Abstract

Background: A cancer diagnosis and its treatment often disrupt a child’s and adolescent’s normal level of physical activity, which plays a vital role in their development and health. They are therefore often less physically active during treatment than before the diagnosis or compared to healthy peers. Today, there is no comprehensive overview of the safety, feasibility, clinical effectiveness, and potentially long-lasting impact of physical activity (PA) interventions in this population. Methods: We conducted a systematic review in PubMed according to PRISMA guidelines to evaluate studies on PA interventions during cancer treatment in children and adolescents up to 25 years of age. We used the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tools to assess the risk of bias. Due to the heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes, we used descriptive approaches only to present the results. Results: Half of the 21 included studies were randomized controlled trials (10/21). PA interventions were found to be safe and feasible when tailored to the patient’s age, treatment phase, and clinical condition. Most studies reported improvements in physical fitness, strength, and quality of life, with some reductions in fatigue. Variability in interventions and outcomes, along with small sample sizes and heterogeneous patient populations, made it difficult to draw clear conclusions. Conclusions: PA appears to be a feasible and, in terms of injuries, safe adjunct to cancer treatment in children and adolescents. Despite promising trends, further large-scale, multicenter trials with standardized protocols are needed to better establish the long-term benefits and optimal interventions.

1. Introduction

Childhood cancer remains a significant global health challenge, with over 400,000 new cases diagnosed annually worldwide [1]. Survival has improved dramatically over the last few decades due to improvements in diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care [2]. However, it still is a life-altering diagnosis that affects not only the physical health of young patients but also their emotional well-being, social development and overall quality of life (QoL). The treatment remains challenging, often marked by fatigue, physical deconditioning, and other physical and mental side effects [3,4]. These challenges are compounded by the fact that cancer treatment often disrupts a child’s normal routines, including physical activity, which plays a vital role in their development and health [5,6,7]. The reduction in physical activity and the resulting inactive and sedentary lifestyle can be caused by treatment-related side effects such as fatigue, pain, general malaise, and decreased physical function. Such inactivity may exacerbate side effects and negatively impact physical and mental health. Therefore, interventions that promote physical activity in children and adolescents during treatment may counteract these effects and support their development and QoL [7,8]. These interventions correspond to exercises, equivalent to structured and regular activities as part of overall physical activity.

Current research highlights the potential benefits of physical activity during cancer treatment, even when adapted to the physical limitations imposed by the cancer or its treatment. Therefore, offering physical activity may be an opportunity to support children and adolescents in their recovery and to improve their quality of life. Studies suggest that tailored physical activity programs can help to reduce treatment related fatigue, improve cardiorespiratory fitness and physical functioning, and enhance overall QoL [9,10,11]. While it may seem counterintuitive to encourage activity during such a physically demanding time, carefully monitored exercise programs have been shown to improve physical fitness, muscle strength, and overall well-being in children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer [12,13]. These interventions showed high adherence rates, suggesting that children and their families are willing to participate in structured physical activity programs during treatment [10].

Despite these promising findings, the role of physical activity during cancer treatment in children and adolescents remains underexplored. There is limited consensus on which type, duration, and intensity of activities are effective, the optimal intervention designs, the outcomes to be measured, safety parameters, and feasibility across diverse patient populations.

This systematic review aims to (1) assess the impact of physical activity interventions on physical, psychological, and functional outcomes in children and adolescents treated for cancer, (2) to identify barriers and facilitators to implement physical activity interventions in pediatric oncology settings, (3) to determine the safety and feasibility of physical activity interventions, and (4) to provide inputs for future research to optimize the integration of physical activity into standard cancer care protocols for children.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14]. Inclusion criteria were defined using the PICO framework: (P) The population of interest comprised children, adolescents, and young adults diagnosed with any type of cancer up to the age of 25 years and still under treatment at initiation of the intervention. (I) The intervention was defined as any physical activity intervention (e.g., aerobic, stretching, yoga, and/or exergaming). (C) Comparator were given by the original study and included cancer patients without intervention, own comparison by pre and post intervention, active control groups with different activities than the intervention group, or historical cohorts. (O) The primary outcomes were the impact of physical activity interventions on physical and functional outcomes. The secondary outcomes were the impact of physical activity interventions on mental health, QoL, and possible adverse events of the interventions. Eligible study designs had to include comparators (e.g., randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), cross-over, cluster randomized trial).

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across PubMed/MEDLINE, including studies published between January 2000 and May 2024. An additional evidence search was performed using reference screening of identified (systematic) reviews and guidelines/recommendations. The search strategy combined subject headings (e.g., MeSH terms) and keywords of the following concepts: “children”, “cancer”, “physical activity/exercise training/therapy”, and “during treatment” (Supplementary Table S1).

