuals living in rural and remote areas of Canada, HPV self-sampling techniques facilitated by mail programs or obtained from local health facilities should be strongly considered to overcome geographical barriers to cervix screening. Care pathways to obtain pap specimens and colposcopy should be in place. (conditional, moderate)

- HPV self-sampling should be considered among immigrants and newcomers to Canadian populations as an acceptable alternative to provider-collected cervical screening where cultural barriers may inhibit provider-based screening uptake. (conditional, moderate)

3.8. Management of a Positive HPV Test Following Hysterectomy

- Recommendation:

- HPV vault testing is not recommended for individuals who have undergone hysterectomy for benign diseases with no prior history of abnormal pap smears. (strong, moderate)

- Patients with LSIL on hysterectomy specimen should have an HPV test at 6–12 months; if negative, they require no further follow-up. (conditional, moderate)

- Patients with a previous history of treated HSIL (CIN2/3) who had a negative HPV test thereafter and have a subsequent hysterectomy for benign indications and have no cervical pathology do not need any follow-up. (strong, moderate)

- Patients with a previous history of treated HSIL (CIN2/3) who have had no HPV-based test following treatment, have a subsequent hysterectomy for benign indications, and have no cervical pathology should have an HPV test at 12 months; if negative, they require no further follow-up. (conditional, low)

- Patients who have a hysterectomy for HSIL (CIN2/3) and have residual cervical pathology (LSIL/HSIL) should have an HPV test at 12 months; if negative, they require no further follow-up. (conditional, low)

- Patients who undergo a hysterectomy for AIS should have three consecutive annual HPV tests, followed by HPV testing every 3 years. (strong, low)

- Patients who have a history of AIS and have been discharged from colposcopy and undergo a hysterectomy for another reason should have HPV testing every 3 years. (conditional, low)

- Patients who undergo HPV testing post-hysterectomy should have reflex cytology if positive HR–HPV is detected. Referrals to colposcopy should be made for results with HR–HPV 16/18 and any cytology showing HSIL/ASC-H. (strong, moderate)

- Patients with cervical carcinoma on hysterectomy specimens are not covered by this guideline and should be followed according to gynecologic oncologist recommendation. (conditional, moderate)

3.9. Screening and Management of a Positive HPV Test according to Vaccination Status

- Recommendation:

- Screening and colposcopy algorithms should be the same, irrespective of HPV vaccination status. (conditional, low)

3.10. Wait Times for Referral to Colposcopy

- Recommendations:

- Individuals with HR HPV16/18 with any cytology results should be seen within 6 weeks of referral (conditional, low)

- Individuals with an HR–HPV “other” positive test and HSIL/ASC-H/AGC should be seen in colposcopy within 6 weeks of referral. (conditional, low).

- Individuals with an HR–HPV “other” positive test meeting criteria for referral should be seen in colposcopy within 12 weeks of referral. (conditional, low).

- Individuals with an HR–HPV positive test and cytology that is suggested of carcinoma should be seen in colposcopy as soon as possible, ideally within 2 weeks of referral. (conditional, low).

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, D.; Poirier, A.; Smith, L.; Aziz, L.S.; Ellison, L.; Fitzgerald, N.; Saint-Jacques, N.; Turner, D.; Weir, H.K.; Woods, R.; et al. Members of the Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee Analytic Leads Additional Analysis Project Management.

