Abstract

Background. Laws that enable a circular economy (CE) are being enacted globally, but reliable standardized and digitized CE data about products is scarce, and many CE platforms have differing exclusive formats. In response to these challenges, the Ministry of The Economy of Luxembourg launched the Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative to develop a globalized open-source industry standard to allow the exchange of standardized data throughout the supply cycle, based on these objectives: (a) Provide basic product circularity data about products. (b) Improve circularity data sharing efficiency. (c) Encourage improved product circularity performance. A policy objective was to have the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) voted to create a working group. Methods. A state-of-play analysis was performed concurrently with consultations with industry, auditors, data experts, and data aggregation platforms. Results. Problem statements were generated. Based on those, a solution called Product Circularity Data Sheet (PCDS) was formulated. A proof of concept (POC) template and guidance were developed and piloted with manufacturers and platforms, thus fulfilling objective (a). For objective (b), IT ecosystem requirements were developed, and aspects are being piloted in third party aggregation platforms. Objective (c) awaits implementation of the IT ecosystem. The policy objective related to the ISO was met. Conclusions and future research. In order to fully test the PCDS, it is necessary to: conduct more pilots, define governance, and establish auditing and authentication procedures.

1. Introduction

Concepts for a circular economy (CE) are being introduced widely in order to assure supply and use of materials and energy without compromising the needs of future generations. Digitalization is one tool being studied to implement the CE [1]. Digital twins are being commonly used to digitally represent physical products [2]. These provide diverse data, mostly focusing on product performance and technical properties. For example, in the construction sector, digital twins for products and building elements are incorporated into Building Integrated Management (BIM) software as BIM Objects [3,4]. Environmental properties are sometimes added to digital twins for products. One question arising from this evolution of digital twins is, which types of data do these require in order to reflect circular economy characteristics and metrics? A 2020 United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) financial institutions survey examined this question after extensively reviewing CE literature and conducting a survey of financial institutions.

“Findings from UNEP FI’s survey show that financial institutions responding prioritized the following non-financial data needed for the integration of circularity:

As described under Materials and Methods, the focus in this article is on the first dataset in the list. A prerequisite for gathering the data for such a metric is to define the CE in order to identify which data to collect. However, a universally accepted definition of the CE does not exist. Kirchherr et al. [6] and Corvellec et al. [7] reported a diversity of definitions. Owing to this diversity, different CE metrics and data standards for products are being developed, as described further under Problem statements arising from State-of-Play Analysis. For example, a Digital Product Passport (DPP) is being developed by the European Commission (EC), which recently published draft regulations for DPPs as part of its framework for upgrading eco-design requirements for sustainable products and the CE [8]. Adisorn et al. described many of the complexities associated with an earlier version of the DPP proposal [9]. As well, different types of “Materials Passport” and “Product Passport” have been introduced. Hansen et al. described materials passports and potential criteria beginning in 2012 [10], and again in 2020 [11]. Heinrich et al. [12] proposed potential CE and sustainability criteria for a materials passport, citing various schemes. See Supplementary Materials S1, State-of-play analysis, for references to other initiatives. Some passports cover functional characteristics of products [13]. The EU Horizon 2020 Buildings as Materials Banks (BAMB) initiative [14] published working papers, reports, and proof-of-concept platforms for a materials passport [15]. To start, in 2016, BAMB conducted a state-of-the-art study, summarizing different passport schemes. The work included cross referencing criteria contained in each scheme [16]. Other literature reviews [17] concluded that there is no widely accepted definition for those passports. Due to this diversity, standardized data on basic circularity characteristics are not broadly available to manufacturers, data aggregation platforms, and customers. Especially Micro-Small-to-Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), which constitute the majority of manufacturers globally [18], face the prospect of having to distribute different datasets in diverse formats to various product platforms and customers. Similar barriers to MSMEs entering the CE are described by Mishra et al. and include an absence of technical support to MSMEs by regulators [19]. Trade secrets also hinder transparency. Connected to these is a growing concern that A.I.-supported data gathering could infringe on those secrets [20]. This highlights the need for robust data security. In the wider environmental regulatory field governing sustainability data such as product composition, there is evidence that current regimes are not working well. These could affect accuracy of reporting for the CE. For example, one study describes how the Regulation for Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) is violated regularly in products sold in the EU [21]. These violations make it problematic to reliably evaluate the safety of products for use, reuse and recycling in the CE. There is also erroneous reporting in Safety Data Sheets (SDS) [22], which are used globally. These trends indicate the need for a robust authentication system for CE data. Altogether, the aforementioned challenges present barriers to scaling up CE data exchange. An example of an attempt to deal with these was a BAMB materials passport work package [23] led by the institute EPEA [24], based on the Product Circularity Passport™ developed earlier by EPEA [25]. On completion of the BAMB materials passport work package, a report by Luscuere et al. recommended that “A standardized data format for communicating product information …would make the implementation much safer and faster” [26]. In 2018, the Ministry of the Economy of Luxembourg launched the Circularity Dataset Initiative [27] to start solving this and other CE metric challenges described previously. Moreover, the initiative was launched to further the aim by the government of Luxembourg for the country to become a business and data hub for the CE [28]. The earlier referenced BAMB materials passport report by Luscuere et al. cited the initiative as one effort to implement BAMB recommendations [29]. The initial public tender to support the initiative was awarded to the CE consultancy company PositiveImpaKT [30], located in Luxembourg. Later in the process, additional guidance was provided by the Luxembourgish National Standardization Body ILNAS [31].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hypothesis and Objectives

The hypothesis co-developed by the Ministry of the Economy and its external advisors, was that a decentralized, open-source template containing basic CE criteria, and supported by standardized CE definitions and data protocols for products, could facilitate the exchange of CE metrics globally. The following objectives arising from the hypothesis were formulated, then validated with stakeholders as part of the process described in the next section:

- Provide basic circularity data on products.

- Improve circularity data sharing efficiency for products.

- Encourage improved product circularity performance [32].

2.2. Process

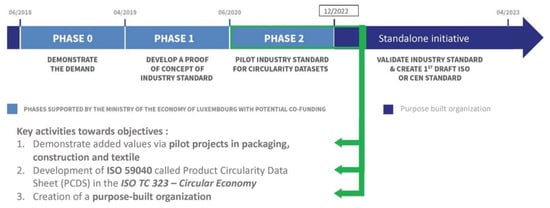

The Ministry organized a stakeholder recruitment and collaboration process to set up working groups, validate objectives, scope, and CE definition, then develop and pilot a PCDS template model and guidance document. The process was designed to be supported and tested by stakeholders as a basis for developing a global standard. The first two phases were focused on content and process leading to creation of a PCDS template and guidance. The third is focused on ecosystem infrastructure, auditing procedures and adoption of a standard by the ISO. This article covers the first two phases. For further description of the model developed during the consultation process, refer to Overview of the PCDS model.

A Phase 0 analysis was conducted with the objective of determining whether there was sufficient interest among manufacturers and other potential users to explore a simplified circularity dataset. The decision by the Ministry of the Economy on whether to move forward was based on whether a volunteer group composed of key stakeholders could be assembled to co-develop and test a CE dataset. An initial group of 30 was assembled from among companies who had participated in other CE projects, including Ministry of the Economy projects, activities of CE consultancies including PositiveImpaKT and the institute EPEA [33], as well as some BAMB participants. The group expanded to about 50 members throughout the project as the initiative became better known. See Supplementary materials S1 for a more specific description of stakeholders. The main stakeholders identified to participate in the working groups were manufacturers at the product assembly stage, and 1st and 2nd tier suppliers of component and material products for those assembled products. Other potential stakeholders included users such as distributors, retailers, and recyclers, as well as data aggregation and product certification platforms. Auditors were included for their experience auditing standards compliance. Policymakers and standards groups with an interest in the CE were also consulted, as the PCDS template could provide data to fulfill CE policy and standards requirements. For example, the initiative aimed to inform the CE standards process initiated with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) [34].

An ad hoc structure was set up consisting of a 4-member Dataset Supervisory Group, a ~15 member Data Working Group (DWG), as well as a broader ~35-member Stakeholder Group (SG) to provide feedback. A partial list of SG participants is published on the PCDS website that was established during this process [35]. CE expertise within the DWG and SG included authors of the national circular economy blueprint for Luxembourg [36] and follow-up studies [37], representatives from EPEA, companies that designed and sold products designed according to various CE criteria, and participants from BAMB. Representatives of platforms that were selling CE services, including Cobuilder in France [38], Madaster in Netherlands [39], Toxnot in the U.S. [40], and Cradle to Cradle Product Innovation Institute in the U.S. and Europe [41] were consulted, although some were not in the SG itself. In 2020, the Luxembourgish state agency InCert [42] was also engaged by the Ministry to work on the IT infrastructure. While and after the PCDS group was assembled, the work was divided into two generally sequential but sometimes overlapping segments, Problem Statements, and Solution Development. In order to develop these, a series of online surveys, workshops, and one-on-one consultations were held, and from those a basic PCDS and Guidance were drafted. Then, manufacturers and their suppliers tested the PCDS with one of their products and provided feedback. The feedback was used to optimize an early PCDS version. In 2020, the Ministry of the Economy published a report in collaboration with PositiveImpaKT and some authors of this article [43]. Amended excerpts from that report are provided in Supplementary Materials S1. From that report, plans for the next steps were developed. Updates to the PCDS are planned as a result of feedback from that process.

2.3. Selecting a CE Definition

The initiative faced the challenge of aligning diverse CE and other nomenclature, starting with a CE definition. In the absence of a globally accepted definition, the Dataset Supervisory Group selected the following extensively cited definition, which was later validated with stakeholders.

“The Circular Economy is characterized as an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design and which aims to keep products, components and materials at their highest utility and value at all times, distinguishing between technical and biological cycles” [44].

The cycles were adapted from the Cradle-to-Cradle design protocol [45], which was also defined more specifically for the built environment [46]. The protocol provided added guidance for interpreting the CE definition for the PCDS.

2.4. Scope

From previous inventories, three categories of CE-relevant passports were identified in the market: (a) buildings and building elements, (b) products, (c) constituent materials. The PCDS scope was focused on the product scale rather than the building scale, as products are basic units of commerce for all sectors. (The term “product” is described in the nomenclature). The PCDS is designed to provide data for product passports, rather than being a passport itself. The distinctions between the PCDS and product passports are scope, complexity and scoring. Passports often have a broader sustainability or functional scope beyond basic circularity criteria, often require greater data complexity in their declarations, and often contain a mechanism for scoring of products. The PCDS supports the functions with data, but is not designed to provide them itself.

