Abstract

With the objective of evaluating the quality parameters of raw milk in Ecuador between 2010 and 2020, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 73 studies on raw milk produced in different regions of Ecuador was performed. Under the random effects model, effect size and heterogeneity were determined vs. climatic region both among analyses and studies, with Cochran’s Q, I2 and Tau (π) statistics. For all the variables, it was observed that there was great heterogeneity (I2 > 90%) among the studies; additionally, it was found that climatic region had an influence only among the variables arsenic, mercury, pH and total solids, and it was greater in the coastal region than the Inter-Andean region. The mean values of the physicochemical characteristics of the milk (titratable acidity, ash, cryoscopy, fat, lactose, pH, protein, non-fat solids and total solids) in the great majority of these studies were within the range allowed by Ecuadorian regulations. As for the hygienic quality of raw milk (total bacterial count, somatic cell count and presence of reductase), although the mean values were within those determined by local legislation, it should be noted that the range established by Ecuadorian regulations is relatively much higher compared to other regulations, which possibly means that there is a high presence of bacteria and somatic cells in raw milk. Finally, the presence of several adulterants (added water) and contaminants (AFM1, antibiotics and heavy metals) was confirmed in the milk, in addition to other substances such as eprinomectin, zearalenone and ptaquilosides, whose presence can be very dangerous, because they can be hepatotoxic, immunotoxic and even carcinogenic. In conclusion, there is great variability among the studies reviewed, with the physicochemical characteristics being the most compliant with Ecuadorian legislation; the hygienic characteristics, adulterants and contaminants of raw milk require greater attention by producers and local authorities, so that they do not harm the health of consumers and the profitability of producers in Ecuador.

1. Introduction

Systematic reviews are a set of studies that aim to answer a research question, in which an exhaustive search of the available information (studies that answer the research question) and synthesis of the results found in such research are performed; such a procedure requires a critical, reproducible and transparent methodology [1]. Meta-analysis is a statistical tool that integrates, synthesizes and quantifies the results that have been published on a variable of interest, based on predefined, clear and reproducible criteria, which allows a reduction of the biases that are commonly present in other types of reviews. In addition, it allows researchers to obtain a measure of the effect that certain specific factors may have on the response variable in a more accurate way compared to individual studies [2].

Milk is essential for people’s nutrition due to its great contribution of nutrients and biofunctional molecules, so carrying out controls and studies that guarantee its safety is of utmost importance for public health [3]. In Ecuador, the dairy industry is one of the most important economic activities involving livestock [4], where greater emphasis has been given to the production of milk of optimal quality, from a compositional point of view, because the price of milk for the producer is based on these characteristics [5,6,7]. In 2021, Ecuadorian milk production was 5.70 million liters per day, which was 7.31% lower than in 2020. The largest milk-producing province is Pichincha, followed by Azuay, and then, Manabí, where 74.85% of the total production is sold in liquid form, 16.39% is processed on the land, 6.76% is used for calf consumption, 1.87% is used for feeding from the bucket and 0.13% is milk wasted on land [8]. The rate of fluid-milk consumption is approximately 110 L per inhabitant each year [9]. The necessity for constant improvement in Ecuador’s dairy sector and globalization demand greater efforts in order to achieve efficient productivity and competitiveness; this makes the formulation and implementation of evaluation and control strategies indispensable for the diagnosis of situations [10,11]. In Ecuador there are several independent studies that are diverse and that have not been systematically analyzed within a period of time, so the integration of information on the topic of interest has not been performed. Therefore, the general objective of the present research was to analyze the physicochemical characteristics (fat, protein, lactose, total solids, non-fat solids and ash) and hygienic characteristics (bacteria, somatic cells and reductase), as well as the presence of contaminants (antibiotics, mycotoxins, heavy metals, preservatives and neutralizers) and adulterants (added water, starches and chlorides) in raw milk produced in Ecuador, through a systematic literature review and meta-analysis, in studies conducted between 2010 and 2020.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

We searched for studies that were published in certain repositories and indexed, and undergraduate and graduate degree works, between January 2010 and December 2020, that were carried out in Ecuador. A search of various studies in university repositories and indexed journals was carried out, in conjunction with review by three researchers, from several electronic databases (Google Scholar, Pubmed, Elsevier, Dialnet and Science Direct (Journal)) and in the repositories of the Universities of Ecuador, of undergraduate and graduate research topics. A combination of keywords was used for the search (milk, raw, hygiene, bacteria, somatic cells, quality, Ecuador and cows, among others) both in Spanish and English.

The response variables were the hygienic characteristics of the milk (bacteria, somatic cells and pathogens), as well as the presence of contaminants (antibiotics, mycotoxins, heavy metals, preservatives and neutralizers) and adulterants (added water, starches, chlorides and vegetable fats). The moderating variable to consider was the region of Ecuador where the study was conducted.

2.2. Literature Inclusion Criteria and Data Extraction

We used those studies (scientific articles, undergraduate or graduate theses and publications) in which it was possible to detect and measure one or more parameters in raw milk, in terms of hygienic characteristics, composition, physicochemical properties, contaminants and adulterants; likewise, it was necessary that at least 10 observational units were available, with the mean, minimum and maximum values obtained. Publications where the methodology, results or conclusions were not clear; that were irrelevant (without important information); that were without statistical or quantitative contribution; that were without complete data; that duplicate studies; or that were conducted prior or subsequent to the study period were not taken into account.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained for the variables of interest were tabulated in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. For statistical processing of the data, the Metafor MAd package of the free statistical software RStudio, version 1.2.5019 (RStudio Inc. Boston, MA, USA) was used. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. The data were analyzed using weighted random-effects meta-analysis models for the differences among the study means and the relationships of the studies with climate region. Statistical heterogeneity was analyzed using Cochran’s Q statistic, Higgins’ inconsistency (heterogeneity index I2), and the Tau-squared (π2) statistic. This research was not based on the recommendations indicated by PRISMA, as these are observational and multivariate studies.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Process of Study Selection and Searched Results

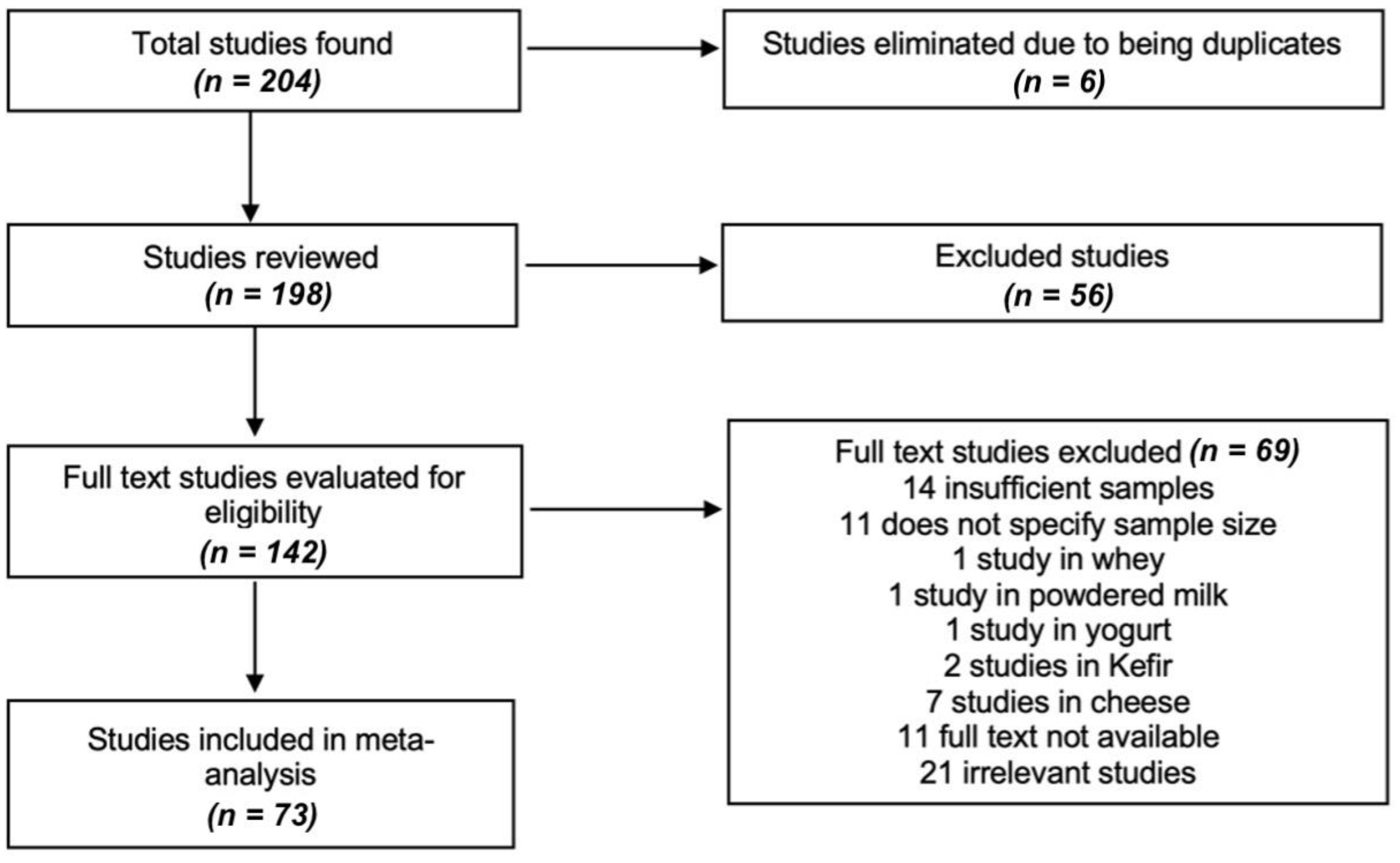

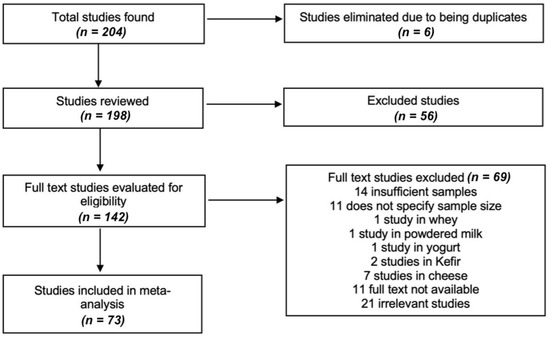

The process of choosing and discarding studies is detailed in Figure 1. Based on our criteria, the studies should include information on the sample size, the author, the year, the province of study and the ranges of values. Subsequently, the data for the meta-analysis were selected from the text, appendices, tables or graphs of each selected study and recorded in a personalized way for the systematic review. Data were extracted on the authors, the year of publication, the year of study, the complete title, the type of study, the location (coast, Inter-Andean or Oriental region), the number of samples, the results of the analysis of each variable, the statistics and the availability link of the selected documents.

Figure 1.

Flow chart summarizing the process of study selection. We identified 204 studies from which 198 unique references were retrieved, where we evaluated the full text of 142 studies, of which 69 studies were excluded and only 73 studies [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] were meta-analyzed (view: Supplementary Materials); no additional studies were identified after updating the literature search.

3.2. Overall Results of the Literature

Table 1 shows the values of each variable analyzed and found in the systematic review, with respect to the studies found and the climatic regions, based on the limits allowed by the Ecuadorian Technical Standard (NTE) INEN 9 [84], which establishes the requirements that raw milk should meet in Ecuador; it also shows the mean, minimum and maximum values of these parameters, the number of studies analyzed, the total number of samples, the percentage of samples outside the allowed range and the percentage of non-compliance.

Table 1.

Allowable limits, measures of central tendency, studies analyzed and % compliance of the variables used in the study.

As indicated by the analyzed studies, there is high non-compliance of the raw milk analyzed between 2010 and 2020 with respect to Ecuadorian regulations, especially regarding hygienic quality, contaminants and adulterants; this constitutes a serious public health problem. For example, in the case of heavy metals, the single study that aimed to determine lead in milk in Ecuador found that 98.28% (57/58) of the samples analyzed contained levels above the maximum level permitted by Ecuadorian regulations. Similarly, according to the analysis of mercury and arsenic, it was found that 25.64% samples (20/78) exceeded the limits allowed in food. Likewise, 89.06% (114/128) of the samples analyzed exceeded the permitted limits for the variable “Ptaquiloside”, which is a toxin of the fern Pteridium aquilinum that can be present in milk when the cow ingests this weed. In the case of the presence of antibiotics, it was determined that 14.55% (370/2543) of the milk samples contained them.

Regarding adulteration, the presence of water addition was found in 61.46% (118/192) of samples in three different studies, while 27.76% (457/1646) of the samples had altered values of the freezing point of milk (cryoscopy) in eight different studies. In the single study on the determination of glycomacropeptide (GMP), an indicator of milk adulteration with cheese whey, it was found to be present in 37.50% (9/24) of the samples investigated.

Regarding hygienic quality, 20.38% (22,338/109,610) of the samples had total bacterial counts higher than the maximum allowed by NTE INEN 9 (1 × 106 CFU/mL); if this parameter was analyzed using international standards, the percentage of non-compliance would be alarmingly higher. This is related to indirect tests for determining bacterial contamination in milk; for example, for the reductase test, 61.80% (596/932) of the samples did not comply with Ecuadorian regulations; likewise, the parameters of pH and titratable acidity showed non-compliance of 36.06% (331/918) and 12.72% (201/1580), respectively. Among the 30 studies analyzed on somatic cell count, it was determined that 0.80% (878/110,347) presented values above the maximum allowed by NTE INEN 9, which establishes a maximum limit of 700,000 (CS/mL). However, it should be clarified that the Ecuadorian upper limit is considerably higher than the international standard (up to 400,000 CS/mL).

Regarding the presence of chemical products that are intended to mask the acidity of milk, non-compliance of 14.21% (137/951) and 6.03% (61/1011) was found for the presence of neutralizing substances and peroxides, respectively. Likewise, relative density and protein stability tests showed non-compliance of 11.30% (224/1983) and 11.70% (171/1462), respectively. Regarding AFM1—belonging to the group of aflatoxins (AF), which are extremely toxic substances from the fungus Aspergillus, which contaminates plant foods—when ingested by dairy cows, they are converted in the liver from AFB1 to AFM1, which is eliminated through milk [85]; AFM1 is a mycotoxin classified as potentially carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer—IARC [86]. In our review, only 1% (4/401) of the samples analyzed exceeded the maximum permitted limit of AFM1 allowed by NTE INEN 9. For the parameters of chlorides, colorants, starches, the drug eprinomectin and the mycotoxin zearalenone, no non-compliance was found with respect to Ecuadorian regulations.

In the case of the chemical characteristics of the milk, the parameter of non-fat solids (NFS) presented non-compliance of 12.64% (247/1954), ashes in 7.89% (34/431), lactose in 5.10% (56/1097), protein in 0.93% (1012/109 020), fat in 0.52% (564/109 428) and total solids in 0.48% (511/106 707) of the analyzed samples; therefore, the great majority of the parameters did comply with the local legislation.

3.3. Meta-Analysis of Variables by Sample and by Region

Table 2 shows the statistical analysis of the meta-analysis of the parameters of raw bovine milk analyzed between 2010 and 2020 in Ecuador. There were parameters that could not be meta-analyzed, either because their values were zero (0), as in the case of starch and chloride variables, or because there was only one study of that parameter, as in the case of colorants, eprinomectin, glycomacropeptide, lead and zearalenone. For the rest of the parameters, it was observed that the heterogeneity index (I2), in all cases was higher than 90%, which indicates very high variability among the studies and is well above the acceptable limit (40–50%) in meta-analysis. This variability is confirmed by observing the coefficient of the H2 statistic, which is quite variable.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of variables, by sample and by region.

The results shown in Table 2 suggest that the studies included in this research work should not have been meta-analyzed since they are very different from each other; however, we proceeded to perform the statistical analysis, since they are observational studies and we wish to compare these results with respect to compliance (or a lack of it) with NTE INEN 9. In the case of the statistical analysis by study, we observed that the result of the p-value of Q, in all cases, was less than 0.05, which confirms the existence of significant differences among them. Regarding the statistical analysis between regions (Inter-Andean vs. coast), for the variables of added water, lactose, neutralizers and ptaquilosides, we have no comparison, since the studies were only carried out in the Inter-Andean region. Regarding the variables of arsenic, mercury, pH and total solids, a p-value of Q < 0.05 was observed, indicating a higher presence in the coastal region. The rest of the variables presented a p-value of Q > 0.05, so no significant differences were found between the regions.

