Abstract

Cancer care is evolving, and digital resources are being introduced to support cancer patients throughout the cancer journey. Logistical concerns, such as health literacy and the emotional experience of cancer, need to be considered. Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) and fear of cancer progression (FOP) are relevant emotional constructs that should be investigated. This scoping review explored two main objectives: first, the link between FCR/FOP and engagement with digital resources, and second, the link between FCR/FOP and health literacy. A database search was conducted separately for each objective. Relevant papers were identified, data were extracted, and a quality assessment was conducted. Objective 1 identified two relevant papers that suggested that higher levels of FCR were correlated with lower levels of engagement with digital resources. Objective 2 identified eight relevant papers that indicated that higher FCR/FOP is correlated with lower health literacy. However, one paper with a greater sample size and a more representative sample reported no significant relationship. There may be important relationships between the constructs of FCR/FOP, resource engagement, and health literacy and relationships may differ across cancer type and sex. However, research is limited. No studies examined the relationship between FOP and engagement or FCR/FOP and digital health literacy, and the number of studies identified was too limited to come to a firm conclusion. Further research is needed to understand the significance and relevance of these relationships.

1. Introduction

Modern cancer care is evolving rapidly. Earlier detection of cancer and improving treatment outcomes have resulted in increased survival with greater long-term healthcare needs [1]. The increased need for access to healthcare places a significant and increasing burden upon current healthcare systems [1]. Alternative solutions are required that reflect increasingly limited resources and encourage a new health model that moves away from a paternalistic system and instead helps patients take an active role in managing their long-term health [2]. This notion has led to an increase in digital health technologies and resources that are made available to individuals. Mobile-based, low-cost resources have been proposed as a crucial tool in lessening health spending and encouraging patients to take a more active role in their care [3]. The scope of these digital resources also ranges massively and can target different parts of the cancer care continuum, from prevention through treatment, symptom management, and survivorship [4].

However, for digital resources to be effective in supporting self-management, the barriers and facilitators to using them must be explored and understood from a patient perspective. The concerns that cancer patients report can include a lack of empowerment and support to use resources, digital incompatibility with their own technology, dislike of content, increased patient burden, difficulties using digital technology, low perceived usefulness, and the inability of digital interventions to replace interpersonal rapport [5,6]. Facilitators include cancer-specific information and communication with health care professionals, contact with fellow patients, symptom monitoring, real-time feedback, tailored information for personal goals, higher perceived usefulness, high usability, and age-appropriate design [5,6,7].

Additionally, an important consideration surrounding digital resources is digital health literacy. This combines two important concepts: health literacy and digital literacy. Health literacy refers to individuals possessing a level of knowledge, understanding, confidence, and the appropriate skills to access health information and services and, in turn, understand, evaluate, and use these services effectively [8]. Digital literacy can be outlined as the ability to access, manage, understand, and communicate information through digital technologies, as well as be able to evaluate this information safely and appropriately [9]. Together, these constructs describe the skills needed for an individual to effectively use digital health resources.

However, levels of health literacy and digital literacy differ among the population. In a cross-sectional survey measuring health literacy among British adults, 19.4% of participants expressed difficulty with written health information, and 23.2% faced challenges discussing health concerns with care providers [10]. For cancer patients, lower health literacy is associated with consequences such as an increased number of hospitalizations, greater emergency care requirements, increased uptake of preventative services, and limited understanding of health information and how to take medication properly [11]. Additionally, according to the 2023 Lloyds Consumer Digital Index Report [12], 25% of the UK population has the lowest digital capability and is likely to struggle when interacting with online services. Additionally, 2.1 million people are offline, and around 4.7 million cannot connect to Wi-Fi. Those with the lowest level of digital literacy are more likely to be over 70, express a lack of interest in online resources, are concerned about online fraud, and do not possess the necessary skills to limit their risk.

However, while these concerns focus on some of the logistical problems of implementing digital resources for cancer patients, it is essential to investigate the influence of the emotional experience of cancer on the use of digital resources as the approach to cancer care continues to evolve. When exploring the vast psychosocial consequences of cancer (e.g., sexual dysfunction [13], impact on employment status [14]), one issue of importance is fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) and fear of cancer progression (FOP). Although labeled separately, FCR and FOP are both concerned with patients’ fears around cancer either coming back, progressing, or metastasizing and share comparable defining features [15]. Therefore, for this review, FCR and FOP will be defined as ‘fear, worry, or concern relating to the possibility that cancer will come back or progress’ [16]. A recent meta-analysis examining the prevalence of FCR in cancer survivors and patients shows that 59% of cancer survivors and patients experience at least a moderate level of FCR, while 19% report a high level of FCR [17]. As rates of cancer survivorship increase, patients live longer while coping with their fears and uncertainties about cancer returning or progressing, making FCR/FOP a critical support need [18].

FCR/FOP can manifest in different ways depending on the individual. At some levels, these fears can be adaptive and encourage patient engagement with treatment, follow-up, and making healthy lifestyle changes [17]. However, excess FCR/FOP is associated with increased and excessive care seeking, hypervigilance around symptoms, or even withdrawal from healthcare, avoidance of appointments, and ignoring questionable symptoms [19]. Clinical levels of FCR can also limit patients’ quality of life and daily functioning [17]. FCR/FOP is a complicated and distressing experience for patients, and the nature of its manifestation means that it is likely to have a direct impact on the uptake of digital cancer resources—whether this is contributing to FCR/FOP through increased symptom checking and overuse of resources or the complete avoidance of resources as a potential trigger for heightened FCR/FOP.

