What Motivates Behavior Change? Analyzing User Intentions to Adopt Clean Technologies in Low-Resource Settings Using the Theory of Planned Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Considerations for Residential Energy Technology Adoption

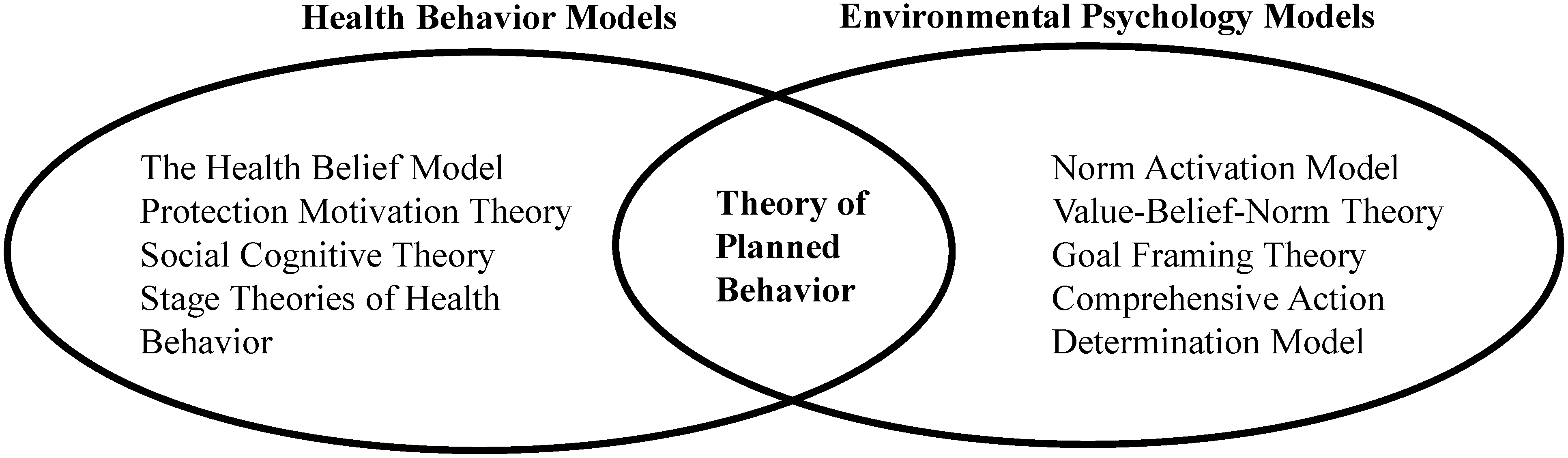

1.2. Models of Behavior

1.3. Objective and Novelty of the Paper

2. Methodology

2.1. Survey Design

- Consistency—Primarily, the questions related to each category of TPB attributes were designed for internal consistency, a measure of reliability that informs how observed variables describe the attributes of interest [63].

- Efficiency—To ensure that survey questions reflected the dominant widespread beliefs and motivations in the target community, a pilot survey was used to narrow down questions. It included open-ended questions about cooking, food, firewood collection, and power dynamics from a small group of community members and local staff of partner NGOs. The answers to these open-ended questionnaires shed light into the main attributes that play role in cooking behavior in the target communities. Then survey instrument questions were designed based on these attributes to capture a wide array of responses regarding topics such as kitchen cleanness, safety, smoke emission, and firewood consumption.

- Reliability and simplicity—Using a translation-back-translation procedure by the field staff who were native speakers of the local language, the validity of questions and their simplicity was evaluated.

- Limited bias—In the second round of data collection, local staff were trained to conduct an unbiased data collection in the way to reduce the effect of surveyor bias and their feedback were integrated in the questionnaire to reduce the socially desirable biases.