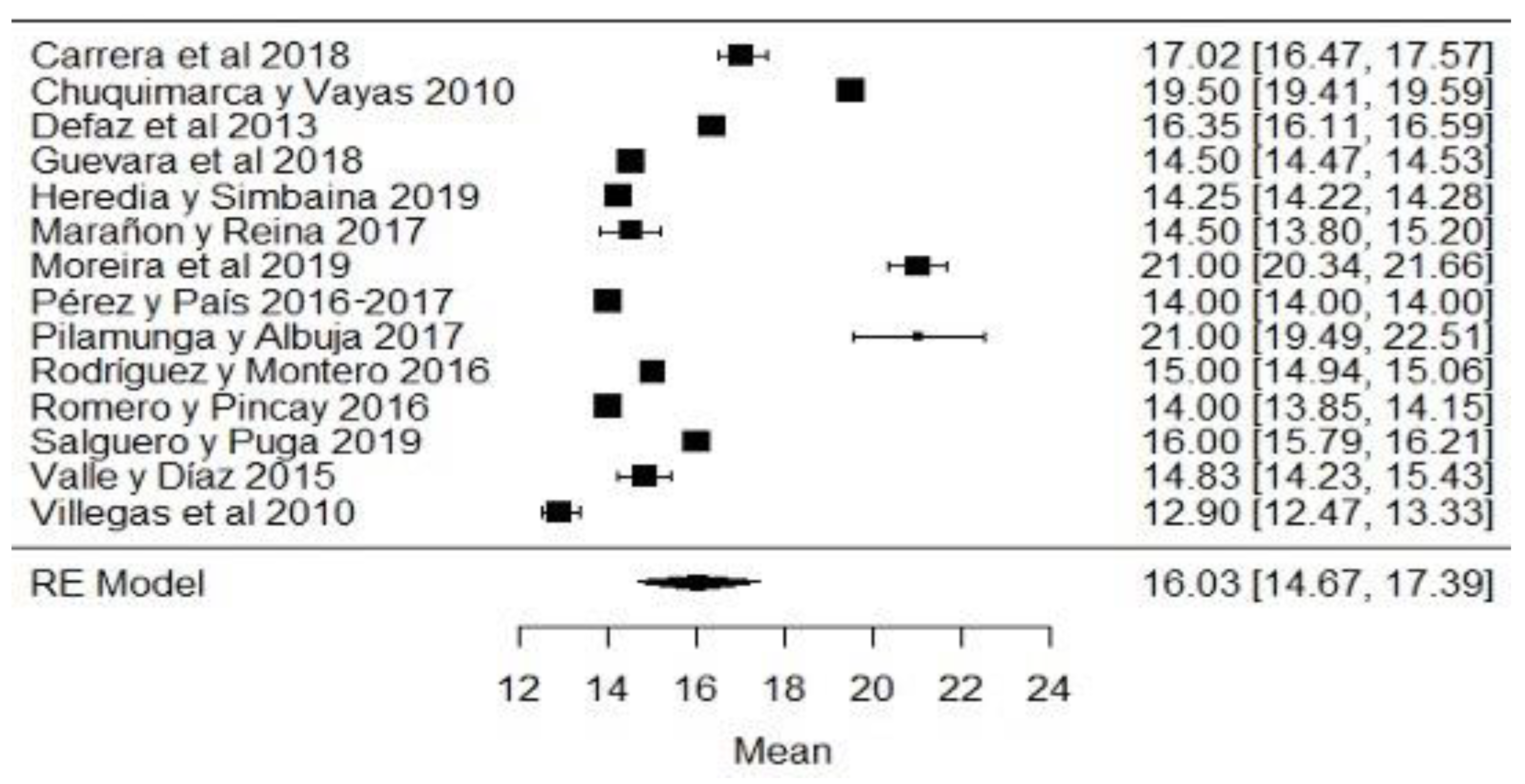

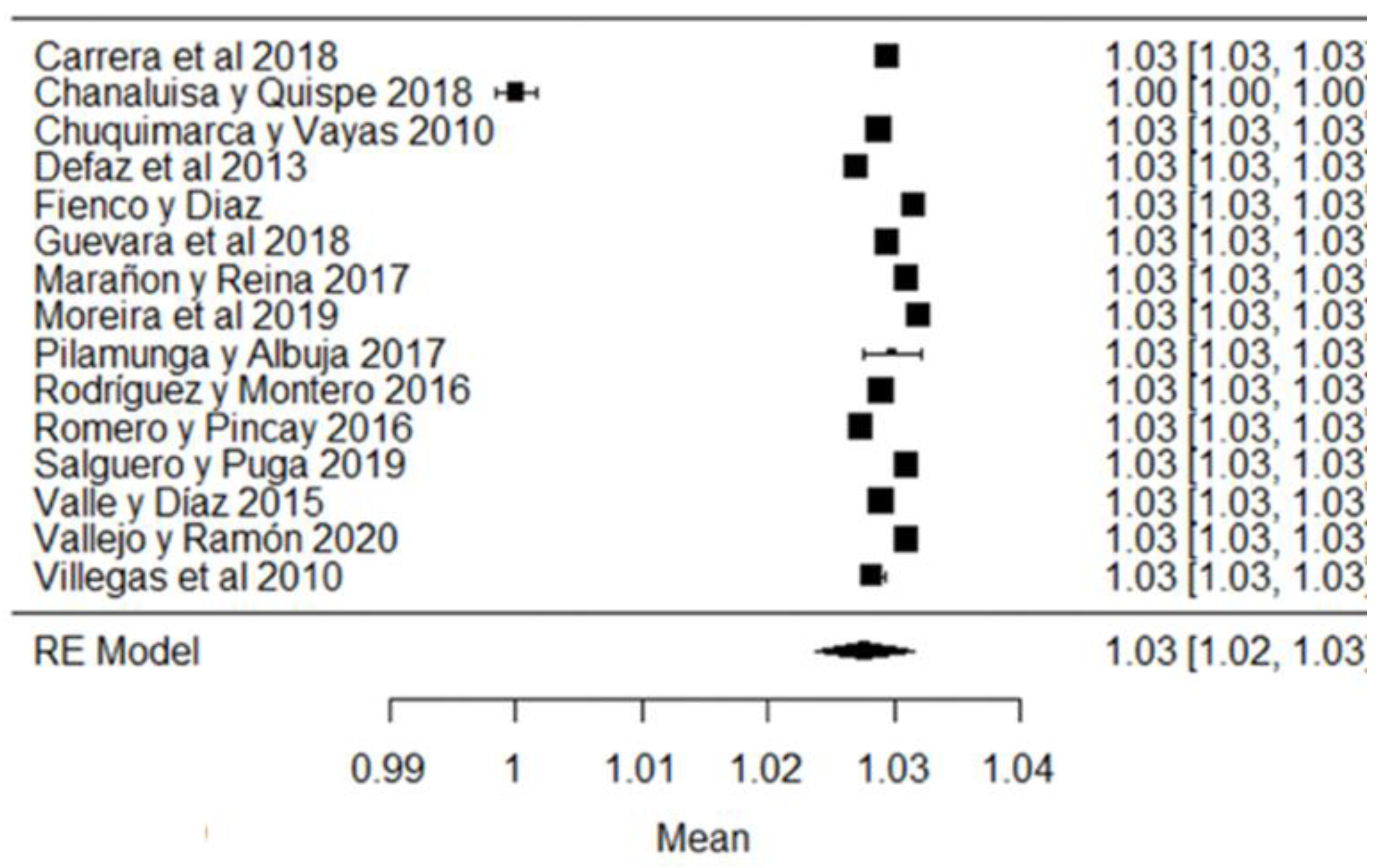

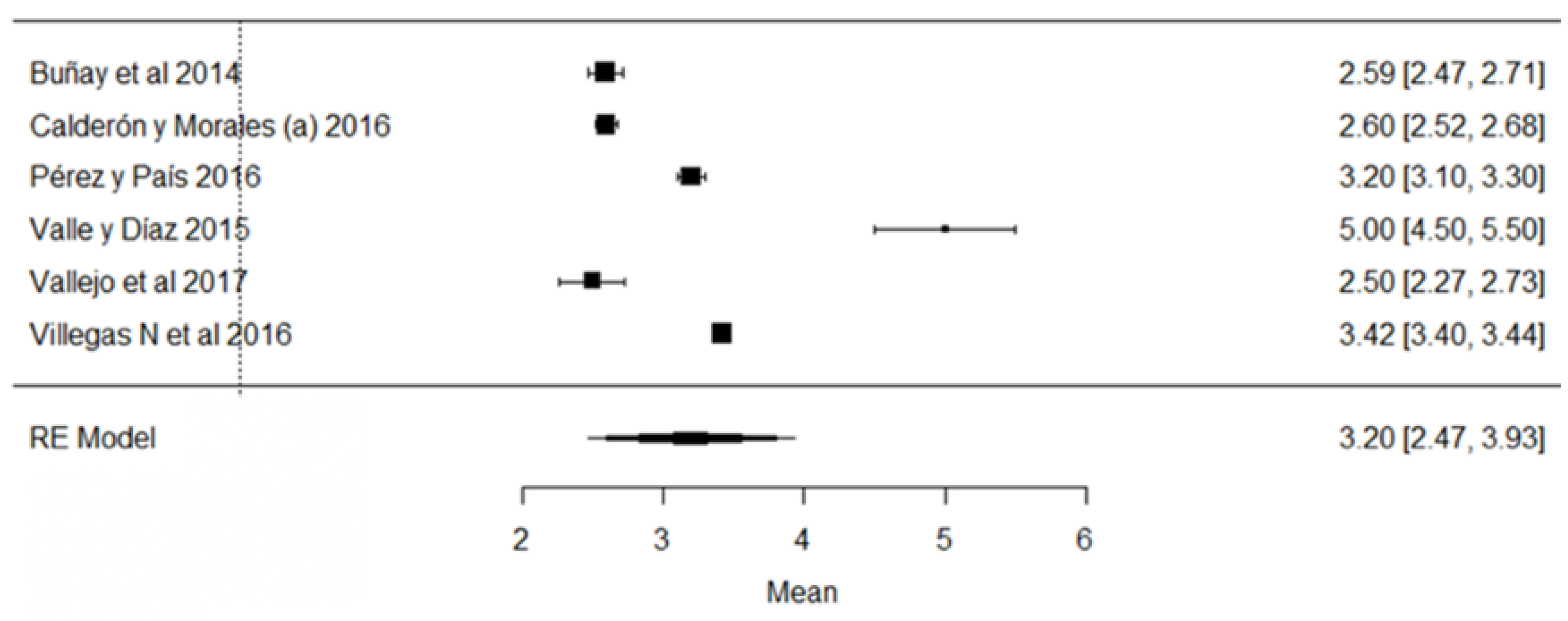

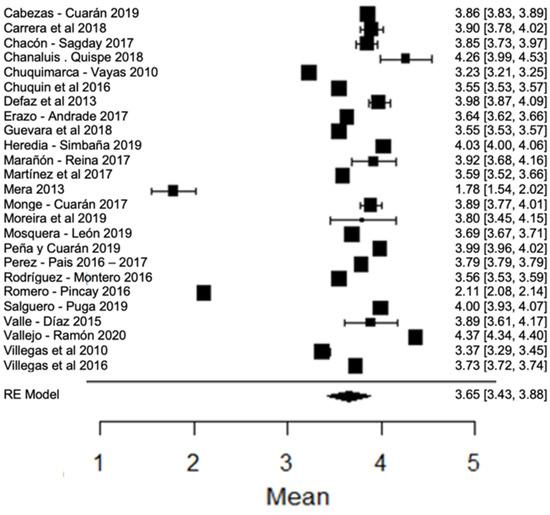

3.4. Forest Plot of the Physicochemical Variables of Milk by Sampling and by Region

When analyzing the forest plots of titratable acidity, ash, cryoscopy, fat, lactose, pH, protein, non-fat solids and total solids, it can be observed that the average effect size, represented by a rhombus, along with most of the studies and their averages, is within the range allowed by NTE INEN 9. For example, in the case of titratable acidity (Figure 2), some studies [18,36,60] present values above what is stipulated, while the study of [38] is below what is allowed. The titratable acidity is elevated when microbiological contamination occurs, while if it is decreased, it may be due to the presence of mastitis, adulteration with water or alteration by an alkalinizing [87].

Figure 2.

Forest plot of titratable acidity by study [16,18,21,23,24,26,35,36,38,39,44,60,61,79].

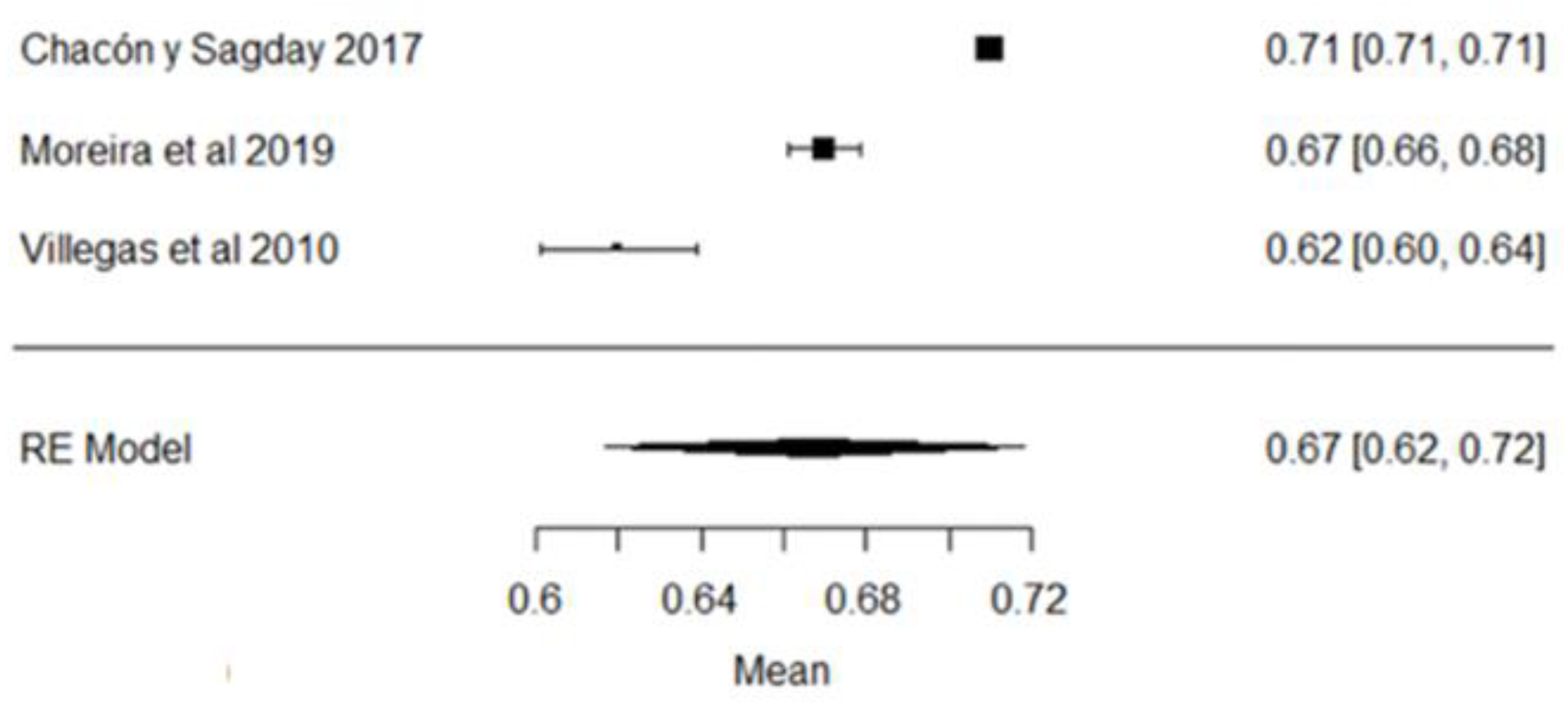

In the case of ashes, the study whose mean is below what is required (Figure 3) is that of [38]. All the studies show large variability with respect to the global mean, which is evident in the forest plot (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ash forest plot [18,38,42].

In the case of cryoscopy, the studies of [38,42,44,79] report values, on average, outside the requirements of the Ecuadorian standard (Figure 4), with the last study mentioned being the one that shows the greatest variability with respect to the mean (Figure 4). Values approaching the freezing point of 0 °C indicate the addition of water, heating, the precipitation of phosphates in the raw milk, etc. [87].

Figure 4.

Cryoscopy forest plot [14,33,38,42,44,53,69,79].

Regarding the relative density parameter, the research of [51] presents values much lower than the minimum allowed. Regarding the forest plot (Figure 5) of the climatic period, although most of the studies comply with the Ecuadorian standard, the results found by [18,24] present greater variance with respect to the global mean. Lower values indicate adulteration with water, while higher values may indicate skimming of the milk or the use of adulterating substances such as starch or salt, since these are used to balance the density of the milk after adding water [88,89].

Figure 5.

Forest plot of relative density [18,21,23,24,26,36,38,39,44,51,57,60,61,66,79].

In most studies regarding fat percentage, it is above the minimum value allowed (3%) by local legislation. However, there are studies, such as those of [24,80], that find an amount of fat below this value. In the forest plot (Figure 6) with respect to the climatic season, it can be observed that the results found by [18,63], as well as that of [24], present greater variance with respect to the global mean. The percentage of milk fat is related to the nutrition that the animal has, as well as its breed [90], and is also dependent on the duration of grazing, the time of the year, the crop capacities and the type of pasture; the voluntary skimming of milk is one of the most common adulterations in milk [87], so the decreased values may be due to this characteristic.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of fat [14,16,17,18,21,23,24,26,28,33,35,38,39,42,44,51,53,57,60,61,63,76,77,79,80].