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

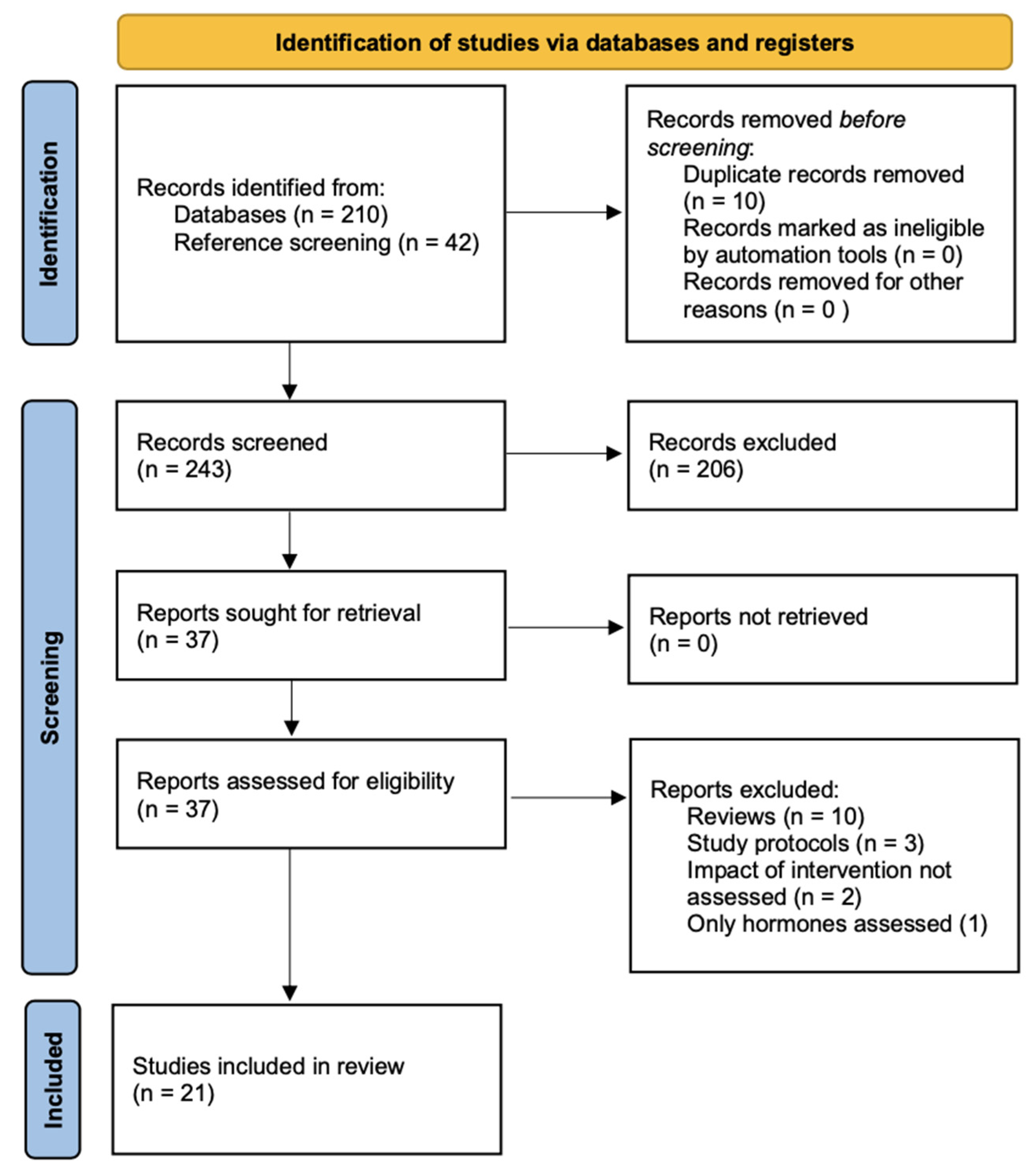

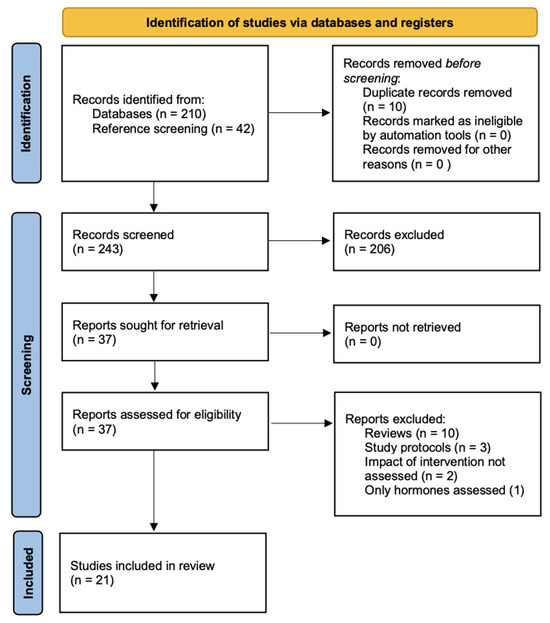

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers using predefined eligibility criteria. Potential publications from the reference screening were included in the title and abstract screening too. Full-text articles were reviewed for studies that met the eligibility criteria. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer. The study selection process was documented using a PRISMA flow diagram.

