India’s Renewable Energy Portfolio: An Investigation of the Untapped Potential of RE, Policies, and Incentives Favoring Energy Security in the Country

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Mission Solar JNNSM

- Sustainability of way of life;

- Economic growth that is cleaner;

- Lowering the GDP emission intensity;

- Raising the amount of electricity based on non-fossil fuels;

- Improving forests as a carbon sink;

- Adaptation;

- Finance management;

- Transfer of technology and capacity building.

3. Innovative Schemes

3.1. Green Corridor for Energy

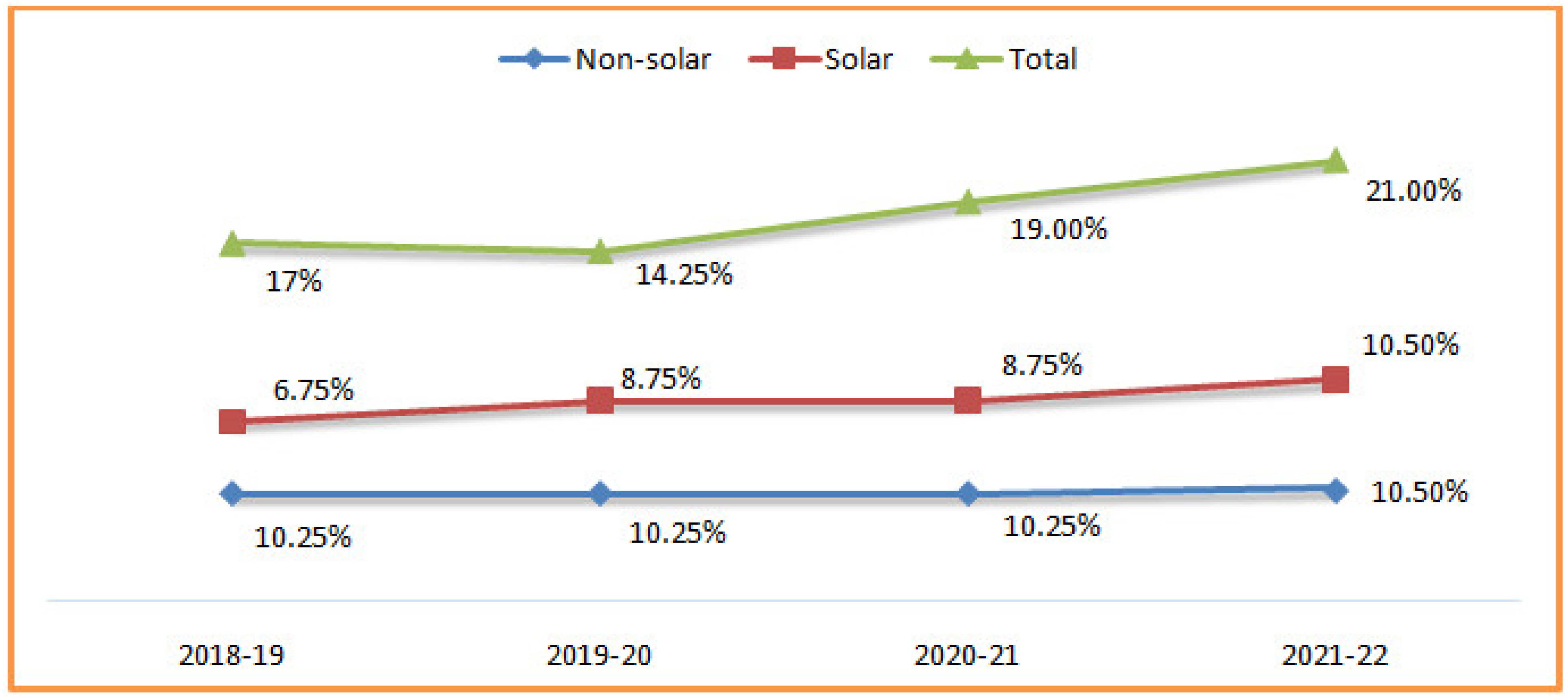

3.2. Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO)

