Decision-Making Processes of Renewable Energy Consumers Compared to Other Categories of Ecological Products

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- RQ1—

- What are the stages of the decision-making process of renewable energy consumer and whether it different from the decision-making process related to the purchase of other ecological products, including everyday products and durable goods?

- RQ2—

- How do the renewable energy consumers assess the level of adjusting the offer to their needs compared to the offer for other categories of ecological products and whether there are differences in the assessment of adjusting the offer with regard to renewable energy to the needs of customers in terms of their demographic characteristics?

- RQ3—

- How is the consumer of ecological products perceived by renewable energy buyers and by people who do not buy ecological products?

3. Materials and Research Methods

- −

- Renewable energy, the purchase of which is perceived in a broad way that considers the purchase of only this energy, as well as household appliances for its production (it is purchased by 31.8% of respondents);

- −

- Organic food (purchased by 48.0% of the respondents);

- −

- Biocosmetics and cleaning products (purchased by 45.8% of the respondents);

- −

- Electric cars (purchased by 25.2% of the respondents);

- −

- Ecological clothing (purchased by 42.9% of the respondents);

- −

- Green home furnishing products (purchased by 41.6% of the respondents).

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- In the last 3 months, did you buy an eco-certified product and/or do you have an electric car and/or do you use renewable energy sources in your household?

- □

- Yes—(people who have bought the organic product answer all questions)

- □

- No—(people who have not bought an ecological product do not answer questions 2–6)

- What drives you in your choice of the listed ecological products (Please choose a maximum of 3 answers for each of the products)

Specification Renewable Energy Organic Food Biocosmetics and Cleaning Products Electric Car Ecological Clothing Ecological

Home Furnishing Products- [1]

- I do not buy this category of ecological products

- [2]

- producer’s brand

- [3]

- product composition

- [4]

- product quality

- [5]

- product eco-certification

- [6]

- product origin (it comes from Poland)

- [7]

- ecological packaging

- [8]

- price

- [9]

- place of purchase

- [10]

- promotion

- [11]

- own experience

- [12]

- other people’s opinion

- [13]

- fashion

- [14]

- others, what …?

- Who usually makes a decision in your household to buy the following ecological products? (Please choose 1 answer for each of the products)

Specification Renewable Energy Organic Food Biocosmetics and Cleaning Products Electric Car Ecological Clothing Ecological Home

Furnishing Products- [1]

- I do (the respondent)

- [2]

- my partner

- [3]

- children

- [4]

- parents

- [5]

- it is a joint decision

- [6]

- everyone individually

- [7]

- others, please indicate who

- When purchasing ecological products, do you most often: (Please select 1 answer for each product category)

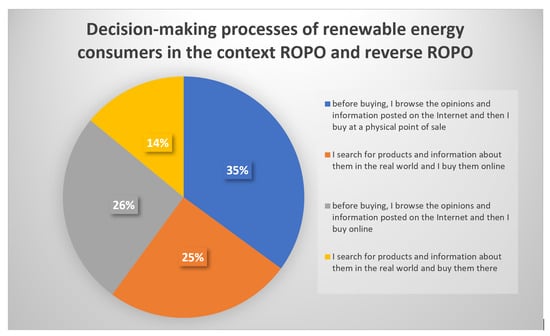

Ecological Product Description Renewable energy before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products at a physical point of sale

I search for products and information about them in the real world and I buy them online

before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products online

I search for products and information about them in the real world and buy them there

I have not bought such a product yetOrganic food before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy organic products at a physical point of sale

I search for products and information about them in the real world and I buy them online

before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy organic products online

I search for products and information about them in the real world and buy them there

I have not bought such a product yetBiocosmetics and cleaning products before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products at a physical point of sale

I search for products and information about them in the real world and I buy them online

before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products online

I search for products and information about them in the real world and buy them there

I have not bought such a product yetEcological clothing before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products at a physical point of sale

I search for products and information about them in the real world and I buy them online

before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products online

I search for products and information about them in the real world and buy them there

I have not bought such a product yetElectric cars before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products at a physical point of sale

I search for products and information about them in the real world and I buy them online

before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products online

I search for products and information about them in the real world and buy them there

I have not bought such a product yetEcological home furnishing products before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products at a physical point of sale

I search for products and information about them in the real world and I buy them online

before buying, I browse the opinions and information posted on the Internet and then I buy ecological products online

I search for products and information about them in the real world and buy them there

I have not bought such a product yet - Which of the descriptions best describes the way you do shopping? (please choose 1 answer for each product category)

