Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Behaviors of Generation Z in Poland Stimulated by Mobile Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Sustainable Behaviors and Consumption

2.1.2. Mobile Applications

2.2. Hypothesis Development

- the implementation of the Glasgow Climate Pact-the outcome of COP26;

- the analysis of innovative (using mobile applications) methods of communication and education in the field of responsible behavior explored, inter alia, by Hase et al. [39], Reichel et al. [35], Lutzke et al. [41], Ngubelanga [17], Yadav et al. [18], Dong [20], Sidiropoulos et al. [21], Stepaniuk [22], Yan et al. [43], Calafell et al. [42] Jiménez-Parra et al. [30], Hawkins and Horst [15].

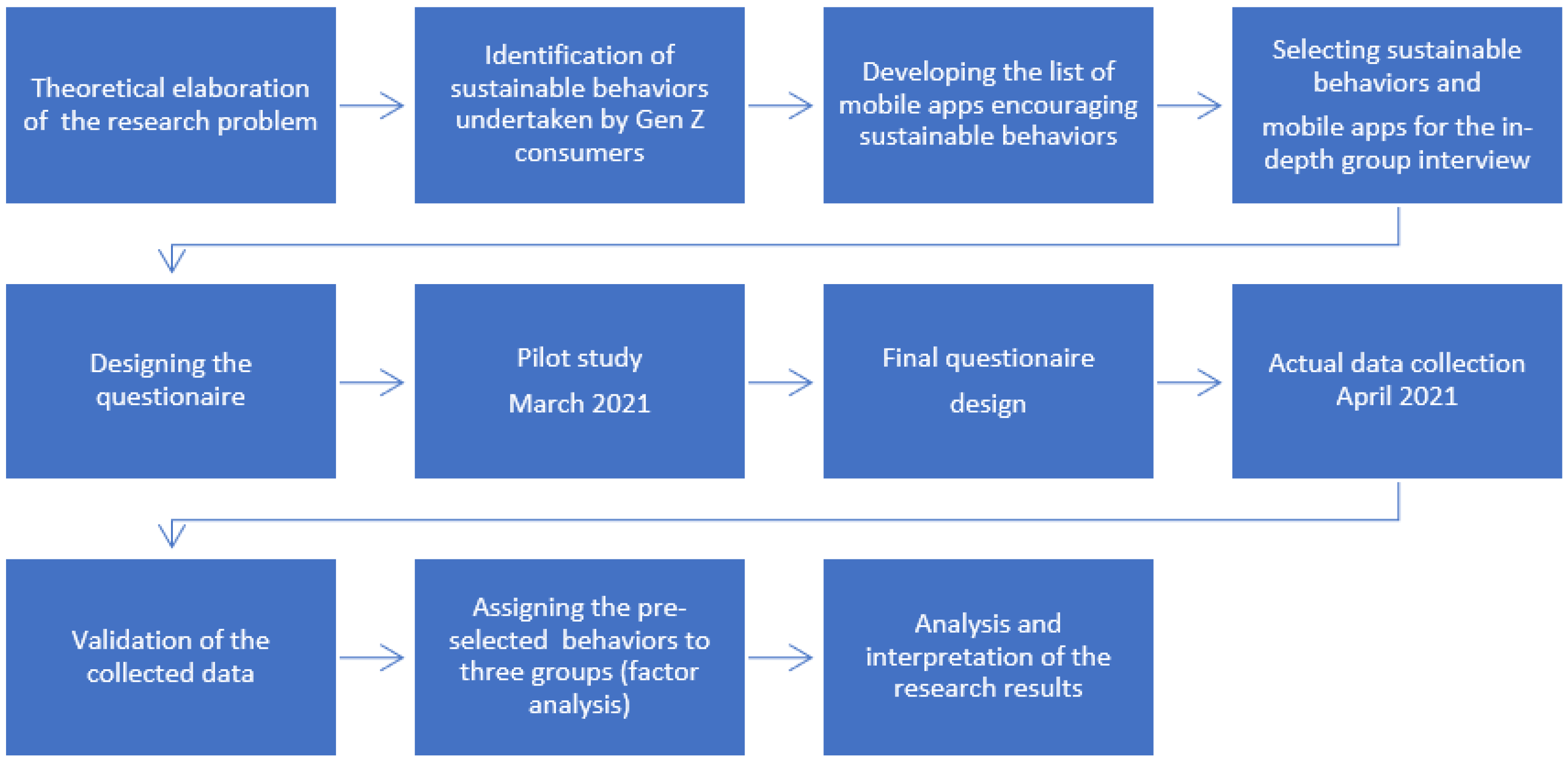

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Socially and Environmentally Sustainable Behavior

4.2. Differences in the Results of the Behavior Areas due to the Independent Variables

4.3. Differences in the Results of Behavior Areas and the Recognition of Individual Applications

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- To date, research shows that among all the factors influencing pro-environmental behavior, four types are most often mentioned: perception of environmental risk, knowledge about the environment, concern for the natural environment and willingness to participate in pro-environmental actions. In the case of the first two factors, it is important to reach individuals with information, and in the case of the Generation Z, the information transfer channels are social media and mobile applications;

- Actions should be taken to increase the recognition of pro-environmental mobile applications by Generation Z in order to promote environmentally and socially sustainable attitudes;

- The development of social media in the last 20 years has inspired radical transformations in the information environment and consequently it is important to conduct research exploring how thematic applications impact pro-environmental and socially sustainable behavior;

- Mobile applications are not only a source of information, but also tools supporting the planning and implementation of behaviors that will have the least destructive impact on the natural and social environment;

- Legal and economic factors play a significant role in encouraging socially and environmentally responsible behavior.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

- Methodical: it is necessary to use various research methods in order to recognize sustainable behaviors and the role played by mobile applications in encouraging these behaviors. Further studies could use methods such as: an experiment, a focus group and, in the case of mobile applications, a customer satisfaction index.

- Scientific: the conducted research prompted the authors to propose a model of socially and environmentally sustainable behavior stimulated by mobile applications (Figure 3).

6.2. Practical Implications

- In order to stimulate environmentally and socially sustainable behaviors, it is necessary to disseminate information about mobile applications that can both initiate such behaviors and consolidate them. To perform their function, they must be effectively promoted and widely used. The collected data provide guidelines for actors along the entire chain of production and distribution of consumer products enabling identification of consumer expectations and behavior;

