A Novel GPPAS Model: Guiding the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care Utilising Collaboration between General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Results

2.1. Key Outcomes of the Studies Contributing Evidence for the Development of the GPPAS Model

2.2. Key Problems and Quality Improvement Strategies Informing the GPPAS Model Components

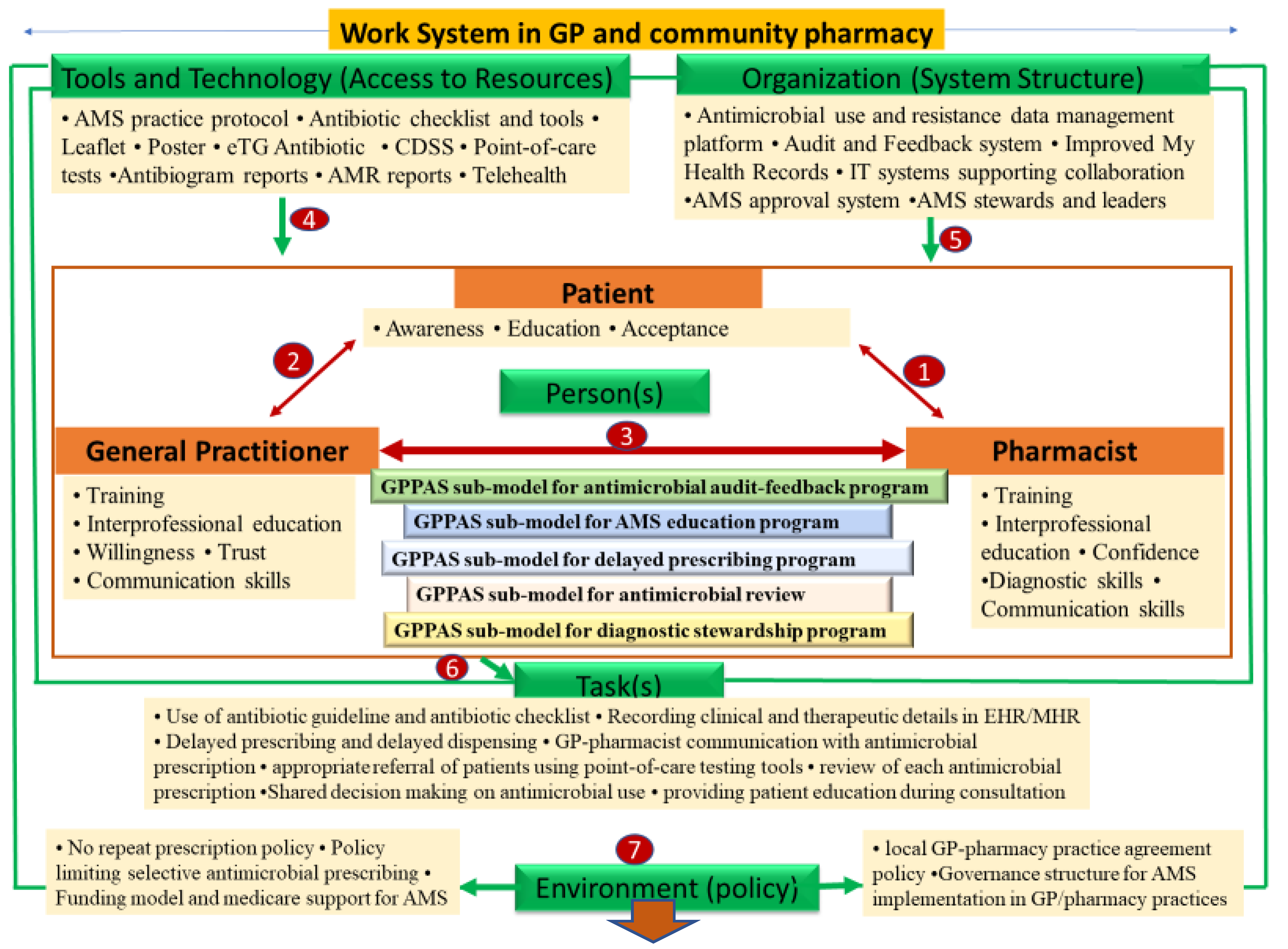

2.3. GPPAS Implementation Model Framework: Design, Discussion, and Implications

2.3.1. GPPAS Component 1: Pharmacist-Patient Interactions

2.3.2. GPPAS Component 2: GP-Patient Interactive Communication

2.3.3. GPPAS Component 3: GP-Pharmacist Collaboration

GPPAS Implementation Submodel for Antimicrobial Audits and Feedback Programmes

GPPAS Implementation Submodel for AMS Educational Programmes

GPPAS Implementation Submodel for Delayed Prescribing Programmes

GPPAS Implementation Submodel for Review of Antimicrobial Prescriptions

GPPAS Implementation Submodel for Diagnostic Antimicrobial Stewardship

2.3.4. GPPAS Component 4: Tools and Technology (Access to Resources)

2.3.5. GPPAS Component 5: Organisational Support (System Structures)

2.3.6. GPPAS Component 6: Tasks

2.3.7. GPPAS Component 7: Policy Environment

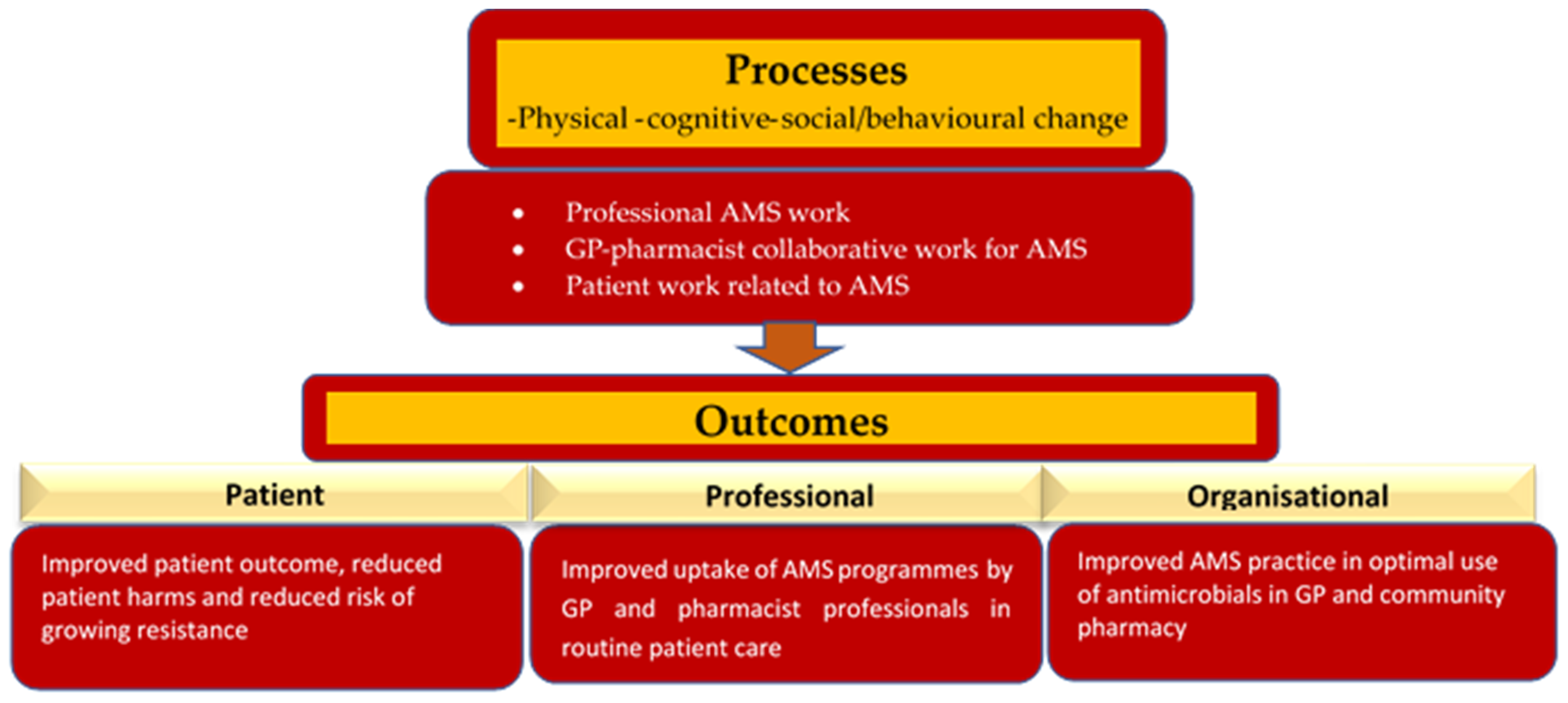

2.3.8. GPPAS Implementation Process and Outcomes

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

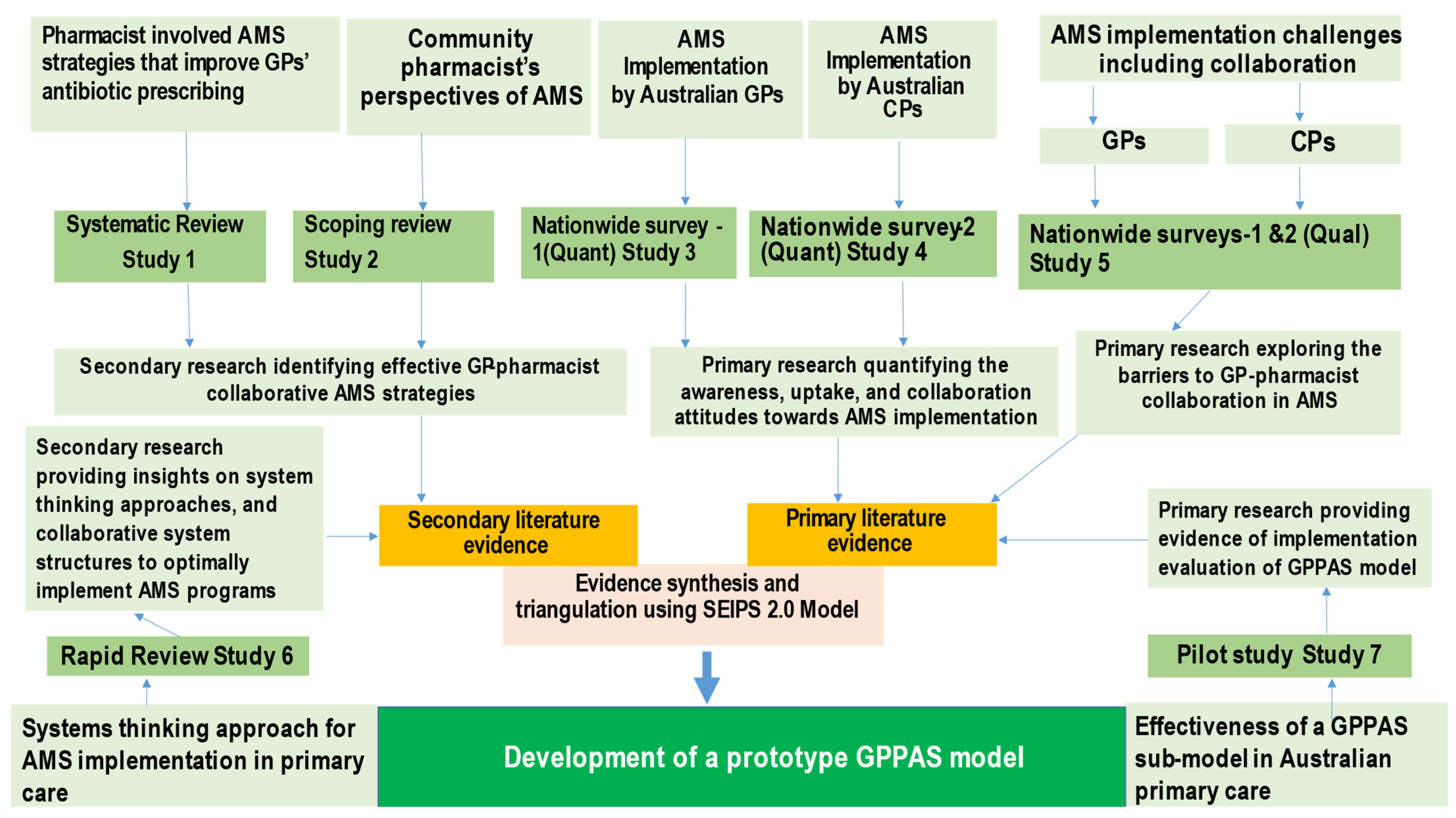

5. Methods

5.1. Theoretical Model Selection

5.2. Evidence Synthesis and Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial Resistance and Primary Health Care; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326454/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.56-eng.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Costelloe, C.; Metcalfe, C.; Lovering, A.; Mant, D.; Hay, A.D. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010, 18, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.Y.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Martinez, E.M.; Pant, S.; Gandra, S.; Levin, S.A.; Goossens, H.; Laxminarayan, R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvale, G.; Embrett, M.; Razavi, S.D. ‘Gearing Up’ to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care: A systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charani, E.; Holmes, A.H. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes: The need for wider engagement. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyar, O.J.; Beović, B.; Vlahović-Palčevski, V.; Verheij, T.; Pulcini, C. How can we improve antibiotic prescribing in primary care? Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2016, 14, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepser, M.E.; Adams, A.J.; Klepser, D.G. Antimicrobial stewardship in outpatient settings: Leveraging innovative physician pharmacist collaborations to reduce antibiotic resistance. Health Secur. 2015, 13, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossialos, E.; Courtin, E.; Naci, H.; Benrimoj, S.; Bouvy, M.; Farris, K.; Noyce, P.; Sketris, I. From “retailers” to health care providers: Transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy 2015, 119, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Health Care Facilities in Low- and Middle- Income Countries. A WHO Practical Toolkit; World Health Organissation (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329404/9789241515481-eng.