3.3. Net Metering Policy and Virtual Net Metering

3.4. Raising of Bonds

3.5. International Solar Alliance

3.6. Solar Anti-Dumping

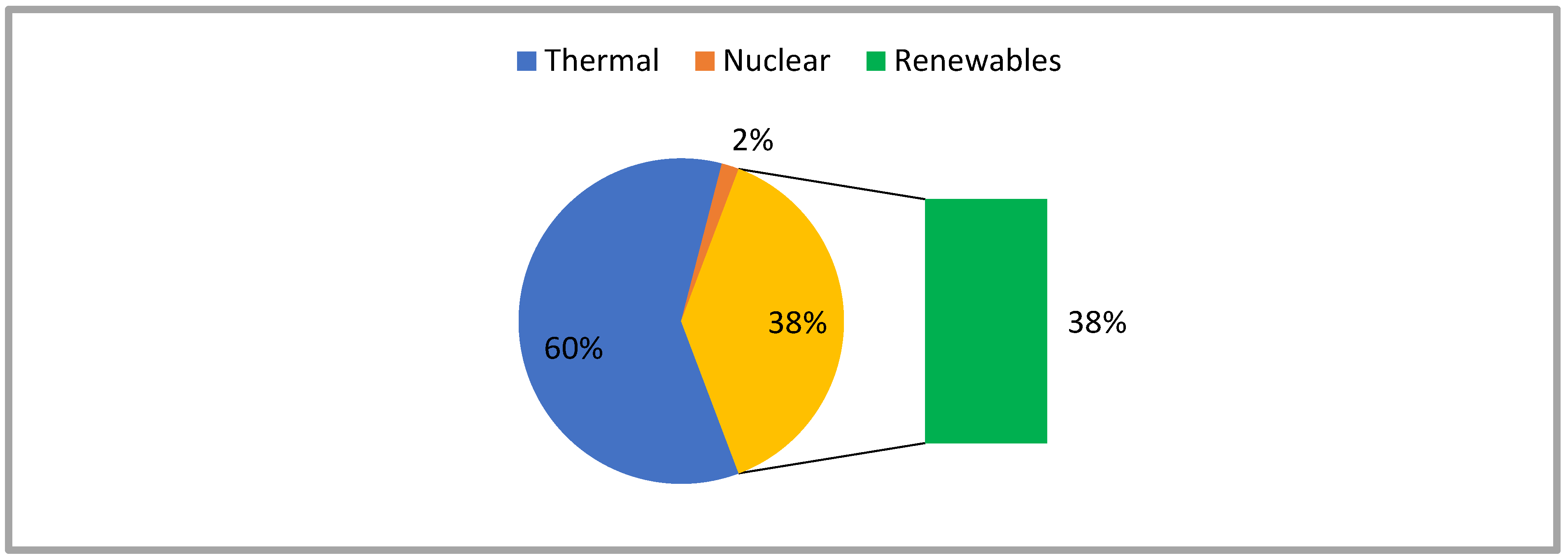

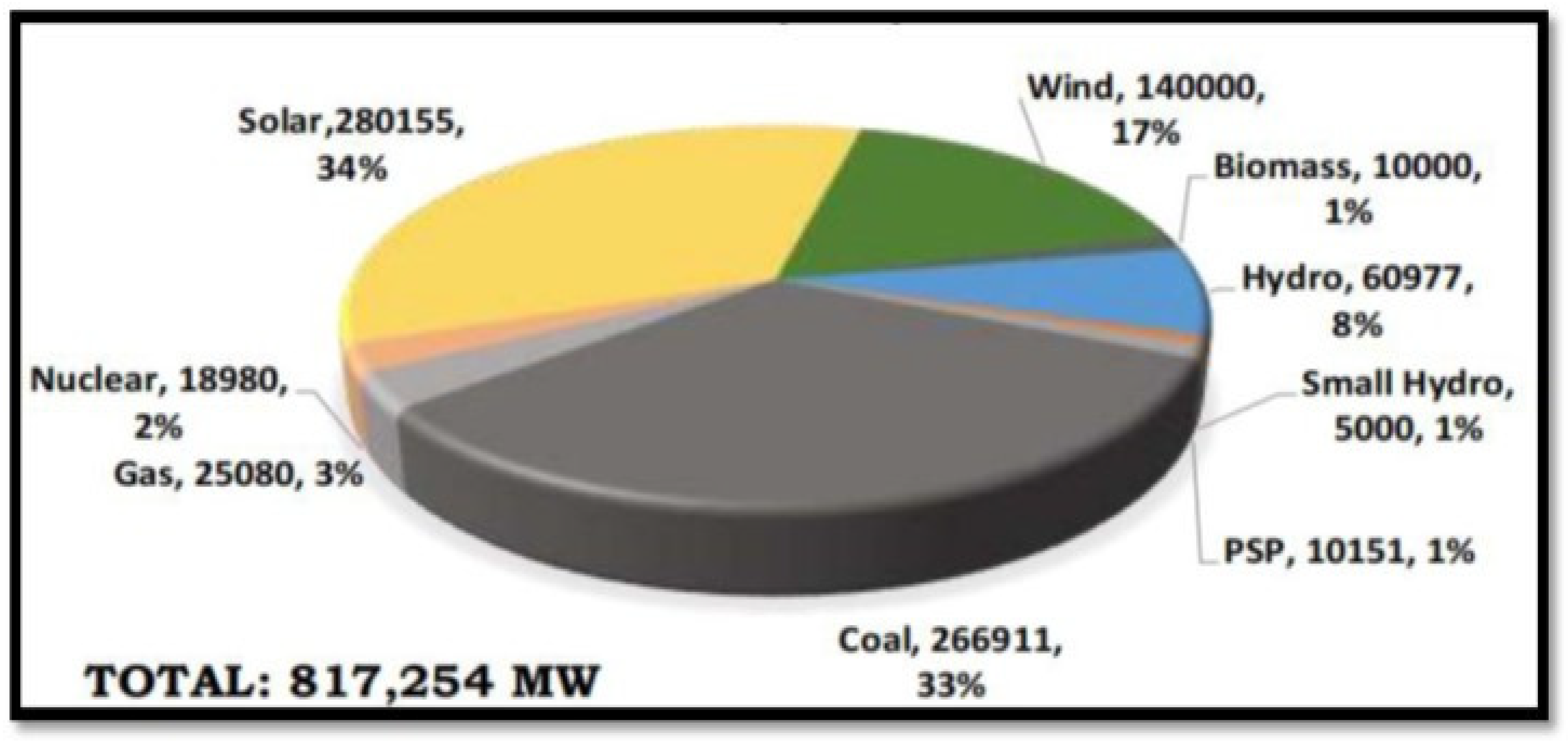

4. Power from Renewables in India

5. Incentives and Policies Favoring Installations

- Wind—695.51 GW (at 120 m hub height) and National Offshore, release of the Wind Energy Policy, preliminary evaluation at two locations (2000 MW), and investigation of the entire potential.

- Solar power—748.99 GW (the ratio of 60 km × 60 km wasteland, assuming 3% of it is made available, could produce all the power used in India in 2012.).

- Biomass power—44.85 GW (from surplus agro-biomass).

- Small hydropower (SHP)—211.33 GW (for ≤25 MW and being revised upward).

6. Key Milestones in the Sector

6.1. Solar and Wind Hybrid Systems

6.2. Decentralized Renewable Power Generation for Rural Electrification

6.3. Waiver of Inter-State Transmission Charges and Losses

6.4. Wind Power

- Modifications to the “Guidelines for Tariff-Based Competitive Bidding Procedure for Purchase of Electricity from Grid Connected Wind Solar Hybrid Projects.”

- As of the amendment dated 9 March 2022, the authorized representatives of clients may conduct the bidding procedure on their behalf.

- The hybrid project commissioning timetable was extended from 18 to 24 months.

- The amendment from 2 November 2022 rationalizes the obligation involving to a delay in commissioning due to a delay for LTA operationalization.

- The Ministry of Finance notified that the CCDC for a number of wind turbine components has been extended until 31 March 2023.

6.5. Solar Parks

6.6. Safeguard Duty

6.7. PM-KUSUM

- Under Component A, on their uncultivated or barren lands, single farmers, cooperatives, panchayets, and farmer producer organizations (FPOs) will construct renewable power solar PV plants with a capacity that ranges from 500 KW to 2 MW. The DISCOMs will acquire the generated power at a rate set by the relevant SERC. The program will give rural landowners access to a reliable and ongoing source of revenue. The distribution company will receive performance-based incentives at a rate of 0.40 INR per unit purchased or 6.6 INR lakh per MW of installed capacity, whichever is less, for a period of five years starting on the Commercial Operation Date.

- Under Component B, 7.5 HP standalone solar pumps are supported for installation by individual farmers.

- Under Component C, individual farmers will receive funding from the program to solarize pumps with a maximum HP of 7.5, and solar power up to double the pump capability in kW is permitted. The energy created can be used by the farmer to power irrigation systems, and any extra energy left over can be sold to the distribution company. This will make it easier for the farmers to earn additional cash. States may also choose to solarize at the feeder level, where a single solar plant is erected using the RESCO and CAPEX modes to supply power to a single or multiple agriculture feeders.

