The Energy Landscape versus the Farming Landscape: The Immortal Era of Coal?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

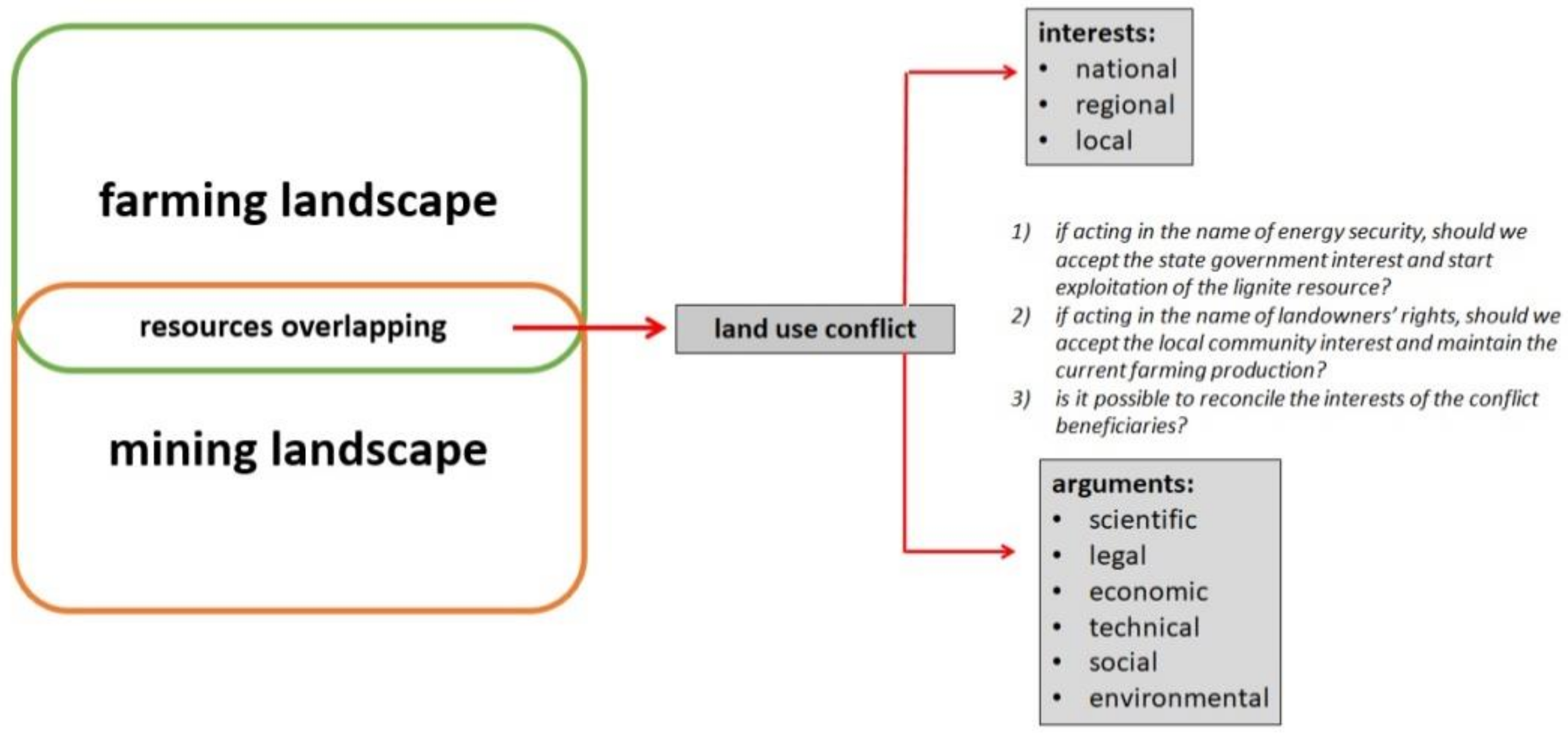

1.1. Introduction to Conflicts over Mining and Farming Land Use

1.2. Conflict over Mining and Farming Land Use—The Literature Overview

1.3. Contribution to Conflicts over Mining and Farming Land Use

2. The Methodological Context of Analysis

2.1. How the Methodological Framework Was Developed

2.2. How the Conflict over Farming and Mining Land Use Was Analysed

2.3. Case Study

3. Facts and Findings

3.1. The Licence for Deposit Exploration and Investigation

3.2. The Licence to Mine the Deposit

3.3. The Water Issue and Local and Regional Development

3.4. Social Injustice

4. General Discussion

4.1. Mining Context

4.2. Farming Context

5. Limitations and Prospects for Resolution of Land Use Conflict

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karasmanaki, E.; Ioannou, K.; Katsaounis, K.; Tsantopoulos, G. The attitude of the local community towards investments in lignite before transitioning to the post-lignite era: The case of Western Macedonia, Greece. Resour. Policy 2020, 68, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euracoal. Available online: https://euracoal.eu/info/euracoal-eu-statistics/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Kasztelewicz, Z.; Ptak, M.; Sikora, M. Węgiel brunatny optymalnym surowcem energetycznym dla Polski. Zesz. Nauk. Instyt. Gospod. Sur. Mineral. Energią PAN 2018, 106, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Program for the Lignite Mining Sector in Poland; The Ministry of Energy: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/9cf46169-01a5-492a-b6c4-98c06713a45e (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Delina, L.L. Topographies of coal mining dissent: Power, Politics, and protests in southern Philippines. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worlanyo, A.S.; Jiangfeng, L. Evaluating the environmental and economic impact of mining for post-mined land restoration and land-use: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C.R. Methods for identifying land use conflict potential using participatory mapping. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 122, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graybill, J.K. Mapping an emotional topography of an ecological homeland: The case of Sakhalin Island, Russia. Emot. Space, Soc. 2013, 8, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.; Jeanneaux, P. Two approaches for understanding land-use conflict to improve rural planning and management. J. Rural Community Dev. 2009, 4, 118–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lumerman, P.; Psathakis, J.; Ortiz, M. Climate Change Impacts on Socio-Environmental Conflicts: Diagnosis and Challenges of the Argentinean Situation; Initiative for Peacebuilding: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrmann, B. Land Conflicts: A Practical Guide to Dealing with Land Disputes, GTZ; Land Management: Eschborn, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nolon, S.; Ferguson, O.; Field, P. Land in Conflict: Managing and Resolving Land Use Disputes; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.M.; Fischer, A.; Marshall, K.; Travis, J.M.; Webb, T.J.; Di Falco, S.; Van der Wal, R. Developing an integrated conceptual framework to understand biodiversity conflicts. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Melot, R.; Mags, H.; Bossuet, L.; Cadoret, A.; Caron, A.; Darly, S.; Jeanneaux, F.; Kirat, T.; Vu Pham, H.; et al. Identifying and measuring land-use and proximity conflicts: Methods and identification. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Petrescu, D.C.; Azadi, H.; Petrescu-Mag, I.V. Agricultural land use conflict management—Vulnerabilities, law restrictions and negotiation frames. A wake-up call. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, R.M.; Witt, G.B.; Lacey, J. Strange bedfellows or an aligning of values? Exploration of stakeholder values in an alliance of concerned citizens against coal seam gas mining. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. An overview of land use conflicts in mining communities. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. Measurement and prediction of land use conflict in an opencast mining area. Resour. Policy 2021, 71, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svobodova, K.; Owen, J.R.; Lebre, E.; Edraki, M.; Littleboy, A. The multi-risk vulnerability of global coal regions in the context of mine closure. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Mine Closure, Perth, Australian, 3–5 September 2019; pp. 553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Kivien, S.; Kotilainen, J.; Kumpula, T. Mining conflicts in the European Union: Environmental and political perspectives. Fennia 2020, 198, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markuszewska, I. Funkcjonowanie oraz zagospodarowanie obszarów poprzemysłowych związanych z eksploatacją surowców ilastych ceramiki budowlanej. Prace Kom. Kraj. Kult. 2007, 6, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Stepans, R. A case for rancher-environmentalist coalitions in coal bed methane litigation: Preservation of unique values in an evolving landscape. Wyo. Law Rev. 2008, 8, 449–480. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M.I.; Hine, D.W.; Bhullar, N.; Dunstan, D.A.; Bartik, W. Fracked: Coal seam gas extraction and farmers’ mental health. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.; Pohja-Mykrä, M.; Lähdesmäki, M.; Kurki, S. “I feel it is mine!”—Psychological ownership in relation to natural resources. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bloodworth, A.J.; Scott, P.W.; McEvoy, F.M. Digging the backyard: Mining and quarrying in the UK and their impact on future land use. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bustos, B.; Folchi, M.; Fragkou, M. Coal mining on pastureland in Southern Chile; challenging recognition and participation as guarantees for environmental justice. Geoforum 2017, 84, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Zhang, A. The paths to social licence to operate: An integrative model explaining community acceptance of mining. Resour. Policy 2014, 39, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercer-Mapstone, L.; Rifkin, W.; Louis, W.R.; Moffat, K. Company-community dialogue builds relationships, fairness, and trust leading to social acceptance of Australian mining developments. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Widana, A. The Impacts of Mining Industry. Socio-Econ. Political Impacts 2019, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hajkowicz, S.A.; Heyenga, S.; Moffat, K. The relationship between mining and socio-economic well-being in Australia’s regions. Resour. Policy 2011, 36, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, L.G. Surface Coal Mining and Human Health: Evidence from West Virginia. South. Econ. J. 2018, 84, 1109–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Ju, Y. Public participation in NIMBY risk mitigation: A discourse zoning approach in the Chinese context. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, D.; Gorman, D.; Chapelle, B.; Mann, W.; Saal, R.; Penton, G. Impact of the mining industry on the mental health of landholders and rural communities in southwest Queensland. Australas. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Cooke, S.J.; Lesser, P.; Macura, B.; Nilsson, N.E.; Taylor, J.J.; Raito, K. Evidence of the impact of mental mining and the effectiveness of mining mitigation measures on social-ecological systems in Artic and Arboreal regions; a systematic map protocol. Environ. Evid. 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markuszewska, I. ‘Old trees cannot be replanted’: When energy investment meets farmers’ resistance. J. Settl. Spat. Plan 2021, 8, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prno, J. An analysis of factors leading to establishment of a social license to operate in the mining industry. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, L.; Umander, K.; Leneisja, J. Social license to operate in the frame of social capital exploring local acceptance of mining in two rural municipalities in the European North. Resour. Policy 2019, 64, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, T.L.; Matlaba, V.J.; Mota, J.A.; dos Santos, J.F. Measuring the social license to operate of the mining industry in an Amazonian town: A case study of Canaã dos Carajás, Brazil. Miner. Econ. 2019, 32, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, R.G.; Thomson, I. Modelling and measuring the social license to operate: Fruits of a dialogue between theory and practice. In Proceedings of the International Mine Management Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 20–21 November 2012; Available online: http://socialicense.com/publications.