- CPAC. Action Plan for the Elimation of Cervical Cancer in Canada; CPAC, Canada. 2020. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/elimination-cervical-cancer-action-plan/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Bulkmans, N.W.; Berkhof, J.; Rozendaal, L.; van Kemenade, F.J.; Boeke, A.J.; Bulk, S.; Voorhorst, F.J.; Verheijen, R.H.; van Groningen, K.; Boon, M.E.; et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1764–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijkaart, D.C.; Berkhof, J.; Rozendaal, L.; van Kemenade, F.J.; Bulkmans, N.W.; Heideman, D.A.; Kenter, G.G.; Cuzick, J.; Snijders, P.J.; Meijer, C.J. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: Final results of the POBASCAM. randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naucler, P.; Ryd, W.; Törnberg, S.; Strand, A.; Wadell, G.; Elfgren, K.; Rådberg, T.; Strander, B.; Johansson, B.; Forslund, O.; et al. Human Papillomavirus and Papanicolaou Tests to Screen for Cervical Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, G.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; Carozzi, F.; Confortini, M.; Dalla Palma, P.; Del Mistro, A.; Ghiringhello, B.; Girlando, S.; Gillio-Tos, A.; De Marco, L.; et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, G.; Dillner, J.; Elfström, K.M.; Tunesi, S.; Snijders, P.J.; Arbyn, M.; Kitchener, H.; Segnan, N.; Gilham, C.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014, 383, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvard, V.; Wentzensen, N.; Mackie, A.; Berkhof, J.; Brotherton, J.; Giorgi-Rossi, P.; Kupets, R.; Smith, R.; Arrossi, S.; Bendahhou, K.; et al. The IARC Perspective on Cervical Cancer Screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Serrano, B.; Roura, E.; Alemany, L.; Cowan, M.; Herrero, R.; Poljak, M.; Murillo, R.; Broutet, N.; Riley, L.M.; et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and age-specific coverage estimates for 202 countries and territories worldwide: A review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1115–e1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CADTH Database Search Filters. Available online: https://www.cadth.ca/strings-attached-cadths-database-search-filters (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Lee, J.G.L.; Ylioja, T.; Lackey, M. Identifying Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Search Terminology: A Systematic Review of Health Systematic Reviews. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayrand, M.-H.; Duarte-Franco, E.; Rodrigues, I.; Walter, S.D.; Hanley, J.; Ferenczy, A.; Ratnam, S.; Coutlée, F.; Franco, E.L. Human Papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou Screening Tests for Cervical Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ascus-Lsil Traige Study Group. A randomized trial on the management of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology interpretations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, G.S.; van Niekerk, D.; Krajden, M.; Smith, L.W.; Cook, D.; Gondara, L.; Ceballos, K.; Quinlan, D.; Lee, M.; Martin, R.E.; et al. Effect of Screening With Primary Cervical HPV Testing vs Cytology Testing on High-grade Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia at 48 Months: The HPV FOCAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gilham, C.; Sargent, A.; Kitchener, H.C.; Peto, J. HPV testing compared with routine cytology in cervical screening: Long-term follow-up of ARTISTIC RCT. Health Technol. Assess. 2019, 23, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chan, K.K.L.; Liu, S.S.; Wei, N.; Ngu, S.F.; Chu, M.M.Y.; Tse, K.Y.; Lau, L.S.K.; Cheung, A.N.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.S. Primary HPV testing with cytology versus cytology alone in cervical screening-A prospective randomized controlled trial with two rounds of screening in a Chinese population. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzensen, N.; Schiffman, M.; Palmer, T.; Arbyn, M. Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 76 (Suppl. 1), S49–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saraiya, M.; Cheung, L.C.; Soman, A.; Mix, J.; Kenney, K.; Chen, X.; Perkins, R.B.; Schiffman, M.; Wentzensen, N.; Miller, J. Risk of cervical precancer and cancer among uninsured and underserved women from 2009 to 2017. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, e361–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.A.; Sherrah, M.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P.E.; Arbyn, M.; Gertig, D.; Caruana, M.; Wrede, C.D.; Saville, M.; Canfell, K. National experience in the first two years of primary human papillomavirus (HPV) cervical screening in an HPV vaccinated population in Australia: Observational study. BMJ 2022, 376, e068582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, M.; Doorbar, J.; Wentzensen, N.; de Sanjosé, S.; Fakhry, C.; Monk, B.J.; Stanley, M.A.; Franceschi, S. Carcinogenic human papillomavirus infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M. Pathology and epidemiology of HPV infection in females. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 117, S5–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Bruni, L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Saraiya, M.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e191–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moscicki, A.B.; Shiboski, S.; Broering, J.; Powell, K.; Clayton, L.; Jay, N.; Darragh, T.M.; Brescia, R.; Kanowitz, S.; Miller, S.B.; et al. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection as measured by repeated DNA testing in adolescent and young women. J. Pediatr. 1998, 132, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscicki, A.B. Management of adolescents who have abnormal cytology and histology. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 35, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Woodman, C.B.J.; Collins, S.; Winter, H.; Bailey, A.; Ellis, J.; Prior, P.; Yates, M.; Rollason, T.P.; Young, L.S. Natural history of cervical human papillomavirus infection in young women: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2001, 357, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjaer, S.K.; van den Brule, A.J.; Paull, G.; Svare, E.I.; Sherman, M.E.; Thomsen, B.L.; Suntum, M.; Bock, J.E.; Poll, P.A.; Meijer, C.J. Type specific persistence of high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) as indicator of high grade cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in young women: Population based prospective follow up study. BMJ 2002, 325, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kjær, S.K.; Frederiksen, K.; Munk, C.; Iftner, T. Long-term absolute risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse following human papillomavirus infection: Role of persistence. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schiffman, M.; Wentzensen, N.; Wacholder, S.; Kinney, W.; Gage, J.C.; Castle, P.E. Human papillomavirus testing in the prevention of cervical cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCredie, M.R.; Sharples, K.J.; Paul, C.; Baranyai, J.; Medley, G.; Jones, R.W.; Skegg, D.C. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, M.; Egemen, D.; Raine-Bennett, T.R.; Cheung, L.C.; Befano, B.; Poitras, N.E.; Lorey, T.S.; Chen, X.; Gage, J.C.; Castle, P.E.; et al. A Study of Partial Human Papillomavirus Genotyping in Support of the 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, M.; Boyle, S.; Raine-Bennett, T.; Katki, H.A.; Gage, J.C.; Wentzensen, N.; Kornegay, J.R.; Apple, R.; Aldrich, C.; Erlich, H.A.; et al. The Role of Human Papillomavirus Genotyping in Cervical Cancer Screening: A Large-Scale Evaluation of the cobas HPV Test. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2015, 24, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, T.C.; Stoler, M.H.; Behrens, C.M.; Apple, R.; Derion, T.; Wright, T.L. The ATHENA human papillomavirus study: Design, methods, and baseline results. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, e41–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egemen, D.; Cheung, L.C.; Chen, X.; Demarco, M.; Perkins, R.B.; Kinney, W.; Poitras, N.; Befano, B.; Locke, A.; Guido, R.S.; et al. Risk Estimates Supporting the 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.B.; Guido, R.S.; Castle, P.E.; Chelmow, D.; Einstein, M.H.; Garcia, F.; Huh, W.K.; Kim, J.J.; Moscicki, A.-B.; Nayar, R.; et al. 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 102–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Dong, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, K.; Pan, M.; Deng, Z.; Wang, P.; Du, Y.; Lu, W. Performance of human papillomavirus (HPV) mRNA testing and HPV 16 and 18/45 genotyping combined with age stratification in the triaging of women with ASC-US cytology. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 164, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Carozzi, F.; Ronco, G.; Allia, E.; Bisanzi, S.; Gillio-Tos, A.; De Marco, L.; Rizzolo, R.; Gustinucci, D.; Del Mistro, A.; et al. p16/ki67 and E6/E7 mRNA Accuracy and Prognostic Value in Triaging HPV DNA-Positive Women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, W.W.; Steenbergen, R.D.M.; Heideman, D.A.M.; Kenter, G.G.; Meijer, C.J.L.M. The use of host cell DNA methylation analysis in the detection and management of women with advanced cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A review. BJOG 2021, 128, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, H.; Yeh, P.T.; Oguntade, H.; Kennedy, C.E.; Narasimhan, M. HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening: A systematic review of values and preferences. BMJ. Glob. Health 2021, 6, e003743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.J.; Maynard, B.R.; Loux, T.; Fatla, J.; Gordon, R.; Arnold, L.D. The acceptability of self-sampled screening for HPV DNA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2017, 93, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarinci, I.C.; Li, Y.; Tucker, L.; Campos, N.G.; Kim, J.J.; Peral, S.; Castle, P.E. Given a choice between self-sampling at home for HPV testing and standard of care screening at the clinic, what do African American women choose? Findings from a group randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2021, 142, 106358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, T.; Marjoram, J.; Burgess, S.; Montgomery, L.; Vail, A.; Callan, N.; Jacob, S.; Hawkes, D.; Saville, M.; Bailey, J. Uptake and acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling in rural and remote aboriginal communities: Evaluation of a nurse-led community engagement model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.H.; Huang, H.J.; Cheng, H.H.; Chang, C.J.; Yang, L.Y.; Huang, C.C.; Chang, W.Y.; Hsueh, S.; Chao, A.; Wang, C.J.; et al. Self-sampling HPV test in women not undergoing Pap smear for more than 5 years and factors associated with under-screening in Taiwan. J. Med. Assoc. 