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. The Pharmacy Contribution to Antimicrobial Stewardship. 2017. Available online: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Policy/AMS%20policy.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Bishop, C.; Yacoob, Z.; Knobloch, M.J.; Safdar, N. Community pharmacy interventions to improve antibiotic stewardship and implications for pharmacy education: A narrative overview. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, L.; Gauthier, T.; Heil, E.; Klepser, M.; Kelly, K.M.; Nailor, M.; Wei, W.; Suda, K.; Outpatient Stewardship Working Group. The essential role of pharmacists in antibiotic stewardship in outpatient care: An official position statement of the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2018, 58, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Hawes, L.; Mazza, D. Effectiveness of interventions involving pharmacists on antibiotic prescribing by general practitioners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepser, M.E.; Klepser, D.G.; Dering-Anderson, A.M.; Morse, J.A.; Smith, J.K.; Klepser, S.A. Effectiveness of a pharmacist-physician collaborative program to manage influenza-like illness. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2016, 56, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papastergiou, J.; Trieu, C.R.; Saltmarche, D.; Diamantouros, A. Community pharmacist–directed point-of-care group A Streptococcus testing: Evaluation of a Canadian program. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2018, 58, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Doble, A.; Thornley, T.; Saei, A.; Gold, N.; Sallis, A.; McNulty, C.A.; Lecky, D.; Umoh, E.; Klinger, C. Improving Management of Respiratory Tract Infections in Community Pharmacies and Promoting Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Cluster Randomised Control Trial with a Self-Report Behavioural Questionnaire and Process Evaluation. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawes, L.; Buising, K.; Mazza, D. Antimicrobial Stewardship in General Practice: A Scoping Review of the Component Parts. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essack, S.; Pignatari, A.C. A framework for the non-antibiotic management of upper respiratory tract infections: Towards a global change in antibiotic resistance. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2013, 67, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, R.M.; de Vries, M.J.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S. Collaboration in chronic care: Unpacking the relationship of pharmacists and general medical practitioners in primary care. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 19, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.F. Pharmacist-led home medicines review and residential medication management review: The Australian model. Drugs Aging 2016, 33, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Barton, C.; Promite, S.; Mazza, D. Knowledge, Perceptions and Practices of Community Pharmacists Towards Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Systematic Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Kong, D.; Thursky, K.; Mazza, D. A Nationwide Survey of Australian General Practitioners on Antimicrobial Stewardship: Awareness, Uptake, Collaboration with Pharmacists and Improvement Strategies. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Kong, D.C.; Thursky, K.; Mazza, D. Antimicrobial stewardship by Australian community pharmacists: Uptake, collaboration, challenges, and needs. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Kong, D.C.M.; Thursky, K.; Mazza, D. Divergent and Convergent Attitudes and Views of General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists to Collaboratively Implement Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Australia: A Nationwide Study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.K.; Kong, D.C.; Mazza, D.; Thursky, K. A system thinking approach for antimicrobial stewardship in primary care. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neels, A.J.; Bloch, A.E.; Gwini, S.M.; Athan, E. The effectiveness of a simple antimicrobial stewardship intervention in general practice in Australia: A pilot study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACSQHC. Role of the Pharmacist and Pharmacy Services in Antimicrobial Stewardship. 2018. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/Chapter11-Role-of-the-pharmacist-and-pharmacy-services-in-antimicrobial-stewardship.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Gilchrist, M.; Wade, P.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Howard, P.; Sneddon, J.; Whitney, L.; Wickens, H. Antimicrobial stewardship from policy to practice: Experiences from UK antimicrobial pharmacists. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2015, 4, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, L.; Lau, E.; Spinks, J. The Management of Urinary Tract Infections by Community Pharmacists: A State-Wide Trial: Urinary Tract Infection Pharmacy Pilot-Queensland (Outcome Report). 2022. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/232923/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Wickens, H.J.; Farrell, S.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.A.I.; Jacklin, A.; Holmes, A.; Antimicrobial Stewardship Group of the Department of Health Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Health Care Associated Infections (ASG-ARHAI); Cooke, J.; Sharland, M.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; McNulty, C.; et al. The increasing role of pharmacists in antimicrobial stewardship in English hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 2675–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.F.; Owens, R.; Sallis, A.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Thornley, T.; Francis, N.A.; Butler, C.; McNulty, C.A. Qualitative study using interviews and focus groups to explore the current and potential for antimicrobial stewardship in community pharmacy informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework. BMJ Open. 2018, 8, e025101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, D.M.; Morton, J. Role of the pharmacist in antimicrobial stewardship. Med. Clin. 2018, 102, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essack, S.; Bell, J.; Shephard, A. Community pharmacists—Leaders for antibiotic stewardship in respiratory tract infection. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2018, 43, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, M.; Wisner, K.; Lee, F. Community pharmacists and antimicrobial stewardship—What is their role? J. Med. Optimis. 2017, 3, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Van Duijn, H.J.; Kuyvenhoven, M.M.; Schellevis, F.G.; Verheij, T.J. Illness behaviour and antibiotic prescription in patients with respiratory tract symptoms. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2007, 57, 561–568. [Google Scholar]

