1. Introduction

According to the United Nations Population Division, 54.5 per cent of the world’s population were living in urban settlements in 2016, whereas by 2030 it is expected that 60 per cent of people globally will live in urban areas with one in every three people living in cities of at least half a million inhabitants [

1]. Urbanization poses enormous challenges for cities around the world, particularly in the Global South: adequate infrastructure, affordable housing, public transport, decent employment, access to services, clean energy, water and waste management, food security, environmental quality, etc. To address these challenges, the recently adopted UN-Habitat New Urban Agenda (NUA) [

2] has set a new standard for sustainable urban development

“specially committed to:

Provide basic services for all citizens;

Ensure that all citizens have access to equal opportunities and face no discrimination;

Promote measures that support cleaner cities;

Strengthen resilience in cities to reduce the risk and the impact of disasters;

Take action to address climate change by reducing their greenhouse gas emissions;

Fully respect the rights of refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons regardless of their migration status;

Improve connectivity and support innovative and green initiatives;

Promote safe, accessible and green public spaces”.

Now national governments, as well as regional and local authorities, must take their turn in implementing the NUA and to that end, establishing the right technical and financial partnerships across the international community is of great importance. Likewise, national urban policies should be developed to support the implementation of the NUA by means of urban regulations, urban planning and design, and municipal finance. However, in practise, bridging the gap between national and regional policies and local intervention through concrete projects is far from being an easy task.

Ecocity projects can contribute to the achievement of the objectives of the NUA if used, not as rigid “models” of sustainable urbanization (much less as physical “models”) to be replicated worldwide as intended by some of them [

3,

4], but as a transformative force and a laboratory for new ideas as argued by Rapoport [

5]. Despite the constant challenge of finding a balance between utopian visions and concrete realizations [

6], which has raised considerable criticism, ecocity projects can have a positive impact in terms of increasing environmental awareness, setting examples of good practice that might inspire new ecocity developments, testing innovative solutions, or sparking a public debate on what is a sustainable city. The benefits of demonstration projects is shown by the research on Northern European ecological communities conducted by Saunders [

7].

More concretely, the EcoCity concept developed by VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd. (VTT) for sustainable community and neighbourhood regeneration and development has been designed to make possible the formulation of solutions that can be adapted to different local conditions supported by specific methodologies and effective facilitation processes and skills. As shown by Antuña-Rozado et al. [

8], during the EcoMedellín project VTT’s EcoCity facilitation enabled on the one hand the articulation of the “grey” and the “green” components, and on the other the change of scale by moving from national and regional policies to a specific local project [

8]. Therefore, in this sense the EcoCity concept, methodologies and facilitation can help to bridge the gap identified in the implementation of the NUA. As it will be explained along the article, VTT’s EcoCity concept is flexible and constantly evolving to allow the inclusion of other relevant perspectives like those introduced by digitalization (smart solutions), Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) or circular economy, if considered pertinent (and feasible) in the course of the dialogue established with local stakeholders. It seems necessary to clarify that “EcoCity” refers to VTT’s own developed concept and related activities, whereas “ecocity” or “ecocities” refer to the generic concept, activities and examples.

Looking at the existing literature, there seems to be a general consensus on the fact that there is not a universally accepted definition of what is an ecocity, as pointed out by a number of authors like Roseland [

9] or Joss [

10]. This has led to a division in opinion between those that believe that the lack of a clear definition is detrimental to the validity of the concept, and those that consider it positive since it leaves enough margin for the development of locally attuned solutions in a variety of contexts worldwide like Surjan and Shaw [

11] or Wong and Yuen [

12]. The first ones often insist on the need for assessment frameworks and standards like the Ecocity Framework and Standards developed by Ecocity Builders & the International Ecocity Advisory Committee [

13], or indicators as proposed by Kline [

14]. VTT’s EcoCity concept probably lies somewhere in the middle of these two positions since as corroborated by the authors’ experience, considerable flexibility is needed for local adaptation, but at the same time it is necessary to set targets and follow them up, as well as to monitor the performance in specific areas (e.g., air, energy, water).

There seems to be no consensus either regarding the scale of ecocity projects, which in practice can range from relatively small interventions (neighbourhood regeneration and urban retrofits) to whole new towns like those built in Asia and the Middle East. This diversity has led authors like Jabareen to define the ecocity as an

“umbrella metaphor that encompasses a wide range of urban-ecological proposals that aim to achieve urban sustainability” [

15], which matches quite well the authors’ observations in all VTT’s EcoCity related activities so far.