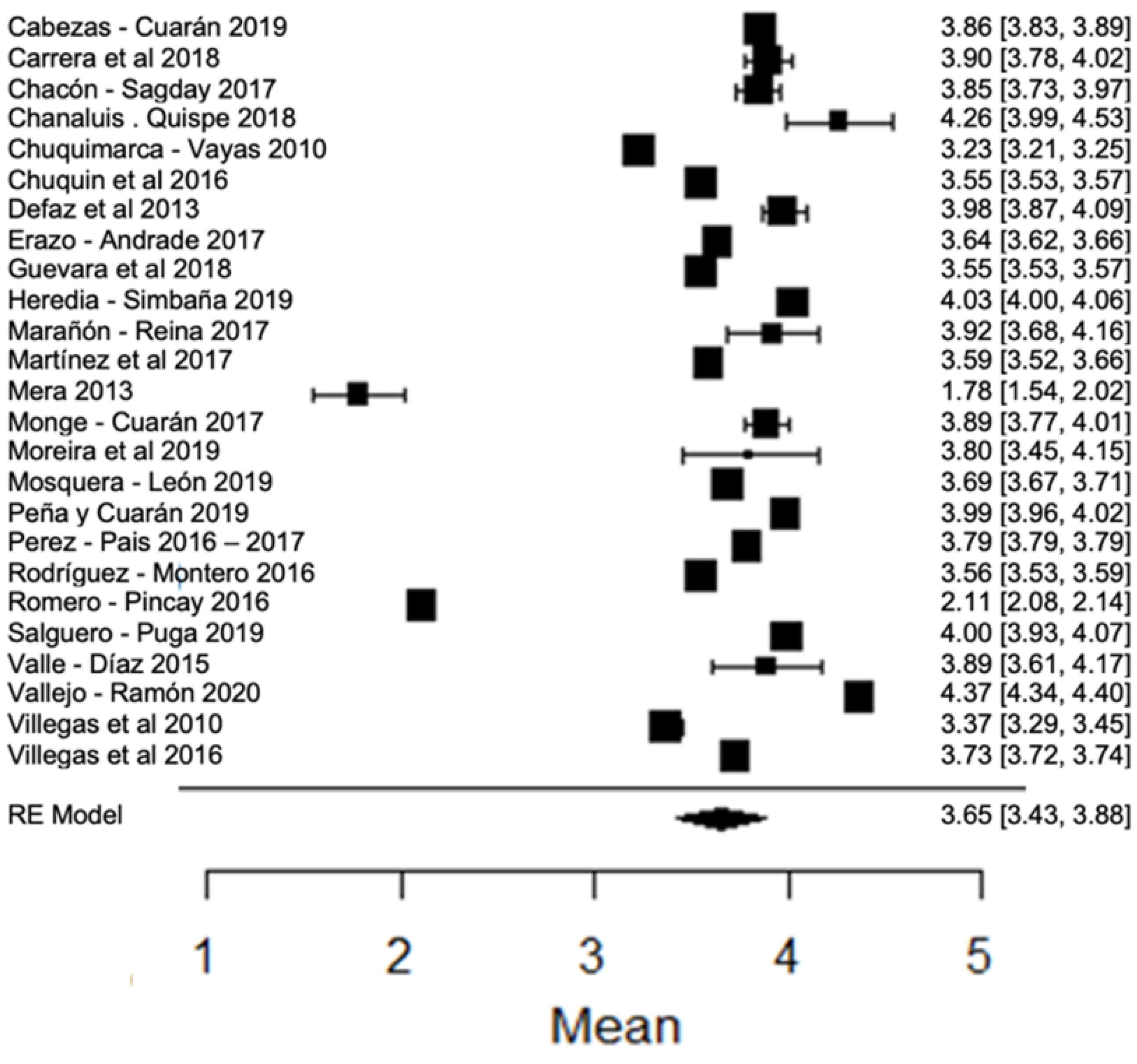

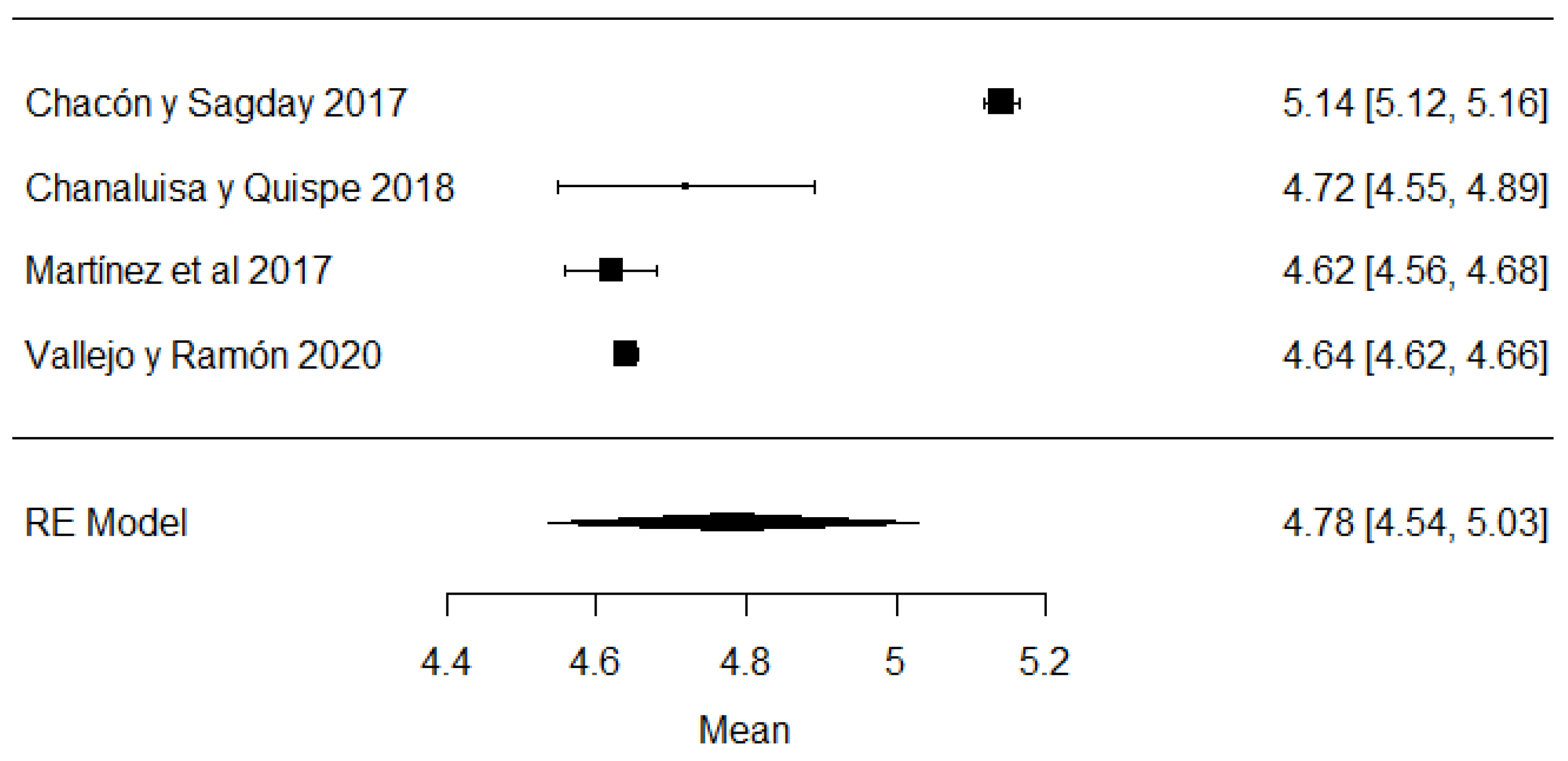

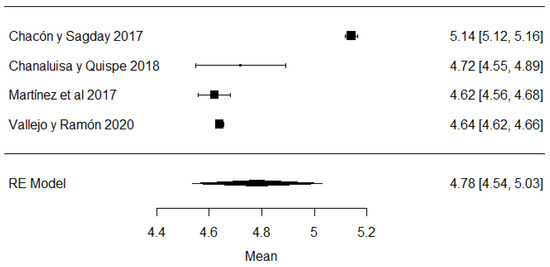

In the case of lactose values, all the studies are within the range of local regulations (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Lactose forest plot [42,51,57,77].

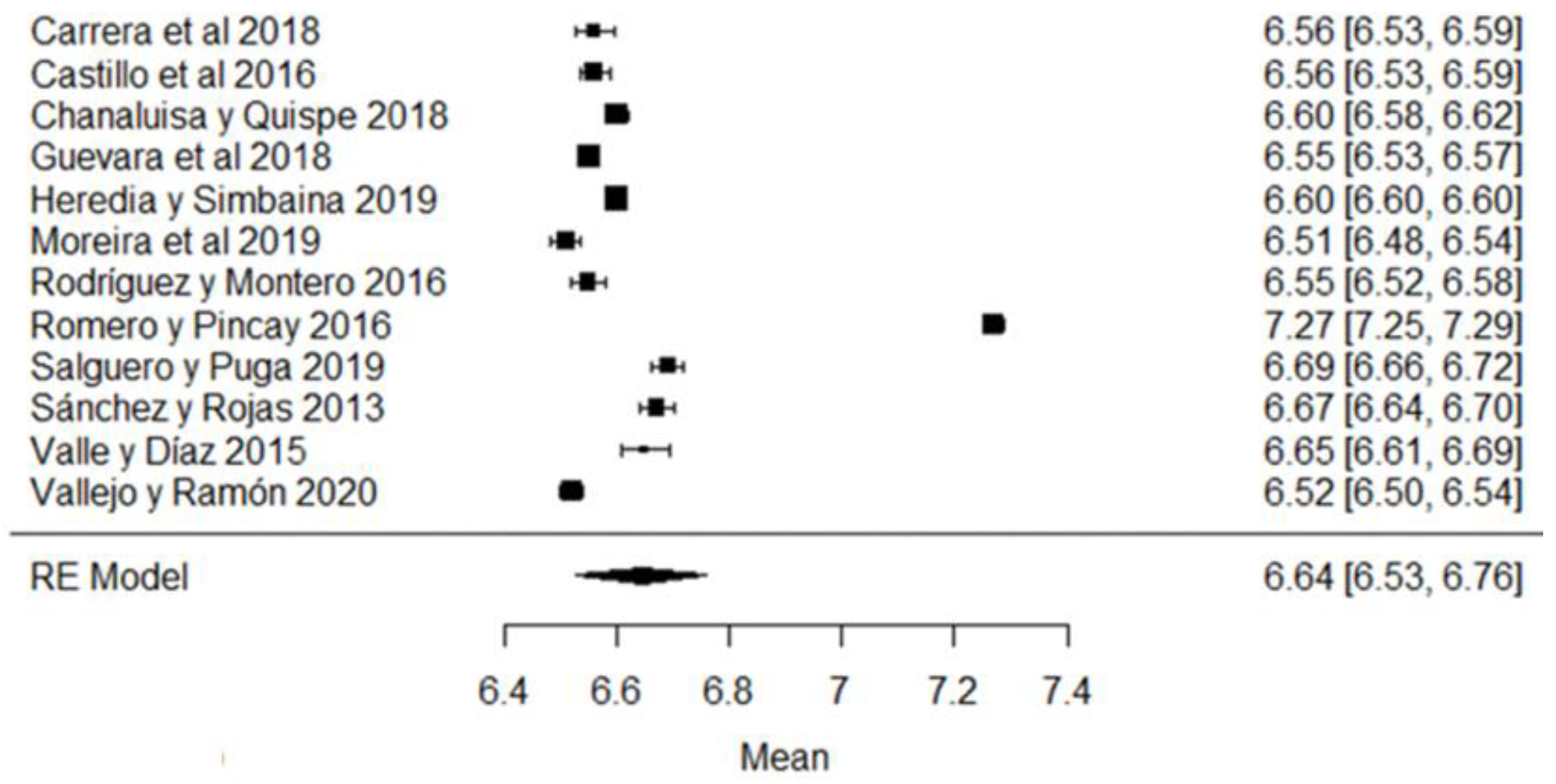

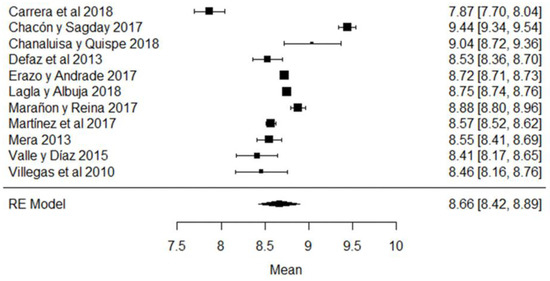

In the hydrogen potential (pH) parameter, the study of [24] has a mean above the stipulated value, while the studies of [18,23,26,43,44,57] are below the accepted minimum (Figure 8). The pH helps to determine certain indicators of milk quality, such as conservation, since changes in this variable can modify the stability of the protein, causing unpleasant flavors in the milk [91]. When a value below the average value is observed, it may be due to the presence of colostrum or bacterial decomposition; on the contrary, when values above the normal range are found, it is an indicator of possible mastitis or other factors due to adulterants such as neutralizers [92].

Figure 8.

Forest plot of pH [16,18,21,23,24,25,26,39,43,44,51,57].

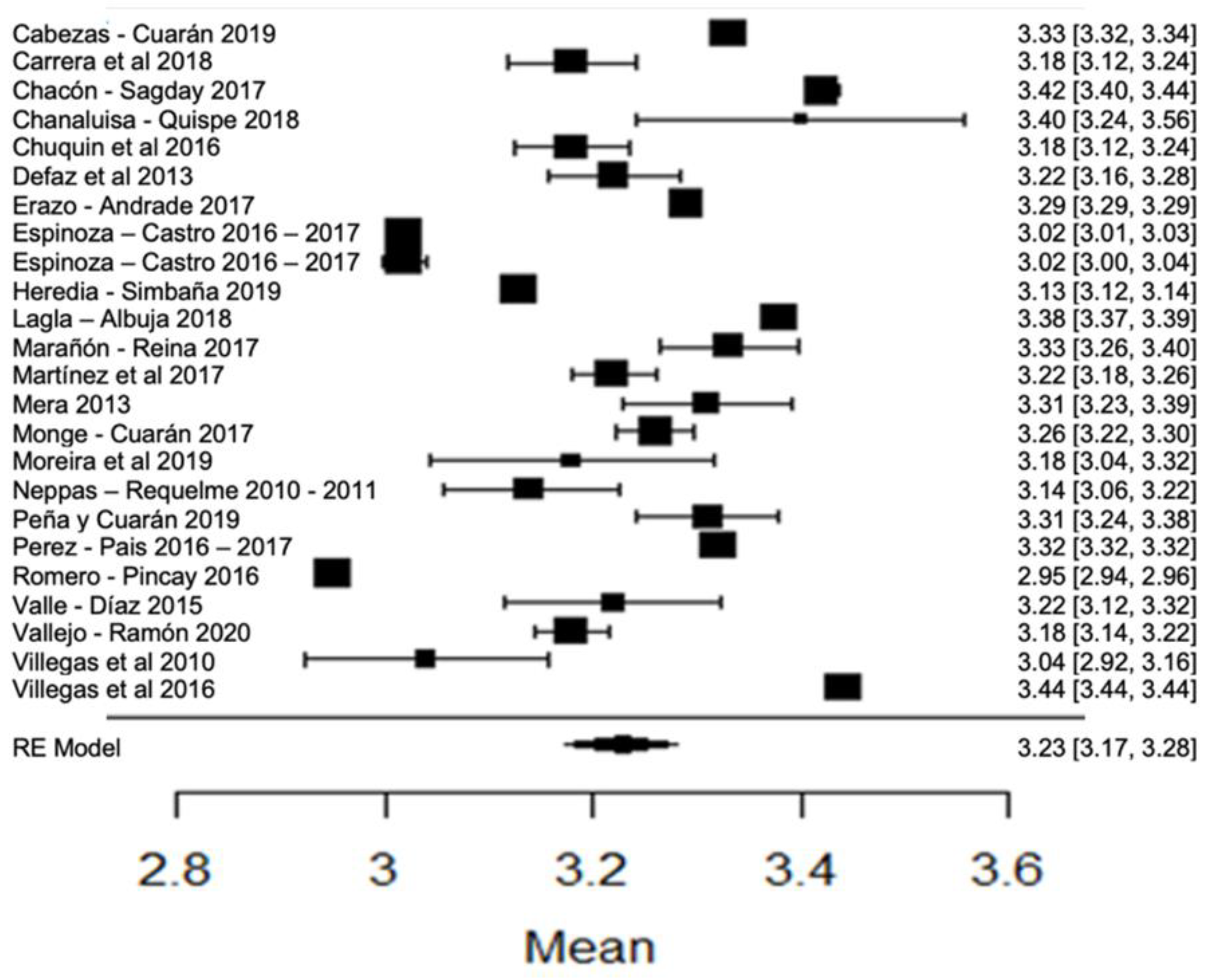

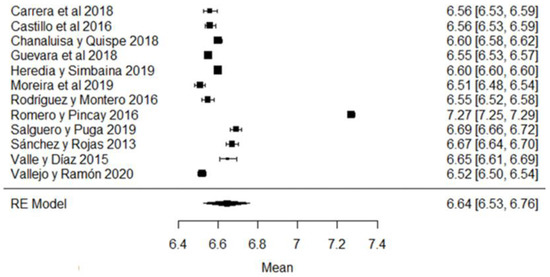

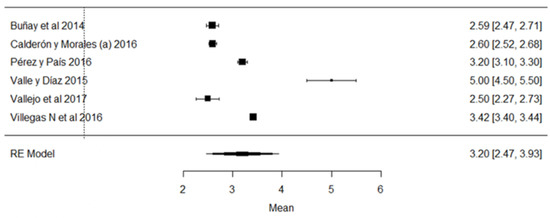

When analyzing the forest plot of protein (Figure 9), it can be observed that the average effect size is 3.23%. That is, the estimated global mean, and that of the majority of the studies, is within the range allowed by NTE INEN 9. However, the results found by [24,63], present greater variance with respect to the global mean (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Forest plot of protein [14,16,17,18,21,23,24,26,28,30,33,35,38,39,42,44,51,53,57,60,61,63,64,76,77,79,80].

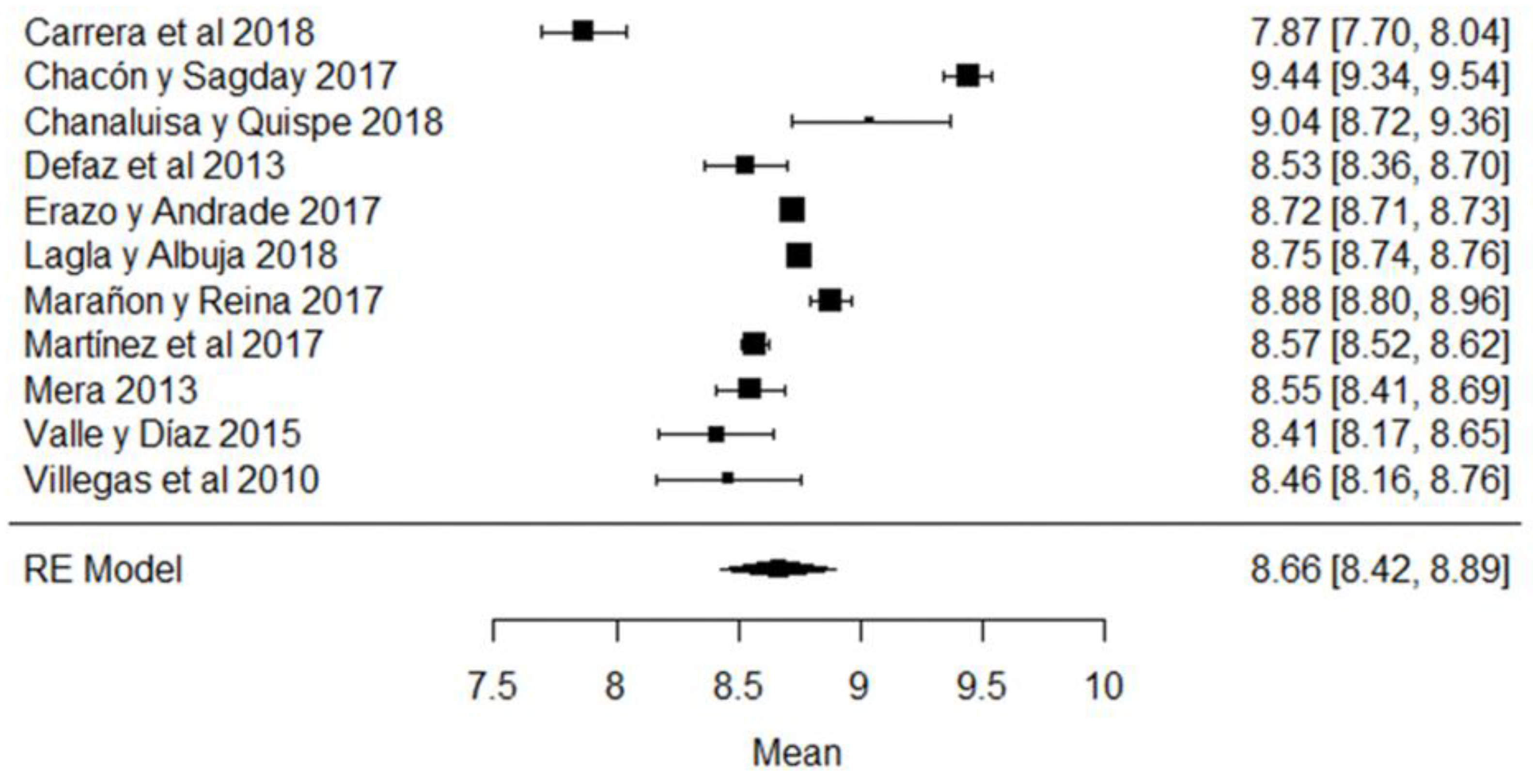

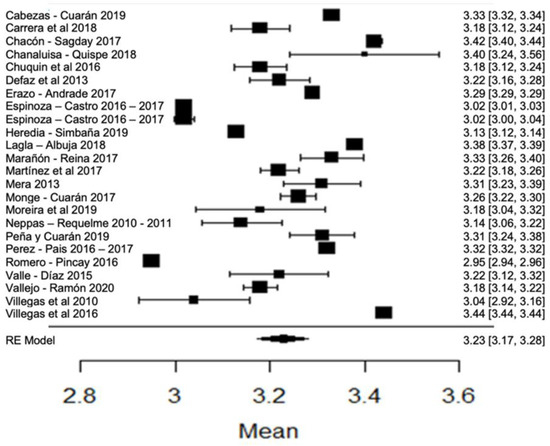

In the case of non-fat solids, the study whose mean is below what is required (Figure 10) is that of [44], while the results of [63,79] are those that present the greatest variance with respect to the global mean and which are evidenced in the forest plot of the climatic season (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Forest plot of non-fat solids [38,39,42,44,51,61,63,73,77,79,80].

