Spatial–Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Economic Effects of China’s Cultural and Tourism Industries’ Collaborative Agglomeration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Indicators and Methods

2.1. Indicators

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Coupling Coordination Model

2.2.2. Spatial Correlation Test

- (1)

- GMI: In this study, we explored the overall correlation between the culture and tourism industries through GMI. Its mathematical expression can be given as:where is the global spatial autocorrelation index of the culture and tourism industries in a region ; represents the research sample of 31 provinces and cities in China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan); represents the standardization elements, and its value is the weight matrix element; and represent the observed values for regions and , respectively; is the average of the observations of variable ; and is the spatial weight matrix, which is used to represent the relationship between spatial data. When Moran’s I > 0, the spatial correlation is positive; that is, agglomeration exists in the spatial distribution of the culture and tourism industries. When Moran’s I < 0, the spatial correlation is negative; that is, a dispersion exists in the spatial distribution of the culture and tourism industries. When Moran’s I = 0, the variables are spatially independent; that is, no correlation exists in the spatial distribution of the cultural and tourism industries.

- (2)

- Local Moran’s I (LMI): We analyzed the local correlation between the culture and tourism industries through LMI. Its mathematical expression is:where is the local spatial autocorrelation index of the culture and tourism industries in region ; and represent the observed values in regions and , respectively; represents the variance of the observed value for region ; is the spatial weight matrix; and is the average of the observations of variable . The results of LMI are generally presented using the Moran scatter chart, which can be divided into four quadrants. These quadrants represent the four spatial association modes representing themselves and its adjacent spatial units. Among them, the first quadrant represents high–high agglomeration (H–H); that is, the observed values of itself and adjacent spatial units are high. The second quadrant is a low–high concentration (L–H), meaning that the low observation value area is surrounded by the high-observation-value areas. The third quadrant is low–low agglomeration (L–L), which means that the observed values of itself and its adjacent spatial units are low. The fourth quadrant is high–low agglomeration (H–L), which refers to a high-observation-value area surrounded by low-observation-value areas.