2.5. Developing Problem Statements

2.5.1. State of Play Analysis

These key activities were performed between mid-2018 and end of 2019:

- Cluster-based state-of-play analysis of current/past initiatives in order to:

- Identify leading schemes in terms of “potential market penetration” and “emphasis on circularity”. The BAMB initiative had previously conducted a state-of-the-art survey on materials passports-related activities, which served as one starting point [16]. Using that information as well as a literature search and consultations with stakeholders, more than 50 schemes were identified. See Section S1.1.1 of Supplementary Materials S1 for examples of referenced schemes. From those, a smaller group of 13 was selected for further analysis, as a detailed assessment of all product schemes and their data requirements was beyond the scope and resources of the survey. An evaluation of potential market penetration was performed, largely on a qualitative basis, using available knowledge of stakeholders about the market and geographical reach of each scheme. For example, some were geographically limited to individual countries while others were run by multinational companies with a global reach. Evaluation of circularity criteria of those schemes was based on factors including the following: (a) CE criteria gleaned from the BAMB state-of-the-art survey. (b) Results of that study had been incorporated into the previously described materials passport piloted by BAMB. A summary of that experience and other platforms was published [29]. (c) Criteria from the Cradle-to-Cradle Design protocol and certification [47], on which many CE criteria are based, were reviewed, as were formative reports on the Circular Economy published by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF), in which one of the authors of this article participated [48]. Using those as guidance, a graph (unpublished due to potential impacts on competitiveness) was developed showing market penetration potential on one axis and emphasis on circularity on the other. “Emphasis on circularity” refers to the number of CE criteria used in the product scheme. The criteria are (1). Product composition (2). Toxicology of materials (3). Sourcing of materials (4). Product maintenance and reparability (5). Product life extension (6). Product disassembly (7). Product recyclability. A “high” number on that axis denoted that the number of criteria in a scheme was >5. On the regulatory side, ILNAS delivered a standards-watch describing technical committees as well as ISO and CEN standards that could be relevant for Circularity Datasets [49]. This analysis provided insights into the definitions and methods that could affect the PCDS.

- Better understand the current ‘ecosystem’ of initiatives and position the PCDS within that ecosystem. Collecting information allowed identification of sectorial divisions as well as the larger ecosystem. These are described under Results.

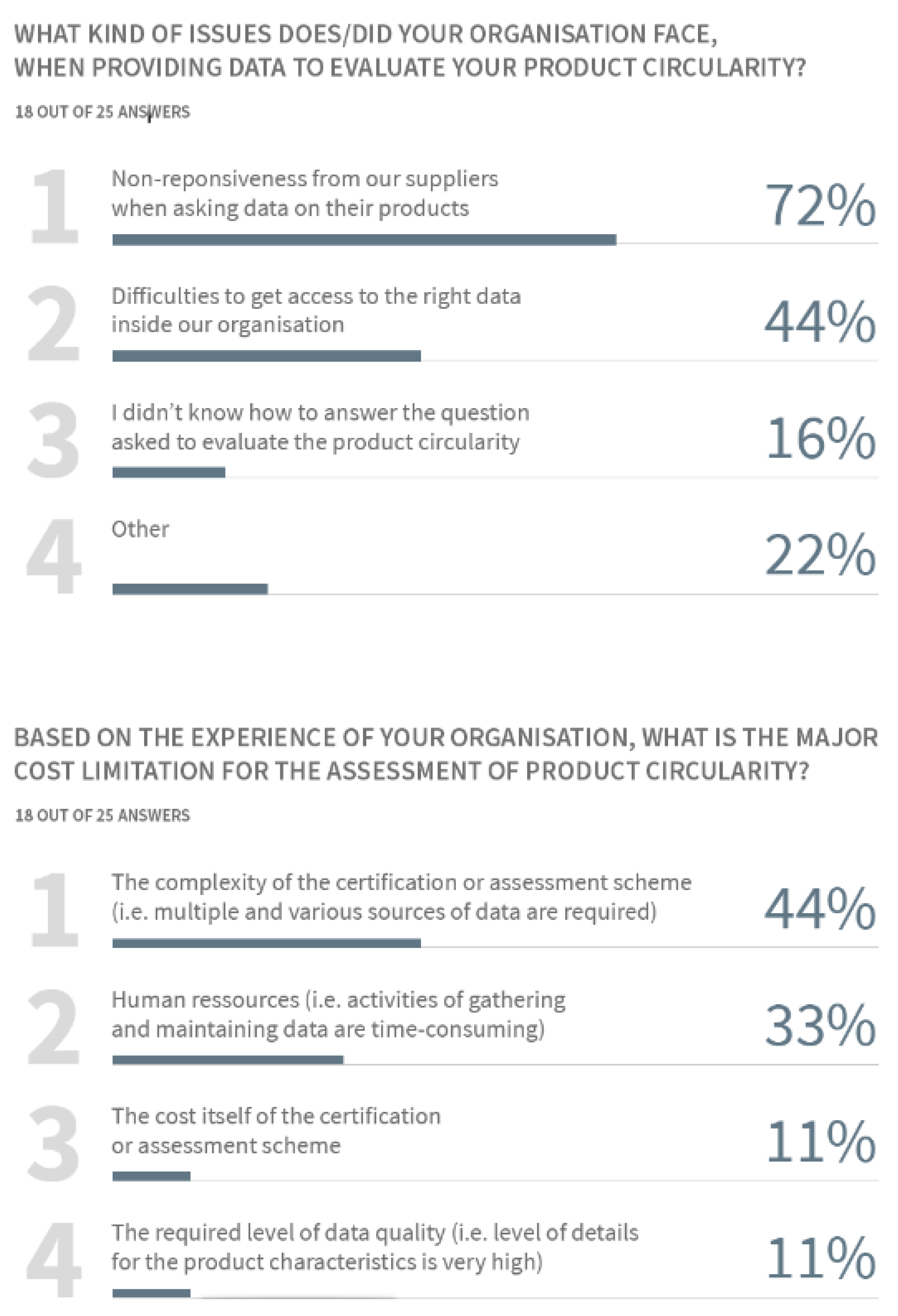

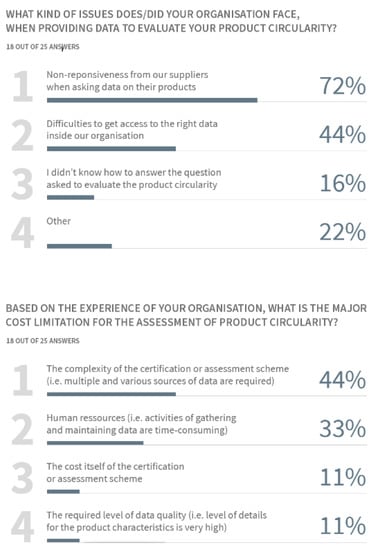

- A survey was conducted in July 2019 within the DWG and SG to understand the needs of manufacturers. This was partially web-based with 25 respondents, and partially workshop-based, as described later under Development of a PCDS Proof of Concept. Figure 1 shows the results.

Figure 1. Participants’ responses to questions on challenges in accessing data to evaluate product circularity.

Figure 1. Participants’ responses to questions on challenges in accessing data to evaluate product circularity.

2.5.2. Solution Development

Development of a PCDS Proof of Concept (POC)

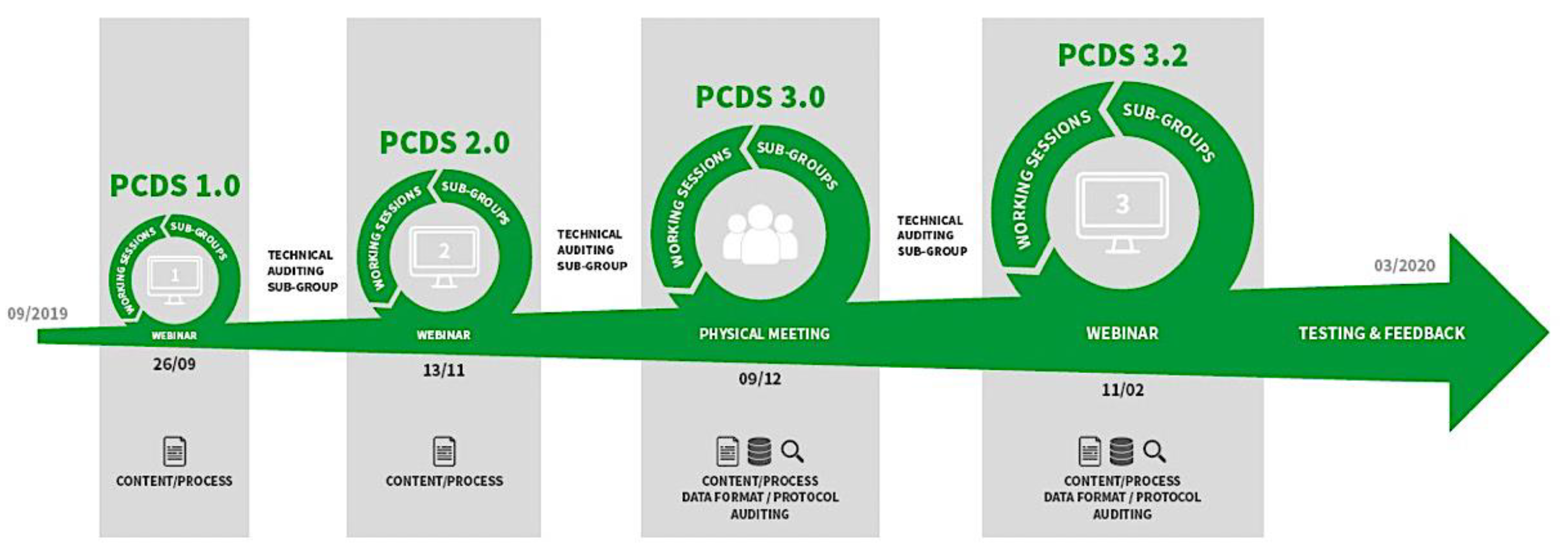

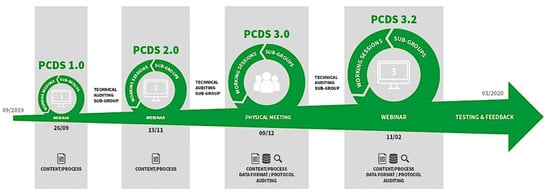

Between mid-2018 and mid-2021, parallel to and following the state-of-play analysis summarized under Results, The Ministry of the Economy organized a proof-of-concept process to develop the basic PCDS template and content, followed by a data format and audit procedure. See Figure 2. This included three webinars, nine subgroup working sessions, and one physical meeting with the DWG, as well as testing with manufacturers and key stakeholders [50].

Figure 2.

Proof of Concept process.