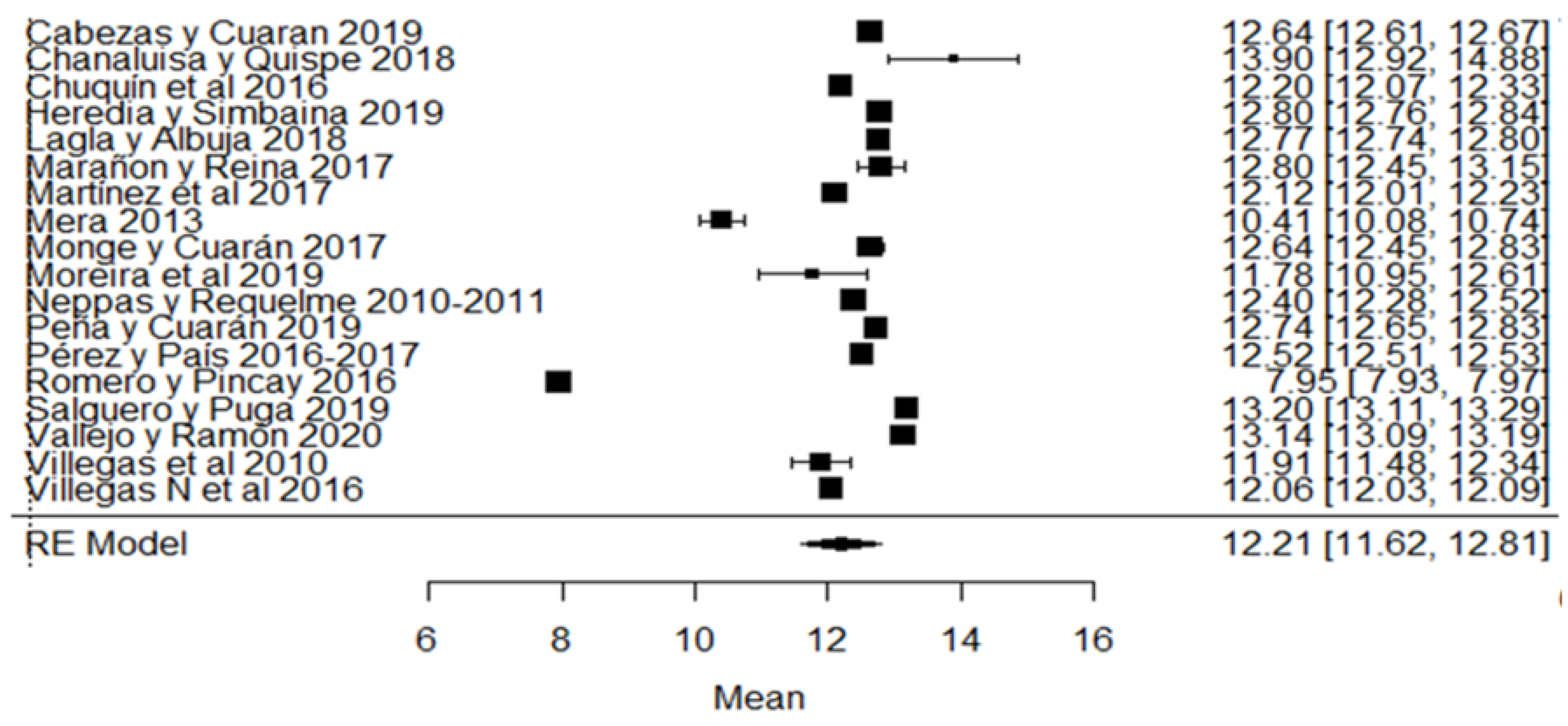

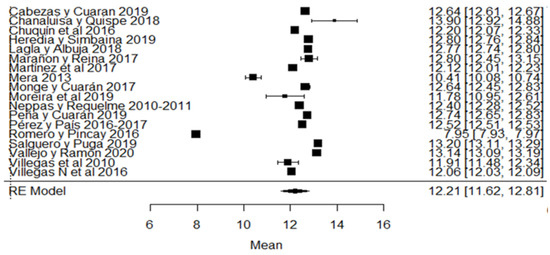

Likewise, for the total solids variable, the studies of [24,80] found a percentage of total solids below that required by the Ecuadorian standard (Figure 11). Regarding the climatic season, in addition to the aforementioned studies, we also find that [18] presents greater variance with respect to the global average (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Forest plot of total solids [14,16,17,18,21,24,30,33,35,38,51,53,57,73,76,77,79,80].

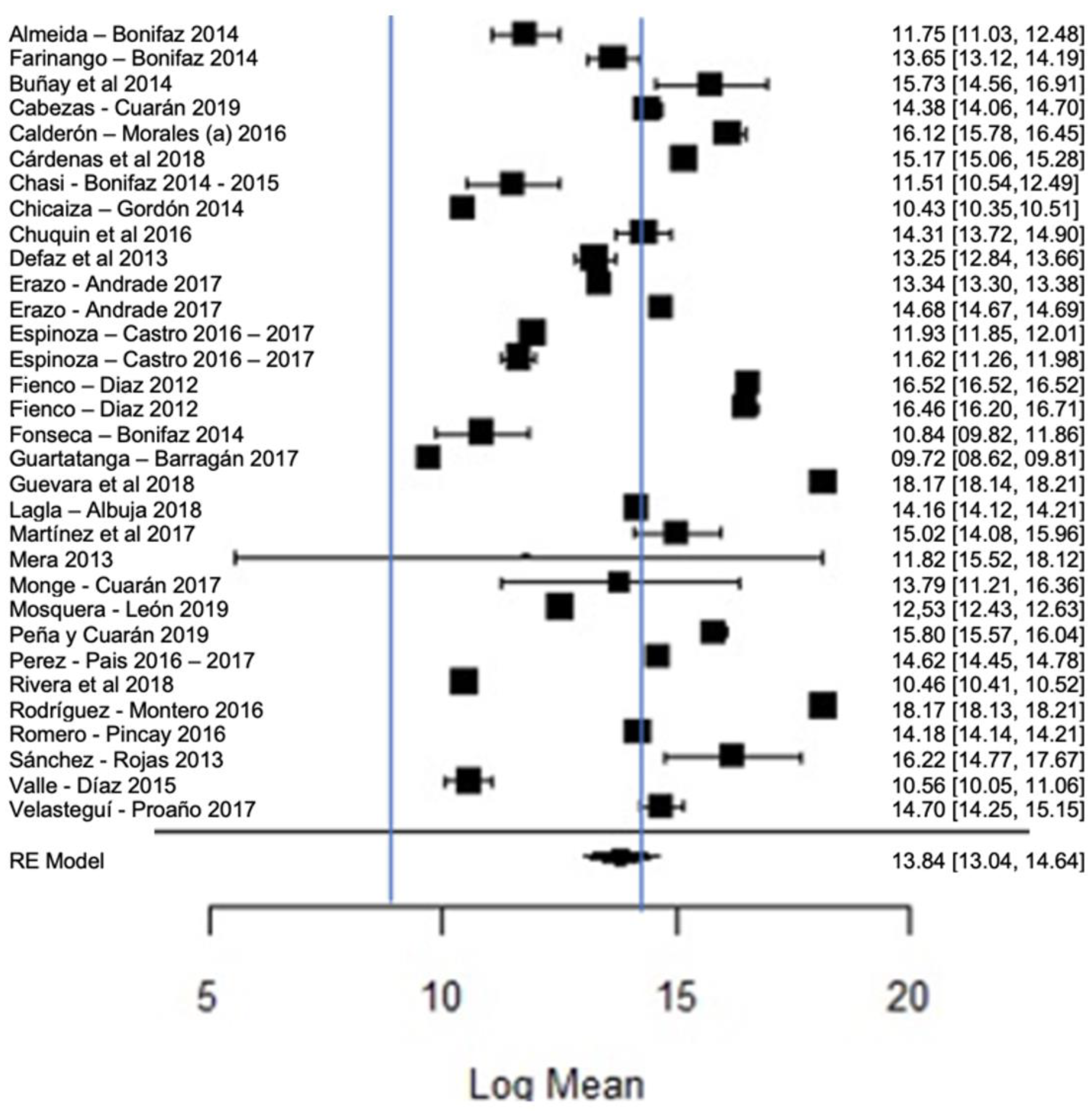

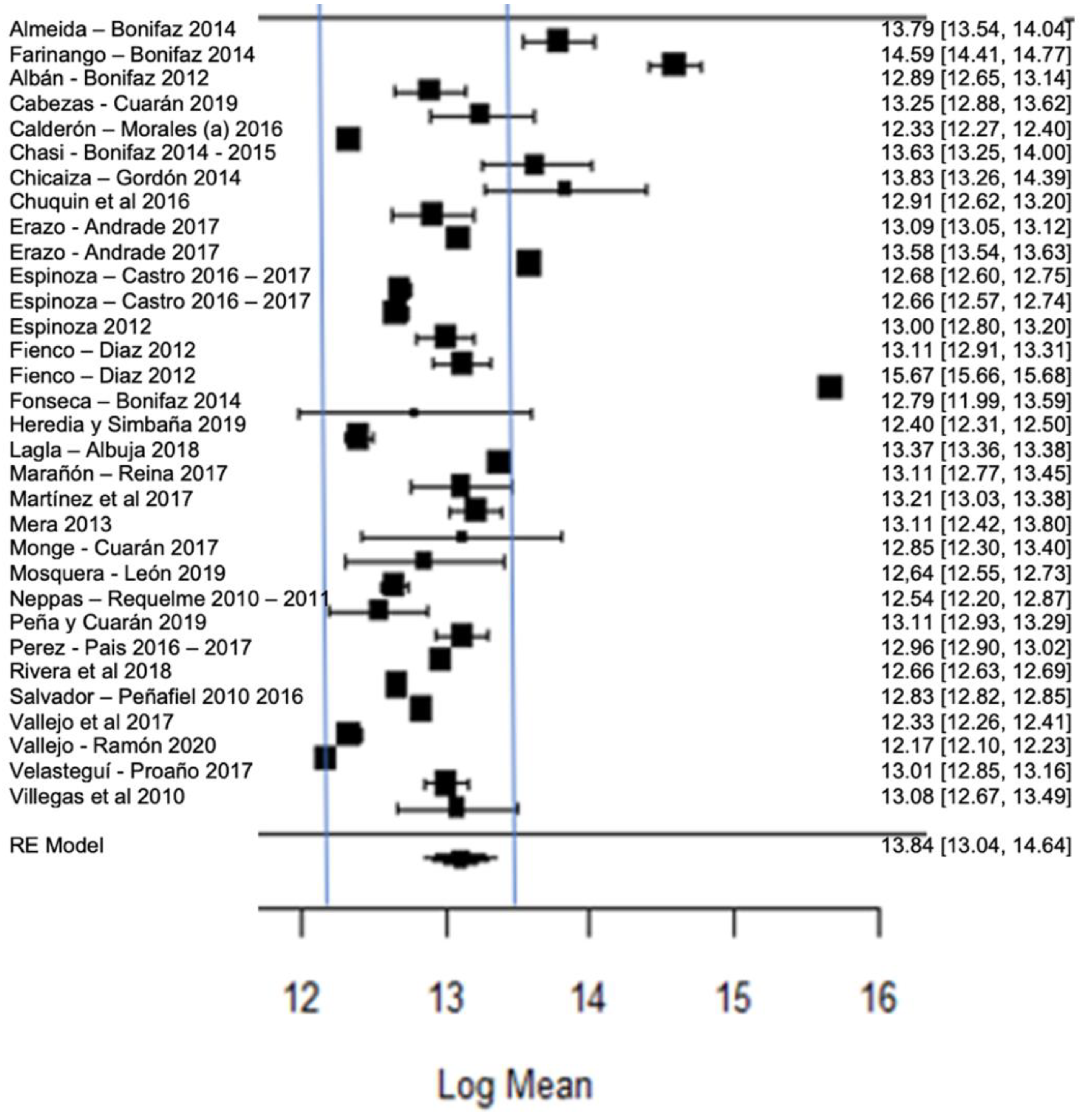

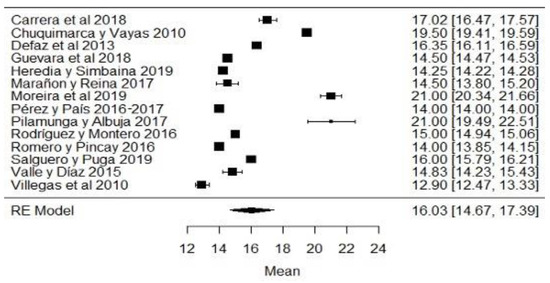

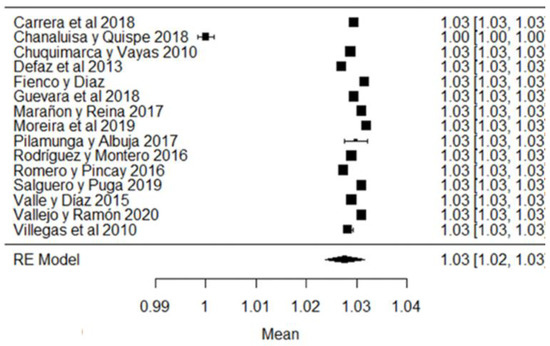

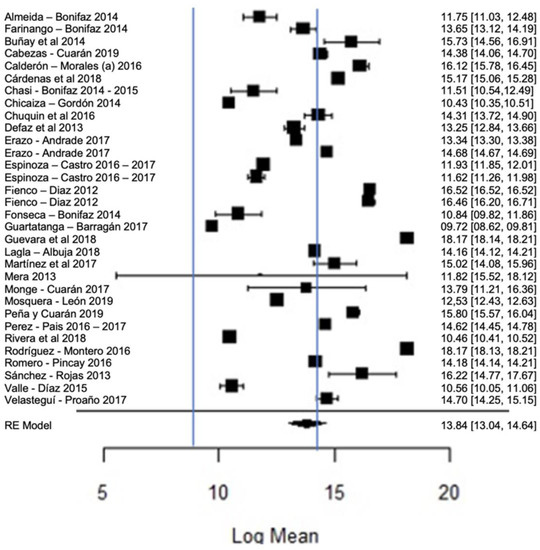

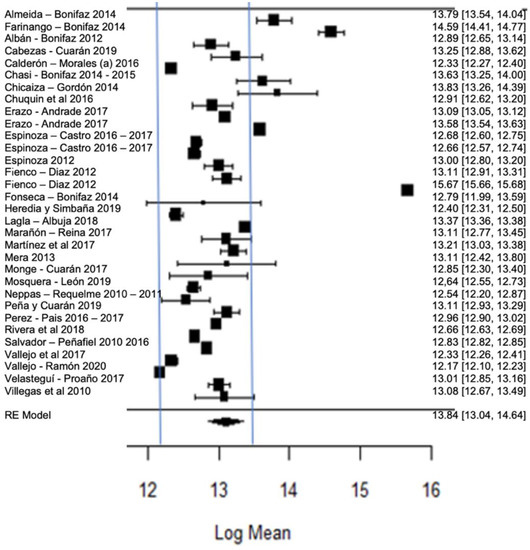

3.5. Forest Plot of Milk Hygienic Variables by Sampling and Region

Figure 12 shows the forest plot of the total bacterial count; the plot is elaborated based on a logarithmic scale. As for the results of the model, it can be observed that the average effect size of the bacterial count in graph A, represented by a rhombus, is 13.84, which is equivalent to (Exp13.84), that is, 1,024,791.77 CFU/mL. Therefore, the estimated global mean and several studies are within the maximum allowed by NTE INEN 9 (≤1,500,000.00 UFC/mL); there are several studies that present bacterial counts much higher than this allowed maximum, as in the case of [23,26].

Figure 12.

Forest plot of the bacterial count [14,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,33,35,39,47,52,53,54,56,58,61,63,64,66,67,68,71,73,76,77,80].

It should be emphasized that the range established by Ecuadorian regulations is relatively higher than that of other regulations, which means that there is a high presence of bacteria in raw milk in Ecuador; this is probably related to failures in hygiene, in the disinfection of production areas and milking procedures or in materials or equipment; bacterial growth in milking equipment; contamination by dirty cow udders; the milking of cows with mastitis; inadequately cooled milk (failure to control the storage temperature); or the quality of the water used, among others [93,94]. The importance of milk containing low bacterial counts lies in the fact that certain bacteria survive thermal processes, which could affect, in some way, the taste, texture or shelf life of milk [95], since bacteria can cause the spoilage of milk, as well as diseases that affect humans [96]. Therefore, when high microbial contents of milk are found, milk procurement needs to be improved [97]; for example, with proper disinfection, cleaning, storage and transportation of raw milk, it is guaranteed to be of good quality for consumption; likewise, by performing good milk handling practices, by training both the producers and actors involved in marketing and transportation, the quality of milk can be improved [98]. The pasteurization of milk seeks to eliminate pathogenic bacteria and guarantee the health of consumers, and it has been found that this heat treatment has a minimal effect on the nutritional characteristics of milk [99].

Reductase is not a natural enzyme in milk, but its presence is constant due to bacterial contamination, so its analysis, known as the methylene blue reduction time, is an indirect test of microbial contamination in milk. In the vast majority of samples, its presence was higher than the minimum values allowed by local legislation (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Forest plot of reductase presence [19,35,38,39,52,54].

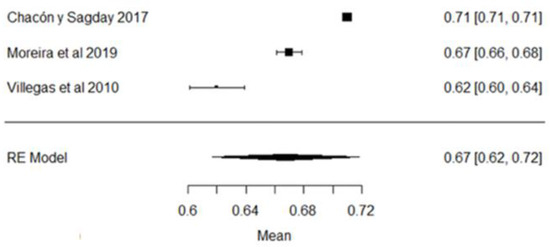

Figure 14 shows the forest plot of the somatic cell count; the plot is elaborated based on a logarithmic scale. As for the model results, the mean effect size of the somatic cell count in plot, represented by a rhombus, is 13.10, which is equivalent to (Exp13.10)—ergo, 488,942.41 CS/mL—which is represented by the rhombus. There are values found by authors, such as those of [57], that are far from the global mean, but are still within the range of the Ecuadorian standard, which establishes a maximum permissible level of ≤700,000 CS/mL.