2.2.3. Spatial Vector Autoregressive Model

2.2.4. Impulse Response Function

3. Empirical Analysis

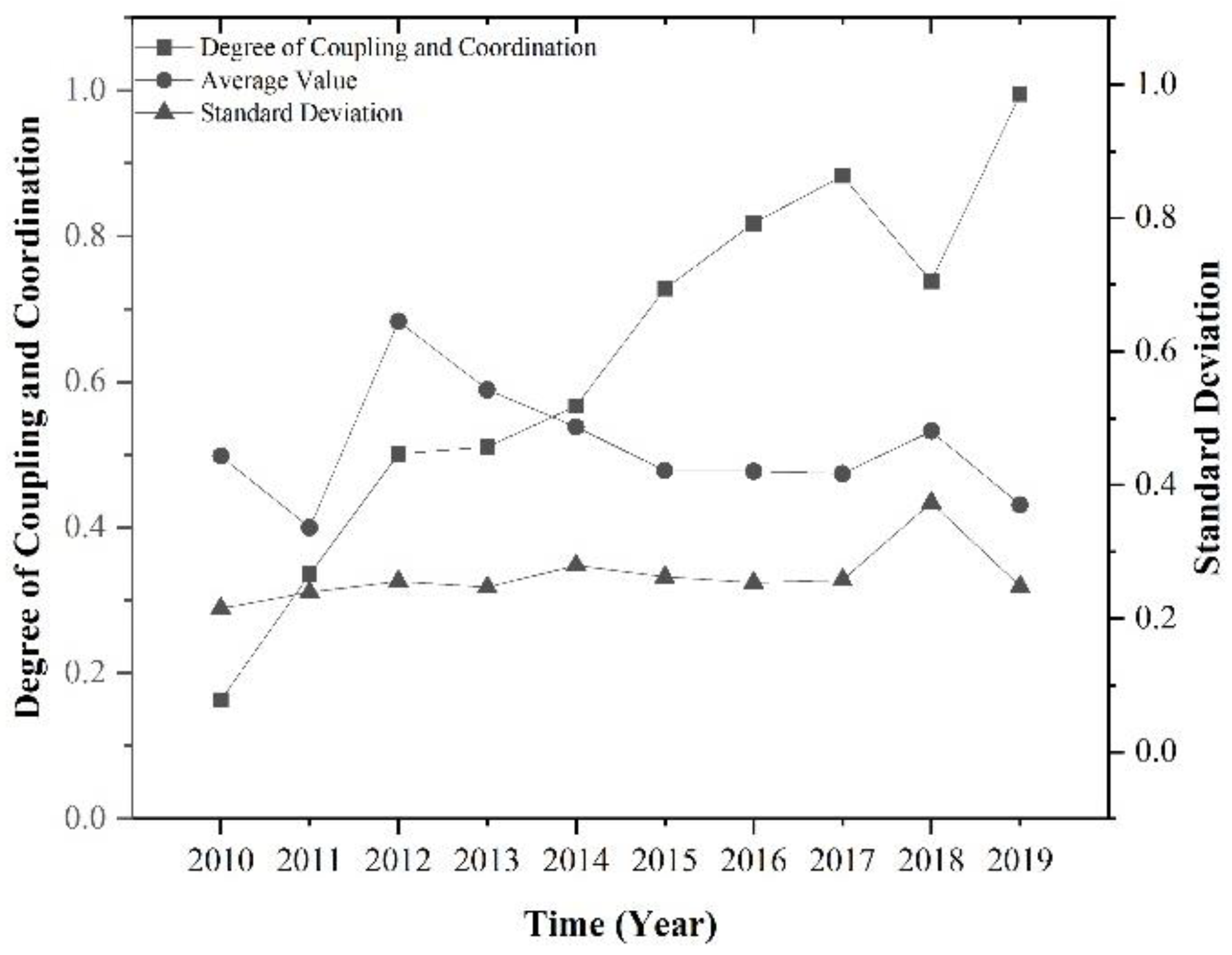

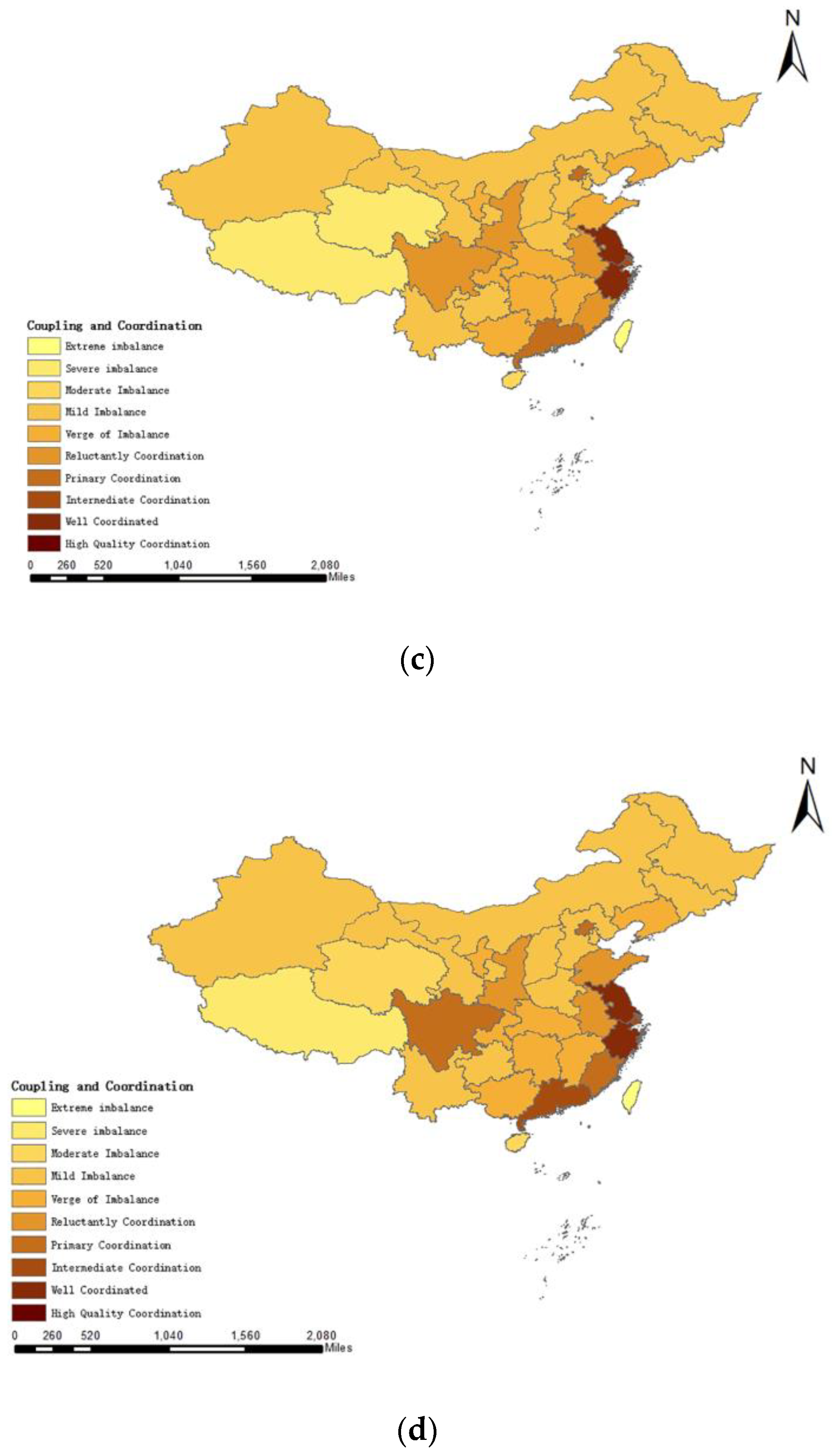

3.1. Coupling and Coordination Degree of Culture and Tourism Industries

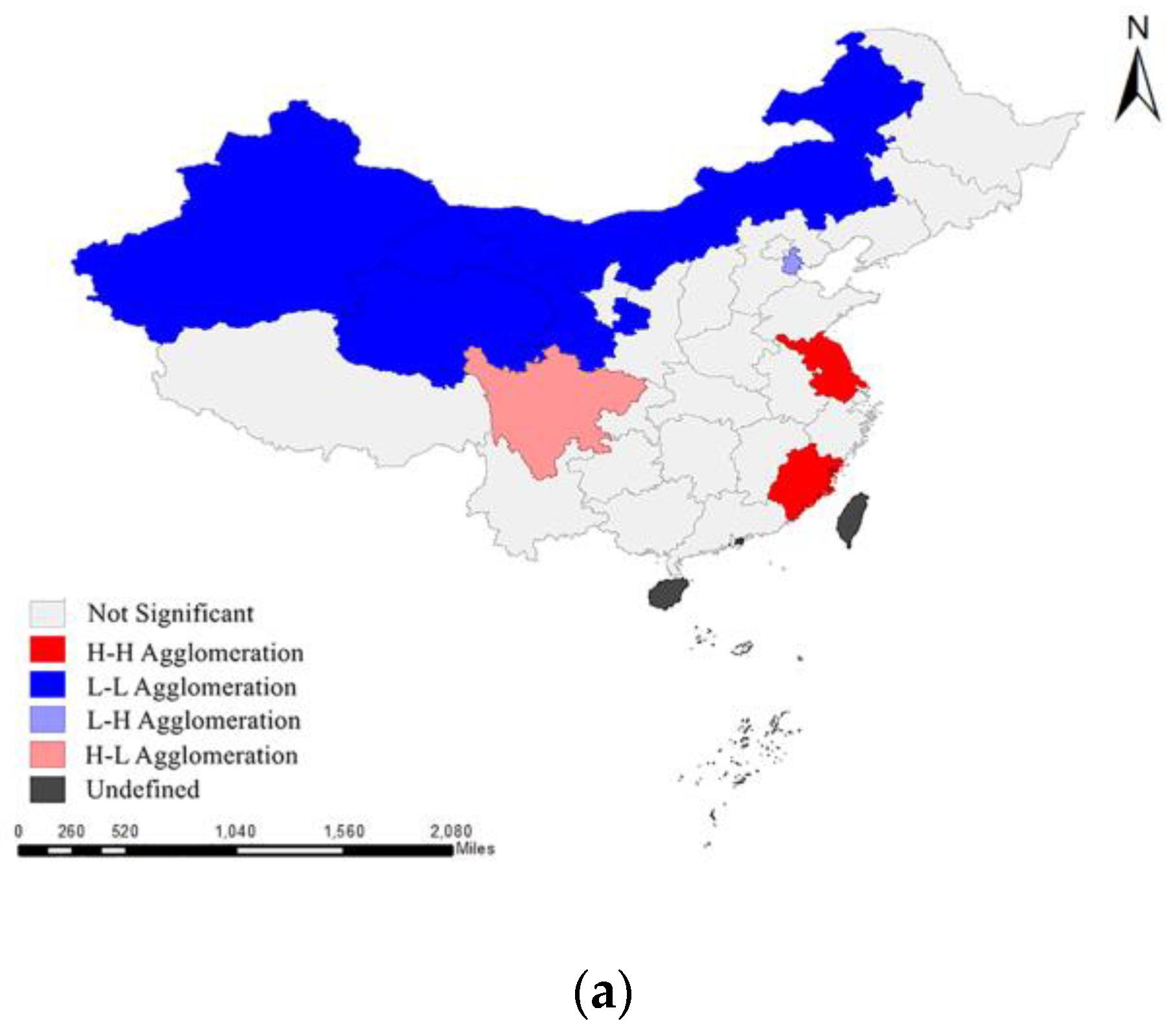

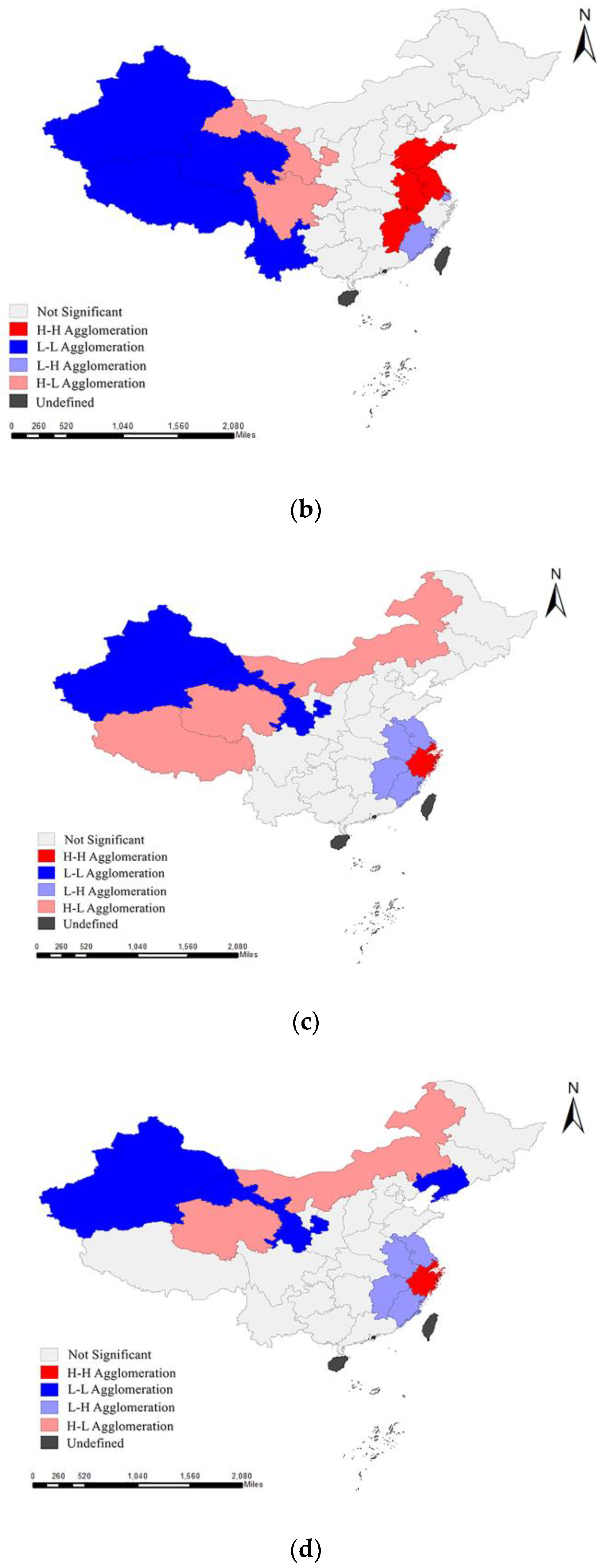

