Polish Local Government’s Perspective on Revitalisation: A Framework for Future Socially Sustainable Solutions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socially Sustainable Revitalisation

2.2. Revitalisation Policy in Poland

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Assumptions

- RQ1:

- What is the perception of revitalisation objectives among local executive authorities?

- RQ2:

- What factors differentiate the perception of revitalisation objectives by respondents?

- RQ3:

- Does the perception of revitalisation objectives suggest that local policy makers have a holistic approach to the process?

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of the Importance of Revitalisation Objectives—Respondent Perspective

4.2. Factors Differentiating the Perception of Revitalisation Objectives

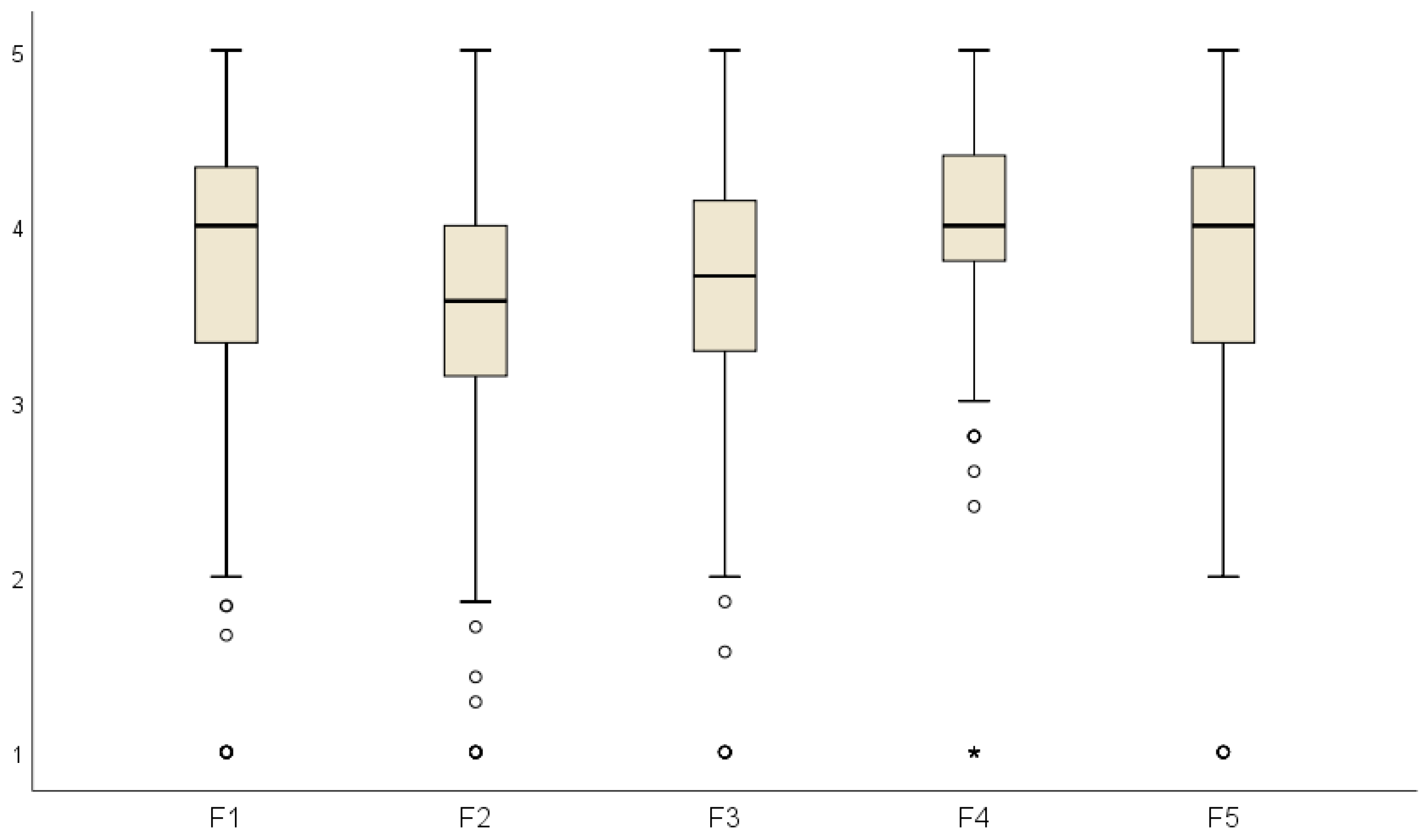

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis: Importance of Revitalisation Objectives

- Factor 1 (F1)—Social inclusion, human and social capital (alfa-Cronbach coefficient 0.889):

- Support to residents threatened with social exclusion (0.906);

- Improve residents’ knowledge, skills, and abilities (0.732);

- Foster community bonds between residents (0.719);

- Resolve social issues in the municipality (0.669);

- Build local partnerships (0.525);

- Integrate activities of different local institutions (0.511).