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Honduras

3.1.1. Lessons Learned

3.1.2. Data Separation and Internal Consistency

3.2. Uganda

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Survey Questions in Honduras, Baseline Study

- None 1 2 3 4 5

- A lot, try to comply

- I respect their opinion, but it doesn’t influence me

- I don’t pay attention

- I ignore them

- I try the opposite

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

- Not important moderately important

- I don’t know

- Important

- Very important

- No change a little bit

- I don’t know considerably

- A lot

- Very hard

- Hard

- I don’t know

- Easy

- Very easy

- A lot, try to comply

- I respect their opinion, but it doesn’t influence me

- I don’t pay attention

- I ignore them

- I try the opposite

- I can decide myself

- I feel I can decide by myself

- I don’t know

- I prefer to consult

- I need to consult

- Important and correct

- Good to consider

- I don’t know

- Not important

- Incorrect

- Not important

- Moderately important

- I don’t know

- Important

- Very important

- Important and correct

- Good to consider

- I don’t know

- Not important

- Incorrect

- Very much

- A little bit

- I don’t know

- Not particularly

- I don’t care what they think

- Very good designed

- Its OK

- I don’t know

- I’m not confident it’s a good design

- Its not designed based on what I need

- They discourage

- They don’t feel good

- Indifferent

- They feel good

- They encourage

- Not at all

- Not likely

- Maybe

- Most likely

- Yes for sure

- A lot, try to comply

- I respect their opinion, but it doesn’t influence me

- I don’t pay attention

- I ignore them

- I try the opposite

- Detrimental

- Somewhat harmful

- Neutral

- Somewhat beneficial

- Beneficial

- Not at all

- I’m not sure

- I don’t know

- I am confident

- I’m very confident

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

- Important and correct

- Good to consider

- I don’t know

- Not important

- Incorrect

- Not important

- Moderately important

- I don’t know

- Important

- Very important

- Not at all

- Not likely

- Maybe

- Most likely

- Yes for sure

- Its very hard to change

- It’s a little hard to change current stove

- I don’t know

- Its easy to change current stove

- Its necessary to change current stove

- Very easy

- Somewhat easy

- I don’t know

- Hard

- Very hard

- Not a problem at all

- Could be a problem

- I don’t know

- Challenging

- Very problematic

- Not important

- Moderately important

- I don’t know

- Important

- Very important

Appendix A.2. Survey Questions in Honduras, Follow-Up Study

- None 1 2 3 4

- I lot, try to comply

- I respect their opinion, but it doesn’t influence me

- I don’t pay attention

- I ignore them

- I try the opposite

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

- No difference

- Traditional stove is somewhat better

- Traditional stove is much better

- No change

- A little bit

- I don’t know

- Considerably A lot

- A lot, try to comply

- I respect their opinion, but it doesn’t influence me

- I don’t pay

- Attention

- I ignore them

- I try the opposite

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

- I can decide myself

- I feel I can decide by myself

- I don’t know

- I prefer to consult

- I need to consult

- Very difficult

- Difficult

- I don’t know

- Easy

- Very easy

- Important and correct

- Good to consider

- I don’t know

- Not important

- Incorrect

- No difference

- Traditional stove is somewhat better

- Traditional stove is much better

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

- Important and correct

- Good to consider

- I don’t know

- Not important

- Incorrect

- Very much

- A little bit

- I don’t know

- Not particularly

- I don’t care what they think

- Very well designed

- Its fine

- I don’t know

- It’s not the best design for my need

- It’s not designed based on what I need

- They discourage

- They don’t feel good

- Indifferent

- They feel good

- They encourage

- Not at all

- Not likely

- Maybe

- Most likely

- Yes for sure

- A lot, try to comply

- I respect their opinion, but it doesn’t influence me

- I don’t pay attention

- I ignore them

- I try the opposite

- Detrimental

- Somewhat harmful

- Neutral

- Somewhat beneficial

- Beneficial

- Very difficult

- Difficult

- I don’t know

- Easy

- Very easy

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

- Important and correct

- Good to consider

- I don’t know

- Not important

- Incorrect

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

- Never

- Rarely

- Sometimes

- Often

- Always

- Very difficult

- Difficult

- I don’t know

- Easy

- Very easy

- Very much

- A little bit

- I don’t know

- Not particularly

- I don’t care what they think

- No difference

- Traditional stove is somewhat better

- Traditional stove is much better

- Very important

- Important

- Doesn’t matter

- Not important

- Not important at all

Appendix A.3. Survey Questions in Uganda, Baseline Study

- None 1 2 3 4

- Very unlikely

- A little unlikely

- Neutral Somewhat likely

- Very likely

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- Burns significantly more fuelwood