3.2. Spatial Correlation between Culture and Tourism Industries

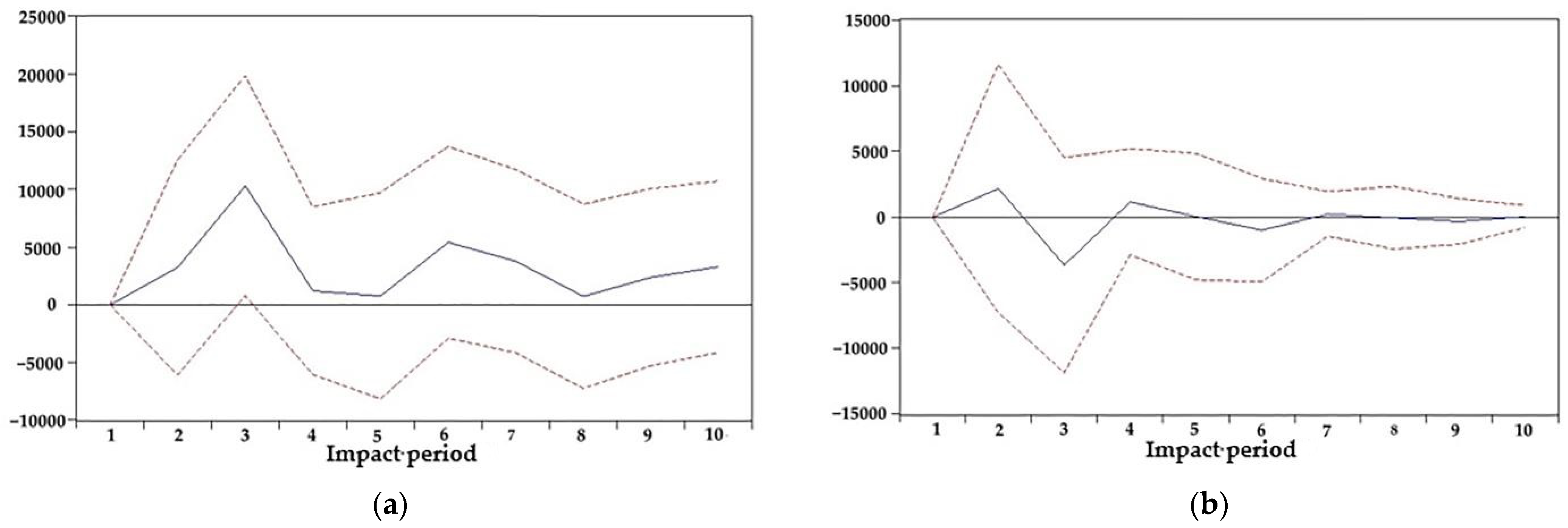

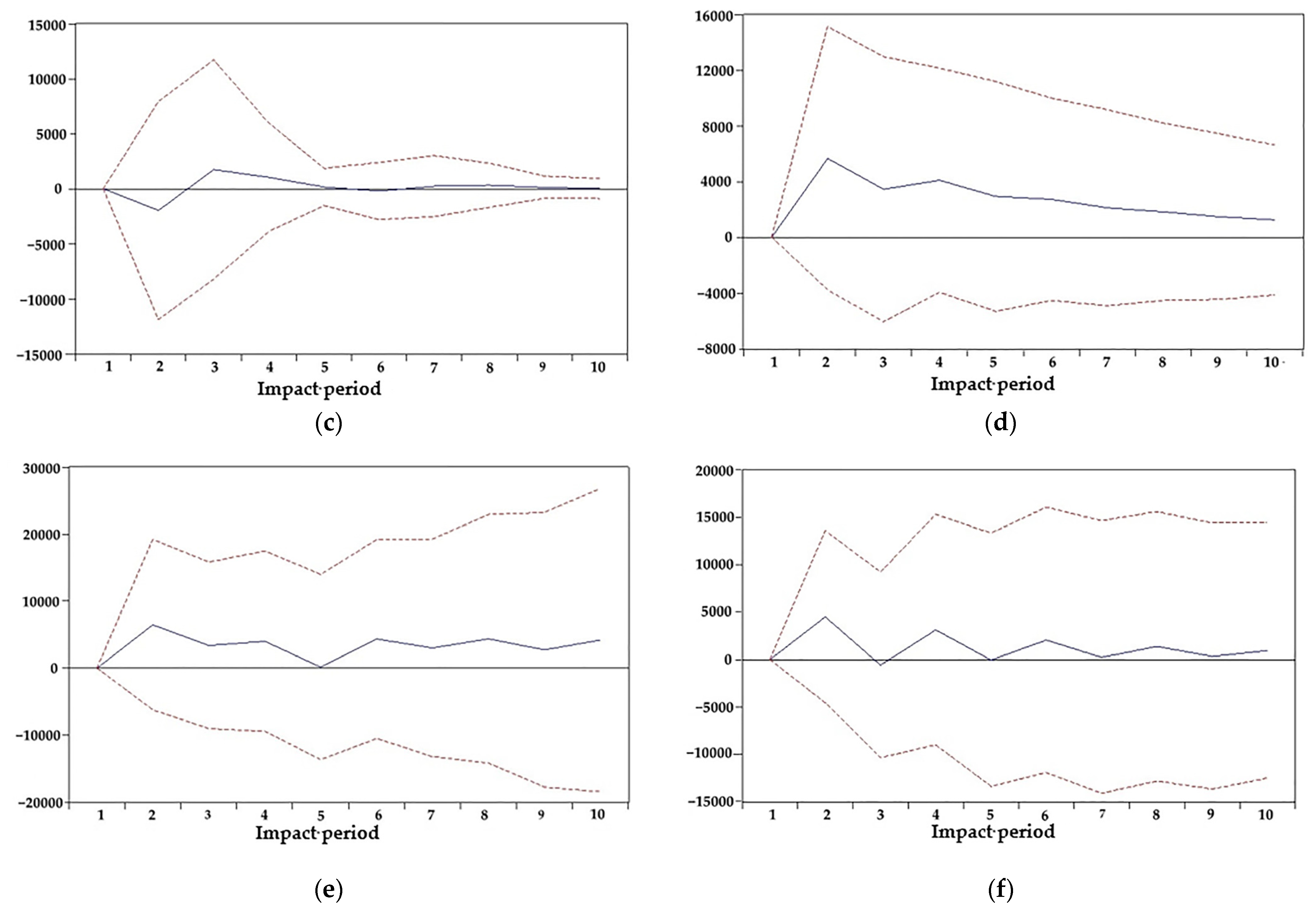

3.3. Economic Effect Test of Collaborative Agglomeration of Culture and Tourism Industries

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- From 2010 to 2019, there was a coupling and coordination relationship between the China’s culture and tourism industries in 31 provinces, and the collaborative agglomeration between the two was in the primary stage. Temporally, the degree of coupling and coordination between Chinese culture and tourism industries showed a tendency to increase in fluctuation—namely, from 2010 to 2017 when the degree of coupling and coordination between the two industries was on the rise. From 2017 to 2018, this degree of coupling and coordination decreased slightly, and from 2018 to 2019, it rose again. Spatially, the collaborative agglomeration development of the culture and tourism industries was stronger in the coastal areas than in the inland areas, and the level of coupling and coordination gradually decreased from the coastal to inland areas.