Data were extracted from eligible studies into a standardized data sheet, including information on the first author, publication year, study design, patient characteristics, type of interventions, and outcomes.

2.4. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias was assessed independently by two reviewers using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tools (https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools, accessed 1 May 2024) appropriate for each study type. We used tools for RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, and cohort studies. As the tools do not categorize studies by quality, we established a grading system (low, medium, and high quality). Thirteen aspects were assessed for RCTs. We defined high quality as 12 or 13 fulfilled aspects, medium quality as 10 or 11 fulfilled aspects, and low quality as ≤9 fulfilled aspects. Quasi-experimental studies assessed nine aspects: high quality as 8 or 9 fulfilled aspects and medium quality as 6 or 7 fulfilled aspects. The cohort study assessed eleven aspects.

2.5. Analysis

Based on the literature review that we performed before we carried out this systematic review, we assumed that the interventions, the tests to assess the outcomes, the start and intervals of the outcome assessment, and the reporting of the results would be heterogeneous. Therefore, we decided to focus on the outcomes rather than the interventions, as the improvement in outcomes is ultimately the clinically relevant aspect. Based on the assumed heterogeneity, it was not possible to perform meta-analyses or to draw forest plots, and the results are presented descriptively only. Also due to the heterogeneity, we reported the results as significant if it was stated that way in the original publication. If one group performed better that the other, but not statistically significant, we stated it as “trend”. For the readability of the tables, we further did not include the exact result by reporting it as a confidence interval, standard error, or p-value, for example. These exact results are available in the Supplementary Material Excel S1. This systematic review is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024551543). Therefore, no review protocol was prepared.

3. Results

The literature search identified 210 publications. A further 42 publications were added through reference screening, 206 publications were excluded at screening level, and 37 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Among these, 21 met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Half of the included studies were RCTs (10/21), the other half were quasi-experimental studies (10/21), and one was a pre-post cohort study (Table 1). Ten studies examined acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients only. The number of analyzed patients per study ranged from 8 to 170. The quality of the studies included was medium and high in 16 studies (Table 1, Supplemental Table S2). The main aspects resulting in down-grading were that blinding of participants and those who delivered the intervention was not possible or because it was unclear if some aspects were considered in the studies but not reported or were not considered (Supplemental Table S2).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the 21 included studies.

3.1. Summary of Interventions

The spectrum of reported physical activity interventions was heterogeneous. We summarized the interventions into five broader categories: (1) physical activity interventions covering aerobic exercise, strength or weight-bearing exercises, and endurance training [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], (2) less intensive interventions focusing on stretching, short-burst high-intensity exercises or separate hand or leg function [26,27,28], (3) aerobic exercise only [29], (4) exergaming [30,31,32], (5) yoga [33], and (6) coaching alone [34] (Table 2). Half of the included studies belong to the first category. If mentioned, the duration of the interventions ranged from 3 weeks to 135 weeks (Table 2). Most of the interventions took completely or partially place in the inpatient setting (15/21 studies), and were mostly given as individual sessions and not as group sessions (Table 2). In most studies, the comparators were patients receiving usual care (12/21 studies) or healthy matched controls (5/21 studies), and less frequently the patient itself (e.g., pre- and post-intervention comparisons), or controls receiving general instructions on benefit of physical activity (Table 2). Safety and feasibility were assessed in 15 of the 21 studies and it could be confirmed in all 15 studies with no study reporting accidents or adverse events (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of the interventions, interval from diagnosis to intervention, and time of outcome assessment in the 21 included studies.

3.2. Summary of Outcomes

Based on the reported outcomes, we defined the following six outcome categories: (1) cardiopulmonary fitness, (2) muscle strength, (3) physical activity, (4) physical performance, (5) quality of life (QoL) and (6) other outcomes. The outcomes reported in the eligible studies and assigned to each of these categories are summarized in Table 3. The time points of outcome assessments are summarized in Table 2. The spectrum of tests and reported parameters to assess the outcomes was very broad. We therefore only report the most frequent ones in the manuscript, but all tests, outcomes, and effect sizes are reported in the Supplementary Material Excel S1.

Table 3.

Overview of the six outcome categories.

3.2.1. Physical Performance

Eleven studies examined a component of physical performance (Table 4). The Timed Up and Go test (TUG) was used most frequently, followed by the Timed Up and Down Stairs test (TUDS), the 6 min walk test (6-MWT), and the Sit to Stand test.

Table 4.

Results of included studies reporting on physical performance.

In half of the studies (5/11), patients in the intervention group either significantly improved their physical performance over time or they performed better than controls [18,22,32,33,35]. Additional four studies showed a trend towards improvement in the intervention group over time or compared to controls [17,20,27,35] (Table 4). Thorsteinsson could show a biphasic course with a decline during treatment and an improvement thereafter [23].

3.2.2. Quality of Life (QoL)

Eleven studies examined QoL. Two studies showed no significant difference between intervention and control groups in a cross-sectional comparison of health-related QoL up to 135 weeks of follow-up [15,16]. The same was found for fatigue, behavioral problems, and depressive symptoms.