- Burns a little more fuelwood

- No difference

- Burns a little less fuel wood

- Burns significantly less fuelwood

- Improved cookstove is a lot more dangerous

- Improved cookstove is a little more dangerous

- No difference

- Improved cookstove is a little more safe

- Improved cookstove is a lot more safe

- It’s very hard

- It’s a little difficult

- No difference

- It’s a little easy

- It’s very easy

- Too much more than traditional stove

- A little more than traditional stove

- No difference

- A little less than traditional stove

- Significantly less than traditional stove

- None of them

- Less than 4

- Between 4 to 7

- between 7 to 10

- More than 10 (all of them)

- Very discouraging

- A little discouraging

- Neither supportive or discouraging

- A little supportive

- Very supportive

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- My husband decides about it

- My husband decides after consulting with me

- We consult and decide together

- I decide after consulting with my husband

- It’s completely up to me

- Very hard

- A little difficult

- Neither hard nor easy

- Easy

- Very easy

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- Less than 3

- Between 3 to 5 meals

- Between 5 to 7 meals

- Between 7 to 10

- More than 10 meals

- Much worse

- Somewhat worse

- No difference

- Somewhat better

- Much better

- Not at all important

- Neutral Slightly important

- Important

- Very important

- Very uncertain

- Slightly uncertain

- Neither confident nor uncertain

- Slightly confident

- Very confident

- Very bad

- A little bad

- Not a problem

- A little good

- Very good

Appendix A.4. Survey Questions in Uganda, Follow-Up Study

- Extremely unlikely

- Unlikely

- Neutral Likely

- Extremely likely

- Never

- Seldom

- About half the time

- Usually

- Always

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree or disagree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- Improved cookstove is a lot more dangerous

- Improved cookstove is a little more dangerous

- No difference

- Improved cookstove is a little more safe

- Improved cookstove is a lot more safe

- It’s very hard

- It’s a little difficult

- No difference

- It’s a little easy

- It’s very easy

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither disagree or agree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

- None of them

- Less than 4

- Between 4 to 7

- Between 7 to 10

- More than 10 (all of them)

- Very discouraging

- A little discouraging

- Neither supportive or discouraging

- A little supportive

- Very supportive

- Not at all important

- A little important

- Slightly important Important

- Very important

- My husband decides about it

- My husband decides after consulting with me

- We consult and decide together

- I decide after consulting with my husband

- It’s completely up to me

- Very hard

- A little difficult

- Neither hard nor easy

- Easy

- Very easy

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Neither agree or disagree Agree