- (2)

- From 2010 to 2019, the overall spatial positive correlation between the Chinese cultural and tourism industries in 31 provinces was significant, while the local spatial correlation was different. In terms of the overall spatial correlation, the overall spatial positive correlation of Chinese cultural and tourism industries increased significantly from 2010 to 2014. From 2014 to 2018, the overall spatial positive correlation of the two industries showed a downward trend. However, the overall spatial positive correlation of the cultural and tourism industries increased again from 2018 to 2019. In terms of local spatial correlation, the provincial culture and tourism industries in Eastern China had a high degree of local spatial correlation, and the interregional industrial linkage effect was significant. The local spatial correlation between provincial culture and tourism industries in the central region was relatively low, and the interregional industrial linkage effect was general. The local spatial correlation between provincial culture and tourism industries in Western China was relatively high, and the effect of interregional industrial linkage was not significant.

- (3)

- The impact of the collaborative agglomeration of Chinese culture and tourism industries on the economy was nonlinear, and the impact of different industrial collaborative agglomeration factors on the Chinese economy was different. Six factors had a strong correlation with economic effects: (1) per capita cultural expenses, (2) domestic tourism revenue, (3) proportion of tourism revenue in the GDP, (4) per capita daily tourism foreign exchange revenue, (5) proportion of cultural establishments in financial expenditure, and (6) proportion of the added value of culture and related industries in the GDP. Among the factors, the four factors of per capita cultural expenses, domestic tourism revenue, proportion of tourism revenue in the GDP, and per capita daily tourism foreign exchange revenue had a positive impact on the economic effect, with the first two factors’ effects being more significant. The impact of the proportion of cultural establishments in financial expenditure on the economic effects fluctuated greatly in the early stage, but not significantly in the later stage. The impact of the proportion of the added value of culture and related industries in GDP on the economic effect showed a positive and negative fluctuation trend in the early stage, and the impact on the economic effect in the later stage was not significant.

5. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (1)

- Per Capita Cultural Expenses: Per capita expenditure of funds for cultural industry in various regions in China.

- (2)

- Proportion of Cultural Establishments in Financial Expenditure: Proportion of funds used for cultural industry in all regions in China in total regional financial funds.

- (3)

- Proportion of Added Value of Culture and Related Industries in GDP: The proportion of the output value created by the cultural industry and the related industrial production activities of all permanent residents in a region in a certain period of time of the regional GDP.

- (4)

- Number of Cultural Property Collections: Representative cultural relics with important historical, artistic, and scientific value.

- (5)

- Public Library Collections Per Capita: The number of books published in that year that can be owned by each person in the region within one year.

- (6)

- Number of Public Libraries: The total number of public cultural facilities open to the public free of charge in the region for collecting, sorting, and preserving literature information and providing inquiry, borrowing, and related services.

- (7)

- Number of Cultural Centers: The total number of institutions that provide free places for cultural activities to the public in the region.

- (8)

- Number of Museums: The total number of nonprofit institutions in the region that provide the public with access to historical and artistic relics.

- (9)

- Number of Art Performance Teams: The total number of all kinds of professional art performance groups that are sponsored by the regional cultural department or managed by the industry and specialized in performing arts and other activities.

- (10)

- Number of Employees in Public Libraries: The total number of people who work in public libraries and receive remuneration.

- (11)

- Number of Employees in the Cultural Centers: The total number of people who work in cultural centers and receive remuneration.

- (12)

- Number of Employees in Museums: The total number of people who work in museums and receive remuneration.

- (13)

- Number of Employees of Art Performance Groups: The total number of people who work in art performance groups and receive remuneration.

- (14)

- Number of Visitors to the Public Libraries: The total number of people who borrow and search for information in a public library in a unit of time.

- (15)

- Number of Visitors to the Cultural Centers: The total number of people who conduct cultural activities in a cultural center in a unit of time.

- (16)

- Number of Visitors to the Museums: The total number of visitors to the museum per unit time.

- (17)

- Number of Audience of Art Performance Groups: The total number of people who watch art performances per unit time.

- (18)

- Number of Domestic Tourists: The number of Chinese mainland residents and foreigners, and overseas Chinese and compatriots from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan who have resided in China for more than one year and stayed in tourist facilities in other places of China for at least one night and at most six months.

