Energy Justice as Part of the Acceptance of Wind Energy: An Analysis of Limburg in The Netherlands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

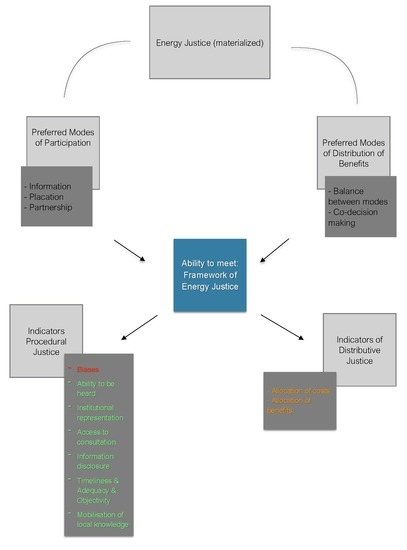

2.1. Energy Justice

2.2. Procedural Justice

2.3. Distributive Justice

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Participation

4.1.1. Used Modes of Participation in Limburg

4.1.2. Factors Important for a Perception of Procedural Justice

4.2. Distribution of Benefits

4.2.1. Used Modes of Distribution of Benefits in Limburg

4.2.2. Factors Important for a Perception of Distributive Justice

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- 1.

- Can you tell me about the development of the plans for this wind farm?

- 2.

- Can you tell what is your role concerning the wind park?

- 3.

- How were you informed about the plans of the wind project?

- 4.

- When were you informed of the plans for this wind project?

- (Question for clarification; Was the decision about where the project would be realized already taken?)

- (Question for clarification; And if so, by whom?)

- 5.

- What are the advantages of this wind energy project?

- (Question for clarification: How does the community benefit from the wind project?)

- 6.

- What are the disadvantages of this wind energy project?

- (Question for clarification; In what way does the community experience disadvantages of this wind project?)

- 7.

- What is your opinion on the distribution of benefits of the wind energy project? (profit, employment, cost of electricity)

- 8.

- What is your opinion about the distribution of the disadvantages of the wind energy project? (maintenance, environmental disadvantages)

- 9.

- What do you think is the best/most effective way to share the costs and benefits of a wind energy project?

- 10.

- Which factors are important to you in the distribution of the benefits/disadvantages of wind energy projects?

- (Question for clarification; Which factors are important to have the feeling that the distribution of costs and benefits is sound/fair?)

- 11.

- Who are involved/have been able to participate in the development and decision-making of this wind energy project?

- 12.

- Can you tell how you are involved/have been able to participate in the plans for the wind project?

- (Question for clarification; Or in the decision-making process?)

- 13.

- What did you think of the way in which you were involved/have been able to participate in the decision-making process?

- 14.

- What did you think of the timing of your involvement in the decision-making process of the wind project?

- 15.

- What was your influence on the decision-making process?

- (Question for clarification; Can you tell about your influence on the decision-making process?)

- (Question for clarification; How were your interests taken into account?)

- (Question for clarification; Was there room for other views?)

- 16.

- What do you think is an effective way to get involved in the decision-making process/to participate in the decision-making process?

- 17.

- How do you want to be involved in a decision-making process?

- (Question for clarification; Which way of involvement/participation do you prefer?)

- 18.

- Which factors are important to you in the decision-making process to feel that a decision has been made in a sound/fair way?