- Strongly agree

- Never

- Seldom

- Sometimes

- Usually

- Almost always

- Not at all important

- Neutral

- Slightly important

- Important

- Very important

- Very hard

- A little difficult

- Neither hard nor easy

- Somewhat easy

- Very easy

- Very bad

- A little bad

- Not a problem

- A little good

- Very good

- Not important at all

- A little important

- Fairly important

- Important

- Very important

References

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. A global perspective on domestic energy deprivation: Overcoming the energy poverty-fuel poverty binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCarty, N.A.; Bryden, K.M. Costs and impacts of potential energy strategies for rural households in developing communities. Energy 2017, 138, 1157–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Johnson, M.; Kay, E.; Pannu, R.; Beltramo, T.; Derby, E.; Harrell, S.; Davis, C.; Petach, H. Maximizing the benefits of improved cookstoves: Moving from acquisition to correct and consistent use. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2014, 2, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Legros, G.; Havet, I.; Bruce, N.; Bonjour, S.; Rijal, K.; Takada, M.; Dora, C. The Energy Access Situation in Developing Countries: A Review Focusing on the Least Developed Countries and Sub-Saharan Africa; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N.G.; Bryden, K.M. Factors affecting fuelwood consumption in household cookstoves in an isolated rural West African village. Energy 2012, 46, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; AlMazroaMD, M.A.; Amann, M.; AndersonMD, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, K.R.; Bruce, N.; Balakrishnan, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Balmes, J.; Chafe, Z.; Rehfuess, E. Millions dead: How do we know and what does it mean? Methods used in the comparative risk assessment of household air pollution. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramanathan, V.; Carmichael, G. Global and regional climate changes due to black carbon. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, R.; Drigo, R.; Ghilardi, A.; Masera, O. The carbon footprint of traditional woodfuels. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masera, O.R.; Bailis, R.; Drigo, R.; Ghilardi, A.; Ruiz-Mercado, I. Environmental burden of traditional bioenergy use. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2015, 40, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.J.; Pattanayak, S.K. Who adopts improved fuels and cookstoves? A systematic review. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Edwards, R.; Masera, O. Improved stove programs need robust methods to estimate carbon offsets. Clim. Chang. 2010, 102, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Mercado, I.; Canuz, E.; Smith, K.R. Temperature dataloggers as stove use monitors (SUMs): Field methods and signal analysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 47, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeuland, M.A.; Bhojvaid, V.; Kar, A.; Lewis, J.J.; Patange, O.; Pattanayak, S.K.; Ramanathan, V. Preferences for improved cook stoves: Evidence from rural villages in north India. Energy Econ. 2015, 52, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, A.M.; Dwivedi, P.; Bailis, R.; Hildemann, L.; Miller, G. Low demand for nontraditional cookstove technologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 10815–10820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mortimer, K.; Ndamala, C.B.; Naunje, A.W.; Malava, J.; Katundu, C.; Weston, W.; Wang, D. A cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstove intervention to prevent pneumonia in children under 5 years old in rural Malawi (the Cooking and Pneumonia Study): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pope, D.; Bruce, N.; Dherani, M.; Jagoe, K.; Rehfuess, E. Real-life effectiveness of ‘improved’stoves and clean fuels in reducing PM2.5 and CO: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2017, 101, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.L.; Peel, J.L.; Burch, J.B.; Nelson, T.L.; Robinson, M.M.; Conway, S.; Reynolds, S.J. Impact of improved cookstoves on indoor air pollution and adverse health effects among Honduran women. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2009, 19, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addict. Behav. 2002, 27, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, N.D.; Pakravan, M.H.; MacCarty, N.A. Development of a practical evaluation for cookstove usability. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2019, 48, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Hashim, N.H.N.; Rashid, M.; Omar, N.A.; Ahsan, N.; Ismail, M.D. Small-scale households renewable energy usage intention: Theoretical development and empirical settings. Renew. Energy 2014, 68, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, Y.; Greig, C.; van de Fliert, E. Resistance in rejecting solid fuels: Beyond availability and adoption in the structural dominations of cooking practices in rural India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 46, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.F.; Openshaw, K.; Smith, K.R.; van der Plas, R. What makes people cook with improved biomass stoves? A comparative international review of Stove Programs. In World Bank Technical Paper; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Katz, B. Change by design. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2011, 28, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Duflo, E.; Greenstone, M. Up in smoke: The influence of household behavior on the long-run impact of improved cooking stoves. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2016, 8, 80–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Conzelmann, G. Incorporating social impact on new product adoption in choice modeling: A case study in green vehicles. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2014, 32, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Sociality, Rationality, and the Ecology of Choice. In Choice Modelling: The State-of-the-Art and the State-of-Practice; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adrianzén, M.A. Social capital and improved stoves usage decisions in the northern Peruvian Andes. World Dev. 2014, 54, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, P.; Igdalsky, L. Sustained uptake of clean cooking practices in poor communities: Role of social networks. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 48, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Mehta, S. Poverty, gender, and empowerment in sustained adoption of cleaner cooking systems: Making the case for refined measurement. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 19, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürisoo, M.; Lambe, F.; Osborne, M. Beyond buying: The application of service design methodology to understand adoption of clean cookstoves in Kenya and Zambia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thandapani, S.; Woodbridge, R. Assessing the Benefits of Early Stage Design Research of Rural BoP-Focused Energy Solutions in Urban Settings. In Proceedings of the ICoRD’11 International Conference on Research into Design, Bangalore, India, 10–12 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A.; Cervone, D. Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1986, 38, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Mishra, R. A Review of Evolution of Theories and Models of Technology Adoption. Indore Manag. J. 2014, 6, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeren, P.; Abraham, C. The Health Belief Model. In Predicting Health Behaviour; Conner, M., Norman, P., Eds.; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; Steg, L.; Reser, J.P. Environmental Psychology. In The IAAP Handbook of Applied Psychology; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 440–470. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner, C.A. Decision Models—What Psychological Theories Teach Us about People’s Behaviour. In the Psychology of Pro-Environmental Communication; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Consumer attitudes and behavior: The theory of planned behavior applied to food consumption decisions. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2015, 70, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Shukri, M.; Jones, F.; Conner, M. Work Factors, Work-Family Conflict, the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Healthy Intentions: A Cross-Cultural Study. Stress Heal. 2016, 32, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.-F.; Malesios, C. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowsari, R.; Zerriffi, H. Three dimensional energy profile: A conceptual framework for assessing household energy use. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7505–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Zerriffi, H. From cookstove acquisition to cooking transition: Framing the behavioural aspects of cookstove interventions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 42, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Sheeran, P.; Johnston, M. From health beliefs to self-regulation: Theoretical advances in the psychology of action control. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 569–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maddux, J.E. Expectancies and the social–cognitive perspective: Basic principles, processes, and variables. In How Expectancies Shape Experience; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 2249–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- French, D.P.; Hankins, M. The expectancy-value muddle in the theory of planned behavior—And some proposed solutions. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falko, F.; Presseau, S.J.; Vera, A.-S. Time to retire the theory of planned behavior. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. Theory of Planned Behaviour Questionnaire. Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Science 2013; University of Massachusetts Amherst: Amherst, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hankins, M.; French, D.; Horne, R. Statistical guidelines for studies of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol. Health 2000, 15, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCarty, N.A. Development and Use of an Integrated Systems Model to Design Technology Strategies for Energy Services in Rural Developing Communities. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.; Eccles, M.P.; Johnston, M.; Walker, A.E.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Foy, R.; Bonetti, D. Constructing Questionnaires Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Manual for Health Services Researchers; Centre for Health Services Research: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oluka, O.C.; Nie, S.; Sun, Y. Quality assessment of TPB-based questionnaires: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trochim, W.M.; Donnelly, J.P. Research Methods Knowledge Base; Atomic Dog Publishing: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jann, B.; Long, J.S. Tabulating SPost results using estout and esttab. Stata J. 2010, 10, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iarossi, G. The Power of Survey Design A User’s Guide for Managing Surveys, Interpreting Results, and Influencing Respondents; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge, J.; Witton, J.; Elbourne, D.R. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodou, D.; de Winter, J.C. Social desirability is the same in offline, online, and paper surveys: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, S.D.; List, J.A. Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2011, 3, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nederhof, A.J. Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 15, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, A.; Anderson, J.A. On the existence of maximum likelihood estimates in logistic regression models. Biometrika 1984, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, G.; Schemper, M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakravan, M.H.; MacCarty, N.A. Design for clean technology adoption: Integration of usage context, user behavior, and technology performance in design. J. Mech. Des. 2020, 142, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, M.H.; MacCarty, N.A. An Agent-Based Model for Diffusion of Clean Technology Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Mech. Des. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