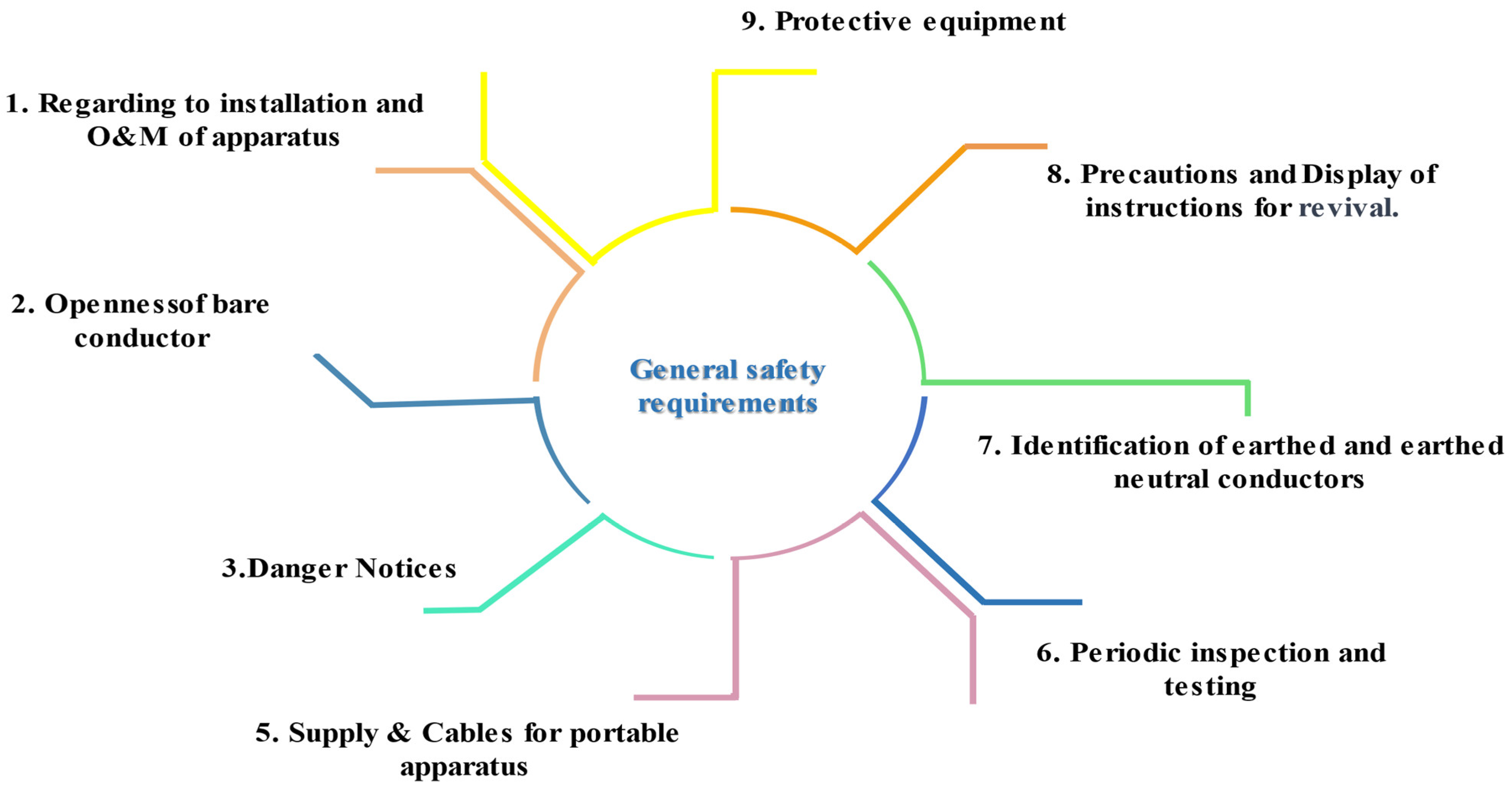

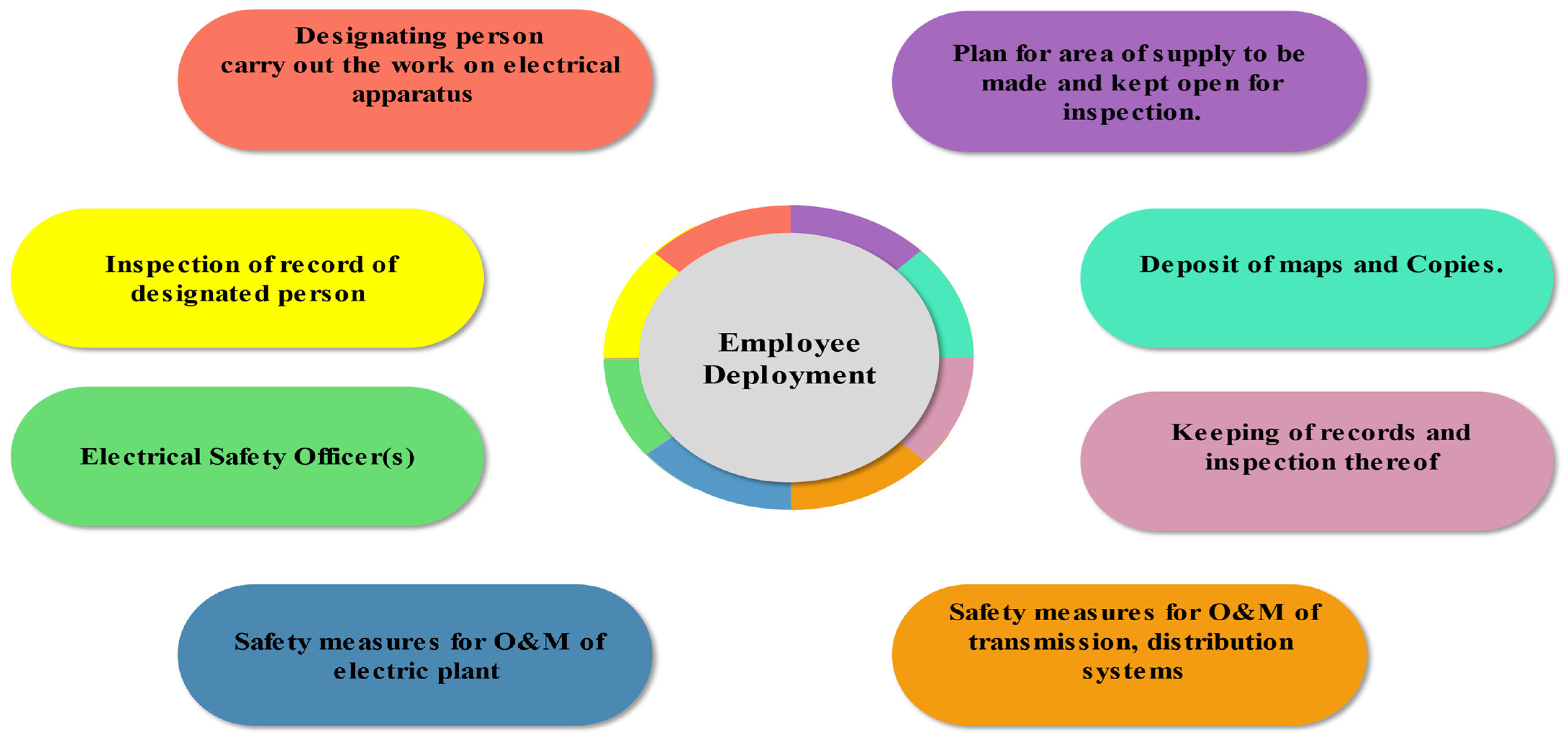

6.8. Organization Working for the Development of the Standards and Regulations

7. The Way Forward for the Target of 500 GW by 2030

8. Key Challenges in the Sector

8.1. Declining Wind Installations

8.2. State and Central Subsidy on Solar Roof Top

8.3. Barrel Land Acquisition

8.4. Transmission Challenges

8.5. Domestic Solar Panel Manufacturing

8.6. Discontinuation of Customs Duty Exemption (CCDC)

8.7. Supply Disruption and COVID-19 Impact

8.8. Grid Integration Challenges

- Weak inter-regional electricity transmission lines as a result of several ongoing outages (both planned and unplanned);

- High loading on the 400 kV Bina–Gwalior–Agra link;

- Inadequate response by State Load Dispatch Centers (SLDCs) to the instructions of Regional Load Dispatch Centers (RLDCs) to reduce over-withdrawal by the Northern Region utilities and under-withdrawal/excess generation by the Western Region utilities;

- Loss of the 400 kV Bina–Gwalior link due to mis-operation of its protection system.

