Energy Transition of the Coal Region and Challenges for Local and Regional Authorities: The Case of the Bełchatów Basin Area in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A special role in the energy transition process is attributed to the public authorities as responsible for moderating/stimulating actions that limit the possible social, economic, spatial, and environmental consequences of the transition;

- The ability of public administration (in particular the local and regional authorities) to implement energy policies that protect the global public interest is one of the most important conditions for the transition to succeed;

- The complexity of the challenges faced by Bełchatów and its functional area requires the implementation of integrated activities, involving various types of stakeholders. Taking joint and integrated projects is crucial for an effective transformation process;

- The energy transition requires favourable conditions in the organisational, legal, institutional, financial, and psychosocial spheres, allowing for the involvement of various actors representing the public and private sectors, and social partners, who will jointly create a network of institutions working together towards an effective transition. The limitations in cooperation hinder this process.

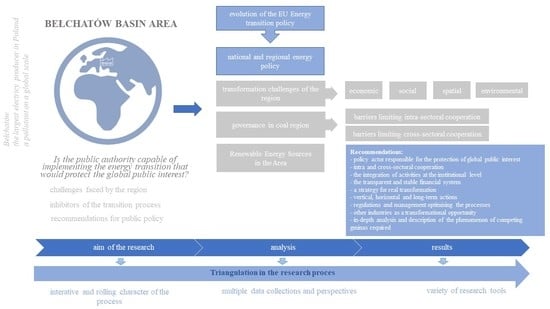

2. Materials and Methods

3. Literature Review

3.1. European Energy and Climate Policy Framework

3.2. National Energy Policy

- no more than 56% of coal in electricity generation in 2030;

- at least 23% of RES in gross final energy consumption in 2030;

- implementation of nuclear energy in 2033;

- a 30% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 (compared to the 1990 level);

- a 23% reduction in primary energy consumption by 2030 (compared to the 2007 consumption projections).

- Just Transition—focusing on the regions and communities most affected by the negative effects of the low-carbon energy transition, i.e., the post-coal regions. With the obtained support, new jobs and new industries participating in the transformation of the sector can be created. It is vital to involve various public and economic entities in these activities, as well as individual energy consumers who will actively participate in the energy market. The fair manner of transformation will be ensured (it will not leave anyone behind), and the principle of participation will be fulfilled (i.e., grassroots transition conducted locally);

- zero-emission energy system—a long-term objective to be achieved through the implementation of offshore nuclear and wind energy, the increase in the role of distributed and civic energy, the involvement of industrial energy, while at the same time ensuring energy security;

- good air quality—visible improvement in air quality and its effect on public health. It is the most noticeable sign of a shift away from fossil fuels. The implemented investments will transform the heating sector (systemic and individual), electrification of transport, and the promotion of passive and zero-emission houses using local energy sources.

- people and communities—facilitating employment opportunities and reskilling, improving energy-efficient housing and fighting energy poverty;

- companies—making the transition to low-carbon technology attractive for investment, providing financial support for and investment in research and innovation;

- member states or regions—investing in new green jobs, sustainable public transport, digital connectivity and clean energy infrastructure [59].