Ecological Product Description Renewable energy when buying ecological products, I compare many offers and I think about the choice for a relatively long time

when buying ecological products, I compare several offers and I think about the choice for a relatively short time

I buy ecological products because of my habit

I buy ecological products on impulse

I have not bought such a product yetOrganic food when buying organic products, I compare many offers and I think about the choice for a relatively long time

when buying organic products, I compare several offers and I think about the choice for a relatively short time

I buy organic products because of my habit

I buy organic products on impulse

I have not bought such a product yetBiocosmetics and cleaning products when buying ecological products, I compare many offers and I think about the choice for a relatively long time

when buying ecological products, I compare several offers and I think about the choice for a relatively short time

I buy ecological products because of my habit

I buy ecological products on impulse

I have not bought such a product yetEcological clothing when buying ecological products, I compare many offers and I think about the choice for a relatively long time

when buying ecological products, I compare several offers and I think about the choice for a relatively short time

I buy ecological products because of my habit

I buy ecological products on impulse

I have not bought such a product yetElectric cars when buying ecological products, I compare many offers and I think about the choice for a relatively long time

when buying ecological products, I compare several offers and I think about the choice for a relatively short time

I buy ecological products because of my habit

I buy ecological products on impulse

I have not bought such a product yetEcological home furnishing products when buying ecological products, I compare many offers and I think about the choice for a relatively long time

when buying ecological products, I compare several offers and I think about the choice for a relatively short time

I buy ecological products because of my habit

I buy ecological products on impulse

I have not bought such a product yet - Please assess the level of adjustment of the offer of ecological products to your needs (Please choose 1 answer for each product category)

Ecological Product Level of Adjustment Renewable energy is fully adjusted to my needs

is fairly adjusted

it is hard to say

is rather not adjusted

is not at all adjustedOrganic food is fully adjusted to my needs

is fairly adjusted

it is hard to say

is rather not adjusted

is not at all adjustedBiocosmetics and cleaning products are fully adjusted to my needs

are fairly adjusted

it are hard to say

are rather not adjusted

are not at all adjustedEcological clothing is fully adjusted to my needs

is fairly adjusted

it is hard to say

is rather not adjusted

is not at all adjustedElectric cars are fully adjusted to my needs

are fairly adjusted

it are hard to say

are rather not adjusted

are not at all adjustedEcological home furnishing products are fully adjusted to my needs

are fairly adjusted

it are hard to say

are rather not adjusted

are not at all adjusted - The following are pairs of contradictory human traits. Please describe the consumer of ecological products by putting an X next to each pair of features.Consumer of ecological products:

acts reasonably [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] acts emotionally is demanding [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is not demanding values quality [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] values a low price is loyal towards brands [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] changes product brands prefers local products [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] prefers global products is wealthy [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is not wealthy is well educated [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is poorly educated is older [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is younger is modern [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is traditional is active [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is passive lives in inner harmony [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is torn internally is modest [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] exalts himself/herself is extrovert [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is introvert is himself/herself [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is a “poser” is sensitive [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is insensitive follows the opinions of others [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] makes decisions by himself/herself cares for the environment [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] does not care for the environment likes new technologies [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] dislikes new technologies avoids risk [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] is inclined to risk - I perceive myself as a person who is (please select 1 answer)

- [1]

- entrepreneurial

- [2]

- modern

- [3]

- traditional

- [4]

- ambitious

- [5]

- sensitive

- [6]

- tolerant

- [7]

- optimistic

- [8]

- full of passion

- Here is the list of values. Please select the 3 most important and the 3 least important values for you.

- [1]

- health

- [2]

- inner harmony

- [3]

- contact with nature

- [4]

- security

- [5]

- knowledge

- [6]

- education

- [7]

- high material status

- [8]

- pleasure

- [9]

- life full of sensations

- [10]

- self-respect

- [11]

- personality development

- [12]

- self-fulfillment

- [13]

- freedom

- [14]

- love

- [15]

- friendship

- [16]

- family life

- [17]

- work for the environment

- ME1.

- Select your gender (please choose one answer)

- [1]

- Woman

- [2]

- Man

- ME2.

- Please provide your age

- [1]

- 18–24

- [2]

- 25–34

- [3]

- 35–44

- [4]

- 45–54

- [5]

- 55–65

- ME3.

- What is your education so far? (please select one answer)

- [1]

- Primary/vocational

- [2]

- Secondary

- [3]

- University

- ME4.