FCR/FOP has been investigated to identify its potential risk factors and predictors. Studies have suggested that younger age, low mood, psychological issues (including anxiety and depression), lower levels of optimism, lower self-esteem, and denial and avoidance-oriented coping can act as predictors and risk factors for FCR [20]. These are important psychological considerations that may well influence patients’ uptake and engagement with digital resources. Furthermore, lower satisfaction in terms of understanding information, symptom management, and care co-ordination are also significant predictors of FCR [17]. Interestingly, these predictors appear to share some similarities with respect to health literacy and may be particularly important when encouraging patients to take an active role in their care using digital resources.

This scoping review has two main objectives. First, we aim to explore the relationship between FCR/FOP and uptake and engagement with digital resources, and second, the relationship between FCR/FOP, health literacy, and digital health literacy.

2. Materials and Methods

A scoping review method was used to explore the aims outlined above. This approach was chosen as it allowed for the exploration of study areas that do not appear to have been widely discussed or researched in the literature to date. A scoping review allowed for a general overview of what kind of research has been carried out so far, what some of the initial results indicate, the gaps in research that remain, and whether there is justification to continue research in these specific areas. The scoping review has not been registered.

2.1. Objective 1—What Is the Relationship Between FCR/FOP and Engagement with Digital Resources?

2.1.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies

For this scoping review, any studies published in a peer-reviewed journal were considered. Study design was not specified to ensure that any relevant studies that discuss the relationship between FCR/FOP and engagement with digital resources can be considered. The type of digital resource was not specified in the search protocol to open up the search to any study that may be relevant. However, it should be considered that most digital resources produced and then tested on a patient population are interventions aimed at improving some aspect of cancer patients’ lives (e.g., quality of life and mental well-being) [4].

Participants

Participants needed to be adults (over 18 years old) who have received a cancer diagnosis. Studies were included regardless of their own participant criteria, including cancer type, cancer stage, or participant demographics.

Outcome Measures

Any studies that reported a quantitative assessment of FCR or FOP levels and a measure of engagement with digital resources were considered for initial screening. In this case, the term engagement is used as an umbrella term to quantify the interaction with digital resources. Any outcomes that attempted to measure engagement with digital resources were considered. Measuring engagement is a multidimensional concept and may involve measures such as the number of logins, time spent logged in, time spent on different pages, pages viewed, meeting a minimum threshold of page views, etc. [21]. Studies were included in this review if they expressed that a specific outcome measured was engagement, regardless of how they specifically calculated this. Studies must then provide an analysis of the relationship between FCR/FOP levels and engagement with resources. This had to be clearly reported in the results section as the result of a quantitative analysis.

For this scoping review, we deemed it irrelevant whether FCR/FOP and engagement outcomes were primary or secondary as long as the relationship was reported.

2.1.2. Search Strategy

PubMed, Cochrane, and CINAHL were used as the primary databases for this search. The CINAHL integrated search was used and included APA PsycArticles, APA PsycINFO, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, and MEDLINE. Advanced search was used to input keywords and search titles and/or abstracts. No publication date was specified to ensure any relevant studies were identified. See Table 1 for Objective 1 search terms:

Table 1.

Search terms for Objective 1.

2.2. Objective 2: What Is the Relationship Between FCR/FOP and Health Literacy and Digital Health Literacy?

2.2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies

Once again, any studies published in a peer-reviewed journal were eligible for this review, and studies were not selected based on study design.

Participants

As outlined above for Objective 1.

Outcome Measures

Studies were considered if they reported a quantitative assessment of FCR/FOP and health literacy or digital health literacy. It was then essential that the study calculated and reported the relationship between FCR/FOP and health literacy or digital health literacy. Studies that reported both measures but did not calculate and report a relationship were excluded.

2.2.2. Search Strategy

PubMed, Cochrane, and CINAHL were the primary databases used. Once again, CINAHL searched APA PsycArticles, APA PsycINFO, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, and MEDLINE. No publication dates specified as focusing on both health literacy and digital health literacy opened up the search to both previous and contemporary studies focusing on these constructs. See Table 2 for search terms for Objective 2:

Table 2.

Search terms for Objective 2.

All papers retrieved by the search across the three databases were exported to a citation manager for screening. Duplicates were removed, and titles and abstracts were screened by one author (MK-J). Once this was completed, full text screening took place to identify relevant articles for the review that met inclusion criteria. In the case of Meng et al.’s [22] study, which was in the German language in the original article, we used an online translation tool and followed it with a German psychologist academic checking the translation for accuracy.

2.3. Quality Assessment

All studies included in the review were quality assessed using checklists from the Joanna Briggs Institute, depending on the study design. The checklists used were for analytical cross-sectional studies [23], cohort studies [24], and randomized controlled trials [25]. The checklists were of different lengths, and, therefore, studies were given a number based on the relevant aspects of the checklist. Quality assessments were reported in the data extraction tables, see Section 3.

3. Results

As this scoping review aimed to answer two separate research questions, the results of each search will be discussed and reported separately below.