Figure 14.

Forest plot of somatic cell counts [14,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,33,35,38,39,47,52,53,54,56,58,61,63,64,66,67,68,71,73,76,77,80].

Likewise, several studies present greater variance with respect to the global average, as is the case in [63,65,70], although the averages mostly comply with local legislation; however, if the international requirements (≤200,000 CS/mL) of milk quality are taken into account, it can be noted that very few findings would be within this range.

The somatic cell count in milk indicates the hygienic sanitary quality of the mammary gland, and is also considered a health indicator since the somatic cell count increases in direct proportion to the severity of the infectious disease [100,101]. Likewise, it directly affects milk production since it decreases milk production by 2.5% for each increase of 100 thousand somatic cells from the 200 thousand that are considered normal; therefore, it could be expected that a herd with a count of 500 thousand CS/mL would have a 7.5% decrease in production due to subclinical mastitis [102].

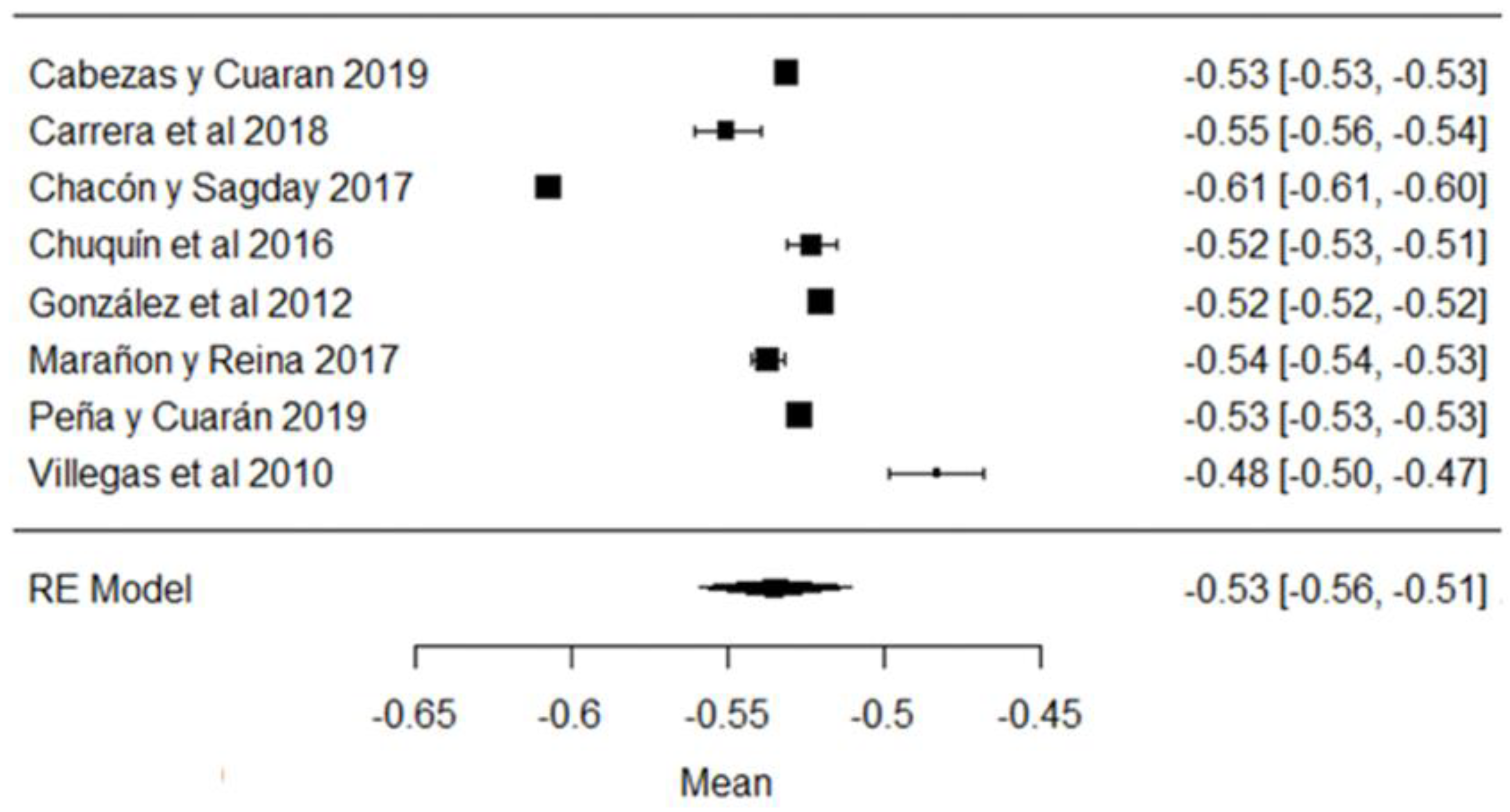

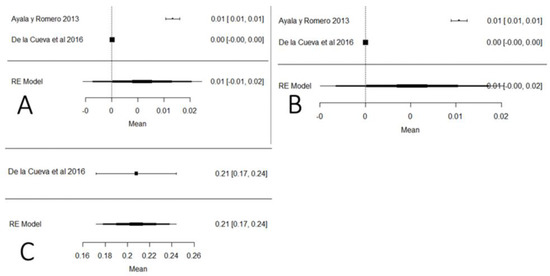

3.6. Forest Plot of Adulterant and Contaminant Variables in Raw Milk by Sampling and by Region

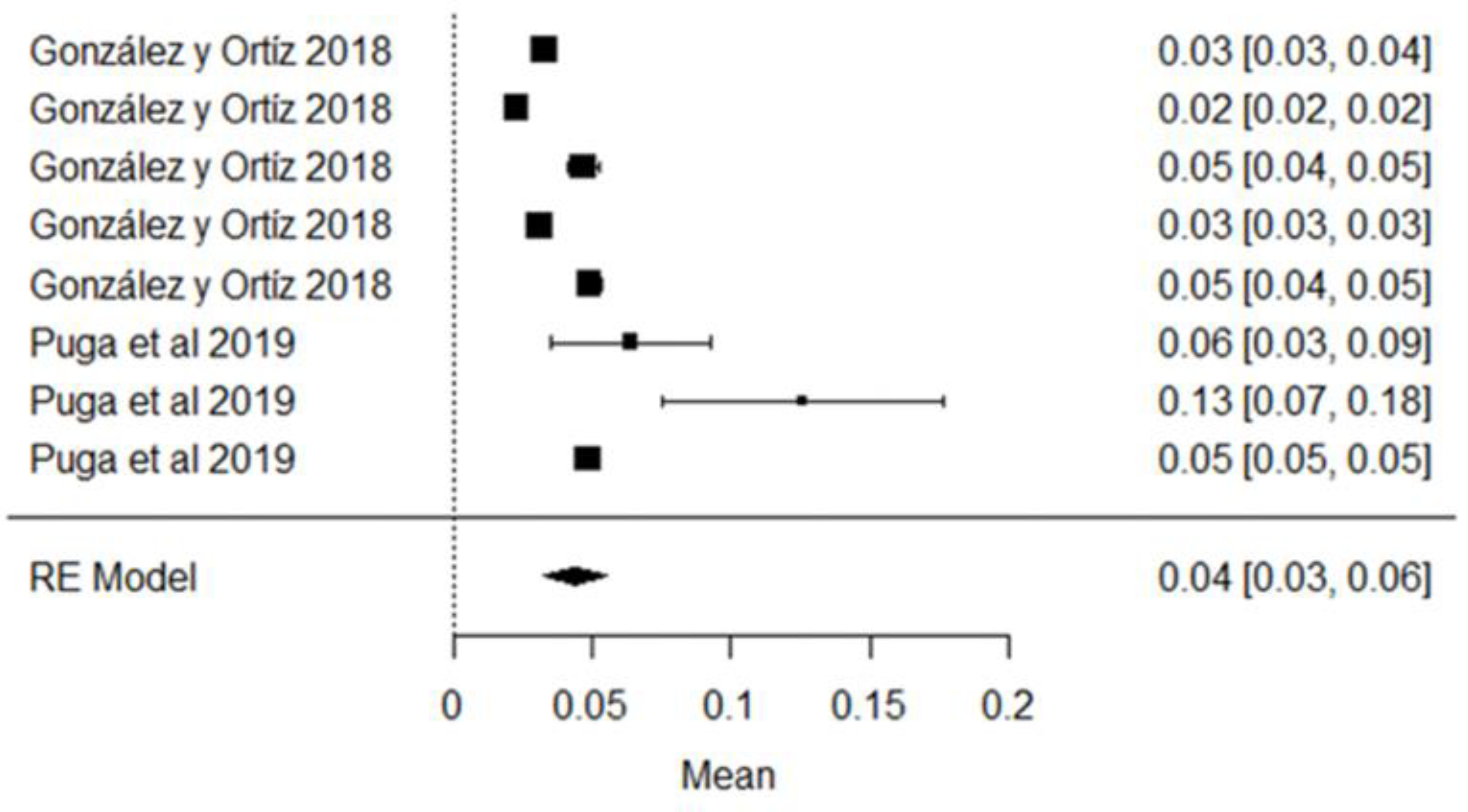

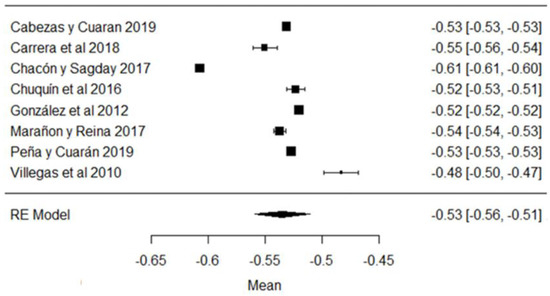

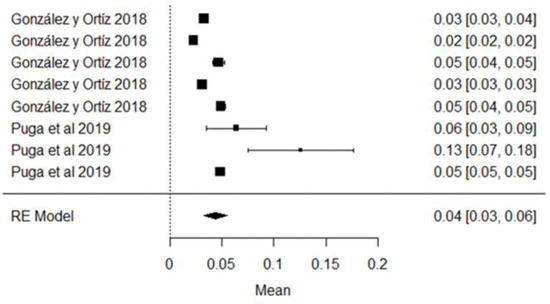

Regarding Aflatoxin M1, the mean is 0.04 μg/kg and its graphic representation (rhombus) is on the right side of the unit value, which means that in the raw milk analyzed in these studies, the mycotoxin is present in different quantities, most of which do not exceed the 0.5 μg/kg allowed by the NTE INEN 9 standard; however, if compared with the European standard (MLR = 0.05 μg/kg), two studies conducted by the authors of [81] in the province of Manabí and Pichincha, exceeded this limit; they also observe that climatic region is a factor related to the presence of contaminants in raw milk, which are numerically higher in the coastal region, but not statistically significant (Figure 15). AFM1 is the only mycotoxin with maximum limits allowed in milk [103], since it can be hepatotoxic and carcinogenic [104], and it is not destroyed by the pasteurization or technification of dairy products [105].

Figure 15.

AFM1 forest plot [40,81].

In the case of studies on the presence of added water, it was found that in the same studies, added water was present, which is illegal according to Ecuadorian legislation (Figure 16) and is carried out with the intention of increasing the volume of milk.

Figure 16.

Forest plot of added water [39,61,63].

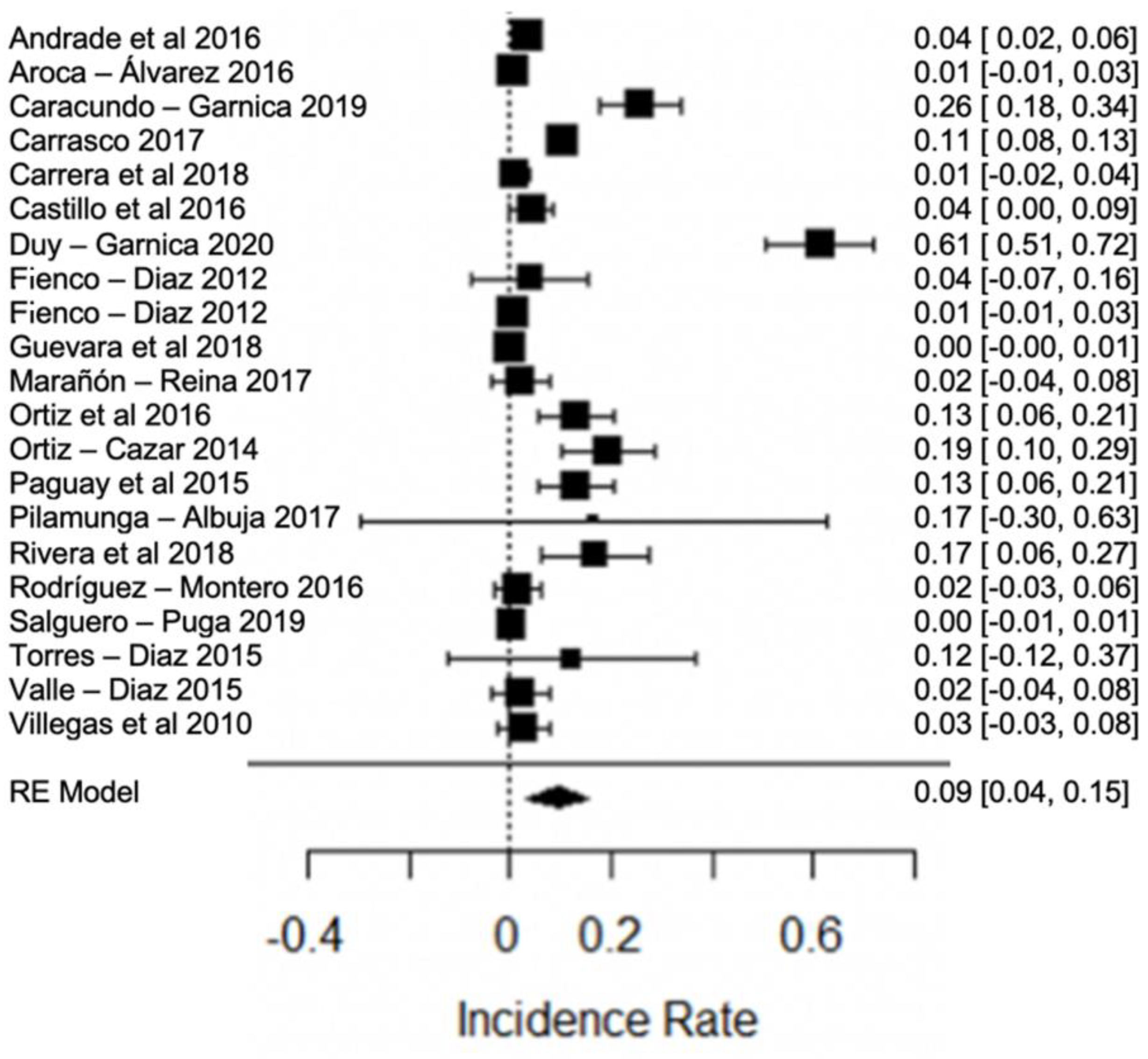

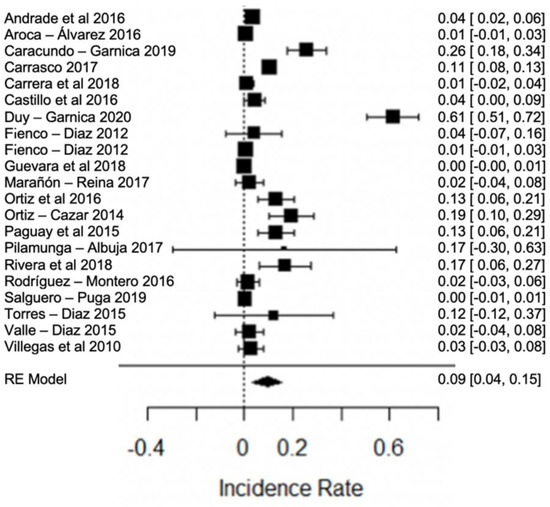

One of the major concerns is the high presence of antibiotic residues in the studies analyzed. In Figure 17, the forest plot of antibiotics in raw milk, where the presence of this contaminant was found, shows great variation among the studies, with between 10% and 72% positive samples in different provinces of Ecuador.

Figure 17.

Forest plot of antibiotic [21,23,26,27,31,32,36,38,39,43,44,46,48,49,50,62,66,79,82].

These antimicrobials are considered one of the highest-risk contaminants, as they are widely used in cattle for the control of various diseases, and are also used in sub-therapeutic doses that are added to feed to act as growth promoters [106]. Despite being an important tool to combat diseases, excessive use and misuse can induce residues in milk when withdrawal times are not respected [107]. In this way, they become a potential risk, causing serious problems for their consumers, such as hypersensitivity, allergic reactions, bacterial resistance. In addition to this, in industrialization, it affects cheese and yogurt production, directly inhibiting the bacterial fermentation process [108,109]. These data show that control measures are inefficient in the dairy industry, so their permanent control is essential for all those involved in the dairy chain [3].

For these reasons, food control and safety agencies establish standards and monitoring programs for the maximum permissible limit of antibiotic residues in raw milk. Heat treatment plays an important role in preventing the development of antimicrobial resistance. Although antibiotic molecules are not completely degraded, this process is efficient in destroying 99.99% of bacteria that may contain resistance genes, thus preventing the multiplication of these types of bacteria; however, it is not known exactly whether the resistance genes contained in the bacteria are viable, even after pasteurization, and theories are currently being investigated [110].