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Dominy, M.D. Calling the Station Home: Place and Identity in New Zealand’s High Country; Rowman and Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hildenbrand, B.; Hennon, C. Above all, farming means family farming. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2005, 36, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C.M. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.B. Attachment to the ordinary landscape. In Place Attachment, 1st ed.; Altman, I., Low, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.I.; Ryan, R.L. Place attachment and landscape preservation in rural New England: A Maine case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R. Sense of place in development context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, G. My decision to sell the family farm. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuaig, J.M.; Quinn, M.S. Place-based environmental governance in the Waterton Biosphere Reserve, Canada: The role of a large private land trust project. George Wright Forum 2011, 28, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M. Symbolic ties that bind: Place attachment in the plaza. In Place Attachment, 1st ed.; Altman, I., Low, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, R. Mining memories in a rural community: Landscape, temporality and place identity. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 36, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J.C.; Portela, J.; Pinto, P.A. A social approach to land consolidation schemes. A Portuguese case study: The Valenca Project. Land Use Policy 1996, 13, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezińska, A.W.; Machowska, M. Etnografowie na Biskupiźnie. In Biskupizna: Ziemia—Tradycja—Tożsamość; Brzezińska, A.W., Machowska, M., Eds.; Gminne Centrum Kultury i Rekreacji: Krobia, Poland, 2016; pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hummon, D. Community attachment, local sentiment and sense of place. In Place Attachment, 1st ed.; Altman, I., Low, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Palang, H.; Helmfrid, S.; Antrop, M.; Alumäe, H. Rural Landscapes: Past processes and future strategies. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, B.; Smith, T.; Jacobson, C. Love of the land: Social-ecological connectivity of rural landholders. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 51, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frantál, B. Living on coal: Mined-out identity, community displacement and forming of anti-coal resistance in the most region, Czech Republic. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Murphy, C.; Lorenzoni, I. Place attachment, disruption and transformative adaptation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, S.A. Mining-induced displacement and resettlement: The case of rutile mining communities in Sierra Leone. J. Sustain. Min. 2019, 18, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Li, Y.; Hay, I.; Zou, X.; Tu, X.; Wang, B. Beyond Place Attachment: Land Attachment of Resettled Farmers in Jiangsu. China Sustain. 2019, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preston, S.; Gelman, S. This land is my land: Psychological ownership increases willingness to protect the natural world more than legal ownership. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bec, A.; Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.J. Drilling into community perceptions of coal seam gas in Roma. Australia. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.; Ho, P. Is mining harmful or beneficial? A survey of local community perspectives in China. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Hodge, P. To be transformed: Emotions in cross-cultural, field-based learning in Northern Australia. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2012, 36, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuk, E. Geologiczne podstawy dla nowego złoża węgla brunatnego w strefie rowu tektonicznego Poznań—Czempiń—Gostyń. Przegl. Geol. 1978, 26, 588–594. [Google Scholar]