8.9. Demand of the Large-Scale Energy Storage Systems

8.10. Solar Project Study on Dynamic and Static Modeling Report

8.11. High Reactive Power Demand Due to PPC Malfunctioning

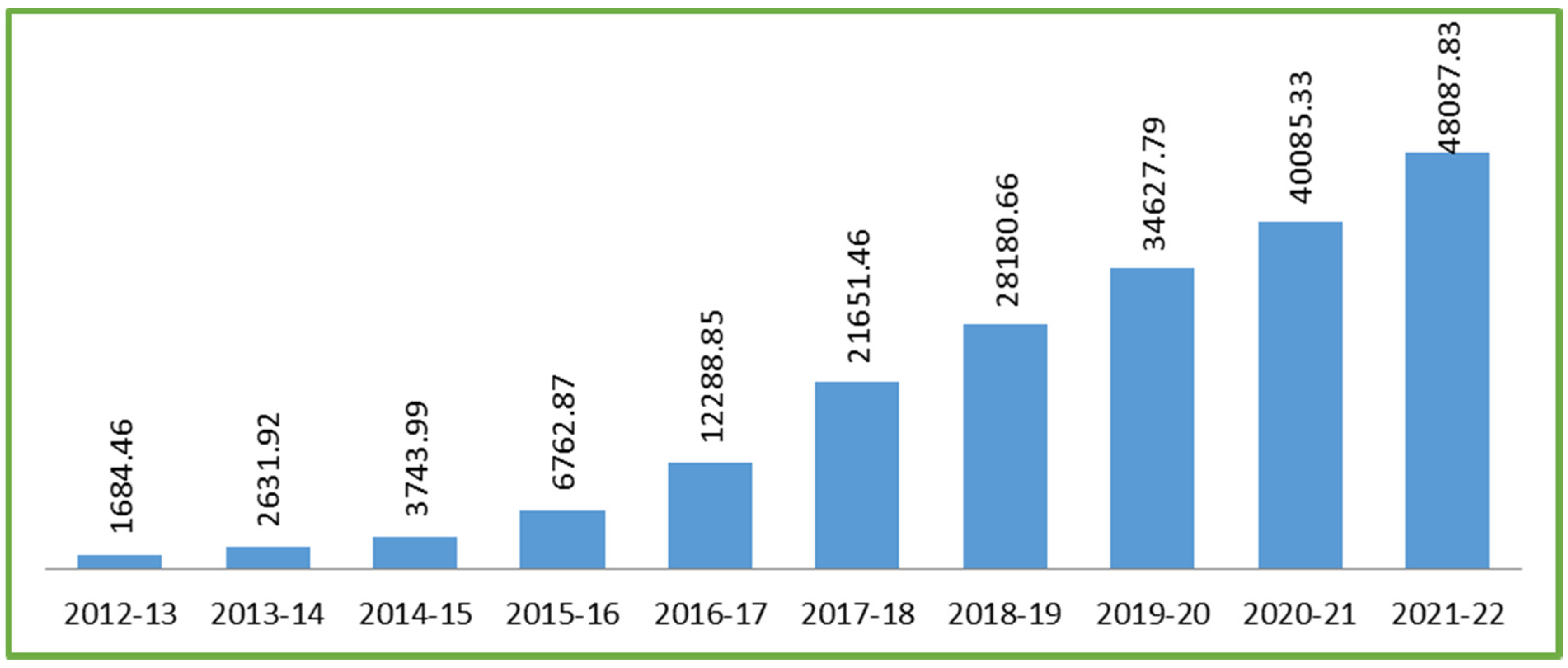

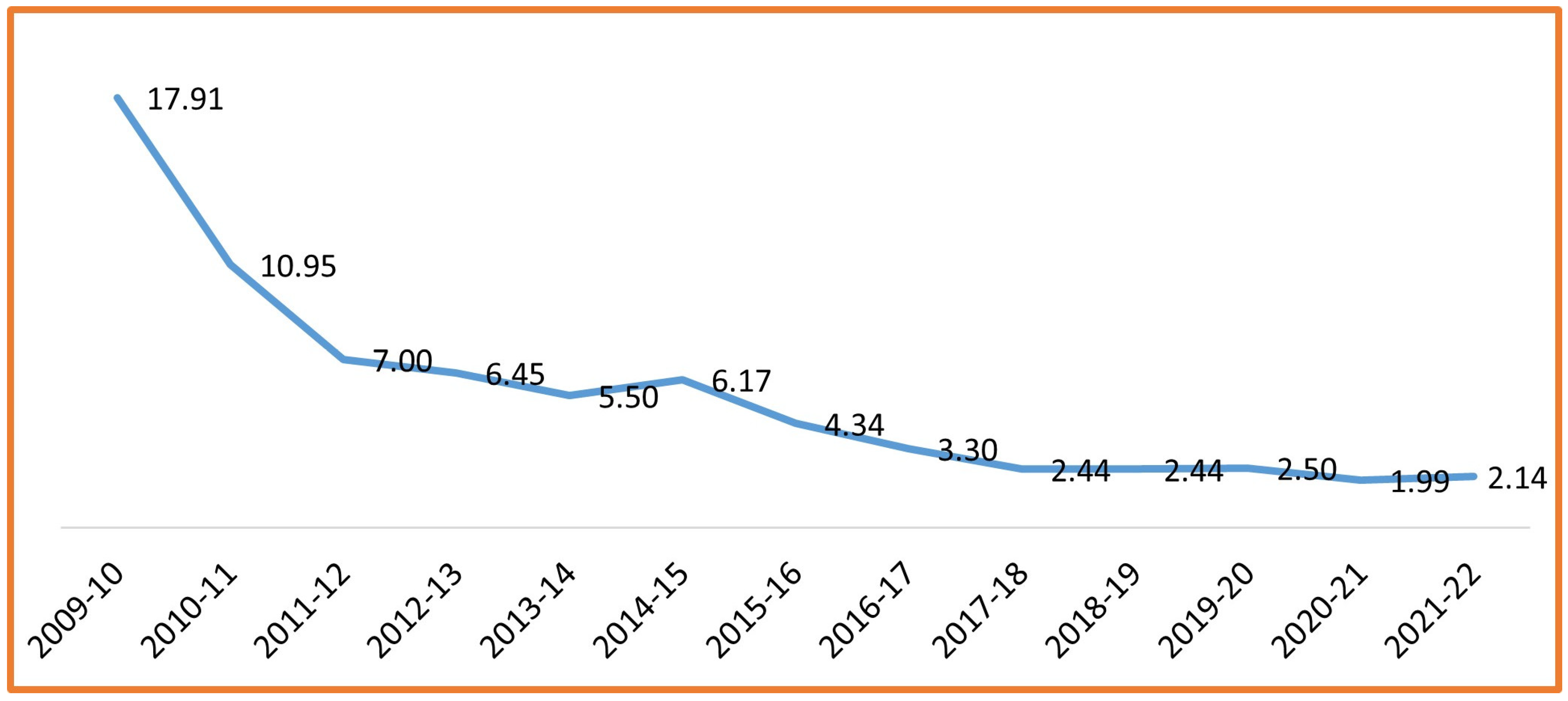

8.12. Tariffs Steep Fall and Exponential Rise

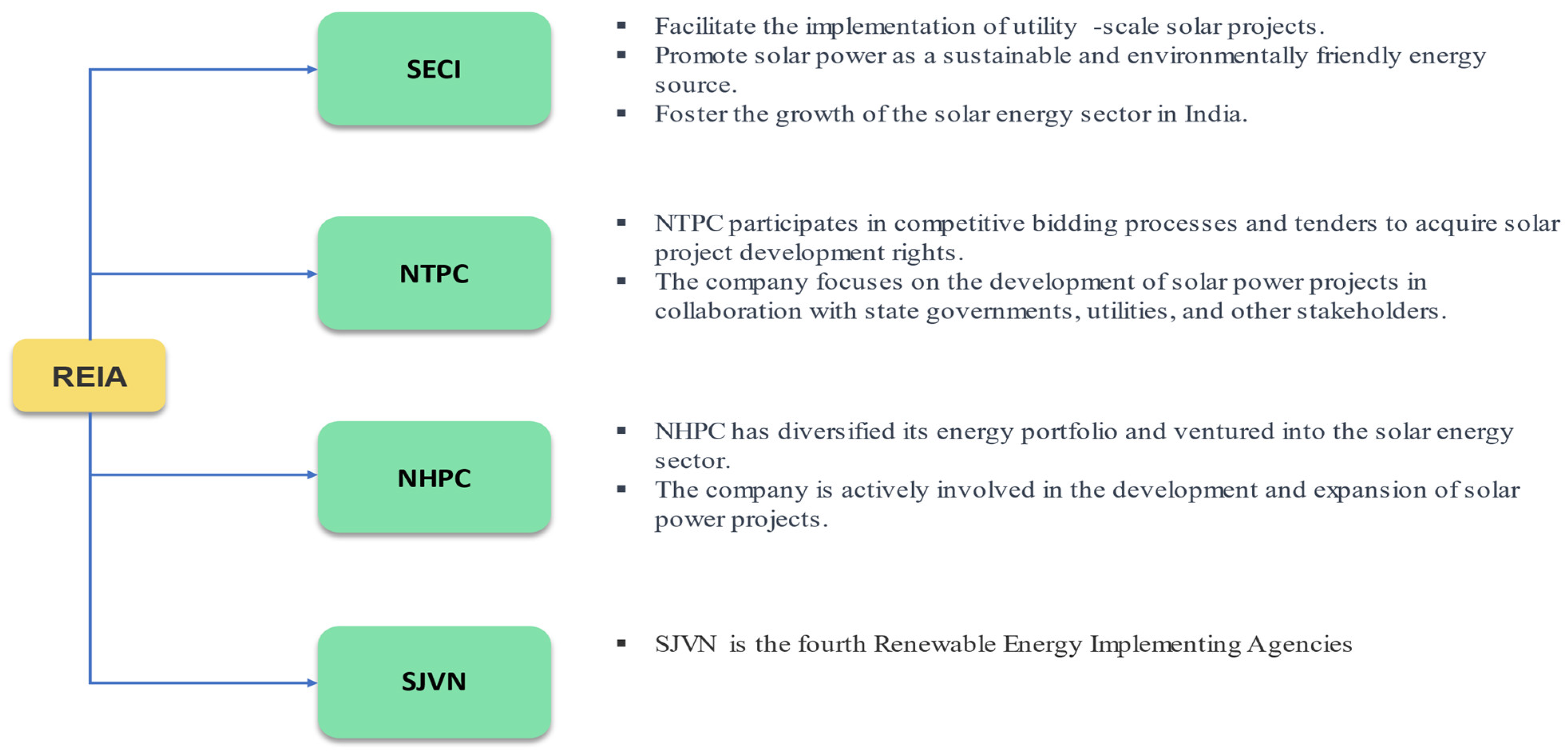

9. Institutions Supporting the MNRE and Key Roles

10. Conclusions

- The main focus is on clean and green energy, free from carbon emissions, which requires a centralized space or portal for policy planning, and its implementation should be updated from time to time.

- The provision for the earning by the renewable energy plants needs to be a priority. Via good initiatives, such as PM-KUSUM yojana, the government should infuse the funds or provide subsides or loans for the development of solar PV plants. The agriculture tariff also can be subsided for the development of the plant.

- Hazards to power systems can be caused by individuals, the surroundings, technological equipment, or the programming. These dangers occasionally have disastrous impacts that can cause the disruption of power and cause grid failures and blackouts. To manage and reduce the possibility of such occurrences, there is a critical need for emergency management across the power sector.

- The investment for modernization and to ensure grid security needs to be actively pursued to ensure the security of the data, because data communication is the most important part of the scheduling and forecasting of the generating plant. This investment will create jobs for researching the data and system security.

- The Indian government has appropriately recognized private sector involvement as a key tool for enhancing the power sector.

- The emphasis on regulatory improvements and project efficiencies must be prioritized. On the efficiency front, there is a continuing need to concentrate on improving efficiencies throughout the repowering method, supply chain management, design, manpower handling, fuel and transportation costs, power purchase costs, and the efficiency of power-producing businesses. The government has improved tariff designs, which will surely reflect market growth and provide flexibility in subsidy provision, as funding of the viability gap in early RE projects is required on the regulatory side.

- Presenting an outlook for the future and the path for the nation’s manufacturing plan will ease the dependency on the import of PV panels, inverters, and WTGs. This will also create a big market for Asia as a manufacturing hub of RE-based technologies and will create job opportunities for the new generation.

- Repowering. Repowering refers to the ability to generate more power from the same plant, utilizing the same land and distribution infrastructure. Repowering using solar can be termed as the method of exchanging aging equipment or generating material used in solar PV panels with modern ones. These changes can have a bigger nameplate power or increase efficiency, resulting in an increase in net power production. Because of the space constraints, repowering of the RE projects, especially solar plants having MW capacity, will require the government to make policies for tracing and technically implementing the suggestions. This will enhance the productivity of the RE plants with the same resources.

- Transmission via CTUs and STUs is a stem and DISCOMs are the branch of the system for the rooted power plants that need to be ranked by the ministry. This will definitely expand from private to public DISCOMs, and the ranking will create the competition for the collection of the revenue for the DISCOMs’ management company of the state, and also enable CTUs and STUs to enhance their network.