All eleven studies examined changes in QoL over time—from baseline to different points of follow up (Table 3). Three studies showed an improvement in general QoL in both groups over time [15,17,33], whereas two studies showed no significant difference [27,29]. The results were very heterogeneous in the fatigue subscale. One study reported an increase in fatigue scores in both groups [15], one reported no change in both groups [30] and three an improvement in the intervention group [25,32,34] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of included studies reporting on quality of life.

3.2.3. Physical Activity

Ten studies assessed physical activity. The pattern of change in physical activity between the intervention and control group and within each group over time were very heterogeneous (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of included studies reporting on physical activity.

Only the results by Kowaluk et al. showed significant differences between the intervention and control groups in the short-term, where patients from the intervention group were more physically active, reported in the HBSC questionnaire [31]. Contrary, three studies showed no significant differences in the short- or long-term assessment between both groups [15,30,31], including Kowaluk et al. with no significant difference in the long-term [31]. Looking at changes in physical activity over time, only Fiuza-Luce and Masoud et al. reported a significant increase over time in the intervention group [17,32], with two additional studies reporting a trend towards an increase in the intervention group [16,35]. The interventions in these four studies included circuits including aerobic and weight-bearing exercises, video games, and an exercise program not further specified (Table 2). Two studies reported a larger increase in the control group [17,30].

3.2.4. Muscle Strength

Nine studies examined muscle strength, looking into different muscle groups and thus using different tests to assess the effect of the interventions (Table 7). Grip strength, knee extension, and ankle dorsiflexion were examined in three studies each. Four studies assessed combinations of multiple tests over time (e.g., upper and lower body muscle strength, 5-repetition maximum). No assessment was used twice. Muscle strength significantly increased in five studies, from baseline to last follow-up. The underlying interventions in these five studies were aerobic and weight-bearing circuits [15,17,21,22] and a combination of stretching, strengthening, and aerobic fitness [27] (Table 2).

Table 7.

Results of included studies reporting on muscle strength.

3.2.5. Cardiopulmonary Fitness

Six studies examined cardiopulmonary fitness and performed cardiopulmonary exercise tests (CPET). Peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) was the only parameter assessed in all six studies. No study could show a significant difference between the intervention and control group. The same was true for differences within each group over time. However, four studies showed a trend towards improvement in VO2peak in the intervention group (Table 8). The interventions in these studies were aerobic and weight-bearing/muscle strength circuits with or without balance exercise [17,18,20] and interactive videogaming [31] (Table 2).

Table 8.

Results of included studies reporting on cardiopulmonary fitness.

3.2.6. Other Outcomes

Four studies assessed flexibility, three assessed motor performance and one assessed acute toxicities using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

Among other parameters, flexibility was assessed in all studies using active or passive ankle dorsiflexion. Dorsiflexion decreased in two studies over time [16,26] remained stable and increased in one study each [27,33]. The decrease could be measured in the intervention and control group in both studies, with the second assessment at 135 weeks and 2 years, respectively (Table 9). The examined population were leukemia patients in both studies.

Table 9.

Results of included studies reporting on other outcomes.

Motor performance was assessed by four different test batteries. None of the three studies reported a significant difference in motor performance between the intervention and control group. Hartman et al. reported a trend towards improvement over time in the overall cohort, but no difference between both groups [26]. Contrary, the performance decreased over time in both groups combined in the study by Hamari et al.; again, with no difference between both groups (Table 9) [30]. Both studies had a follow-up of at least one year. The interventions differed with exergaming in one and exercise program, including stretching and short-burst high-intensity elements in the other study (Table 2).

Munise et al. reported their results on acute toxicities descriptively only [19]. The 8-week individualized program consisted of aerobic, resistance, and flexibility exercise and resulted in a reduction in severe fatigue in the intervention group (Table 5). The outcome was assessed after 10 weeks (Table 2).

4. Discussion

In this systematic review of studies on physical activity interventions during cancer treatment in children and adolescents, we identified 21 publications. We could identify six different categories of interventions: (1) physical activity sessions covering aerobic exercise, strength or weight-bearing exercises, and endurance, (2) less intensive physical activity sessions focusing on stretching, short-burst high-intensity exercises or separate hand or leg function, (3) aerobic exercise only, (4) exergaming, (5) yoga, and (6) coaching alone. We further identified six categories how the impact of physical activity can be assessed: (1) cardiopulmonary fitness, (2) muscle strengths, (3) physical activity level, (4) physical performance, (5) quality of life, and (6) other outcomes. These categories highlight the broad and heterogeneous spectrum used today. The clinically important aspects regarding physical activity interventions in this patient population include feasibility, adverse events, and clinical impact.

4.1. Feasibility of Physical Activity Interventions

Results from this systematic review show that physical activity interventions for children and adolescents undergoing cancer treatment are both safe and feasible. In support of this, 15 out of 21 studies confirmed the safety and feasibility of engaging in physical activity during cancer treatment.