3.1. What Is the Relationship Between FCR/FOP and Engagement with Digital Resources?

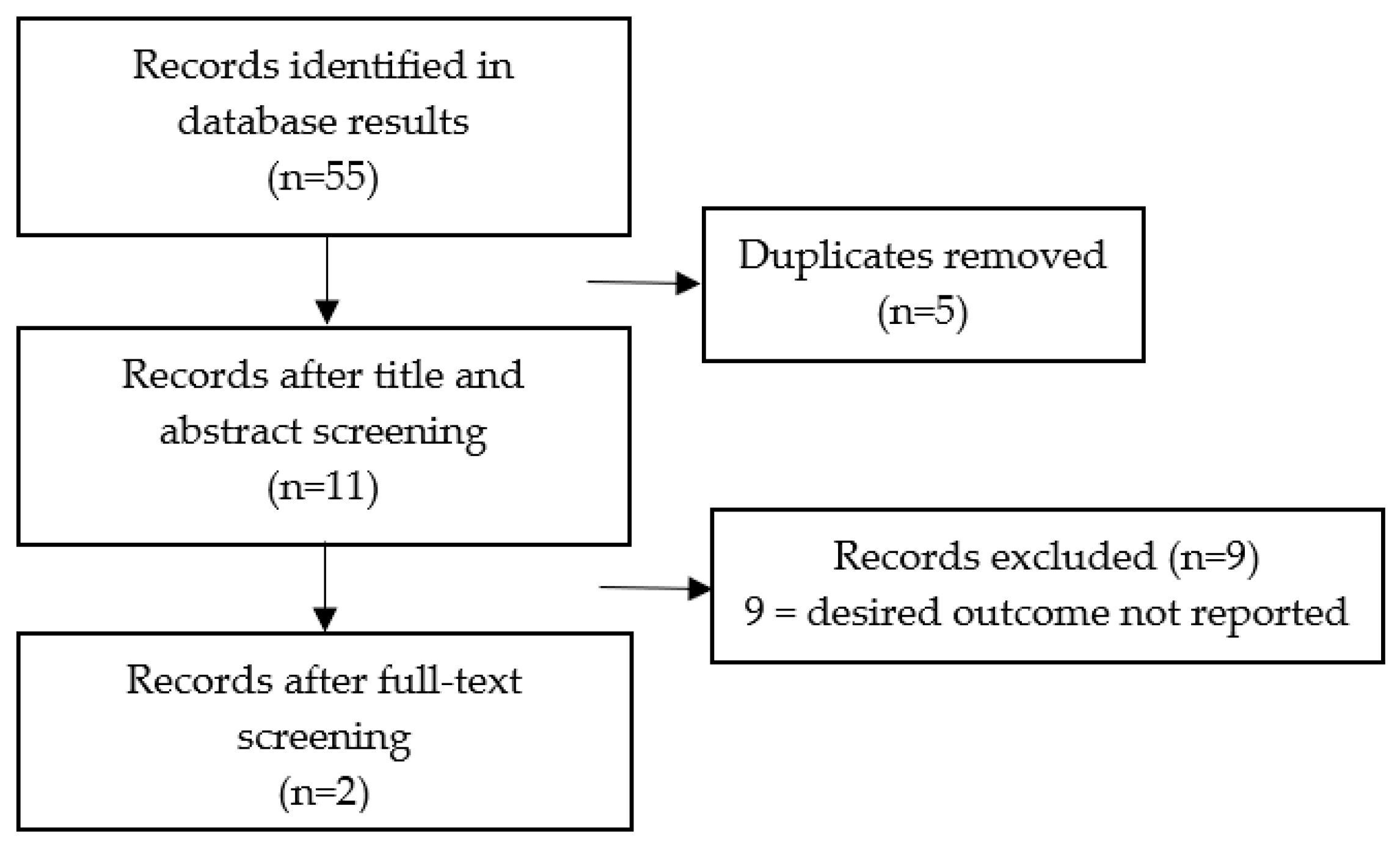

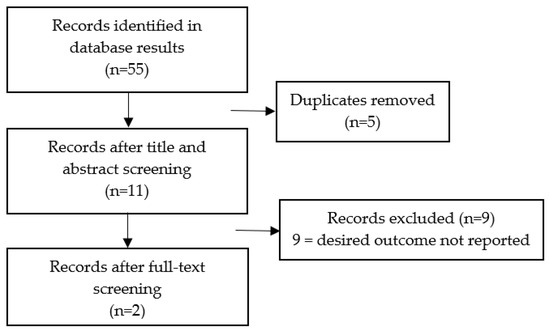

Figure 1 displays the screening process and outlines how many eligible papers were identified. Typically, although several papers used similar outcome measures, they did not calculate and report on the relationship between FCR/FOP and engagement, making them not usable in this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for Objective 1.

In total, only two papers provided data relevant to answering the research question (see Table 3). Both papers reported the relationship between FCR and engagement, but no papers were identified that reported the relationship between FOP and engagement. Despite this, there were significant differences between these papers. Smith et al. [26] conducted a repeated-measures cross-sectional survey study with a population of female breast cancer survivors. The sample size was small, with only 30 participants completing the intervention, and the primary aim of the study was to explore the feasibility and uptake of a digital resource aimed at reducing FCR. There were several outcomes measured, but the ones of interest for this review were uptake and engagement of the digital resource and FCR. The study outlined its own criteria for calculating uptake and engagement and classified participants into usage groups. FCR was measured using the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory Short-Form (FCRI-SF) [27]. This study aimed to identify any relevant correlates with engagement, which included calculating if there was any significant relationship between baseline FCR and engagement. Uptake was measured as the number of participants that agreed to take part in the study, and engagement was measured by grouping participants based on time spent using the resources, number of page views, and module/intervention completion. Results described a significant relationship between FCR and engagement, and participants were more likely to be grouped as low users if their baseline FCR was higher (OR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.004–1.585, p = 0.046). However, there was no reported calculation of any correlation between FCR and uptake of the resource.