- The acquisition of barren land for solar projects is currently a key challenge faced by the SPPDs because a huge quantum of land will be required for the solar plants. To help overcome this challenge, the central government introduced the solar park scheme, wherein the land and connectivity infrastructure is provided by the government on the payment of a fixed lease amount.

- Subsidy for residential rooftop plants at a fixed benchmark cost; the central government provides 40% and some state governments also contribute over this ratio. This initiative, to be taken by all state governments, will attract more users, which will directly contribute to the achievement of the target of 500 GW.

- Right of way (RoW) approval before charging of the plants, the delay in consent to this is a very serious issue, and this approval requires many permissions from forest owners, the national highway authority, and operators of telecommunication, defense, and railway services. The permissions required from all concerned departments are applicable to each case, and the development of a centralized portal that includes the interventions for all departments at the same time as the application will smooth the process.

- Import duty benefits: The country is still dependent on the import of the latest technology for centralized inverters and string inverters. Until the infrastructure for the manufacturing and testing of these units, PLC, communication, and protection relays are developed, the government should give import duty exemption. This will attract foreign investors and achieve the large quantum scale needed for connection to the grid on time.

- High reactive power demand due to PPC malfunctioning: The government should not impose heavy duties and surcharges due to reactive power demand, as this concern occurs entirely due to the failure of PPC (a power plant controller). Case-by-case relaxations should be provided by DISCOMs in support of RE developers.

- It can be seen in the graphs that all of the above factors cause a rise in the tariffs after the corona effect. Relaxations should be provided by the key stakeholders in favor of developers for promoting renewable energy.

- The majority of the compliances need to be fulfilled before the charging and commissioning of the RE plants, and are mostly associated with the government authorities of the concerned departments, as listed above. It is recommended to develop and promote a single-window monitoring portal for all applications, with intervention by the most senior authorities in case of any delay in the process. The portal should be regularly monitored for any due compliance, if any; then, appropriate action can be taken, even for the developer, and also in the form of a penalty.

- Finally the solar PV plants with complete installed fulfilling all the compliances for charging should not be curtailed for their power generation and injection to grid. Ultimately, a generation loss is a big loss to the nation, and a committee should be formed to examine if the matter is subject to legal oversight or caused by any irrelevant issues. In these cases, the Commercial Operation of the Plant (COD) should not be awarded for the project until the issue is resolved.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| NSM | Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission |

| MNRE | Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, Government of India |

| MoP | Ministry of Power, Government of India |

| CEA | Central Electricity Authority |

| CUF | Capacity Utilization Factor |

| RE | Renewable Energy |

| REC | Renewable Energy Certificate |

| RPO | Renewable Purchase Obligation |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| PMKUSUM | Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha Evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan |

| GW | Gigawatt |

| MW | Megawatt |

| NIP | National Infrastructure Pipeline |

| FY | Financial Year |

| COP | Conference of Parties |

| NTP | National Tariff Policy |

| NEP | National Electricity Policy |

| INDC | Intended Nationally Determined Contributions |

| DISCOMs | Electricity Distribution Companies |

| GUVNL | Gujarat Urja Vikash Nigam Limited |

| CTU | Central Transmission Utility |

| STU | State Transmission Utility |

| POWERGRID | Power Grid Corporation of India Limited |

| ADB | Asian Development Bank |

| WB | World Bank |

| HVDC | High Voltage Direct Current |

| CERC | Central Electricity Regulatory Commission |

| SERC | State Electricity Regulatory Commissions |

| IREDA | Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency |

| IPGCL | Indraprastha Power Generation Company Limited |

| POSOCO | Power System Operation Corporation Limited |

| GEC | Green Energy Corridor |

| IPP | Independent Power Producer |

References

- Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1885147#:~:text=as%20on%2031.10.-,2022.,the%20period%20Jan%20to%20Oct (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Urhekar, S.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, S.D.; Meena, R.S. Yield enhancement analysis of installed solar power projects in the country: An assessment for productive utilization of the power through Repowering. BioGecko 2023, 12, 76–794. Available online: https://biogecko.co.nz/admin/uploads/11593_Biogeckoajournalfornewzealandherpetology_02-08-45.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1882145 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- MNRE: Year End Review-2020. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1685046 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Press Information Bureau. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1768712 (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- National Infra Structure Pipeline, (NIP/Vol2). Available online: https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Report%20of%20the%20Task%20Force%20National%20Infrastructure%20Pipeline%20%28NIP%29%20-%20volume-ii_1.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Behuria, P. The politics of late development in renewable energy sectors: Dependency and contradictory tensions in India’s National Solar Mission. World Dev. 2020, 126, 104726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.D.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urpelainen, J.; Yang, J. Global patterns of power sector reform, 1982–2013. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 23, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, P.K. Energy indices: A risk factor or not in the financial sector. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, G.; Sinha, S. Outlook on the Indian scenario of solar energy strategies: Policies and challenges. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, S.; Shrivastva, R.; Sharma, V.; Ramasamy, P. Overview of the initiatives in renewable energy sector under the national action plan on climate change in India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, S.; Sharma, S.; Verma, A. Economic and environmental effectiveness of renewable energy policy instruments: Best practices from India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, G. The development of renewable energy power in India: Which policies have been effective? Energy Policy 2012, 45, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutshack, V. New and renewable energy social enterprises accessing government support: Findings from India. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MNRE, Physical Progress. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/the-ministry/physical-progress (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Kumar, J.C.R.; Majid, M.A. Renewable energy for sustainable development in India: Current status, future prospects, challenges, employment, and investment opportunities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PIB. Published on 1 December 2021. Available online: https://static.pib.gov.in/WriteReadData/specificdocs/documents/2021/dec/doc202112101.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- SECI, Uploads. Available online: https://www.seci.co.in/upload/static/files/mission_document_JNNSM(1).pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- PIB. Published on 2 October 2015. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/newsite/printrelease.aspx?relid=128403 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- MNRE, Annual Report 21-2022. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/img/documents/uploads/file_f-1671012052530.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- PIB. Published on 6 January 2022. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1788011 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- MNRE. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/solar/rpo/ (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- MOP. Available online: https://powermin.gov.in/sites/default/files/Renewable_Purchase_Obligation_and_Energy_Storage_Obligation_Trajectory_till_2029_30.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- MNRE. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/img/documents/uploads/file_f-1664883789129.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- MNRE. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/isa/ (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://www.pv-magazine-india.com/2022/11/14/india-terminates-solar-cell-anti-dumping-probe/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chains/executive-summary (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- The Economic Times, Published 13 November 2022. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/renewables/india-terminates-anti-dumping-probe-into-solar-cell-imports-from-china-thailanlandvietnam/articleshow/95484210.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- ISA. Available online: https://isolaralliance.org/uploads/docs/e90583619e442a2b277b445050eeac.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/readersblog/pracin-jain-academy/india-has-immense-potential-of-solar-energy-29567/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- MNRE. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/sites/default/files/webform/notices/National-Wind-Solar-Hybrid-Policy.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Thapar, S. Centralized vs. decentralized solar: A comparison study (India). Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economic Times, Publised 2 December 2022. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/power/power-ministry-waives-inter-state-transmission-system-charges-for-new-hydro-power-projects/articleshow/95944110.cms (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1880517 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- GOI. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1885147 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- SolarQuarter. Available online: https://solarquarter.com/2023/03/18/india-approves-57-solar-parks-with-39-28-gw-capacity-but-many-delayed/ (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- MNRE. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/solar/schemes (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/sme-sector/to-impose-or-not-to-impose-anti-dumping-duty-budgets-retrospective-amendment-may-impact-domestic-industry/articleshow/98292184.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- CEA (Measures Relating to Safety and Electric Supply) Regulations, 2010 Amendment-Safety Aspects with Respect to the Charging Stations. Available online: https://cea.nic.in/regulations-category/measures-relating-to-safety-and-electric-supply/?lang=en (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- CEA. “Technical Standards for Connectivity of Distributed Generation Resources 2019” Regulation. Available online: https://cea.nic.in/regulations-category/connectivity-of-distributed-generation-resources/?lang=en (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Batra, P.; Sharma, S.; Gupta, P.; Arya, B.K.; Rajput, A.K.; Menghani, V. Long Term Planning for Indian Power Sector with Integration of Renewable Energy Sources. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 7–11 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Central Electricity Authority, Report on Optimal Generation Capacity Mix for 2029-30. Available online: https://cea.nic.in/wpcontent/uploads/notification/2023/05/Optimal_mix_report__2029_30_Version_2.0__For_Uploading.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1897774 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Deshwal, D.; Sangwan, P.; Dahiya, N. How will COVID-19 impact renewable energy in India? Exploring challenges, lessons and emerging opportunities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 77, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.businesstoday.in/industry/energy/story/power-failure-in-north-india-affects-7-states-33717-2012-07-30 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://mercomindia.com/mercom-exclusive-solar-tariffs-indiafallen-73-percent-since-2010/ (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/img/documents/uploads/file_f-1682405289970.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

| Category | Target by December 25 (in GW) | Actual Achievement until October 19 (in GW) | Capacity to Be Added by FY | Capex over FY20-23 (Rs Cr) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar power | 149.7 | 31.4 | 118 | 472,000 | ||

| Wind power | 96.99 | 37.09 | 59.90 | 419,300 | ||

| Small hydropower | 7 | 4.65 | 2.35 | 23,500 | ||

| Biopower | 12.04 | 9.94 | 2.10 | 14,700 | ||

| Total | 265.73 | 83.38 | 182.35 | 929,500 | ||

| Capital expenditure over FY20 to FY25 | ||||||

| INR crore | FY20 | FY22 | FY23 | FY24 | FY25 | Total |

| Capital Expenditure | 30,500 | 151,000 | 144,000 | 170,000 | 217,000 | 929,500 |

| Panchamrit | India’s Commitment to Climate Action |

|---|---|

| Panch 1 of 5 | Reach 500GW energy from non-fossil fuels by 2030 |

| Panch 2 of 5 | By 2030, renewable energy will provide 50% of India’s energy needs |

| Panch 3 of 5 | Between now and 2030, the anticipated global carbon emissions must be reduced by one billion tonnes |

| Panch 4 of 5 | By 2030, the economy’s intensity of carbon will have decreased by 45% from 2005 levels |

| Sr. No. | PPA Signed | Applicable ISTS Charges | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | On or before 30 June 2025 | Nil | PPA signed and construction work is awarded |

| 2 | 1 July 2025 to 30 June 2026 | 25% | |

| 3 | 1 July 2026 to 30 June 2027 | 50% | |

| 4 | 1 July 2027 to 30 June 2028 | 75% | |

| 5 | 1 July 2028 | 100% ISTS fees will be charged |

| SR. NO. | Component | Capacity | Numbers Achieved | Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. Solar Power Plant | Decentralized ground-mounted solar power plants with grid connectivity | 25.25 MW | 10,000 MW |