The in-depth critical analysis of concrete case studies carried out by some authors like e.g., Caprotti or Cugurullo, has contributed to expose the multi-faceted reality of ecocities and the challenges of the ecocity development process [

16,

17], both relevant issues not sufficiently covered by the literature. It is for such process, particularly in its early stages that VTT’s EcoCity concept provides a structured yet flexible framework for conducting the complex dialogue leading to ecocity implementation, which may be its main differentiating factor. Therefore, this article aims at contributing to the abovementioned debate on the complexities and nuances of the process towards the implementation of ecocities worldwide, as well as on the varying local conditions requiring adaptation. This contribution is half way between theory and practice, inasmuch as VTT’s EcoCity concept is placed in the context of the ongoing ecocity debate, thus adding to its intellectual side, but the content and reflections provided originate from practical experience in guiding and supporting the multi-stakeholder dialogue, as the Libyan case study presented illustrates.

2. Research Aim, Methodology and Novelty of the Approach

VTT’s EcoCity concept has been designed and improved through collaboration with local partners and stakeholders for the improvement of human settlements around the world, especially in the Global South. The aim of the research shown here is two-folded. On the one hand, to frame the theoretical and historical underpinnings of the concept in relation to the general ecocity debate, thus completing the trilogy including the two previous articles [

8,

18] focusing on its practical side and covering the methodologies and facilitation processes and skills specifically developed to support the implementation of the concept. On the other hand, to exemplify through a case study how the concept is applied in practice in a specific local context

The methodology followed consists of first explaining why and how the concept developed by VTT emerged, and its links to the Finnish urban development tradition illustrated through relevant examples (Tapiola Garden City, Otaniemi High-Tech Park, and Eco-Viikki) and future opportunities provided by emerging concepts (e.g., Circular Economy and Nature-Based Solutions); then discussing its main components in relation to different approaches, proponents, scope, etc., within the general ecocity panorama; after that showing how the concept and its objectives are communicated and carried forward, briefly illustrated through a case study (Libya); and finally drawing conclusions from the experience in numerous EcoCity activities and projects worldwide.

In short, VTT’s EcoCity concept relies upon: (1) the close collaboration with reliable local partners; (2) the adaptation of the solutions proposed to the local conditions; (3) the effective participation of key stakeholders; and (4) the use of specific methodologies and facilitation processes and skills mentioned above. The previous aspects when considered separately do not necessarily constitute a novelty, but their integration into a holistic and flexible framework certainly does. Seen retrospectively, the fact that such framework is used to guide and support the multi-stakeholder dialogue ultimately leading to ecocity implementation, invariably complex and full of challenges, particularly in the first stages, is particularly value-adding. In addition, experience corroborates the importance of adequate assessment tools and indicators in order to set targets and monitor their degree of achievement. Consequently, the concept is enriched and strengthened with each case study, and in turn, the concept thus improved benefits subsequent case studies, resulting in a sort of “continuous improvement feedback loop” which is another novel aspect.

3. Background and Main References

The ecocity concept presented was formulated in Finland, a Nordic country with a long history of promoting sustainable development, both nationally and internationally. The Finnish National Commission on Sustainable Development (FNCSD) was established in 1993, following the repercussion of the Brundtland Commission Report [

19], and the 1992 Rio Conference with its subsequent Declaration on Environment and Development [

20]. Since its inception the FNCSD has implemented numerous programmes and strategies, the latest of which, “The Finland we want 2050 —Society’s Commitment to Sustainable Development” was adopted in 2013 and updated in 2016 in alignment with the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

21]. The Finnish approach towards sustainable development is a holistic one, integrating

“the wellbeing of people and the environment, a healthy and sustainable economy and the promotion of sustainable lifestyles” [

22]. VTT’s EcoCity concept stands on the same holistic approach while trying to respond to the needs and challenges typically associated to sustainable community and neighbourhood regeneration in the Global South. To achieve successful results in this regard, close collaboration with reliable local partners and relevant stakeholders has proved to be of crucial importance, as well as adaptation to varying local conditions as discussed by Antuña-Rozado et al. [

8]. The references discussed in the next paragraphs should not be considered as a separate set of examples belonging to a specific domain, but as part of a much wider process spanning for decades and involving political commitment, constantly developed technical capacity, adequate legislative framework, and strong citizens’ awareness and participation. It is rather this long-term societal quest for sustainable development that should be promoted, instead of a fragmented approach marked by a series of costly flagship ecocity projects, which very often fail in fulfilling the initial expectations. Particularly successful examples of sustainable urbanization in Europe like Freiburg (Germany) or Vitoria-Gasteiz (Spain) to name a couple, corroborate the importance of an integral approach sustained in the long run.