- Which voivodeship do you live in? (please select one answer)

- [1]

- Lower Silesian

- [2]

- Kuyavian-Pomeranian

- [3]

- Lublin

- [4]

- Lubusz

- [5]

- Łódź

- [6]

- Lesser Poland

- [7]

- Masovian

- [8]

- Opole

- [9]

- Subcarpathia

- [10]

- Podlaskie

- [11]

- Pomeranian

- [12]

- Silesian

- [13]

- Holy Cross

- [14]

- Warmian-Masurian

- [15]

- Greater Poland

- [16]

- West Pomeranian

- ME5.

- What is the size of the town/city in which you live (please mark one answer)?

- [1]

- Village

- [2]

- Town with up to 20 thousand inhabitants

- [3]

- City with 20–50 thousand inhabitants

- [4]

- City with 50–100 thousand inhabitants

- [5]

- City with 100–200 thousand inhabitants

- [6]

- City with 200–500 thousand inhabitants

- [7]

- City with over 500 thousand inhabitants

- ME6.

- How many people are there in your household, including yourself?

References

- Qin, Y.; Wang, W. Research on Ecological Compensation Mechanism for Energy Economy Sustainable Based on Evolutionary Game Model. Energies 2022, 15, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, S. Strategic environmental assessment for energy production. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3489–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Mortberg, U.; Brown, N. Energy models from a strategic environmental assessment perspective in an EU context—What is missing concerning renewables? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žičkienė, A.; Morkunas, M.; Volkov, A.; Balezentis, T.; Streimikiene, D.; Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I. Sustainable Energy Development and Climate Change Mitigation at the Local Level through the Lens of Renewable Energy: Evidence from Lithuanian Case Study. Energies 2022, 15, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrałek, J. Zrównoważona konsumpcja jako element zrównoważonego rozwoju gospodarczego. In Zrównoważona Konsumpcja w Polskich Gospodarstwach Domowych—Postawy, Zachowania, Determinanty; Smyczek, S., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2020; pp. 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.; Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. (Eds.) The Ethical Consumer; SAGE: London, UK, 2005; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Patrzełek, W. Konwestycja Jako Forma Dekonsumpcji; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2022; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Baruk, A.I. Prosumers’ Needs Satisfied Due to Cooperation with Offerors in the Context of Attitudes toward Such Cooperation. Energies 2021, 14, 7821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Rahman, Z. Roles and resource contributions of customers in value co-creation. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Sivakumar, K.; Evans, K.R.; Zou, S. Effect of customer participation on service outcomes: The moderating role of participation readiness. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, G.; Sovacool, B.; Aall, C.; Nilsson, M.; Barbier, C.; Herrmann, A.; Bruyère, S.; Andersson, C.; Skold, B.; Nadaud, F.; et al. It starts at home? Climate policies targeting household consumption and behavioral decisions are key to low-carbon futures. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 52, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M. Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being; Global Edition; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, L.; Wisenblit, J. Consumer Behavior; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Lehr, B. Behavioral Economics: Evidence, Theory, and Welfare; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski, G. Ryzyko w Decyzjach Nabywczych Konsumentów; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2010; pp. 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Assael, H. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action; South-Western College Publishing: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2000; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tinnila, M.; Oorni, A.; Raijas, A. Developing Consumer Preference-Profiles as a Basis for Multi-Channel Service Concepts. In Managing Business in a Multi-Channel World: Success Factors for E-Business; Saarinen, T., Tinnilä, M., Tseng, A., Eds.; Idea Group Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2005; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Lipowski, M. Kanał komunikacji a kanał dystrybucji—Zanikanie różnic i ich konsekwencje, Studia Ekonomiczne. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. W Katowicach 2016, 254, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Aw, E.C.-X.; Basha, N.K.; Ng, S.I.; Ho, J.A. Searching online and buying offline: Understanding the role of channel-, consumer-, and product-related factors in determining webrooming intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.T.; Fu, F.Q.; Speck, P.S. Information Search and Purchase Patterns in a Multichannel Service Industry. Serv. Mark. Q. 2012, 33, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.C.; Jian, I.Y.; Chi, H.L.; Yang, D.; Chan, E.H.W. Are you an energy saver at home? The personality insights of household energy conservation behaviors based on theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamir, L.; Kiesewetter, G.; Wagner, F.; Schöpp, W.; Filatova, T.; Voinov, A.; Bressers, H. Assessing the macroeconomic impacts of individual behavioral changes on carbon emissions. Clim. Chang. 2020, 158, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamir, L.; Ivanova, O.; Filatova, T.; Voinov, A.; Bressers, H. Demand-side solutions for climate mitigation: Bottom-up drivers of household energy behavior change in the Netherlands and Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 62, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, N.; Brandt, N. Determinants of households’ investment in energy efficiency and renewables: Evidence from the OECD survey on household environmental behaviour and attitudes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, B.; Schleich, J. Residential energy-efficient technology adoption, energy conservation, knowledge, and attitudes: An analysis of European countries. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureti, T.; Benedetti, I. Analysing Energy-Saving Behaviours in Italian Households. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2021, 39, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewable Energy Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Renewable_energy_statistics (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Grębosz-Krawczyk, M.; Zakrzewska-Bielawska, A.; Glinka, B.; Glińska-Neweś, A. Why Do Consumers Choose Photovoltaic Panels? Identification of the Factors Influencing Consumers’ Choice Behavior regarding Photovoltaic Panel Installations. Energies 2021, 14, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Suter, T.A.; Churchill, G.A. Basic Marketing Research, Customer Insights and Managerial Action; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- ePanel.pl—The Longest Experience, the Highest Quality. Available online: https://arc.com.pl/en/epanel-pl-2/ (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Forrest, E. Internet Marketing Intelligence. Research Tools, Techniques, and Resources; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wódkowski, A. (Ed.) Badania Marketingowe. Rocznik Polskiego Towarzystwa Badaczy Rynku i Opinii, Edycja XXV; PTBRiO: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Gumiński, M.; Guzowski, W.; Huet, M.; Kwiatkowska, M.; Mordan, P.; Orczykowska, M.; Wegner, M. Społeczeństwo informacyjne w Polsce w 2021 r. In Information Society in Poland in 2021; Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Urząd Statystyczny w Szczecinie: Warszawa, Szczecin, 2021; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple Comparisons among Means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1961, 56, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwin, D.F. Factor analysis. In Encyclopedia of Sociology; Borgatta, E.F., Montgomery, R.J.V., Eds.; Macmillan Reference: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Child, D. The Essentials of Factor Analysis; Continuum: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.O.; Mueller, C.W. Factor Analysis. Statistical Methods and Practical Issues; Sage Publishing: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska, S.; Cypryańska, M. (Eds.) Statystyczny Drogowskaz. Praktyczne Wprowadzenie do Wnioskowania Statystycznego; Wydawnictwo Akademickie SEDNO: Warszawa, Poland, 2013; pp. 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- Aczel, A.D.; Sounderpandian, J. Statystyka w Zarządzaniu; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; pp. 913–920. [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziński, J. Trafność i Rzetelność Testów Psychologicznych; Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne: Gdańsk, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rószkiewicz, M. Metody Ilościowe w Badaniach Marketingowych; Wydawnictwa Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom, M.; Klintman, M. Eco-Standards, Product Labeling and Green Consumerism; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Haski-Leventhal, D. Altruism and volunteerism: The perceptions of altruism in four disciplines and their impact on the study of volunteerism. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2009, 39, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagrani, K. Case study: ROPO—Its effect on e-commerce-good or bad? Int. Res. J. Mod. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2020, 02, 582–584. [Google Scholar]