Another systematic review by Grimshaw et al. (2016) came to the same conclusion by analyzing 11 quantitative and 1 qualitative study, concluding that such interventions were acceptable to both children and their parents, and could be successfully implemented in hospital settings [36]. Another example that physical activity during treatment is both feasible and beneficial is the ActiveOncoKids network in Germany. They aim to provide exercise opportunities for pediatric oncology patients throughout their treatment journey [37]. A significant achievement of ActiveOncoKids is the development of consensus-based guidelines for implementing movement and exercise interventions in pediatric oncology. These guidelines offer eleven recommendations addressing the importance of exercise during treatment, program design, safety considerations, and strategies to overcome barriers to participation. They emphasize that exercise interventions should be tailored to individual patient needs, considering factors such as physical and mental impairments, inactivity levels, and clinical restrictions [38].

Despite the promising evidence, several barriers to implementing physical activity interventions remain [39]. Individual factors such as the child’s physical condition, treatment side effects, psychological state, and type of physical activity can influence participation. Environmental or family factors can have an impact too. Logistical challenges may include scheduling of the sessions in general and being flexible if the actual health status does not allow physical activity or the activity needs to be adapted at short notice. Lastly, institutional barriers may exist, such as the availability of resources (space and manpower) and recognizing the necessity of such interventions regarding the economic thinking and the fear of too high costs and expenses. Addressing these barriers requires a tailored approach that considers individual patient needs and local circumstances.

4.2. Feasibility of Outcome Assessment

Studies have demonstrated that assessing physical fitness, functional capacity, and QoL in this population is feasible; however, logistical and methodological barriers remain. Factors influencing the feasibility of outcome assessment and the participants’ ability to engage in assessments at consistent and predefined time points include: (1) the heterogeneity of treatment protocols with different intensity of the treatment administered and different intervals between phases of intensive treatment and phases of recovery, (2) the disease severity, and (3) the age of the child or adolescent. Various assessment tools, such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing, six-minute walk tests, and different strength measurements, have been successfully implemented in research settings. Other assessments proved to be less feasible. For example, Thorsteinsson et al. excluded the modified Andersen test from their test battery, as they deemed the test not compatible in children with cancer and it was not possible to rate the fitness as with VO2peak [23]. Despite these challenges, research has shown that outcome assessments can be integrated into clinical and rehabilitation programs with appropriate modifications. For instance, the study by Caru et al. demonstrated the feasibility of a multidisciplinary physical activity program in pediatric oncology, reporting an adherence rate of about 40% despite hospital-specific restrictions and organizational conflicts [40]. While assessing outcomes in physical activity interventions for children and adolescents with cancer during therapy is feasible, it requires careful consideration of methodological and logistical challenges. Addressing these challenges through innovative approaches and standardized protocols will enhance the quality and applicability of future research in this field.

4.3. Adverse Events

The findings of our systematic review underscore the feasibility of integrating physical activity programs into oncology care without posing additional risks to patients. This is consistent with results from other studies that have shown that physical activity in children and adolescents with cancer undergoing treatment is considered safe [7,41]. The absence of reported injuries or negative effects suggests that these interventions can be safely implemented when appropriately designed and monitored. A key factor contributing to the safety of these programs is their individualized approach [6]. In all studies, interventions have been carefully adapted to patients’ age, physical capability, and clinical status, ensuring that activities are neither excessively demanding nor detrimental to their health. This personalized approach accounts for the varying degrees of treatment-related fatigue, immunosuppression, and other side effects that may impact a child’s ability to participate. Some studies even took the thrombocyte count into account and reduced or omitted intense sessions when the counts were too low [42]. Additionally, supervised sessions led by trained professionals further enhance safety by allowing for real-time adjustments based on each patient’s condition [6]. While the current evidence supports the safety of physical activity during cancer treatment, this topic was not mentioned in all studies included in this systematic review, and future studies should continue to monitor potential risks systematically. Standardized safety reporting across studies will be essential to further validate these findings and optimize intervention protocols.

4.4. Clinical Impact of Physical Activity Interventions

Based on the results of our systematic review, physical activity interventions have demonstrated physical and psychological benefits for children and adolescents undergoing cancer treatment. Engaging in structured exercise programs has been associated with improvements in physical fitness, muscle strength, and functional mobility, which are often compromised due to the effects of chemotherapy, radiation, and prolonged hospital stays [7]. This systematic review showed the largest amount of improvement in cardiopulmonary fitness, physical performance, and muscle strength.

While many studies report beneficial effects, it is important to note that improvements are not always significantly larger in intervention compared to the control group. Some studies, including some of this review, observed positive changes in both groups. For example, Braam et al. showed an increase in cardiopulmonary fitness in both groups [15]. Possible reasons for this observation could be that the initial shock of the diagnosis and feeling insecure in the new situation contribute to a decline in physical activity in general. Following this initial phase and when patients become more familiar with the new situation, they automatically become more active again. This might explain the improvement not only in the intervention, but also in the control group. The observation that improvements in the intervention group are not always significantly better than in controls could be explained by the rather small samples examined. In addition, children are generally less frail than adults and might cope better with phases of reduced activity or inactivity. Natural maturation and aging may also be another possible cause of improvement over time for both groups.