| 1. ATB | Attitude Toward Behavior | Outcome of an individual’s personal beliefs and his/her evaluations regarding validity of such beliefs. |

| 2. SN | Social and Subjective Norms | Outcome of an individual’s normative beliefs about a specific behavior, the extent to which people important to the person approve or disapprove the behavior, and personal evaluation of the social pressure for conforming to perceived normative beliefs. |

| 3. PBC | Perceived Behavioral Control | An individual’s perception for the control s/he has over the behavior is a function of her control beliefs and the power s/he feels in such control beliefs. |

| Honduras | Uganda | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size (households) | 379 | 175 |

| Number of villages | 8 | 2 |

| Affected population | 1765 | 581 |

| Number of children (under 17) | 684 (39% of affected population) | 204 (35% of affected population) |

| Main cook’s age distribution (years) | Minimum: 15 Maximum: 94 Average: 37.4 Std. dev.: 14.5 | Minimum: 15 Maximum: 75 Average: 36.16 Std. dev.: 15.32 |

| Income average (per week) | 770 HNL (~32 USD) | 24,000 UGX (~6.70 USD) |

| Education (primary income earner) | No education 70% Incomplete primary 30% | No education 10% Incomplete primary 17% complete primary 28% Incomplete secondary 12% Complete secondary 20% College/university 11% |