2016, 115, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersson, S.; Belkic, K.; Mints, M.; Ostensson, E. Acceptance of Self-Sampling Among Long-Term Cervical Screening Non-Attenders with HPV-Positive Results: Promising Opportunity for Specific Cancer Education. J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Educ. 2021, 36, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reiter, P.L.; Shoben, A.B.; McDonough, D.; Ruffin, M.T.; Steinau, M.; Unger, E.R.; Paskett, E.D.; Katz, M.L. Results of a Pilot Study of a Mail-Based Human Papillomavirus Self-Testing ProgrAm. for Underscreened Women From Appalachian Ohio. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2019, 46, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Des Marais, A.C.; Zhao, Y.; Hobbs, M.M.; Sivaraman, V.; Barclay, L.; Brewer, N.T.; Smith, J.S. Home Self-Collection by Mail to Test for Human Papillomavirus and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maza, M.; Melendez, M.; Masch, R.; Alfaro, K.; Chacon, A.; Gonzalez, E.; Soler, M.; Conzuelo-Rodriguez, G.; Gage, J.C.; Alonzo, T.A.; et al. Acceptability of self-sampling and human papillomavirus testing among non-attenders of cervical cancer screening programs in El Salvador. Prev. Med. 2018, 114, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racey, C.S.; Gesink, D.C.; Burchell, A.N.; Trivers, S.; Wong, T.; Rebbapragada, A. Randomized Intervention of Self-Collected Sampling for Human Papillomavirus Testing in Under-Screened Rural Women: Uptake of Screening and Acceptability. J. Womens Health 2016, 25, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F.; Mullins, R.; English, D.R.; Simpson, J.A.; Drennan, K.T.; Heley, S.; Wrede, C.D.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Saville, M.; Gertig, D.M. Women’s experience with home-based self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datta, G.D.; Mayrand, M.H.; Qureshi, S.; Ferre, N.; Gauvin, L. HPV sampling options for cervical cancer screening: Preferences of urban-dwelling Canadians in a changing paradigm. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, e171–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.T.; Kennedy, C.E.; de Vuyst, H.; Narasimhan, M. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlgren, H.; Sparén, P.; Elfgren, K.; Miri, A.; Elfström, K. Feasibility of sending a direct send HPV self-sampling kit to long-term non-attenders in an organized cervical screening program. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 268, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, A. Prevention, Incidence, and Survival of Cervical Cancer in Sweden; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, E.J.; Geller, S.; Sibanda, N.; Stevenson, K.; Denmead, L.; Adcock, A.; Cram, F.; Hibma, M.; Sykes, P.; Lawton, B. Reaching under-screened/never-screened indigenous peoples with human papilloma virus self-testing: A community-based cluster randomised controlled trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 61, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstson, A.; Forslund, O.; Borgfeldt, C. Promotion of Cervical Screening among Long-term Non-attendees by Human Papillomavirus Self-sampling. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 26, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, F.; O’Conaill, C.; Templeton, K.; Lotocki, R.; Fischer, G.; Manning, L.; Cormier, K.; Decker, K. Assessing the impact of mailing self-sampling kits for human papillomavirus testing to unscreened non-responder women in Manitoba. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 26, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Winer, R.L.; Lin, J.; Tiro, J.A.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Beatty, T.; Gao, H.; Kimbel, K.; Thayer, C.; Buist, D.S.M. Effect of Mailed Human Papillomavirus Test Kits vs Usual Care Reminders on Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake, Precancer Detection, and Treatment: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1914729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Mistro, A.; Frayle, H.; Ferro, A.; Fantin, G.; Altobelli, E.; Giorgi Rossi, P. Efficacy of self-sampling in promoting participation to cervical cancer screening also in subsequent round. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenan, R.T.; Troja, C.; Buist, D.S.M.; Tiro, J.A.; Lin, J.; Anderson, M.L.; Gao, H.; Green, B.B.; Winer, R.L. Economic Evaluation of Mailed Home-Based Human Papillomavirus Self-sampling Kits for Cervical Cancer Screening. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e234052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, P.; Godwin, M.; Ratnam, S.; Dawson, L.; Fontaine, D.; Lear, A.; Traverso-Yepez, M.; Graham, W.; Ravalia, M.; Mugford, G.; et al. Effect of vaginal self-sampling on cervical cancer screening rates: A community-based study in Newfoundland. BMC Womens Health 2015, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chao, Y.S.; McCormack, S. CADTH Rapid Response Reports. In HPV Self-Sampling for Primary Cervical Cancer Screening: A Review of Diagnostic Test Accuracy and Clinical Evidence—An Update, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Copyright © 2019; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M.H.J. Self-Sampling Devices for HPV Testing, Emerging Health Technologies. Available online: https://canjhealthtechnol.ca/index.php/cjht/article/view/eh0101/445 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Petignat, P.; Faltin, D.L.; Bruchim, I.; Tramèr, M.R.; Franco, E.L.; Coutlée, F. Are self-collected samples comparable to physician-collected cervical specimens for human papillomavirus DNA testing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Verdoodt, F.; Snijders, P.J.; Verhoef, V.M.; Suonio, E.; Dillner, L.; Minozzi, S.; Bellisario, C.; Banzi, R.; Zhao, F.H.; et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: A meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, N.J.; Ebisch, R.M.F.; Heideman, D.A.M.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Bekkers, R.L.M.; Molijn, A.C.; Meijer, C.J.L.M.; Quint, W.G.V.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Massuger, L.F.A.G.; et al. Performance of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia of grade 2 or worse: A randomised, paired screen-positive, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, N.J.; de Haan, Y.; Veldhuijzen, N.J.; Heideman, D.A.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Meijer, C.; Massuger, L.; van Kemenade, F.J.; Berkhof, J. Experience with HPV self-sampling and clinician-based sampling in women attending routine cervical screening in the Netherlands. Prev. Med. 2019, 125, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmeink, C.E.; Bekkers, R.L.; Massuger, L.F.; Melchers, W.J. The potential role of self-sampling for high-risk human papillomavirus detection in cervical cancer screening. Rev. Med. Virol. 2011, 21, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Medical Devices Active License Search. Available online: https://health-products.canada.ca/mdall-limh/prepareSearch-preparerRecherche.do (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Cadman, L.; Reuter, C.; Jitlal, M.; Kleeman, M.; Austin, J.; Hollingworth, T.; Parberry, A.L.; Ashdown-Barr, L.; Patel, D.; Nedjai, B.; et al. A Randomized Comparison of Different Vaginal Self-sampling Devices and Urine for Human Papillomavirus Testing-Predictors 5.1. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfell, K.; Smith, M.A.; Bateson, D.J. Self-collection for HPV screening: A game changer in the elimination of cervical cancer. Med. J. Aust 2021, 215, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creagh, N.S.; Zammit, C.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Saville, M.; McDermott, T.; Nightingale, C.; Kelaher, M. Self-collection cervical screening in the renewed National Cervical Screening Program: A qualitative study. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 215, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BC Cancer Agency. Cervix Self-Screening. Available online: www.screeningbc.ca/cervix-pilot (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Wielgos, A.A.; Pietrzak, B. Human papilloma virus-related premalignant and malignant lesions of the cervix and anogenital tract in immunocompromised women. Ginekol. Pol. 2020, 91, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.C.; Feldman, S.; Moscicki, A.-B. Risk of human papillomavirus infection in women with rheumatic disease: Cervical cancer screening and prevention. Rheumatology 2018, 57, v26–v33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cancer Council Australia. Screening in Immune-Deficient Women. Available online: https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cervical-cancer/cervical-cancer-screening/screening-in-immune-deficient-women (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- NHS England. Screening and Management of Immunosuppressed Individuals. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cervical-screening-programme-and-colposcopy-management/5-screening-and-management-of-immunosuppressed-individuals (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Moscicki, A.-B.; Flowers, L.; Huchko, M.J.; Long, M.E.; MacLaughlin, K.L.; Murphy, J.; Spiryda, L.B.; Gold, M.A. Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening in Immunosuppressed Women Without HIV Infection. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2019, 23, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Li, D.H.; Moskowitz, D.A. Comparing the Healthcare Utilization and Engagement in a Sample of Transgender and Cisgender Bisexual+ Persons. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berner, A.M.; Connolly, D.J.; Pinnell, I.; Wolton, A.; MacNaughton, A.; Challen, C.; Nambiar, K.; Bayliss, J.; Barrett, J.; Richards, C. Attitudes of transgender men and non-binary people to cervical screening: A cross-sectional mixed-methods study in the UK. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e614–e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatos, K.C. A Literature Review of Cervical Cancer Screening in Transgender Men. Nurs. Women Health 2018, 22, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bustamante, G.; Reiter, P.L.; McRee, A.-L. Cervical cancer screening among sexual minority women: Findings from a national survey. Cancer Causes Control CCC 2021, 32, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.