4. Results

4.1. The Bełchatów Basin Area in Regional Planning and Strategic Documents

4.2. The Economic, Social, and Spatial Effects of Mining Activities in the Bełchatów Mining Area

4.2.1. Characteristics and Economic Effects of Mining Activities

4.2.2. Characteristics and Social Effects of Mining Activities

4.2.3. Characteristics, Spatial and Environmental Effects of Mining Activities

4.3. Local and Regional Determinants in the Transformation of the Bełchatów Basin

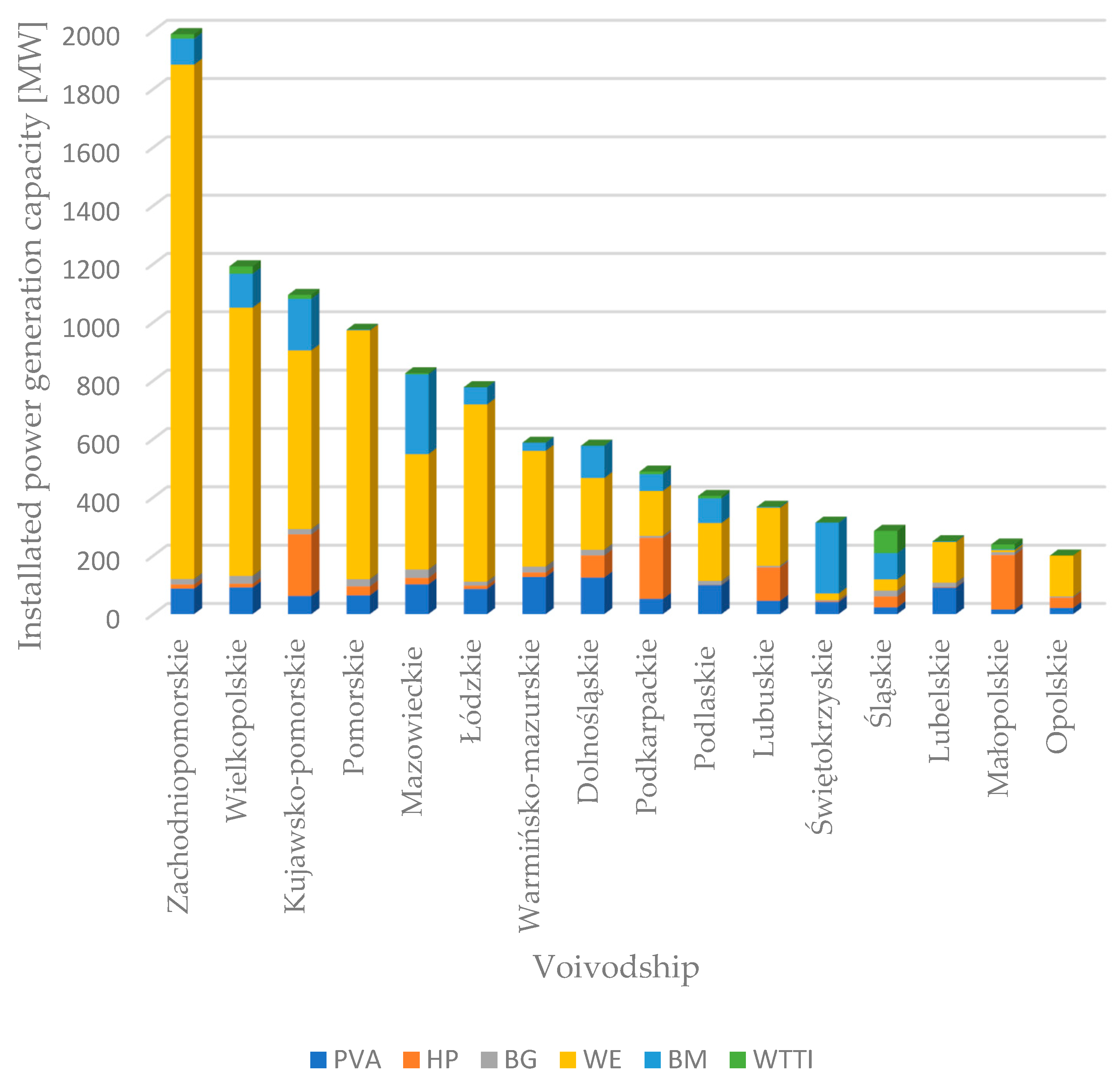

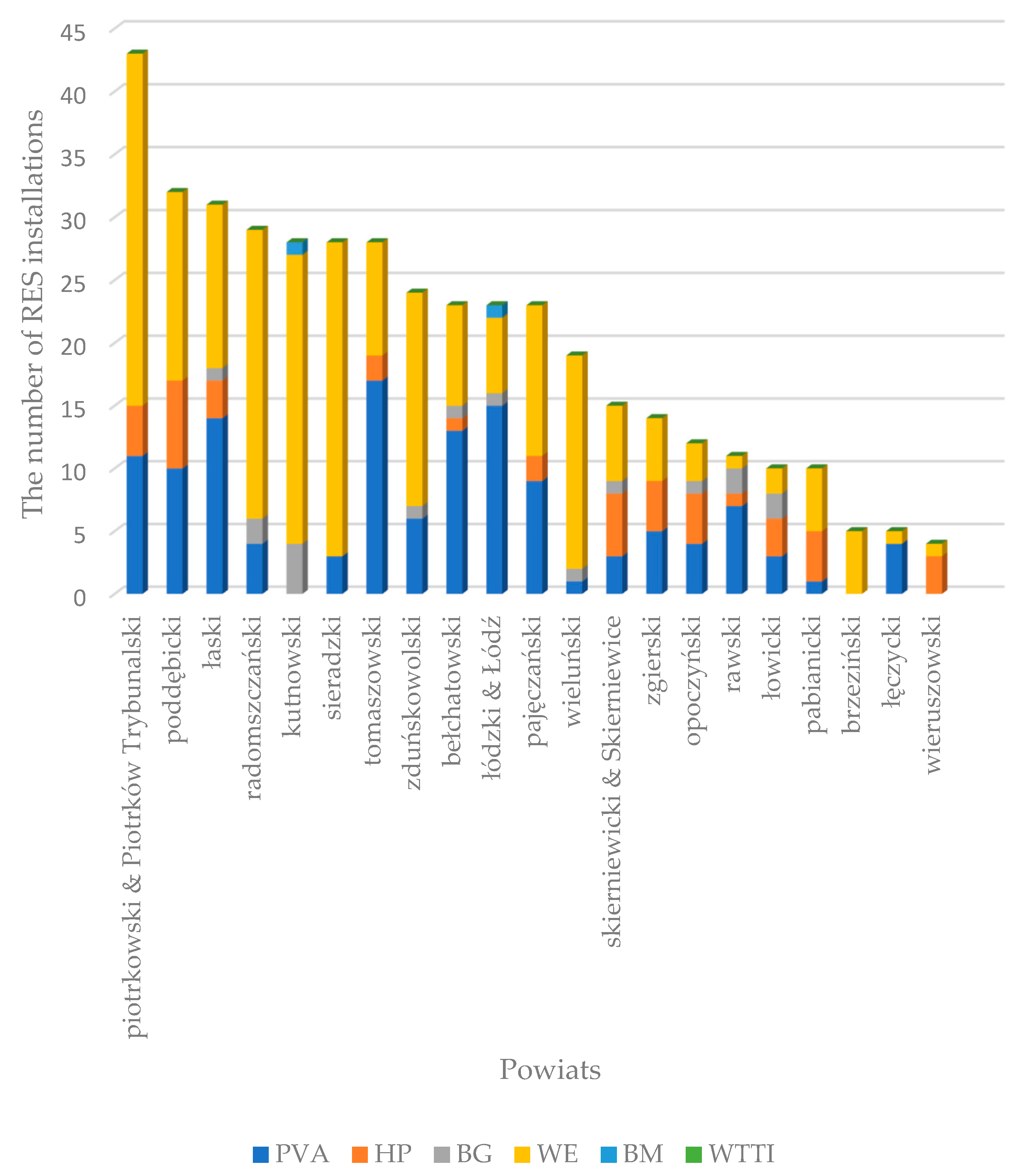

4.3.1. Renewable Energy Sources in the Bełchatów Area

4.3.2. The Barriers Limiting Cooperation and Influencing the Energy Transition Process

The Barriers Limiting Intra-Sectoral Cooperation

The Barriers Limiting Cross-Sectoral Cooperation

4.3.3. Local Initiatives in the Bełchatów Basin Area

- launch new open pit sites, by securing areas in the vicinity of the planned pit against the impact of the forecasted depression cone, and by expanding the infrastructure to service the mine’s facilities, resettlements, expansion of operations;

- reduce the emission of gaseous and particulate pollutants into the atmosphere by participating in programmes aimed at replacing central heating boilers with new and environmentally friendly ones, and building or expanding the heating network;

- develop electricity generation based on renewable sources, including the use of solar, hydro, and wind energy;

- reclaim the degraded earth, soil, and water by regulating water relations and restoring vegetation;

- improve transport to facilitate external and internal accessibility of the area;

- create and develop industrial and economic zones;

- develop green industries and RES services;

- adapt local education to the needs of the predominant economic trends in the area;

- expand the water supply and sewage networks.