- The state institutions and the European Union bodies should continue to put effort into creating legal and financial instruments encouraging citizens to behave in a socially and environmentally responsible manner.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Consilium Europa. 2021. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/pl/meetings/international-summit/2021/06/11-13/# (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Strategy (2019–2024). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Poland Emissions. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/poland/news/200917_emissions_cut_pl (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Germanwatch. 2021. Available online: https://germanwatch.org/en/19552 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- CCPI. 2021. Available online: https://ccpi.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Zheng, G.-W.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Akter, A. Perceived Environmental Responsibilities and Green Buying Behavior: The Mediating Effect of Attitude. Sustainability 2021, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełczewski, D. Struktura pojęcia konsumpcji zrównoważonej. (Structure of the idea of sustainable consumption). Ekonomia i Środowisko 2007, 2, 36–50. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-cf942023-e052-450a-ac73-3a24796856f8 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry PRissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Šajn, N. Environmental impact of the textile and clothing industry. What consumers need to know. Eur. Parliam. Res. Serv. 2019. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/633143/EPRS_BRI(2019)633143_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- The 2019 Ethical Fashion: Report the Truth behind the Barcode. Available online: https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/files/documents/FashionReport_2019_9-April-19-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Thornton, I. That Is a Huge Wardrobe and Clothing Mistake!: The Unethical Consumption Habits of YouTube’s Fashion Influencers and the Environmental Consequences of a Disposable Lifestyle. Pell Sch. Sr. Theses 2021, 136. Available online: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/136 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ting, T.Z.-T.; Stagner, J.A. Fast fashion–wearing out the planet. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 79, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Abbott, P.; Haque, S. Tackling modern slavery: A sustainability accounting perspective. Futurum 2021. Available online: https://aura.abdn.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/2164/17789/Islam_etal_Tackling_modern_slavery_VOR.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Sohna, J.; Nielsenb, K.S.; Birkvedc, M.; Joanesd, T.; Gwozdzd, W. The environmental impacts of clothing: Evidence from United States and three European countries. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 2153–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.; Horst, N. Ethical consumption? There’s an app for that. Digital technologies and everyday consumption practices. Can. Geogr. 2020, 64, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital. 2020. Available online: https://mobirank.pl/2020/01/31/raport-digital-i-mobile-na-swiecie-w-2020-roku/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ngubelanga, A. Modeling mobile commerce applications’ antecedents of customer satisfaction among millennials: An extended TAM perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Tarhini, A. A multi-analytical approach to understand and predict the mobile commerce adoption. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2016, 29, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardjono, W.; Selviyanti, E.; Mukhlis, M.; Tohir, M. Global issues: Utilization of e-commerce and increased use of mobile commerce application as a result of the covid-19 pandemic. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1832, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z. Construction of mobile E-commerce platform and analysis of its impact on E-commerce logistics customer satisfaction. Complexity 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulos, V.; Bechtsis, D.; lachos, D. An augmented reality symbiosis software tool for sustainable logistics activities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepaniuk, K. Social media and tourism. The analysis of selected current and future research trends. Eur. J. Serv. Manag. 2015, 16, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guy, T.; Sgan-Cohen, H.; Spanier, A.B.; Mann, J. Perceptions and attitudes toward the use of a mobile health app for remote monitoring of gingivitis and willingness to pay for mobile health apps (part 3): Mixed methods study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Guo, X.; Peng, Z.; Lai, K.; Vogel, D. Investigating the effects of negative health mood on acceptance of mobile health services. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 22, 228–247. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/investigating-effects-negative-health-mood-on/docview/2562579390/se-2?accountid=48272 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Orovwode, H.; Wara, S.; Mercy, T.J.; Abudu, M.; Adoghe, A.; Ayara, W. Development and Implementation of a Web Based Sustainable Alternative Energy Supply for a Retrofitted Office; The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.proquest.com/conference-papers-proceedings/development-implementation-web-based-sustainable/docview/2130607660/se-2?accountid=48272 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Sheng, J.S.; Tan, K.H.; Awang, M.M. Generic digital equity model in education: Mobile-assisted personalized learning (MAPL) through e-modules. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryilmaz, S. Compare teachers and students attitudes according to mobile educational applications. TOJET Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 20. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/compare-teachers-students-attitudes-according/docview/2478760481/se-2?accountid=48272 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Dakir, M.; Mushfi El, I.B.; Zulfajri Muali, C.; Baharun, H.; Ferdianto, D.; Al-Farisi, M. Design seamless learning environment in higher education with mobile device. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1899, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, M.N.; Wannous, M. The Use of Cloud Computing and Mobile Technologies to Facilitate Access to an E-Learning Solution in Higher Education Context Work in Progress; The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.proquest.com/conference-papers-proceedings/use-cloud-computing-mobile-technologies/docview/1922953704/se-2?accountid=48272 (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Jiménez-Parra, B.; González-Álvarez, N.; Godos-Díez, J.-L.; Cabeza-García, L. Taking advantage of students’ passion for apps in sustainability and CSR teaching. Sustainability 2019, 11, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Oliveira Malaquias, F.F.; da Silva Júnior, R.J. The use of m-government applications: Empirical evidence from the smartest cities of brazil. Inf. Technol. People 2021, 34, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balińska, A.; Jaska, E.; Werenowska, A. The role of eco-apps in encouraging pro-environmental behavior of young people studying in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, G.D. Health co-benefits. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 863–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Moeltner, K.; Schmidthaler, M.; Reichl, J. An empirical analysis of local opposition to new transmission lines across the EU-27. Energy J. 2016, 37, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, J.; Cohen, J.J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Kollmann, A.; Azarova, V. The drivers of individual climate actions in Europe. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, B. Air Pollution in Cities: Urban and Transport Planning Determinants and Health in Cities. In Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning; Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Khreis, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariolet, J.-M.; Colombert, M.; Vuillet, M.; Diab, Y. Assessing the resilience of urban areas to traffic-related air pollution: Application in Greater Paris. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutter, W.; Neidell, M. Voluntary information programs and environmental regulation: Evidence from ‘Spare the Air’. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2009, 58, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, V.; Mahl, D.; Schäfer, M.S.; Keller, T.R. Climate change in news media across the globe: An automated analysis of issue attention and themes in climate change coverage in 10 countries (2006–2018). Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, J.; Cattaneo, C.; d’Adda, G.; Tavoni, M. Can social information programs be more effective? The role of environmental identity for energy conservation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutzke, L.; Drummond, C.; Slovic, P.; Árvai, J. Priming critical thinking: Simple interventions limit the influence of fake news about climate change on Facebook. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 58, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafell, G.; Banqué, N.; Viciana, S. Purchase and use of new technologies among young people: Guidelines for sustainable consumption education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, C.; Siddik, A.B.; Akter, N.; Dong, Q. Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of FinTech. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joris, M. Willingness of Online Respondents to Participate in Alternative Modes of Data Collection. Surv. Pract. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capiene, A.; Rutelione, A.; Tvaronaviciene, M. Pro-environmental and pro-social engagement in sustainable consumption: Exploratory study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, E. The contribution of ICT adoption to sustainability: Households’ perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Schultz, P.W. Culture and the natural environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concari, A.; Kok, G.; Martens, P. A systematic literature review of concepts and factors related to pro-environmental consumer behaviour in relation to waste management through an interdisciplinary approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelcic, J.R.; Naughton, C.C.; Verbyla, M.E.; Zhang, Q.; Schweitzer, R.W.; Oakley, S.M.; Wells, E.C.; Whiteford, L.M. The Grandest Challenge of All: The Role of Environmental Engineering to Achieve Sustainability in the World’s Developing Regions. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2017, 34, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Wong, W.P.; Soh, K.L. An overview of the substance of Resource, Conservation and Recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.K.; Patro, A.; Harindranath, R.M.; Kumar, N.S.; Panda, D.K.; Dubey, R. Perceived government initiatives: Scale development, validation and impact on consumers’ pro-environmental behaviour. Energy Policy 2021, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musova, Z.; Musa, H.; Matiova, V. Environmentally responsible behaviour of consumers: Evidence from Slovakia. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipiak, O. W kierunku świadomej konsumpcji–nowe konteksty. Rynek-Społeczeństwo-Kultura 2018, 4, 114–117. Available online: https://kwartalnikrsk.pl/Artykuły/RSK-4-2018/RSK-4-2018-Filipiak-W-kierunku-swiadomej-konsumpcji.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Xiao, C.; Hong, D. Gender differences in environmental behaviors in China. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerichevskyi, S.; Kniazieva, T.; Kolbushkin, Y.; Reshetnikova, I.; Olejniczuk-Merta, A. Environmental orientation of consumer behaviour: Motivational component. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Feelings that Make a Difference: How Guilt and Pride Convince Consumers of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Consumption Choices. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is Eco-Friendly Unmanly? The Green-Feminine Stereotype and Its Effect on Sustainable Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swim, J.K.; Vescio, T.K.; Dahl, J.L.; Zawadzki, S.J. Gendered discourse about climate change policies. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 48, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, M.; Gazley, B.; Reynolds, H.; Browning, E.G.; Sandweiss, E.; Shanahan, J. Public support for local adaptation policy: The role of social-psychological factors, perceived climatic stimuli, and social structural characteristics. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahsay, G.A.; Nordén, A.; Bulte, E. Women participation in formal decision-making: Empirical evidence from participatory forest management in Ethiopia. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 70, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Fornara, F.; Carrus, G. Predicting pro-environmental behaviours in the urban context: The direct or moderated effect of urban stress, city identity, and worldviews. Cities 2019, 88, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, P.S.; Martins, R.D.; Macke, J.; Sarate, J.A.R. Green, but not as green as that: An analysis of a Brazilian bike-sharing system. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenack, I.; Roggero, M. Many roads to Paris: Explaining urban climate action in 885 European cities. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 72, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzonko, A.; Balińska, A.; Sieczko, A. Pro-environmental behaviors of generation Z in the context of the concept of homo socio-oeconomicus. Energies 2021, 14, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Xu, J. A comparative study of the role of interpersonal communication, traditional media and social media in pro-environmental behavior: A china-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 17, 1883. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rufat, S.; Botzen, W.J.W. Drivers and dimensions of flood risk perceptions: Revealing an implicit selection bias and lessons for communication policies. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 73, 102465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, C.; Lane, M.; Morse-Jones, S.; Brooks, K.; Viner, D. The ‘co’ in co-production of climate action: Challenging boundaries within and between science, policy and practice. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigermann, U. Knowledge integration in sustainability governance through science-based actor networks. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 6, 102314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Areas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Specification of Behaviors | Purchasing Enhanced by Visual Identification (I) | Sustainable Consumption (II) | Behaviors Stimulated by Legal Regulations and Economic Factors (III) |