-Y.; Choi-Kwon, S. Cervical Cancer Screening and Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among Korean Sexual Minority Women by Sex of Their Sexual Partners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, P.L.; McRee, A.L. Cervical cancer screening (Pap testing) behaviours and acceptability of human papillomavirus self-testing among lesbian and bisexual women aged 21-26 years in the USA. J. Fam. Plann Reprod Health Care 2015, 41, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saunders, C.L.; Massou, E.; Waller, J.; Meads, C.; Marlow, L.A.; Usher-Smith, J.A. Cervical screening attendance and cervical cancer risk among women who have sex with women. J. Med. Screen. 2021, 28, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branković, I.; Verdonk, P.; Klinge, I. Applying a gender lens on human papillomavirus infection: Cervical cancer screening, HPV DNA testing, and HPV vaccination. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branstetter, A.J.; McRee, A.L.; Reiter, P.L. Correlates of Human Papillomavirus Infection Among a National Sample of Sexual Minority Women. J. Womens Health 2017, 26, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solazzo, A.L.; Agenor, M.; Austin, S.B.; Chavarro, J.E.; Charlton, B.M. Sexual Orientation Differences in Cervical Cancer Prevention among a Cohort of U.S. Women Health Issues 2020, 30, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Kim, K. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Predictors Among U.S. Adults Aged 18 to 45 by Sexual Orientation. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 41, 1761–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRee, A.-L.; Gower, A.L.; Reiter, P.L. Preventive healthcare services use among transgender young adults. Int. J. Transgenderism 2018, 19, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, L.M.; Boscoe, F.P.; Feingold, B.J. Cancers Disproportionately Affecting the New York State Transgender Population, 1979–2016. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1260–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, N.; Oliffe, J.L.; Kelly, M.T.; Krist, J. Bridging Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening in Transgender Men: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Men Health 2020, 14, 1557988320925691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisly, N.L.; Imborek, K.L.; Miller, M.L.; Kaliszewski, S.D.; Williams, R.M.; Krasowski, M.D. Unique Primary Care Needs of Transgender and Gender Non-Binary People. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, D.; Hughes, X.; Berner, A. Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening among transgender men and non-binary people with a cervix: A systematic narrative review. Prev. Med. 2020, 135, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adkins, B.D.; Barlow, A.B.; Jack, A.; Schultenover, S.J.; Desouki, M.M.; Coogan, A.C.; Weiss, V.L. Characteristic findings of cervical Papanicolaou tests from transgender patients on androgen therapy: Challenges in detecting dysplasia. Cytopathol. Off. J. Br. Soc. Clin. Cytol. 2018, 29, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, R.M.; Kelting, S.; Madan, R.; O’Neil, M.; Dennis, K.; Fan, F. Cervical Papanicolaou tests in the female-to-male transgender population: Should the adequacy criteria be revised in this population? An Institutional Experience. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 2021, 10, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.P.A.; Kukkar, V.; Stemmer, M.N.; Khurana, K.K. Cytomorphologic findings of cervical Pap smears from female-to-male transgender patients on testosterone therapy. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020, 128, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Deutsch, M.B.; Peitzmeier, S.M.; White Hughto, J.M.; Cavanaugh, T.P.; Pardee, D.J.; McLean, S.A.; Panther, L.A.; Gelman, M.; Mimiaga, M.J.; et al. Test performance and acceptability of self- versus provider-collected swabs for high-risk HPV DNA testing in female-to-male trans masculine patients. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohr, S.; Gygax, L.N.; Imboden, S.; Mueller, M.D.; Kuhn, A. Screening for HPV and dysplasia in transgender patients: Do we need it? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 260, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, G.; Church, H.; Evans, C.; Jenkinson, N.; McClean, H.; Mohammed, H.; Munro, H.; Nambia, K.; Saunders, J.; Walton, L.; et al. 2019 UK National Guideline for consultations requiring sexual history taking: Clinical Effectiveness Group British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Int. J. STD AIDS 2020, 31, 920–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyers, S.; Garland, S.M.; Cruickshank, M.; Kyrgiou, M.; Arbyn, M. Cervical cancer prevention in transgender men: A review. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, A.F.; Drysdale, K.; Botfield, J.; Mooney-Somers, J.; Cook, T.; Newman, C.E. Navigating trans visibilities, trauma and trust in a new cervical screening clinic. Cult. Health Sex. 2022, 24, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahan, C.E.; Linn, K.; Guno, P.; Johnson, H.; Coldman, A.J.; Spinelli, J.J.; Caron, N.R. Cancer in First Nations people living in British Columbia, Canada: An analysis of incidence and survival from 1993 to 2010. Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-510-X2016001; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 18 July 2018; Tsinstikeptum 9, IRI [Census subdivision], British Columbia (table). Aboriginal Population Profile. 2016 Census.

- Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 98-510-X2016001; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 18 July 2018; Tsinstikeptum 10, IRI [Census subdivision], British Columbia (table). Aboriginal Population Profile. 2016 Census.

- Maar, M.; Burchell, A.; Little, J.; Ogilvie, G.; Severini, A.; Yang, J.M.; Zehbe, I. A Qualitative Study of Provider Perspectives of Structural Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening Among First Nations Women. Women Health Issues 2013, 23, e319–e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maar, M.; Wakewich, P.; Wood, B.; Severini, A.; Little, J.; Burchell, A.N.; Ogilvie, G.; Zehbe, I. Strategies for Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Amongst First Nations Communities in Northwest Ontario, Canada. Health Care Women Int. 2016, 37, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cerigo, H.; Macdonald, M.E.; Franco, E.L.; Brassard, P. Inuit women’s attitudes and experiences towards cervical cancer and prevention strategies in Nunavik, Quebec. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2012, 71, 17996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parliment of Canada The Senate Committee on Human Rights. Forced and Coerced Sterilization of Persons in Canada; Senate of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Datta, G.D.; Pana, M.P.; Mayrand, M.H.; Glenn, B. Racial/ethnic inequalities in cervical cancer screening in the United States: An outcome reclassification to better inform interventions and benchmarks. Prev. Med. 2022, 159, 107055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, M.; Lee, S.; Goopy, S.; Yang, H.; Rumana, N.; Abedin, T.; Turin, T.C. Barriers to cervical cancer screening faced by immigrant women in Canada: A systematic scoping review. BMC Womens Health 2018, 18, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrasquillo, O.; Seay, J.; Amofah, A.; Pierre, L.; Alonzo, Y.; McCann, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Trevil, D.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Kobetz, E. HPV Self-Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening Among Ethnic Minority Women in South Florida: A Randomized Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howard, M.; Lytwyn, A.; Lohfeld, L.; Redwood-Campbell, L.; Fowler, N.; Karwalajtys, T. Barriers to acceptance of self-sampling for human papillomavirus across ethnolinguistic groups of women. Can. J. Public Health 2009, 100, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobetz, E.; Seay, J.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Bispo, J.B.; Trevil, D.; Gonzalez, M.; Brickman, A.; Carrasquillo, O. A randomized trial of mailed HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women in South Florida. Cancer Causes Control 2018, 29, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofters, A.K.; Vahabi, M.; Fardad, M.; Raza, A. Exploring the acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling among Muslim immigrant women. Cancer Manag Res. 2017, 9, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tranberg, M.; Bech, B.H.; Blaakær, J.; Jensen, J.S.; Svanholm, H.; Andersen, B. HPV self-sampling in cervical cancer screening: The effect of different invitation strategies in various socioeconomic groups—A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vahabi, M.; Lofters, A. Muslim immigrant women’s views on cervical cancer screening and HPV self-sampling in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sewali, B.; Okuyemi, K.S.; Askhir, A.; Belinson, J.; Vogel, R.I.; Joseph, A.; Ghebre, R.G. Cervical cancer screening with clinic-based Pap test versus home HPV test among Somali immigrant women in Minnesota: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Cancer Med. 2015, 4, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Virtanen, A.; Nieminen, P.; Niironen, M.; Luostarinen, T.; Anttila, A. Self-sampling experiences among non-attendees to cervical screening. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 135, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montealegre, J.R.; Mullen, P.D.; Jibaja-Weiss, M.L.; Mendez, M.M.V.; Scheurer, M.E. Feasibility of Cervical Cancer Screening Utilizing Self-sample Human Papillomavirus Testing Among Mexican Immigrant Women in Harris County, Texas: A Pilot Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofters, A.; Devotta, K.; Prakash, V.; Vahabi, M. Understanding the Acceptability and Uptake of HPV Self-Sampling Amongst Women Under- or Never-Screened for Cervical Cancer in Toronto (Ontario, Canada): An Intervention Study Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, K.F.; Haefner, H.K.; Sarwar, S.F.; Nolan, T.E. Cytopathological findings on vaginal Papanicolaou smears after hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1559–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y. Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia in patients after total hysterectomy. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2021, 45, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, D.; Hultman, G.; DeKam, M.; Isaksson Vogel, R.; Downs, L.S., Jr.; Geller, M.A.; Le, C.; Melton, G.; Kulasingam, S. Excess Cost of Cervical Cancer Screening Beyond Recommended Screening Ages or After Hysterectomy in a Single Institution. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2018, 22, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schockaert, S.; Poppe, W.; Arbyn, M.; Verguts, T.; Verguts, J. Incidence of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia after hysterectomy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A retrospective study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, e111–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katki, H.A.; Schiffman, M.; Castle, P.E.; Fetterman, B.; Poitras, N.E.; Lorey, T.; Cheung, L.C.; Raine-Bennett, T.; Gage, J.C.; Kinney, W.K. Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women with HPV-positive and HPV-negative high-grade Pap results. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2013, 17, S50–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Public Health England. NHS Cervical Screening Programme Colposcopy and Programme Management; Programmes, N.S., Ed.; NHS: England, UK, 2016; updated 2023; Volume NHSCSP Publication Number 20. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.J.; Massad, L.S.; Kinney, W.; Gold, M.A.; Mayeaux, E.J., Jr.; Darragh, T.M.; Castle, P.E.; Chelmow, D.; Lawson, H.W.; Huh, W.K. A Common Clinical Dilemma: Management of Abnormal Vaginal Cytology and Human Papillomavirus Test Results. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2016, 20, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, S.J.; Krist, A.H.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kemper, A.R.; Kubik, M.; et al. Screening for Cervical Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 320, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Padilha, C.M.L.; Araújo, M.L.C.J.; Souza, S.A.L. Cytopathologic evaluation of patients submitted to radiotherapy for uterine cervix cancer. Rev. Assoc Med. Bras (1992) 2017, 63, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donken, R.; van Niekerk, D.; Hamm, J.; Spinelli, J.J.; Smith, L.; Sadarangani, M.; Albert, A.; Money, D.; Dobson, S.; Miller, D.; et al. Declining rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in British Columbia, Canada: An ecological analysis on the effects of the school-based human papillomavirus vaccination program. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcaro, M.; Castañon, A.; Ndlela, B.; Checchi, M.; Soldan, K.; Lopez-Bernal, J.; Elliss-Brookes, L.; Sasieni, P. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: A register-based observational study. Lancet 2021, 398, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillner, J.; Nygård, M.; Munk, C.; Hortlund, M.; Hansen, B.T.; Lagheden, C.; Liaw, K.-L.; Kjaer, S.K. Decline of HPV infections in Scandinavian cervical screening populations after introduction of HPV vaccination programs. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3820–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasieni, P.; Castanon, A. HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening—Authors’ reply. Lancet 2022, 399, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, D.R.; Corry, E.M.A.; Malagon, T.; O’Riain, C.; Franco, E.L.; Brennan, D.J. Modeling Cervical Cancer Screening Strategies With Varying Levels of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2115321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, R.; Windridge, P.; Gillman, M.S.; Sasieni, P.D. What cervical screening is appropriate for women who have been vaccinated against high risk HPV? A simulation study. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.J.; Burger, E.A.; Sy, S.; Campos, N.G. Optimal Cervical Cancer Screening in Women Vaccinated Against Human Papillomavirus. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pedersen, K.; Burger, E.A.; Nygård, M.; Kristiansen, I.S.; Kim, J.J. Adapting cervical cancer screening for women vaccinated against human papillomavirus infections: The value of stratifying guidelines. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 91, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, A.; Tapper, A.-M.; Leminen, A.; Sintonen, H.; Roine, R.P. Health-related quality of life and perception of anxiety in women with abnormal cervical cytology referred for colposcopy: An observational study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 169, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J. Colposcopic management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2012, 34, 1188–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayeaux, E.J., Jr.; Novetsky, A.P.; Chelmow, D.; Garcia, F.; Choma, K.; Liu, A.H.; Papasozomenos, T.; Einstein, M.H.; Massad, L.S.; Wentzensen, N.; et al. ASCCP Colposcopy Standards: Colposcopy Quality Improvement Recommendations for the United States. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2017, 21, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Policarpio, M.; Strub, S.; Jembere, N.; Kupets, R. Performance Indicators for Colposcopy in Ontario. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2020, 42, 144–149.e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HPV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytology | Pos HR HPV (Any) | Pos HPV 16 | Pos HPV 18 | Pos HPV Other |