- Urbański, P. Węgiel brunatny systemu Rowów Poznańskich jako gwarancja bezpieczeństwa energetycznego Polski. Biul. PIG 2018, 472, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, K. Węgiel brunatny zagrożeniem dla przyszłości Wielkopolski. Przegl. Komunal. 2015, 1, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejczak, A. Rolnictwo czy węgiel brunatny—utylitarność zasobów w rozwoju lokalnym gminy Krobi. Stud. Obszar. Wiej. 2016, 44, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local Database. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Przybyłek, J.; Górski, J. Złoże węgla brunatnego Oczkowice—głos za właściwym rozpoznaniem hydrogeologicznym. Przegl. Geol. 2016, 64, 168–191. [Google Scholar]

- Parliamentary Question K7INT30539/2015. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question DKG-VIII-4741-8224/102/51211/14/MW. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question K7INT34526/2015. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Act on 9 June 2011 on Geological and Mining Law. J. Laws 2011, As Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20111630981/U/D20110981Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Act on 2 July 2004 on Liberty of Economic Activity. J. Laws 2004, As Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20041731807/U/D20041807Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question K6INT1296/2012. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question K7INT33276/2015. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question K8INT5253/2016. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question BPS/043-22-896-MŚ/12. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question K8INT4150/2015. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Act on 27 March 2003 on Spatial Planning and Development. J. Laws 2003, As Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20030800717/U/D20030717Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Act on 3 October 2008 on the Provision of Information on the Environment and its Protection, Public Participation in Environmental Protection and Environmental Impact Assessments. J. Laws 2008, As Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20081991227/U/D20081227Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Regulation of the Council of Ministers on 10 September 2019 on Projects that May Significantly Affect the Environment. J. Laws 2019. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20190001839/O/D20191839.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Przybyłek, J.; Dąbrowski, S. Planowana kopalnia odkrywkowa na złożu węgla brunatnego „Oczkowice” zagrożeniem dla gospodarki wodnej i środowiska południowo-zachodniej Wielkopolski. Przegl. Geol. 2017, 65, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar]

- The Regulation of the Minister of the Environment on 8 May 2014 on Hydrogeological Documentation and Geological-Engineering Documentation. J. Laws 2014. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20140000596/O/D20140596.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Code of Administrative Law on 14 June 1960. J. Laws 1960, As Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19600300168/U/D19600168Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Meeting of the Environment Committee (117th) on 3 March 2015. In Lignite in South-Western Wielkopolska—Expected Causes of Opencast Mining; Senate of the Republic of Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2015.