Appendix B

| Categories | Codes |

| Mode of participation |

|

| Modes of distribution |

|

| Factors relevant for perception of procedural justice |

|

| Factors relevant for perception of distributive justice |

|

References

- Planbureau Voor de Leefomgeving. Analyse van Het Voorstel Voor Hoofdlijnen van Het Klimaatakkoord- Hoofdstuk 14 Elektriciteit. 2018. Available online: https://www.klimaatakkoord.nl/documenten/rapporten/2018/09/28/pbl-analyse-elektriciteit (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Rijksoverheid. Wind op Land; Europees Beleid. Available online: https://www.windenergie.nl/beleid-en-regels/europees-beleid (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Provinciale Staten Limburg. Voor de Kwaliteit van Limburg; Provinciaal Omgevingsplan Limburg (POL2014). 2014. Available online: https://www.limburg.nl/onderwerpen/omgeving/omgevingsvisie/provinciaal/pol-2014-inclusief/ (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Provincie Limburg (n.d.). Windenergie. Available online: https://www.limburg.nl/onderwerpen/duurzame-energie/windenergie/ (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Regionale Energie Strategie. Noord en Midden- Limburg. 2019. Available online: https://www.regionale-energiestrategie.nl/kaart+doorklik/noord-+en+midden+limburg/default.aspx (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- Regionale Energie Strategie. Zuid- Limburg. 2019. Available online: https://www.regionale-energiestrategie.nl/kaart+doorklik/zuid+limburg/default.aspx (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- Zuidelijke Rekenkamer. Energie in Transitie: Een Vergelijkend Onderzoek Naar de Inzet van de Provincies in de Energietransitie. 2018. Available online: https://www.zuidelijkerekenkamer.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Bijlage-1-Eindrapport-Energie-in-Transitie.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Gemeentegrensoverschrijdende Ontwikkeling Windpark Greenport Venlo in Venlo en Horst aan de Maas. 2018. Available online: https://www.venlo.nl/venlo-windpark-greenport (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Devine-Wright, P. Beyond NIMBY-ism: Towards an integrated framework for understanding public perceptions of wind energy. Wind Energy 2005, 8, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhoop, N. Acceptance of wind energy and the role of financial and procedural participation: An investigation with focus groups and choice experiments. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, B.E. Renewable energy: Public acceptance and citizens’ financial participation. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Environmental Law; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Dortmund, UK, 2016; pp. 476–486. [Google Scholar]

- Mundaca, L.; Busch, H.; Schwer, S. ‘Successful’low-carbon energy transitions at the community level? An energy justice perspective. Appl. Energy 2018, 218, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, K.; Decker, T.; Menrad, K. Public participation in wind energy projects located in Germany: Which form of participation is the key to acceptance? Renew. Energy 2017, 112, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, R. Enthousiasme en Ongenoegen Over Limburgse Windmolens. NOS, 13 March 2019. Available online: https://nos.nl/artikel/2275750-enthousiasme-en-ongenoegen-over-limburgse-windmolens.html (accessed on 21 July 2019).

- Reijn, G. ‘Niemand wil zo’n Molen in Zijn Achtertuin. Maar als er Iets Tegenover Staat, is Het een Ander Verhaal’. Volkskrant, 13 August 2018. Available online: https://www.volkskrant.nl/economie/niemand-wil-zo-n-molen-in-zijn-achtertuin-maar-als-er-iets-tegenover-staat-is-het-een-ander-verhaal~bc2fd7ad/ (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Boon, F.P.; Dieperink, C. Local civil society based renewable energy organisations in the Netherlands: Exploring the factors that stimulate their emergence and development. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etriplus. Windpark Greenport Venlo. Available online: http://www.etriplus.nl/wind/ (accessed on 6 April 2019).

- Gemeente Leudal. Windenergie. Available online: https://www.leudal.nl/windenergie (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Holsgens, J. Werken Aan Het Draagvlak Voor een Windpark in Heibloem. Leudal Nieuws. 5 March 2018. Available online: https://leudal.nieuws.nl/2018/03/05/werken-aan-draagvlak-windpark-heibloem/ (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musall, F.D.; Kuik, O. Local acceptance of renewable energy—A case study from southeast Germany. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3252–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Doyon, A. Justice in energy transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2019, 31, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.; Ramasar, V.; Heffron, R.J.; Sovacool, B.K.; Mebratu, D.; Mundaca, L. Energy justice in the transition to low carbon energy systems: Exploring key themes in interdisciplinary research. Appl. Energy 2019, 233, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.H.; Cherry, T.L.; Kallbekken, S.; Torvanger, A. Willingness to accept local wind energy development: Does the compensation mechanism matter? Energy Policy 2016, 99, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankena, W.K. The concept of social justice. In Justice in General; Vallentyne, P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice, Rev. ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. Energy justice: Conceptual insights and practical applications. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, K.; Decker, T.; Roosen, J.; Menrad, K. Factors influencing citizens’ acceptance and non-acceptance of wind energy in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M. Qualitative research methods: Why, when, and how to conduct interviews and focus groups in pharmacy research. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2016, 8, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Form of Participation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Manipulation | Manipulation is about educating the people about the policy idea and/ or problem. The people being educated have usually no legitimate function or power. The policy plan is being sold. |