- (19)

- Number of Inbound Tourists: The number of foreigners, and overseas Chinese, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan compatriots who come to China to visit, travel, visit relatives, friends, recuperate, investigate, attend meetings, and engage in economic, scientific, technological, cultural, educational, religious and other activities. It does not include the staff of foreign permanent offices in China, such as embassies and consulates, news agencies, enterprise offices, or foreign experts, foreign students, and people who stay on shore for no more than one night.

- (20)

- Domestic Tourism Revenue: All the expenses that tourists spend on transportation, sightseeing, accommodation, catering, shopping, entertainment, etc., during their travel and sightseeing in China.

- (21)

- Proportion of Tourism Revenue in GDP: The proportion of tourists’ total expenses in the process of travel and sightseeing in various regions in China in the GDP.

- (22)

- Per Capita Daily Tourism Foreign Exchange Revenue: The average daily tourism income from each tourist in a tourist destination area.

- (23)

- Number of Scenic Spots: The total number of places with clear geographical boundaries and available for people to visit, stay, and rest.

- (24)

- Number of Starred Hotels: The total number of places providing accommodation, catering, and other services for tourists that meet the evaluation criteria of the China Tourism Administration.

- (25)

- Number of Travel Agencies: The total number of profit-making units that provide tourists with travel, residence, and related tourism services.

- (26)

- Number of Tourism Colleges and Universities: The total number of schools offering tourism-related majors such as tourism management and hotel management.

- (27)

- Number of Employees in Scenic Spots: The total number of people who work in scenic spots and receive remuneration.

- (28)

- Number of Employees in Starred Hotels: The total number of people who work in starred hotels and receive remuneration.

- (29)

- Number of Employees in Travel Agencies: The total number of people who work in travel agencies and receive remuneration.

- (30)

- Number of Students in Tourism Colleges: The total number of students studying tourism management, hotel management, and other tourism-related majors.

- (31)

- Operating Revenue of Scenic Spots: The total income of scenic spots from providing services or selling goods to consumers in the course of business activities.

- (32)

- Operating Revenue of Starred Hotels: The total income obtained by starred hotels through providing labor services, renting rooms, and catering.

- (33)

- Operating Revenue of Travel Agencies: The total income of travel agencies when providing various tourism services to tourists.

- (34)

- Total Number of People Received in Scenic Spots: The total number of people who visit and stay in scenic spots.

References

- Malmberg, A. Industrial geography: Agglomeration and local milieu. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Hu, M.; Su, B. Research on Investment Efficiency and Policy Recommendations for the Culture Industry of China Based on a Three-Stage DEA. Sustainability 2016, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filipova, M.K. Relationship between corporate culture and competitive power of the companies in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2015, 11, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.H.; Tsai, C.Y. Effects of Cultural and Tourist Connotations on the Overall Satisfaction of Tourists and Their Intentions to Revisit: A Case Study on Festival Tourism. J. Hum. 2016, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z. Research on the Integration and Development of Culture Industry and Tourism Industry of Fisherman Village in Rizhao. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coles, T.; Timothy, D.J. (Eds.) Tourism, Diasporas and Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H.L. Culture and tourism: A framework for further analysis. Manag. Leis. 2002, 7, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, K. Trinidad Carnival: Festival Tourism and Cultural Industry. Event Manag. 2004, 8, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R. Commodification, culture and tourism. Tour. Stud. 2016, 2, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joun, H.J.; Kim, H. Productivity Evaluation of Tourism and Culture for Sustainable Economic Development: Analyzing South Korea’s Metropolitan Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, G. A Study on the Integration of Culture Industry and Tourism Industry—A Case Study of Yancheng City in Jiangsu Province. Academics 2015, 4, 286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. Integrated Development of Marine Culture and Tourism Industry. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 112, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, H. Agglomeration Externalities and Skill Upgrading in Local Labor Markets: Evidence from Prefecture-Level Cities of China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Song, W.; Li, C. The Evolution of Industrial Agglomerations and Specialization in the Yangtze River Delta from 1990–2018: An Analysis Based on Firm-Level Big Data. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y. Agglomeration Production, Industry Association and Carbon Emission Performance: Based on Spatial Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Song, J.; Shen, Z. Does industrial agglomeration affect the regional environment? Evidence from Chinese cities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 7811–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S. Culture Industry Development and Regional Economy-Case Study of Tianjin. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.N.; Feng, J. Construction Model of Cultural System in Planning of Tourism Industry Zones-Based on the Planning and Practice of Beautiful Countryside construction under the Culture Resource of Yue Opera in Shengzhou. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech. 2017, 28, 2491–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Sotiriadis, M. Exploring and Evaluating the Impact of ICTs on Culture and Tourism Industries’ Convergence: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Pan, Y.; Gu, M. Cultural Tourism Resource Perceptions: Analyses Based on Tourists’ Online Travel Notes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cao, K. Spatial Analysis of Big Data Industrial Agglomeration and Development in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Meng, Q. Research on the Sustainable Synergetic Development of Chinese Urban Economies in the Context of a Study of Industrial Agglomeration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Zhang, P.; He, J. The Spatial Agglomeration and Industrial Network of Strategic Emerging Industries and Their Impact on Urban Growth in Mainland China. Complexity 2021, 2021, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Yang, X.; Wang, F. Urban Agglomeration Formation and Its Spatiotemporal Expansion Process in China: From the Perspective of Industrial Evolution. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, W.; Fang, C.; Song, J. Measurement and spatial distribution of urban agglomeration industrial compactness in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2008, 18, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duygu, S. Rethinking of Cities, Culture and Tourism within a Creative Perspective. Pasos Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2010, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.L.; Chen, F.W.; Liao, B. Foreign Trade, FDI and the Upgrading of Regional Industrial Structure in China: Based on Spatial Econometric Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 815–831. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Han, Q.; Tang, W. Exploration of the Industrial Spatial Linkages in Urban Agglomerations: A Case of Urban Agglomeration in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, Q.; Kim, D.J. An Empirical Study on Coupling Coordination between the Cultural Industry and Tourism Industry in Ethnic Minority Areas. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, D.; Chen, H.; Li, Y. Comprehensive Measurement, Spatiotemporal Evolution, and Spatial Correlation Analysis of High-Quality Development in the Manufacturing Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry Type | Primary Index | Secondary Index | Industry Type | Primary Index | Secondary Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Industry () | Basic Information | Per Capita Cultural Expenses () | Tourism Industry () | Basic Information | Number of Domestic Tourists () |