| Buying food with the FAIR TRADE label | 0.756 | 0.105 | 0.028 |

| Buying eco-certified clothes | 0.754 | 0.247 | −0.026 |

| Buying organic food | 0.740 | 0.075 | 0.100 |

| Buying “zero waste” products | 0.699 | 0.205 | 0.208 |

| Buying products in recycled packaging | 0.649 | 0.189 | 0.236 |

| Using eco-friendly laundry and cleaning products | 0.587 | 0.111 | 0.345 |

| Resignation from using public transport in favor of walking for short distances | 0.026 | 0.666 | 0.242 |

| Resignation from using a car in favor of public transport | 0.031 | 0.624 | 0.003 |

| Getting around by bike | 0.169 | 0.564 | 0.220 |

| Use of shared car transport (e.g., Blablacar) | 0.338 | 0.562 | −0.032 |

| Buying second-hand clothes | 0.241 | 0.555 | 0.000 |

| Sorting waste | 0.021 | −0.004 | 0.727 |

| Saving water | 0.177 | 0.168 | 0.715 |

| Packing fruit and vegetables in reusable bags instead of single-use bags | 0.388 | 0.174 | 0.519 |

| VARIANCE (cumulative percentage) | 23.761 | 38.059 | 49.821 |

| Variables | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 62.2 |

| Men | 37.8 | |

| Place of residence | Village | 25.4 |

| City ≤ 50,000 residents | 15.5 | |

| Cities of 50,000 to 500,000 residents | 15.0 | |

| Cities ≥ 500,000 residents | 41.1 | |

| Household income per capita | ≤PLN 1000 (EUR221) | 9.1 |

| PLN 1000–2000 (EUR 222–441) | 25.6 | |

| PLN 2000–3000 (EUR 442–662) | 33.7 | |

| ≥PLN 3000 (EUR 663) | 31.6 | |

| Variable | n | M | Me | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buying products in recycled packaging | 758 | 3.03 | 3.0 | 1.00 |

| Buying organic food | 733 | 2.78 | 3.0 | 1.06 |

| Buying “zero waste” products | 700 | 2.56 | 3.0 | 1.09 |

| Using eco-friendly laundry and cleaning products | 681 | 2.41 | 2.0 | 1.08 |

| Buying clothes with eco-labels (environmental certification) | 678 | 2.38 | 2.0 | 1.12 |

| Buying food with FAIR TRADE label | 642 | 2.32 | 2.0 | 1.10 |

| Resignation from using public transport in favor of walking for short distances | 722 | 3.38 | 4.0 | 1.26 |

| Buying second-hand clothes | 668 | 2.89 | 3.0 | 1.42 |

| Getting around by bike | 722 | 3.14 | 3.0 | 1.34 |

| Car sharing (e.g., Blablacar) | 563 | 2.47 | 2.0 | 1.34 |

| Resignation from using a car in favor of public transport | 715 | 3.14 | 3.0 | 1.39 |