Due to limited resources, it was not possible to canvass many commercial sectors. As a result, the focus was on the built environment, furniture, and fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG). These were selected due to the scope of products within their sector and the growing attention by those sectors to the CE. Additionally, the data aggregation platforms that the PCDS initiative worked with provide services to sectors such as automotive, garments, base chemicals and base materials. This provided added insight into those sectors.

The circular economy is at the early stages of data development, collection and standardization. As a result, the methods used by platforms to select CE criteria, and especially the scope of those criteria, appeared to vary considerably. Some were based on the developers’ own scanning of the literature as well as perceptions of distinctions between the CE and the wider sustainability field. This was also evident from our own scanning of review papers that attempted to summarize the CE from other publications. This was complicated by the previously described absence of widely adopted CE standards. A leading concern was how to determine the scope of PCDS statements? Since the earlier BAMB project struggled with this, there have been continuing discussions over where CE data stops and other green data such as sustainability starts, for example in relation to the UN Sustainable Development Goals [51]. The guidance used to answer this question was; which data for the circular economy, as defined in the nomenclature, are missing or not standardized from other green or sustainability criteria? For this, an examination was conducted of various sustainability mechanisms, as described in Supplementary Materials S1 (See p. 2 item 3. Barriers and opportunities in accessing circularity data). However, it was also noted that the answer to what is circular vs. what is sustainable is open to subjective judgement of users and the demands of the marketplace. Due to all these factors, a main criterion used to determine the suitability of CE criteria for the PCDS was feedback from the main PCDS constituency; intended users themselves. While this was an imperfect process, it resulted in a list of criteria that seemed to address CE data gaps without being excessively wide in scope. Importantly, earlier attempts at broader criteria resulted in negative feedback from users who reported that it was too time-consuming, as observed by some of the authors during the BAMB project.

Testing the PCDS with Manufacturers and Suppliers

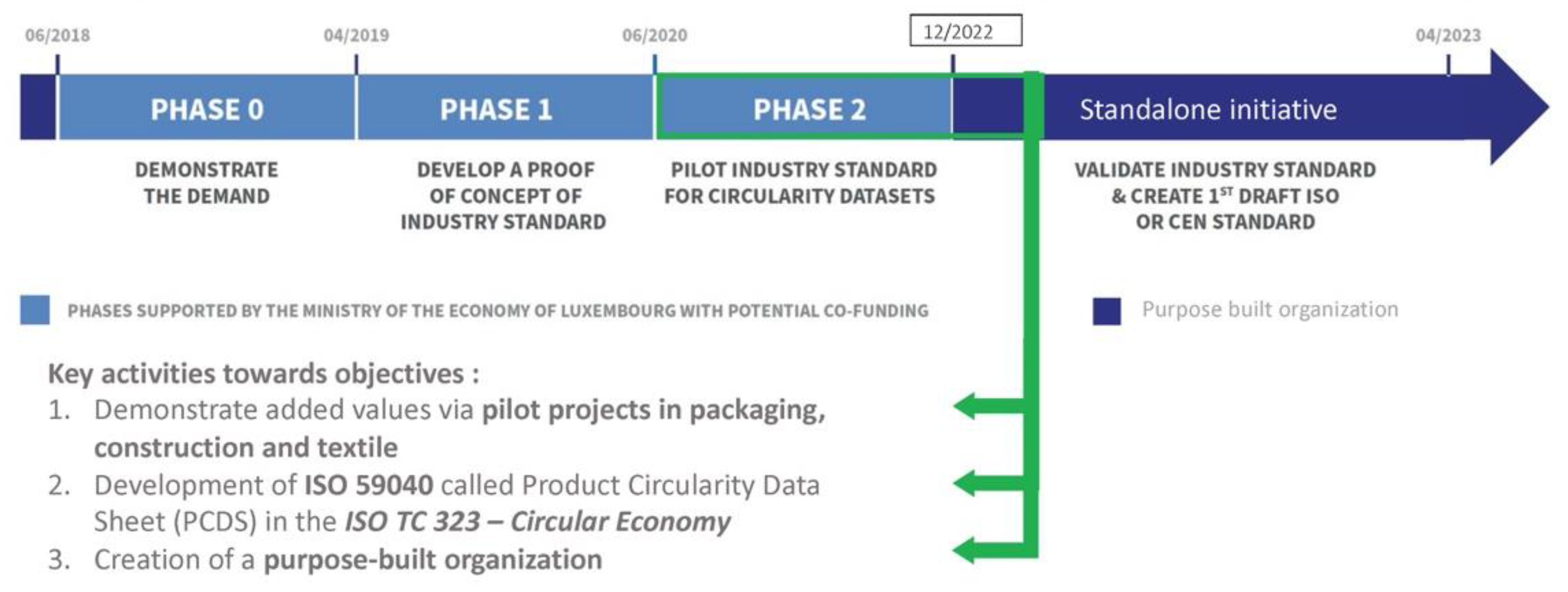

Approximately 50 organizations were consulted, to align the PCDS with them and identify partners for scaling up. Manufacturing organizations active in the construction or Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) sector tested the PCDS and sent feedback. Among those, four manufacturers tested the PCDS, across their supply chains, where each supplier also completed a PCDS. This resulted in a more complete picture of how the PCDS is used. Comments from platforms and methods developers were also collected from, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), Cobuilder, EMF, Ecopreneur, Underwriters Laboratories (UL), the Cradle-to-Cradle Product Innovation Institute (C2CPII), and others. PCDS definitions and statements were the focus [43]. In the case of Cobuilder, there was further collaboration to integrate the PCDS into its platform. For others who were not part of the collaborative process, a consultative call was conducted on PCDS how well the objectives were understood and how the PCDS could be used. Figure 3 provides an overview of the timeline and activities until December 2021.

Figure 3.

Timeline of PCDS initiative.

Information Technology Ecosystem and Business Requirements

Near the end of Phase 2, the Ministry of the Economy commissioned the state agency InCert to develop an IT Ecosystem and Business Requirements proof of concept. A draft was prepared, and three workshops were held with IT governance experts from the Trust Over IP Foundation (ToIP) [52]. This critical phase described how the ecosystem might be structured and operated. Several drafts were developed and analyzed.

2.5.3. ISO Initiative

Beginning in 2019 and parallel to the POC process, the Ministry of the Economy and ILNAS initiated a proposal to the ISO to develop a working group on the PCDS. This proposal was accepted in an ISO vote as ISO/AWI 59040 [34]. Those deliberations are ongoing and are restricted to working group participants, so are not described here.

3. Results

As with the Materials and Methods section, these are divided into Problem Statements and Solution Development.

3.1. Problem Statements Arising from State-of-Play Analysis

For more details on the state-of-play analysis, see Supplementary Materials S1 containing amended excerpts from a report to the Ministry [53].

3.1.1. Circularity Data Marketplace Is Fragmented

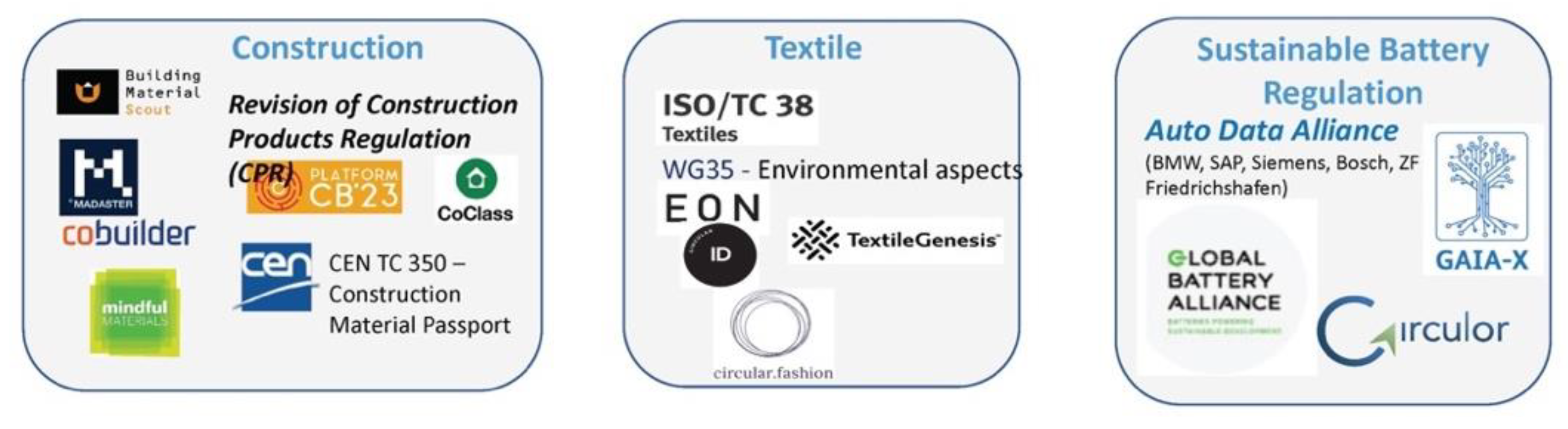

Sustainability and circularity data initiatives are multiplying as illustrated by the examples in Figure 4, which is divided into standardization, EU regulation and platforms. A similar set of initiatives is divided by sector as illustrated in Figure 5. These figures are exemplary only. The full list of initiatives is described in an unpublished annex to the state-of-play analysis excerpted in Supplementary Materials S1.

Figure 4.

Categories of diverse and expanding numbers of initiatives. The three most active sectors in CE product-related data management: construction, textiles, and batteries. Siloing of initiatives into these three industry sectors is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Sectoral and intra-sectoral fragmentation.

There is currently no widely accepted initiative, due to platform proliferation, lack of shared definitions for circularity, and lack of unified policies on circularity data. These are detailed further in Supplementary Materials S1. Most initiatives are still relatively new, and it is unclear which ones will develop over time. However, the sectoral fragmentation points to a fundamental problem with current schemes and proposals for future schemes. Siloing in sectors risks creating a barrier to materials traceability and data management across sectors. Many products, such as pumps and electronic circuit boards, are used in multiple sectors. If each sector has its own method of organizing the data, cross-sector data exchange for e.g., recyclers risks becoming dysfunctional. This is explored further under Section 4.

3.1.2. Circularity Data Schemes Are Complicated by Perception of Cost and Technical Complexity

- In the building and packaging sectors, companies often react to demands for greater transparency, focusing on waste management and climate impacts as cost centers, rather than developing CE value propositions as revenue and savings centers. As a result, many still do not see the business case in collecting and disseminating circularity data. This is despite many case examples of economically successful circularity initiatives being published in recent years.

