The Costs and Trade-Offs of Green Central Banking: A Framework for Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Critical Literature Review and Research Objectives

2.1. Literature Review: Disregarding the Costs of Going Green

2.2. The Popular-Press Case for Considering the Costs and Trade-Offs of Going Green

2.3. Research Objectives

3. Overview of the Research Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. TheAnalytical Framework

4.1.1. The Template of Modern Central Banking

4.1.2. The Implications of the Green Proposal for the Central Banking Framework

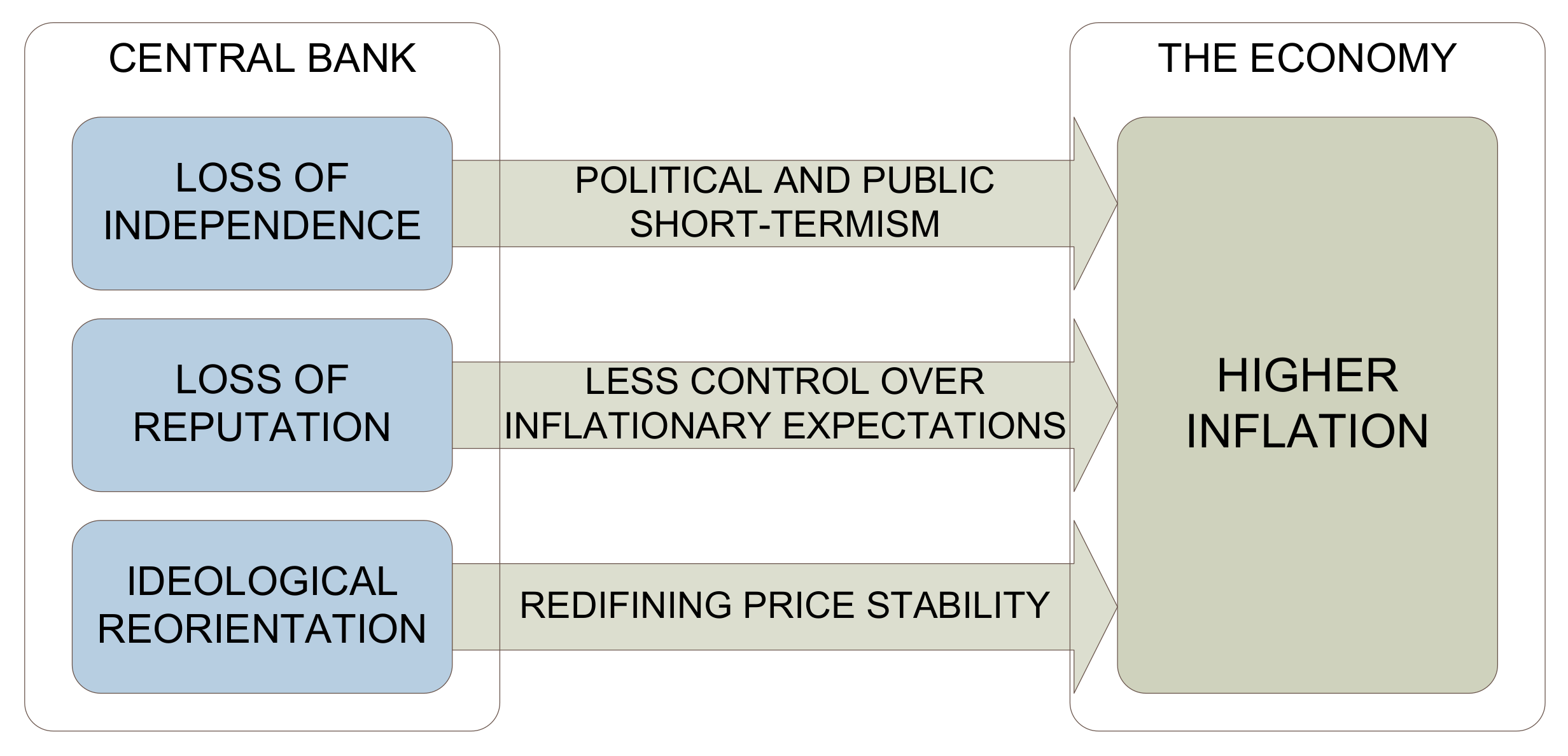

4.1.3. A Taxonomy of Costs and Trade-Offs of Green Central Banking

4.2. Case Studies

4.2.1. The Euro Area

4.2.2. Brazil

4.2.3. Romania

5. Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, P.; Alexander, K. Climate Change: The Role for Central Banks. Data Analytics for Finance Macro Research Centre; Working Paper No. 2019/6; King’s College London: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gunningham, N.A. Quiet revolution: Central banks, financial regulators, and climate finance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, U. On the role of central banks in enhancing green finance. In Design of a Sustainable Financial System; Inquiry Working Paper 17/01; UNEP, Inquiry: Nairobi, Kenya, February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campiglio, E. Beyond carbon pricing: The role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Lerven, F.; Ryan-Collins, J. Central Banks, Climate Change and the Transition to a Low Carbon Economy: A Policy Briefing; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/NEF_BRIEFING_CENTRAL-BANKS-CLIMATE_E.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Barmes, D.; Livingstone, Z. The Green Central banking scorecard: How green are G20 central banks and financial supervisors? Positive Money: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://positivemoney.org/publications/green-central-banking-scorecard (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Grippa, P.; Schmittmann, J.; Suntheim, F. Climate change and financial risk. Fin. Dev. 2019, 56, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- The Impact of Climate Change on the UK Insurance Sector. A Climate Change Adaptation Report by the Prudential Regulation Authority; Bank of England: London, UK, 2015.

- Schoenmaker, D.; Tilburg, R.V. What role for financial supervisors in addressing environmental risks? Comp. Econ. Stud. 2016, 58, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macquarie, R.A.; Green Bank of England. Central banking for a low-carbon economy. Posit. Money 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/3e0E4Cb (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Bolton, P.; Despress, M.; da Silva, L.A.P.; Samama, F.; Svartzman, R. The Green Swan—Central Banking and Financial Stability in the Age of Climate Change, Bank for International Settlements.Banque de France Eurosystème. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/3vtzNgj (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Dikau, S.; Volz, U. Central bank mandates, sustainability objectives and the promotion of green finance. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 184, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.; Campiglio, E.; Deyris, J. It Takes Two to Dance: Institutional Dynamics and Climate-Related Financial Policies. 2021. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3862256 (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Monnin, P. Central banks and the transition to a low-carbon economy. Counc. Econ. Policies Discuss. Note 2018, 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiglio, E.; Dafermos, Y.; Monnin, P.; Ryan-Collins, J.; Schotten, G.; Tanaka, M. Finance and climate change: What role for central banks and financial regulators. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, D. Greening monetary policy. Clim. Pol. 2021, 21, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikau, S.; Volz, U. Central Banking, Climate Change and Green Finance; ADBI Working Paper Series No. 867; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Orazio, P.; Popoyan, L. Taking up the Climate Change Challenge: A New Perspective on Central Banking; LEM Working Paper Series, No. 2020/19; ScuolaSuperioreSant’Anna; Laboratory of Economics and Management (LEM): Pisa, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, P.; Morris, J.H. Central banks: Climate governors of last resort? EPA Econ. Space 2020, 52, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikau, S.; Ryan-Collins, J. Green Central Banking in Emerging Market and Developing Country Economies; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2017; Available online: http://neweconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Green-Central-Banking.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Honohan, P. Should Monetary Policy Take Inequality and Climate Change into Account; Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- NGFS, Annual Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/ngfs_annual_report_2020.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Blyth, M.; Lonergan, E. Print less but transfer more: Why central banks should give money directly to the people. Foreign Aff. 2014, 93, 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dietsch, P.; Claveau, F.; Fontan, C. Do Central Banks Serve the People? Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, G. Central Banks as Agents of Economic Development; WIDER Research Paper: 2006. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/63574 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Dafe, F.; Volz, U. Financing Global Development: The Role of Central Banks; Briefing Paper; German Development Institute/Deutsches Institutfür Entwicklungspolitik (DIE): Bonn, Germany, 2015; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Politi, J. Joe Biden vows to push Fed on economic racial inequality. Financial Times, 28 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Green envy. The rights and wrongs of central-bank greenery. The Economist, 14 December 2019.