- Altiner, A.; Brockmann, S.; Sielk, M.; Wilm, S.; Wegscheider, K.; Abholz, H.H. Reducing antibiotic prescriptions for acute cough by motivating GPs to change their attitudes to communication and empowering patients: A cluster-randomized intervention study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, T.; Trochez, C.; Thomas, R.; Babar, M.; Hesso, I.; Kayyali, R. Knowledge and awareness of the general public and perception of pharmacists about antibiotic resistance. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altiner, A.; Knauf, A.; Moebes, J.; Sielk, M.; Wilm, S. Acute cough: A qualitative analysis of how GPs manage the consultation when patients explicitly or implicitly expect antibiotic prescriptions. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Rhodes, A.; Cranswick, N.; Downes, M.; O’Hara, J.; Measey, M.A.; Gwee, A. A nationwide parent survey of antibiotic use in Australian children. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher-Lartey, S.; Yee, M.; Gaarslev, C.; Khan, R. Why do general practitioners prescribe antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections to meet patient expectations: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, P.; Pitceathly, C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2002, 325, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paskovaty, A.; Pflomm, J.M.; Myke, N.; Seo, S.K. A multidisciplinary approach to antimicrobial stewardship: Evolution into the 21st century. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shallcross, L.; Lorencatto, F.; Fuller, C.; Tarrant, C.; West, J.; Traina, R.; Smith, C.; Forbes, G.; Crayton, E.; Rockenschaub, P.; et al. An interdisciplinary mixed-methods approach to developing antimicrobial stewardship interventions: Protocol for the Preserving Antibiotics through Safe Stewardship (PASS) Research Programme. Wellcome Open Res. 2020, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plachouras, D.; Hopkins, S. Antimicrobial stewardship: We know it works; time to make sure it is in place everywhere. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; p. ED000119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodicka, T.A.; Thompson, M.; Lucas, P.; Heneghan, C.; Blair, P.S.; Buckley, D.I.; Redmond, N.; Hay, A.D. Reducing antibiotic prescribing for children with respiratory tract infections in primary care: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e445–e454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuningham, W.; Anderson, L.; Bowen, A.C.; Buising, K.; Connors, C.; Daveson, K.; Martin, J.; McNamara, S.; Patel, B.; James, R.; et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in remote primary healthcare across northern Australia. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.W.; Johnson, K.M.; Pham, S.N.; Egwuatu, N.E.; Dumkow, L.E. Implementing outpatient antimicrobial stewardship in a primary care office through ambulatory care pharmacist-led audit and feedback. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, e246–e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerhof, L.R.; Dumkow, L.E.; Hanrahan, T.L.; McPharlin, S.V.; Egwuatu, N.E. Outcomes of an ambulatory care pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship program within a family medicine resident clinic. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 42, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, G.L.; Wacogne, I.D. UK recommendations for combating antimicrobial resistance: A review of ‘antimicrobial stewardship: Systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use’(NICE guideline NG15, 2015) and related guidance. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2018, 103, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A.L.; Seaton, R.A.; Cooper, M.A.; Hedderwick, S.; Goodall, V.; Reed, C.; Sanderson, F.; Nathwani, D. Good practice recommendations for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in adults in the UK: A consensus statement. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIDRAP. Pocket Guide for Antibiotic Pharmacotherapy. 2022. Available online: https://ochsner-craft.s3.amazonaws.com/www/static/Antibiotic_Pocket_Guide.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Van Katwyk, S.R.; Jones, S.L.; Hoffman, S.J. Mapping educational opportunities for healthcare workers on antimicrobial resistance and stewardship around the world. Hum. Resour. Health 2018, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, M.; Lim, R.; Castro-Sanchez, E.; Deslandes, R.; Hodson, K.; Morris, G.; Reeves, S.; Weiss, M.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Bain, H.; et al. Development of consensus-based national antimicrobial stewardship competencies for UK undergraduate healthcare professional education. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 100, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Santiago, V.; Marwick, C.A.; Patton, A.; Davey, P.G.; Donnan, P.T.; Guthrie, B. Time series analysis of the impact of an intervention in Tayside, Scotland to reduce primary care broad-spectrum antimicrobial use. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welschen, I.; Kuyvenhoven, M.M.; Hoes, A.W.; Verheij, T.J. Effectiveness of a multiple intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract symptoms in primary care: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2004, 329, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalva, G.; Fernández-Urrusuno, R.; Turmo, J.M.; Hernández-Soto, R.; Pajares, I.; Carrión, L.; Vázquez-Cruz, I.; Botello, B.; García-Robredo, B.; Cámara-Mestres, M.; et al. Long-term impact of an educational antimicrobial stewardship programme in primary care on infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the community: An interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurling, G.K.P.; Del Mar, C.B.; Dooley, L.; Foxlee, R. Delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 4, CD004417. [Google Scholar]