When focusing more specifically on Finland’s urban planning and development tradition, the main references of VTT’s EcoCity concept are Tapiola Garden City (1950s and 1960s, Espoo), Otaniemi High-Tech Park (1960s, Espoo) and Eco-Viikki (1990s, Helsinki). Based on Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City (1898–1902) and its first practical applications in England (Letchworth, Hampstead Garden Suburb and Welwyn Garden City) [

23], Tapiola Garden City in Espoo, a municipality next to Helsinki, was built by the Finnish Housing Foundation in response to the great post-war social demand for housing. The project responded mainly to the vision of Heikki von Hertzen, the executive director of the Housing Foundation at the time, who wanted to create

“a modern city that would address the housing shortage in Helsinki and would be both economically viable and beautiful” [

24]. His somehow utopian vision went beyond the dwellings and aimed at building a healthy city that would provide an alternative to what was perceived at the time as an

“oppressive urban environment”, in the form of a self-sufficient community providing all services and facilities necessary to meet the needs of 30,000 inhabitants including the surrounding districts [

25].

The original plans for Tapiola Garden city made by Otto-Iivari Meurman were modified by the Housing Foundation and then handed over to a group of prominent Finnish architects like Alvar Aalto, Aarne Ervi and Kaija Siren who were commissioned to design their own part of the city and its buildings. Other innovative features of Tapiola Garden City, even more considering the period during which it was built, was the multi-disciplinary and participatory approach taken. The city was the result of a successful teamwork that involved architects, civil engineers, sociologists, landscape architects, and experts in domestic science and child welfare. Participation was considered at different stages of its development, and even the name of the city itself (“Tapiola” derives from Tapio, the Finnish forest god mentioned in Kalevala) was chosen through public competition [

26]. An adequately validated participation of key stakeholders (see Antuña et al., [

8]) is an essential component of VTT’s EcoCity concept, which builds on the participatory tradition of Finnish urbanism exemplified by Tapiola Garden City.

The development of Otaniemi High-Tech Campus was initiated in 1946 when it was decided to move the Helsinki University of Technology (TKK, nowadays Aalto University) and the Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT) from Helsinki city centre to Otaniemi in Espoo. Gradually, different facilities were built and by the beginning of the 70s, most departments of TKK had moved to the new location [

27]. The heart of Otaniemi High-Tech Campus consists of the main university buildings like the auditorium, the library, administration offices, a number of faculties and a small shopping centre. Close by there is housing and other facilities such as a convention centre, a sports hall, a chapel and a hotel.

At present, Otaniemi is a technology and innovation hub that brings together academia, research and high-tech companies (also start-ups) in a very stimulating natural environment well accessed by public transport, including the recently inaugurated metro line between Helsinki and Espoo. Very soon Otaniemi will also host the European Space Agency’s (ESA) new arctic space accelerator, and the first European United Nations Technology Innovation Lab (UNTIL) at the recently established A Grid start-up hub [

28]. Like Tapiola Garden City and Otaniemi High-Tech Campus, VTT’s EcoCity concept promotes an urban model where nature is strongly present, and within walking distance, in the form of forests and wild areas, historic mansion parks, other parks of various sizes, gardens, and lakes for all the citizens to enjoy its biodiversity and benefit from the ecosystem services provided.

Eco-Viikki has attracted a lot of attention both nationally and internationally since it was built in the 1990s, following an architectural competition that specified that proposals had to be ecologically sustainable through the minimization of the use of non-renewable energy sources and rapidly diminishing raw materials, reduction of pollution levels, noise and waste; minimization of the stress on natural resources and local ecosystems; residents empowerment and awareness raising on ecological sustainability [

29]. Research programmes for Sustainable Development and Ecological Buildings were initiated to establish what sustainable development in urban planning and building entails. The need to test ecological principles in practice resulted in an invitation to local authorities around the country to work on experimental ecological construction in January 1994 [

30].