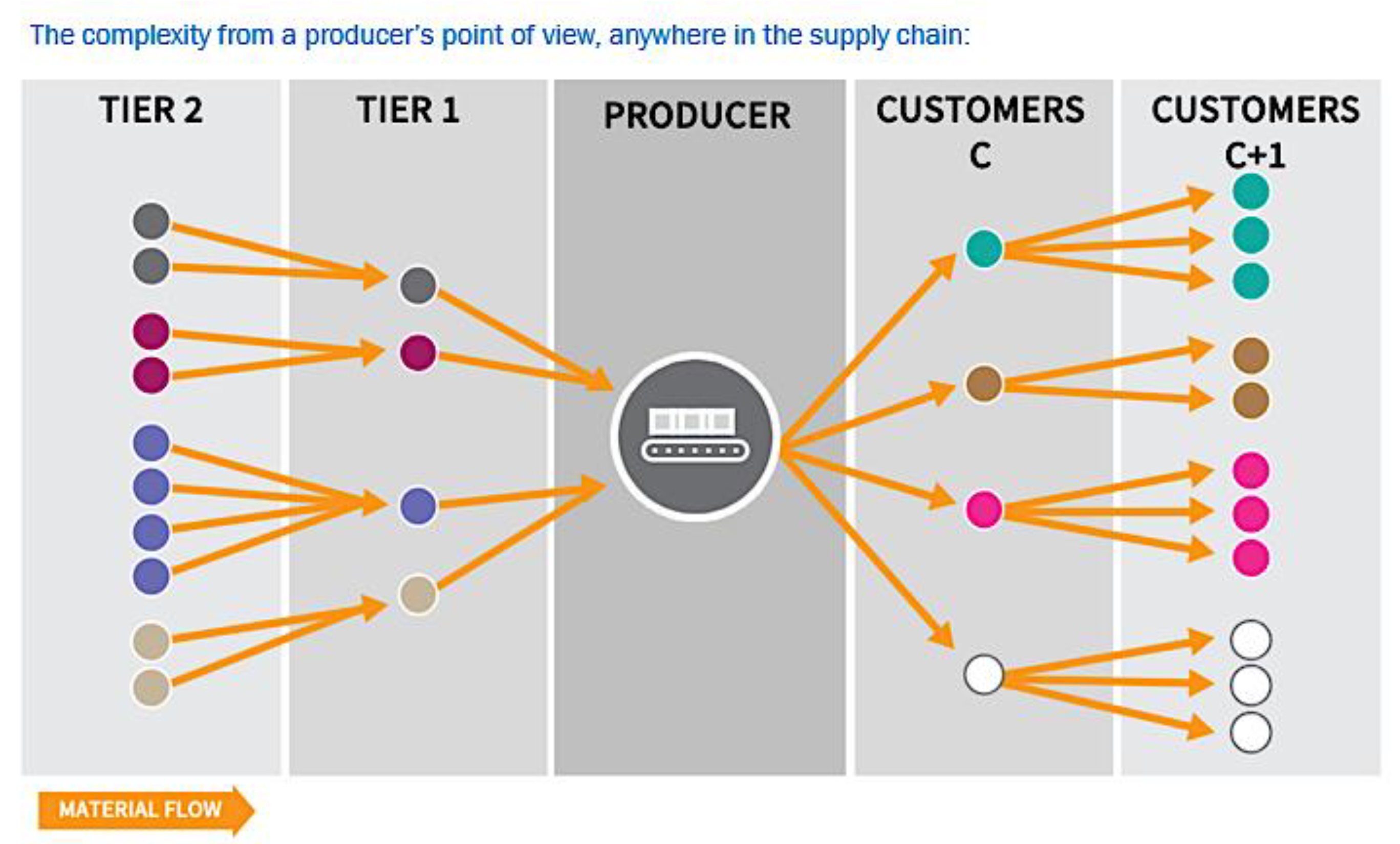

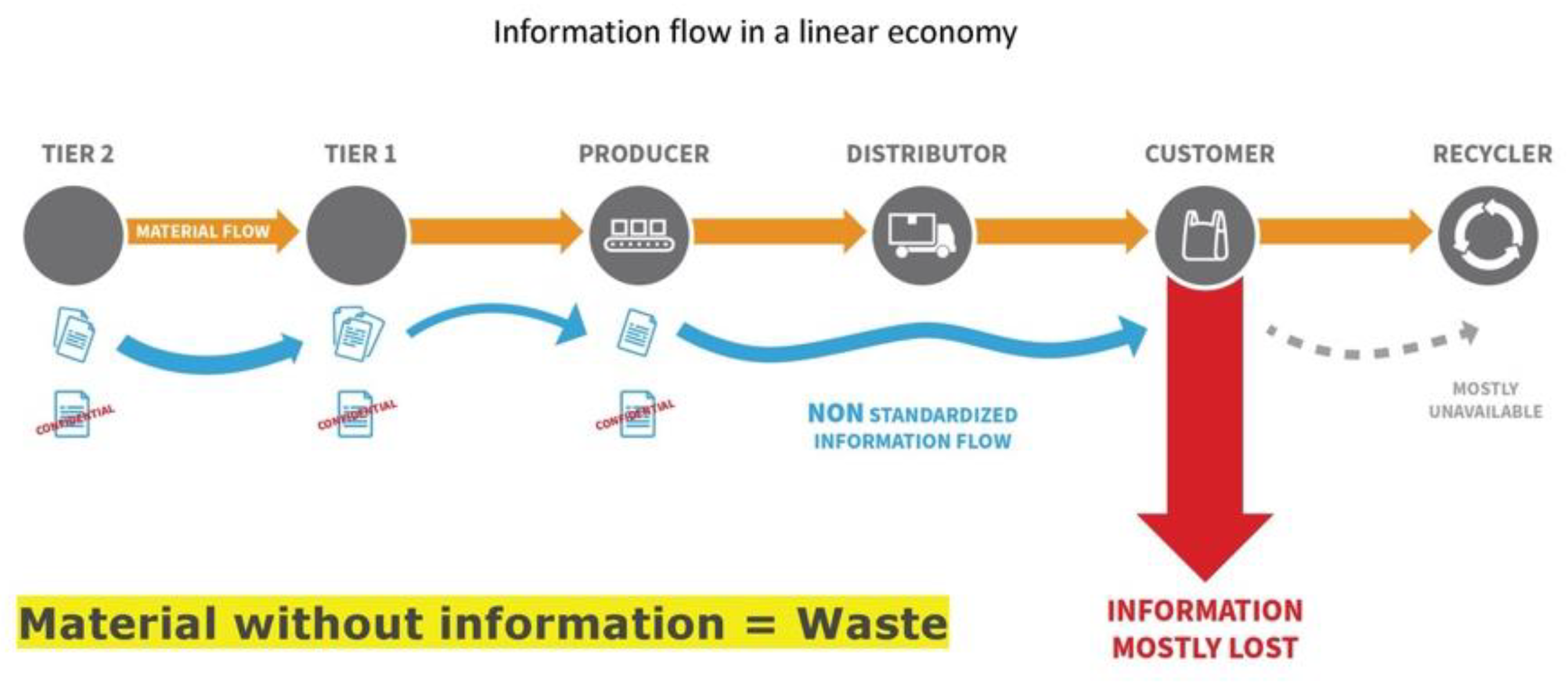

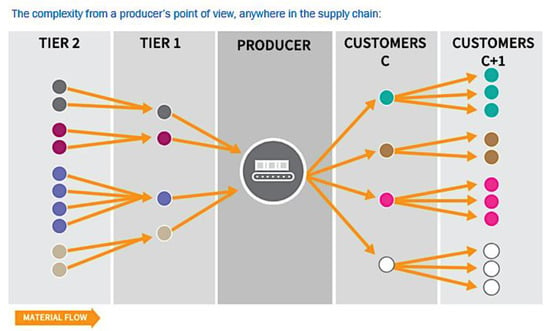

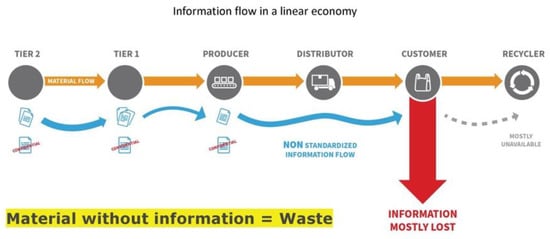

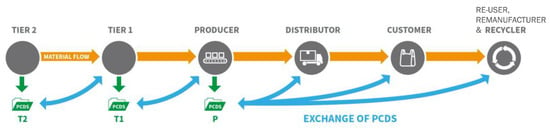

- Product information needs to differ among actors in the supply and use value chain per Figure 6. Additionally, Figure 7 shows how data for circular evaluation are lost in the current linear economy. Contributing factors, described in more detail in Supplementary Materials S1, include: Absence of shared or open standardized formats, reluctance by manufacturers to disclose trade secrets, unverifiable data or sources, and changes to circularity characteristics when one product is integrated into a larger assembly. Most solutions still start with the final product in a supply chain. Detailed transparent information for each supplier component remains difficult to distinguish, and suppliers are forced to provide the same data in different formats.

Figure 6. The complexity of communicating circularity data along the supply and use chain, from the product producer (manufacturer/assembler) point of view.

Figure 6. The complexity of communicating circularity data along the supply and use chain, from the product producer (manufacturer/assembler) point of view. Figure 7. Loss of non-standardized information.

Figure 7. Loss of non-standardized information.

3.2. Solution Development

The following section summarizes parts of the earlier referenced report published by the Ministry of the Economy [54]. See Supplementary Materials S1 and S2 for details.

3.2.1. Product Circularity Data Sheet (PCDS)

In order to address barriers and opportunities identified during the consultation process, the PCDS was co-created between the Ministry of the Economy, PositiveImpaKT, and more than 50 manufacturers, data aggregation platforms and standards bodies. According to the report to the Ministry,

“To enable efficient and secure exchange of product circularity information along the value chain, standardization of the data and format is needed, including an auditing process” [54].

Overview of the PCDS Model

Objectives and design principles are quoted or paraphrased from a report to the Ministry [54]. See also Supplementary Materials S1 for details.

Objectives

- Provide basic circularity data on individual products.

- Improve circularity data sharing efficiency.

- Encourage improved product circularity performance.

Design Principles

- Provide standardized information for others to do circularity evaluations. The PCDS is not a ranking tool itself.

- Provide information according to “how the manufacturer designed the product to be used, not on how the next user in the value chain intends to use it.” For a description of the reasoning behind this important aspect, see Supplementary Materials S1, p. 3. Limit predictions of subsequent usage.

- Provide statements that can be answered as true or false without disclosing trade secrets. This is designed to help resolve a conflict between confidentiality and the need for transparency. The statements describe a set of features that can be transparently stated as true or false without having to disclose to every party the manufacturer’s trade secrets. This statement format also limits errors and enables an automated process to complete the PCDS.

- Does not rely on one centralized database to complete or store completed PCDSs. In this way, manufacturers that create a PCDS keep control over their data and are responsible for updating it. This was a specific need expressed by DWG and SG companies.