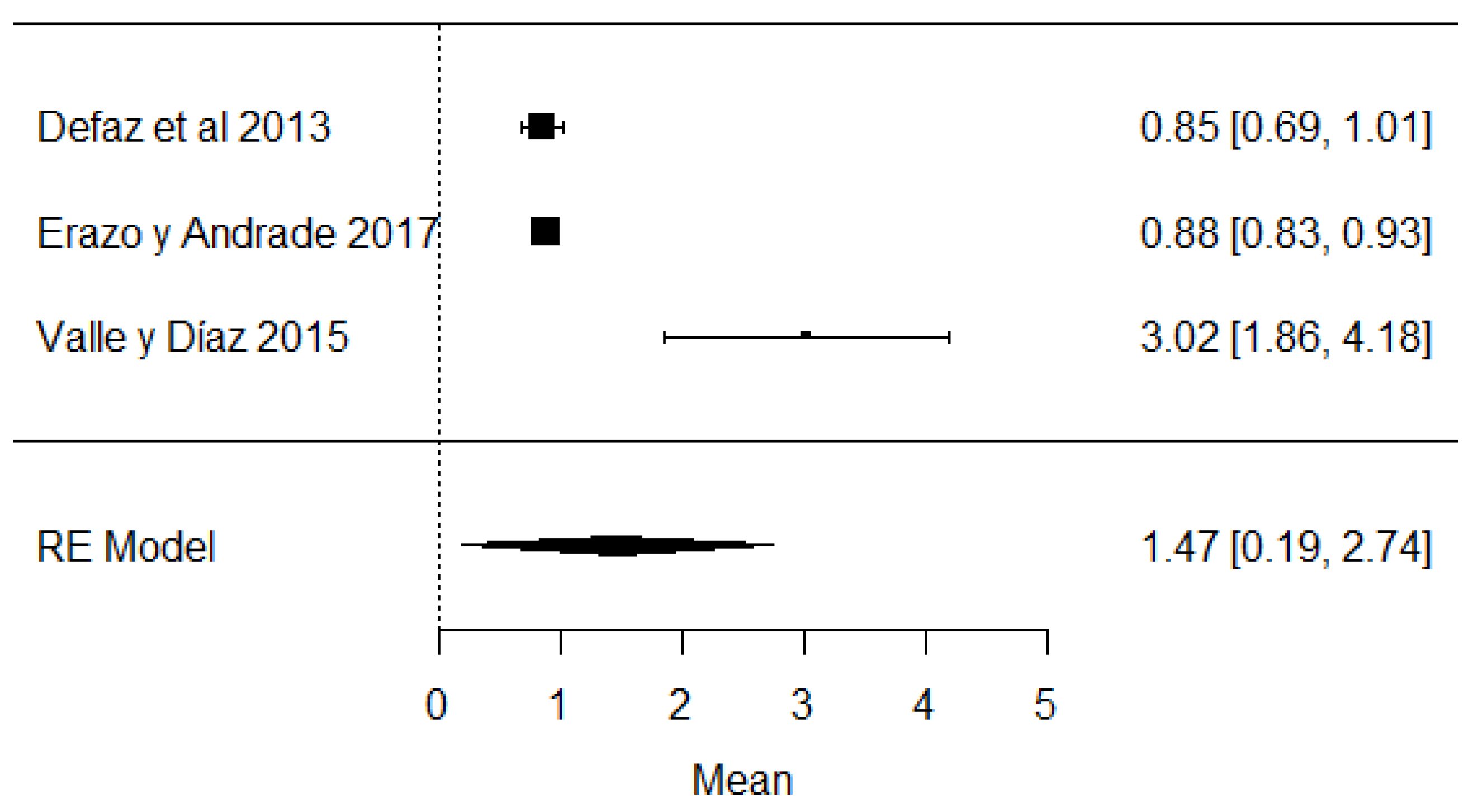

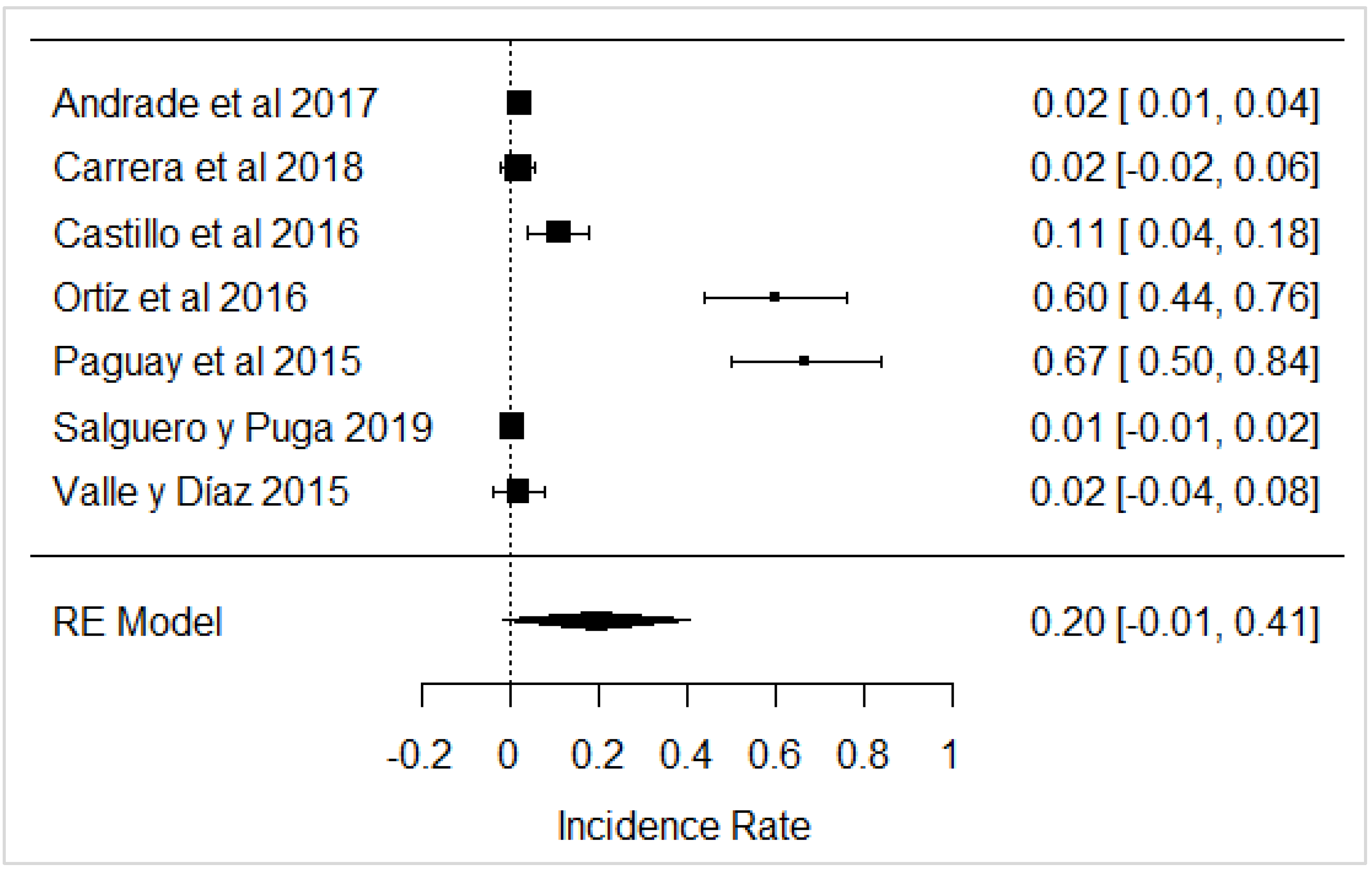

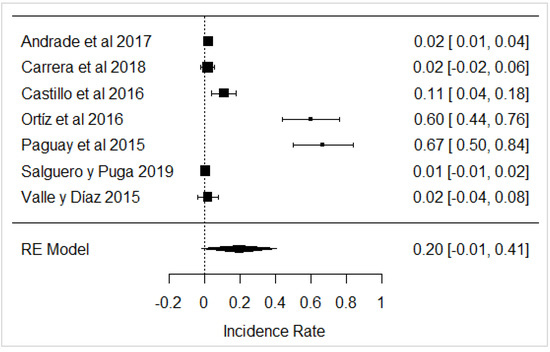

In the case of neutralizing substances, most of the samples did not show the presence of these substances in the milk analyzed, but in some investigations, the use of these substances was evident, as in the results obtained in [31,32,43], as shown in Figure 18. These chemicals are used to mask the acidity of raw milk, and generally have serious consequences for public health in high doses as they are able to cause the development of kidney stones, or become deposited in body fluids and soft tissues [111,112].

Figure 18.

Forest plot of neutralizing agents [21,31,32,39,43,44,82].

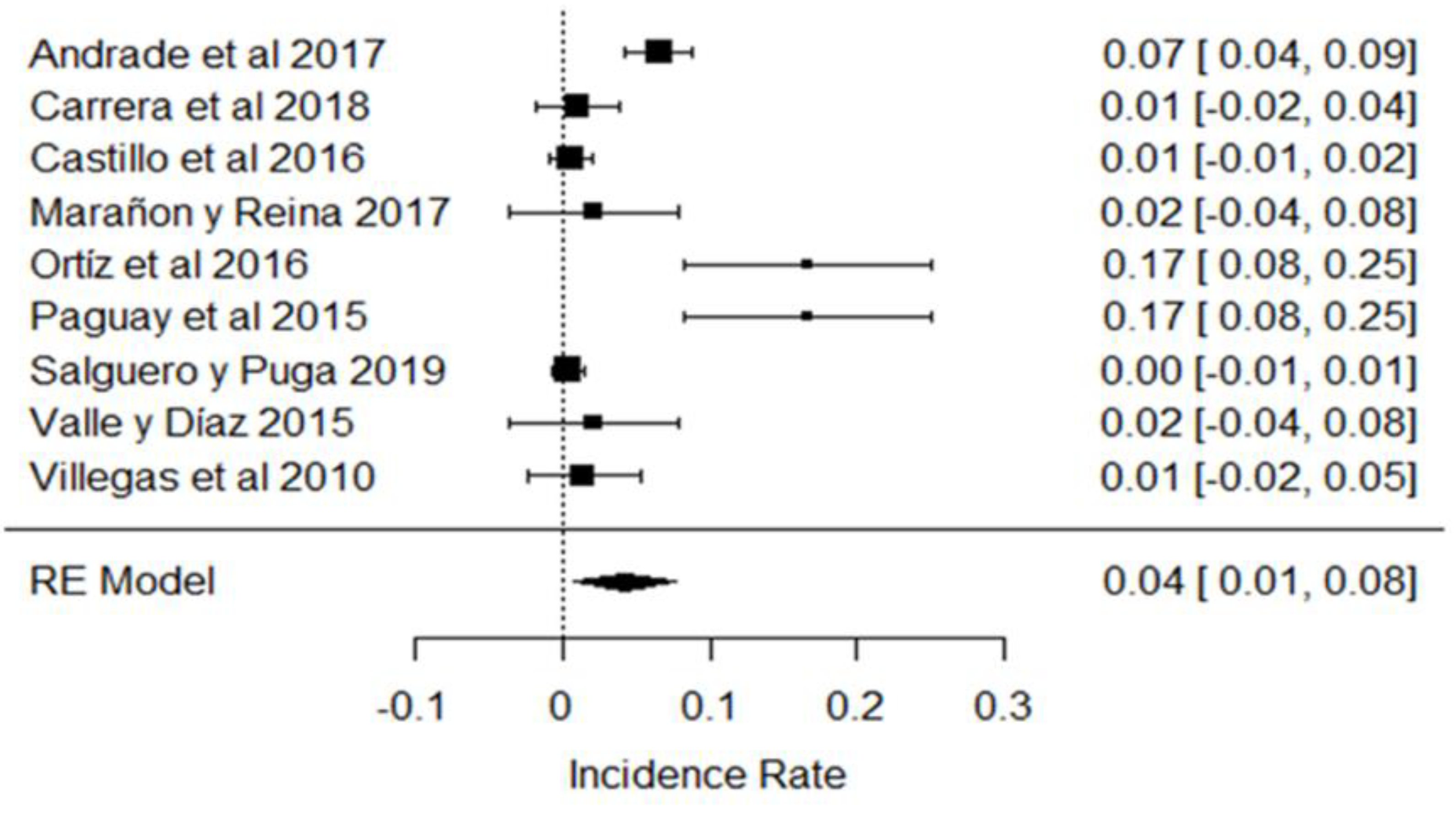

Regarding the presence of hydrogen peroxide (which is not allowed by Ecuadorian legislation), there is wide variability among the studies; for example, in the research of [31,32,82], its levels are farthest from the zero point or the line of incidence, so they disagree with the majority of studies (Figure 19). In Ecuador, the use of hydrogen peroxide is prohibited because it is used to mask the acidity of milk [111,112]; however, there are studies that indicate the benefits of using it to preserve milk for up to 8 h at room temperature without losing its organoleptic characteristics, even in the Ecuadorian tropics, where ambient temperatures can be above 25 °C [113].

Figure 19.

Forest plot of the presence of peroxides [21,31,32,38,39,43,44,79,82].

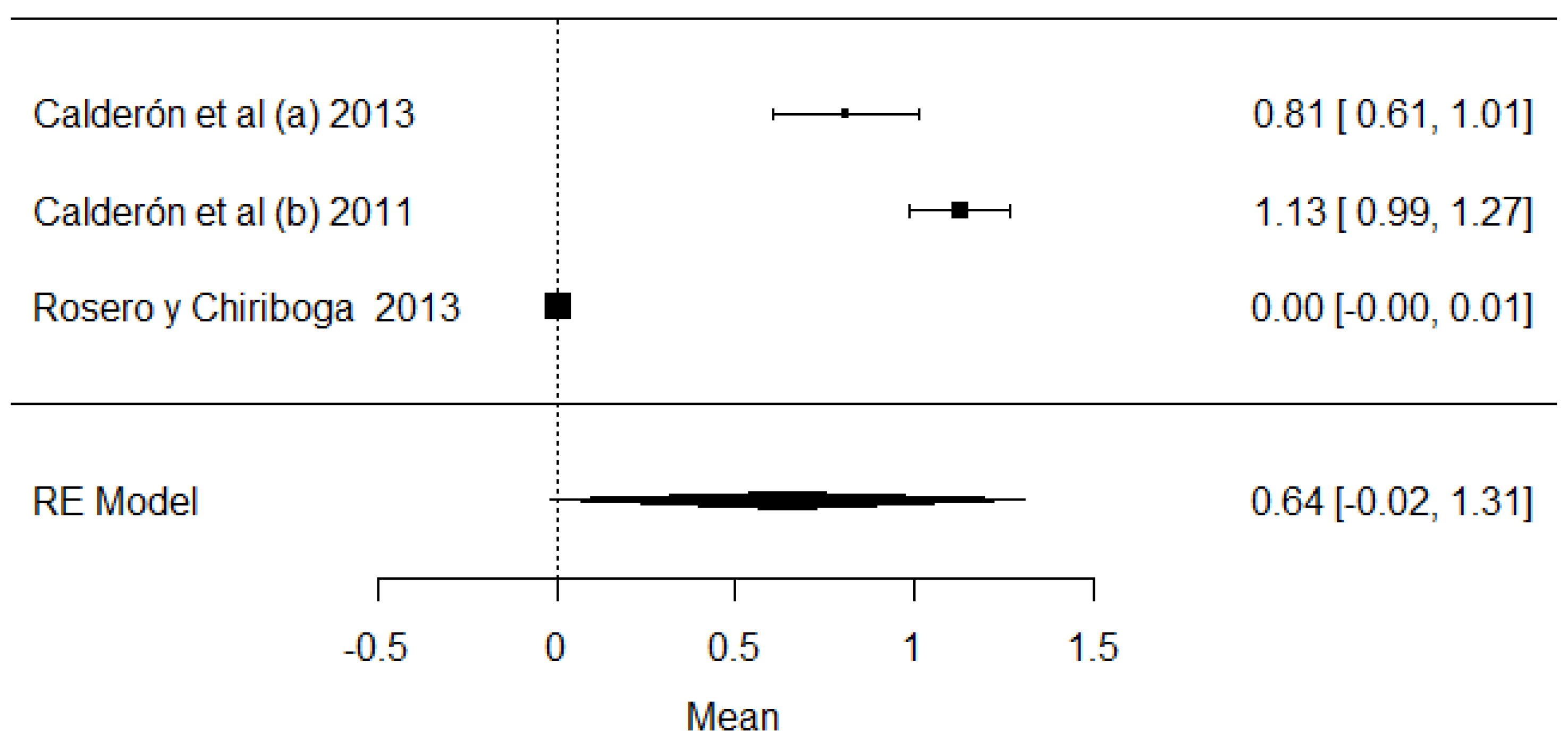

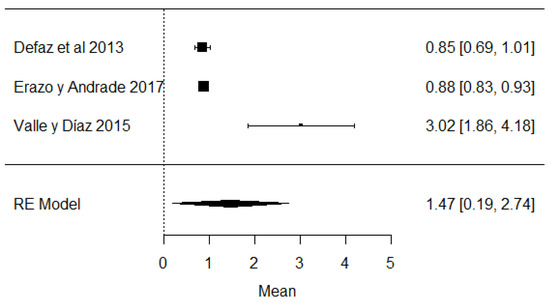

Regarding the fern toxin, called ptaquiloside, studies were found that demonstrate the presence of this variable in the samples analyzed in Ecuador (Figure 20). Cattle that ingest ferns can develop several diseases such as hemorrhagic problems, hematuria and even carcinomas, which are the carcinogenic problems that can affect humans the most [114].

Figure 20.

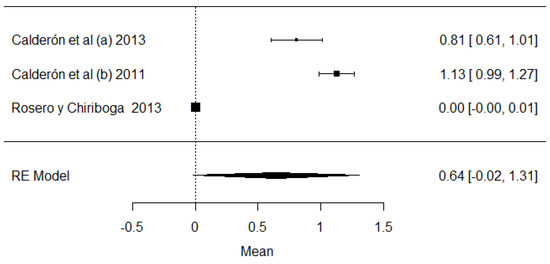

Forest plot of ptaquilosides [15,22,70].