Figure 1 shows a few images of the main references discussed.

In Helsinki, Viikki was chosen as a test bed because it was sufficiently urban, connected to the existing communal structure and easily accessible by public transport. Already at an early stage, there was an awareness that ecological criteria were required to assess the ecological profile of the neighbourhood. Since no such measures were in use in Finland at the time and it was felt that various criteria used elsewhere could not be directly applied to Finnish conditions, a group of building consultants defined those specifically for Viikki in 1997. These criteria were used to assess the emissions, resource efficiency, human health, biodiversity and local food production of the projects to be developed [

31]. This constitutes a clear example of adaptation to the local context, of the assessment framework in this case, which is a defining characteristic of the EcoCity concept discussed. The winning entry (of 91 proposals submitted) was based on a finger-like structure where the buildings are grouped around residential precincts (“home zones” where pedestrians have the right of way), with “green fingers” penetrating between the built areas, so that every plot is directly linked to the green areas. The major part of the buildings were directed optimally towards the south [

29].

Figure 2 shows both the criteria established and the solutions adopted for Eco-Viikki.

Beyond the initial ecological requirements, small-scale solar energy production and storm water management solutions, together with other sustainable technologies have been tested and monitored in Viikki. An extensive post-occupancy analysis identified the most successful applications from the residents’ perspective. The findings indicated that, despite of real energy and water consumption levels being higher than projected, the strategies implemented still reduced those below standard development [

32]. Developing an assessment framework that responds to the local conditions and following it up throughout the ecocity development process, as well as complementing it with monitoring of specific areas of performance (e.g., energy, water, etc.), is also encouraged when conducting a dialogue with stakeholders guided by VTT’s EcoCity concept.

Although Eco-Viikki reflects its time, in the mid-1990s ecology was almost a synonym for sustainability, it managed to show how ecological sustainability goals can create not only ecologically-friendly, but also socially-mixed urban living environments with numerous options concerning their financing and forms of ownership. The solutions created originally from an ecological viewpoint gave the area a positive identity, increased residents’ initiative and sense of community, added life to the shared yards, and increased the opportunities for inhabitants of all ages to spend time outdoors.

Sustainable Urban Development in Finland During Recent Years

Many relevant initiatives in terms of sustainable urban (and regional) development and regeneration have followed Eco-Viikki, in not only Helsinki, but also all across the country. An exhaustive description of those would make this article too long; therefore, what follows is rather an overview of where the process has led focusing on its present highlights. From a wider perspective and with regards to sustainable development, current initiatives in Finland are to be framed within the most important international agreements (already mentioned), and European strategic documents like the White Paper on the Future of Europe [

33] or the recently published Towards a Sustainable Europe 2030 [

34].

To its long tradition in supporting sustainable development, Finland can also add the accomplishment of having developed the world’s first road map to a circular economy, “Leading the cycle—Finnish road map to a circular economy 2016–2025” [

35]. Led by the Finnish Innovation Fund, SITRA, the road map outlines the steps towards sustainable success through “

pioneering solutions to ensure that economic growth and increased well-being are no longer based on the wasteful use of natural resources”. With an emphasis on concrete practical actions that can help to accelerate the transition to a circular economy, the road map gathers a collection of best practices and pilots involving all kinds of stakeholders (ministries, regions, cities and municipalities, companies, universities, research organizations, etc.). The focus areas for these actions are Sustainable food system, Forest-based loops, Technical loops, Transports and logistics, and Common actions.

Among the Finnish cities and municipalities committed to the development of innovative circular economy solutions (Ii, Jyväskylä, Kuopio, Lahti, Lappeenranta, Porvoo, Riihimäki, Rovaniemi, Turku and Vantaa), the city of Lahti constitutes a leading example of integrated waste management, not only in households, but also at an industrial level. If everything goes as planned, incineration and landfilling of waste in Lahti will stop by 2050. Moreover, the Päijät-Häme region, to which Lahti belongs, published in 2017 the first regional road map for circular economy. This environment is attracting all kinds of Cleantech companies.