- Sass-Staniszewska, P.; Binert, K. Raport “E-Commerce w Polsce. Gemius dla e-Commerce Polska”; Gemius S.A.: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://www.gemius.pl/wszystkie-artykuly-aktualnosci/e-commerce-w-polsce-2020.html (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Hoyer, W.D.; MacInnis, D.J.; Pieters, R. Consumer Behavior; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Melovic, B.; Mitrovic, S.; Rondovic, B.; Alpackaya, I. Green (Ecological) Marketing in Terms of Sustainable Development and Building a Healthy Environment. In International Scientific Conference Energy Management of Municipal Transportation Facilities and Transport EMMFT 2017; Murgul, V., Popovic, Z., Eds.; EMMFT 2017; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 692; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerényi, A.; McIntosh, R.W. Steps Towards Realising Global Sustainable Development. In Sustainable Development in Changing Complex Earth Systems; Kerényi, A., McIntosh, R.W., Eds.; Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| People Who Bought an Ecological Product in the Last 3 Months | People Who Did Not Buy an Ecological Product in the Last 3 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent |

| 509 | 49.3% | 523 | 50.7% | |

| Gender | ||||

| Man | 265 | 47.8% | 293 | 52.2 |

| Woman | 244 | 52.2% | 230 | 47.8 |

| Total | 509 | 100.0% | 523 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 80 | 12.9 | 55 | 9.0 |

| 25–34 | 133 | 24.8 | 96 | 17.5 |

| 35–44 | 130 | 29.3 | 99 | 21.7 |

| 45–54 | 78 | 14.5 | 144 | 25.6 |

| 55–65 | 88 | 18.5 | 129 | 26.2 |

| Total | 509 | 100.0% | 523 | 100.0 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary/vocational | 57 | 11.1 | 81 | 16.3 |