The same as for physical fitness could also be shown for quality of life, where three studies have shown that there was an improvement in the intervention and control group [15,17,33]. Again, this may be due to natural recovery processes, variations in usual care, or the influence of other supportive therapies. Additionally, the clinical impact of physical activity interventions remains limited by small study populations and variations in study protocols, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

4.5. Aspects for the Future

While existing research supports the feasibility, safety, and potential benefits of physical activity interventions in children and adolescents with cancer, several important aspects remain to be addressed in future studies. One key area is the need for larger, multicenter randomized controlled trials to strengthen the evidence. Many current studies are limited by small sample sizes, short intervention durations, and heterogeneous study designs, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the long-term clinical impact of physical activity. Understanding the optimal type, intensity, and duration of physical activity interventions will be key to maximizing their impact on clinical outcomes. Future research should focus on standardized protocols to ensure comparability and reproducibility of findings across different patient populations and treatment settings. Furthermore, future research should investigate personalized approaches to exercise prescription. Given the variability in cancer types, treatment regimens, and individual patient conditions, tailoring physical activity interventions based on specific needs and treatment phases may optimize their effectiveness. Studies should explore how different intensities, frequencies, and modalities of exercise impact various patient subgroups to develop more individualized recommendations. Lastly, the current evidence allows no conclusion on whether the interventions have a long-lasting impact on physical activity adherence or whether they have an impact on physical activity levels once the intervention is terminated. The duration of the intervention in the reported studies was very broad and ranged from 3 to 135 weeks. In terms of the impact of the interventions, the outcomes were assessed in most studies during or shortly after the end of the intervention. The longest follow-up was two years after the intervention in one study. Therefore, future studies should also investigate the aspect of long-lasting effects and whether the level of physical activity might also have an impact on other social aspects (e.g., employment),

4.6. Strength and Limitations

A significant strength of this review is its robust methodological approach. The screening and data extraction process was conducted by two independent reviewers, ensuring thorough and unbiased selection of studies. In cases of disagreement, a third independent reviewer was involved to make the final decision, enhancing the reliability of the study selection process. This systematic and transparent approach minimized the risk of selection bias and improved the overall quality of the review. Furthermore, a detailed quality assessment of the included studies was performed, evaluating the internal and external validity of the studies. This process helped ensure that the studies included in the review were both reliable and relevant to the research question. The quality assessment allowed for a critical evaluation of the studies’ methodologies and their ability to provide meaningful insights into the clinical impact and safety of physical activity interventions in pediatric oncology.

Despite these strengths, several limitations must be acknowledged. Searching PubMed as the only database could be considered a limitation. However, reference secreening of identified (systematic) reviews and guidelines/recommendations was performed. One major limitation is the large variety of interventions and outcome measures used across the studies. This diversity made it difficult to draw clear and definitive conclusions regarding the effectiveness of physical activity interventions. The lack of consistency in outcome measures prevented the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis, which could have provided a more comprehensive summary of the evidence. The variation in interventions, including different exercise regimens, intensities, and duration, and outcome measures also complicated direct comparisons between studies. As a result, it was not possible to determine the superiority or inferiority of specific physical activity interventions. For the same reason, it was also not possible to examine differences bewteen different types of cancer. Additionally, many studies included small sample sizes and heterogeneous patient populations, which limited the generalizability of the results. The lack of statistical power often led to the reporting of only trends or small effects, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Some studies even reported results descriptively without statistical analyses, further limiting the ability to evaluate the true impact of physical activity interventions on health outcomes in this population.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, physical activity interventions for children and adolescents undergoing cancer treatment have been shown to be both safe and feasible, but few studies were shown to be significantly effective. While most studies report improvements in the intervention groups, similar effects were also observed in control groups. A key limitation remains the small sample sizes in existing studies, which restrict the generalizability of findings. These limitations highlight the need to perform controlled studies, as it will be impossible to estimate the effect of the intervention witout assessing the natural change. Despite these challenges, physical activity can be endorsed as a beneficial component of pediatric oncology care. Further research is essential to assess the long-term impact and sustainability of these interventions to optimize their effectiveness and implementation in clinical practice. Future studies should focus on identifying and mitigating barriers, tailoring interventions to individual needs, and integrating behavior change techniques to promote sustained engagement in physical activity during and after cancer treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol32040234/s1, Table S1: Search strategy; Table S2: Quality assessment; Excel S1: comprehensive overview over all outcomes, including separate sheets on “Characteristics”, “Intervention Outcome1”, “Intervention Outcome2”, “Cardiopulmonary fitness”, “Physical performance”, “Motor performance”, “Physical activity”, “Muscle strength”, “QoL”, “Balance and coordination”, and “Flexibility”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.B., K.S. and M.O. Methodology: N.B., K.S. and M.O. Data extraction and formal analysis: N.B., K.L., H.O., E.J.V., P.H. and M.O. Writing—original draft preparation: N.B. Writing—review and editing: K.L., S.V.K., D.M.-B., H.O., A.O., S.M.F.P., E.S., E.J.V., P.H., K.S. and M.O. Funding acquisition: K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation (HSR-5219-11-2020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALL | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary exercise test |