- development of mine-related infrastructure;

- reduction in the emission of gaseous and particulate pollutants into the atmosphere by implementing programmes aimed at replacing central heating boilers with new ecological ones and expanding/building the gas network;

- electricity generation based on renewable sources, including the use of solar, hydro, and wind energy;

- reclamation of the degraded earth, soil, and water by regulating water relations, restoration of soil and vegetation for leisure, conference, and business tourism, and generation of electricity from RES;

- reducing noise pollution;

- support for agricultural activities, particularly considering the dryness of the soil and the decrease in the groundwater level (surface water deficit);

- improving the internal and external transport accessibility of the area;

- creation and development of parks and industrial eco-parks;

- other areas, including renovations and expansion of schools, and of water supply and sewage networks.

4.4. The Theory of Government Failure and the Implementation of Energy and Climate Policy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- production investments in the SMEs sector, leading to economic diversification, modernisation and restructuring;

- investing in the generation of new enterprises;

- investing in research and innovation activities (including those carried out by universities and public research institutions), supporting the transfer of advanced technologies;

- investing in technologies, systems and infrastructures providing affordable clean energy;

- investing in renewable energy and energy efficiency;

- investing in smart and sustainable local mobility;

- renovation and modernisation of heating networks;

- investing in digitalisation, digital innovation and digital connectivity;

- investing in regeneration, decontamination and restoration of degraded areas, and in green infrastructure;

- promotion of a circular economy;

- upskilling and reskilling of staff and jobseekers (including job search assistance).

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kryk, B.; Guzowska, M.K. Implementation of Climate/Energy Targets of the Europe 2020 Strategy by the EU Member States. Energies 2021, 14, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Development Strategy of the Lodzkie Region 2030. Appendix. In Proceedings of the Resolution No. XXX/414/21 of the Regional Assembly of the Lodzkie Voivodship, Lodz, Poland, 6 May 2021.

- Danielewicz, J. Integrated Management of Metropolitan Areas in Romania. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oeconomica 2020, 6, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, A.; Rzeńca, A.; Sobol, A. Place-Based Policy in the “Just Transition” Process: The Case of Polish Coal Regions. Land 2021, 10, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Jurkiewicz, M.; Czarnecka, M.; Kinelski, G.; Sadowska, B.; Bilińska-Reformat, K. Determinants of Decarbonisation in the Transformation of the Energy Sector: The Case of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmochowska-Dudek, K.; Wójcik, M. Socio-Economic Resilience of Poland’s Lignite Regions. Energies 2022, 15, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawchenko, T.A.; Gordon, M. Just Transitions for Oil and Gas Regions and the Role of Regional Development Policies. Energies 2022, 15, 4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdż, W.; Mróz-Malik, O.; Kopiczko, M. The Future of the Polish Energy Mix in the Context of Social Expectations. Energies 2021, 14, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.Z.; Kurtyka, M.; Tchorek., G. (Eds.) Energy and Climate Transformation–Chosen Dilemmas and Recommendations; Warsaw University Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Markowski, T. Territorial capital as a goal of integrated development planning. In Mazovia Regional Studies; Cieślak, A., Ed.; Mazowieckie Biuro Planowania Regionalnego w Warszawie: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; No. 18; p. 115. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Żak-Skwierczyńska, M. Cooperation Barriers between Government Units of Urban Functional Areas. Example of the Lodzkie Region; Lodz University Press: Lodz, Poland, 2018. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and „Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university-industry-government Relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other? A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 1, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, O.; Monteiro, S.; Thompson, M. A growth model for the quadruple helix. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2012, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Barth, T.D.; Campbell, D.F.J. The Quintuple Helix innovation model: Global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Qualitative Research Methods; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; Volume 1, p. 640. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jemielniak, D. Qualitative Research; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; Volume 2, p. 24. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching; Sage: London, UK, 1996; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research; Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1992.

- Agenda 21. Available online: sustainabledevelopment.un.org (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- 10 UNFCCC, Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1998.

- Burchard-Dziubińska, M. Adaptation of urban areas to climate change. In EcoCity#Environment. Sustainable, Smart and Participatory Development of the City; Rzeńca, A., Ed.; Lodz University Press: Lodz, Poland, 2016; pp. 143–163. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Koczan, M. Shaping Objectives of Energy and Climate Policy of the European Union until 2030. Conseq. Pol. East. Stud. 2020, 14, 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2009/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 Amending Directive 2003/87/EC So as to Improve and Extend the Greenhouse Gas Emission Allowance Trading Scheme of the Community (EU ETS Directive); European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2009.