- Factor 2 (F2)—Local economic development (alfa-Cronbach coefficient 0.804):

- Inflow of new, large companies to the municipality (0.806);

- Improve the performance of public transport (0.654);

- Improve the health status of residents (0.653);

- Inflow of new affluent tenants to refurbished apartments (0.635);

- Support and promotion for local craftsmen and products (0.601);

- Repair roads, pavements, and lighting (0.566; 0.412 for Factor 4);

- Increase the number of businesses within the revitalised area (0.559).

- Factor 3 (F3)—Self-determination and residential satisfaction (alfa-Cronbach coefficient 0.875):

- Increase residents’ engagement in municipal governance (0.801);

- Ensure equal access opportunities to municipal resources for different groups of residents and users (0.748);

- Promote voluntary service among residents (0.664);

- Encourage residents to take care of themselves (0.648);

- Increase residents’ sense of happiness (0.512);

- Improve safety within the revitalised area (0.512);

- Improve the quality of education within the revitalised area (0.454).

- Factor 4 (F4)—Infrastructure (alfa-Cronbach coefficient 0.793):

- Improve technical infrastructure within revitalised area (0.776);

- Improve the aesthetics of the municipal landscape (0.722);

- Improve the technical shape of buildings (0.652);

- Improve social infrastructure within the revitalised area (0.560);

- Improve environmental quality within the revitalised area (0.454).

- Factor 5 (F5)—Shaping public space for residents (alfa-Cronbach coefficient 0.770):

- Develop more higher quality green areas in municipality (0.718);

- Develop public spaces for residents (woonerfs, playgrounds, parks) (0.673);