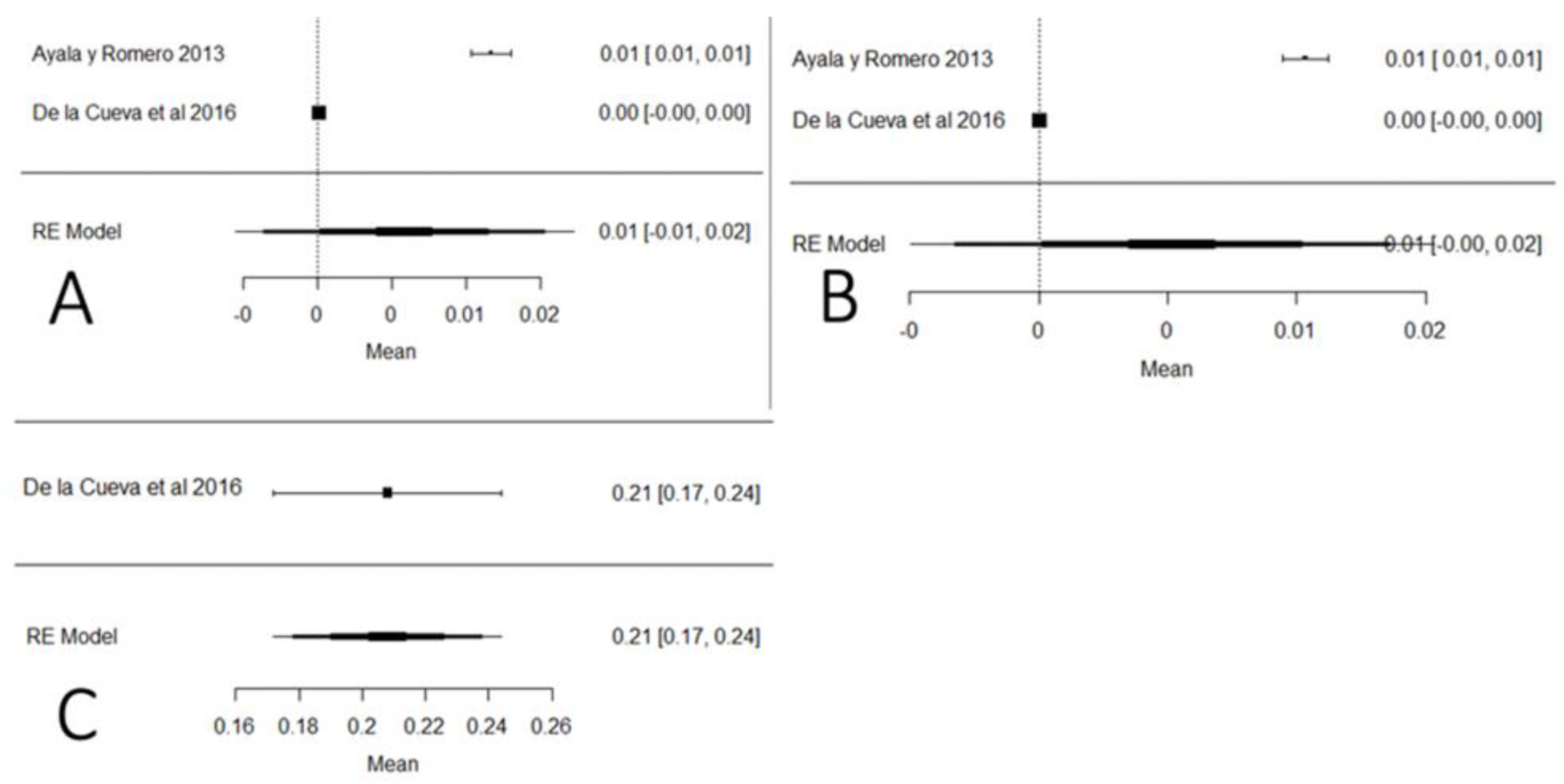

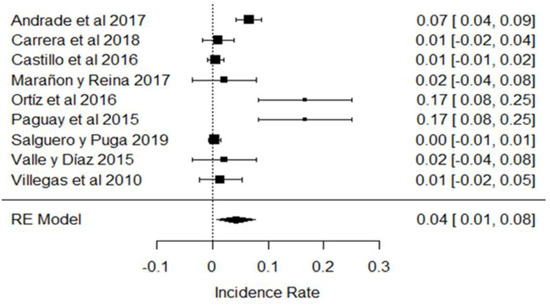

Figure 21 shows the studies carried out on heavy metals in Ecuador (mercury, arsenic and lead). In the case of mercury and arsenic, neither the Ecuadorian regulations nor the Codex Alimentarius indicate maximum permissible values for raw milk, so the results were interpreted in relation to drinking water (0.001 mg/kg). The mean of these studies crosses the value of the plot unit, which means that the results do not present a relevant significance value to determine the presence of these heavy metals; this does not happen with lead, for which the majority of values are above the maximum stipulated by local and international legislation. Regarding climatic region, the highest presence of arsenic and mercury was determined in the coastal region, while for lead, there is only one study in the Sierra region. The presence of these heavy metals has a natural and anthropogenic origin. Naturally, it is documented that in localities where there are volcanic eruptions, the level of lead rises in the environment. Anthropogenic activities such as mining and refining remove high levels of heavy metals in the environment [115]. Heavy metals have genotoxic, nephrotoxic and carcinogenic properties, and also cause severe oxidative stress [116].

Figure 21.

Forest plot for the presence of heavy metals: (A) mercury; (B) arsenic; (C) lead [12,83].

Based on the findings of this study, the presence of adulterants and contaminants in raw milk between 2010 and 2020 in Ecuador is evident. The findings are of great concern for producers, consumers and regulatory agencies, since the averages of the contaminants analyzed in this systematic review were: AFM1 (0.04 μg/kg), antibiotics (0.09 μg/L), lead (0.208 mg/kg), arsenic (0.01 mg/kg) and mercury (0.01 mg/kg). In addition to these substances, it should be mentioned that there were studies of public health relevance that reported the presence of several types of contaminants in raw milk, such as eprinomectin, zearalenone and ptaquilosides. Another issue is that thermal treatments are not effective at disintegrating these types of contaminants due to their thermal stability [117].

4. Conclusions

The systematic review and meta-analysis of 73 studies of the milk quality parameters of raw milk produced in different regions of Ecuador, between 2010 and 2020, indicates that there is great variability among them (I2 > 90%) with respect to the different variables analyzed; we found better compliance with the Ecuadorian regulations in the physicochemical parameters, especially the composition parameters such as fat (mean: 3.69%), protein (mean: 3.2%), lactose (mean: 4.78%), ash (mean: 0.6725%), non-fat solids (mean: 8.66%) and total solids (mean: 12.24%). Regarding hygienic quality (total bacterial count and somatic cell count), the local regulations are very lenient compared to other regulations, which means that there is a high presence of bacteria in Ecuadorian raw milk (mean: 6,878,541.1 UFC/mL); this is probably related to hygiene failures in milking and in the storage and transportation of milk, and the high somatic cell count (mean: 695,736.1 CS/mL). Likewise, adulterants and contaminants in raw milk have been determined in several studies, which is a cause for concern (for example lead (mean: 0.208 mg/kg), AFM1 (mean: 0.421 µg/kg), antibiotics (14.55%), arsenic (mean: 0.005 mg/L) and mercury (mean: 0.00009 mg/L)). It is necessary to take corrective actions, through training in producers, to improve the quality of milk produced in Ecuador, which will benefit the public health of consumers and the profitability of livestock farms.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/foods11213351/s1, Table S1: Information on the studies and authors used in the research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P.-T. and D.D.l.T.; methodology, B.P.-T., L.R., E.A.V. and D.D.l.T.; software, L.R.; validation B.P.-T., L.R., E.A.V. and D.D.l.T.; formal analysis, B.P.-T. and L.R.; investigation, B.P.-T., V.Á., S.B., A.G., D.L., E.A.V. and D.D.l.T.; resources, B.P.-T., V.Á., S.B., A.G., D.L., E.A.V. and D.D.l.T.; data curation, B.P.-T. and D.D.l.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P.-T., E.A.V. and D.D.l.T.; writing—review and editing, B.P.-T., V.Á., S.B., A.G., D.L., E.A.V. and D.D.l.T.; supervision, B.P.-T.; project administration, B.P.-T. and D.D.l.T.; funding acquisition, B.P.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the General Directorate of Research of the Universidad Central del Ecuador for registration of this study under project code: 09E-2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fernandez, J.; Zafra, J.; Goicochea, S.; Taype, A. Aspectos Básicos Sobre La Lectura de Revisiones Sistemáticas y La Interpretación de Meta-Análisis. Acta Médica Peru. 2019, 36, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá-López, F.; Tobías, A. Metaanálisis de Ensayos Clínicos Aleatorizados, Heterogeneidad e Intervalos de Predicción. Med. Clin. 2014, 142, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahramian, B.; Sani, M.A.; Parsa-Kondelaji, M.; Hosseini, H.; Khaledian, Y.; Rezaie, M. Antibiotic Residues in Raw and Pasteurized Milk in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AIMS Agric. Food 2022, 7, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G.; Díaz, P.; Bonifaz, N. Milk Quality Management of Small and Medium Cattle Ranchers of Collection Centers and Artisan Cheese Factories, for Continuous Improvement. Case Study: Carchi, Ecuador. Granja 2018, 27, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Producción y Productos Lácteos. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/dairy-production-products/production/es/ (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería, Acuacultura y Pesca. MAGAP Socializa Acuerdo 394 Sobre la Calidad y Normativa de la Leche. 2011. Available online: https://www.agricultura.gob.ec/magap-socializa-acuerdo-394-sobre-la-calidad-y-normativa-de-la-leche/ (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Revelli, G.; Sbodio, O.; Tercero, E. Estudio y Evolución de La Calidad de Leche Cruda En Tambos de La Zona Noroeste de Santa Fe y Sur de Santiago Del Estero, Argentina (1993–2009). RIA 2011, 37, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- INEC-ESPAC. Encuesta de Superficie y Producción Agropecuaria Continua ESPAC. 2021. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_agropecuarias/espac/espac-2021/Principalesresultados-ESPAC_2021.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- CIL. El Sector Lácteo Ecuatoriano se Reactiva con Miras Positivas para el 2022. 2021. Available online: https://www.cil-ecuador.org/post/el-sector-l%C3%A1cteo-ecuatoriano-se-reactiva-con-miras-positivas-para-el-2022 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Contero, R.; Aquino, E.L.; Simbaña, P.E.; Gallardo, C.; Bueno, R. A Study in Ecuador of the Calibration Curve for Total Bacterial Count by Flow Cytometry of Raw Bovine Milk. Granja 2019, 29, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terán, J. Análisis del Mercado de la Leche en Ecuador: Factores Determinantes y Desafíos. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2019. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/124490 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- De la Cueva, F.; Naranjo, A.; Puga Torres, B.H.; Aragón, E. Presencia de Metales Pesados En Leche Cruda Bovina de Machachi, Ecuador. Granja 2021, 33, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balseca, P.; Mosquera, J. Determinación Cuantitativa de Residuos En Leche de Eprinomectina Usado Como Mosquicida En Vacas Lecheras. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chuquín, H.; Aquino, E.; De la Cruz, E. Diagnóstico Del Manejo de La Calidad de Leche y Del Queso En La Provincia Del Carchi. SATHIRI 2016, 11, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, A.; Mancebo, B.; Sánchez, L.; Chiriboga, X.; Lucero, D.; Marrero, E.; Silva, J. Residualidad Del Ptaquilósido En La Leche Procedente de Granjas Bovinas En Tres Cantones de La Provincia Bolívar, Ecuador. Rev. Salud Anim. 2014, 36, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia, D.; Simbaina, J. Evaluation of the Quality of Bovine Milk of the Livestock Farms of Suscal, Cañar, Ecuador. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2019, 7, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, N.; Díaz, J.; Hernández, A. Evaluación de La Eficiencia Tecnológica En La Elaboración Artesanal de Queso Fresco de Coagulación Enzimática. Tecnol. Química 2017, 3, 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, E.; García, R.; Montesdeoca, R.; Buste, M.; López, G. Diagnóstico de La Calidad Higiénico Sanitaria de La Leche de Los Sistemas Bovinos Del Cantón El Carmen. Rev. Ecuat. Cienc. Anim. 2022, 4, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, C.; Díaz, R.; Morales, W.; Godoy, V.; Calderón, N.; Cegido, J. Calidad Físico-Química e Higiénico Sanitaria de La Leche En Sistemas de Producción Doble Propósito, Manabí-Ecuador. Rev. Investig. Talent. 2018, 5, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, J.; Peñafiel, J. Determinaciónde La Incidencia de Mastitis Subclínica Mediante Los Métodos California Mastitis Test (CMT) y Somaticell En Cinco Ganaderías Del Cantón Vinces Provincia de Los Ríos. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Católica Santiago de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2011. Available online: http://repositorio.ucsg.edu.ec/handle/3317/993 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Salguero, A.; Puga, B. Calidad de Leche Cruda de Pequeños Productores Del Cantón Cayambe y Pedro Moncayo, Por Análisis Físico Químicos y Ensayos Cualitativos. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/handle/25000/20256 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Rosero, D.; Chiriboga, X. Xtracción, Identificación, Cuantificación de Ptaquilósido En Leche de Ganado Vacuno Que Pastorea En Zonas Donde Crece Pteridium Arachnoideum. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/handle/25000/1903 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Guevara-Freire, D.; Montero-Recalde, M.; Valle, L.; Avilés-Esquivel, D. Calidad de Leche Acopiada de Pequeñas Ganaderías de Cotopaxi, Ecuador. Rev. Investig. Vet. Perú 2019, 30, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.; Pincay, P. Evaluación de la Calidad Fisicoquímica y Microbiológica de la Leche Cruda Obtenida de Dos Haciendas Ubicadas en el Cantón Bucay Provincia Del Guayas. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Católica Santiago de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2016. Available online: http://repositorio.ucsg.edu.ec/handle/3317/6933 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Sánchez, C.; Rojas, J. Estudio Preliminar de Aerobios Mesófilos en la Leche Cruda Que Se Expende En Carros Repartidores En la Ciudad de Cuenca. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: http://dspace.uazuay.edu.ec/handle/datos/3206 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Rodríguez, A.; Montero, M. Determinación De La Inocuidad Y Calidad Fisicoquímica De Leche Cruda En Plantas Procesadoras Del Cantón Salcedo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ambato, Ecuador, 2016. Available online: https://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/jspui/handle/123456789/24354 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Rivera, N.; Rodríguez, S.; Pérez, C. Diagnóstico de Situación Del Proceso Productivo y Evaluación de La Calidad de La Leche En La Asociación Agropecuaria “El Trébol”. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/bitstream/25000/18314/1/T-UCE-0014-MVE-044.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Mosquera, J.; León, P. Diseño de Un Sistema de Buenas Prácticas de Ordeño Basado En La Resolución MAGAP-Agrocalidad N° 0217 Para La Hacienda San José Del Belén En El Sector de Tambillo. Master’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.puce.edu.ec/bitstream/handle/22000/17301/proyectoXavierMosqueraf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Velastegui, C.; Proaño, D. Evaluación Del Sistema de Gestión de Calidad de La Leche En Unidades Productivas y Centros de Acopio Del Cantón Quito. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Neppas, E.; Requelme, N. Sistematización y Análisis Del Proceso de Gestión de La Calidad de La Leche Del Centro de Acopio “El Progreso” de Cariacu, Cantón Cayambe. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2014. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/7514 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Ortíz, M.; Rosales, C.; Aguilar, Y.; Murillo, Y.; Serpa, G.; Paguay, T.; Coronel, Á. Estudio Exploratorio Sobre La Presencia de Contaminantes En leche cruda proveniente de la cuenca lechera del Tarqui de la sierra sur ecuatoriana. MASKANA 2017, 8, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paguay, T.; Coronel, A.; Ortíz, M. Determinación de La Incidencia de Adulterantes e Inhibidores de Leche Cruda Almacenada En Diez Centros de Acopio de La Provincia Del Azuay. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/23504 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Peña, F.; Cuarán, M. Diseño de Un Manual de Buenas Prácticas de Manufactura Para Centros de Acopio de Leche Cruda. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.utn.edu.ec/handle/123456789/9775 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Contero Callay, R.E.; Requelme, N.; Cachipuendo, C.; Acurio, D. Calidad de La Leche Cruda y Sistema de Pago Por Calidad En El Ecuador. Granja 2021, 33, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; País, J. Evaluación de La Calidad Higiénica Sanitaria de Leche Cruda Mediante La Prueba de Lactofermentación a Nivel de Centros de Acopio En La Provincia Del Carchi. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.utn.edu.ec/handle/123456789/8828 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Pilamunga, C.; Albuja, A. Evaluación Higiénico–Sanitaria De La Quesera Artesanal Cod.Q 1 Ubicada En La Parroquia Químiag Del Cantón Riobamba, Provincia De Chimborazo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/handle/123456789/6937 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Ortíz, M.C.M. Determinación de La Presencia de Aflatoxina M1 y Antibióticos En Leche Cruda de Las Fincas de Mayor Producción Del Cantón Biblán. Master’s Thesis, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2014. Available online: http://dspace.uazuay.edu.ec/bitstream/datos/3341/1/10109.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Villegas, Z.; Freire, J.L.; Yépez, L. Evaluación de La Calidad Físico Química y Microbiológica de La Leche Cruda Que Se Expende En El Cantón Bolívar Provincia Del Carchi. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador, 2011. Available online: http://repositorio.utn.edu.ec/handle/123456789/386 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Valle, T.; Díaz, B. Evaluación De La Calidad De La Leche Cruda E Implementación De Un Manual De Calidad En El Centro De Acopio: Asociación El Panecillo, Tungurahua. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/4621/1/56T00600UDCTFC.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- González, P.; Ortíz, J. Determinación de Aflatoxina M1 en Leche Cruda de Vaca en Centros de Acopio de Pequeños Productores en las Cinco Provincias de la Sierra con Mayor Producción en el Ecuador. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de las Américas, Quito, Ecuador, 2018. Available online: http://dspace.udla.edu.ec/handle/33000/9836 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Castro, M.; Suárez, C. Determinación de La Presencia de Antibiótico En Leche Cruda de Bovino Comercializada Directamente En La Viviendas de Las Parroquias de Victoria Del Portete y Tarqui. Master’s Thesis, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: http://dspace.uazuay.edu.ec/bitstream/datos/6672/1/12688.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Chacón, F.; Sagday, C. Evaluación de Los Análisis Físicos-Químicos de La Leche Bovina. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/13538/1/UPS-CT006912.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Castillo, P.; Ortega, R.; Vaca, C. Determinación de La Alteración-Adulteración de Leche Cruda Mediante Análisis Físico- Químicos En Medios de Transporte Legalizados, Provenientes de La Parroquia Tarqui, Cantón Cuenca. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2016. Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/jspui/bitstream/123456789/23505/1/TesisCastillo%2COrtega.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Carrera, M.; León, G.; Rosales, M. Mejoramiento de La Calidad de La Leche de Pequeños Productores Del Cantón Biblian. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuadro, 2018. Available online: http://dspace.uazuay.edu.ec/handle/datos/7817 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Puga-Torres, B.; Cáceres-Chicó, M.; Alarcón-Vásconez, D.; Gómez, C. Determination of Zearalenone in Raw Milk from Different Provinces of Ecuador. Vet. World 2021, 14, 2048–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco, F. Gestión de Riesgo Por Presencia de Residuos de Antibióticos En Leche Cruda. Master’s Thesis, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: http://dspace.uazuay.edu.ec/bitstream/datos/7845/1/13639.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Cárdenas, C.; Murillo, M.; Murillo, Y. Calidad Bacteriológica de La Leche Cruda En Ganaderías de La Provincia Del Azuay. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2018. Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/31455 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Torres, M.; Díaz, M. Determinación de Niveles de Tetraciclina y Oxitetraciclina En Leche Cruda En La Asociación Copla (Corporación Productora de Leche de Alóag) de La Parroquia Alóag Del Cantón Mejía. Master’s Thesis, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/bitstream/25000/6427/1/T-UCE-0008-106.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Caracundo, E.; Garnica, F. Determinación Antibióticos Betalactámicos y Tetraciclinas En La Leche Cruda Comercializada. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/17391/1/UPS-CT008305.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Aroca, N.; Álvarez, C. Detección Cualitativa de Residuos de Antibióticos En Leche Cruda Comercializada En El Cantón Naranjal Provincia Del Guayas. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica de Machala, Machala, Ecuador, 2016. Available online: http://repositorio.utmachala.edu.ec/handle/48000/7695 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Chanaluisa, J.; Quishpe, X. Estandarización de La Rutina de Ordeño de Bovinos En Las Unidades Productivas Del Cantón Salcedo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica de Cotopaxi, Latacunga, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.utc.edu.ec/bitstream/27000/6065/6/PC-000523.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Buñay, N.; Peralta, F.; León, J. Determinación Del Recuento de Aerobios Mesófilos En Leche Cruda Que Ingresa a Industrias Lacto Ochoa-Fernández Cia. Ltda. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/21584 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Cabezas, L.; Cuaran, J. Influencia de Las Prácticas de Ordeño Sobre La Calidad de Leche de Fincas Ganaderas de La Provincia de Pichincha. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador, 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.utn.edu.ec/handle/123456789/9778 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Calderón, P.; Morales, W. Calidad Microbiologica de La Leche de Bovinos de Doble Propósito Bajo Dos Sistemas de Ordeño En Cuatro Cantones de Manabí. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad técnica Estatal de Quevedo, Quevedo, Ecuador, 2016. Available online: https://repositorio.uteq.edu.ec/handle/43000/2038 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Calderón, N.; Morales, W. Cromatografía de AGV y Células Somáticas Como Indicadores de La Calidad de Leche, Bajo Dos Sistemas de Ordeño. Manabí-Ecuador. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica Estatal de Quevedo, Quevedo, Ecuador, 2016. Available online: https://repositorio.uteq.edu.ec/handle/43000/2037 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Almeida, D.; Bonifaz, N. Prevalencia de Mastitis Bovina Mediante La Prueba de California Mastitis Test e Identificación Del Agente Etiológico, En El Centro de Acopio de Leche En La Comunidad San Pablo Urco, Olmedo-Cayambe-Ecuador, 2014. Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, 2015. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/9834 (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Vallejo, J.; Ramón, E. Influencia Del Ordeño En El Recuento de Células Somáticas Sobre La Calidad Del Queso Andino En La Organización Inti Churi”. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica Estatal de Quevedo, Quevedo, Ecuador, 2020. Available online: http://dspace.ueb.edu.ec/handle/123456789/3629 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Chasi, E.; Bonifaz, N. Prevalencia de Mastitis Bovina Mediante La Prueba de California Mastitis Test e Identificación Del Agente Etiológico, En El Centro de Acopio de Leche En La Comunidad de Muyurco, Cayambe-Ecuador, 2014. 2015. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/9839 (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Chicaiza, J.; Godoy, V. La Calidad de La Leche Después Del Ordeño En Diferentes Fincas Del Centro Sur Del Cantón La Maná. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica Estatal de Quevedo, Quevedo, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: https://repositorio.uteq.edu.ec/handle/43000/4439 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Chuquimarca, A.; Vayas, E. Implementación y Evaluación de Buenas Prácticas de Manufactura (BPM) y Principios Estándares de Sanítización (SOPS) En La Asociación de Queseros de Guamote, Para La Producción de Queso Fresco. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2010. Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/handle/123456789/2268 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Defaz, E.; Pérez, O.; Pérez, D. Determinación De La Calidad Físico-Química Y Microbiológica De La Leche Cruda De Los Centros De Acopio De Las 10 Asociaciones Del Conlac-T. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/bitstream/25000/4251/1/T-UCE-0014-60.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Duy, J.; Garnica, F. Determinación de Antibióticos Betalactámicos, Tetraciclinas y Sulfonamidas En La Leche Cruda de Pequeños Productores. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2020. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/19195/1/UPS-CT008828.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Erazo, W.; Andrade, D. Estudio Comparativo de La Calidad de La Leche Cruda Bovina Producida En Dos Cantones de La Provincia de Napo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de las Américas UDLA, Quito, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: http://dspace.udla.edu.ec/handle/33000/8164 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Espinosa, J.; Castro, B. Evaluación Mediante Citometría De Flujo De La Calidad De Leche De Los Bovinos (Bos Taurus) De Las Provincias De Pichincha Y Cotopaxi En Las Muestras Tomadas Por Pasteurizadora Quito En El Periodo Noviembre 2016-Enero 2017. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: http://repositorio.ug.edu.ec/bitstream/redug/24825/1/T-UG-POS-DP-MBM--MBM-00048.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Espinoza, M.; Mier, J.; Mosquera, J. Determinación de La Prevalencia de Mastitis Mediante La Prueba California Mastitis Test e Identificación y Antibiograma Del Agente Causal En Ganaderías Lecheras Del Cantón El Chaco, Provincia Del Napo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/handle/25000/1281#:~:text=Mediante%20la%20prueba%20de%20California,microorganismos%20aislados%20fueron%3A%20Staphylococcus%20spp (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Fienco, D.; Diaz, M. Evaluación Del Proceso Sanitario Del Ordeño y Control de Calidad de La Leche Cruda Procedente de Los Centros de Acopio de Las Parroquias El Chaupi y El Pedregal Pertenecientes Al Cantón Mejía Que Proveen a La Empresa El Ordeño. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/handle/25000/4363 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Farinango, A.; Bonifaz, N. Prevalencia de Mastitis Bovina Mediante La Prueba de California Mastitis Test e Identificación Del Agente Etiológico, En El Centro de Acopio de Leche En La Comunidad de Pulisa, Cayambe-Ecuador, 2014. Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, 2015. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/9826 (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Fonseca, L.; Bonifaz, N. Prevalencia de Mastitis Bovina Mediante La Prueba de California Mastitis Test Con Identificación Del Agente Etiológico Del Agente Etiológico, En El Centro de Acopio de Leche Ce La Comunidad El Chaupi, Cayambe–Ecuador, 2014. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/9825%0A (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Gonzalez, M.; Bonifaz, N. Estudio Del Punto Crioscópico de Leche Cruda Bovina, En Dos Pisos Altitudinales y Dos Épocas Del Año, Ecuador 2012. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/6050/1/UPS-YT00269.pdf%0A (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Calderón, A.; Mancebo, B.; Sánchez, L.; Chiriboga, X.; Lucero, D.; Marrero, E. Niveles de Ptaquilósido En Muestras de Leche Bovina En Granjas de San Miguel de Bolívar, Provincia Bolívar, Ecuador. Rev. Salud Anim. 2013, 35, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Guartatanga, J.; Barragán, S. Diagnóstico de Mastitis Subclínica Mediante La Prueba de California Mastitis Test, y Recuento de Mesófilos (Ufc) En Ganaderías de La Parroquia Pachicutza Del Cantón El Pangui. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Loja, Loja, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: https://dspace.unl.edu.ec/jspui/handle/123456789/18823?mode=full%0A (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Jiménez, D.; Bahamonte, R. Estudio de La Adulteración de Leche Cruda Con Suero de Quesería, Mediante Cromatografía Líquida de Ultra Eficiencia (Uplc). Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://www.dspace.uce.edu.ec/handle/25000/6418 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Lagla, M.; Albuja, A. Evaluación Higiénico-Sanitaria De La Quesera Artesanal Cod.Q 7 Ubicada En El Cantón Mocha, Provincia Tungurahua. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2018. Available online: http://dspace.espoch.edu.ec/handle/123456789/9022 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Verdesoto, V.; Carrasco, W. El Ordeño Manual En Bovinos de Leche y Su Incidencia En La Contaminación Microbiana En La Parroquia Quinchicoto, Cantón Tisaleo-Tungurahua. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Estatal de Bolívar, Guanujo, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: https://rraae.cedia.edu.ec/Record/UEB_5500883c77e38a9aff8ee5069ac02cfb (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Malla, A.; Saula, S.; Uguña, M. Determinación Del Metabolito Tóxico Aflatoxina M1 En Leches Cruda, Pasteurizada y Ultrapasteurizada Consumidas En La Ciudad de Cuenca Mediante La Técnica de Cromatografía Líquida de Alta Resolución (HPLC). Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/23399 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Monge, R.; Cuarán, M. Diseño de Un Centro de Acopio Modelo Para Leche Cruda. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: http://repositorio.utn.edu.ec/handle/123456789/7773 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Martínez-Villarreal, D.; Morales, S.; Núñez, L.; Santander, S.; De la Cueva, F.; Puga-Torres, B. Determination of the Hygienic and Physico-Chemical Quality of Raw Milk Produced by Small and Medium Producers of the North-East Region of Carchi-Ecuador. Asian J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 5908–5913. [Google Scholar]