Table 3.

Data extracted from search results Objective 1.

Cillessen et al. [28] also classified users based on engagement with the resource and used the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory [27] to measure FCR. Engagement was measured based on log data that reported time spent logged in and the number of assignments saved and submitted. This study also found that there was a significant relationship between usage and baseline FCR, with nonusers reporting increased baseline FCR (t 118 = 2.27, p = 0.03), and this was a medium to large effect (D = 0.69). FCR and adherence to the resource itself were also calculated but reported as non-significant, suggesting that FCR impacts the uptake/usage of a resource but not how well people adhere to the intervention once they have decided to use it.

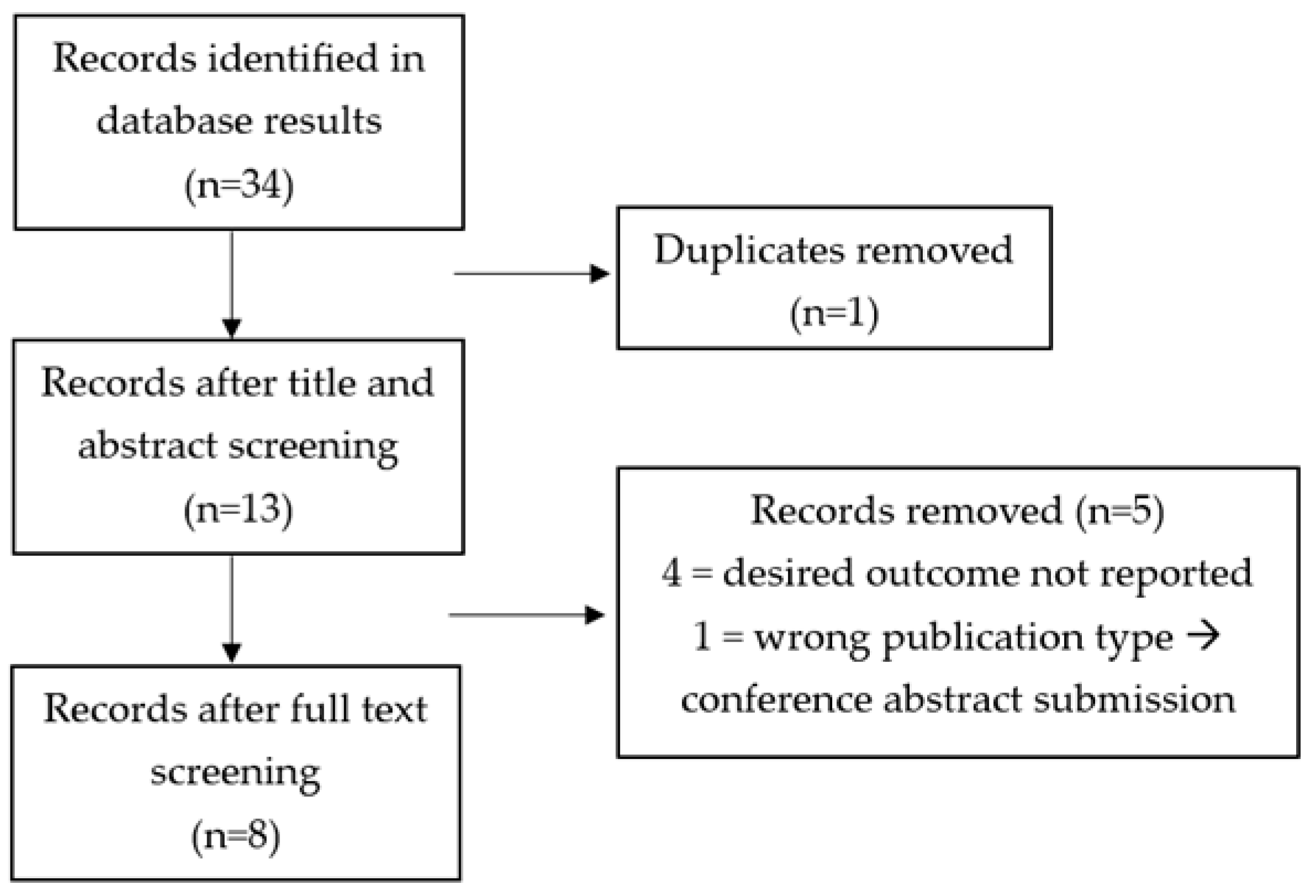

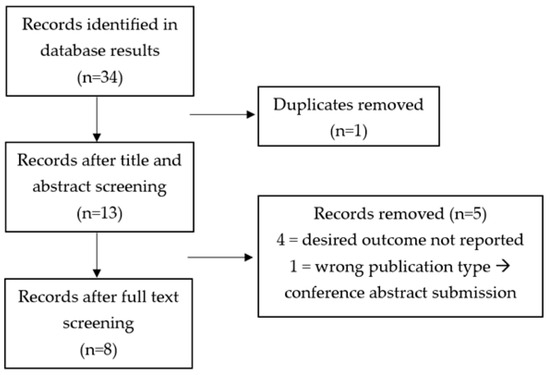

3.2. What Is the Relationship Between FCR and Health Literacy and Digital Health Literacy?

The screening process for this second search is displayed in Figure 2. Similarly to the first question, although papers used similar outcome measures, often there was no specific relationship calculated and reported between the constructs of interest and, therefore, many studies were deemed not usable.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flowchart for Objective 2.