- Wielkopolska 2020. Updated Development Strategy of the Wielkopolska Province by 2020, 2012, Poznań. Available online: https://wrpo.wielkopolskie.pl/system/file_resource_archives/attachments/000/000/404/original/Zaktualizowana_Strategia_RWW_do_2020.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Resolution No. V/70/19 of the Government of the Wielkopolskie Province, on 25 March 2019 on the Adoption of the Spatial Development Plan for the Wielkopolskie Province Together with the Spatial Development Plan of the Functional Urban Area of Poznań. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwj3w5S04OXzAhWVnosKHZCZBhEQFnoECAsQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fbip.umww.pl%2Fartykuly%2F2824952%2Fpliki%2F20190328121632_70.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0jWVIcqz2L-QG81d9DJwST (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- The Act on 10 May 2018 Supporting New Investments. J. Laws 2018, As Amended. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20180001162/U/D20181162Lj.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- White Book of the Protection of Mineral Deposits; Ministerstwo Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwicoIS84eXzAhWwxIsKHQBpD3YQFnoECAIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Finfolupki.pgi.gov.pl%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fczytelnia_pliki%2F1%2Fbiala_ksiega_zloz_kopalin.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2zCJbT2rGlgsa0-laipB7r (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question K7ZAP950/2015. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Parliamentary Question K7ZA308580/2015. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp/page=12 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Epstein, P.R.; Buonocore, J.J.; Eckerle, K.; Hendry, M.; Stout, B.M.; Heinberg, R.; Clapp, R.W.; May, B.; Reinhart, N.L.; Ahern, M.M.; et al. Full cost accounting for the life cycle of coal. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1219, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, L.; Sala, S. Social impact assessment in the mining sector: Review and comparison of indicators frameworks. Resour. Policy 2018, 57, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markuszewska, I. From NIMBY to YIMBY: When a new open cast mine creates land use conflict. In Gospodarowanie Gruntami na Obszarach Wiejskich; Kołodziejczak, A., Kaczmarek, L., Eds.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2020; pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- The Future of Coal: Options for a Carbon-Constrained World; Technical Report. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwj4kIX84eXzAhUOy4sKHW4YDXsQFnoECA0QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fweb.mit.edu%2Fcoal%2FThe_Future_of_Coal.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2i86djRZS9x_uXVmKFQXRh (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Badera, K.; Kocoń, P. Local community opinions regarding the socio-environmental aspects of lignite surface mining: Experiences from central Poland. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, J.; Jurczyk, W. Social and environmental activities in the Polish mining region in the context of CSR. Resour. Policy 2020, 65, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepliński, B. Skutki Budowy Kopalni Odkrywkowej Węgla Brunatnego Na Złożu Oczkowice—Analiza Kosztów Dla Rolnictwa i Przetwórstwa Rolno-Spożywczego; Expertise: Poznań, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, W.; Pepliński, B.; Sadowski, A.; Czubak, W. Wpływ Planowanej Kopalni Oczkowice na Ekonomiczny, Produkcyjny i Społeczny Potencjał Rolnictwa i Jego Otoczenia na Agrobiznes Południowo-Zachodniej Części Województwa Wielkopolskiego; Expertise: Poznań, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The National Raw Material Policy; The Ministry of Environment: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjjst2l4-XzAhXOmIsKHa45C5gQFnoECAoQAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.pgi.gov.pl%2Fdokumenty-pig-pib-all%2Fkalendarium%2Fkal-2018%2F5399-polityka-surowcowa-panstwa%2Ffile.html&usg=AOvVaw0q9fqBraWv19P8vfAU9fvO (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Central Statistical Office. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-enegia (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Kuchler, M.; Bridge, G. Down the black hole: Sustaining national socio-technical imaginaries of coal in Poland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuila, O. Decarbonisation perspectives for the Polish economy. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivek, K.; Jiráasek, J.; Kavina, P.; Vojnarováa, M.; Kurkováa, T.; Baásováa, A. Divorce after hundreds of years of marriage: Prospects for coal mining in the Czech Republic with regard to the European Union. Energy Policy 2020, 142, 111524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuk, P.; Żuk, P.; Pluciński, P. Coal basin in Upper Silesia and energy transition in Poland in the context of pandemic: The socio-political diversity of preferences in energy and environmental policy. Resour. Policy 2021, 71, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryz, J.; Kaczmarczyk, B. Towards low-carbon European Union society: Young Poles’ perception of climate neutrality. Energies 2021, 14, 5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osička, J.; Kemmerzell, J.; Zoll, M.; Lehotský, L.; Černoch, F.; Knodt, M. What’s next for the European coal heartland? Exploring the future of coal as presented in German, Polish and Czech press. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 61, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markuszewska, I. Emotional landscape: Socio-environmental conflict and place attachment. In Experience from the Wielkopolska Region, 1st ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2019; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Urbańska, J. ‘Dla nas Biskupizna to jest pępkiem świata’. Rozumienie i przejawy lokalności na Biskupiźnie. In Biskupizna: Ziemia—Tradycja—Tożsamość; Brzezińska, A.W., Machowska, M., Eds.; Gminne Centrum Kultury i Rekreacji: Krobia, Poland, 2016; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejkowicz, K. Poczucie tożsamości i zmiany w krajobrazie kulturowym. In Biskupizna: Ziemia—Tradycja—Tożsamość; Brzezińska, A.W., Machowska, M., Eds.; Gminne Centrum Kultury i Rekreacji: Krobia, Poland, 2016; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sgroi, F.; Donia, E.; Alesi, D.R. Renewable energies, business models and local growth. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, D. Implementing wind power policy—Institutional frameworks and the beliefs of sovereigns. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petersen, J.P.; Heurkens, E. Implementing energy policies in urban development projects: The role of public planning authorities in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muthoora, T.; Fischer, T.B. Power and perception—from paradigms of specialist disciplines and opinions of expert groups to an acceptance for the planning of onshore windfarms in England—Making a case for Social Impact Assessment (SIA). Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Glanz, H. Identifying potential NIMBY and YIMBY effects in general land use planning and zoning. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 99, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Gray, T.; Haggett, C.; Swaffield, J. Re-visiting the ‘social gap’: Public opinion and relations of power in the local politics of wind energy. Environ. Polit. 2013, 22, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Howes, Y. Disruption to place attachment and the protection of restorative environments: A wind energy case study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R.; Lumsden, C.; O’Dowd, S.; Birnie, R.V. ‘Green on Green’: Public Perceptions of Wind Power in Scotland and Ireland. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2005, 48, 853–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulecki, K. Securitization and state encroachment on the energy sector: Politics of exception in Poland’s energy governance. Energy Policy 2020, 136, 111066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidaway, R. Resolving Environmental Disputes: From Conflict to Consensus; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Constitution of the Republic of Poland. J. Laws 1997. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjMhquC5OXzAhUitYsKHdZDDnkQFnoECBAQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fisap.sejm.gov.pl%2Fisap.nsf%2Fdownload.xsp%2FWDU19970780483%2FU%2FD19970483Lj.pdf&usg=AOvVaw016QbBTvvTbxcxNizDqfmF (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Brown, B.; Spiegel, S.J. Coal, climate justice, and the cultural politics of energy transition. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2019, 19, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil; Verso: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Emara, D.; Ezzat, M.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M.; Darwish, M.M.F. Novel Control Strategy for Enhancing Microgrid Operation Connected to Photovoltaic Generation and Energy Storage Systems. Electronics 2021, 10, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.; Shaheen, A.M.; Ginidi, A.R.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M.; Darwish, M.M.F. Estimating Parameters of Photovoltaic Models Using Accurate Turbulent Flow of Water Optimizer. Processes 2021, 9, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaza, A.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M.; Darwish, M.M.F. Optimal Estimation of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells Parameter Based on Coyote Optimization Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.S.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Abou El-Ela, A.; Ali, E.S.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M.; Darwish, M.M.F. Optimal Harmonic Mitigation in Distribution Systems with Inverter Based Distributed Generation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markuszewska, I. The Energy Landscape versus the Farming Landscape: The Immortal Era of Coal? Energies 2021, 14, 7008. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14217008

Markuszewska I. The Energy Landscape versus the Farming Landscape: The Immortal Era of Coal? Energies. 2021; 14(21):7008. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14217008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkuszewska, Iwona. 2021. "The Energy Landscape versus the Farming Landscape: The Immortal Era of Coal?" Energies 14, no. 21: 7008. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14217008

APA StyleMarkuszewska, I. (2021). The Energy Landscape versus the Farming Landscape: The Immortal Era of Coal? Energies, 14(21), 7008. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14217008