| Secondary | 230 | 44.4 | 240 | 45.4 |

| University | 222 | 44.5 | 202 | 38.3 |

| Total | 509 | 100.0% | 523 | 100.0 |

| Voivodeship | ||||

| Lower Silesian | 49 | 9.4 | 39 | 7.4 |

| Kuyavian-Pomeranian | 17 | 3.3 | 25 | 5.0 |

| Lublin | 27 | 5.4 | 31 | 6.1 |

| Lubusz | 15 | 2.7 | 12 | 2.2 |

| Łódź | 29 | 5.7 | 28 | 5.2 |

| Lesser Poland | 53 | 10.4 | 60 | 11.4 |

| Masovian | 104 | 20.4 | 78 | 14.7 |

| Opole | 7 | 1.5 | 11 | 2.3 |

| Subcarpathia | 30 | 5.9 | 20 | 4.3 |

| Podlaskie | 12 | 2.5 | 17 | 3.0 |

| Pomeranian | 18 | 3.5 | 29 | 5.7 |

| Silesian | 68 | 13.2 | 88 | 16.6 |

| Holy Cross | 17 | 3.5 | 14 | 2.7 |

| Warmian-Masurian | 11 | 2.1 | 11 | 2.1 |

| Greater Poland | 35 | 7.0 | 42 | 7.9 |

| West Pomeranian | 17 | 3.5 | 18 | 3.4 |

| Total | 509 | 100.0% | 523 | 100.0 |

| Size of town | ||||

| Village | 153 | 35.1 | 186 | 40.9 |

| Town with up to 20 thousand inhabitants | 79 | 14.4 | 67 | 11.7 |

| City with 20–50 thousand inhabitants | 55 | 11.0 | 58 | 11.0 |

| City with 50–100 thousand inhabitants | 45 | 8.1 | 45 | 7.9 |

| City with 100–200 thousand inhabitants | 58 | 10.6 | 42 | 7.4 |

| City with 200–500 thousand inhabitants | 45 | 7.9 | 58 | 10.0 |

| City with over 500 thousand inhabitants | 74 | 12.9 | 67 | 11.1 |

| Total | 509 | 100.0% | 523 | 100.0 |

| Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (rho) | Renewable Energy | Organic Food | Biocosmetics and Cleaning Products | Ecological Clothing | Electric Car | Ecological Home Furnishing Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy | 1.000 | 0.409 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.544 ** |

| Organic food | 0.409 ** | 1.000 | 0.627 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.440 ** |

| Biocosmetics and cleaning products | 0.409 ** | 0.627 ** | 1.000 | 0.546 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.523 ** |

| Ecological clothing | 0.465 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.546 ** | 1.000 | 0.422 ** | 0.624 ** |

| Electric car | 0.603 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.422 ** | 1.000 | 0.460 ** |

| Ecological home furnishing products | 0.544 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.624 ** | 0.460 ** | 1.000 |

| Category-Assessment of the Level of Offer Adjustment to the Needs of Consumers in the Scope of: | Component | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| organic food | 0.830 | 0.202 |

| biocosmetics and cleaning products | 0.873 | 0.189 |

| ecological clothing | 0.715 | 0.416 |

| electric cars | 0.171 | 0.877 |

| renewable energy | 0.305 | 0.830 |

| ecological home furnishing products | 0.592 | 0.579 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sobocińska, M.; Mazurek-Łopacińska, K.; Graczyk, A.; Kociszewski, K.; Krupowicz, J. Decision-Making Processes of Renewable Energy Consumers Compared to Other Categories of Ecological Products. Energies 2022, 15, 6272. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15176272

Sobocińska M, Mazurek-Łopacińska K, Graczyk A, Kociszewski K, Krupowicz J. Decision-Making Processes of Renewable Energy Consumers Compared to Other Categories of Ecological Products. Energies. 2022; 15(17):6272. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15176272

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobocińska, Magdalena, Krystyna Mazurek-Łopacińska, Andrzej Graczyk, Karol Kociszewski, and Joanna Krupowicz. 2022. "Decision-Making Processes of Renewable Energy Consumers Compared to Other Categories of Ecological Products" Energies 15, no. 17: 6272. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15176272

APA StyleSobocińska, M., Mazurek-Łopacińska, K., Graczyk, A., Kociszewski, K., & Krupowicz, J. (2022). Decision-Making Processes of Renewable Energy Consumers Compared to Other Categories of Ecological Products. Energies, 15(17), 6272. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15176272