| ATB1 | ATB2 | SN1 | SN2 | PBC1 | PBC2 | Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATB 1 | 1.0 | ||||||

| ATB 2 | 0.46 *** | 1.0 | |||||

| SN 1 | 0.11 ** | 0.16 *** | 1.0 | ||||

| SN 2 | 0.11 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.12 ** | 1.0 | |||

| PBC 1 | 0.10 * | 0.12 ** | 0.06 | −0.02 | 1.0 | ||

| PBC 2 | 0.08 | 0.17 *** | −0.01 | −0.10 * | 0.17 *** | 1.0 | |

| Intention | 0.16 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.14 ** | 0.15 *** | 1.0 |

| Mean | 3.54 | 3.48 | 3.33 | 3.52 | 2.72 | 3.05 | 3.81 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.498 | 0.50 | 1.068 | 0.50 | 1.096 | 1.488 | 0.415 |

| ATB1 | ATB2 | SN1 | SN2 | PBC1 | Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATB 1 | 1.0 | |||||

| ATB 2 | 0.35 *** | 1.0 | ||||

| SN 1 | 0.14 *** | −0.05 | 1.0 | |||

| SN 2 | 0.14 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.14 ** | 1.0 | ||

| PBC 1 | 0.03 | 0.11 ** | 0.02 | −0.09 * | 1.0 | |

| Intention | −0.13 ** | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 1.0 |

| Mean | 4.74 | 4.77 | 4.47 | 4.26 | 4.89 | 2.66 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.457 | 0.440 | 0.828 | 1.138 | 0.551 | 0.600 |

| Baseline Model I | Baseline Model II | Baseline Model III | Follow-Up Model I | Follow-Up Model II | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Will you cook your principal meals mainly with (ICS brand)? | How many meals do you cook each day with the (ICS brand)? | |||

| Independent Variable | |||||

| ATB 1: Fuelwood consumption | −0.3587 (0.2997) | −0.2982 (0.3351) | |||

| ATB 2: Smoke emission | 0.6143 * (0.6633) | 0.6305 (0.7230) | 0.7361 * (0.8713) | −0.7594 ** (0.3658) | −0.8395 ** (0.3285) |

| SN 1: Support of friends and family | −0.1009 (0.3222) | −0.0209 (0.1786) | |||

| SN 2: Importance of opinion of friends and family | −0.0279 (0.1998) | 0.0154 (0.1980) | −0.1325 (0.1267) | −0.1599 (0.1252) | |

| PBC 1: Obtaining permission or not | 0.3449 *** (0.1621) | 0.3811 *** (0.1758) | 0.0178 (0.2112) | 0.0855 (0.2112) | |

| PBC 2: Feasibility of changing habits | 0.2565 * (0.1781) | 0.2751 * (0.2081) | 0.2836 * (0.2093) | ||

| N | 255 | 239 | 237 | 297 | 309 |

| Wald Chi-squared | 6.47 * | 18.28 *** | 19.50 *** | 7.34 | 7.66 * |

| AIC | 223.5 | 205.7 | 202.2 | 434.4 | 456.5 |

| BIC | 237.7 | 223.0 | 223.0 | 464.0 | 478.9 |

| Log pseudo likelihood | −107.8 | −97.83 | −95.11 | −209.2 | −222.3 |

| ATB1 | ATB2 | SN1 | SN2 | PBC1 | PBC2 | Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATB 1 | 1.0 | ||||||

| ATB 2 | 0.29 *** | 1.0 | |||||

| SN 1 | 0.14 * | 0.15 ** | 1.0 | ||||

| SN 2 | −0.06 | 0.12 * | 0.18 ** | 1.0 | |||

| PBC 1 | −0.09 | 0.12 * | 0.19 *** | 0.21 *** | 1.0 | ||

| PBC 2 | 0.02 | 0.12 * | 0.26 *** | 0.13 * | 0.41 *** | 1.0 | |

| Intention 1 | 0.19 ** | 0.38 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.07 | 1.0 |

| Intention 2 | −0.03 | 0.16 ** | 0.20 *** | 0.15 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.23 *** | 0.32 *** |

| Mean | 3.53 | 3.56 | 3.60 | 2.82 | 3.12 | 3.07 | 3.37 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.677 | 0.602 | 0.913 | 0.987 | 1.443 | 1.168 | 0.988 |