In addition to circular economy, some Finnish cities and municipalities are also pioneering the development and implementation of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) in response to climate change derived challenges. As an interesting example, Tampere, the third largest city in Finland, is investing in innovative co-created NBS for storm water management and the prevention of flooding since, according to the latest projections, rainfall in Finland will increase significantly in the coming years due to climate change [

36]. Other challenges are air and water pollution, and reduced biodiversity. Tampere’s main NBS demonstration site is Vuores, a green district to be completed by 2030, providing residence for 13,000 people and 3000 to 5000 jobs (see

Figure 3). The NBS demonstrated in Vuores will be scaled up and further developed in Hiedanranta, a former industrial area to be transformed into a residential area for 25,000 inhabitants and more than 10,000 jobs.

In the authors’ view, there seems to be potential for “cross-fertilization” between circular economy and NBS, and eco-urbanism. However, since these can be still considered emerging concepts, there are not many examples of such hybridization.

5. A Libyan Case Study

This section aims at illustrating through a case study how VTT’s EcoCity concept is applied in practice to specific contexts worldwide, in collaboration with local partners and with the participation of relevant stakeholders.

In June 2012, the Ministry of Housing and Utilities of Libya (MHU) conducted a study trip to Finland to gather knowledge on Finnish expertise, solutions and technologies for the sustainable built environment. The trip included a number of site visits and meetings with relevant Finnish actors (including VTT), and ended with the drafting of a “Road Map on Finnish-Libyan cooperation in the field of Housing and Utilities” by the Unit for Northern Africa of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The Road Map stated that “as a follow up, a feasibility study of Libyan ecocities could be made in collaboration with local partners, focusing on aspects of highest priority, e.g., drinking water, wastewater management, housing, etc.” This resulted in a Fact Finding Mission to Libya carried out by VTT in June 2013 and organized by MHU with the overall objective of supporting sustainable community regeneration and development in the country covering a number of aspects like urban planning, water supply, waste management, affordable housing and capacity building on these issues. VTT’s EcoCity concept was used as the framework for the definition of the process’ phases: Phase I—Fact Finding Mission to understand better local priorities and resources and to prepare the next phase; Phase II—Feasibility Study for development and capacity building for the local stakeholders; and Phase III—Implementation. However, despite the plans for continuation and the efforts made together with the local partners to cover also Phases II and II, due to the circumstances only Phase I illustrated here could be completed. In this context, Phase I—Fact Finding Mission to Libya consisted of the following tasks:

Understanding local priorities through site visits and meetings with the authorities and other key stakeholders.

Discussing the components of VTT’s EcoCity concept with local decision makers.

Meeting local business actors and academia to know better local market features, current practices and constraints, and to facilitate access to information.

Identifying potential funding instruments or bodies that might support the development and implementation of EcoCities in Libya.

Table 1 summarizes the activities arranged during the Mission and the priority topics discussed, whereas

Figure 4 shows the challenges, opportunities and risks identified during those discussions for EcoCity development in Libya. However, even though Libyan stakeholders were quite well represented and the agenda was very efficiently organized considering the relatively short time available, unfortunately civil society organizations (CSOs) and citizens associations were not engaged in those activities. This could have been solved in the subsequent phases, but as abovementioned, Phases II and III were never undertaken.

From the meetings with the different Libyan authorities and stakeholders it became clear that all the components defined for VTT’s EcoCity concept, namely Energy Efficiency, Food Security, Jobs & Services, Public Transport, Sustainable Housing, Waste Management, and Water Security as shown by Antuña et al. [

3], were very relevant in the Libyan context. Regarding the prioritization of those components, it also became evident that the emphasis should be on addressing the housing shortage in the country (around 400,000 housing units needed to be built in the coming years) while providing solutions for the serious environmental threats derived from the deficient management of wastewater and solid waste.