- de la Poza Abad, M.; Dalmau, G.M.; Bakedano, M.M.; González, A.I.G.; Criado, Y.C.; Anadón, S.H.; del Campo, R.R.; Monserrat, P.T.; Palma, A.N.; Ortiz, L.M.; et al. Prescription strategies in acute uncomplicated respiratory infections: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høye, S.; Gjelstad, S.; Lindbæk, M. Effects on antibiotic dispensing rates of interventions to promote delayed prescribing for respiratory tract infections in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e777–e786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Avent, M.L.; Fejzic, J.; van Driel, M.L. An underutilised resource for antimicrobial Stewardship: A ‘snapshot’ of the community pharmacists’ role in delayed or ‘wait and see’ antibiotic prescribing. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 26, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakeena, M.; Bennett, A.A.; McLachlan, A.J. Enhancing pharmacists’ role in developing countries to overcome the challenge of antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, E.P.; Page, K.; Whitty, J.A.; Doust, J.; Graves, N. Antibiotic prescribing in primary healthcare: Dominant factors and trade-offs in decision-making. Infect. Dis. Health 2018, 23, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkin-Crine, S.; Yardley, L.; Little, P. Antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections in primary care: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, J.; Goossens, H.; Schedler, M.; Sefton, A.; Sessa, A.; van der Velden, A. Factors influencing inappropriate antibiotic prescription in Europe. Educ. Prim. Care 2013, 24, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.A.; Perez, K.K.; Forrest, G.N.; Goff, D.A. Review of rapid diagnostic tests used by antimicrobial stewardship programs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, S134–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minejima, E.; Wong-Beringer, A. Implementation of rapid diagnostics with antimicrobial stewardship. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2016, 14, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, D.A.; Jankowski, C.; Tenover, F.C. Using rapid diagnostic tests to optimize antimicrobial selection in antimicrobial stewardship programs. Pharmacotherapy 2012, 32, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, R.; Wu, T.; Wei, X.; Guo, A. Association between point-of-care CRP testing and antibiotic prescribing in respiratory tract infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis of primary care studies. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e787–e794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Goyder, C.R.; Ananthakumar, T.; Tan, P.S.; Turner, P.J.; Hayward, G.; Van den Bruel, A. The clinical utility of point-of-care tests for influenza in ambulatory care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, J.; Butler, C.; Hopstaken, R.; Dryden, M.S.; McNulty, C.; Hurding, S.; Moore, M.; Livermore, D.M. Narrative review of primary care point-of-care testing (POCT) and antibacterial use in respiratory tract infection (RTI). BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2015, 2, e000086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepser, D.G.; Klepser, M.E.; Dering-Anderson, A.M.; Morse, J.A.; Smith, J.K.; Klepser, S.A. Community pharmacist–physician collaborative streptococcal pharyngitis management program. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2016, 56, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arieti, F.; Göpel, S.; Sibani, M.; Carrara, E.; Pezzani, M.D.; Murri, R.; Mutters, N.T.; Lopez-Cerero, L.; Voss, A.; Cauda, R.; et al. White Paper: Bridging the gap between surveillance data and antimicrobial stewardship in the outpatient sector—practical guidance from the JPIAMR ARCH and COMBACTE-MAGNET EPI-Net networks. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 2020, 75, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, G.V.; Fleming-Dutra, K.E.; Roberts, R.M.; Hicks, L.A. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016, 65, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, D.; Civil, M.; Donnison, A.; Hogden, A.; Hinchcliff, R.; Westbrook, J.; Braithwaite, J. A mechanism for revising accreditation standards: A study of the process, resources required and evaluation outcomes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debono, D.; Greenfield, D.; Testa, L.; Mumford, V.; Hogden, A.; Pawsey, M.; Westbrook, J.; Braithwaite, J. Understanding stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences of general practice accreditation. Health Policy 2017, 121, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. National Competency Standards Framework for Pharmacists in Australia 2010. Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. 2010. Available online: https://www.psa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/National-Competency-Standards-Framework-for-Pharmacists-in-Australia-2016-PDF-2mb.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathivadi, P.; Buckingham, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Hawes, L.; Saha, S.K.; Barton, C.; Mazza, D.; Russell, G.; Sturgiss, E. Implementation science: An introduction for primary care. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charani, E.; Smith, I.; Skodvin, B.; Perozziello, A.; Lucet, J.C.; Lescure, F.X.; Birgand, G.; Poda, A.; Ahmad, R.; Singh, S.; et al. Investigating the cultural and contextual determinants of antimicrobial stewardship programmes across low-, middle-and high-income countries—A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209847. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer, E.G. Enlarging the conceptualization of mixed method approaches to grounded theory with intervention research. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkens, J.J.; Van Agtmael, M.A.; Peters, E.J.; Lettinga, K.D.; Van Der Kuip, M.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.; Wagner, C.; Kramer, M.H. Behavioral approach to appropriate antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals: The Dutch Unique Method for Antimicrobial Stewardship (DUMAS) participatory intervention study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.K.; Kong, D.C.M.; Thursky, K.; Mazza, D. Development of an antimicrobial stewardship implementation model involving collaboration between general practitioners and pharmacists: GPPAS study in Australian primary care. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2021, 22, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Carayon, P.; Gurses, A.P.; Hoonakker, P.; Hundt, A.S.; Ozok, A.A.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J. SEIPS 2.0: A human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.C.; Tamma, P.D.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Miller, M.A.; Sateia, H.; Szymczak, J.; Gurses, A.P.; Linder, J.A. Ambulatory antibiotic stewardship through a human factors engineering approach: A systematic review. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 2018, 31, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurses, A.P.; Ozok, A.A.; Pronovost, P.J. Time to accelerate integration of human factors and ergonomics in patient safety. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asan, O. Providers’ perceived facilitators and barriers to EHR screen sharing in outpatient settings. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stiphout, F.; Zwart-van Rijkom, J.E.F.; Maggio, L.A.; Aarts, J.E.C.M.; Bates, D.W.; van Gelder, T.; Jansen, P.A.F.; Schraagen, J.M.C.; Egberts, A.C.G.; ter Braak, E.W.M.T. Task analysis of information technology-mediated medication management in outpatient care. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 80, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.K.; Snowdon, C.; Francis, D.; Elbourne, D.R.; McDonald, A.M.; Knight, R.C.; Entwistle, V.; Garcia, J.; Roberts, I.; Grant, A.M.; et al. Recruitment to randomised trials: Strategies for trial enrolment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol. Assess. 2007, 11, 105. Available online: http://www.ncchta.org/fullmono/mon1148.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.; Hunter, A. Multimethod Research: A Synthesis of Styles. Sage Publications, Inc.. 1989. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/nur.4770140212 (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Duncan, E.; O’Cathain, A.; Rousseau, N.; Croot, L.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; Yardley, L.; Hoddinott, P. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): An evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Studies That Contributed Evidence for the GPPAS Model | Methods | No. of Studies/Participants (Settings) | Aim | Key Outcomes | Key Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1: Effectiveness of Interventions Involving Pharmacists on Antibiotic Prescribing by General Practitioners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [13] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 35 Studies General practice | To identify which interventions involving pharmacists could improve antibiotic prescribing by GPs | A meta-analysis of 15 studies found a reduction in the antibiotic prescribing rate (odds ratio 0.86 and 95% CI 0.78–0.95) and an improved guidline-adherent antibiotic prescribing rate (odds ratio 1.96 and 95% CI 1.56–2.45) when interventions were implemented by a GP/pharmacist team. A list of effective GPPAS strategies included: (1) GP/pharmacist group meetings, (2) academic detailing by a GP/pharmacist team, (3) the development of GP–CP collaboration development and use of local antibiotic guidelines, (4) auditing antibiotic prescriptions and providing feedback to GPs, (5) implementing a delayed prescribing strategy by a GP/pharmacist partnership, (6) workshop training involving GPs and pharmacists, (7) use of point-of-care tests in a GP/pharmacist practice agreement model, (8) reviewing of antimicrobial prescriptions by pharmacists and communication with GPs, and (9) use of common patient educational leaflets and antibiotic checklists. | GPPAS interventions were effective to reduce antibiotic prescribing and improve guideline-adherent antibiotic prescribing by GPs. However, context specific evidence is required to understand their usage in routine practice and implementation barriers. |