Despite this, a total of eight papers were identified as relevant (see Table 4). These studies reported the relationship between FCR/FOP and health literacy. No studies reported the relationship between FCR/FOP and digital health literacy. The study design was similar across these papers, with five out of the eight conducting a cross-sectional survey study [29,30,31,32,33] and one study reporting the results from a secondary analysis of data retrieved from a cross-sectional survey study [34]. Two studies [22,35] reported on a prospective cohort study.

Table 4.

Data extracted from search results Objective 2.

Form NEO-FFI = NEO Five-Factor Inventory-3.

Sample size ranged quite significantly across all studies, from 155 participants in Tong et al.’s [31] study to 1749 participants in Zhang et al.’s [30] study. Participant eligibility also differed significantly between studies. There was a far greater number of female breast cancer patients recruited across the studies, but again, eligibility differed. For example, Halbach et al. [35] recruited newly diagnosed female breast cancer patients over the age of 65, Vandraas et al. [33] recruited female breast cancer survivors between the ages of 20 and 65, Tong et al. [31] recruited any female breast cancer patients over 18, Magnani et al. [34] focused on female cancer patients under age 55 that had been cancer-free for at least 5 years—although this study was open to any cancer type, over 80% of participants had been diagnosed with breast cancer, and Meng et al. [22] recruited both female and male participants, yet 63% of the sample were female and 53% were breast cancer patients. In contrast, Yang et al. [29] focused on male and female patients with advanced lung cancer. In this case, most participants (72.3%) were male. Clark et al. [32] recruited male and female head and neck cancer survivors, but 69% of participants were male. Zhang et al. [30] was the only study that recruited male or female cancer patients with any cancer type that had a more equal balance, with 54% being men. Additionally, Tong et al. [31] explored the influence of partner fears and, therefore, recruited only married women.

Further notable differences concern the outcomes measured across studies. Yang et al. [29], Zhang et al. [30], Tong et al. [31], Halbach et al. [35], and Meng et al. [22] focused on FOP rather than FCR and used the Fear of Progression Questionnaire—Short Form [36]. Clarke et al. [31], Vandraas et al. [32], and Magnani et al. [33] focused on FCR, but measures differed, with these studies using Fear of Relapse and Recurrence Scale [37], four items chosen from Concerns About Recurrence Scale [38], and a single-item screening question from the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory [27], respectively.

All studies measured health literacy, and no studies were identified that focused on digital health literacy and FCR/FOP. However, once again, measures differed. Zhang et al. [30] and Tong et al. [31] both used the Health Literacy Management Scale [39]. The other studies used the Health Literacy Scale for Patients with Chronic Disease [29], Brief Health Literacy Screen [30], European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire [35] and Single-Item Literacy Screener [34]. Vandraas et al. [33] used a 12-question version of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire Short-Form, and Meng et al. [22] used a six-question version.

Despite these differences across studies, seven out of eight reported the same relationship: greater levels of FCR/FOP are associated with lower levels of health literacy. Statistical analyses differed across studies (see Table 4 for details). The only study with a different result was Zhang et al. [30]. In this study, the relationship was not significant (beta = −0.01, p = 0.699). It is relevant to consider that this was the largest study and the only study that recruited both male and female participants, had a similar percentage of both male and female participants (54% male), and did not specify a cancer type.

4. Discussion

FCR and FOP are significant emotional challenges for people who have received a cancer diagnosis and undergone treatment. Addressing the fear of the cancer coming back or progressing is also often described as an unmet need by cancer patients [17]. Therefore, it is important that we fully understand these constructs to improve patients’ experiences and quality of life. This scoping review aimed to explore these constructs in the context of digital resources by exploring two relevant questions: (1) what is the relationship between FCR/FOP and uptake and engagement with digital resources?; (2) what is the relationship between FCR/FOP and health literacy and digital health literacy?

A thorough database search was conducted to identify eligible studies to answer these questions. However, despite how widely studied the impact of cancer is, very few studies have been conducted in these areas. Only two studies reported on the relationship between FCR/FOP and uptake and engagement, yet an important concept in understanding FCR/FOP is avoidance coping. This is a commonly reported method of dealing with fears around cancer [40]. Evidently, digital resources are ineffective without initial uptake and continued engagement. Therefore, it seems increasingly relevant to explore the effect FCR/FOP has on engagement, yet this search revealed only two studies reported on this.

Further research appears increasingly relevant when considering that both Smith et al. [26] and Cillessen et al. [28] reported that higher baseline FCR is significantly associated with lower usage of digital resources. In this case, both resources being tested were aimed at reducing FCR and general patient distress. Therefore, this provides no insight into any other type of resource, for example, symptom trackers, information websites, forums, and peer support. As cancer care continuously moves to involve technology and digital resources, there is the potential that patients’ needs may not be addressed by the changing digital system if their fears prevent them from engaging with digital resources.