5.1. EcoCity Action Plan for Libya

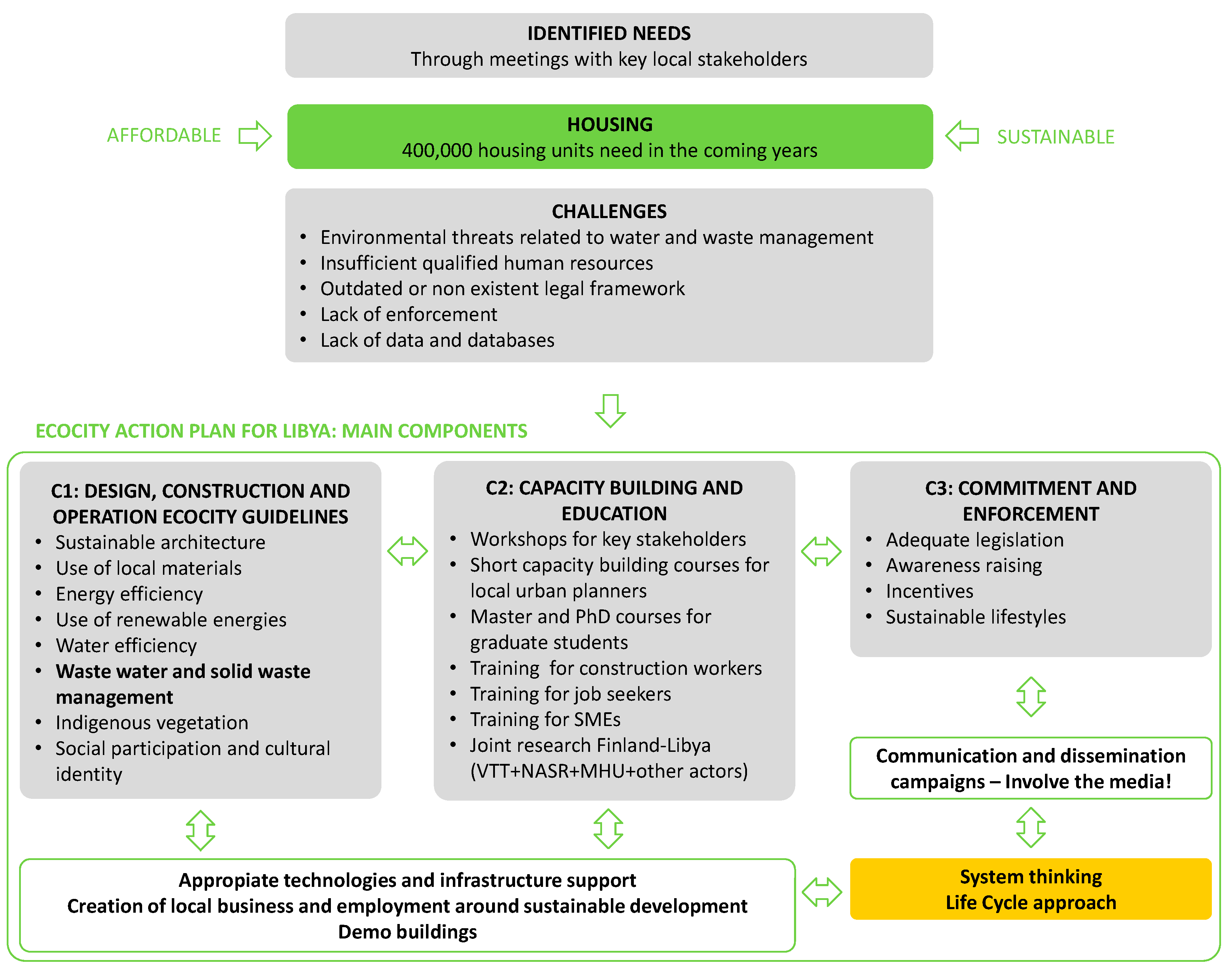

Based on the understanding of the Libyan context and needs obtained from the abovementioned discussions and targeted visits, an EcoCity Action Plan was proposed to be discussed with and validated by MHU (see

Figure 5) including three main components:

● EcoCity Guidelines for the design, construction, operation and maintenance of buildings (C1)

This component responded to the urgent need of housing and the will of the Libyan authorities to make it sustainable and to initiate a transformation towards the implementation of the EcoCity concept in Libya. In this context, the direct application and demonstration of the EcoCity principles in the Libyan environment through selected pilot projects was deemed essential.

The list included in

Figure 5 (Sustainable architecture; Use of local materials; Energy efficiency; Use of renewable energies; Water efficiency; Wastewater and solid waste management; Indigenous vegetation; Social participation and cultural identity) is not comprehensive, but it gives an idea of the principles that can be explored through the pilot projects. Addressing the problem of wastewater and solid waste management is of the utmost importance given the magnitude of the associated environmental (and social) impacts: pollution of the Mediterranean Sea, lagoons and groundwater; health and sanitation threats for the population, etc.