- Decision No 406/2009/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Effort of Member States to Reduce Their Greenhouse Gas Emissions to Meet the Community’s Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Commitments up to 2020 (Non-ETS Decision); European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2009.

- Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2000.

- Directive 2001/80/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2001 on the Limitation of Emissions of Certain Pollutants into the Air from Large Combustion Plant; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2001.

- Directive 2004/35/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on Environmental Liability with Regard to the Prevention and Remedying of Environmental Damage; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2004.

- Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 November 2005 on the Mobilisation of the European Union Solidarity Fund According to Point 3 of the Interinstitutional Agreement of 7 November 2002 between the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission on the Financing of the European Union Solidarity Fund Supplementing the Interinstitutional Agreement of 6 May 1999 on Budgetary Discipline and Improvement of the Budgetary Procedure; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2006.

- Directive 2008/1/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 January 2008 Concerning Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2008.

- Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2006 on Shipments of Waste; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2006.

- Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Subsequently Repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC (OZE Directive); European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2009.

- Communication from the Commission, Action Plan for Energy Efficiency: Realising the Potential, Brussels, COM(2006)545 Final; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2006.

- Communication from the Commission, EUROPE 2020. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, Brussels, COM(2010) 2020; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2020.

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Energy Efficiency Plan 2011, Brussels, COM(2011) 109 Final; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2011.

- White Paper, Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area—Towards a Competitive and Resource Efficient Transport System, Brussels, COM(2011) 144 Final; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Roadmap for the Transition to a Competitive Low-Carbon Economy in 2050, Brussels 9/03/2011, COM (2011) 112; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Energy Roadmap 2050, Brussels 15.12.2011, COM(2011) 885 Final; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Conclusions on Energy, European Council, 4 February 2011, I Point 15; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2011.

- European Commission. Green Paper A 2030 Framework for Climate and Energy Policies; COM(2013) 169 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Policy Framework for Climate and Energy in the Period from 2020 to 2030, Brussels, 28.1.2014, COM(2014) 15 Final/2; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions, and the European Investment Bank. Clean Energy for All European, Brussels, 30.11.2016, COM(2016) 860 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Kucharska, A. Energy Transition. Challenges for Poland in the Light of the Experience of Western European Countries; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; p. 89. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. The European Green Deal, Brussels, 11.12.2019, COM(2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Energy and the Green Deal. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/energy-and-green-deal_en (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Fit for 55. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/fit-for-55-the-eu-plan-for-a-green-transition/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- More: European Climate Pact. Available online: https://climate-pact.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- European Climate Pact. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/european-green-deal/european-climate-pact_en (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Climate Neutrality: Council Adopts the Just Transition Fund. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2021/06/07/climate-neutrality-council-adopts-the-just-transition-fund/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- National Energy and Climate Plan for the Years 2021–2030; Ministry of State Asset: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. (In Polish)

- The 2030 Strategy for Sustainable Development of Transport; Council of Ministers: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. (In Polish)

- The 2030 National Environmental Policy—The Development Strategy in the Area of the Environment and Water Management; Council of Ministers: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. (In Polish)

- The 2030 Strategy for Sustainable Development of Villages, Agriculture and Fisheries; Council of Ministers: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. (In Polish)

- Energy Policy of Poland until 2040; Annex to Resolution No. 22/2021 of the Council of Ministers of 2nd Warsaw; Ministry of Climate and Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. (In Polish)

- Strategy for Responsible Development for the Period up to 2020 (Including the Perspective up to 2030), Poland; Council of Ministers: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. (In Polish)

- More: The Just Transition Mechanism: Making Sure No One Is Left Behind. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism_en (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- The Development Strategy of the Lodzkie Region, Lodzkie Region; Marshal’s Office of the Lodzkie Region: Lodz, Poland, 2013.

- The Spatial Development Plan for the Lodzkie Region and the Spatial Development Plan of the Urban Functional Area of Lodz, Adopted on 28.08.2018 by Resolution No. LV/679/18 of the Sejmik of the Lodzkie Region. Available online: https://bip.lodzkie.pl/urzad-marszalkowski/programy/item/7929-nowy-plan-zagospodarowania-przestrzennego-wojew%C3%B3dztwa (accessed on 8 August 2022). (In Polish).