| Study 2: Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Community Pharmacists towards Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Systematic Scoping Review of Survey Studies [21] | Scoping review | 10 Studies Community pharmacy | To review AMS survey studies and to determine the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of community pharmacists regarding AMS | This review identified a small (10 surveys globally) but growing body of survey studies in the literature that concerned CP-AMS. The dearth of surveys (only three were validated surveys) indicated suboptimal progress of AMS implementation in community pharmacies and a need for future studies to comprehensively understand the AMS situation in Australian community pharmacies. CPs believed that AMS improved patient care and reduced inappropriate antibiotic use. CPs had limited communications with prescribers about infection control and the uncertainty of antibiotic treatment. Nearly half of the surveyed CPs educated patients. The most commonly reported barriers to AMS implementation involved a lack of training, practice guidelines, access to prescribers, and reimbursement models. | There is a limited number of good quality validated AMS survey instruments around the world to assess CPs’ knowledge, use of evidence-based AMS strategies, collaboration with prescribers to identify stewardship targets, and to monitor stewardship progress in community pharmacies. The mechanism on how to improve engagement of CPs in AMS needs more research in the future. |

| Study 3: A Nationwide Survey of Australian General Practitioners on Antimicrobial Stewardship: Awareness, Uptake, Collaboration with Pharmacists and Improvement Strategies [22] | Nationwide survey | 386 GPs General practice | To assess GPs’ awareness of AMS, uptake of AMS strategies, attitudes towards GP-pharmacist collaboration in AMS, and perceived challenges of doing AMS activities in routine practices | Most GPs were familiar with AMS. Two strategies were found to had increased uptake: the use of therapeutic guidelines “Antibiotics” (83%) and delayed prescribing (72.2%). Point-of-care testing (18.4%), patient information leaflets (20.2%), peer-prescribing reports (15.5%), and audits with feedback programmes (9.8%) were rarely used. Among the GPs, 50% were receptive to recommendations by pharmacists on the choice of antimicrobial and 63% were receptive to recommendatins by pharmacists on the dose. A policy fostering increased GP-pharmacist collaboration in AMS was supported by more than 60% of the surveyed GPs. Patients’ quick recovery desires broad recommendations in the antibiotic guideline, limited access to ID physicians andpharmacists, and prompt microbiological services, decision support tools, and the lack of education and training on AMS programmes were common reported barriers to optimal antibiotic prescribing. | GPs were aware of AMS but the implementation of evidence-based AMS strategies was inadequate. The majority of GPs were receptive to a pharmacist’s interventions to optimise antimicrobial use. The development of a feasible GP/pharmacist collaborative AMS implementation model, supplying stewardship resources and facilitating training could improve GPs’ participation to foster AMS activities in primary care. |

| Study 4: Antimicrobial Stewardship by Australian Community Pharmacists: Uptake, Collaboration, Challenges, and Needs [23] | Nationwide survey | 613 Community pharmacists (CPs) Community Pharmacy | To assess CPs’ awareness, uptake of evidence-based AMS strategies, attitudes toward collaboration with GPs in AMS, and barriers to improving AMS practices in pharmacies | Although CPs were familiar, they felt there was a need for training (76.5%) and access to AMS practice guidelines (93.6%). CPs often counseled patients and reviewed drug interactions (93.8%) but less frequently used the national Therapeutic Guideline (Antibiotic) (45.5%) and assessed the guideline compliance of prescribed antimicrobials (37.9%). CPs inadequately communicated with GPs (41.8%) regarding suboptimal antimicrobial prescription. CPs believed that GPs were non-receptive to their recommendations. CPs strongly believed that GPs should accept their recommendations on choice (82.6%) and dosage (68.6%). CPs uncommonly used the point-of-care tests (19.1%) and patient information leaflets (24.5%). Most surveyed CPs strongly supported policies regarding GP-pharmacist collaboration (92.4%), limiting accessibility of specific antimicrobials (74.4%), and reducing repeat dispensing of antimicrobial (74.2%). CPs identified interpersonal, interactional, structural, and resource-level barriers to spontaneously participate in AMS activities. | CPs are aware of the judicious use of antimicrobials but they need training and resources to routinely practice AMS. The receptiveness of GPs and a GP–CP collaboration system structure may accelerate CPs’ engagement in AMS. |

| Study 5: Divergent and Convergent Attitudes and Views of General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists to Collaboratively Implement Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Australia: A Nationwide Study [24] | Nationwide survey | 999 Participants Quantitative responses: 386 GPs and 613 CPs Qualitative responses: 221 GPs and 592 CPs General practice and community pharmacy | To unveil GPs’ and CPs’ convergent and divergent attitudes regarding implementation of AMS and to understand challenges of collaboration in AMS issues between GPs and CPs | The need for AMS training by CPs was significantly higher than GPs (p < 0.0001). GPs used Therapeutic Guideline (Antibiotic) at much higher rate than CPs (p < 0.0001). No interprofessional difference was found in using patient information leaflets and point-of-care tests. CPs were highly likely to collaborate with GPs (p < 0.0001) but both professionals believed that policies that support GP–CP collaboration are needed to implement GPPAS intervention strategies. The collaboration challenges in implementing AMS were found at the level of persons, logistics, organisations, and policies. | There are opportunities for GP–CP collaboration in AMS, however, health system structures supporting routine collaboration and collaborative practice agreements between GP and pharmacy practices are key to foster GP/CP interprofessional trust for implementing AMS, developing AMS competencies together, and promomting communications for AMS activities. |

| Study 6: Systems Thinking Approach to Improve Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care [25] | Rapid review | General practice and community pharmacy context | To analyse system thinking approaches how to improve implementation of AMS programmes in primary care involving interprofessional collaboration and communication | Systems thinking could help scrutinise the priority thoughts before, during, and after designing and implementing AMS programmes in primary care. Important areas involve how to incorporate AMS resources into an existing health system and by whom, understanding system structures and external factors that may operationalise AMS programmes, building interdependent AMS teams, and predicting a change in antimicrobial use over time. Opportunities are surmounting regarding how to transform antimicrobial-use behaviours culturally and structurally through establishing a sustainable AMS friendly health service model that ensures patient-centred but interprofessional antimicrobial care in primary care in the future. | Systems thinking approaches are important to determine the required arrangements for AMS resources, their access to health professionals, organisational system structures that would support routine AMS activities, dynamic system behaviours, and interprofessional communication and collaboration for practical design and implementation of AMS programmes in primary care. |

| Study 7: The Effectiveness of a Simple Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention in General Practice in Australia: A Pilot Study [26] | Pilot implementation study in Australian primary care | A general practice in Victoria, Australia | To evaluate the impact of a novel GP educational intervention involving pharmacists improving appropriateness and guideline compliance of antimicrobial prescriptions | A GP educational AMS programme was significantly effective in improving appropriateness in antimicrobial selection (73.9% vs. 92.8%, RR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.18–1.34), duration (53.1% vs. 87.7%, RR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.49–1.83) and guideline compliance (42.2% vs. 58.5%, RR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.19–1.61). | The implementation of a GP educational programme involving pharmacist is effective to significantly improve appropriateness and guideline compliance of GPs’ antimicrobial prescriptions. The findings indicate that GP/pharmacist AMS education has an important role and should be sustainably continued for antimicrobial education within general practice. |