- Improve infrastructure for leisure-time activities (0.644).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassan, A.M.; Lee, H. The paradox of the sustainable city: Definitions and examples. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1267–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrede, J.; Berg, S.K. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development: The Case of Urban Densification. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2019, 10, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asekomeh, A.; Gershon, O.; Azubuike, S.I. Optimally Clocking the Low Carbon Energy Mile to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from Dundee’s Electric Vehicle Strategy. Energies 2021, 14, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przywojska, J.; Podgórniak-Krzykacz, A. A comprehensive approach: Inclusive, smart and green urban development. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2020, 15, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, P.; Saglie, I.L.; Richardson, T. Urban sustainability: Is densification sufficient? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinawa, Y.; Kouda, Y.; Noda, R. The Resilient Smart City (an Proposal). Selected Papers from TIEMS Annual Conference in Niigata. J. Dis. Res. 2015, 10, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A. Of resilient places: Planning for urban resilience. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steels, S. Key characteristics of age-friendly cities and communities: A review. Cities 2015, 47, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Rémillard-Boilard, S. Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: New Directions for Research and Policy. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Podgórniak-Krzykacz, A.; Przywojska, J.; Wiktorowicz, J. Smart and age-friendly communities in Poland. An analysis of institutional and individual conditions for a new concept of smart development of ageing communities. Energies 2020, 13, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, G.; Morello, E.; Arcidiacono, A. Sharing Cities Shaping Cities. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antuña-Rozado, C.; García-Navarro, J.; Mariño-Drews, J. Facilitation Processes and Skills Supporting EcoCity Development. Energies 2018, 11, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robertson, M. Sustainable Cities. Local Solutions in the Global South; International Development Research Centre: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, G.; Marietta, C.; Tabasso, M.; Eynard, E.; Melis, G. From urban renewal to urban regeneration: Classification criteria for urban interventions. Turin 1995–2015: Evolution of planning tools and approaches. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2016, 7, 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P.; Sykes, H. Urban Regeneration: A Handbook, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T. Urban Geography, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Raco, M. Building Sustainable Communities: Spatial Policy and Labour Mobility in Post-War Britain; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Urban Regeneration: Delivering Social Sustainability. In Urban Regeneration & Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 54–79. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.L.R.; dos Santos Pereira, A.L. Urban Regeneration in the Brazilian urban policy agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardowli, M.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Aram, F.; Mosavi, A. Survey of sustainable regeneration of historic and cultural cores of cities. Energies 2020, 13, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpopi, C.; Manole, C. Integrated Urban Regeneration—Solution for Cities Revitalize. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2013, 6, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keresztély, K.; Scott, J.W. Urban Regeneration in the Post-Socialist Context: Budapest and the Search for a Social Dimension. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1111–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; van Steenbergen, F.; Rok, A.; Roorda, C. Governing sustainability: A dialogue between Local Agenda 21 and transition management. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 939–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, P.; Ferreira, D.C.; Dollery, B.; Marques, R.C. Municipal sustainability influence by european union investment programs on the portuguese local government. Sustainability 2018, 10, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Navarro-Galera, A.; Alcaraz-Quiles, F.J.; Ortiz-Rodriguez, D. Enhancing sustainability transparency in local governments-An empirical research in Europe. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hambleton, R. Leading the Inclusive City: Place-Based Innovation for a Bounded Planet; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akotia, J.; Sackey, E. Understanding socio-economic sustainability drivers of sustainable regeneration: An empirical study of regeneration practitioners in UK. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 2078–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, S.; Malys, N.; Maliene, V.; Malienė, V. Urban regeneration for sustainable communities: A case study. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. Balt. J. Sustain. 2009, 15, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Larsen, K. Can new urbanism infill development contribute to social sustainability? The case of Orlando, Florida. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 3843–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Pajouhesh, P.; Miller, T.R. Social equity in urban resilience planning. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z. An assessment of urban park access in Shanghai—Implications for the social equity in urban China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Power, S. Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2009, 36, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, R.; Ronald, R. The role of urban form in sustainability of community: The case of Amsterdam. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2017, 44, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidfarokhi, A.; Yrjänä, L.; Wallenius, M.; Toivonen, S.; Ekroos, A.; Viitanen, K. Social sustainability tool for assessing land use planning processes. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1269–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T.; Ganser, R.; Carpenter, J.; Ngombe, A. ‘Creating Sustainable Environments’ Measuring Socially Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Europe. 2009. Available online: http://oisd.brookes.ac.uk/sustainable_communities/resources/Social_Sustainability_and_Urban_Regeneration_report.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Colantonio, A. Measuring Social Sustainability: Best Practice from Urban Renewal in the EU 2008/02: EIBURS Working Paper Series Traditional and Emerging Prospects in Social Sustainability. 2008. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Measuring-Social-Sustainability%3A-Best-Practice-from-Colantonio/f755c9a8d879a7862bba63fb38f6712eb4391677 (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Trivellato, B. How can ‘smart’ also be socially sustainable? Insights from the case of Milan. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2017, 24, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, A. Land use challenges, sustainability and the spatial planning balancing act: Insights from Sweden and Switzerland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawasz, D.; Sikora-Fernandez, D. Koncepcja Smart City na tle Procesów i Uwarunkowań Rozwoju Współczesnych Miast; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Urząd Mieszkalnictwa i Rozwoju Miast and GTZ Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit, “Podręcznik Rewitalizacji. Zasady, Procedury i Mechanizmy Działania Współczesnych Procesów Rewitalizacji. Warszawa. 2003. Available online: https://1lib.pl/book/1169022/25a54b?id=1169022&secret=25a54b (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Sagan, I.; Grabkowska, M. Urban Regeneration in Gdańsk, Poland: Local Regimes and Tensions Between Top-Down Strategies and Endogenous Renewal. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1135–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczyca, K.; Kocaj, A.; Fiedeń, Ł. Large housing estates in Poland—A missing link in urban regeneration? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2020–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesiółka, P.; Kudłak, R.; Kołsut, B. Działania rewitalizacyjne w miastach województwa wielkopolskiego w latach 1999–2015 oraz ich efekty. Studia Regionalne i Lokalne 2016, 68, 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjakiewicz, T.; Kudłak, R.; Ciesiółka, P.; Kołsut, B.; Motek, P. Urban regeneration in Poland’s non-core regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 316–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchwała nr 123 Rady Ministrów z Dnia 15 Października 2019 r. w Sprawie Przyjęcia ‘Strategii Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Wsi, Rolnictwa i Rybactwa 2030. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP20190001150 (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Ministry of Infrastructure and Development. Krajowa Polityka Miejska 2023. Warszawa. 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/polityka-miejska (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Ng, M.K. Quality of Life Perceptions and Directions for Urban Regeneration in Hong Kong; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 441–465. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, R. Leading the healthy city: Taking advantage of the power of place. Cities Health 2020, 4, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noworól, A.; Noworól, K. Rewitalizacja obszarów miejskich jako wehikuł rozwoju lokalnego. Stud. Kom. Przestrz. Zagospod. Kraju 2017, 17, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Parysek, J. Rewitalizacja jako problem i zadanie własne polskich samorządów lokalnych. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2016, 33, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Natividade-Jesus, E.; Almeida, A.; Sousa, N.; Coutinho-Rodrigues, J. A Case Study Driven Integrated Methodology to Support Sustainable Urban Regeneration Planning and Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kowalska, M.; Szemik, S. Zdrowie i jakość życia a aktywność zawodowa. Med. Pr. 2016, 67, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kearns, A.; Ghosh, S.; Mason, P.; Egan, M. Urban regeneration and mental health: Investigating the effects of an area-based intervention using a modified intention to treat analysis with alternative outcome measures. Health Place 2020, 61, 102262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Hearty, W.; Taulbut, M.; Mitchell, R.; Dryden, R.; Collins, C. Regeneration and health: A structured, rapid literature review. Public Health 2017, 148, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.G.R.; Laprise, M.; Rey, E. Fostering sustainable urban renewal at the neighborhood scale with a spatial decision support system. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zheng, W.; Hong, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G. Paths and strategies for sustainable urban renewal at the neighbourhood level: A framework for decision-making. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, H.H.; Hu, T.S.; Fan, P. Social sustainability of urban regeneration led by industrial land redevelopment in Taiwan. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1245–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, C. Local experiences of urban sustainability: Researching Housing Market Renewal interventions in three English neighbourhoods. Prog. Plan. 2012, 78, 101–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weingaertner, C.; Barber, A.R.G. Urban regeneration and socio-economic sustainability: A role for established small food outlets. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1653–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, A.; McConnachie, M. Social Exclusion, Urban Regeneration and Economic Reintegration. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 1587–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguipdop-Djomo, P.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Abubakar, I.; Mangtani, P. Small-area level socio-economic deprivation and tuberculosis rates in England: An ecological analysis of tuberculosis notifications between 2008 and 2012. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, G.; Goga, S.; Murphy, F. Local Economic Development: A Primer Developing and Implementing Local Economic Development Strategies and Action Plans; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 33769. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, R.; Hughes, C.; Macdougall, A.; Simpkins, H.G.; Hjelmskog, A. Inclusive Growth in Greater Manchester 2020 and beyond: Taking Stock and Looking forward; University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, M.; Silver, I. Poverty, Partnerships, and Privilege: Elite Institutions and Community Empowerment. City Community 2005, 4, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, K. Społeczny sens rewitalizacji. Ekonomia Społeczna Teksty 2008, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wojnarowska, A.; Kozłowski, S. Rewitalizacja Zdegradowanych Obszarów Miejskich. Zagadnienia Teoretyczne; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dembicka-Niemiec, A.; Drobniak, A.; Szafranek, E. Wpływ projektów rewitalizacyjnych na konkurencyjność gospodarczą na przykładzie gmin województwa opolskiego. Probl. Rozw. Miast 2016, 4, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jadach-Sepioło, A. Rafy procesu rewitalizacji—teoria i polskie doświadczenia. Gospod. Prakt. Teor. 2017, 49, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Dane Statystyczne z Zakresu Rewitalizacji na Poziomie Gmin; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2018.