- Designed with open-source data protocols for use across supply chains and networks.

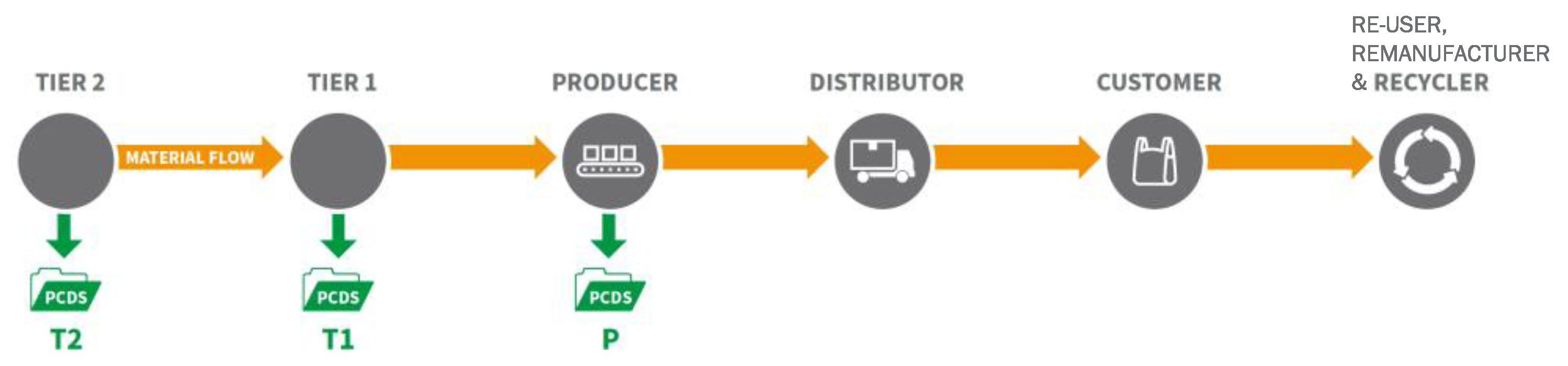

Who Is Authorized to Create a PCDS

A PCDS is created and modified by a manufacturer. The manufacturer can be a supplier of components (tiers 1 and 2) or an assembler of the final product (producer). See Figure 8. If product composition is modified as with chemical combinations, or if new information becomes available on regulations or circular characteristics, these trigger PCDS modifications. In the case of repair or remanufacturing, a PCDS can be modified or a new PCDS issued. This depends on the extent of work and who performs it.

Figure 8.

Who can create a PCDS. In this diagram, “Producer” is a manufacturer. Remanufacturers can also create a PCDS (example not shown).

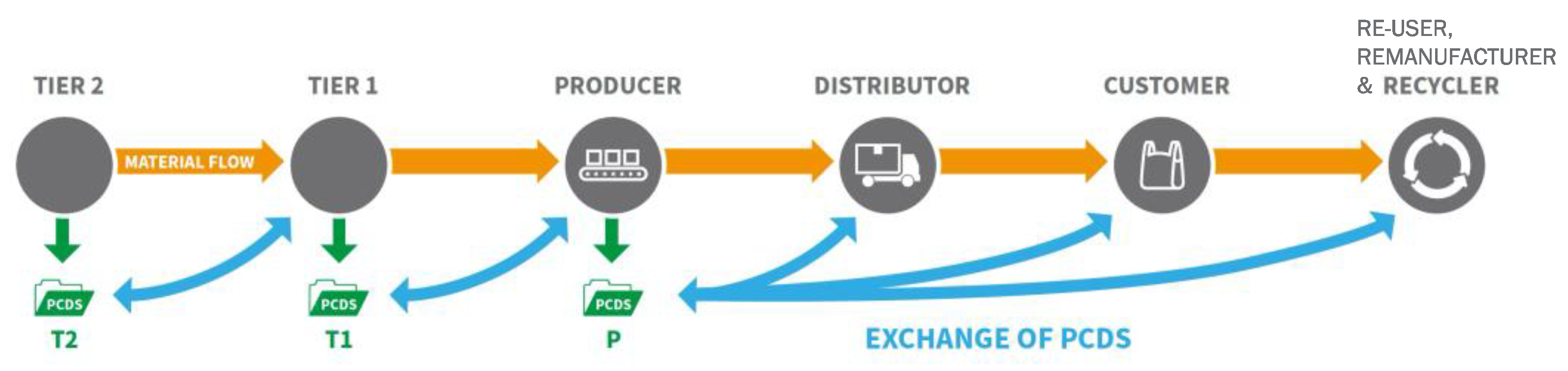

PCDS Users

The main users are stakeholders participating in circular business models. See Figure 9.

Figure 9.

PCDS users. In this diagram, “Producer” is a manufacturer. A remanufacturer uses the data from a PCDS, and can also be considered a manufacturer who generates a new PCDS after remanufacturing is completed.

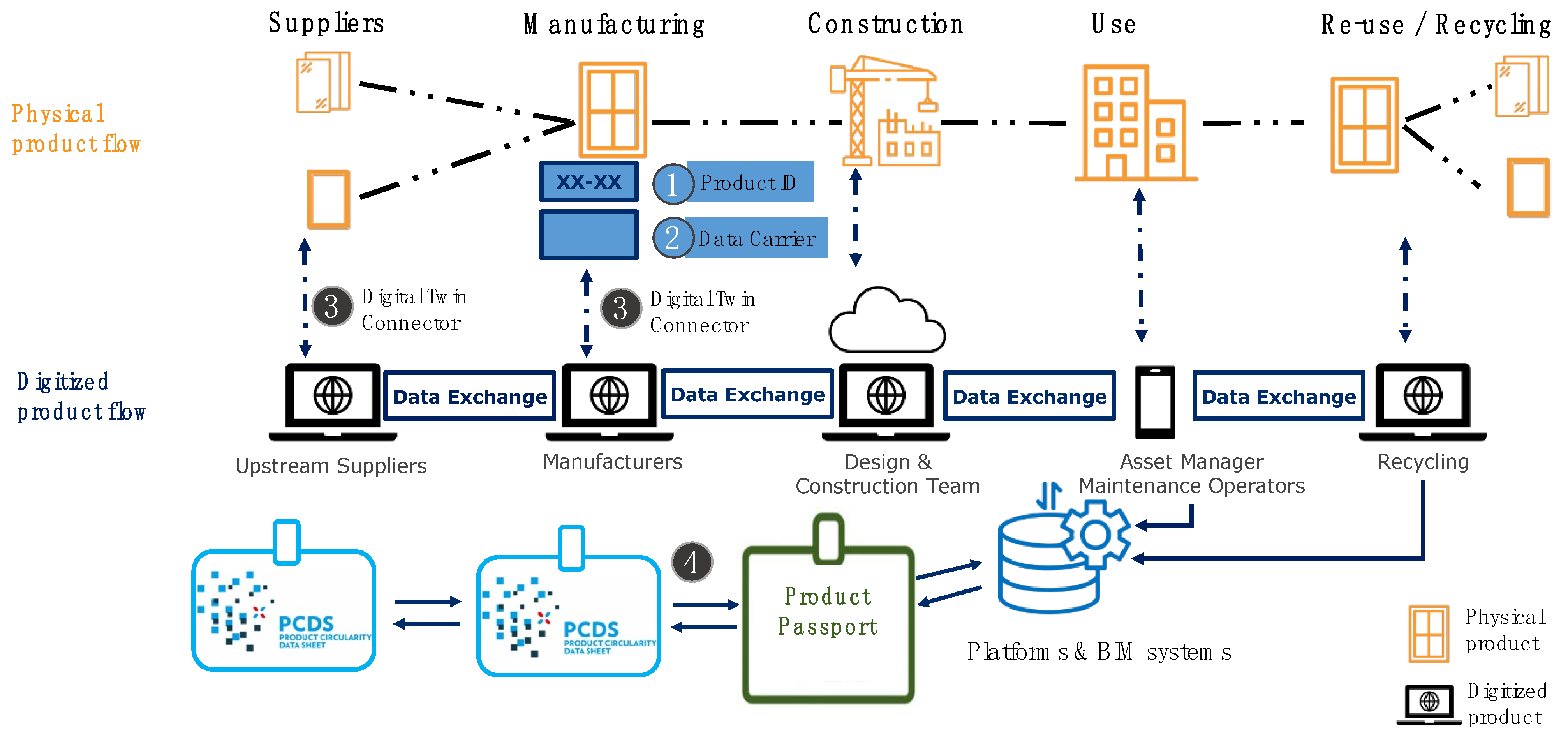

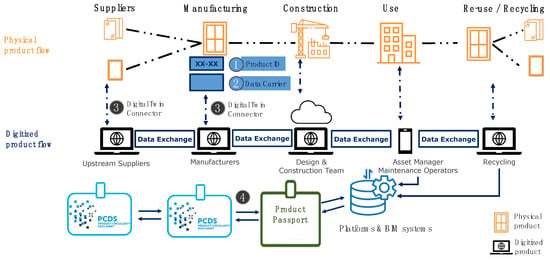

The PCDS is also designed to support digital product passport (DPP) systems being propelled by various agencies and platforms as described in the introduction. Using the example of a window, Figure 10 shows how the PCDS supports circularity data flow in the construction sector.

Figure 10.

Where the PCDS fits into the product passport ecosystem, using the example of a window.