| CPM | Counts per minute |

| GLTEQ | Godin-Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire |

| GCLTPAQ | Godin-Shepard leisure time physical activity questionnaire |

| HBSCQ | Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Questionnaire |

| MET | Metabolic equivalent |

| MVPA | Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PedsQL | Pediatric Quality of life Inventory; |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| TUDS | Timed Up and Down Stairs test |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go tests |

| VO2peak | Peak oxygen uptake |

| 6-MWT | 6 min walk test |

| 5-RM 10-RM | Maximum strength capacity to perform five/ten repetitions until muscular exhaustion/fatigue |

References

- Ward, Z.J.; Yeh, J.M.; Bhakta, N.; Frazier, A.L.; Girardi, F.; Atun, R. Global childhood cancer survival estimates and priority-setting: A simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdmann, F.; Frederiksen, L.E.; Bonaventure, A.; Mader, L.; Hasle, H.; Robison, L.L.; Winther, J.F. Childhood cancer: Survival, treatment modalities, late effects and improvements over time. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 71, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer in Children; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hamner, T.; Latzman, R.D.; Latzman, N.E.; Elkin, T.D.; Majumdar, S. Quality of life among pediatric patients with cancer: Contributions of time since diagnosis and parental chronic stress. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, S.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Conyers, R.; Shields, N. Promoting positive physical activity behaviors for children and adolescents undergoing acute cancer treatment: Development of the CanMOVE intervention using the Behavior Change Wheel. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 980890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, E.; Gokal, K.; Kettle, V.E.; Daley, A.J. Effects of physical activity interventions on physical activity and health outcomes in young people during treatment for cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2023, 9, e001466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapti, C.; Dinas, P.C.; Chryssanthopoulos, C.; Mila, A.; Philippou, A. Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity Levels on Childhood Cancer: An Umbrella Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, K.I.; van der Torre, P.; Takken, T.; Veening, M.A.; van Dulmen-den Broeder, E.; Kaspers, G.J. Physical exercise training interventions for children and young adults during and after treatment for childhood cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 3, Cd008796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, F.T.; Bloch, W.; Beulertz, J. Clinical exercise interventions in pediatric oncology: A systematic review. Pediatr. Res. 2013, 74, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.S.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Rincón-Castanedo, C.; Takken, T.; Fiuza-Luces, C.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Lucia, A. Exercise training in childhood cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 70, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsie, C.; Ebert, J.; Joske, D.; Ackland, T. The Benefit of Physical Activity in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients During and After Treatment: A Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2019, 8, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurz, A.; McLaughlin, E.; Lategan, C.; Ellis, K.; Culos-Reed, S.N. Synthesizing the literature on physical activity among children and adolescents affected by cancer: Evidence for the international Pediatric Oncology Exercise Guidelines (iPOEG). Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, K.I.; van Dijk-Lokkart, E.M.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; Takken, T.; Huisman, J.; Buffart, L.M.; Bierings, M.B.; Merks, J.H.M.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Veening, M.A.; et al. Effects of a combined physical and psychosocial training for children with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.L.; Zhu, L.; Kaste, S.C.; Srivastava, K.; Barnes, L.; Nathan, P.C.; Wells, R.J.; Ness, K.K. Modifying bone mineral density, physical function, and quality of life in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e26929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiuza-Luces, C.; Padilla, J.R.; Soares-Miranda, L.; Santana-Sosa, E.; Quiroga, J.V.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Lorenzo-González, R.; Verde, Z.; et al. Exercise Intervention in Pediatric Patients with Solid Tumors: The Physical Activity in Pediatric Cancer Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridh, M.K.; Schmidt-Andersen, P.; Andrés-Jensen, L.; Thorsteinsson, T.; Wehner, P.S.; Hasle, H.; Schmiegelow, K.; Larsen, H.B. Children with cancer and their cardiorespiratory fitness and physical function-the long-term effects of a physical activity program during treatment: A multicenter non-randomized controlled trial. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 19, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsie, C.; Ebert, J.; Joske, D.; Collins, J.; Ackland, T. The potential impact of exercise upon symptom burden in adolescents and young adults undergoing cancer treatment. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.K.F.; Christensen, J.F.; Frandsen, T.L.; Thorsteinsson, T.; Andersen, L.B.; Christensen, K.B.; Wehner, P.S.; Hasle, H.; Adamsen, L.; Schmiegelow, K.; et al. Effects of a physical activity program from diagnosis on cardiorespiratory fitness in children with cancer: A national non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perondi, M.B.; Gualano, B.; Artioli, G.G.; de Salles Painelli, V.; Filho, V.O.; Netto, G.; Muratt, M.; Roschel, H.; de Sá Pinto, A.L. Effects of a combined aerobic and strength training program in youth patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2012, 11, 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- San Juan, A.F.; Fleck, S.J.; Chamorro-Viña, C.; Maté-Muñoz, J.L.; Moral, S.; García-Castro, J.; Ramírez, M.; Madero, L.; Lucia, A. Early-phase adaptations to intrahospital training in strength and functional mobility of children with leukemia. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsteinsson, T.; Larsen, H.B.; Schmiegelow, K.; Thing, L.F.; Krustrup, P.; Pedersen, M.T.; Christensen, K.B.; Mogensen, P.R.; Helms, A.S.; Andersen, L.B. Cardiorespiratory fitness and physical function in children with cancer from diagnosis throughout treatment. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2017, 3, e000179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, C.C.; Müller, C.; Hardes, J.; Gosheger, G.; Boos, J.; Rosenbaum, D. The effect of individualized exercise interventions during treatment in pediatric patients with a malignant bone tumor. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Man Wai, J.P.; Lin, U.S.; Chiang, Y.C. A pilot study to examine the feasibility and effects of a home-based aerobic program on reducing fatigue in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Nurs. 2011, 34, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, A.; te Winkel, M.L.; van Beek, R.D.; de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S.M.; Kemper, H.C.; Hop, W.C.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Pieters, R. A randomized trial investigating an exercise program to prevent reduction of bone mineral density and impairment of motor performance during treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2009, 53, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, V.G.; Chiarello, L.A.; Lange, B.J. Effects of physical therapy intervention for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2004, 42, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriens, A.; Verschueren, S.; Vanrusselt, D.; Troosters, T.; Gielis, M.; Dirix, V.; Vanderhenst, E.; Sleurs, C.; Uyttebroeck, A. Physical fitness throughout chemotherapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and lymphoma. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodashenas, E.; Badiee, Z.; Sohrabi, M.; Ghassemi, A.; Hosseinzade, V. The effect of an aerobic exercise program on the quality of life in children with cancer. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2017, 59, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, L.; Järvelä, L.S.; Lähteenmäki, P.M.; Arola, M.; Axelin, A.; Vahlberg, T.; Salanterä, S. The effect of an active video game intervention on physical activity, motor performance, and fatigue in children with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowaluk, A.; Woźniewski, M. Interactive Video Games as a Method to Increase Physical Activity Levels in Children Treated for Leukemia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, A.E.; Shaheen, A.A.M.; Algabbani, M.F.; AlEisa, E.; AlKofide, A. Effectiveness of exergaming in reducing cancer-related fatigue among children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2224048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurz, A.; Chamorro-Vina, C.; Guilcher, G.M.; Schulte, F.; Culos-Reed, S.N. The feasibility and benefits of a 12-week yoga intervention for pediatric cancer out-patients. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 1828–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooke, M.C.; Hoelscher, A.; Tanner, L.R.; Langevin, M.; Bronas, U.G.; Maciej, A.; Mathiason, M.A. Kids Are Moving: A Physical Activity Program for Children With Cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 36, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyer-Mileur, L.J.; Ransdell, L.; Bruggers, C.S. Fitness of children with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia during maintenance therapy: Response to a home-based exercise and nutrition program. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2009, 31, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, S.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Shields, N. The Feasibility of Physical Activity Interventions During the Intense Treatment Phase for Children and Adolescents with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götte, M.; Söntgerath, R.; Gauß, G.; Wiskemann, J.; Buždon, M.; Kesting, S. A National Implementation Approach for Exercise as Usual Care in Pediatric and Adolescent Oncology: Network ActiveOncoKids. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 34, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götte, M.; Gauß, G.; Dirksen, U.; Driever, P.H.; Basu, O.; Baumann, F.T.; Wiskemann, J.; Boos, J.; Kesting, S.V. Multidisciplinary Network ActiveOncoKids guidelines for providing movement and exercise in pediatric oncology: Consensus-based recommendations. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götte, M.; Kesting, S.; Winter, C.; Rosenbaum, D.; Boos, J. Experience of barriers and motivations for physical activities and exercise during treatment of pediatric patients with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caru, M.; Duhamel, G.; Marcil, V.; Sultan, S.; Meloche, C.; Bouchard, I.; Drouin, S.; Bertout, L.; Laverdiere, C.; Sinnett, D.; et al. The VIE study: Feasibility of a physical activity intervention in a multidisciplinary program in children with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saultier, P.; Vallet, C.; Sotteau, F.; Hamidou, Z.; Gentet, J.C.; Barlogis, V.; Curtillet, C.; Verschuur, A.; Revon-Riviere, G.; Galambrun, C.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents with Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesting, S.; Weeber, P.; Schönfelder, M.; Pfluger, A.; Wackerhage, H.; von Luettichau, I. A Bout of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) in Children and Adolescents during Acute Cancer Treatment-A Pilot Feasibility Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).