| ATB1 | ATB2 | SN1 | SN2 | SN3 | PBC1 | PBC2 | PBC3 | Int.1 | Int.2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATB1 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| ATB2 | 0.36 *** | 1.0 | ||||||||

| SN1 | 0.24 ** | 0.18 * | 1.0 | |||||||

| SN2 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.27 ** | 1.0 | ||||||

| SN3 | 0.20 * | 0.07 | 0.19 * | 0.32 *** | 1.0 | |||||

| PBC1 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 1.0 | ||||

| PBC2 | 0.32 *** | 0.19 * | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.41 *** | 1.0 | |||

| PBC3 | 0.22 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.19 * | 0.00 | 0.17 | −0.08 | 0.12 | 1.0 | ||

| Int.1 | 0.33 *** | 0.28 *** | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.21 ** | 0.06 | 0.35 *** | 0.24 ** | 1.0 | |

| Int.2 | 0.20* | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.14 | 0.27 *** | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.32 *** | 0.44 *** | 1.0 |

| Mean | 3.63 | 3.44 | 3.76 | 2.51 | 3.23 | 3.62 | 3.38 | 3.19 | 3.41 | 3.53 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.593 | 0.567 | 0.501 | 1.554 | 0.835 | 0.830 | 0.674 | 0.999 | 0.860 | 0.501 |

| Uganda–Baseline | Baseline Model I i | Baseline Model II ii | Follow-Up Model I ii | Follow-Up Model II ii |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | How many meals do you think you will cook with the improved cookstove during each week? | Now that you have experienced (ICS brand) how likely is it that you cook all your main meals with that? | How often do you think you will use (ICS brand) in next few months to cook your main meals? | |

| Independent Variable | ||||

| ATB 1: Fuelwood consumption | 0.5541 ** (0.4580) | 1.1833 (0.2765) | 1.3361 (0.6185) | 2.6782 ** (1.2842) |

| ATB 2: Smoke emission | 1.1043 *** (1.0895) | 3.2772 *** (1.2047) | 1.1565 (0.5150) | 2.1335 * (0.9730) |

| SN 1: Support of friends and family | 0.2708 (0.2512) | 1.4703 ** (0.2803) | 0.4525 (0.2513) | |

| SN 2: Importance of opinion of friends and family | 0.4237 ** (0.2734) | 0.5373 * (0.1786) | 0.6441 (0.2007) | |

| SN 3: Importance of neighbors’ stove types | 1.3852 ** (0.2236) | |||

| PBC 1: Obtaining permission or not | 0.6833 *** (0.2579) | 0.7950 (0.2578) | ||

| PBC 2: Power to make decision independently | 0.4619 ** (0.1140) | 0.8986 (0.1341) | 2.5113 *** (0.8898) | |

| PBC 3: Change of habit | 2.7253 *** (0.7831) | |||

| N | 172 | 172 | 87 | 83 |

| Wald chi-squared | 61.01 *** | 24.94 *** | 25.19 *** | 17.98 *** |

| AIC | 309.5 | 343.6 | 190.3 | 103.9 |

| BIC | 340.9 | 368.7 | 212.5 | 120.8 |

| Log pseudo likelihood | −144.7 | −163.8 | −86.17 | −44.95 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pakravan, M.H.; MacCarty, N. What Motivates Behavior Change? Analyzing User Intentions to Adopt Clean Technologies in Low-Resource Settings Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies 2020, 13, 3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13113021

Pakravan MH, MacCarty N. What Motivates Behavior Change? Analyzing User Intentions to Adopt Clean Technologies in Low-Resource Settings Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies. 2020; 13(11):3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13113021

Chicago/Turabian StylePakravan, Mohammad H., and Nordica MacCarty. 2020. "What Motivates Behavior Change? Analyzing User Intentions to Adopt Clean Technologies in Low-Resource Settings Using the Theory of Planned Behavior" Energies 13, no. 11: 3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13113021

APA StylePakravan, M. H., & MacCarty, N. (2020). What Motivates Behavior Change? Analyzing User Intentions to Adopt Clean Technologies in Low-Resource Settings Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Energies, 13(11), 3021. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13113021