3.2.2. Conceptual Technical Model

The PCDS technical model is based on an open-source system concept comprised of these components, and organized around the product level (see nomenclature for definition of product):

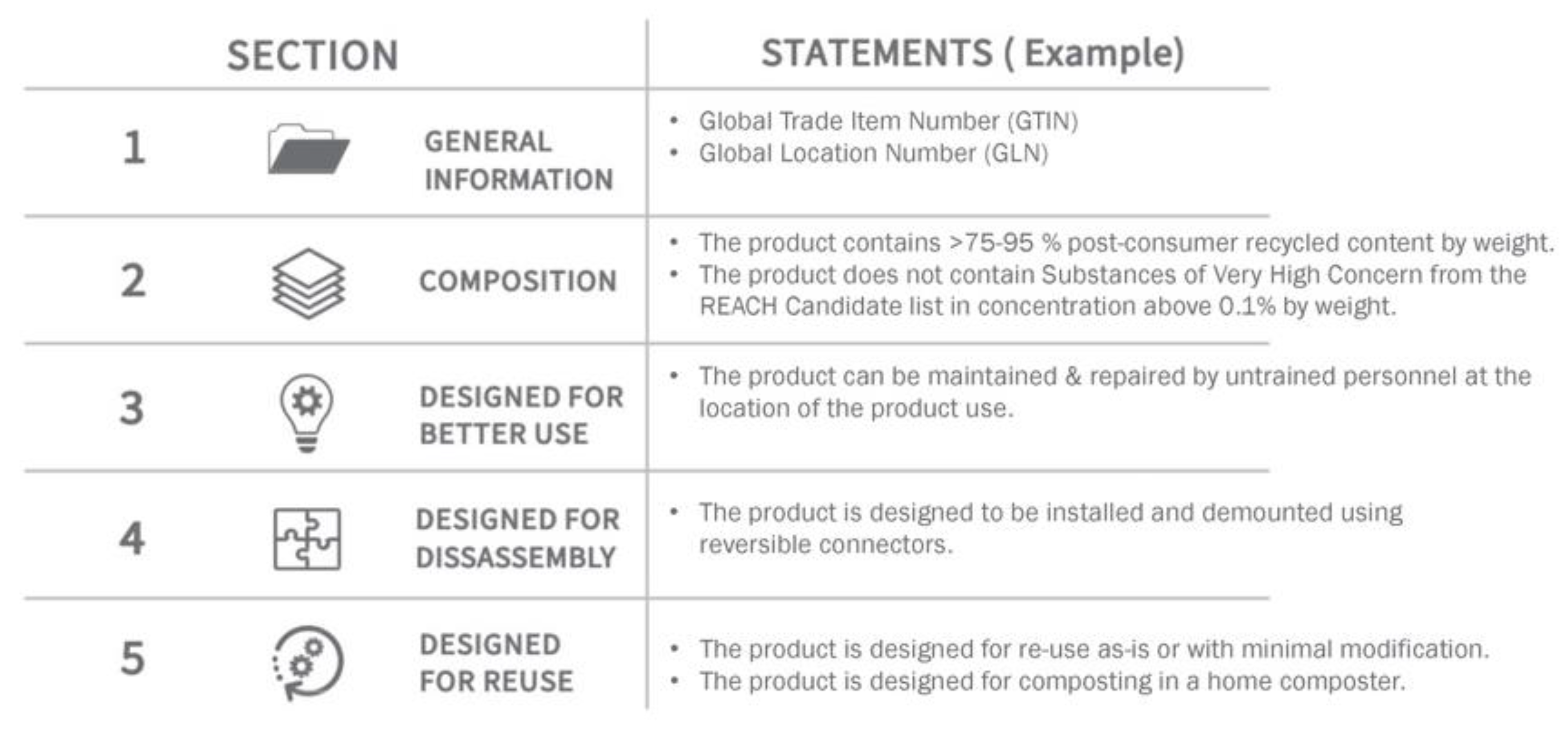

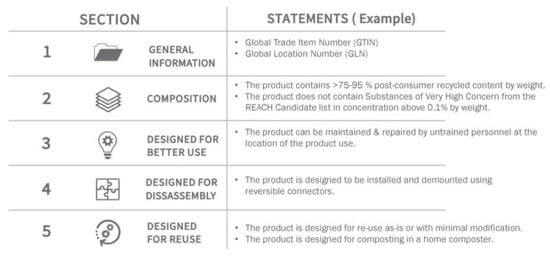

- (1)

- Data template containing standardized, trustworthy statements about product circularity in a true/false format. The template is organized in five major sections. See Figure 11. The template is designed to be completed as a fillable PDF. It is also translatable into a machine-readable format such as XML or JSON. The PCDS modular structure allows import into and export from databases. The whole blank or completed PCDS template can be imported into the database of a manufacturer or data aggregator, or the individual blank or completed statements can be imported, allowing a PCDS to be generated from that database. The original completed PCDS resides on the website of the manufacturer and is available for download by any individual who has access to that site. It can also be integrated into an IT ecosystem where multiple PCDSs from suppliers are assembled into a PCDS for a final assembled product. See Supplementary Materials S2 for the detailed template.

Figure 11. Sections of the PCDS template.

Figure 11. Sections of the PCDS template. - (2)

- Guidance for completing a PCDS, to provide references to standards norms, and definitions. This guidance is attached to the PCDS template, and provided separately for database users to refer to. See Supplementary Materials S2 for detailed guidance.

- (3)

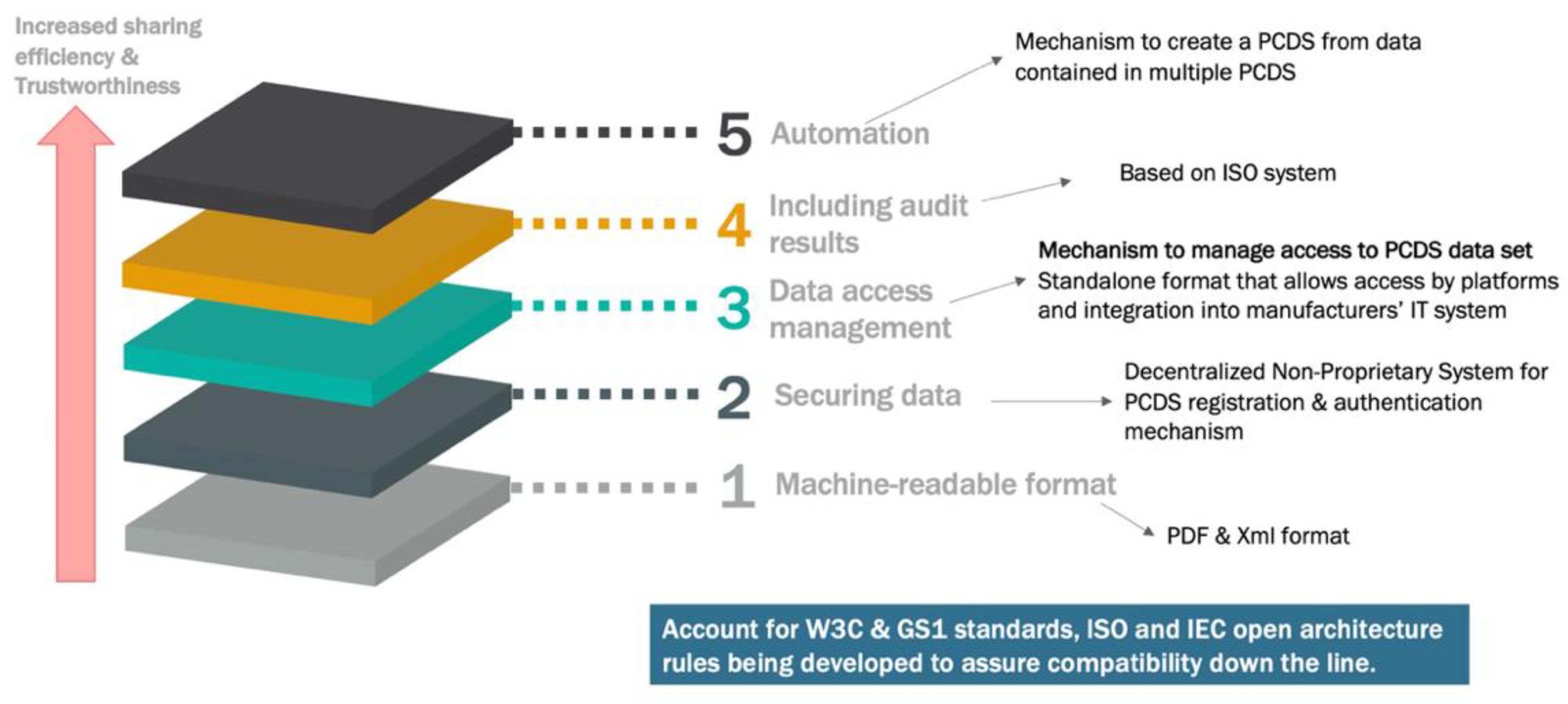

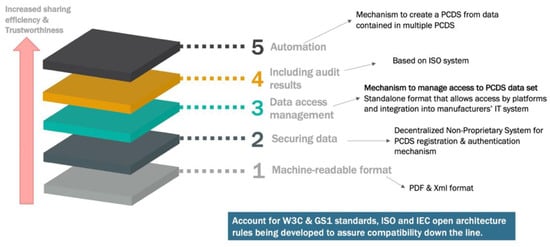

- IT Ecosystem Concept. As part of the previously described BAMB project, a concept for an IT infrastructure for passports was presented [55]. It became clear during the PCDS process that an IT ecosystem infrastructure is also required in order to issue unique IDs and facilitate assembly and trustworthy exchange of PCDS data. A draft outline of that infrastructure is being developed by InCert under supervision of the Ministry, and with input from PositiveImpaKT. In their present draft forms, the components of the IT ecosystem are each in various stages of development and include:

- Standardized PDF template supported by a machine-readable XML format for storing data, as described under (1) previously. These have been developed.

- Standardized protocols for securely exchanging the PCDS. This includes a decentralized system for PCDS registration and authentication. These are being developed and are not a topic for this article.

- Standalone format to avoid reliance on central databases. The PCDS can stand on its own on a manufacturer’s website without any central database or ecosystem to create it. Additionally, there is no central database containing all PCDSs and their data. However, depending on the evolving technical capacities of distributed systems, a global node could be established to allocate unique IDs and hold the master PCDS template for downloading. The standalone PCDS has been developed. The global node is still being considered.

- Audit reporting built into the data template. The audit procedure is in development and is not a topic for this article.

Automation to integrate data from multiple input PCDS. Includes protocols to support Application Program Interface (API), and protocol to inform stakeholders when a PCDS revision is made. The automation to integrate data from multiple PCDS is ready to pilot. The remainder of the system is under development.

See Figure 12 for graphic representation of these 5 aspects.

Figure 12.

Functional components of the PCDS ecosystem to assure trustworthiness.

3.2.3. Business Model

The PCDS must serve the business requirements of its users. Testing PCDS business models is still in its infancy, as an operational IT ecosystem is required for validation. Based on feedback from stakeholders, the business model should account for these needs:

- Standardized method to obtain data from suppliers, to save time and costs. This is being partially addressed through an assembly function that lets manufacturers automatically fill out a PCDS for an assembled product based on multiple PCDSs provided by component suppliers. The function avoids having to manually answer certain statements if these are confirmed by totaling the results of component PCDS statements. As described in the introduction, MSMEs often lack resources to provide data, thus an assembly function combined with an interoperable format is key, as most manufacturers are MSMEs. This is still in development.

- Recognition of the PCDS in sustainable building certifications and procurement tenders.

- Capability to integrate the PCDS into data aggregation platforms. Piloting is underway for the built environment with the previously described organizations Cobuilder, Madaster, and EPEA. Piloting with a wider range of materials is underway with Toxnot.

- Completing the ISO PCDS process, which will result in the PCDS becoming a global standard. This will accelerate and ease the exchange of PCDS data.