- Jarczewski, W.; Kułaczkowska, A. Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast. Rewitalizacja; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa-Kraków, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Urban and Regional Development and Ecorys. Badanie Systemu Zarządzania i Wdrażania Procesów Rewitalizacji w Polsce—Ministerstwo Funduszy i Polityki Regionalnej. 2020. Available online: https://www.ewaluacja.gov.pl/strony/badania-i-analizy/wyniki-badan-ewaluacyjnych/badania-ewaluacyjne/badanie-systemu-zarzadzania-i-wdrazania-procesow-rewitalizacji-w-polsce/ (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Brańka, P. Obszary wiejskie w woj. małopolskim o najwyższej koncentracji problemów społeczno-gospodarczych—identyfikacja, czynniki sprawcze—Studia KPZK—PAS Journals Repository. J. PAN 2017, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeżyńska, B. Partnerstwo wiejsko-miejskie jako koncepcja zrównoważonego rozwoju obszarów wiejskich. Teka Kom. Praw.–OL PAN 2018, 1, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kożuch, A. Rewitalizacja a zrównoważony rozwój obszarów wiejskich. Zarządzanie Publiczne Zeszyty Naukowe Instytutu Spraw Publicznych Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego 2010, 1–2, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Czupich, M. Level of Social Participation in the Creation of Urban Regeneration Programmes-The Case Study of Small Towns in Poland. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2018, 25, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Setkowicz, P. Kryzys zaufania. Partycypacja społeczna i podsycanie konfliktów w procesie kształtowania środowiska miejskiego na przykładzie Krakowa. Przestrz. Urban Archit. 2017, 2, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hołuj, D.; Legutko-Kobus, P. A participatory model of creating revitalisation programmes in Poland—Challenges and barriers. Maz. Stud. Reg. 2018, 26, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Masierek, E. Aktualne wyzwania rewitalizacyjne polskich miastna tle ich dotychczasowych doświadczeń. Probl. Rozw. Miast Kwartalnik Nauk. Inst. Rozw. Miast 2016, XIII, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Parysek, J.J. Rewitalizacja miast w Polsce: Wczoraj, dziś i być może jutro. Stud. Miej. 2015, 17, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesiółka, P. Rewitalizacja w polityce rozwoju kraju. Rozw. Regionalny Polityka Regionalna 2017, 39, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dorota, B. Rewitalizacja jako obszar współpracy międzysektorowej. Rocz. Lubuski 2017, 43, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Leszkowicz-Baczyński, J. Ewolucja Działań Rewitalizacyjnych w Polsce. Przegląd Problematyki. Rocz. Lubuski 2019, 45, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski, M. Rewitalizacja a spójność lokalna. Rola ekonomii społecznej. Stud. Reg. Lokal. 2021, 22, 60–83. [Google Scholar]