On the other hand, in the absence of proper building regulations and building code, the EcoCity Guidelines could serve as the first draft for the future Building Code for Libya, and as a blueprint for the Libyan administration to aid the design, construction and operation of all public buildings, including public housing. Citizens’ participation is necessary to overcome initial opposition to the implementation of EcoCity principles and fundamental if long-term results are to be achieved.

● Capacity Building and Education (C2)

To carry out the previous component successfully, it is necessary to build the capacity of all the stakeholders involved through training and education programmes, hence the activities listed in

Figure 5. Components C1 and C2 should be supported by the implementation of appropriate technologies customized to suit the Libyan context avoiding a direct application of ready-made solutions that most likely will not work in the local environment.

All along the project, the creation of local businesses and employment around sustainable development should be promoted in order to strengthen the economic tissue of the country and contribute to its growth. This explains the stress on training also Libyan SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises). To complement this activity, a business incubator could be also considered.

Finally, the construction (or renovation) of a few number of “demo buildings” around the country, in parallel to the real pilot projects, might help to exemplify the EcoCity principles and serve for instance as information points.

● Commitment and Enforcement (C3)

This important component relies heavily on the shoulders of the Libyan authorities because it requires high political commitment extended to all Libyan institutions in order to succeed in the implementation of an EcoCity Action Plan for Libya. Likewise, more enforcement is needed to ensure its application. However, this enforcement has to be supported by the development of adequate legislation, and by the raised awareness of the citizenship through education towards more sustainable lifestyles and incentives for the implementation of such sustainability measures.

Developing a dissemination and communication campaign and getting the media involved might be a good way to reach a wider audience throughout the country.

Finally, the whole EcoCity Action Plan should be considered from a lifecycle approach (taking into account the whole cycle of materials and processes) and a system thinking perspective (understanding that most often the problems are interrelated and holistic solutions are needed).

5.2. Potential EcoCity Pilot Projects in Libya

Libyan authorities were committed to the sustainable reconstruction and development of the country and to the application of EcoCity principles to new urban developments as well as to the deteriorated areas existing in most Libyan cities. It is widely accepted that good urban planning and design contributes to citizens’ wellbeing as argued by authors like Leyden et al. [

58], and fosters economic growth by enabling new business opportunities and even attracting tourism as posited by Shoval [

59].

The main components included in the Action Plan would be developed through real pilot projects in Tripoli, Benghazi and Shahat/Susa (

Figure 6). The proposed projects dealt both with urban development (new housing) and with urban regeneration (refurbishment of existing neighbourhoods), and included different building typologies.

Unfortunately, due to the worsening of the socio-political conditions in Libya (see risk in

Figure 4) shortly after Phase I was completed, it was not possible to continue towards Phase II (Feasibility Study) and Phase III (Implementation) and the whole process was left in stand-by to be resumed when the country’s situation allows.

6. Conclusions

When reflecting on the purpose and the content of VTT’s EcoCity concept in order to establish more clearly its theoretical and historical underpinnings, it becomes apparent that the concept builds on the Finnish tradition of urban planning and development, of which Tapiola Garden City, Otaniemi High-Tech Campus and Eco-Viikki are remarkable examples, as well as pioneering in many ways. For instance, the multi-disciplinary approach and strong emphasis on participation that characterize VTT’s EcoCity concept were already present in the development of Tapiola Garden City as seen in

Section 3, which at the time was rather a novelty. Many innovative solutions were successfully implemented in Eco-Viikki, even an ahead of its time introduction of NBS in the form of “green fingers” between blocks that enabled farming and composting, as well as rainwater collection. Another key component of VTT’s EcoCity concept, adaptation to the local context, typically pursued in close collaboration with local partners and stakeholders, was also of particular importance when selecting the ecological building criteria for Eco-Viikki so that they would be suitable for the Finnish conditions.