- Albán, D.; Bonifaz, N. Identificación de Los Puntos Críticos En Sistemas de Producción Que Influyen En El Conteo de Células Somáticas de Leche Cruda y En El Rendimiento de Queso Mozzarella, Ecuador 2012. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/handle/123456789/6048 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Marañón, J.; Reina, J. Parámetros de Calidad En Leche Cruda Según La Norma NTE INEN 9:2012 En Centros de Acopio de La Provincia de Santo Domingo de Los Tsáchilas. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE, Sangolquí, Ecuador, 2017. Available online: http://repositorio.espe.edu.ec/xmlui/handle/21000/12959 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Mera, P. Evaluación De La Calidad De La Leche Mediante Citometría De Flujo, Proveniente De Bovinos De La Parroquia Machachi, Provincia De Pichincha. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE, Sangolquí, Ecuador, 2013. Available online: http://repositorio.espe.edu.ec/xmlui/handle/21000/7465 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Puga-Torres, B.; Salazar, D.; Cachiguango, M.; Cisneros, G.; Gómez-Bravo, C. Determination of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk from Different Provinces of Ecuador. Toxins 2020, 12, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, O.; Ayala, L.; Nieto, P.; Pesántez, J.; Rodas, E.; Vázquez, J.; Murillo, Y.; Aguilar, Y.; Serpa, V.; Dután, J.; et al. Determinación de Adulterantes En Leche Cruda de Vaca En Centros de Acopio, Medios de Transporte y Ganaderías de La Provincia Del Cañar, Ecuador. Maskana 2017, 8, 133–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, J.; Romero, H. Presencia de Metales Pesados (Arsénico y Mercurio) En Leche de Vaca Al Sur de Ecuador. Granja. Rev. Cienc. La Vida 2013, 17, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEN. Leche Cruda: Requisitos NTE INEN 9. Available online: https://www.gob.ec/sites/default/files/regulations/2018-10/Documento_BLNTEINEN9LechecrudaRequisitos.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Akgönüllü, S.; Yavuz, H.; Denizli, A. Development of Gold Nanoparticles Decorated Molecularly Imprinted–Based Plasmonic Sensor for the Detection of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk Samples. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC. Some Traditional Herbal Medicines, Some Mycotoxins, Naphthalene and Styrene. Available online: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Monographs-On-The-Identification-Of-Carcinogenic-Hazards-To-Humans/Some-Traditional-Herbal-Medicines-Some-Mycotoxins-Naphthalene-And-Styrene-2002 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- López, A. Manual de Industrias Lácteas, 1st ed.; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2003; ISBN 84-89922-81-0. Available online: https://books.google.com.ec/books?id=xcaN14spLCcC&printsec=frontcover&d=&hl=es-419 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Barrera-Forero, J.M. Evaluación de La Calidad Fisico-Quimica de La Leche Cruda Que Se Expende En Tunja (Boyacá), Universidad de Tunja. Bachelor’s Thesis, Fundación Universitaria Juan de Castellanos, Boyacá, Columbia, 2013. Available online: https://issuu.com/ingenieriaagropecuariajdc/docs/evaluaci__n_de_la_calidad_fisicoqu_ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Singuluri, H.; Sukumaran, M. Milk Adulteration in Hyderabad, India—A Comparative Study on the Levels of Different Adulterants Present in Milk. J. Chromatogr. Sep. Tech. 2014, 5, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIL. La Leche Del Ecuador-Historia de La Lechería Ecuatoriana, 1st ed.; CIL: Quito, Ecuador, 2015; Available online: http://www.pichincha.gob.ec/publicaciones/item/702-la-leche-del-ecuador.html (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Briñez, W.J.; Valbuena, E.; Castro, G.; Tovar, A.; Ruiz-Ramírez, J. Algunos Parámetros de Composición y Calidad En Leche Cruda de Vacas Doble Propósito En El Municipio Machiques de Perijá, Venezuela. Red Rev. Científicas América Lat. Caribe España Port. 2008, 18, 607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara, M. Evaluación Físico- Química e Higiénica de La Producción de Leche Fresca En El Distrito de Sócota, Cutervo, Cajamarca, 2015. Sagasteguiana 2015, 2, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, J.; Sanchez, J.; Stryhn, H.; Ortiz, T.; Olivera, M.; Keefe, G.P. Influence of Milking Method, Disinfection and Herd Management Practices on Bulk Tank Milk Somatic Cell Counts in Tropical Dairy Herds in Colombia. Vet. J. 2017, 220, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietoris, V.; Zajac, P.; Zubrická, S.; Čapla, J.; Čurlej, J. Comparison of Total Bacterial Count (TBC) in Bulk Tank Raw Cow’s Milk and Vending Machine Milk. Carpathian J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 8, 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, N.; Hill, C.; Ross, P.R.; Beresford, T.P.; Fenelon, M.A.; Cotter, P.D. The Prevalence and Control of Bacillus and Related Spore-Forming Bacteria in the Dairy Industry. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimlich, W.; Carrillo, B. Manual Para Centros de Acopio de Leche. Producción, Operación, Aseguramiento de Calidad y Gestión; Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (CORFO): Santiago, Chile; Egall-Master Print Ltda: Santiago, Chile, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Naing, Y.W.; Wai, S.S.; Lin, T.N.; Thu, W.P.; Htun, L.L.; Bawm, S.; Myaing, T.T. Bacterial Content and Associated Risk Factors Influencing the Quality of Bulk Tank Milk Collected from Dairy Cattle Farms in Mandalay Region. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chala, A.; Mitiku, E. Hygienic Practice, Microbial Quality and Physco-Chemical Properties of Milk Collected from Farmers and Market Chains in Eastern Wollega Zone of Sibu Sire Districts, Ethiopia. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Food Technol. 2021, 7, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, L.E.; Brett, J.; Kelton, D.; Majowicz, S.E.; Snedeker, K.; Sargeant, J.M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Pasteurization on Milk Vitamins, and Evidence for Raw Milk Consumption and Other Health-Related Outcomes. J. Food Prot. 2011, 74, 1814–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gecaj, R.M.; Ajazi, F.C.; Bytyqi, H.; Mehmedi, B.; Çadraku, H.; Ismaili, M. Somatic Cell Number, Physicochemical, and Microbiological Parameters of Raw Milk of Goats During the End of Lactation as Compared by Breeds and Number of Lactations. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 694114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Gámez, H.; Muñoz-Domínguez, L.; Quitiaquez-Montenegro, D.; Fajardo-Argoti, C.; Insuasty-Santácruz, E. Evaluación de La Calidad Composicional, Microbiológica y Sanitaria de La Leche Cruda En El Segundo Tercio de Lactancia En Vacas Lecheras. Rev. La Fac. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2019, 66, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Reyes, J.; Bedolla Cedeño, J. Importancia Del Conteo de Células Somáticas En La Calidad de La Leche REDVET. Rev. Electrónica Vet. 2008, 9, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.N.; Wang, J.Q.; Li, S.L.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zheng, N. Aflatoxin M1 Cytotoxicity against Human Intestinal Caco-2 Cells Is Enhanced in the Presence of Other Mycotoxins. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 96, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz, A.; Cabral Silva, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Venâncio, A. Detection Methods for Aflatoxin M1 in Dairy Products. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, F.; Darsanaki, R.K.; Mohammadi, M.; Kolavani, M.H.; Issazadeh, K.; Aliabadi, M.A.; Branch, L. Determination of Aflatoxin M1 Levels in Raw Milk Samples in Gilan, Iran. Adv. Stud. Biol. 2013, 5, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bilandžić, N.; Kolanović, B.S.; Varenina, I.; Scortichini, G.; Annunziata, L.; Brstilo, M.; Rudan, N. Veterinary Drug Residues Determination in Raw Milk in Croatia. Food Control 2011, 22, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Leung, D.; Lenz, S.P. Determination of Five Macrolide Antibiotic Residues in Raw Milk Using Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2873–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Wang, J.; Han, R.; Xu, X.; Zhen, Y.; Qu, X.; Sun, P.; Li, S.; Yu, Z. Occurrence of Several Main Antibiotic Residues in Raw Milk in 10 Provinces of China. Food Addit. Contam. Part B Surveill. 2013, 6, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, F.; Jank, L.; Castilhos, T.; Rau, R.B.; Tomaszewski, C.A.; Ribeiro, C.; Hillesheim, D.R. Chemical Residues and Mycotoxins in Raw Milk; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, A.G.; Csabai, I.; Krikó, E.; Tőzsér, D.; Maróti, G.; Patai, Á.V.; Makrai, L.; Szita, G.; Solymosi, N. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Raw Milk for Human Consumption. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón, A. Comparación de La Titulación de La Acidez de Leche Caprina y Bovina Con Hidróxido de Sodio y Cal Común Saturada. Agron. Mesoam. 2006, 17, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sowmya, R.; Indumathi, K.P.; Arora, S.; Sharma, V.; Singh, A.K. Detection of Calcium Based Neutralizers in Milk and Milk Products by AAS. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Campos-Vallejo, M.; Puga-Torres, B.; Núñez-Naranjo, L.; Torre-Duque, D.D.L.; Morales-Arciniega, S.; Vayas, E. Evaluation of the Use of Sodium Thiocyanate and Sodium Percarbonate in the Activation of the Lactoperoxidase System in the Conservation of Raw Milk without Refrigeration in the Ecuadorian Tropics. Food Nutr. Sci. 2017, 8, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranha, P.C. dos R.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Wolf-Jäckel, G.A.; Jensen, H.M.E.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Friis, C. Fate of Ptaquiloside—A Bracken Fern Toxin—In Cattle. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudebbouz, A.; Boudalia, S.; Bousbia, A.; Habila, S.; Boussadia, M.I.; Gueroui, Y. Heavy Metals Levels in Raw Cow Milk and Health Risk Assessment across the Globe: A Systematic Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Liu, H.; Qu, X.; Zhou, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, H.; Zheng, N.; Wang, J. Heavy Metals in Raw Milk and Dietary Exposure Assessment in the Vicinity of Leather-Processing Plants. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 3303–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhanardakani, S. Human Health Risk Assessment of Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn through Consumption of Raw and Pasteurized Cow’s Milk. Iran J. Public Health 2018, 47, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).