| 2 | B. Solar Pump | Standalone solar-powered agriculture pumps | 75,000 | 20 Lakh |

| 3 | C. Solar Pump | Solarization of currently installed grid-connected solar-powered agriculture pumps | 1000 | 15 Lakh |

| S. No. | Bidding Agency/Location | Scheme | E-Reverse Auction (Year and Month) | Capacity Offer (MW) | Highest Bid (INR/KWh) | Lowest Bid (INR/KWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariff discovered in the year 2017 under various schemes/projects | ||||||

| 1 | RUMSL—Madhya Pradesh | State Scheme | 2017-February | 750 | 2.979 | 2.97 |

| 2 | NTPC—Andhra Pradesh | Bundling Scheme | 2017-April | 250 | 3.15 | 3.15 |

| 3 | SECI—Rajasthan-Bhadla Ph IV Solar Park | VGF Scheme | 2017-May | 250 | 2.63 | 2.62 |

| 4 | SECI—Rajasthan—Bhadla Ph III Solar Park | VGF Scheme | 2017-May | 500 | 2.45 | 2.44 |

| 5 | TANGEDCO—Tamil Nadu | State Scheme | 2017-July | 1500 | 3.97 | 3.47 |

| 6 | GUNL—Gujarat | State Scheme | 2017-August | 500 | 2.67 | 2.65 |

| 8 | SECI—Rajasthan—Bhadla Ph IV Solar Park | VGF Scheme | 2017-December | 250 | 2.49 | 2.48 |

| 9 | SECI—Rajasthan—Bhadla Ph III Solar Park | VGF Scheme | 2017-December | 500 | 2.48 | 2.47 |

| Tariff discovered in the year 2018 under various schemes/projects | ||||||

| 1 | SECI—Gujarat | State Scheme | 2018-March | 500 | 3.06 | 2.98 |

| 2 | KREDL—Karnataka—Pavagda Solar Park | State Scheme | 2018-March | 550 | 2.93 | 2.91 |

| 3 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme | 2018-May | 1000 | 2.72 | 2.71 |

| 4 | APDCL—Assam | State Scheme | 2018-June | 85 | 3.7 | 3.17 |

| 5 | SECI—Uttar Pradesh—Solar Park | VGF Scheme | 2018-June | 125 | 3.38 | 3.32 |

| 6 | SECI—Andhra Pradesh-Kadapa Solar Park | VGF Scheme | 2018-July | 750 | 2.71 | 2.7 |

| 7 | UPNEDA—Uttar Pradesh | State Scheme | 2018-July | 1000 | 3.55 | 3.48 |

| 8 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS-I Scheme | 2018-July | 2000 | 2.54 | 2.44 |

| 9 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS-II Scheme | 2018-July | 3000 | 2.71 | 2.44 |

| 10 | KREDL—Karnataka—Pavagada Solar Park | State Scheme | 2018-July | 500 | 2.85 | 2.85 |

| 11 | SECI—Odisha | State Scheme | 2018-July | 200 | 3.2 | 2.79 |

| 12 | NTPC—Anywhere in India | ISTS Scheme | 2018-August | 2000 | 2.6 | 2.59 |

| 13 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme | 2018-September | 500 | 2.45 | 2.44 |

| 14 | KREDL—Karnataka | State Scheme | 2018-October | 150 | 2.92 | 2.92 |

| 15 | UPNEDA—Uttar Pradesh | State Scheme | 2018-October | 500 | 3.23 | 3.13 |

| 16 | SECI—Floating in Uttar Pradesh | State Scheme | 2018-November | 150 | 3.29 | 3.29 |

| 17 | UPNEDA—Uttar Pradesh | State Scheme | 2018-December | 550 | 3.08 | 3.02 |

| Tariff discovered in the year 2019 under various schemes/projects | ||||||

| 1 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme | 2019-February | 500 | 2.68 | 2.55 |

| 2 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme | 2019-February | 1000 | 2.75 | 2.74 |

| 3 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme | 2019-February | 700 | 2.89 | 2.84 |

| 4 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS—III Bidding | 2019-February | 1200 | 2.61 | 2.55 |

| 5 | SECI—Rajasthan Non-Solar Park | State Scheme | 2019-March | 750 | 2.49 | 2.48 |

| 6 | SECI—Dondaicha Solar Park Maharashtra | State Scheme | 2019-May | 250 | 2.91 | 2.87 |

| 7 | GUVNL—Gujarat—Raghanesda Solar Park | State Scheme | 2019-May | 500 | 2.7 | 2.65 |

| 8 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph V | 2019-May | 250 | 2.75 | 2.75 |

| 9 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS-IV Bidding | 2019-June | 1200 | 2.55 | 2.54 |

| 10 | UPNEDA—Uttar Pradesh | State Scheme | 2019-June | 500 | 3.05 | 3.02 |

| 11 | SECI—Rajasthan | State Scheme Tranche II | 2019-June | 750 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 12 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS-V Bidding | 2019-August | 1200 | 2.65 | 2.53 |

| 13 | HPPC—Haryana | State Scheme | 2019-August | 300 | 2.99 | 2.82 |

| 14 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS-VI Bidding | 2019-October | 1200 | 2.72 | 2.71 |

| 15 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph VI | 2019-October | 200 | 2.65 | 2.65 |

| 16 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph VII | 2019-October | 750 | 2.75 | 2.75 |

| 17 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme MSEDCL Ph IV | 2019-December | 500 | 2.9 | 2.89 |

| Tariff discovered in the year 2020 under various schemes/projects | ||||||

| 1 | UPNEDA—Uttar Pradesh | State Scheme | 2020-Jan | 500 | 3.18 | 3.17 |

| 2 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS-VIII Bidding | 2020-Feb | 1200 | 2.51 | 2.5 |

| 3 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph VIII | 2020-Mar | 750 | 2.64 | 2.61 |

| 4 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme MSEDCL Ph V | 2020-Mar | 500 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| 5 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme MSEDCL Saur Krishi Vahini | 2020-Mar | 1350 | 3.3 | 3.28 |

| 6 | NHPC—Anywhere in India | ISTS Bidding | 2020-Apr | 2000 | 2.61 | 2.55 |

| 7 | SECI—Anywhere in India | ISTS-IX Bidding | 2020-Jun | 2000 | 2.38 | 2.36 |

| 8 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph IX | 2020-August | 700 | 2.81 | 2.78 |

| 9 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph X | 2020-October | 100 | 2.73 | 2.73 |

| 10 | KSEB—Kerala | State Scheme | 2020-Nov | 200 | 2.97 | 2.97 |

| 11 | SECI—Rajasthan | State Scheme Tranche III | 2020-Nov | 1070 | 2.01 | 2 |

| 12 | ISTS—Hybrid Anywhere in India | ISTS-Hybrid Bidding Tr III | 2020-December | 1200 | 2.42 | 2.41 |

| 13 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph XI | 2020-December | 500 | 1.99 | 1.99 |

| Tariff discovered in the year 2021 under various schemes/projects | ||||||

| 1 | GUVNL—Gujarat | State Scheme GUVNL Ph XII | 2021-Mar | 500 | 2.21 | 2.2 |

| 2 | NTPC—Rajasthan | Nokh Solar Park | 2021-Mar | 190 | 2.25 | 2.25 |

| 3 | UPNEDA—Uttar Pradesh Solar Park | State Scheme | 2021-Mar | 200 | 2.69 | 2.68 |

| 4 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme—Hybrid | 2021-Jul | 500 | 2.62 | 2.62 |

| 5 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme MSEDCL Ph V | 2021-Jul | 500 | 2.43 | 2.43 |