It should also be noted that both studies had relatively small sample sizes (N = 30 [26] and N = 125 [28]), and the participant population was not representative of all cancer types. Smith et al. [26] focused specifically on breast cancer, whereas Cillessen et al. [28] did not specify a cancer type for involvement, but 60.8% of participants had breast cancer. Therefore, it is not possible to ascertain the effect of FCR on engagement according to different cancer types. Again, as we move toward an increasingly digital age, we must conduct representative studies to explore and understand the impact of this construct on all cancer types. Furthermore, it is important to mention that both studies measured FCR and give no insight into the impact of FOP or any relationships. Therefore, this currently indicates a gap in our understanding.

Similarly, the search into the relationship between FCR/FOP and health literacy and digital health literacy highlighted a lack of research in this area. No studies focused on digital health literacy, and only eight studies were relevant to the research question. There was a more even mix between examining FCR and FOP among these studies, with five of the studies studying FOP and three studying FCR. Out of these studies, seven reported a significant relationship between FCR/FOP and health literacy. This indicated that there was a relationship between health literacy and fears around cancer, whether this was measured as FOP or FCR. Lower levels of health literacy were associated with increased levels of FCR/FOP. However, with such a limited number of relevant studies, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions from these results. Again, this highlights the need to fully understand how these constructs are related, what this means for understanding both FCR/FOP, and how to potentially improve patient outcomes.

The only study that did not report a significant relationship between health literacy and FOP was Zhang et al. [30]. This study had the largest sample size, with 1749 participants, and recruited patients with any cancer type over the age of 18 and male or female (54% male). The finding that there was no relationship between health literacy and FOP in this large study suggests that perhaps there are other factors influencing the results in other studies. One factor that appears to stand out among the other seven studies is that four of them specifically focus on women with breast cancer [31,33,35] or women with any cancer, but the majority being breast cancer [34], and they all reported a significant relationship. Due to the lack of research in this area, it is not possible to suggest that cancer type or sex mediate the relationship between FCR/FOP and health literacy, but the question does emerge when exploring existing research.

Despite the lack of studies that explored and reported the relationships between FCR/FOP and engagement and FCR/FOP and health literacy, studies were of a relatively high quality. Studies used reliable and validated outcome measures, eligibility and measure of exposure (in this case, cancer) were made clear, and analyses were appropriate for the research question of each study. Some of the main limitations were a lack of generalizability, the difficulty establishing causality in a correlational analysis, a lack of clear direction to limit or resolve these issues, and a small number of studies identified in the review. Therefore, the results discussed in this scoping review reflect quality research and make these results increasingly compelling, but do also suggest further research is required to improve generalizability and contribute further evidence to understand the nature of the relationship between FCR/FOP, engagement, and health literacy.

Arguably, the greatest takeaway from this scoping review is that more research is needed. Cancer rates continue to increase worldwide, with the expected global burden to increase by 27 million new cases per year by 2040 [41], and the cancer demographic is changing, with recent research showing a 79% increase in the global incidence of early-onset cancer [42]. Therefore, as cancer care adapts and patients are encouraged to take a greater role in their long-term care, digital resources are being introduced as a way of supporting patients [43]. If this is to be a successful endeavor, emotional experiences like FCR and FOP need to be taken into account in the design process and implementation of these digital resources. The studies discussed above display that this is a necessary relationship to explore, and yet little research has been done.

To design effective digital resources in the future, it may be crucial to first understand how baseline FCR and FOP can impact engagement. Additionally, it appears there may be a significant relationship between health literacy and FCR/FOP, with the greatest evidence so far for breast cancer patients. Not only does this suggest another risk factor for FCR/FOP, but the closely linked construct of digital health literacy may also be a concern. None of the studies identified focused on digital health literacy. Therefore, this remains an unanswered question. However, as digital health literacy combines both digital and health literacy, it is an even more complex and important construct when discussing the implementation of digital cancer resources going forward.

Aside from the requirement for further research to provide stronger evidence for the relationships described in this review, it also appears it may be important to explore these in specific patient groups. To design and implement effective resources and provide meaningful and effective support, we must understand the influence of other factors such as sex, age, and cancer type on the relationships between FCR/FOP and engagement and health literacy, as well as identifying any potential relationship with digital health literacy, as well.

5. Conclusions

This review explored two research questions: (1) what is the relationship between FCR/FOP and uptake and engagement with digital resources?; (2) what is the relationship between FCR/FOP and health literacy and digital health literacy? There appears to be some evidence to suggest that there is a significant relationship between FCR/FOP and these constructs. It appears that increased FCR may be related to lower engagement with digital resources. Furthermore, it seems that increased FCR/FOP may be associated with lower levels of health literacy. However, data are limited. It is not possible to draw firm conclusions on these relationships at this point. There was no data available to explore FOP and engagement or FCR/FOP and digital health literacy.