| Key Problems | Facilitator | Opportunities | SEIPS 2.0 Components | Proposed Quality Improvement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited education, training, and professional development regarding AMS practice, strategies, and goals | The implementation of AMS training courses as part of the professional development modules of GPs and CPs are essential for their competency in AMS and participation in collaborative AMS activities. Incorporation of these courses into the GP/pharmacy curriculum of undergraduate and graduate programme would be valuable. | GPs (46.4% of 386) and CPs (76.5% of 613) felt that they would need AMS education and training [22,23]. Most GPs (72% of 386) and CPs (87.3% of 606) strongly agreed to receive AMS training in the future [24]. Their willingness is an opportunity to facilitate AMS training programme in general practices and community pharmacies in Australia | Person | GPPAS implementation model for AMS educational programmes |

| Potentially limited resources for routine use to make a shared decision about antimicrobial use during consultation and counselling with a patient | Antibiotic checklist, AWaRe tools, and patient-facing information leaflets | Less than 25% of surveyed GPs and CPs used patient information leaflets [22,23] and both professionals reported that these information sheets were not readily available for routine use [24]. They believed that these resources would help improve patient awareness and patient pressure on antibiotic use. | Physical environment Tools and Technology | Access to AMS resources |

| Patient expectation to receive an antimicrobial prescription while visiting a GP/CP with a symptom non-suggestive of antimicrobial use | Patient education and antimicrobial awareness campaigns, provide a patient with a take-home message about how to self-care and seek further advice in treating self-limiting infections | Most GPs (76.8% of 383) and CPs (82.4% of 608) educated patients about unintended consequences of antimicrobial use (e.g., AMR and gut effect) but without using any formal tools [22,23]. GP/pharmacy practice-based supply of these resources could be an opportunity to disseminate antibiotic awareness common messages at a community level through GP/pharmacist joint venture projects. | Person Task | GP-patient communication |

| CP-patient communication | ||||

| Lack of GP/CP communication regarding an antimicrobial prescription including a delayed antimicrobial prescription | Receptiveness of GPs to accept CPs’ recommendations Information technology support, telehealth-led antimicrobial reviews, case conferencing to discuss antimicrobial review outcomes GP-pharmacist partnerships to avoid early dispensing of delayed prescribed antimicrobial(s) | GPs felt that they should be receptive to CPs’ recommendations on the choice (50.5% of 381) and dose (63% of 382) of antimicrobials [22]. GPs’ willingness to accept that pharmacists’ recommendations where appropriate can be considered as pivotal for GP–CP collaboration with antimicrobial prescriptions. | Person Organisation Tools and technology Policy | GPPAS implementation model for delayed antimicrobial prescriptions |

| GPPAS implementation model for routine review of antimicrobial prescriptions | ||||

| No local or national GP/pharmacy practice agreements and policies supporting collaboration in AMS | GP/CP practice agreements and relevant policies | Most CPs (94% of 606) and the majority of GPs (60.9% of 381) believed that a policy supporting their collaboration in AMS was needed to improve AMS in the community [24]. Future policy initiatives surrounding the establishment of GP/pharmacy practice agreements could support implementation of GP/pharmacist collaborative AMS strategies at the local level in the short term and the national level in the long run. | Organisation External environment | Policy environment |

| Poor tracking and monitoring system to identify inappropriate prescribing and provide feedback | Validated tools supporting antimicrobial audits GP/pharmacist local AMS team. | GP-pharmacist collaborative antimicrobial audit models were interprofessionally (46.1% of GPs and 86.5% of CPs) supported to optimise antimicrobial therapy [24]. CPs’ optimistic desire to be involved in antimicrobial audit programmes can facilitate implementation of an audit feedback strategy in primary care. | Organisation | GPPAS implementation model for antimicrobial audits and feedback programmes |

| CPs’ lack of access to clinical indications and diagnostic reports to review antimicrobial prescriptions | User friendly “MY Health Records”, GPs’ mandatory reporting of clinical indication for an antimicrobial prescription | Most CPs believed that having access to a patient’s clinical and diagnostic information would assist reviewing the guideline adherence of prescribed antimicrobial(s). | Physical environment | GPPAS implementation model for antimicrobial reviews |

| Organisational system structure | ||||

| Lack of technology support to make optimal decisions about antimicrobials in a busy practice environment | CDSS, eTG (Antibiotic) integrated with prescribing and dispensing software | Nearly 30% of surveyed GPs and CPs [22,23] felt that, if AMS resources were linked with prescribing and dispensing software, considering AMS in a busy environment would be easier. | Tools and technology | Access to resources |

| Diagnostic uncertainty about the cause of infections | Availability and accessibility of point-of-care tests in GP and pharmacy facilities. Policy supporting the use of point-of-care diagnostic tests to determine the cause of patient infections, either bacterial or viral. | Less than 20% of surveyed GPs (N = 386) and CPs (N = 613) used point-of-care tests [24] but both professionals were supportive to introduce evidence-based point-of-care testing facilities to improve their diagnosis and antibiotic treatment decisions for patients seeking treatment for common and acute infections. | Tools and technology External environment | GP/pharmacist diagnostic stewardship model |

| Policy environment |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saha, S.K.; Thursky, K.; Kong, D.C.M.; Mazza, D. A Novel GPPAS Model: Guiding the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care Utilising Collaboration between General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091158

Saha SK, Thursky K, Kong DCM, Mazza D. A Novel GPPAS Model: Guiding the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care Utilising Collaboration between General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists. Antibiotics. 2022; 11(9):1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091158

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaha, Sajal K., Karin Thursky, David C. M. Kong, and Danielle Mazza. 2022. "A Novel GPPAS Model: Guiding the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care Utilising Collaboration between General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists" Antibiotics 11, no. 9: 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091158

APA StyleSaha, S. K., Thursky, K., Kong, D. C. M., & Mazza, D. (2022). A Novel GPPAS Model: Guiding the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care Utilising Collaboration between General Practitioners and Community Pharmacists. Antibiotics, 11(9), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11091158