- Act of 6 December 2006 on the Principles of Conducting Development Policy; Journal of Laws 2006 No. 227, Item 1658, as Amended, Last Amendments in Journal of Laws 2021, Item 1057; Journal of Laws: Warsaw, Poland, 2006.

- Schmitz, H. Collective Efficiency: Growth Path for Small Scale. J. Dev. Stud. 1995, 31, 529–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Territorial Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2001.

- European Commission. Territorial State and Perspectives of the European Union, towards a Stronger European Territorial Cohesion in the Light of the Lisbon and Gothenburg Ambitions Scoping Document and Summary of Political Messages, Luxembourg; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R. Regional competitiveness: Towards a concept of territorial capital. In Modelling Regional Scenarios for the Enlarges Europe, European Competitivenes and Global Strategies; Capello, R., Camagni, R., Chizzolini, B., Fratesi, U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; van Broekhuizen, R.; Brunori, G.; Sonnino, R.; Knickel, K.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Oostindie, H. Towards a framework for understanding regional rural development. In Unfolding Webs: The Dynamics of Regional Rural Development; van der Ploeg, J.D., Marsden, T., Eds.; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R. Territorial capital and regional development. In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories; Capello, R., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Regional competitiveness and territorial capital: A conceptual approach and empirical evidence from the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaucha, J.; Brodzicki, T.; Ciołek, D.; Komornicki, T.; Mogiła, Z.; Szlachta, J.; Zaleski, J. Territorial Dimension of Growth and Development; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, B.I. Territorial Capital: Theory, Empirics and Critical Remarks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1327–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudłacz, T.; Markowski, T. The territorial capital of urban functional areas as a challenge for regional development policy: An outline of the concept. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2018, 2, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Territorial Plan for the Just Transition of the Lodzkie Region (draft), Appendix No. 1. In Proceedings of the Resolution 189/22 of the Regional Assembly of the Lodzkie Voivodship, Łódź, Poland, 14 March 2022.

- National Just Transition Plan (Draft). 2022; Not published.

- Report on the State of Natural Environment in the Lodzkie Voivodeship; The Regional Inspectorate of Environmental Protection: Lodz, Poland, 2018.

- Sovacool, B.K. How long will it take? Conceptualizing the temporal dynamics of energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.; Budhwar, P.; Wood, G. Long-term energy transitions and international business: Concepts, theory, methods, and a research agenda. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/oze/potencjal-krajowy-oze (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Amankwah-Amoah, J. Solar energy in sub-Saharan Africa: The challenges and opportunities of technological leapfrogging. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 57, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallbäck, J.; Gabrielsson, P. Entrepreneurial marketing strategies during the growth of international new ventures originating in small and open economies. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 22, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T.; Hart, S.L. Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the transnational model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.B.; Leca, B.; Zilber, T.B. Institutional work: Current research, new directions and overlooked issues. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, I.; Langlois, L. Energy indicators for sustainable development. Energy 2007, 32, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; Iles, A.; Jones, C.F. The social dimensions of energy transitions. Sci. Cult. 2013, 22, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reports and Articles. Available online: https://grantthornton.pl/raporty-i-artykuly/ (accessed on 26 August 2022). (In Polish).

- Regulski, J. Self-Governing Poland; Rosner and Co.: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; pp. 88–89. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Dobrołowicz, W. Psychology and Barriers; Wydawnictwo Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1993; p. 52. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Markowski, T. Subjective and objective competitiveness of regions, Committee for Spatial Economy and Regional Planning. Pol. Acad. Sci. Bull. 2005, 2005, 219. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Local Action Groups in Lodzkie Region. Available online: https://www.lodzkie.pl/leader/lgd-w-wojew%C3%B3dztwie-%C5%82%C3%B3dzkim (accessed on 30 August 2022). (In Polish).