| Municipality | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Urban municipality (UM) | 113 | 19.7 |

| City with a county status (CCS) | 39 | 6.8 |

| Urban-rural municipality (URM) | 184 | 32.1 |

| Rural municipality (RM) | 230 | 40.2 |

| No data | 7 | 1.2 |

| Total | 573 | 100.0 |

| Revitalisation Objective | Total Population | Mean (M) by Type of Municipality | p | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | STD | Q1 | Me | Q3 | UM | CCS | URM | RM | ||

| Improve technical infrastructure within the revitalised area | 512 | 4.20 | 0.814 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.31 | 3.96 | 4.20 | 4.18 | 0.213 |

| Resolve social problems in the municipality | 516 | 4.17 | 0.893 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.40 | 4.57 | 4.10 | 4.06 | 0.001 * |

| Assist residents threatened with social exclusion | 530 | 4.16 | 0.951 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.30 | 4.57 | 4.15 | 4.05 | 0.014 * |

| Improve social infrastructure within the revitalised area | 509 | 4.16 | 0.810 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.34 | 4.21 | 4.18 | 4.06 | 0.040 * |

| Improve the aesthetics of municipality landscape | 504 | 4.15 | 0.737 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.20 | 4.17 | 4.18 | 4.11 | 0.716 |

| Develop public spaces for residents, such as woonerfs, playgrounds, or parks | 510 | 4.13 | 0.853 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.12 | 4.31 | 4.17 | 4.06 | 0.370 |

| Repair roads, pavements, and lighting | 533 | 4.00 | 1.096 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3.72 | 3.37 | 3.97 | 4.21 | <0.001 * |

| Improve safety within the revitalised area | 501 | 3.97 | 0.854 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.10 | 4.07 | 4.05 | 3.82 | 0.014 * |

| Improve technical shape of buildings | 506 | 3.96 | 0.844 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4.00 | 3.97 | 3.98 | 3.92 | 0.871 |

| Improve infrastructure for leisure-time activities | 507 | 3.94 | 0.848 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3.97 | 3.97 | 4.06 | 3.83 | 0.075 |

| Encourage residents to take care of themselves and their neighbourhood | 496 | 3.90 | 0.916 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3.99 | 4.34 | 3.89 | 3.80 | 0.002 * |

| Improve environmental quality at the revitalised area | 491 | 3.86 | 0.830 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.95 | 3.89 | 3.91 | 3.79 | 0.386 |

| Foster community bonds between residents | 498 | 3.81 | 0.928 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.97 | 4.30 | 3.71 | 3.75 | 0.003 * |

| Increase the population of businesses within the revitalised area | 485 | 3.81 | 0.948 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.86 | 4.00 | 3.85 | 3.74 | 0.355 |