| 6 | RUMSL—Madhya Pradesh | State Scheme | 2021-Jul | 550 | 2.45 | 2.44 |

| 7 | RUMSL—Madhya Pradesh | State Scheme | 2021-Jul | 450 | 2.33 | 2.35 |

| 8 | RUMSL—Madhya Pradesh | State Scheme | 2021-August | 500 | 2.15 | 2.14 |

| 9 | BREDA—Bihar | State Scheme | 2021-August | 250 | 3.12 | 3.11 |

| 10 | SECI—Rajasthan | State Scheme Tranche IV | 202-December | 1785 | 2.18 | 2.17 |

| Tariff discovered in the year 2022 under various schemes/projects | ||||||

| 1 | UPNEDA—Uttar Pradesh | State Scheme | 2022-January | 200 | 2.98 | 2.98 |

| 2 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | Kusum Scheme | 2022-January | 444 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| 3 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | Agriculture feeder Scheme | 2022-January | 1250 | 3.1 | 3.05 |

| 4 | SECI—Karnataka | State Scheme Tranche X | 2022-February | 200 | 2.37 | 2.35 |

| 5 | SECI—Himachal Pradesh | State Scheme Floating solar | 2022-February | 15 | 3.26 | 3.26 |

| 6 | GUVNL—Gujrat | State Scheme Tranche XIII | 2022-March | 500 | 2.29 | 2.29 |

| 7 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | Agriculture Feeder Scheme | 2022-May | 865 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| 8 | SECI Pan India | 2022-May | 1200 | 2.54 | 2.53 | |

| 9 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | Kusum Scheme | 2022-June | 445 | 3.1 | 3.05 |

| 10 | GUVNL—Gujrat | State Scheme Tranche XIV | 2022-July | 500 | 2.31 | 2.3 |

| 11 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | Kusum Scheme | 2022-August | 431 | 3.1 | 2.3 |

| 12 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme Tranche VII | 2022-September | 500 | 2.91 | 2.9 |

| 13 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | 2022-September | 500 | 2.83 | 2.82 | |

| 14 | GUVNL—Gujrat | State Scheme Tranche XVI | 2022-September | 750 | 2.66 | 2.49 |

| 15 | RUMSL—Madhya Pradesh | State Scheme Floating Tranche II | 2022-October | 750 | 3.04 | 3.03 |

| 16 | MSPGCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme Floating | 2022-November | 105 | 3.93 | 3.93 |

| 17 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme Tranche IX | 2022-December | 500 | 2.97 | 2.9 |

| 18 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | 2022-December | 250 | 9 | 9 | |

| Tariff discovered in the year 2023 under various schemes/projects | ||||||

| 1 | GUVNL—Gujrat | 2023-January | 500 | 2.52 | 2.51 | |

| 2 | RECDCL Pan India | 2023-April | 250 | 2.56 | 2.55 | |

| 3 | RECDCL Pan India | 2023-April | 500 | 2.7 | 2.69 | |

| 4 | SECI Pan India | 2023-April | 1200 | 4.73 | 4.64 | |

| 5 | MSEDCL—Maharashtra | State Scheme Tranche X | 2023-April | 500 | 2.88 | 2.87 |

| 6 | GUVNL—Gujrat | State Scheme Tranche XIX | 2023-April | 500 | 2.75 | 2.71 |

| Sr. No. | Organization | Role in the Growth of Renewable Energy | |

| 1 | MNRE | Ministry of New and Renewable Energy | The ministry’s overarching goal is to create and implement new, renewable energy sources to support the nation’s energy needs. |

| 2 | NISE | National institute of Solar Energy | NISE is an autonomous R&D Institute in the field of solar energy and undertakes activities related to research and development, testing, and certification of other associated technologies. |

| 3 | NIWE | National Institute of Wind Energy | The National Institute of Wind Energy is under the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy for the development of wind power in the country. It offers services in the wind energy sector in R&D, wind resource assessment (onshore and offshore), development of standards, testing, certification, and skill development. |

| 4 | IREDA | Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency | IREDA is a public limited government company established as a non-banking financial institution in 1987 to support the promotion, development, and extension of financial assistance for setting up projects relating to new and renewable sources of energy. |

| 5 | SECI | Solar Energy Corporation of India Limited | SECI is a not-for-profit company under the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. It was established in 2011 to help the solar energy sector. It is the only central public sector undertaking dedicated to the solar energy sector. SECI is the premier trader of renewable energy in the country. SECI Business area: Implementation of govt. scheme/tenders; Own projects; Project management consultancy; Power trading. It is the power procurement intermediary for projects being set up through its tenders, procuring power from developers and selling to DISCOMs though long-term PPAs/PSAs |

| 6 | SNA | State Nodal Agency | The State Nodal Agency for Energy Development (SNAED) is a body established by Indian state governments to encourage the growth of renewable energy sources and energy-saving technologies in each of its individual states. These organizations are in charge of putting into action various plans and programs for renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, biomass, and small hydropower. In order to hasten the adoption of renewable energy sources in their respective states, they also offer technical help, capacity building, and financial support to a variety of stakeholders, including project developers, customers, and government agencies. These organizations give approval for setting up the solar energy plants (tenders and commissioning of solar on ground, on rooftops, or floating. This agency varies by state; for example, Urja Vikas Nigam Limited, Bhopal (Madhya Pradesh), Uttar Pradesh New and Renewable Energy Development Agency, Haryana Renewable Energy Development Agency, and Rajasthan Renewable Energy Corporation Ltd. |

| 7 | ISTN | Inter-State Transmission Network | This network is used to convey electricity via the main transmission line from the territory of one state to another state, and the transmission of electricity within the territory of a state on a system that is built, owned, operated, maintained, or controlled by the CTU. |

| 8 | POSOCO | Power System Operation Corporation Limited | POSOCO is owned by the Government of India under the Ministry of Power. It was previously a subsidiary of the Power Grid Corporation of India Limited. It was formed in March 2009 to handle the power management functions of PGCIL. It is responsible for ensuring the integrated operation of the grid. It consists of five Regional Load Dispatch Centers and a National Load Dispatch Centre (NLDC) |

| 9 | RLDCs | Regional Load Dispatch Centers |

These are important links between generation and transmission that coordinate the power requirements of the consumers of electricity. There are five regional load dispatch centers across India: North regional load dispatch center; East regional load dispatch center; Northeast regional load dispatch center; West regional load dispatch center; South regional load dispatch center. |

| 10 | CEA | Central Electricity Authority | The Central Electricity Authority, established under Section 3 of the Electricity (Supply) Act, 1948, formulates plans for the development of electricity systems. It gives approvals as per CEA Regulation 2010. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dubey, B.; Agrawal, S.; Sharma, A.K. India’s Renewable Energy Portfolio: An Investigation of the Untapped Potential of RE, Policies, and Incentives Favoring Energy Security in the Country. Energies 2023, 16, 5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16145491

Dubey B, Agrawal S, Sharma AK. India’s Renewable Energy Portfolio: An Investigation of the Untapped Potential of RE, Policies, and Incentives Favoring Energy Security in the Country. Energies. 2023; 16(14):5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16145491

Chicago/Turabian StyleDubey, Bharat, Seema Agrawal, and Ashok Kumar Sharma. 2023. "India’s Renewable Energy Portfolio: An Investigation of the Untapped Potential of RE, Policies, and Incentives Favoring Energy Security in the Country" Energies 16, no. 14: 5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16145491

APA StyleDubey, B., Agrawal, S., & Sharma, A. K. (2023). India’s Renewable Energy Portfolio: An Investigation of the Untapped Potential of RE, Policies, and Incentives Favoring Energy Security in the Country. Energies, 16(14), 5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16145491