| Therapy | This form of participation puts emphasis on curing the people participating from their ideas. The goal is to adjust the disagreement showed by the citizens |

| Informing | This form is about informing people of ‘their rights, responsibilities and options’ [20]. The citizens can ask questions, but there is no receptiveness for the opinion of the citizens. It is a one-way flow of, often technical, information from the decision maker to the citizen. |

| Consultation | In this form the opinion of citizens is asked, but not necessarily taken into account. Policy options are not available, just consultation on one policy option takes place. The scope of options is already limited by the people in power. There are no mechanisms to assure that their opinions will be taken into account. |

| Placation | There is an information flow and the scope of policy options is not limited beforehand. The expectation is that there is some influence of the less powerful. However, the powerholders still decide and can outvote the powerless since they judge the legitimacy of the input. |

| Partnership | In this form ‘the power is redistributed through negotiation between citizens and powerholders’ [20]. There is agreement on structures to ‘share planning and decision-making responsibilities’ [20]. In this form people can initiate plans, engage in joint planning and review plans. |

| Delegated Power | Citizens have dominant power in the decision-making and are accountable for the project. They (citizens) have the power to put things on the agenda, such as new plans, and the powerholder has to negotiate. |

| Citizen Control | Citizens have control over the budget, are responsible for the process and the solution. They are in charge of the policy-making and managerial aspects. If final approval is needed from the city council, it cannot be framed as citizen control. |

| Mode of Distribution | Definition |

|---|---|

| Compensation measures | Compensation measures cover the negative consequences for affected individuals of wind energy projects, for example regarding the value of property or houses of affected citizens [11]. Examples exists of developers directly paying compensation for the perceived costs, but also agreements where it is guaranteed that citizens can sell their property at the current market value [11]. However, this form has not been identified as the most effective form of distribution so far, since the line between bribery and compensation is thin and thus faces the risk of creating trust issues which results in doubts regarding the fairness of this mode [11,25]. |

| Community Benefits | Community benefits are in contrast to compensation measures not specified to just a couple of individuals, but create benefits for the whole community and thus compensate in that sense for the local consequences of wind energy projects [11]. Community benefits are based on the equality principle since the aim is to give the people involved an equal share of the benefits [30]. An example is a local reduced electricity tariff for the affected people or the community [10]. Also, annual compensation payments to the community or part of the profit going to local funds can be noticed in the literature as a form of community benefits [10,11]. |

| Ownership | Ownership measures can be seen as the most direct form of financial participation in wind energy projects. There are different forms of citizens’ financial participation in which the degree of ownership differs. It ranges from citizens investment by shares to full community ownership of a wind turbine [11]. Ownership measures in the form of shares are based on the equity principle, since the financial benefits are proportional to how big someone’s share or investment is [30]. |

| Number | Wind Park | Established | Balance Private/Cooperation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Wind park Venlo | No | Privately initiated, but promised to include cooperations. |

| 2. | Wind park Neer | Yes | Privately initiated, but one turbine 100% of cooperation. |

| 3. | Wind park Weert | No | Share between private company and cooperation. |

| 4. | Wind park Ospeldijk | No | Share between private company and cooperation. |

| 5. | Wind park Heibloem | No | 100% cooperation. |

| 6. | Wind park Egchelse Heide | No | Share between private company and cooperation. |

| 7. | Wind park De Kookepan | No | 100% cooperation. |

| Stakeholder Categories | Stakeholders | Case Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Local wind energy cooperations | Energy cooperation A: Energy cooperation Newecoop | Ospeldijk |