| Ensure equal access to municipal resources to different groups of residents and users | 492 | 3.71 | 0.912 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.89 | 3.97 | 3.69 | 3.58 | 0.017 * |

| Improve the quality of education within the revitalised area | 495 | 3.70 | 0.958 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.67 | 3.57 | 3.77 | 3.68 | 0.687 |

| Improve knowledge, skills, and abilities of local residents | 492 | 3.64 | 0.936 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.61 | 3.97 | 3.65 | 3.58 | 0.158 |

| Attract new, large companies to the municipality | 488 | 3.62 | 1.071 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.57 | 3.60 | 3.78 | 3.53 | 0.172 |

| Increase the residents’ sense of happiness | 483 | 3.60 | 0.942 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.61 | 3.76 | 3.67 | 3.52 | 0.390 |

| Integrate the activities of different local institutions | 487 | 3.57 | 0.890 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.63 | 4.07 | 3.58 | 3.45 | <0.001 * |

| Improve health status of residents | 481 | 3.56 | 0.938 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.46 | 3.50 | 3.70 | 3.50 | 0.100 |

| Develop more higher quality green areas in the municipality | 487 | 3.54 | 0.885 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.67 | 3.72 | 3.69 | 3.33 | <0.001 * |

| Build local partnerships | 491 | 3.52 | 0.924 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.67 | 4.03 | 3.52 | 3.37 | 0.001 * |

| Support and promote local craftsmen and products | 483 | 3.48 | 0.960 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.44 | 3.64 | 3.58 | 3.38 | 0.199 |

| Increase residents’ engagement in municipal governance | 480 | 3.46 | 0.929 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.62 | 3.63 | 3.49 | 3.33 | 0.056 |

| Improve the performance of public transport | 481 | 3.30 | 1.030 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3.33 | 3.43 | 3.37 | 3.21 | 0.410 |

| Promote voluntary service among residents | 481 | 3.21 | 0.930 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3.27 | 3.48 | 3.32 | 3.07 | 0.023 * |

| Inflow of new, affluent tenants to refurbished apartments | 478 | 2.83 | 1.098 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2.95 | 2.89 | 3.00 | 2.64 | 0.015 * |

| Indicator | n | Mean | STD | Q1 | Me | Q3 | Urban Municipality | City with County Status | Urban-Rural Municipality | Rural Municipality | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social inclusion, human and social capital | 462 | 3.80 | 0.736 | 3.33 | 4.00 | 4.33 | 3.95 | 4.24 | 3.76 | 3.69 | <0.001 * |

| Local economic development | 455 | 3.49 | 0.724 | 3.14 | 3.57 | 4.00 | 3.48 | 3.51 | 3.58 | 3.42 | 0.220 |

| Self-determination and residential satisfaction | 459 | 3.64 | 0.687 | 3.29 | 3.71 | 4.00 | 3.73 | 3.80 | 3.68 | 3.54 | 0.065 |

| Infrastructure | 466 | 4.05 | 0.587 | 3.80 | 4.00 | 4.40 | 4.13 | 4.02 | 4.07 | 3.99 | 0.286 |

| Shaping public space for residents | 477 | 3.85 | 0.712 | 3.33 | 4.00 | 4.33 | 3.92 | 4.00 | 3.95 | 3.70 | 0.002 * |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | rho | 1 | 0.402 | 0.667 | 0.283 | 0.435 |

| p | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | ||

| Factor 2 | rho | 0.402 | 1 | 0.557 | 0.418 | 0.386 |

| p | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | ||

| Factor 3 | rho | 0.667 | 0.557 | 1 | 0.425 | 0.471 |

| p | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | ||

| Factor 4 | rho | 0.283 | 0.418 | 0.425 | 1 | 0.369 |

| p | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | ||

| Factor 5 | rho | 0.435 | 0.386 | 0.471 | 0.369 | 1 |

| p | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przywojska, J. Polish Local Government’s Perspective on Revitalisation: A Framework for Future Socially Sustainable Solutions. Energies 2021, 14, 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14164888

Przywojska J. Polish Local Government’s Perspective on Revitalisation: A Framework for Future Socially Sustainable Solutions. Energies. 2021; 14(16):4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14164888

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzywojska, Justyna. 2021. "Polish Local Government’s Perspective on Revitalisation: A Framework for Future Socially Sustainable Solutions" Energies 14, no. 16: 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14164888