- Dollery, B.F.; Wallis, J.L. Market failure, Government failure leadership and public policy. Public Manag. 2009, 2, 83. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. Government Failure and the Spatial Management System; Studia KPZK PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; p. 175. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Markowski, T. Territorial dimension dilemmas in the national and regional strategic documents. In The National Regional Development Strategy until 2020 and the Strategies of Socio-Economic Development of Voivodeships; Szlachta, J., Woźniak, J., Eds.; Studia KPZK PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; p. 137. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Demirbas, D.; Demirbas, S. Role of the State in Developing Countries: Public Choice versus Schumpeterian Approach. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 2, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, D.C. Public Choice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Self, P. Government by the Market? The Politics of Public Choice; Macmillan: Shanghai, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Drzazga, D. Systemic Determinants of Spatial Planning as an Instrument for Achieving Sustensive Development; Lodz University Press: Lodz, Poland, 2018. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Who We Are. Available online: https://pgegiek.pl/O-firmie/Kim-jestesmy (accessed on 1 September 2022). (In Polish).

- Bass, A.E.; Grøgaard, B. The long-term energy transition: Drivers, outcomes, and the role of the multinational enterprise. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J. Integrated development planning and local spatial policy tools. J. Econ. Manag. 2020, 41, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozowska, S.; Wendt, J.A.; Tomaszewski, K. The Challenges of Poland’s Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 8165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, C.M. Trade, Climate and Energy: A New Study on Climate Action through Free Trade Agreements. Energies 2021, 14, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy. A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations, Independent Report Prepared at the Request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy by Fabrizio Barca; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dobravec, V.; Matak, N.; Sakulin, C.; Krajačić, G. Multilevel governance energy planning and policy: A view on local energy initiatives. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specific Objective | Strategic Project (to Achieve the Objective) |

|---|---|

| 1—Optimal use of own energy resources | 1—Transformation of coal regions |

| 2—Expansion of electricity generation and grid infrastructure | 2A—Capacity market 2B—Implementation of smart grids |

| 3—Diversification of supply and development of network infrastructure for natural gas, crude oil, and liquid fuels | 3A—Construction of the Baltic Pipe 3B—Construction of Line2 of the Pomeranian Pipeline |

| 4—Development of energy markets | 4A—Implementation of the Action Plan (to increase cross-border electricity transmission capacity) 4B—Gas Hub 4C—Development of electromobility |

| 5—Introduction of nuclear power | 5—Polish Nuclear Power Programme |

| 6—Development of renewable energy sources | 6—Implementation of offshore wind energy |

| 7—Development of district heating and co-generation | 7—Development of district heating |

| 8—Improvement of energy efficiency | 8—Promoting energy efficiency improvement |

| Economic Transformation | Social Transformation | Spatial Transformation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges: |

|

|

|

| Operational objective: | OO1 a competitive, innovative, and climate-neutral economy based on smart growth, diversified industry modern technologies, and attractive jobs | OO2 a qualified, informed, and actively involved society, with equal access to high-quality public services | OO3 space with high-quality natural environment and landscape, guaranteeing adaptation to climate change and characterised by good transport accessibility |

| Results: |

|

|

|

| Barriers | Intra-Sectoral Cooperation | Cross-Sectoral Cooperation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurs | NGOs | Universities Scientific and Research Units | ||

| Development and planning barriers | x | |||

| Institutional barriers | x | x | x | |

| Legal, formal and systemic restrictions | x | x | x | |

| Financial barriers | x | x | ||

| Politicisation | x | x | ||

| Psychological barriers | x | x | x | |

| Interpersonal barriers | x | |||

| Low quality of social capital | x | |||

| Lack of common goals | x | |||

| Barriers impending the development policy and building relations | x | x | x | x |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Żak-Skwierczyńska, M. Energy Transition of the Coal Region and Challenges for Local and Regional Authorities: The Case of the Bełchatów Basin Area in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 9621. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15249621

Żak-Skwierczyńska M. Energy Transition of the Coal Region and Challenges for Local and Regional Authorities: The Case of the Bełchatów Basin Area in Poland. Energies. 2022; 15(24):9621. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15249621

Chicago/Turabian StyleŻak-Skwierczyńska, Małgorzata. 2022. "Energy Transition of the Coal Region and Challenges for Local and Regional Authorities: The Case of the Bełchatów Basin Area in Poland" Energies 15, no. 24: 9621. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15249621

APA StyleŻak-Skwierczyńska, M. (2022). Energy Transition of the Coal Region and Challenges for Local and Regional Authorities: The Case of the Bełchatów Basin Area in Poland. Energies, 15(24), 9621. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15249621