Considered from an even wider perspective, Finland’s long-standing commitment to sustainable development is defined by a holistic approach that aims at

“a prosperous Finland with global responsibility for sustainability and the carrying capacity of nature” [

22], and that also permeates VTT’s EcoCity concept. However, such supportive environment, although mostly favourable for the formulation of this type of concept, entails the risk of taking for granted certain pre-conditions that pose a great concern for the target countries. In this sense, collaboration with local partners and stakeholders has been instrumental to make explicit what were originally implicit assumptions deriving from the Nordic view on sustainable development. This can be said of the ecocity concept in general. As Lye & Chen point out, the ecocity concept has originated in North America and has developed largely based on urban practices carried out in North American, European and Australian cities, which may limit its applicability in other regions [

60]. Moreover, as Myllylä and Kuvaja argue, the ecocity concept builds on the

“societal structures and relations already in existence (namely, democracy, strong civil society participation, political accountability, etc.) in modern and post-modern societies”, and consequently it may not be able to provide adequate solutions for the challenges faced by cities in the Global South, which very often lack the pre-existing structures required [

61]. For the authors of this article this is certainly an issue not to be taken lightly, but it does not invalidate the applicability of the concept in “Southern” cities. Hence the flexible and interactive framework capable of accommodating different local interpretations of an ecocity, while respecting a series of key principles that cannot be compromised.

The importance of adaptation to the local context, for which specific methodologies have been developed, has been repeatedly stressed by Antuña-Rozado et al. [

18]. But equally important is the consensual approach towards a negotiated and agreed local definition of sustainability, and therefore an “own” definition of an EcoCity that, respecting certain non-negotiable conditions, will be ultimately appropriated by the local community as a whole. Hence the relevance of expert facilitation to support the local actors along this complex decision-making process, to help them ground their decisions on the available scientific evidence, and to link the solutions jointly formulated to existing technologies. Moreover, regardless of whether any given EcoCity project is initiated and developed top-down or bottom-up, what really matters is rather ensuring that all key stakeholders are involved through real and meaningful participation.

Somehow it can be argued that the EcoCity concept discussed here combines framework, methodologies and facilitation to support stakeholders in the Global South in the development of locally attuned EcoCity solutions following a jointly defined EcoCity vision. However, experience shows that it ultimately generates capacities and adaptation, not only on the local side but also in relation to the concept itself and its facilitators, through a dynamic of mutual learning and continuous improvement. Hopefully, this approach can help to move away from the “labelling fever” and an overreliance on technology that, according to many critical voices, affects numerous flagship ecocity projects worldwide which unfortunately have failed in engaging the community and even in creating a true sense of place as discussed by Piew & Neo [

62]. Although it can be considered that the ultimate goal is the realization of an ecocity project, or in other words, a “built” ecocity, in the authors’ view it is necessary to stress the complexity of the process leading to that realization, which very often does not receive the attention it deserves. VTT’s EcoCity concept tries to contribute precisely to the dialogue that should be conducted as part of that process, and that as such has a value in itself, which should be separated from the final outcome—the built ecocity.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the comparison between VTT’s EcoCity concept and different approaches, which was explained more in detail in

Section 4.

The Libyan case study illustrates how this dialogue is conducted. The EcoCity Action Plan for Libya drafted in collaboration with the local stakeholders attempts to build a bridge between the general vision posited by the “Road Map on Finnish-Libyan cooperation in the field of Housing and Utilities” (see

Section 5) and the formulation of specific projects in selected intervention areas by supporting and informing what is always a complex decision-making process. When compared with the Medellín case study, it can be seen how the same EcoCity concept leads to a different “Action Plan” precisely due to its flexibility, which enables adaptation to varying local contexts. The pilots identified in both cases are an important aspect in this transition towards concrete intervention projects because they connect the concept (theory) with the real examples (practice). However, the highly volatile situation in Libya, and in many other countries of the Global South for that matter, constitutes a serious hindrance for the full implemention of an ecocity transformation process, which is by nature complex and takes rather a long time to realize. The

“global north-based urban knowledge production system” as Nagendra et al. rightfully call it [

63], is supported by consolidated democracies, strong civil society participation (and awareness) and political accountability. The conditions in the Global South are very different from those that have shaped the urban development in the Global North, and therefore a new approach is required that potentiates the local capacities and pays attention to the specificities of the context. In the same paper, Nagendra et al. argue that despite the numerous challenges, cities in the Global South offer many opportunities for sustainability and have unique innovation and experimentation potential. Even though unfinished, the EcoCity path initiated in Libya may be a valid example of how to “downscale” the concept in order to make it applicable in such contexts, by focusing on specific issues according to the priorities of the country and defined case by case.