- Gross, D. The Dangerous Allure of Green Central Banking, Project Syndicate. 18 December 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/2PytXuS (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Brunnermeier, M.K.; Landau, J.-P. Central banks and climate change. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/central-banks-and-climate-change (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Cochrane, J.H. Central Banks and Climate: A Case of Mission Creep; Hoover Institution: Stanford, CA, USA, 13 November 2020; Available online: https://www.hoover.org/research/central-banks-and-climate-case-mission-creep (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Cochrane, J.H. Challenges for Central Banks. Available online: https://johnhcochrane.blogspot.com/2020/10/challenges-for-central-banks.html (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Salter, A.W.; Smith, D.J. End the Fed’s Mission Creep. Wall Street Journal. 25 March 2021. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/end-the-feds-mission-creep-11616710463 (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Ozili, P.K. Managing climate change risk: A responsibility for politicians not Central Banks. InNew Challenges for Future Sustainability and Wellbeing; Özen, E., Grima, S., Gonzi, R.E.D., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.; Rojon, C. On the attributes of a critical literature review. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Prac. 2011, 4, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanley, L. The difference between an analytical framework and a theoretical claim: A reply to Martin Carstensen. Pol. Stud. 2012, 60, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.H. The Theory of Monetary Institutions; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, P. Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M.; Goodhart, C.A.E. Money, Inflation and the Constitutional Position of the Central Bank; Institute of Economic Affairs: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- White, L.H. The rule of law or the rule of central bankers. Cato J. 2010, 30, 451–463. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, W.A. Implementing Monetary Policy; Centre for Central Banking Studies, Bank of England: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blinder, A.S. Central Banking in Theory and Practice; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, D.J. A coming crisis of legitimacy? Sver. Riksbank Econ. Rev. 2016, 3, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dietsch, P. Legitimacy Challenges to Central Banks: Sketching a Way Forward, Council on Economic Policies Discussion Note 02. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/3ss6ESx (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Binder, C. De facto and de jure central bank independence. In Populism, Economic Policies and Central Banking; Gnan, E., Masciandaro, D., Eds.; Bocconi University and BAFFI CAREFIN: Wien, Austria, 2020; pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tortola, P.D. The Politicization of the European Central Bank: What Is It, and How to Study It? JCMS 2020, 58, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rogoff, K. The optimal degree of commitment to an intermediate monetary target. Quart. J. Econ. 1985, 100, 1169–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J. Rethinking central bank accountability in uncertain times. Ethics Int. Aff. 2016, 30, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blinder, A.S. Central-bank credibility: Why do we care? How do we build it? Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernanke, B.S. Monetary Policy and Inequality, Brookings. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2015/06/01/monetary-policy-and-inequality/ (accessed on 1 June 2015).

- Hülsmann, J.G. Fiat money and the distribution of incomes and wealth. In The Fed at One Hundred. A Critical View on the Federal Reserve System; Howden, D., Salerno, J.T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing Switzerland: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Cœuré, B. Embarking on Public Sector Asset Purchases, Speech Given at the Second International Conference on Sovereign Bond Markets, Frankfurt. 10 March 2015. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2015/html/sp150310_1.en.html. (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Kane, E.J. Good intentions and unintended evil: The case against selective credit allocation. J. Money Credit Bank. 1977, 9, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volokh, E. The mechanisms of the slippery slope. Harv. Law Rev. 2003, 116, 1026–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, I.; Uegaki, A. Central bank independence and inflation in transition economies: A comparative meta-analysis with developed and developing economies. East. Eur. Econ. 2017, 55, 197–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kokoszczyński, R.; Mackiewicz-Łyziak, J. Central bank independence and inflation—Old story told anew. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 25, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagus, P. The ZIRP trap—The institutionalization of negative real interest rates. Procesos Merc. Rev. Eur. Econ. Política 2015, 12, 105–164. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. Comments on monetary policy. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1951, 33, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groepe, F. The Changing Role of Central Banks, Speech given at the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. Available online: https://www.bis.org/review/r160818a.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2016).

- Mersch, I. Financial Stability and the ECB, Speech Given at the ESCB Legal Conference, Frankfurt a. M. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2018/html/ecb.sp180906.en.html (accessed on 6 September 2018).