Our scoping review shows that there is a clear gap in research, and these findings suggest this may be an increasingly important area to explore. Future research must explore FCR and FOP in these contexts to identify factors that should be considered going forward in improving cancer care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.O. and M.K.-J.; methodology, G.O. and M.K.-J.; formal analysis, G.O. and M.K.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.-J.; writing—review and editing, G.O., G.O., M.K.-J., P.N., and H.M.; supervision, G.O.; project administration, G.O. and M.K.-J.; funding acquisition, H.M., P.N. and G.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (NIHR200861). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the PETNECK2 Research Team, Ahmad Abou-Foul (Institute of Head and Neck Studies and Education, Department of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham) A.Abou-Foul@bham.ac.uk, Andreas Karwath (Department of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham) A.Karwath@bham.ac.uk, Ava Lorenc (QuinteT research group, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol) ava.lorenc@bristol.ac.uk, Barry Main (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Trust) B.G.Main@bristol.ac.uk, Claire Gaunt (Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit, University of Birmingham) C.H.Gaunt@bham.ac.uk, Colin Greaves (School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Birmingham) C.J.Greaves@bham.ac.uk, David Moore (Department of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham) D.J.MOORE@bham.ac.uk, Denis Secher (Patient Representative), Eila Watson (Oxford School of Nursing and Midwifery, Oxford Brookes University) ewatson@brookes.ac.uk, Georgios Gkoutos (Department of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham) G.Gkoutos@bham.ac.uk, Jane Wolstenholme (Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford) jane.wolstenholme@dph.ox.ac.uk, Janine Dretzke (Department of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham) J.Dretzke@bham.ac.uk, Jo Brett (Department of Midwifery, Community and Public Health, Oxford Brookes University) jbrett@brookes.ac.uk, Joan Duda (School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Birmingham) J.L.DUDA@bham.ac.uk, Julia Sissons (Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit, University of Birmingham) j.a.sissons@bham.ac.uk, Lauren Matheson (Oxford Institute of Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Research, Oxford Brookes University) l.matheson@brookes.ac.uk, Lucy Speechley (Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit, University of Birmingham) L.J.Speechley@bham.ac.uk, Marcus Jepson (QuinteT research group, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol) Marcus.jepson@bristol.ac.uk, Mary Wells (Nursing Directorate, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, Charing Cross Hospital) mary.wells5@nhs.net, Melanie Calvert (Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham) M.Calvert@bham.ac.uk, Pat Rhodes (Patient Representative), Philip Kiely (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust) Philip.Kiely@UHBristol.nhs.uk, Piers Gaunt (Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit, University of Birmingham) P.Gaunt@bham.ac.uk, Saloni Mittal (Institute of Head and Neck Studies and Education, Department of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham) s.mittal.2@bham.ac.uk, Steve Thomas (Bristol Dental School, University of Bristol) Steve.Thomas@bristol.ac.uk, Stuart Winter (Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford) Stuart.Winter@ouh.nhs.uk, Tessa Fulton-Lieuw (Institute of Head and Neck Studies and Education, Department of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham) m.t.fulton-lieuw@bham.ac.uk, Wai-lup Wong (East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust, Mount Vernon Cancer Centre) wailup.wong@nhs.net, Yolande Jefferson (Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit, University of Birmingham) y.c.jefferson@bham.ac.uk. We also thank Ines Jentzsch for helping us with checking the accuracy of the translation of the articles in this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hopstaken, J.S.; Verweij, L.; van Laarhoven, C.J.H.M.; Blijlevens, N.M.; Stommel, M.W.J.; Hermens, R.P.M.G. Effect of digital care platforms on quality of care for oncological patients and barriers and facilitators for their implementation: Systematic review. JMIR 2021, 23, e28869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciani, O.; Cucciniello, M.; Petracca, F.; Apolone, G.; Merlini, G.; Novello, S.; Pedrazzoli, P.; Zilembo, N.; Broglia, C.; Capelletto, E.; et al. Lung Cancer App (LuCApp) study protocol: A randomised controlled trial to evaluated a mobile supportive care app for patients with metastatic lung cancer. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardito, V.; Golubev, G.; Ciani, O.; Tarricone, R. Evaluating barriers and facilitators to the uptake of mHealth apps in cancer care using the consolidated framework for implementation research: Scoping literature review. JMIR Cancer 2023, 9, e42092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, K.; Turner, K.; Siwik, C.; Gonzalez, B.; Upasani, R.; Glazer, J.; Ferguson, R.; Joshua, C.; Low, C. Digital health and telehealth in cancer care: A scoping review of reviews. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; de Bruin, M.; Burton, C.D.; Bond, C.M.; Clausen, M.G.; Murchie, P. What are the current challenges of managing cancer pain and could digital technologies help? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 8, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, H.; Lipnick, D.; Diefenbach, M.A.; Posner, M.; Kotz, T.; Miles, B.; Genden, E. Development and usability testing of a web-based self-management intervention for oral cancer survivors and their family caregivers. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnan, S.; Aggarwal, S.; Mohammadi, L.; Koczwara, B. Barriers and enables of uptake and adherence to digital health interventions in older patients with cancer: A systematic review. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Improving Health Literacy to Reduce Health Inequalities. 2015. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/460709/4a_Health_Literacy-Full.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. A Global Framework of Reference on Digital Literacy Skills for Indicator 4.4.2. 2018. Available online: https://unevoc.unesco.org/home/TVETipedia+Glossary/show=term/term=Digital+literacy (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Simpson, R.M.; Knowles, E.; O’Cathain, A. Health literacy levels of British adults: A cross-sectional survey using two domains of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1819. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, C.E.; Wheelwright, S.; Harle, A.; Wagland, R. The role of health literacy in cancer care: A mixed studies systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyds Bank. Consumer Digital Index 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.lloydsbank.com/banking-with-us/whats-happening/consumer-digital-index.html (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Traa, M.J.; De Vries, J.; Roukema, J.A.; Den Oudsten, B.L. Sexual (dys)function and the quality of sexual life in patients with colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiemienti, M.; Morlino, G.; Ingravalle, F.; Vinci, A.; Colarusso, E.; De Santo, C.; Formosa, V.; Gentile, L.; Lorusso, G.; Mosconi, C.; et al. Unemployment status subsequent to cancer diagnosis and therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkel, A.; Herschbach, P. Fear of progression in cancer patients and survivors. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2018, 210, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebel, S.; Ozakinci, G.; Humphris, G.; Mutsaers, B.; Thewes, B.; Prins, J.; Dinkel, A.; Butow, P. From normal response to clinical problem: Definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3265–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luigjes-Huizer, Y.L.; Tauber, N.M.; Humphris, G.; Kasparian, N.A.; Lam, W.W.T.; Lebel, S.; Simard, S.; Smith, A.B.; Zachariae, R.; Afiyanti, Y.; et al. What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncol. 2022, 31, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, A.M.; Borneman, T.; Economou, D.; Cangin, M.A.; Patel, S.K.; Sharpe, L. Fear of cancer progression: Findings from case studies and a nurse-led intervention. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 24, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, L.E.; Siegel, S.D.; Duffy, N.M. Fear of cancer recurrence: A theoretical review and its relevance for clinical presentation and management. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, J.V.; Grunfeld, E.A. Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncol. 2013, 22, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Ainsworth, B.; Yardley, L.; Milton, A.; Weal, M.; Smith, P.; Morrison, L. A framework for analyzing and measuring usage and engagement data (AMUsED) in digital interventions: Viewpoint. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, K.; Hess, V.; Schulte, T.; Faller, H.; Schuler, M. The impact of health literacy on health outcomes in cancer patients attending inpatient rehabilitation. Thieme 2021, 60, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI. Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. JBI: Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- JBI. Checklist for Cohort Studies. JBI: Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomised controlled trials. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Bamgboje-Ayodele, A.; Jegathees, S.; Butow, P.; Klein, B.; Salter, M.; Turner, J.; Fardell, J.; Thewes, B.; Sharpe, L.; et al. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of iConquerFear: A self-guided digital intervention for fear of cancer recurrence. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, 18, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simard, S.; Savard, J. Fear of cancer recurrence inventory: Development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support. Care Cancer 2008, 17, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cillessen, L.; van de Ven, M.; Compen, F.; Bisseling, E.; van der Lee, M.; Speckens, A. Predictors and effects of usage of an online mindfulness intervention for distressed cancer patients: Usability study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Qin, H. The relationships among symptom experience, family support, health literacy, and fear of progression in advanced lung cancer patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 3549–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Deng, J.; Yi, D.; Chen, J. The effect of health literacy, self-efficacy, social support and fear of disease progression on the health-related quality of life of patients with cancer in China: A structural equation model. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2023, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L. Prevalence and factors contributing to fear of recurrence in breast cancer patients and their partners: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Women’s Health 2024, 16, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Dunne, S.; Coffey, L.; Sharp, L.; Desmond, D.; O’Conner, J.; O’Sullivan, E.; Timon, C.; Cullen, C.; Gallagher, P. Health literacy impacts self-management, quality of life and fear of recurrence in head and neck cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandraas, K.; Reinertsen, K.; Kiserud, C.; Bohn, S.; Lie, H. Health literacy among long-term survivors of breast cancer; exploring associated factors in a nationwide sample. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7587–7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, C.; Smith, A.; Rey, D.; Sarradon-Eck, A.; Preau, M.; Bendiane, M.; Bouhnik, A.; Mancini, J. Fear of cancer recurrence in young women 5 years after diagnosis with a good-prognosis cancer: The VICAN-5 national survey. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 17, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbach, S.; Enders, A.; Kowalski, C.; Pfortner, T.; Pfaff, H.; Wesslemann, S.; Ernstmann, N. Health literacy and fear of cancer progression in elderly women newly diagnosed with breast cancer–a longitudinal analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnert, V.A.; Herschbach, P.; Berg, P.; Henrich, G.; Koch, U. Fear of progression questionnaire–short form (FoP-Q-SF). APA PsycTests 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.; Kornblith, A.; Herndon, J.; Zuckerman, E.; Schiffer, C.; Weiss, R.; Mayer, R.; Wolchok, S.; Holland, J. Quality of life for adult leukemia survivors treated on clinical trails of cancer and leukemia group B during the period 1971–1988: Predictors for later psychologic distress. Cancer 1997, 80, 1936–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, B.; Zachariae, R.; Christensen, S.; Nielsen, T.; Butow, P. The concerns about recurrence questionnaire: Validation of a brief measure of fear of cancer recurrence amongst Danish and Australian breast cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Buchbinder, R.; Briggs, A.; Elsworth, G.; Busija, L.; Batterham, R.; Osborn, R. The health literacy management scale (HeLMS): A measure of an individual’s capacity to seek, understand and use health information within the healthcare setting. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 91, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, D.; Wang, Z.; Qin, N. Triggers and coping strategies for fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 9501–9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). World Cancer Report 2020; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-92-832-0447-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, L.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Yuan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Larsson, S.; Tsilidis, K.; Dunlop, M.; et al. Global trends in incidence, death, burden and risk factors of early-onset cancer from 1990 to 2019. BMJ Oncol. 2023, 2, e000049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, A. Utilizing the advances in digital health solutions to manage care in cancer patients. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 6, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).