- Continuing to align with the EU Digital Product Passport initiative.

As it is too early to determine which of these will be attractive to users, there is no further discussion of the business model in this article.

3.2.4. Embodied Carbon and Energy as a PCDS Content Issue

The question of embodied carbon and energy as well as energy use was addressed during PCDS development and testing. At the time of writing, the situation was as follows:

- (1)

- This early version of the PCDS is intended to fill gaps that other norms do not yet fill. Embodied carbon and energy are among the most extensively covered parameters by other norms such as ISO 14067:2018 and Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs).

- (2)

- Parameters that have significant impacts on embodied carbon and energy for present and future use are included in the PCDS. The Guidance to statement 2.1 Positive Impacts, includes “activities that generate carbon offsets (and) measuring outputs of renewable energy.” Recycled content, as well as reusable, repairable and recyclable features are also major sections in the PCDS (See Supplementary Materials S2).

- (3)

- Embodied energy and carbon as reported through other norms are being considered for later versions of the PCDS. A strong impetus to include these was not encountered from manufacturers and other groups who participated in the consultations, as it was seen that they were already reporting on these under other norms. At all costs, they wanted to avoid having to provide different carbon and energy calculations than other norms already require.

The inclusion of carbon and energy related items is still under active consideration at the time of writing.

3.2.5. Novelty

There is no globally accepted, open source, standardized mechanism for describing the CE characteristics of products. The PCDS model resulting from the previously described process consists of a novel combination of features that gives it the potential to be such a mechanism. Individual features are not novel, but the combination seems rare.

- Except for product identifiers, it does not require the freeform text inputs mandated by sustainability and safety declarations such as the earlier-referenced SDS. Instead, the true/false format allows for easy completion and automated assembly of multiple PCDS issued by suppliers as their products move along the supply cycle and become components of other products.

- There is no centralized database where all PCDSs and data feeding them are stored. The PCDS structure allows a top-down or bottom-up approach, where data can be requested from suppliers by Original Equipment Manufacturers, then assembled, or the suppliers can generate their own PCDS and provide those to the market.

- The PCDS is accessible by anybody and is open source.

- The PCDS aims to be applicable to every product sector, as compared to materials and building passports from the building sector, and mechanisms from other sectoral initiatives such as batteries. There has been controversy over whether this is practical in the context of diverse sectorial initiatives. This is currently under discussion.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

The PCDS has only been tested with a few sectors, including construction, textiles and some FMCGs. Experience with other sectors will certainly result in modifications. Few MSMEs have tested the PCDS yet. Although this article benefited from extensive analysis of passport initiatives conducted by other reports, due to economic constraints the authors did not conduct an exhaustive statistical analysis of each of the hundreds of published research papers regarding product and material passports. The IT ecosystem still has to be developed in order to complete testing of the model. Once the ecosystem and audit procedures are finalized, these could affect the structure and implementation of the model. Taken together, these limitations confirm that the PCDS is at a beginning not an end. Comparison with other initiatives. As described previously, the vast majority of initiatives are wider in scope or different in scope than the PCDS. The BAMB project spent years and large sums on comparative analysis, then concluded that something such as the PCDS was required. Some of the reviews cited in this article attempted to compare aspects of various sustainability standardization approaches. However, due to space limitations, it is beyond the scope of this article to analyze how other dataset initiatives such as passports deal with similar opportunities and problems such as authentication, business case cost/benefit, CE criteria definition, standardization, and governance. Experience with the PCDS to date represents a contribution to solving those challenges, but an in-depth assessment will be more feasible after the PCDS ecosystem is further developed and tested.

4.2. Were the Objectives Met?

The result for objective 1. is a PCDS template to provide a standardized true/false statement format for sharing basic circular information about products. This was tested with stakeholders. (See Supplementary Materials S2). However, there are still challenges to balance demands from diverse sectors, with the limited capacities of MSME 1st and 2nd tier suppliers to respond. On one hand, flexibility in the PCDS is required to account for the distinctions between e.g., sheet metal that goes into hundreds of products, and a computer using that metal, or cellulose products that go into hundreds of products, from tissue paper to books. On the other hand, suppliers at the beginning of the cycle who sell into hundreds of markets and sectors are often unaware of who ultimately uses their products because they are sold through intermediaries. MSMEs often lack the resources to provide different iterations of CE datasets to different sectors. Because of this, the biggest risk facing the PCDS is fragmentation through multiple sectorial versions. This can already be seen in the different types of product passports being developed, as described under Problem Statements. Part of this is being addressed through the previously described assembly function that allows one PCDS to feed into another along the cycle. The further use of AI-assisted algorithms could also provide solutions. For the other two objectives, it is too early in the process to tell, since the PCDS IT ecosystem is still being established.

4.3. Policies

A policy objective of introducing the PCDS to the ISO was met and the working group process is underway. As the deliberations are restricted, it is not possible to comment on those. The PCDS process to date suggests that any regulation or policy mandating this type of data gathering and dissemination needs to be conducted in stages, starting with something that is practical and basic, but at the same time guarding against being simplistic in order to avoid the risk of misrepresenting circular characteristics. The capacity constraints of MSMEs particularly need to be considered. Certainly, software can play a significant role in simplifying the data gathering task. This requires further investigation as to how policies could support the needs of MSMEs.

4.4. Future Research Directions

The PCDS will evolve as CE performance criteria become clearer in the marketplace. The PCDS needs to be tested with more MSMEs to validate whether it is a user-friendly support system that saves time and costs for them. To do this, it is necessary to demonstrate its value by: conducting more pilots, defining governance, establishing auditing procedures, and testing business models. While the PCDS template is designed to be a simple tool for users to apply, the ecosystem backbone and governance that surround it involve a greater level of complexity to allow many users to apply the template in a low-cost, globalized, and standardized setting. The governance and IT ecosystem, including connections to other ecosystems and alignment with many other standards, are part of this complexity. To address this, the following future research directions were identified.

- Continuously evaluate the scope and content of PCDS statements so they align with global and sectorial requirements. This will be conducted partially through the ISO, possibly the DPP, and in collaboration with sectorial passport initiatives. Among the items to be considered is embedded carbon.

- Maintain a user-friendly interface that allows especially MSMEs to use the system at very low cost, regardless of the complexity of the ecosystem backbone.

- Describe a mechanism for governance bodies to collaborate at the global level to maintain a global standard. This includes the ISO and any regional bodies that might emerge.

- Optimize the authentication mechanism for PCDS issuers and the validity of the PCDS itself. As hacking attacks become commonplace, assuring the trustworthiness and business viability of the system is paramount. Identifying state-of-the-art solutions with e.g., advanced decentralized systems is a priority. This is not limited to the PCDS.

- Connect the PCDS more strongly with business cases. More pilot projects are required to test added value.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en15093397/s1, Supplementary Materials S1. Amended excerpts from Ministry of the Economy of Luxembourg Final report. Luxembourg Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative. 2020. Supplementary Materials S2. PCDS form and Guidance created 2020 for piloting [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, D.M. and T.W. Writing—review and editing, all authors. Illustrations were conceptualized by the authors except where noted under acknowledgements. Funding acquisition, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Ministry of the Economy of Luxembourg. “Circularity Datasets standardization—Phase 2”, Call for proposals: Project management to position and strengthen the product circularity dataset (PCDS) including its auditable industry standard 27 August 2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No animal or human subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

No human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data is in Supplementary Materials S1 & S2.

Acknowledgments

The following contributions are gratefully acknowledged. Christian Tock and Jérôme Petry from the Ministry of the Economy of Luxembourg for leading the PCDS initiative on behalf of the Ministry, and co-creating and reviewing the PCDS, and to Jérôme Petry for leading the ISO initiative, and for his editorial input to this article. The editorial contributions of Ian Stewart, University of King’s College, Halifax, Canada and Werner Lang, Department of Architecture, TU Munich.

Conflicts of Interest

Jeannot Schroeder and Anne-Christine Ayed are principals in the consultancy PositiveImpaKT. The authors received salaries or other funding from PositiveImpaKT, which received funding from the Ministry of the Economy of Luxembourg to support establishing a PCDS. The authors are external to the Ministry. Representatives of the Ministry were involved in co-creating and reviewing the state-of-play analysis, and in organizing and conducting workshops.

Nomenclature

See Supplementary Materials S1 and S2 for further terms. CE Criteria. Criteria that support and fall within the definition of the circular economy as described here. In this article, the criteria are defined at a product level. Circular economy (CE). An economy that is restorative and regenerative by design and which aims to keep products, components and materials at their highest utility and value at all times, distinguishing between technical and biological cycles [73]. Circular economy value includes material health to account for the following factors: (1) materials that are non-toxic in used amounts and defined scenarios have a higher potential for cycling without contaminating future products (2) direct and indirect impacts on human health and the environment. There are published methods to measure material health [74]. Circularity. A process or characteristic designed to support the circular economy. Demountable. Removeable from a mounting or setting, without damaging the product or its performance (e.g., static and mechanical functions) or contaminating other products or assemblies. For example, a product being demounted from a building or vehicle. (See Supplementary Materials S2 under Guidance “demountable”). Material. A solid, gas or liquid that is homogenous or heterogenous. For the purposes of this paper, material is mainly referred to for composition and safety in a product. Product. A physical-based object designed or utilized with a purpose. A product can be, for example: goods of any type; hardware (e.g., engine mechanical part, spare parts, consumables, etc.); processed materials (e.g., lubricant); assembly of many components. Could range from a metal ingot to an air conditioning unit or shampoo. One product will often be an input, ingredient or component for another. The PCDS is designed to accommodate this.