| Packing fruit and vegetables in reusable bags instead of single-use bags | 749 | 3.12 | 3.0 | 1.42 |

| Saving water | 766 | 3.55 | 4.0 | 1.00 |

| Sorting waste | 761 | 3.72 | 4.0 | 1.04 |

| Behavior Areas | M | Me | Q1 | Q3 | SD | Friedman ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchasing activity enhanced by visual identification (Area I) | 2.44 | 2.42 | 1.83 | 3.0 | 0.816 | Chi2 = 526.234 p < 0001 I < II, I < III, II < III * |

| Sustainable consumption (Area II) | 2.78 | 2.80 | 2.20 | 3.4 | 0.873 | |

| Behaviors stimulated by legal regulations and economic factors (Area III) | 3.42 | 3.33 | 3.00 | 4.0 | 0.854 |

| Behavior Areas | Gender | M | Me | Q1 | Q3 | SD | Z, p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchasing activity enhanced by visual identification (Area I) | Women | 2.49 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 0.79 | Z = 2.738 p = 0.006 |

| Men | 2.36 | 2.33 | 1.67 | 2.83 | 0.85 | ||

| Sustainable consumption (Area II) | Women | 2.86 | 2.80 | 2.20 | 3.60 | 0.87 | Z = 3.488 p < 0.001 |

| Men | 2.65 | 2.60 | 2.00 | 3.20 | 0.86 | ||

| Behaviors stimulated by legal regulations and economic factors (Area III) | Women | 3.47 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 0.86 | Z = 2.182 p = 0.029 |

| Men | 3.35 | 3.33 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 0.85 |

| Behavior Areas | Place of Residence | M | Me | Q1 | Q3 | SD | H, p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchasing activity enhanced by visual identification (Area I) | (I) village | 2.36 | 2.33 | 1.83 | 2.83 | 0.78 | H= 6.295 p = 0.098 |

| (II) city ≤ 50,000 residents | 2.39 | 2.33 | 1.83 | 3.00 | 0.76 | ||

| (III) city 50,000–500,000 residents | 2.61 | 2.67 | 2.00 | 3.17 | 0.88 | ||

| (IV) city ≥ 500,000 residents | 2.45 | 2.50 | 1.83 | 3.00 | 0.83 | ||

| Sustainable consumption (Area II) | (I) village | 2.65 | 2.60 | 2.00 | 3.20 | 0.90 | H= 11.399 p = 0.010 I < IV |

| (II) city ≤ 50,000 residents | 2.69 | 2.60 | 2.20 | 3.20 | 0.86 | ||

| (III) city 50,000–500,000 residents | 2.92 | 3.00 | 2.20 | 3.60 | 0.91 | ||

| (IV) city ≥ 500,000 residents | 2.86 | 2.80 | 2.20 | 3.40 | 0.84 | ||

| Behaviors stimulated by legal regulations and economic factors (Area III) | (I) village | 3.52 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 0.77 | H = 13.853 p = 0.003 I > IV III > IV |

| (II) city ≤ 50,000 residents | 3.46 | 3.33 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 0.81 | ||

| (III) city 50,000–500,000 residents | 3.57 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 4.33 | 0.92 | ||

| (IV) city ≥ 500,000 residents | 3.29 | 3.33 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 0.89 |

| Behavior Areas | Income | M | Me | Q1 | Q3 | SD | H, p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchasing activity enhanced by visual identification (Area I) | (I) ≤PLN 1000 (EUR 221) | 2.60 | 2.50 | 1.83 | 3.33 | 0.95 | H = 2.683 p = 0.44(3 |

| (II) PLN 1000–2000 (EUR 222–441) | 2.47 | 2.42 | 1.83 | 3.00 | 0.84 | ||

| (III) PLN 2000–3000 (EUR 442–662) | 2.43 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 2.83 | 0.73 | ||