| Energy cooperation B: Energy cooperation Zuidenwind | Neer (only the Coöperwieck) | |

| Energy cooperation C: Energy cooperation Leudal Energie/Energy cooperation Weert Energie | De Kookepan & Weert | |

| Energy cooperation D: Energy cooperation Reindonk Energie | Venlo | |

| Citizens | Citizen A: Village consultation Egchel | Egchelse Heide + Neer (including De Coöperwieck) |

| Citizin B: Direct stakeholder and representative of village council Ospeldijk | Ospeldijk | |

| Citizen C: Village cooperation Boerderijweg | Neer (including De Coöperwieck) + Heibloem | |

| Citizen D: NLVOW (Dutch Association for People living near Wind Turbines) | Venlo + included in general way | |

| Citizen E: Village consultation Boekend | Venlo | |

| Non-governmental organisations | NGO A: NMFL (Nature and Environment Federation Limburg) | Venlo + included in general way |

| NGO B: NMFL (Nature and Environment Federation Limburg) | Weert + included in general way | |

| NGO C: LLTB (Limburg Agriculture and Greenery Federation | Heibloem + included in general way |

| Phases of Wind Park Development | Private Development Approach | Cooperative Development Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 (development of ideas) | Information | Information + Consultation + Elements of placation + (Elements of partnership *) |

| Information + Balance between consultation and placation | Information + Balance between consultation and placation | |

| Phase 2 (implementation) | Consultation | Consultation |

| Consultation | Consultation | |

| Phase 3 (exploitation) | - | Elements of partnership |

| - | - |

| Phases of Wind Park Development | Preferred Modes of Participation |

|---|---|

| Phase 1 (Development of ideas) | Information + Placation + (Partnership *) Stakeholders want to be collectively informed and included when the location of the wind park has not yet been determined, so that there is still an open discussion about the location. Besides that, they want their interests to be taken into account. They would like to think along about alternative locations. This does not mean that they necessarily want to take part in the decision-making process, which they generally still see as a task for the municipality. In conclusion they want a broader scope of options and they want their interest being taken into account. |

| Phase 2 (Implementation) | Decision making in hands of the municipality |

| Phase 3 (Exploitation) | Partnership Data shows that the only part where citizens prefer a higher form than ’placation’ as a form of participation is regarding decisions on the distribution of benefits. They do not necessarily want to take part in deciding on the budget or what modes of distribution will be available, but they do want to determine what will happen to the money within a certain mode of distribution. * In the ‘development of idea’ phase, citizens indicate that they would also like to make a collective decision about the distribution of the ground compensation. However, this concerns a small group of landowners that is included in this division in this phase. Interestingly, the NGO did not indicate that it would prefer partnership as a form of participation at any stage. |

| Private Developed Wind Park | Cooperative Developed Wind Park |

|---|---|

| Individual compensation (not transparent) | Individual compensation (transparent) |

| Community fund | Community fund |

| Ownership in the form of financial participation | Ownership in the form of financial participation |

| Energy fund * | |

| Nature fund * |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kluskens, N.; Vasseur, V.; Benning, R. Energy Justice as Part of the Acceptance of Wind Energy: An Analysis of Limburg in The Netherlands. Energies 2019, 12, 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12224382

Kluskens N, Vasseur V, Benning R. Energy Justice as Part of the Acceptance of Wind Energy: An Analysis of Limburg in The Netherlands. Energies. 2019; 12(22):4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12224382

Chicago/Turabian StyleKluskens, Nikki, Véronique Vasseur, and Rowan Benning. 2019. "Energy Justice as Part of the Acceptance of Wind Energy: An Analysis of Limburg in The Netherlands" Energies 12, no. 22: 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12224382

APA StyleKluskens, N., Vasseur, V., & Benning, R. (2019). Energy Justice as Part of the Acceptance of Wind Energy: An Analysis of Limburg in The Netherlands. Energies, 12(22), 4382. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12224382