References

- Liu, Q.; Trevisan, A.H.; Yang, M.; Mascarenhas, J. A framework of digital technologies for the circular economy: Digital functions and mechanisms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Tang, S.; Xia, J.; Lv, Z. Deep learning for assessment of environmental satisfaction using BIM big data in energy efficient building digital twins. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 50, 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbini, A.; Malacarne, G.; Massari, G.; Monizza, G.P.; Matt, D.T. BIM objects library for information exchange in public works: The use of proprietary and open formats. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2019, 192, 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, T.M.; Brajkovich, N.; Minunno, R.; Chong, H.-Y.; Morrison, G.M. Circular Economy and Virtual Reality in Advanced BIM-Based Prefabricated Construction. Energies 2021, 14, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, J.; van Ast, L. Financing Circularity: Demystifying Finance for Circular Economies; UNEP Finance Initiative: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvellec, H.; Böhm, S.; Stowell, A.; Valenzuela, F. Introduction to the Special Issue on the Contested Realities of the Circular Economy; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; Volume 26, pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Framework for Setting Ecodesign Requirements for Sustainable Products and Repealing Directive 2009/125/EC; 2022/0095 (COD); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/system/files/2022-03/COM_2022_142_1_EN_ACT_part1_v6.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Adisorn, T.; Tholen, L.; Götz, T. Towards a digital product passport fit for contributing to a circular economy. Energies 2021, 14, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.; Braungart, M.; Mulhall, D. Resource Re-Pletion. Role of Buildings. Introducing Nutrient Certificates AKA Materials Passports As a Counterpart to Emissions Trading Schemes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.; Braungart, M.; Mulhall, D. Materials Banking and Resource Repletion, Role of Buildings, and Materials Passports. In Sustainable Built Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 677–702. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M.; Lang, W. Materials Passports-Best Practice; Technische Universität München, Fakultät für Architektur: Munich, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-941370-96-8. Available online: https://www.bamb2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BAMB_MaterialsPassports_BestPractice.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Donetskaya, J.V.; Gatchin, Y.A. Development of Requirements for The Content of a Digital Passport and Design Solutions. In Proceedings of Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; p. 012102. [Google Scholar]

- Buildings as Materials Banks BAMB. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1742-6596/1828/1/012102/meta (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Buildings as Materials Banks (BAMB) Library. Available online: https://www.bamb2020.eu/library/ (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Debacker, W.; Manshoven, S.; Denis, F. D1 Synthesis of the State-of-the-Art: Key Barriers and Opportunities for Materials Passports and Reversible Building Design in the Current System. 2016, p. 56. Available online: https://www.bamb2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/D1_Synthesis-report-on-State-of-the-art_20161129_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Benachio, G.L.F.; Freitas, M.D.C.D.; Tavares, S.F. Circular economy in the construction industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nema, D.; Suryavanshi, P.; Verma, T.L. A Study On Ever-Changing Definition of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). 2021. Available online: https://www.recentscientific.com/study-ever-changing-definition-micro-small-and-medium-enterprises-msmes (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Mishra, R.; Singh, R.K.; Govindan, K. Barriers to the adoption of circular economy practices by SMEs: Instrument development, measurement and validation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 351, 131389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alì, G.S.; Yu, R. Artificial Intelligence between Transparency and Secrecy: From the EC Whitepaper to the AIA and Beyond. Eur. J. Law Technol. 2021, 13, 12. [Google Scholar]

- REF-8 Project Report on Enforcement of CLP, REACH and BPR Duties Related to Substances, Mixtures and Articles Sold Online; European Chemicals Agency: Helsinki, Finland, 2021. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/17088/project_report_ref-8_en.pdf/ccf2c453-da0e-c185-908e-3a0343b25802?t=1638885422475 (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Kolchinski, A.G. When Safety Data Sheets are a Safety Hazard. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAMB Materials Passports. Available online: https://www.bamb2020.eu/topics/materials-passports/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- EPEA Benelux-Part of Drees & Sommer. Available online: https://epea.com/nl/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- EPEA Services. Available online: https://epea.com/nl/en/services (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Luscuere, L.; Zanatta, R.; Mulhall, D.; Boström, J.; Elfström, L. Deliverable 7—Operational Materials Passports; BAMB: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; p. 25. Available online: https://www.bamb2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/D7-Operational-materials-passports.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Product Circularity Data Sheet PCDS. Available online: www.pcds.lu (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Paul Schosseler, C.T. Paul Rasqué Circular Economy Strategy Luxembourg; Ministère de l’Énergie et de l’Aménagement du territoire Département de l’énergie: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Luscuere, L.; Zanatta, R.; Mulhall, D.; Boström, J.; Elfström, L. Deliverable 7—Operational Materials Passports; BAMB: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; p. 34. Available online: https://www.bamb2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/D7-Operational-materials-passports.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- PositiveImpaKT. Available online: www.positiveimpakt.eu (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- ILNAS. Available online: https://ilnas.gouvernement.lu (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Luxembourg Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative, Creating a Digital Circularity Fingerprint for Products PHASE 1—FINAL REPORT; Ministry of the Economy: Luxembourg, 2020; p. 14. Available online: https://pcds.lu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/MECO_CEDataSet_PCDS_Public-27072020.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- EPEA. Available online: https://epea.com/en (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- ISO/AWI 59040 Circular Economy—Product Circularity Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/82339.html?browse=tc (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- PCDS Product Circularity Data Sheet. Available online: https://pcds.lu/circularity-dataset-initiative/#members (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Hansen, K.; Mulhall, D.; Zils, M. Luxembourg as a Knowledge Capital and Testing Ground for the Circular Economy. National Roadmap for Positive Impacts. Tradition, Transition, Transformation; EPEA Internationale Umweltforschung GmbH: Luxembourg, 2014; Available online: https://www.luxinnovation.lu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Luxembourg-Circular-Economy-Study.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Schosseler, P.; Schroeder, J.; Mulhall, D. Implementing Circular Economy Principles in Economic Activity Areas in Luxembourg. In Circular Economy Disruptions, Past, Present and Future, International Symposium Abstracts; Exeter University: Exeter, UK, 2018; Available online: http://positiveimpakt.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Ecocirc_ZAE_LU_Rapport.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Cobuilder. Available online: https://cobuilder.com/en (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Madaster. Available online: https://madaster.com/ (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Toxnot. Available online: https://toxnot.com/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Cradle-to-Cradle Products Innovation Institute. Available online: https://www.c2ccertified.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- INCERT. Available online: https://www.incert.lu/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Luxembourg Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative, Creating a Digital Circularity Fingerprint for Products PHASE 1—FINAL REPORT; Ministry of the Economy: Luxembourg, 2020; p. 5. Available online: https://pcds.lu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/MECO_CEDataSet_PCDS_Public-27072020.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Morlet, A.; Blériot, J.; Opsomer, R.; Linder, M.; Henggeler, A.; Bluhm, A.; Carrera, A. Intelligent assets: Unlocking the circular economy potential. Ellen MacArthur Found. 2016, 1–25. Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/1tb7yclizlea-116tst/@/preview/1?o (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Braungart, M.; McDonough, W.; Bollinger, A. Cradle-to-cradle design: Creating healthy emissions–a strategy for eco-effective product and system design. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhall, D.; Braungart, M. Cradle to cradle criteria for the built environment. EKONOMIAZ. Rev. Vasca Econ. 2010, 75, 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- What Is Cradle-to-Cradle Certified? Available online: https://www.c2ccertified.org/get-certified/product-certification (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- EMF; McKinsey Company. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2012; p. 93. Available online: https://emf.thirdlight.com/link/x8ay372a3r11-k6775n/@/preview/1?o (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Standards Watch “Circular Economy Dataset”; ILNAS: Luxembourg, 2018.

- Luxembourg Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative, Creating a Digital Circularity Fingerprint for Products PHASE 1—FINAL REPORT; Ministry of the Economy: Luxembourg, 2020; p. 17. Available online: https://pcds.lu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/MECO_CEDataSet_PCDS_Public-27072020.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Ogunmakinde, O.E.; Egbelakin, T.; Sher, W. Contributions of the circular economy to the UN sustainable development goals through sustainable construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust over IP Foundation. Available online: https://www.trustoverip.org/ (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Luxembourg Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative, Creating a Digital Circularity Fingerprint for Products PHASE 1—FINAL REPORT; Ministry of the Economy: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 9–11. Available online: https://pcds.lu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/MECO_CEDataSet_PCDS_Public-27072020.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Luxembourg Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative, Creating a Digital Circularity Fingerprint for Products PHASE 1—FINAL REPORT; Ministry of the Economy: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 14–16. Available online: https://pcds.lu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/MECO_CEDataSet_PCDS_Public-27072020.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Mulhall, D.; Hansen, K.; Luscuere, L.; Zanatta, R.; Willems, R.; Boström, J.; Elfström, L.; Heinrich, M.; Lang, W. Buildings as Materials Banks (BAMB)-Framework for Materials Passports. 2017. Available online: https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/doc/1423282/file.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Luxembourg Circularity Dataset Standardization Initiative, Creating a Digital Circularity Fingerprint for Products PHASE 1—FINAL REPORT; Ministry of the Economy: Luxembourg, 2020; p. 3. Available online: https://pcds.lu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/MECO_CEDataSet_PCDS_Public-27072020.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Material Circularity Indicator (MCI). Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/material-circularity-indicator (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Global Battery Alliance Battery Passport. Global Battery Alliance. 2021. Available online: https://www.globalbattery.org/battery-passport/.https://www.globalbattery.org/battery-passport/ (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Circular Transition Indicators (CTI). World Buisiness Council for Sustainable Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/Programs/Circular-Economy/Metrics-Measurement/Circular-transition-indicators (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Fact Sheet, Circularity Facts Program. Underwriters Laboratories. Available online: https://www.ul.com/resources/circularity-facts-program (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- The Circular Cars Initiative. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/projects/the-circular-cars-initiative (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- The Alliance for Secure and Cross-Company Data Exchange in the Automotive Industry Is Picking Up Speed. Available online: https://www.press.bmwgroup.com/canada/article/detail/T0326861EN/the-alliance-for-secure-and-cross-company-data-exchange-in-the-automotive-industry-is-picking-up-speed?language=en (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Cradle to Cradle Certified™ Product Standard Version 4 Materials Passport. (Cradle-to-Cradle Product Innovation Institute). Available online: https://cdn.c2ccertified.org/resources/certification/v4_Materials_Passport_DRAFT_FOR_PUBLIC_COMMENT_FINAL_080319.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Circular Fashion. Available online: https://circular.fashion/en/ (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Mindful Materials. Available online: https://www.mindfulmaterials.com/ (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- ISO/TC 323 Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.iso.org/committee/7203984.html (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- BSI. The Rise of the Circular Economy, BS 8001—A New Standard Is. Available online: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/standards/benefits-of-using-standards/becoming-more-sustainable-with-standards/BS8001-Circular-Economy/ (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Platform CB ’23. Available online: https://platformcb23.nl/english (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- The International EPD System. Available online: https://www.environdec.com/home (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Blue Angel. Available online: https://www.blauer-engel.de/en (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Jang, M.; Yoon, C.; Park, J.; Kwon, O. Evaluation of hazardous chemicals with material safety data sheet and by-products of a photoresist used in the semiconductor-manufacturing industry. Saf. Health Work. 2019, 10, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelon, B.; Hasse, J.; Lajaunie, Q. ESG-Washing in the Mutual Funds Industry? From Information Asymmetry to Regulation. Risks 2021, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K. The Circular Economy: A Wealth of Flows; Ellen MacArthur Foundation Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Updates to the Cradle to Cradle Certified® Material Health Assessment Methodologies for Use in Version 4.0 Assessments. Cradle to Cradle Product Innnovation Institute. March 2021. Available online: https://cdn.c2ccertified.org/resources/certification/Changes_to_the_MHAM_for_use_in_v4_Assessments_031221.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).