| (IV) ≥ PLN 3000 (EUR 663) | 2.39 | 2.33 | 1.67 | 3.00 | 0.83 | ||

| Sustainable consumption (Area II) | (I) ≤PLN 1000 (EUR 221) | 3.03 | 3.00 | 2.20 | 3.80 | 0.98 | H = 10.913 p = 0.012 I > IV |

| (II) PLN 1000–2000 (EUR 222–441) | 2.82 | 2.80 | 2.20 | 3.60 | 0.87 | ||

| (III) PLN 2000–3000 (EUR 442–662) | 2.80 | 2.80 | 2.20 | 3.40 | 0.81 | ||

| (IV) ≥ PLN 3000 (EUR 663) | 2.66 | 2.60 | 2.00 | 3.20 | 0.90 | ||

| Behaviors stimulated by legal regulations and economic factors (Area III) | (I) ≤PLN 1000 (EUR 221) | 3.41 | 3.33 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 0.90 | H = 0.976 p = 0.807 |

| (II) PLN 1000–2000 (EUR 222–441) | 3.48 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 0.80 | |||

| (III) PLN 2000–3000 (EUR 442–662) | 3.41 | 3.33 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 0.83 | ||

| (IV) ≥PLN 3000 (EUR 663) | 3.40 | 3.33 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 0.90 |

| Reply Based Groups | H | p | Differences Between Groups | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Don’t Know this App | I Know this App but I Don’t Use it | I Know This App and I Use it | ||||||||||

| M | Me | SD | M | Me | SD | M | Me | SD | ||||

| GdzieWyrzucić | ||||||||||||

| Area I | 2.329 | 2.333 | 0.764 | 2.552 | 2.500 | 0.773 | 3.133 | 3.083 | 0.915 | 50.977 | 0.000 | I < II, I < III, II < III |

| Area II | 2.684 | 2.600 | 0.836 | 2.959 | 3.000 | 0.877 | 3.251 | 3.200 | 0.955 | 27.634 | 0.000 | I < II, I < III |

| Area III | 3.363 | 3.333 | 0.864 | 3.444 | 3.500 | 0.768 | 3.847 | 4.000 | 0.792 | 20.710 | 0.000 | I < III, II < III |

| Vinted | ||||||||||||

| Area I | 2.481 | 2.333 | 1.031 | 2.320 | 2.333 | 0.751 | 2.541 | 2.500 | 0.778 | 13.433 | 0.0012 | II < III |

| Area II | 2.712 | 2.600 | 0.904 | 2.624 | 2.600 | 0.821 | 2.951 | 3.000 | 0.881 | 24.089 | 0.000 | I < III, II < III |

| Area III | 3.368 | 3.333 | 0.864 | 3.331 | 3.333 | 0.854 | 3.523 | 3.667 | 0.842 | 10.462 | 0.0053 | II < III |

| Veturilo | ||||||||||||

| Area I | 2.470 | 2.500 | 0.791 | 2.335 | 2.333 | 0.805 | 2.546 | 2.500 | 0.833 | 8.501 | 0.0143 | II < III |

| Area II | 2.56 | 2.600 | 0.859 | 2.684 | 2.600 | 0.838 | 3.049 | 3.000 | 0.859 | 36.2178 | 0.000 | I < III, II < III |

| Area III | 3.469 | 3.667 | 0.824 | 3.367 | 3.333 | 0.862 | 3.453 | 3.333 | 0.863 | 2.573925 | 0.2761 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaska, E.; Werenowska, A.; Balińska, A. Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Behaviors of Generation Z in Poland Stimulated by Mobile Applications. Energies 2022, 15, 7904. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15217904

Jaska E, Werenowska A, Balińska A. Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Behaviors of Generation Z in Poland Stimulated by Mobile Applications. Energies. 2022; 15(21):7904. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15217904

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaska, Ewa, Agnieszka Werenowska, and Agata Balińska. 2022. "Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Behaviors of Generation Z in Poland Stimulated by Mobile Applications" Energies 15, no. 21: 7904. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15217904

APA StyleJaska, E., Werenowska, A., & Balińska, A. (2022). Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Behaviors of Generation Z in Poland Stimulated by Mobile Applications. Energies, 15(21), 7904. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15217904