| Normal | 3.4% [31] | 5.3% [31] | 3% [35] | 2% [35] |

| ASCUS | 4.4% [34] | 9–12.9% [31,36] | 5% [36] | 2.7–4.4% [34,36] |

| LSIL | 4.3% [34] | 11% [31] | 3% [35] | 4.3% [34] |

| ASC–H | 26% [34,35] | 28% [31,35] | 15% [31] | 26% [34,35] |

| HSIL | 49% [34,35] | 60% [31,35] | 30% [31,35] | 49% [34,35] |

|

| Study Country | Population | N | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersson et al., 2021 [44] Sweden | Women who had an HPV+ result on self-sampling and presented for diagnostic procedures | 515 (intervention) 479 (controls) | Self-sampling (kit sent by mail or opt-in online) |

|

| Reiter et al., 2019 [45] United States | Women aged 30 to 65 who have not been screened for at least 3 years | 51 (intervention) 52 (controls) | Self-sampling (kit sent by mail) |

|

| Des Marais et al., 2018 [46] United States | Low-income women aged 30 to 64 who have not been screened in at least 4 years | 284 | Two self-samplings (one at home and the other in the clinic) |

|

| Maza et al., 2018 [47] El Salvador | Women aged 30 to 59 who have not been screened in at least 3 years | 1869 | Self-sampling |

|

| Racey et al., 2016 [48] Canada (Ontario) | Women aged 30 to 70 who have not been screened for at least 30 months | 70 | Self-sampling (kit sent by mail) |

|

| Chou et al., 2016 [43] Taiwan | Women aged 35 to 80 who have not been screened in at least 5 years | 354 | Self-sampling |

|

| Sultana et al., 2015 [49] Australia (Victoria) | Women aged 30 to 69 years that either have never been screened or had not completed screening in the past 5 to 15 years | 1521 | Self-sampling |

|

| Datta et al., 2020 [50] Canada (Montreal) | Women aged 21 to 65 years that either have never been screened or had not completed screening in the past 3 years | 526 | Self-sampling |

|

|

| BC Association of Aboriginal Friendship Centres (n.d.). Doulas for Aboriginal Families Grant Program. https://bcaafc.com/dafgp/ Barney, Lucy (2020). Honouring Resilience: Providing Culturally Safe, Trauma-Informed Care for Indigenous Women and Families and COVID-19. Available upon request. First Nations Health Authority (2016). FNHA’s Policy Statement on Cultural Safety and Humility. http://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Policy-Statement-Cultural-Safety-and-Humility.pdf. First Nations Health Authority (n.d). FNHA’s Policy on Mental Health & Wellness. https://www.fnha.ca/WellnessSite/WellnessDocuments/FNHA-Policy-on-Mental-Health-and-Wellness.pdf. Hope for Wellness Helpline. (n.d.). https://www.hopeforwellness.ca/. Indigenous Corporate Training. (2020). Indigenous Peoples and COVID-19. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-peoples-and-covid-19. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation Report on Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action https://nctr.ca/records/reports/ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zigras, T.; Mayrand, M.-H.; Bouchard, C.; Salvador, S.; Eiriksson, L.; Almadin, C.; Kean, S.; Dean, E.; Malhotra, U.; Todd, N.; et al. Canadian Guideline on the Management of a Positive Human Papillomavirus Test and Guidance for Specific Populations. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5652-5679. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30060425

Zigras T, Mayrand M-H, Bouchard C, Salvador S, Eiriksson L, Almadin C, Kean S, Dean E, Malhotra U, Todd N, et al. Canadian Guideline on the Management of a Positive Human Papillomavirus Test and Guidance for Specific Populations. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(6):5652-5679. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30060425

Chicago/Turabian StyleZigras, Tiffany, Marie-Hélène Mayrand, Celine Bouchard, Shannon Salvador, Lua Eiriksson, Chelsea Almadin, Sarah Kean, Erin Dean, Unjali Malhotra, Nicole Todd, and et al. 2023. "Canadian Guideline on the Management of a Positive Human Papillomavirus Test and Guidance for Specific Populations" Current Oncology 30, no. 6: 5652-5679. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30060425