- Schnabel, I. When Markets Fail—The Need for Collective Action in Tackling Climate Change, Speech Given at the European Sustainable Finance Summit, Frankfurt a. M. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2020/html/ecb.sp200928_1~268b0b672f.en.html (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Schnabel, I. From Market Neutrality to Market Efficiency, Speech Given at the ECB DG-Research Symposium Climate Change, Financial Markets and Green Growth, Frankfurt a. M. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2021/html/ecb.sp210614~162bd7c253.en.html (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Schnabel, I. Never Waste a Crisis: COVID-19, Climate Change and Monetary Policy, Speech Given at a Virtual Roundtable on Sustainable Crisis Responses in Europe Organized by the INSPIRE Research Network, Frankfurt a. M. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2020/html/ecb.sp200717~1556b0f988.en.html (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Feldstein, M. EMU and international conflict. For. Aff. 1997, 76, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagus, P. The Tragedy of the Euro; Ludwig von Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tesche, T. Instrumentalizing EMU’s democratic deficit: The ECB’s unconventional accountability measures during the eurozone crisis. J. Eur. Integr. 2019, 41, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Brazil. National Monetary Council. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/about/cmnen (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Law No. 4,595/31 December 1964 on the National Financial System. Available online: https://bit.ly/3zqFg9K (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Central Bank of Brazil. Inflation Targeting. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/monetarypolicy/Inflationtargeting (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Dall’Orto Mas, R.; Vonessen, B.; Fehlker, C.; Arnold, K. The Case for Central Bank Independence: A Review of Key Issues in the International Debate, ECB Occasional Paper, No. 248, European Central Bank, Frankfurt a. M. 2020. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/234489/1/ecb-op248.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Araújo, E.; Arestis, P. Lessons from the 20 years of the Brazilian inflation targeting regime. Panoeconomicus 2019, 66, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Central Bank of Brazil. Social and Environmental Responsibility. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/about/socialresponsibility (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Mello, L. Climate Bonds & Banco Central do Brasil Sign Agreement to Develop Sustainable Finance Agenda: New partnership to share technical knowledge on climate & financial sector, Climate Bonds Blog. Available online: https://bit.ly/3xYGkBt (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Central Bank of Brazil. Sustainability. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/financialstability/sustainability (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Caminha, M. Brazilian Central Bank opens public consultation on sustainability criteria applicable to rural credit, Climate Bonds Blog. 30 March 2021. Available online: https://bit.ly/2UER9Kn (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Law No. 312/28 June 2004 on the Statute of the National Bank of Romania, Monitorul Oficial al României, Part I, No. 582. Available online: https://www.bnro.ro/files/d/Legislatie/Lege_statut_bnr/L_StatBNR.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- National Bank of Romania. Direct Inflation Targeting. Available online: https://www.bnr.ro/Direct-Inflation-Targeting-3646.aspx (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Isărescu, M. Towards a Green and Smart Economy in Romania. Speech given at the EIB seminar Investment and Investment Finance in Romania, 25 February 2021. Available online: https://bit.ly/3rhbIsl (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. To Green or not to Green? Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/themes/green-recovery (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- National Bank of Romania. Financial Stability Report. June 2020. Available online: https://bnro.ro/DocumentInformation.aspx?idDocument=35334&idInfoClass=19968 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- National Bank of Romania. Inflation Report. May 2021. Available online: https://bnro.ro/DocumentInformation.aspx?idDocument=37236&idInfoClass=6876 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- National Committee for Macroprudential Oversight. Report of the Working Group on Green Finance. Available online: http://www.cnsmro.ro/res/ups/Raport-CNSM-pentru-sprijinirea-finantarii-verzi_PUB.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021). (In Romanian).

- Albulescu, C.T.; Oros, C.; Tiwari, A.K. Oil price–inflation pass-through in Romania during the inflation targeting regime. Appl. Econ. 2017, 49, 1527–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levieuge, G.; Lucotte, Y.; Ringuedé, S. Central bank credibility and the expectations channel: Evidence based on a new credibility index. Rev. World Econ. 2018, 154, 493–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Limited Mandate | Independence | Indirect Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Clear goals | Accountability | Short-term interest rate adjustments |

| Stable goals | Transparency | No state deficit financing |

| Legitimacy | Limited discretion | No credit controls |

| Credibility | No interest rate controls | |

| Reputation |

| Going Green | Acting Green | Staying Green |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of legitimacy | Price instability | Excessive reliance on monetary policy |

| Loss of independence | Loss of reputation | Green central bank conservatism |

| Politicization | Distributional effects | “Ideas have consequences” |

| Mission creep | Less countercyclical capacity | |

| Slippery slope |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Șimandan, R.; Păun, C. The Costs and Trade-Offs of Green Central Banking: A Framework for Analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14165168

Șimandan R, Păun C. The Costs and Trade-Offs of Green Central Banking: A Framework for Analysis. Energies. 2021; 14(16):5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14165168

Chicago/Turabian StyleȘimandan, Radu, and Cristian Păun. 2021. "The Costs and Trade-Offs of Green Central Banking: A Framework for Analysis" Energies 14, no. 16: 5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14165168

APA StyleȘimandan, R., & Păun, C. (2021). The Costs and Trade-Offs of Green Central Banking: A Framework for Analysis. Energies, 14(16), 5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14165168