| Proportion of Cultural Establishments in Financial Expenditure () | Number of Inbound Tourists () | ||||

| Proportion of Added Value of Culture and Related Industries in GDP () | Domestic Tourism Revenue () | ||||

| Number of Cultural Property Collections () | Proportion of Tourism Revenue in GDP () | ||||

| Public Library Collections Per Capita () | Per Capita Daily Tourism Foreign Exchange Revenue () | ||||

| Cultural Organizations (Libraries, Cultural Centers, Museums, etc.) | Number of Public Libraries () | Event Venues (Hotels, Travel Agencies, and Tourism Institutions) | Number of Scenic Spots () | ||

| Number of Cultural Centers () | Number of Starred Hotels () | ||||

| Number of Museums () | Number of Travel Agencies () | ||||

| Number of Art Performance Teams () | Number of Tourism Colleges and Universities () | ||||

| Employees | Number of Employees in Public Libraries () | Employees | Number of Employees in Scenic Spots () | ||

| Number of Employees in the Cultural Centers () | Number of Employees in Starred Hotels () | ||||

| Number of Employees in Museums () | Number of Employees in Travel Agencies () | ||||

| Number of Employees of Art Performance Groups () | Number of Students in Tourism Colleges () | ||||

| Profit & Loss Effects | Number of Visitors to the Public Libraries () | Profit & Loss Effects | Operating Revenue of Scenic Spots () | ||

| Number of Visitors to the Cultural Centers () | Operating Revenue of Starred Hotels () | ||||

| Number of Visitors to the Museums () | Operating Revenue of Travel Agencies () | ||||

| Number of Audience of Art Performance Groups () | Total Number of People Received in Scenic Spots () |

| Level | Coupling Coordination Degree | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extreme imbalance | (0.0,0.1) |

| 2 | Severe imbalance | [0.1,0.2) |

| 3 | Moderate imbalance | [0.2,0.3) |

| 4 | Mild imbalance | [0.3,0.4) |

| 5 | Verge of imbalance | [0.4,0.5) |

| 6 | Reluctant coordination | [0.5,0.6) |

| 7 | Primary coordination | [0.6,0.7) |

| 8 | Intermediate coordination | [0.7,0.8) |

| 9 | Well-coordinated | [0.8,0.9) |

| 10 | High-quality coordination | [0.9,1.0) |

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moran’s I | 0.144 | 0.190 | 0.187 | 0.207 | 0.214 | 0.184 | 0.177 | 0.173 | 0.127 | 0.141 |

| Z | 2.356 | 2.480 | 2.284 | 2.520 | 2.586 | 2.450 | 2.515 | 2.530 | 2.455 | 2.353 |

| P | 0.019 | 0.014 | 0.023 | 0.012 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.019 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chi, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, J. Spatial–Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Economic Effects of China’s Cultural and Tourism Industries’ Collaborative Agglomeration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215119

Chi Y, Fang Y, Liu J. Spatial–Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Economic Effects of China’s Cultural and Tourism Industries’ Collaborative Agglomeration. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):15119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215119

Chicago/Turabian StyleChi, Yihan, Yongheng Fang, and Jiamin Liu. 2022. "Spatial–Temporal Evolution Characteristics and Economic Effects of China’s Cultural and Tourism Industries’ Collaborative Agglomeration" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 15119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215119